Cultural-Historical Psychology

2021. Vol. 17, no. 3, 125–134

doi:10.17759/chp.2021170316

ISSN: 1816-5435 / 2224-8935 (online)

Preparing Educators for Inclusive Bilingual Education: A Boundary Crossing Laboratory Between Professional Groups

Abstract

General Information

Keywords: boundary crossing, inclusive bilingual education, teacher education, higher education

Journal rubric: Problems of Cultural-Historical and Activity Psychology

Article type: scientific article

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17759/chp.2021170316

Funding. The reported study was funded by a Faculty Development Grant at Southern Connecticut State University under the direction of Angela López-Velásquez and Michael Alfano, 2013.

For citation: Martínez-Álvarez P., López-Velásquez A., Kajamaa A. Preparing Educators for Inclusive Bilingual Education: A Boundary Crossing Laboratory Between Professional Groups. Kul'turno-istoricheskaya psikhologiya = Cultural-Historical Psychology, 2021. Vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 125–134. DOI: 10.17759/chp.2021170316.

Full text

Introduction

Teaching and learning with children who experience the intersection of multiple layers of difference requires knowledge and services involving multiple areas in education such as bilingual education (BE), English as a second language (ESL) or teaching English to speakers of other languages (TESOL), and special education. While these areas are distinct in many ways, they are all impacted by deficit perspectives invading the education of bilingual children, and their disproportional representation in the high frequent disability categories [13].

This study consists of an exploration of pathways to prepare teachers to work more comprehensively with bilingual children, who are referred to as English language learners or ELLs. As a result of lack of inclusive designs but also a dearth of teacher preparation programs focusing on this intersection, bilingual children with disabilities are often forced to choose between their bilingual and their disability learning identities [11]. To address these issues, researchers explain, “a strong collaborative model in which professionals with expertise in different areas come together to solve a problem” is needed but still lacking [7, p. vi].

Reporting on the efforts of a group of university faculty to embark in boundary crossing across fields to prepare teachers for inclusive bilingual education, this study addresses two questions:

1) What boundaries surface discursively during interdisciplinary work involving higher education professors and where are these boundaries located in relation to the larger activity elements and levels at which the efforts are nested?

2) What kinds of epistemic learning actions for productive boundary crossing emerge in this context?

Theoretical Framework

This study draws from third-generation Cultural Historical Activity Theory [CHAT; 6], which is built on Vygotsky’s artifact-mediated learning [16]. Artifacts, as well as other elements such as division of labor, community, or the activity rules are all part of a person’s activity system. As people engage in collective activity, tensions surface and participants enact agency, creating new ways of engaging in collaborative activity, a process described as expansive learning [4]. Expansive learning is characterized by seven epistemic learning actions: (1) Questioning (criticizing or rejecting existing practices or knowledge); (2) Analyzing (exploring causes and explanations for its roots and development—historical-genetic; or for its internal systematized relations—actual-empirical); (3) Modeling the new solution (a simplified model of a new idea offering a breakthrough to tensions); (4) Examining the model; (5) Implementing the model; (6) Reflecting on and evaluating the process; and (7) consolidating into a stable new way of engaging in practice [5, pp. 383—384]. These actions are often used in cycles of collaborative work where there is a shared object to make learning apparent [7]. For this study, the evolving object was to prepare teachers to address the needs of bilingual children with and without disabilities.

Defining Boundaries

Boundaries refer to discontinuities and separation between the inside and outside of a community [14]. According to CHAT, boundaries are potential sources for learning as participants who work together toward a shared object engage in boundary crossing efforts [4].

The transfer of knowledge across boundaries is complex and requires developing common meanings and transformation of knowledge [14]. That is, knowledge sharing involves collective creative actions leading to “incremental change and the improvement of future outcomes of activities” [10, p. 117]. In this experience, we use the concept of boundaries as those temporal and spatial emerging locations of change, which can trigger learning and development [9].

Studying Boundary Crossing

Studies looking at the process through which boundaries appear showed that participants might indirectly express boundaries through discursive means [8;9]. Expressions can act as landmarks of boundaries in collaborative work across systems [8]. It is important to also connect the discursive landmarks of boundary expressions to the larger activity through its elements to establish the connection [8].

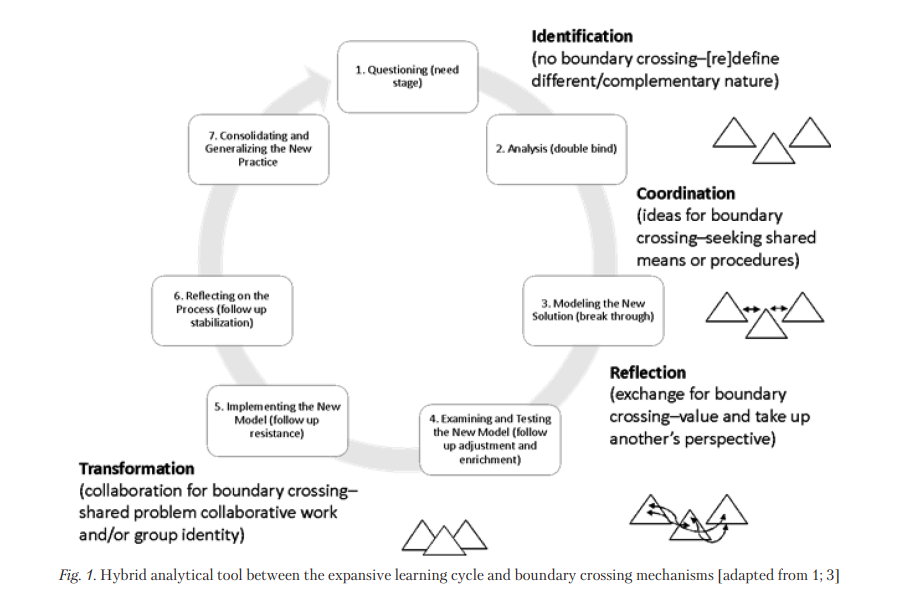

Boundary crossing has been studied along four learning mechanisms [1;2]: (1) Identification: (Re)defining the way in which the intersecting practices are different from one another; (2) Coordination: Means and procedures sought to assist in different elements working together; (3) Reflection: Mutually describing the involved practices and willingness to employ others’ perspectives; And (4) transformation: Change materializes in the existing practices. These different mechanisms could be studied together with three levels of interaction: The institutional level (crossing actions originated in from multiple organizations), the interpersonal level (crossing actions between groups across systems), and the intrapersonal level (crossing actions initiated by people in intersecting practices) [1, pp. 247—248].

Expansive Learning and Mechanisms

of Boundary Crossing

When the collaborative effort in expansive learning aims to promote boundary crossing, then arising tensions center on surfacing the boundaries and taking action to cross them, creating new ways of working together. The epistemic actions that describe learning during expansive learning cycles [5] can hence be connected to those used in defining boundary crossing learning mechanisms [1], generating a hybrid analytical tool.

As illustrated in fig. 1, the epistemic actions of questioning and analysis match the mechanism of identification in boundary crossing as here the boundary is identified and merely [re]defined. The learning action of modeling connects with the mechanisms of coordination and reflection where others’ perspectives are considered, and bidirectional boundary crossing is facilitated. Lastly, the learning action of examining and testing correspond to the mechanism of transformation as new in-between practices are designed.

Methods

This study is rooted in the “boundary crossing change laboratory” [CL; 8;9]. Boundary crossing CL focuses “on

developing collaboration and communication between two interlinked activities that are serving the same clients or realize parts of a broader object” [15, p. 190]. In a sense, the participants engage in collaborative work co-constructing their shared object through boundary crossing. Learning in this boundary crossing CL occurs through the collaboration at the junction of different activity systems when meaning making and transformation of practices take place and participants address and cross existing boundaries [1;4]. Researchers facilitate CL sessions through initial ethnographic work used as mirror material [16] to surface boundaries and promote the participants’ learning.

Participants and Context

The study took place in a university located in the Northeast of the U.S. Angela, a faculty member at this university, taught courses addressing bilingual education in the department of special education and reading. Angela invited Patricia, who works in a different university, to facilitate the CL experience with her, and collected the initial ethnographic data. After implementing the first three sessions together, Angela continued the process for three additional one-hour meetings.

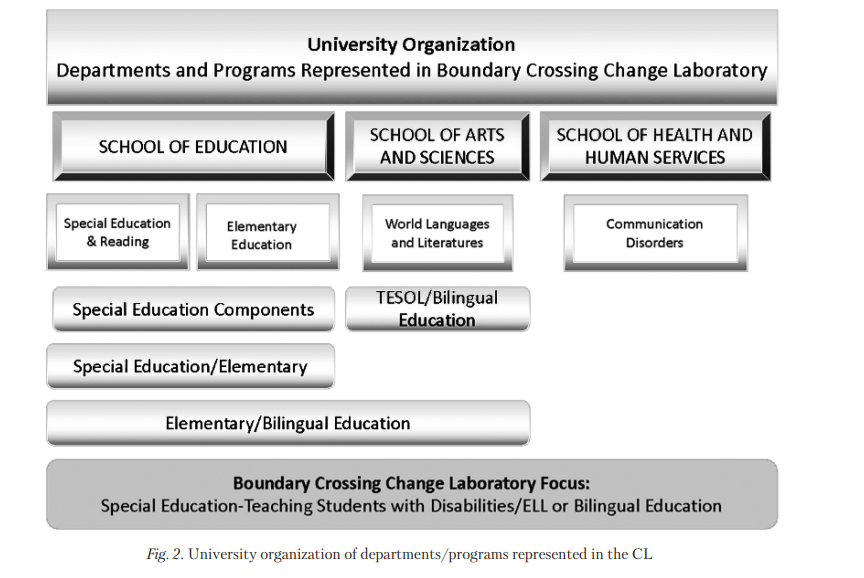

Fourteen professors representing different relevant fields participated in this research experience and two state representatives joined the CL on Day 3. Fig. 2 shows the university departments/programs and tab. shows participants’ pseudonyms, and their departments or positions.

Positionality

Angela was born and raised in Colombia and Patricia in Spain, and both moved to the US as young adults and learned English as a second language. Anu was born and raised in Finland, speaks Finnish, and learned English in school. Patricia and Anu identify as White, Angela as Latina, and the three identify as non-disabled cisgender females. Currently, Angela and Patricia’s research revolve mostly around inclusive bilingual/bicultural education. Anu focuses her research on organizational studies and has extensive experience with change laboratory methodologies. We found our experiences helpful in interpreting this work, but also collaborated to monitor our understandings.

Data Sources

Angela collected existing ethnographic data (i.e., 83 minutes of video-taped interviews with five faculty members; documents from the State Department of Education, demographics about bilingual learners; and university program descriptions).

On Day 1 and after participants’ introductions, Angela and Patricia showed parts of the video as mirror material to stimulate conversations. Consequently, they also prepared and presented theoretical and practical tools to assist the participants in analyzing existing boundaries and engaging in boundary crossing. Data in the form of discussions and conversations from the first three CL sessions (two hours each) were videotaped and transcribed.

Data Analysis

To analyze the data, we first identified discourse markers (landmarks) manifesting boundary expressions and participants’ indirect ways of expressing boundaries [8]. We created a chart with these landmarks and analyzed connections to the larger activity system elements [6]. We coded the data with three identified forms of boundaries elicited from the boundary expressions: Bilingual teacher preparation, cross-disciplinary programmatic, and paradigmatic. We then connected these to three levels of boundary expressions [1]: Institutional, interpersonal, and intrapersonal.

Participants’ departments or positions

|

Participant |

Department or Position |

|

Robert |

Department of Communication Disorders |

|

Elise |

TESOL Graduate Program |

|

Lorna |

TESOL Graduate Program |

|

Harriet |

Department of Elementary Education |

|

Lorena |

Department of Special Education and Reading |

|

Rachel |

Department of Special Education and Reading |

|

Leslie |

Department of Special Education and Reading |

|

Ruby |

Department of Special Education and Reading |

|

Diana |

Interim Dean |

|

Berta |

Department of Special Education and Reading |

|

Ben |

High School Teacher — Chair of English Learner Department |

|

Ryan |

Department of Special Education and Reading |

|

Gilda |

State Department of Education = |

|

Marta |

State Department of Education |

|

Angela |

Department of Special Education and Reading |

|

Patricia |

Bilingual/Bicultural Education |

We used the three codes of boundary expressions to categorize the excerpts that addressed these different boundaries and created “word clouds” (using Word Cloud free software) to pinpoint the main boundary topics.

We then used Engestrom’s [5] expansive learning cycle of epistemic actions, which were contextualized in Ak- kerman and Bakker’s [2] learning mechanisms as shown in fig. 1 to define the boundary crossing own epistemic actions. The researchers analyzed the entire data together following a “collaborative approach” [12, p. 398].

Findings

Multileveled Boundary Crossing Efforts

and Activity Elements

While the term boundary was not used directly by the participants, they used several terms and sentences indicating landmarks of boundary expressions. The analysis of these landmarks suggested three main forms of boundaries that needed to be explored and crossed. First, there were landmarks indicating “bilingual teacher preparation boundaries”, which the participants discussed in relation to candidates’ possibilities -or lack thereof- to obtain teaching certifications for inclusive bilingual education, certification requirements, and other aspects connected to boundaries between institutions. Second, there were landmarks pointing to “cross-disciplinary programmatic boundaries”, through which the participants discussed the need to work across disciplinary organizational units within the institution. The last group of landmarks referred to “paradigmatic boundaries” in relation to bilingual and inclusive education in society, education, and the world.

Landmarks of Inclusive Bilingual Teacher

Preparation Boundary Expressions

The term “cross” (or “crossing”) was used on six occasions by participants to point out boundaries in inclusive bilingual education: Five of the instances addressed bilingual teacher preparation boundaries, while one addressed cross-disciplinary programmatic boundaries. For example, Lorna used the term “cross-endorsed” three times in one turn on Day 1 to indicate how inclusive bilingual education certifications could be obtained (boundary expressions appear in cursive),

Lorna: We now have the option of students at the elementary ed[ucation] level doing the special ed[ucation] and the elementary ed[ucation] dual program, and then coming back and doing the master’s then to get cross-endorsed in ESL and bilingual ed[ucation]. One would get cross-endorsed in bilingual elementary, but you would not get cross-endorsed in bilingual special ed[ucation] because it doesn’t exist in the state [Day 1, Lorna]

Here, Lorna furthered a boundary situated beyond the educational institution. In this case, the boundary is with the State Department of Education, who sets the rules for certification and decides what certifications can be “crossendorsed”, or added to other certifications. In this way, these rules posed a boundary, which Lorna realized could not be crossed by the participants themselves (i.e., intrapersonal level) or by altering the rules within the university. Rather, it required faculty to work together (i.e., interpersonal level) to involve representatives from the state.

On Day 2, Berta questioned the issue of cross-endorsement that pointed to a boundary between the institution and the State Department of Education, and tried to explain it with these words,

Berta: [W]hy the special ed[ucation] person couldn’t get cross-endorsed or add a certification on the bilin- gual...presumably it must be because they don’t have a content area major...the bilingual certification requires content area knowledge as well [Day 2, Berta]

Berta explained the rules around what initial certifications can accept a cross-endorsement in bilingual education. The issue at the center was the need to have a major in a content area. Since teacher candidates in a program leading to teaching students with disabilities (discursively expressed here as special education) did not include a major in a content area, there was no pathway for cross-endorsement with the bilingual extension. These rules created a tension for the participants because they put an obstacle in their efforts to prepare teachers to address the needs of bilingual children with and without disabilities simultaneously.

In addition, the term “limiting” was used once to express boundaries in relation to bilingual teacher preparation. This term was introduced on Day 3 by Gilda, one of the representatives from the State Department of Education,

Gilda: [T]o be certified as a bilingual teacher you must demonstrate proficiency in whatever the underlying nonEnglish language is. If I’m a bilingual teacher and I have students in my elementary school that speak [a number of languages.] and I’m only proficient in one language... So, there is a built-in issue already that adds to the political culmination of what’s happening in the field...Special ed[ucation] is no different. The problem is that right now the certification is a comprehensive special ed[ucation] certification. non-categorical. So.I could be hired to teach any special ed[ucation] population. If you start categorizing and breaking down certifications into various discrete areas of training, you start limiting your pipeline [Gilda, Day 3]

This statement reflected how the representative analyzed the main specializations for teaching bilingual children with disabilities (i.e., bilingual and special education) as being “discrete” areas of training. She first raised the problem of having to be proficient in the language to teach bilingually (i.e., “to be certified as a bilingual teacher”), but later, she situated the issue in English as a second language, where children might be from different linguistic backgrounds. This contrasts with bilingual education where all children are learning the same two languages. While noticing the political layer embedded in the resistance toward bilingual education (i.e., “the political culmination of what’s happening in the field”), Gilda connected what she felt was, “a built-in issue” with the special education certification, where teachers are prepared to address the needs of a wide range of children with disabilities, even though these can vary greatly. She described this certification as being non- categorical at this moment, which she perceived as comparable to the bilingual extension certification because of the different languages that could be needed.

This excerpt hence was related to the outcome of the larger activity (i.e., to prepare teachers for working with bilingual children with and without disabilities). The representative also connected to the rules that govern bilingual education in the state. Aspects of certification can be interpreted as involving boundary crossing that goes beyond the educational institutional level to engage the State Department of Education, but it is also infused with the intrapersonal boundary crossing decisions prospective candidates would have to make.

Landmarks of Cross-Disciplinary

Programmatic Boundary Expressions

One instance where “crossing” was used as an expression of cross-disciplinary programmatic boundaries took place on Day 2. Angela engaged in the following discussion about expansion of, what she referred to as “our local expertise”, that could expand the opportunities of teacher candidates. She raised the possibility of boundary crossing as follows,

Angela: Expansion of what we have, using what we have, our local expertise to expand the opportunities for teacher candidates

Berta: [B]ut also provide more in-depth learning for our teacher candidates

Angela: And even for us, it would be acquiring expertise crossing our areas, some of us would be learning about special ed[ucation], some of us will be learning about bilingual ed[ucation] and TESOL, and others will be learning about disorders

Harriet: All of us, we have this underlying social justice theme [at the university] ... To me that’s what binds us all together. It’s our commitment to the kids in the classroom, and each of us have seen [kids] who desperately need well-trained special ed[ucation] teachers who are also well trained in bilingual ed[ucation]...We come with our different agendas, we come with our different focuses, but.we do that dance...we’re walking down the same path together

During this exchange, Angela used the term “crossing” to indicate the boundaries between the different areas, or fields of study. She highlighted how each field has a different “expertise” and how crossing areas of expertise would be needed to prepare teachers for the inclusive bilingual education classroom. She named the fields of bilingual education, TESOL, and language disorders, which were represented by the CL participants. The different fields have hence different artifacts and there is a need to share these mostly at the interpersonal level. As Angela highlighted the boundaries between fields, Harriet then reinforced the need to cross these boundaries. She expressed how all the participants shared an “underlying social justice” commitment, and that while they all had “different agendas” and “focuses”, they realize that working together and crossing those boundaries was needed to serve “the kids in the classroom”. In this way, Harriet acknowledged the agency of the participants in joining this boundary crossing CL, and the shared object that brought them together. Harriet used the metaphors “we do that dance” and “we’re walking down the same path together”, both of which expressed the shared object and commitment to cross boundaries for the sake of education (“that’s why we are working together”).

The term “barrier/s” was also used to directly refer to cross-disciplinary programmatic boundaries. In one instance when the term was used (Day 2), Patricia asked participants, while showing the activity system triangular model, about the rules that had come up and these were some responses,

Angela: The university, you know, restrictions with credits and do you want the undergraduate program or the master’s program.?

Lorena: The cost of the students and the requirements

Patricia: And Robert yesterday mentioned also his lack of faith in this process just because of the difficulty working with interdisciplinary departments

Robert: The institutional barriers

This exchange started out discussing teacher certification boundaries. It then shifted onto cross-disciplinary programmatic boundaries as Robert, a professor of communication disorders, used the word “barriers” in plural to summarize aspects of the organization within the institution as establishing a boundary between what could be allowed, or not, in relation to engaging in interdisciplinary work across departments. This aspect, connected to the activity’s rules, highlighted how the boundary could not be easily addressed out of intrapersonal (i.e., personal choice and perceived opportunities), or even interpersonal efforts (i.e., sharing of artifacts across programs) but rather it was an institutional level boundary (i.e., university cost and requirements) to their efforts.

Landmarks of Paradigmatic Boundary

Expressions

The term “barrier” was also used to express a paradigmatic boundary on Day 3, when Leslie, a professor of special education, explained,

Leslie: So, bilingualism is highly valued and I think here we’ve got this kind of politics where people are really schizophrenic about the whole dual language issue, and that’s a real barrier [Day 3, Leslie]

With these words, Leslie pointed out how the sociopolitical context in the U.S. in relation to bilingual education placed what she described as “a real barrier” to expanding possibilities for inclusive bilingual education teacher preparation. We interpreted this as an expression of a paradigmatic boundary at the sociopolitical level. This barrier engaged aspects of rules that limit high quality bilingual education program growth, and the object or motif of the participants for being in the activity.

Boundary expressions manifested paradigmatic boundaries in relation to differences between approaches within areas such as TESOL and bilingual education. For instance,

Patricia: And another discussion is the difference between TESOL and bilingual because they are [.situated as] two separate fields

Elise: [T]hey are kind of separate here.Unless you are bilingual and you have training in a subject area, in math for example, you can’t get certified in bilingual

Patricia: So, you made a very good point. In order to. have a bilingual certification, one of the requirements that all the programs have is to fluently speak the

other language, because you have to be ready to teach content in both languages

Here Patricia and Elise discussed differences between the fields of TESOL and bilingual education (i.e., the need to be fluently bilingual).

In a separate expression of boundaries, the need to cross between teacher preparation programs and actual practice in the classroom was highlighted. For example, one of the state representatives explained,

Gilda: So, we’ve got to address that, we’ve got to seek input from the field and I think once you do, you are going to hear very clearly that they want training that really addresses what they are facing in the classroom... The debate at the reform level in education right now is if it does not add value to teacher’s skills, more importantly, it doesn’t add value to their content knowledge and content pedagogy because there is no research-based connection.I actually want to say.communication disorders is missing from there and it really needs to be an integrated part of these programs [Day 3, Gilda]

This excerpt raised the issue of the lack of communication (i.e., boundary) between practice and theory and the need for university teaching to be highly practical. In a sense, this was a call for sharing artifacts across institutional spaces (i.e., institutional level). Furthermore, Gilda highlighted that there was a need for programs such as “communication disorders” to also be “an integrated part” of the different teacher preparation programs. This is important but fields connected to disabilities, such as communication disorders, have historically kept separate from bilingual education.

Epistemic Learning Actions

for Boundary Crossing

This section addresses the second research question: What kinds of epistemic learning actions for productive boundary crossing emerge in this context? This part is based on the hybrid analytical approach illustrated in fig. 1. Given its importance, the epistemic actions and boundary crossing mechanisms hybrid is used to explain the learning during boundary crossing efforts in reference to the first type of boundaries that surfaced discursively (bilingual teacher preparation).

Learning in Relation to Bilingual Teacher

Preparation Boundaries

The word-based analysis revealed that the most frequent terms of all excerpts that were coded as addressing bilingual teacher preparation boundaries manifested areas of participants’ interests that prompted expansive learning. The word frequency visualization is shown in fig. 3.

The visualization exposed five terms that appeared more than 20 times in these excerpts: “Special education” (35 times), “State” (30 times), “teachers” (30 times), “certification” (28 times), and “students” (21 times). Hence, the themes that manifested through this visualization focused on certification requirements at the State level while aiming to attend to teachers’ and students’ needs.

There were two main epistemic actions from fig. 1 that referred to teacher preparation during the CL. These were analyzing, which involves identification and (re)defining of intersecting practices, and modeling, which involves coordination (seeking means and procedures for diverse practices to cooperate efficiently in distributed work) or reflection (engaging in perspective making and taking). The analysis showed how the progressively deeper exploration of aspects of the boundary redirected the shared object from aiming for a new program possibly leading to multiple teaching certifications, to a practical approach where the intended outcome was teacher candidates learning about, and serving, bilingual children. The learning trajectory that took place during the meetings in the context of teacher preparation boundary crossing manifested through the participants’ actions. Several volitional actions, which are illustrated next, aimed at modeling a solution to the issue through coordination and reflection.

On Day 1, participants primarily engaged in analyzing the programs they had where teacher candidates could already cross boundaries. The participants learned from one another that they already had an undergraduate program that allowed them to obtain a degree, along with elementary special education certifications (i.e., the “collaborative” program). However, adding the bilingual certification to that program was situated as a complex issue (i.e., undergraduates might not have enough time to take all the courses).

Angela followed up on this conversation explaining what one of the State representatives had said during an initial conversation with her. As she spoke, the analysis and beginning of modeling took place as a form of an epistemic action on the part of the professor from the reading program,

Angela: I talked to Gilda on the phone.and her main concern is the literacy part, it’s reading. She said [that] at the undergraduate level, [it was] impossible for a teacher candidate.to have the three certifications, the special ed[ucation], the elementary ed[ucation] and the

f

Rachel: And graduate with the bachelor’s, you know? If we could make the program such [.] that they graduate with both the bachelor’s and the master’s, I.think that would be better because they would be taking so many courses

In this excerpt, Rachel enacted the epistemic action of “modeling” in response to the State representative’s concerns expressed to Angela prior to the CL, by presenting a possible way to address the issue of the many courses the candidates would need to graduate with three certifications (analysis-identification): A joined collaboration for a bachelor’s and master’s degree program.

On Day 2, similar boundary-related aspects around certification were brought back. The participants took additional volitional actions pointing to the need to cross the boundary between the university, the schools, and the Department of Education to find out if there indeed was a need for bilingual teachers with expertise on teaching students with disabilities,

Ruby: [A]re administrators [in schools] looking for this?

Elise: That’s the question, exactly. Do we want to have teachers who are separately certified in bilingual and special education, or do we want to have a merged certificat[ion program]? And, if we want to have a merged certificat[ion], then it totally makes sense to have this interdisciplinary program

Here, Ruby and Elise used “identification” as they suggested the need to cross and (re)define the boundary separating university and school personnel. The epistemic action of identification helped the participants think about what could be more beneficial: A merged certification program at the undergraduate or graduate levels, or both. This was an important shift that changed the direction of the activity. Initially, the group was focused on enacting across-fields boundary crossing merely through the addition of certifications or taking courses separately and obtaining approval from the State.

As the conversation continued, more ideas were generated. For instance, Ruby, the Chair of the Special Education and Reading Department, indicated that maybe a graduate program (master’s degree) made most sense,

Ruby: I’m just seeing it at the master’s level because, just like kids needing the foundation, a learner bridge, teachers need to have a foundation in teaching, and I think they get that in their pre-service programs, that’s why I think this is a higher level [Ruby, Day 2].

With these words, Ruby situated learning to teach as a process that takes years and that might even require longer than the duration of an undergraduate program.

Furthermore, Robert, from the Communication Disorders Department, also, in a modeling effort, explained that instead of creating a program leading to a teaching certification, they could create a program that grants a “certificate”. A certificategranting program focuses on providing pedagogical knowledge but is less regulated by the Department of Education.

At this point, Ruth during Day 2, went back to the idea of a master’s degree and raised the possibility to obtain funds through a grant, “[for] the master’s type of program. there might be grant money available”. With this proposal, she engaged as part of the collective work in constructing a possible model of the new idea, which had been entertained earlier in the CL, but adding the need to obtain grant support. This contribution added a level of analysis (epistemic action) and through reflection (epistemic action of identification), participants tried to convince others about how efficient a certificate program could be to work with people in school districts (crossing boundaries).

While participants generated multiple programmatic ideas on Day 2, the group kept going back to the need to really find out from schools and administrators about what they needed. Ideas to do this included Ruby’s suggestion to “get some data from the State”, and Robert’s idea to “send out a survey” to school administrators. Both agreed on the survey being “what we need to pitch it to the next level” [Ruth, Day 2]. These different actions pointed to efforts to cooperate within and outside the university effectively, rather than just creating a program which might not meet the needs in schools.

While the faculty generated several options to cross boundaries, the issue of rules continued to be present. Since the State collected data on schools and set the rules for certification, the representatives were perceived as an important partner with whom they needed to cross boundaries. The faculty questioned having to follow their rules,

Ruby: [W]e can’t sit back and keep waiting for the state to decide what they are going to make in terms of certification rules. We are supposed to be the thinkers!

Harriet: I would like to present to the state that there’s a body of people down here doing really excellent work.Yes, we want your input, but we also have things to tell you that we do well

With these words, the participants expressed the need to take action to change things to accomplish their object (i.e., better preparing teacher candidates for inclusive bilingual education). The statement “we want your input, but we also have things to tell you that we do well”, showed their identification of a boundary along with the need to cross it and work together.

The ideas generated on Day 2 were reanalyzed as the state representatives joined the group on Day 3. Boundaries was reestablished, but also renegotiated as they together explored possibilities. The efforts described within the teacher preparation boundaries, can be recognized as a form of learning where multiple perspectives and new ideas were developed.

Discussion and Implications

The data showed that three main boundaries were discussed during the initial three sessions of this CL in inclusive bilingual education (i.e., bilingual teacher preparation, cross-disciplinary programmatic aspects, and paradigmatic related boundaries). These boundaries surfaced while discussing the rules and artifacts of the shared activity of the participants.

In terms of the levels, while boundary crossing at the intrapersonal level, and at the interpersonal level were important, the need to engage multiple institutions (i.e., schools and university) was centered. In addition, the discussion manifested that there was a need to go beyond the institutional level to reach to policy makers and address the sociopolitical resistance against bilingual education.

The second research question investigated the kinds of epistemic learning actions for boundary crossing that emerged. In the context of bilingual teacher preparation boundaries, the participants engaged primarily in analyzing their existing comprehensive programs. However, they also embraced modeling new options. Through volitional actions, the participants realized that their object was to engage in inter-disciplinary work, but they could not do that unless they created a “merged” program. Research supports this need to create merged programs where courses and clinical experiences in classrooms focus on the intersection of bilingualism and disabilities, rather than providing candidates with separate experiences [11].

These findings have implications for the preparation of teachers for inclusive bilingual education as these boundaries will be present in similar efforts at the university levels in states across the U.S. The boundary locations point to the importance of attending to the sharing of artifacts across fields, the importance to attend to how rules can limit university creative actions, and the need to attend to boundaries at the policy and sociopolitical levels.

In terms of epistemic learning actions, the study’s findings show how there was important progress as participants considered options that required the least amount of time and no additional cost (i.e., sharing existing expertise within the university). This study’s findings suggests that well planned collaborative experiences can assist in mediating learning and transformation.

References

- Akkerman S., Bruining, T. Multi-level boundary crossing in a professional development school partnership. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 2016. Vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 240— 284. DOI: 10.1080/10508406.2016.1147448

- Akkerman S.F., Bakker A. Boundary crossing and boundary objects. Review of Educational Research, 2011. Vol. 81, no. 2, pp. 132—169. DOI: 10.3102/0034654311404435

- Engeström Y. Chapter 7: Activity theory and learning at work. In Malloch M. et al. (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Workplace Learning. London, U.K: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2010, pp. 74—89. DOI:10.4135/9781446200940.n7

- Engeström Y. Expansive learning at work: toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 2001. Vol. 14, pp. 133—156. DOI:10.1080/13639 08002 00287 47.

- Engeström Y. Innovative learning in work teams: Analyzing cycles of knowledge creation in practice. In Engeström Y., Miettinen R., Punamäki R-L. (eds.), Perspectives on Activity Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, pp. 377—404. DOI:10.1017/cbo9780511812774.025

- Engeström Y. Learning by expanding: An activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Helsinki, Finland: Orienta-Konsultit, 1987. 269 p.

- Hamayan E. et al. Special education considerations for English language learners: Delivering a continuum of services (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Caslon Publishing, 2013. 304 p.

- Kerosuo, H. Examining boundaries in health care — Outline of a method for studying organizational boundaries in interaction. Outlines. Critical Social Studies, 2004. Vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 35—60.

- Kerosuo H. Boundaries in health care discussions: An activity theoretical approach to the analysis of boundaries. In Paulsen N., Hernes T. (eds.), Managing boundaries in organizations: Multiple perspectives. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, pp. 169—187). DOI:10.1057/9780230512559_10

- Ludvigsen S., Nerland M. Knowledge sharing in professions: Working creatively with standards in local settings. In Sannino A., Ellis V. (eds.), Learning and collective creativity: Activity-Theoretical and sociocultural studies. London, U.K: Routledge, 2013, pp. 116—131. DOI:10.4324/9780203077351-14

- Martínez-Álvarez P., Chiang H.M. A bilingual special education teacher preparation program in New York City: Case studies of teacher candidates’ student teaching experiences. Equity & Excellence in Education, 2020. Vol. 53, no. 1—2, pp. 196—215. DOI:10.1080/10665684.2020.1749186

- Smagorinsky P. The method section as conceptual epicenter in constructing social science research reports. Written Communication, 2008. Vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 389—411. DOI: 10.1177/0741088308317815

- U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, Office of Special Education Programs. 37th Annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2015. Washington, D.C., 2015. 284 p. DOI:10.1002/9780470373699.speced1499

- Wenger E. Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. 318 p.

- Virkkunen J., Newnham D.S. The Change Laboratory: A tool for collaborative development of work and education. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Sense Publishers, 2013. 294 p.

- Vygotsky L.S. Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978. 174 p.

Information About the Authors

Metrics

Views

Total: 414

Previous month: 15

Current month: 5

Downloads

Total: 209

Previous month: 6

Current month: 2