Cultural-Historical Psychology

2022. Vol. 18, no. 1, 90–104

doi:10.17759/chp.2022180109

ISSN: 1816-5435 / 2224-8935 (online)

Generations Attitudes from the Point of View of a Modern Primary School Age Child

Abstract

The work is aimed at studying the current attitude towards the ageing person by the generation of “digital childhood” in comparison with the expectations of representatives of the late-age generation. We assumed that, against the background of modern transformations of intergenerational traditions, we can expect descendants to recognize the preservation of the standard of ancestral behavior. 284 residents of Petropavlovsk- Kamchatsky were surveyed: 40 respondents from 57 to 80 years old and 122 child-parent dyads (children from 8,2 to 9.6 years old, parents from 27 to 61 years old). At the first stage, data were obtained from parents using the author's questionnaire allowing them to present their opinion about the real state of the relationship between children and their grandparents and the importance of (non-)participation of grandparents in the upbringing of their grandchildren. At the second stage, the analysis of the interviews in the focus groups of schoolchildren and a gerontological sample concretized attitudes towards a person of senior age and allowed independent experts to identify relevant categories (based on content analysis). At the third stage, options for reflecting the (non-)consent of the older generation with children's judgments were investigated. The results were evaluated on the Likert scale. It is shown that, despite the significant choice of children's attitude as condescending compassion, in the range of consent of the expected attitude, children's variants of continuity of preserving the experience of obligatory and valuable behavior of the grandparents are presented. The data obtained emphasize the problem of recognizing the uniqueness of the experience of each generational group as a source of generational solidarity and the basis of cultural adaptation to age.

General Information

Keywords: younger schoolchildren, digital childhood, the late-age generation, to “regret” and “understand-respect”, the standard of ancestral behavior

Journal rubric: Developmental Psychology

Article type: scientific article

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17759/chp.2022180109

Funding. The research was carried out with the financial support of research projects by Kamchatka State University for the project number АААА—А19—119072290002—9.

Acknowledgements. The authors express their gratitude to the staff of the «Center for Personal Development and Psychological and Pedagogical Assistance to the Population» for their cooperation and creation of favorable conditions for the study.

Received: 14.05.2021

Accepted:

For citation: Glozman Z.M., Naumova A.A., Naumova V.A. Generations Attitudes from the Point of View of a Modern Primary School Age Child. Kul'turno-istoricheskaya psikhologiya = Cultural-Historical Psychology, 2022. Vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 90–104. DOI: 10.17759/chp.2022180109.

Full text

Respect for parents and elders is the basis of humanitarianism

Confucius

Be careful with children! One day they will rule the world!

A. Brilliant

Introduction

The peculiarities of relationship between ancestors and descendants have always been and remain one of the topical research problems of psychological science. It is known that human society exists and develops thanks to the interaction of generations. It is safe to say that human civilization has survived largely due to the possibility of passing on to new generations the experience accumulated by previous generations, thereby simultaneously ensuring the implementation of opportunities and traditions of the social community. The continuum of this construct is in demand both in the process of functioning of everyday life needs and in the reconstruction of the accumulated experience of the previous generation to support and build up a new layer of ways of interconnection with rising descendants. In different epochs, the nature of relationship between ancestors and descendants was determined by the specificity of society’s development.

Today the world is rapidly changing, representing the lives of contemporaries in a highly accelerated pace and radical socio-economic and cultural transformation of society (globalisation, digital informatisation, etc.).

The present reality also demonstrates qualitative changes in the demographic structure: increase in life expectancy, changes in the boundaries and ratios of age groups, emergence of new age stages — “digital childhood”, entering adulthood, increase in the stage of productive professional activity, as well as the emergence of productive post-professional life [1; 21; 23]. According to demographic data, today’s Russia is characterized by three or often four generations (children — parents — grandparents — great-grandparents). We agree with the researchers who suggest that modern intergenerational relations are a wide layer of interactions determined by the features of generational identity (perceptions, values, orientation, etc.) [22].

It is especially important in a situation when “humanity has to adapt forcibly to the new world which is transformed before our eyes from vertical to horizontal” where the normative model of a clear opposition between “digital childhood as a special historical type of childhood” [18, p. 71—72] and adulthood as a standard, “an image of its necessary future” [15, p. 5] is weakening. In addition, it is important to note that today information and computer technologies are able to act as an agent of child socialization, which, in fact, is a serious competition to the institutions of socialization [17; 18; 19].

It is a fact that an adult is no longer a unique bearer of culture, the intensity of the child’s communication with adults and with other children is decreasing, and the efficiency of traditional practices of care and education is becoming ambiguous.

These days there has also been a radical new “discovery” of gerontogenesis, the shift from an image of old age as a time of dependence and decline to the concept of active ageing, which is certainly a significant cultural change [3]. In the literature, we can more often find versions of the representation of ageing in the concept of “successful old age” and the “paradox” of modern old age: with increasing age subjective well-being can be maintained and/or even improved [12; 37; 38; 39].

However, it should be noted that against the background of the triumph of prosperous and productive old age that undoubtedly takes into account a special nature of long life, the issue of late age negative and rigid stereotypes influence, that, on the one hand, trigger the formation of destructive, dependency-passive behavioral constructs of the ageing person, and on the other hand, the discriminatory neglect of the older generation by the younger ones, still remains highly topical [7; 10; 35]. The presented realities significantly reduce the value basis of intergenerational relations, and contribute to an increase in the distance between the generational cohorts.

At the same time, a number of researches of the younger generation’s perceptions of ageing indicate that the images of ageing and old age that lay the foundation for their own ways of ageing and their likely attitudes towards the older generation are initially based on early personal experiences of interaction with their grandparents [21; 30; 40]. Stereotypes about the ageing process and older people in particular are internalized throughout life in two fundamental ways: top-down (from society to individuals) and over time (from childhood to old age) [34]. As people are getting older, stereotypes learned in childhood and adulthood tend to eventually turn into “self-stereotypes”, which often lead to negative consequences for older people [33].

We support the view of some researchers that intergenerational interaction and intergenerational solidarity plays an important role in the psychological well-being of both older people and the younger generation [24].

This brief overview makes it clear that it is important and essential to research the specificity of the relationship between ancestors and descendants in the context of contemporary reality.

This fact gives a reason to formulate the aims of the research:

— to analyse the potential experiences of (im)possible interactions between junior schoolchildren and older relatives;

— to explore, on the one hand, the current attitudes of younger school-age children towards the ageing person and, on the other hand, the expected attitudes of the older generation towards them.

Based on the approaches described, we hypothesize that despite the transformation of traditional forms of intergenerational interaction and rapid contemporary changes in the socio-cultural context of intergenerational life, we can expect the preservation of ancestral coping behaviour, which is valued by descendants as the most valuable and compulsory experience.

Research Organization and Methodology

The total sample of the research included 284 respondents: 122 child-parent couples and 40 participants aged between 57 and 80.

The child sample consisted of 122 primary school children aged between 8,2 and 9,6 years (52,5% of girls and 47,5% of boys).

The parental group (84,4% of mothers and 15,6% of fathers) consisted of respondents aged 27 to 61: (42,6% — aged 27—35 years; 53,4% — aged 36—61 years). 52,5 % of the respondents had higher education, 25,5% of the group had secondary professional education, and 31,9% had secondary education. 77,9% of parents informed that they had two-parent families.

Written consent was obtained from the parents for each underage respondent to participate voluntarily in the study. All of the schoolchildren surveyed did not have any serious illnesses, socialization difficulties or problems in cognitive development.

The sample of older respondents consisted of regular gerontological art group participants aged 57 to 80 years: 47,5% — aged 57—65 years; 45% — aged 66—75 years; and 7,5% — aged 76—80 years. Among them, 70% were females and 30% were males; 25% were married, 12,5% were divorced, and 62,5% were widows and widowers. Among the respondents, 22,5% had a higher education, and 77,5% had secondary and secondary professional education. A total of 47,5% did not work. 17,5% of the respondents lived together with children and/or grandchildren and provided much of the childcare, 57,5%lived separately but communicated and provided occasional help; 25%lived separately but had very limited communication and assistance in the upbringing of their heirs.

An ethical agreement was also signed by the adult participants to make the results of the study available to the professional community.

The research included several stages.

The first stage was conducted as part of the preparation for the “International Day for Older Persons”, we used the following methods:

— questionnaire survey of parents. The questionnaire included both standard questions about the socio-demographic characteristics of the participating parents and all grandparents representing the schoolchildren’s family, and a number of questions clarifying the extent to which parents used support from grandparents to care/raise their grandchildren; information about the children’s availability of communication / absence of communication with their grandparents; and questions aimed at collecting data on parents’ opinions about the importance of (non)participation of the older generation in raising their descendants. It was anticipated that the questionnaire data would provide information about the potential experiences of (im)possible interactions between the participating schoolchildren and older generation relatives.— focus group interviews were conducted with 10-12 participants in each of the child and gerontological samples. Data was collected from students at general education schools in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, and at the experimental site of the Vitus Bering State University Centre for Personal Development and Psychological and Pedagogical Assistance to the Population for the cohort of older participants.

The moderators were graduate students of the Faculty for Psychology and Pedagogy at Vitus Bering Kamchatka State University (n=26, aged 21—24). The interviewees were asked the following questions: “How, in your opinion, is it important/necessary/acceptable to treat the elderly and the old?”. They were asked to list the possible options. In the subsequent group discussion, answers to the clarifying questions were discussed (e.g. “Why do they think so?”, “How can they explain/describe their attitudes?”).

The research objective of the second stage was to ask independent experts to analyze the responses from the focus groups. Data processing was carried out with the use of conventional content analysis (summarizing the responses, identifying quantitative categories and compiling a relevant list of “attitudes towards an ageing person”) [15].The coding of categories was carried out by the authors together with the experts during the group discussion.

The role of experts was performed by extramural students of the Faculty for Psychology and Pedagogy of Vitus BeringKamchatka State University, receiving a second higher education (n = 25, aged 18 to 47).

At the third stage, older respondents (n=26, aged 65 to 72) were asked to express their (dis)agreement with the children’s judgments of dominant attitudes towards the ageing person. Responses were asked to be rated on a Likert scale ranging from -3 to +3, where 3 indicates strongly agree, 2 — rather agree, 1 — partly agree, 0 — it is difficult to say whether agree or disagree, -1 — partly disagree, -2 — rather disagree, -3 — strongly disagree. Judgments with a mean score of -3 to -1 were rated as reflecting disagreement, those with a score of +1 to +3 as agreeing and a score of < -0.99 to +0.99 were categorized as neutral. A mean score was calculated for each component.

Descriptive statistics, Fisher’s transformation test (φ) and Pearson’s chi-squared test (χ2) were used for statistical analysis of the data.

Results of the Research

Analysis of the socio-demographic characteristics of the elderly respondents shows that grandmothers (average age 58) with higher or specialized education are significantly more prevalent among the grandparents (Table 1).

There is a noteworthy fact of continued employment for most of the studied cohort with the status of a pensioner. It is important to note that the residents of the Kamchatka peninsula belong to the preferential categories of establishing retirement pension — 51 years and 6 months for women and 56 years and 6 months for men, respectively [14]. At the same time, an analysis of the literature captures evidence that it is the status of official pensioner that often acts as a trigger for “rapprochement” with the grandchildren. Some researchers present data showing that it is grandmothers under 65 years old who combine the opportunity and need to interact with their grandchildren up to the age of 10 or 12 years, which actually reinforces the above-mentioned reflections [4; 9].We believe that arguments about the existing need of an ageing person to receive both pension benefits and wages and/or the importance of maintaining employment in order to maintain quality of life, activity and autonomy independently, can be presented as an explanation of the above contradictions or, rather, as a trend towards them [2]. At the moment, quite often this situation is not an alternative one.

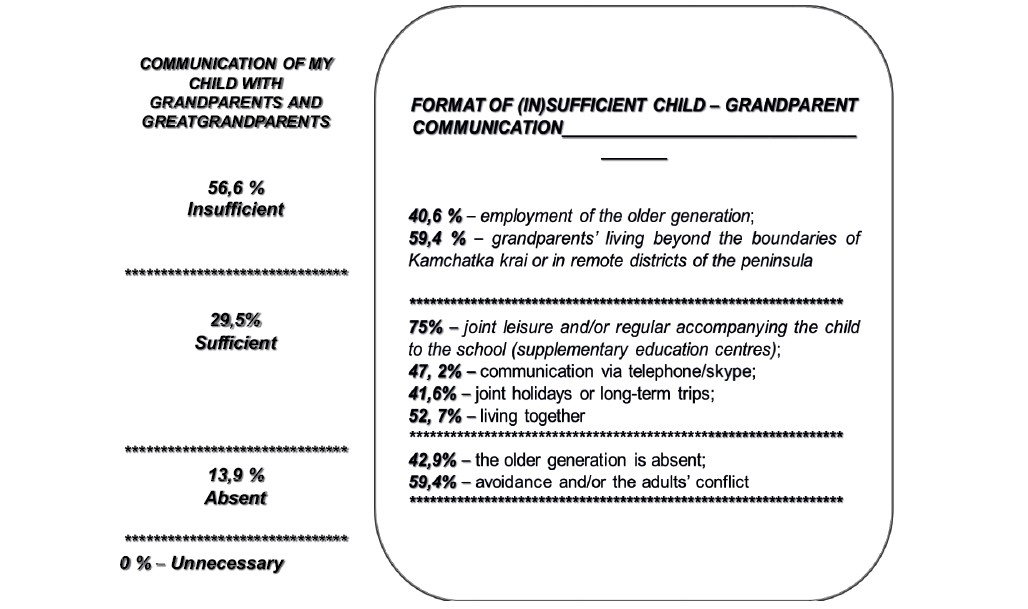

A significantly higher proportion of parents (p ≤0.05) identified the employment of the older generation, the living of grandparents in remote, inaccessible and often informationally isolated locations as a negative region-specific factor limiting communication with grandchildren (Figure 1).

Next, let us analyze other data from the parents’ questionnaire. We used the objective data from individual authors in the analysis of the parent questionnaire, confirming the fact that the features of “older and younger parents” interactions concerning matters of support and care for children depend largely on the type of household [26].

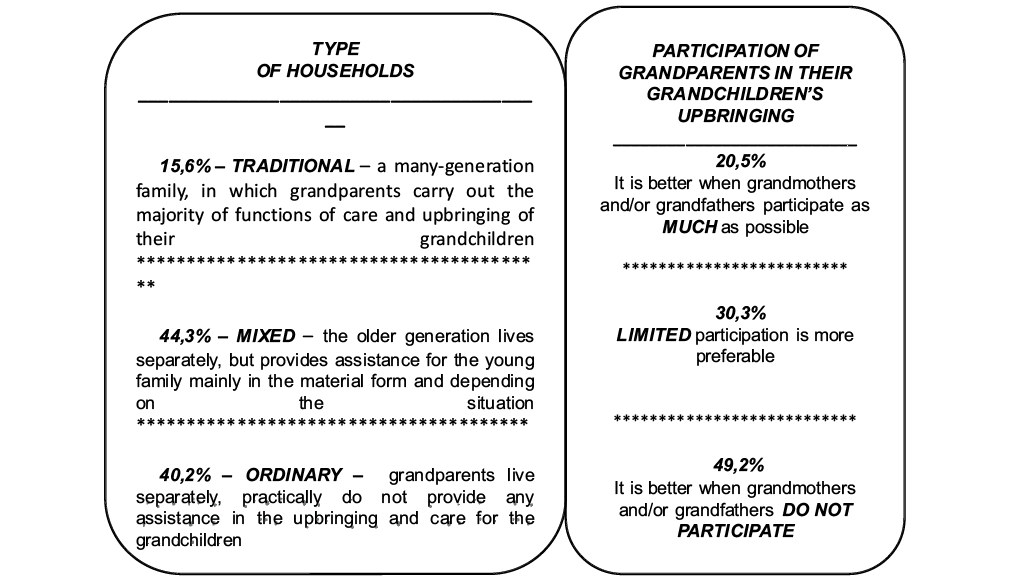

Our study showed that a higher percentage (p≤0.01) of parental choices indicated a trend towards low level of grandparents’ involvement in helping and accompanying their grandchildren during their childhood (Figure 2).

At the same time, parents show significantly more frequent choices (p≤0.05) of their responses confirming their beliefs that it is better for grandparents to have limited and/or no involvement in their grandchildren’s upbringing.

Thus, the information obtained from the questionnaire data indicates a certain deficit in the potential experience of (im)possible interaction between junior schoolchildren and relatives of the older generation. Unfortunately, our results coincide with the Russian demographic trends of recent years, which gives a reason to speculate about the weakening of intergenerational exchange [6]. Probably, this fact may also indicate the transformation of traditional forms of intergenerational interaction. As a supporting illustration of our data, we can refer to modern publicity, where the facts of increasing demonstration of modern Russian grandparents as “realities of the modern norm” of the role of the “visiting governor or governess” and sporadic recreational activity, combined with material support of grandchildren are increasingly discussed [26, р. 44].

Let us further analyze the results of the focus group interviews1 with children and older respondents.

On the basis of semantic similarity, the experts identified the categories of “attitudes towards the elderly and the old” from the total number of responses (162 younger schoolchildren and 128 older respondents) (Table 2).

A comparative analysis of category representation shows group specificity: respondents of primary school age voiced their attitude towards the older generation in the sequence “pity — respect” significantly more often (p≤0.01), and in the older age cohort it was “understand — respect”.

In addition, the categories “understand” and “honour” were found to be irrelevant in the children’s sample, and several pupils (their answers are categorized as “do not know”) were unable to describe their attitudes to the older person at all. The following arguments were presented as explanations by pupils: lack of personal experience of interaction with the older generation; not understanding (not accepting) the difference between older adults and “other adults”; unattractiveness, boredom and low value of the discussion.

The next step was to carry out a qualitative analysis of the dominant relational categories: for the group of primary school children it was the “pity” category (df= 150, p≤0,01) and in the sample of older generation — the categories “understand” (df=25, p≤0,01) and “to respect” (df=20, p≤0,01) based on specifying judgments.

Let us turn to specific examples of answers and the result of their analysis in the group of elementary schoolchildren. 244 explanatory judgments were presented by pupils for 115 choices of “pity”: 19,3% of participants gave one example each, 12,7% gave two answers, 10,7% of pupils recorded three options each, 3,3% gave four examples each, and 2% of respondents had five answers.

The experts structured all the answers by components and determined the level of their expression (Table 3).

So, the result of the content analysis of the descriptions of children’s attitude of “pity” towards an ageing person demonstrates its multi-value and multi-component character. However, statistical significance (df=66, p≤0,05) is determined only for the component that reflects the descriptive picture of external manifestations of low physical (bodily) competence and poor adaptability to life in old age, i.e., “physiological loss”.

Now let us turn to the answers explaining the semantic content of the two significantly dominant categories of attitude expected by the older generation — “understand” and “respect”. The result of the content analysis of specifying judgments in the indicated categories fixes their identity, which allowed the authors to combine them into the general category “understand — respect”, which represents the reflection of attitude on the whole as need for recognition of experience and merits, seeking compromise, ability to empathize and understand the emotional state of the older generation (Table 4).

It seems to us that it is also important to demonstrate examples of responses of the “honour” attitude category, reflecting the expectation of the older generation to have their descendants recognize the importance and respect the life they lived in terms of its heritage (“be my reflection at least a little bit”, “keep me in yourself”, “continue my creation of tatting”, “will even there, hopefully in heaven, be happy if they keep my cliff, gear and my ice-fishing ritual”)3.

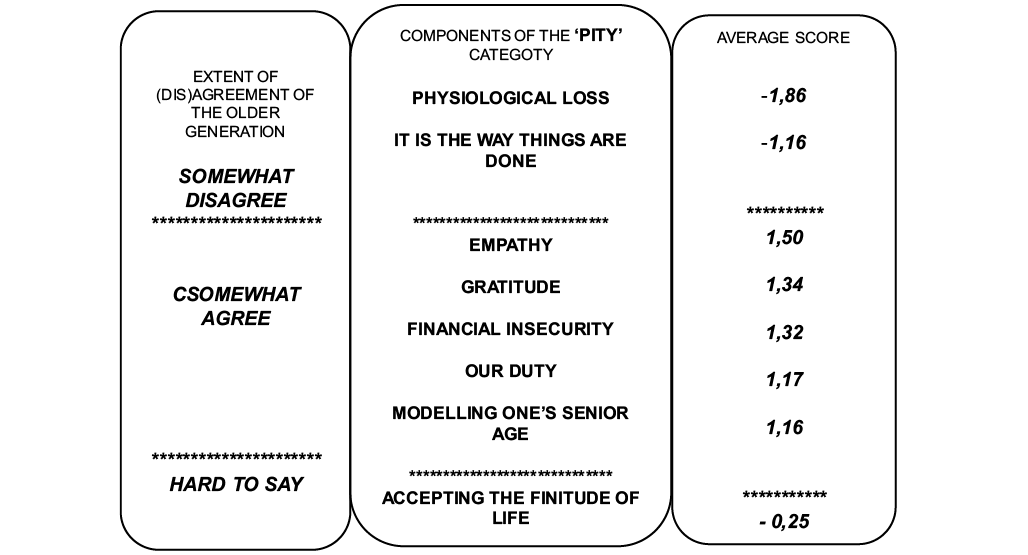

The next research task was to analyze the extent to which older respondents (dis)agree with the statements included in the components of the children’s attitude category “regret” (Figure 3).

Older respondents disagreed with children’s choice, more frequently with the components “physiological loss” and “it is the way things are done”. It is likely that for the adult sample this variant of attitude description is interpreted as a negative, rather stereotype-traditional attitude towards old age, dominated by a picture of rather disparaging and condescending compassion. The highest agreement score was given by the older participants to such attitude as the child’s ability to understand the condition of an ageing person (the “empathy” components) and readiness to express a sense of appreciation to him or her (“gratitude”).

Results of Discussion

In this research the authors have attempted to explore possible variants of current and expected attitudes towards an ageing person from the perspective of junior schoolchildren and adults who have reached the stage of gerontogenesis.

Our research has shown that, on the whole, the respondents in the children’s sample represent the picture of actual attitudes towards the elderly rather through the prism of the deficit of potential experience of interaction with their ancestors. A number of arguments can be cited to explain this.

A significant proportion (33,9%) of the grandparents of our sample are not in the range of old age (according to the WHO classification) and it is unlikely that they can fully demonstrate the image of ageing and old age in “their young ancestry”.

In addition, earlier in our other researches [12; 36] we recorded the data concerning the fact that in the recent decade the relationship between children and parents in many Kamchatka families had been increasingly optional, which is also reflected in the present study. Thus, more than half of parents indicated insufficient communication between their child and the older generation and 84,5% of “young” families confirmed the fact of existing situational support by their parents, mostly in the material form. Among the dominant factors specifying the deficit of live communication between ancestors and descendants, the respondents noted the objective and forced need to maintain employment of the older generation of retirement age, territorial remoteness and difficult accessibility in conditions of informational isolation. The scarcity and difficulty of communication because of the permanent residence of the older generation “on the mainland” outside the Kamchatka peninsula is difficult to consider as a “respectfully mitigating” factor [11]. We absolutely agree with the opinion of O.Yu. Strizhitskaya, M.D. Petrash that a modern person is mobile enough. Often family generations are geographically separated within one country, may be in different countries and continents, but, however, in the era of high information technology this circumstance may not be an objective limitation of communication between a child and grandparents [21].

The importance and significance of a child’s communication with grandparents as one of the dominant factors in forming the image of an ageing person is reflected in some contemporary studies. For example, in the work of A. Flamion et al. (Flamion, et al.,) in a sample of 1,151 Belgian children and adolescents between the ages of seven and sixteen, it was found that frequent and friendly contact with grandparents (more often with grandmothers) correlated with more favorable feelings about older people [31].

The results of another study have shown that for older preschool children with lack of communication with their ancestors, the image of the old person is not personalized and in general represents an assembled construct of “strange old people” or “nobody’s old people” more often according to stereotypical signs of physiological loss and indifferent emotions [36].

Here we cannot ignore the fact that in modern society there is a tendency to use all the possibilities and achievements of bio-technology to maintain the state of “anti-aging”, where the visual image of a person plays a determining role in the perception of an aging person and has the function of contrasting the experience of long life with physical decay [13; 25].

We also support the researchers’ opinion on the role of the family, the significance of the type of family upbringing, the content of communication with significant adults (parents, grandparents) to form a child’s value attitude towards the older generation, as well as its future self-esteem and psychological well-being [16; 35]. The necessity of formation of the child’s attitude towards senior adults and old age people, as an obligatory part of the “child-adult” system, which can act as a primary basis of all kinds of subsequent relations of the child to reality and be the initial condition of the very human existence and intensions of child development, is emphasized in the classical works of the Russian psychologists [3; 5; 8; 27].

In this study, the need to recognize experience, seek compromise, the ability to empathize and understand one’s emotional state during the gerontogenesis stage is prioritized by older respondents to describe their expected attitude through the dominant categories of “understand-respect”. It is likely to be extremely problematic to “teach” such a variant of the attitude of descendants to their ancestors, which essentially is supported by the results of the analysis of the responses from the children’s sample.

The relevant attitude of the elementary schoolchildren to an ageing person is represented through the multi-component category of “pity”. In the etymological dictionary of the Russian language the word “pity” is interpreted as frequently used in the meaning of “I love, I respect”, denoting the context of value, recognition, reverence and compassion [28]. However, we dare to argue that the results of the content analysis of the descriptions of the dominant relational categories in the children’s sample demonstrate attitudes toward the late-age respondents more as neutral-indulgent compassion. The older respondents did not include this children’s choice in the range of agreement with expected attitudes toward them.

The junior schoolchildren less frequently presented examples of their ability to understand the condition of an aging person and readiness to express a sense of appreciation and respect for the experience of a long life, which was confirmed by the older cohort as agreement with the expected attitude to them. In our opinion, this result can be explained by the fact that, despite the transformation of traditional forms of intergenerational interaction, many Russian families consciously support intergenerational communication based on the preservation of socio-cultural traditions of several generations, without losing the ‘codes’ of priority of cultural dialogue and intergenerational continuity.

We support the opinion of some researchers that the older generation has an enormous potential to demonstrate to descendants the possibilities of “mastering the art of life in the context of developing the ability to inspire themselves and others, create their own rhythm and pace of life, enjoy the live human communication, and in general to build a constructive dialogue with the world” [29, p. 85].

Awareness of the importance and respect for the difference of needs in each period of life, the uniqueness of the experience of relations of generational groups, as valuable and obligatory, can be the key to the partnership dialogue of generations and the basis of cultural adaptation to age. Besides, it is necessary to move from sameness to individuality in order to build sustainable and mutually comfortable intergenerational relations, as well as to define the principles on which a universal cultural adaptation to age can be generated [3].

Conclusions

-

The analysis of the questionnaire data specifying the parents’ point of view on the potential experience of their children’s interaction with the generation of late age shows a tendency to a low degree of grandparents’ participation in the period of their grandchildren’s childhood and, in general, represents the picture of deficit of live communication between ancestors and descendants. The reasons for the recorded fact are the territorial remoteness of the older generation, their continued employment, being in the status of a pensioner, and the problems of adult disagreement. Answers of schoolchildren’s parents showed that relations between their children and their parents are increasingly optional, where situational financing of grandchildren along with occasional leisure activities are evaluated as a norm of relations, a reality of modern life.

-

The result of focus-group interviews with elementary schoolchildren allows us to present quantitatively the categories of children’s attitude towards the older generation in the “pity — respect — love — help — tolerate — don’t know” sequence, where only the category “pity” is statistically dominant. Qualitative analysis of the selected category reveals its meaningfulness and multicomponent structure, but statistical significance is revealed by one component, which reflects a descriptive picture of external manifestations of physical incompetence, insecurity and inadaptability to life of an aging person, i.e. “physiological losses”. On the whole, a large part of the children’s sample demonstrates the actual attitude towards the ancestors as a variant of neutral and indulgent compassion and compliance with formal, stereotypically correct norms of behavior, relying on the collective image of the “not personalized” person at a late stage of ontogenesis.

-

In the gerontological cohort the expected attitude of children to them is represented by the significant category “understand — respect”, reflecting the position of extreme importance of recognition of their experience by descendants, search for compromises of interaction, readiness to empathize and to accept the emotional state of the person of late age. This result is also recorded in the data on the agreement of older participants with the children’s options (with a low frequency of choice), demonstrating the continuity of the preservation of the standard of obligatory and valuable behavior of the ancestors. Late-age respondents placed components with the highest frequency of children’s choices which, from the perspective of the older generation, describe attitudes toward them more as condescending compassion in the range of disagreement.

-

The need and readiness of the aging person to mobilize and realize the enormous palette of his life potential to demonstrate to descendants the particular importance of recognizing the uniqueness of each generation’s experience can be a source of complementarity and solidarity between generations as the basis of cultural adaptation to age.

Limitations and Perspectives of the Research

Thinking critically about the results of the presented work, it would be interesting to consider them in the context of the limitations of the research.

So, there was only one parent involved in the child-parent pairing, and for the most part they were mothers. Although some researches confirm a great similarity of children’s views with mothers in the field of intergroup relations [30], we admit that the lack of “gender completeness” of the parental sample can reduce the generalization potential of the parents” questionnaire data.

Another limitation of our study is related to the problem of the difficulty of forming a homogeneous sample, including families with equal age ranges in intergenerational representatives and conditional similarity in economic and sociocultural characteristics.

Relative limitations include the specificity of the sample of older respondents, the composition of which was represented by regular participants of the gerontological art group. Possibly, when only voluntary elderly respondents with preserved activity and motivation participate, information about the less active ageing person is lost, and in our opinion, this circumstance allows for the risk of distortion of the research picture.

Finally, we agree with many researchers who believe that intergenerational relations are a multifaceted, multidimensional phenomenon involving different systems of human relations. The research of separate aspects of this phenomenon also limits the possibility of integral consideration of intergenerational relations [22].

Summarizing all of the above, the authors see the prospect of further research in studying the problem of intergenerational solidarity, both in the family and non-family contexts.

The study of the problem of psychological culture and readiness of the elderly person to a partnership dialogue with the younger descendant can also be relevant.

Another promising area is the possibility of intergenerational cooperation programs focused on the “shaping power” of intergenerational effects and/or intergenerational transmission.

Table 1

Social and Demographic Characteristics of the Older Generation (N=395)

|

Parameters |

Representativeness of grandparents, % |

Fisher’s criterion φ emp. |

|

|

Grandmothers 64,3% |

Grandfathers 35,7% |

5,51 p≤0,01 |

|

|

Age range |

|||

|

Aged 46—55 |

37,4 |

27,6 |

2,16 p ≤0,05 |

|

Aged 56—75 |

48,0 |

58,2 |

1,95 p ≤0,05 |

|

Aged 76 and older |

14,6 |

14,2 |

0,13 |

|

Level of education |

|||

|

Incomplete secondary education |

1,6 |

2,1 |

0,26 |

|

General secondary education |

20,5 |

31,2 |

2,31 p≤0,01 |

|

Specialized secondary education |

35,8 |

32,6 |

0,65 |

|

Higher education |

42,1 |

34,1 |

1,67 p ≤0,05 |

|

Marital status |

|||

|

Married |

30,3 |

39,7 |

2,35 p≤0,01 |

|

Divorced |

46,7 |

47,5 |

0,15 |

|

Widow(er) |

22,9 |

12,8 |

2,52 p≤0,01 |

|

Social status |

|||

|

Employed |

64,5 |

54,6 |

1,91 |

|

Not working |

35,5 |

45,4 |

1,9 |

Fig. 1. Comparison of the frequency of choices and the format of children’s (non)communication with their grandparents

Fig. 2. Comparison of the frequency of selection of family types by degree of use of the grandparents’ care/upbringing support

1 The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the help of students from the Faculty for Psychology and Pedagogy at Vitus Bering Kamchatka State University for recording the stenographs.

Table 2

Comparison of the “Attitudes” Categories Choice Frequency in the Group of Junior Schoolchildren

and Older Respondents

|

Categories |

Choice frequency (the quantity of responses — %) |

Fisher’s criterion, φ |

|||

|

Junior schoolchildren (n=122) |

Older generation (n=40) |

||||

|

Quantity |

% |

Quantity |

% |

||

|

Pity |

115 |

70,9 |

14 |

10,9 |

10,8 p≤0,01 |

|

Respect |

17 |

10,5 |

35 |

27,3 |

3,1 p≤0,01 |

|

Love |

13 |

8,1 |

9 |

7,0 |

0,24 |

|

Understand |

0 |

0 |

37 |

28,9 |

9,6 p≤0,01 |

|

Honour |

0 |

0 |

18 |

14,1 |

6,5 p≤0,01 |

|

Help |

8 |

4,9 |

10 |

7,8 |

1,1 |

|

Tolerate |

4 |

2,5 |

5 |

3,9 |

0,7 |

|

Do not know |

5 |

3,1 |

0 |

0 |

2,9 |

Table 3

Frequency Distribution of the Components of the Attitude Category “Pity”

in the Group of Elementary Schoolchildren

|

Frequency of choice, % |

Components |

Examples of children’s responses2 |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

38,8 |

“Physiological loss” reflects a descriptive picture of the external manifestations of low physical (bodily) competence and destruction, as well as insecurity and maladjustment to life in old age |

‘their teeth fall out and they don’t chew well, they don’t eat much and they stop growing’ ‘some have amnesia, I don’t know what it is, but mum says that a lot’, ‘they are slow, forget everything and can even be dumb’ ‘they don’t sleep well at night and during the day have a cat-nap, so mum scolds us if we make noise and disturb the old granny, oh actually great granny’ ‘they have poor health and so they can’t do some things themselves, then they get angry and may call you bad names or even punish you. For example, I saw my friend’s grandma Ira cursing loudly and hitting the cat because she forgot to close the door to the room with the computer herself.’ ‘they are old and their eyesight is bad, they walk slowly and if there, for example, they are crossing the road and a car is coming with broken brakes, we have to rush straight to them so that they don’t get hit by a car’ |

|

12,5 |

“It is the way things are done” demonstrates pupils’commitment to formally following socially accepted notions of stereotypes of old age and norms of behaviour with an adult |

‘one just should feel sorry for the elderly, one should be polite to them, shouldn’t he or she?’ ‘one shouldn’t offend the elderly, that’s the rule of politeness’ ‘they’re at the age when all they need is help, sympathy and compassion’ ‘they are old and may even be veterans we just have to respect them at least out of politeness, that’s what my mother says and I’ve seen other adults and even children say this on TV’ |

|

11,6 |

“Our duty” explains the child’s position as a conscious, voluntary, internally accepted obligation to help, to protect the ageing person |

‘they have lived long and fought for our freedom’ ‘[they are]elderly veterans, and it’s hard for them to bear the hardships of life’ ‘they defended our country’ ‘many of them are veterans, if it weren’t for them we wouldn’t exist’ ‘they’re special to us’ ‘they’ve lived their lives, and maybe some have fought, and we have to pay good for good, we have to help them’ ‘it’s just that we’re younger than them, we should do that’ |

|

11,2 |

“Empathy” demonstrates a child’s ability to understand and experience the emotional states experienced by an older person |

‘daddy often scolds granny because she tortures him with clever advice. She then cries quietly for a long time, but I always hear and then I cry, I feel very sorry for my grandmother’; ‘bus drivers shout at old people because they are slow, it takes a long time to climb the steps. And also when there is a heavy snowstorm they are so wet, they don’t smell good, it’s difficult for them to walk in the snow and then sweep the snow up to the entrance of the bus, moreover they cannot reach their bodies everywhere. It offends me to watch them being beknaved and laughed at by some children’ |

|

8,9 |

“Financial insecurity”” combines statements reflecting children’s ideas about the importance and significance of material well-being and the risks of living in old age in cases of disadvantage |

‘they don’t get paid enough money, they don’t have enough money to feed themselves’; ‘they don’t have enough money or food. They are older than us and poorer than us’ ‘they don’t earn, so they always have little money for medicine’ ‘they can be cheated, their flat can be taken away or they can be kicked out of the house. Old grannies are often homeless, skinny, poorly dressed, smell bad’ ‘old people are not in good health and not as well off as my dad, they have a tiny pension’ |

|

8,0 |

“The finitude of life” reflects the students’ thoughts, feelings and rather regrets about the imminent impending irrevocability of life’s journey |

‘they might fall and crash or die altogether’ ‘they might become totally ill’ ‘they’re almost out of strength and they’re just a little bit away from death’ ‘their heart could stop and then that’s it, they don’t have any more life’ ‘well, because they’re old and have to die soon and they’ve done their schooling and they’ve done their time and they’ve lived a long time’ |

|

6,3 |

“Gratitude” represents a picture of a child’s sense of gratitude to the older generation for the experience of a long life |

‘to live longer and please us’ ‘they’re the oldest, they can correct mistakes’ ‘because they’re not young anymore, but they can still be kind’ ‘they can always give useful advice’ ‘they know much more than we do. We should also pity old people out of gratitude, because they are our parents’ parents, or even our great-great-grandparents, which means that if it wasn’t for them, we wouldn’t exist, and that’s for sure’ ‘old people are our ancestors’ ‘they’re older than us, they’ve conquered trouble or sorrow many times, I think they know how to live right’ ‘they have a long age and many interesting stories about it’ ‘they like to hear our good attitude towards them’ |

|

2,7 |

“Modelling one’s old age period” brings together statements reflecting children’s ideas about their lives in old age |

‘what if I’m in this situation’ ‘if we hurt the elderly, we’ll be treated as badly in our old age’ ‘because there’s no cure for wrinkles and forgetting’ ‘I’m not afraid to be that old. I will study well, then I will be a doctor, I will find cream and injections for old people so that they can do different things for themselves for a long time and enjoy themselves’ ‘We are also growing and our body is with us, so one day I will be old, I don’t want to be hurt’ |

2 We preserved the semantics and grammar of the children’s utterances

Table 4

Representation of the “Understand —Respect” Attitude Category in a Gerontological Sample

|

Frequency of specifying judgments, % |

Examples of responses2 |

|

39,3 — the need for recognition of one’s experience and merits |

‘it is important that my grandchildren are proud of me’; ‘I am praised by my grandchildren and their friends’; ‘getting compliments from young people’ |

|

36,3 — the need for seeking compromise |

‘noted for me the possibilities of modernity, familiarity with which would enable me to keep up with the times’; ‘well, if they themselves discuss the details of their lives with me, I am happy, and it saves me from DEpression, DEmentia and many other DE-old men, about whom so many scientists write and speak’ |

|

24,4 — ability to empathize and understand the emotional state |

‘taking more interest in my emotional stress’; ‘letting me admire them, trusting me that I am not the enemy of their happiness and their whole life’; ‘so my granddaughter won’t be shy about inviting me into her company’ |

Fig. 3. Ratio of degree of (dis)agreement by older respondents with components of the children’s category “pity”

3 The semantics and grammar of the respondents' statements are preserved.

References

- Ambarova P.A. Obrazovatelnye strategii v structure modeli «uspeshnogo» starenia [Education strategies in the structure of «successful» aging model]. Materialy Tretiey mezhdunarodnogo foruma «Cognitive Neuroscience — 2020» (g. Ekaterinurg, 11—12 dekabrya 2020 g.) [Proceedings of the Third International Forum «Cognitive Neuroscience — 2020»]. Yekaterinburg: Publ. Ural Univ. Press, 2021, pp. 56—60. Available at: https://elar.urfu.ru/handle/10995/95455 (Accessed:10.04.2021). (In Russ.).

- Barsukov V.N., Shabunova A.A. Trendy izmenenia trudovoy aktivnosti starshego pokolenia v usloviyah starenia naselenia [Trends of changes in labor activity in elderly in conditions of population aging]. Problemy razvitiya territorii [Problems of areas development], 2018, no. 4(96), pp. 87—103. DOI:10.15838/ptd.2018.4.96.6 (In Russ.).

- Biggs S., Haapala I. Dolgaya zhizn’, vzaimoponimanie i empatia pokoleniy /Per. s angl. A.A. Ipatovoj [Long life, mutual understanding and generations’ empathy]. Monitoring obshchestvennogo mneniya: Ekonomicheskie i social’nye peremeny [Monitoring of social opinions: economic and social changes], 2016. no. 2. pp. 46—58. DOI:10.14515/monitoring.2016.2.03 (In Russ.).

- Bulanova D.D. Rol’ starshego pokoleniya v vospitanii doshkolnikov [The role of older generation in preschoolers upbringing]. Nauchnoe otrazhenie [Scientific reflection], 2017. no. 4(8), pp. 9—11.(In Russ.).

- Vygotsky L.S. Psykhologia razvitiya cheloveka [Psychology of human development]. Moscow: Smysl, 2003. 1136 p.(In Russ.).

- Gorlin Yu.M., Lyashok V.Yu., Maleva T.M. Povysheniye pensionnogo vozrasta: pozitivnye effekty i veroyatnye riski [Prolongation of retirement age: positive effects and possible risks]. Ekonomicheskaya politika [Economic policy], 2018, no. 1, pp. 148—179. (In Russ.).

- Yelutina M.E. Chekanova E.E. Socialnaya gerontologia [Social gerontology]. Moscow: Infra, 2004. 157 p. (In Russ.).

- Zaporozhets A.V. Izbrannye psykhologicheskie trudy [Selected papers]. Moscow: Direct-Media, 2008. 1287 p. (In Russ.).

- Krasnova O.V. Rol’ babushka: sravnitelnyy analis [The role of a grandmother: a comparative study]. Psihologiya zrelosti i stareniya [Psychology of adulthood and elderly], 2000, no. 2, pp. 89—114. (In Russ.).

- Krasnova O.V. Eidjism v rabote s pozhilymilud’mi [Ageism in the work with old people]. In O.V. Krasnova, A.G. Liders (eds) Psikhologia starosti i starenia [Psychology of elderly and aging]. Moscow: ACADEMA, 2003, pp. 354—362. (In Russ.).

- Kulik A.A. Specifika obraza zhizni ludey, prozhivayushih v slozhnyh klimatogeographycheskih usloviyah [Specific life of people in difficult climatic and geographic conditions] Vestnik Kemerovskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta [Journal of Kemerovo State University, 2020], no. 22(1), pp. 139—151. DOI: 10.21603/2078-8975-2020-22-1-139-151 (In Russ.).

- Naumova V.A. Dialog pokoleniy: kulturno-istoricheskiy podhod [Dialogue of generations: cultural-historical approach]. Materialy Pervogo Mezhdunarodnogo simpoziuma po kul’turno-istoricheskoj psihologii«Aktual›nye problem kul’turno-istoricheskoj psihologii» (Novosibirsk, 17—19 noyabrya 2020)[Proceedings of the First International Symposium on Cultural-Historical Psychology «Actual Problems of Cultural-historical Psychology»]. Novosibirsk: Pedagogical Univ. Press, 2020, pp. 45—57. (In Russ.).

- Nazimova A. Aktivnoye dolgoletiye I vneshniy vid: kak teoreticheskaya kontseptsiya reguliruyet samovospriyatiye v starchem vozraste) [Active longevity and appearance: how theoretical conception regulates self-perception in elderly?] Zhurnal issledovanij social’noj politiki [Journal of social policy studies], 2016. Vol. 14, no. 4, pp. 569—582. Available at: https://jsps.hse.ru/issue/view/268 (Accessed 10.04.2021).(In Russ.).

- Pensionnaya reforma v Rossii [Elektronnyj resurs] [Pension reform in Russia]. Available at: http:/pensiya.molodaja-semja.ru/reforma/ (Accessed 10.04.2021). (In Russ.).

- Polivanova K.N. Detstvo v menyayushemsya mire [Childhood in the changing world] Sovremennaya zarubezhnaya psihologiya = Contemporary foreign psychology, 2016. Vol. 5. no. 2. pp. 5—10. DOI:10.17759/jmfp.2016050201 (In Russ.).

- Postnikova M.I. Mezhpokolennye otnoshenia v kontekste kulturno-istoricheskoy kontseptsii [Relationships between generations through cultural-historicaltheory]. Mir nauki, kul’tury, obrazovaniya [Worldofscience, culture, education], 2010, no. 4(23), pp. 125—128. (In Russ.).

- Smirnova E.O., Smirnova S.Yu., Sheina E.G. Roditel'skie strategii v ispol'zovanii det'mi cifrovyh tekhnologij [Parental strategies in the use of digital technologies by children]. Sovremennaya zarubezhnaya psihologiya = Modern foreign psychology, 2019, Vol. 8, no. 4, pp. 79—87. DOI: 10.17759/ jmfp.2019080408.

- Soldatova G.U. Tsyfrovaya socializatsiya v kulturno-istoricheskoy paradigm: izmenyayushiysa rebenok v izmenyayushemsya mire [Digital socialization through cultural-historical paradigm: a changing child in a changing world]. Social'naya psihologiya I obshchestvo = Social psychology and society, 2018, Vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 71—80. DOI:10.17759/sps.2018090308 (In Russ.).

- Soldatova G.U., Vishneva A.E. Osobennosti razvitiya kognitivnoj sfery u detej s raznoj onlajn aktivnost'yu: est' li zolotaya seredina? [Features of cognitive development in children with different online activity: is there a golden mean?]. Konsul'tativnaya psihologiya i psihoterapiya = Counseling psychology and psychotherapy, 2019, Vol. 27, no. 3, pp. 97—118. DOI: 10.17759/cpp.2019270307

- Starchikova M.V. Adaptivnye strategii lits pozhilogo I starcheskogo vozrasta v kontexte mezhpokolennogo vzaimodeistviya [Adaptive strategies in the late and old age through the context of generations interactions]. Izvestiya Altajskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta [News of Altaisk State University], 2010, no. 2(2), pp. 127—130. (In Russ.).

- Strizhitskaya O.Yu., Petrash M.D. Nesemeynye mezhpokolennye otnoshenia: problem i perspektivy [Family unrelated relations of generations: problems and perspectives] Vestnik Sankt-Peterburgskogo universiteta. Psihologiya [Journal of Saint Petersburg University,Psychology], 2019а. no. 9(3), pp. 243—253. DOI:10.21638/spbu16.2019.302 (In Russ.).

- Strizhitskaya O.Yu., Petrash M.D. Metodologicheskiye problem I podhody k empiricheskomu issledovaniy u mezhpokolennyh otnosheniy [Methodological problems and approaches to an experimental study of relations between generations Mir nauki. Pedagogika I psihologiya [World of science. Pedagogics and Psychology], 2019б, no. 6. Available at: https:// mir-nauki.com/PDF/108PSMN619.pdf (Accessed10.04.2021). (In Russ.).

- Symanuk E.E., Bukovey T.D., Zeer E.F. Transvitalnost’ kak factor preodoleniya krizisa utratyprofessii [Trans vitality as a factor for surmounting the crisis of profession loss]. Materialy Tret`ego Mezhdunarodnogo foruma «Cognitive Neuroscience — 2020» (g. Ekaterinurg, 11—12 dekabrya 2020 g.). [Proceedings of the III International Forum «Cognitive Neuroscience — 2020»].Yekaterinburg: Publ. Ural Univ. Press, 2021, pp. 88—91. Available at: https://elar.urfu.ru/handle/10995/95455 (Accessed:10.04.2021).(In Russ.).

- Taikova L.V., Taikov S.M. Problema mezhpokolenny otnosheniy v sovremennom obshestve I semye [Problem of relations between generations in the contemporary society and family]. Vestnik Novgorodskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta [Journal of Novgorod State University], 2015, no. 88. pp. 92—95. (In Russ.).

- Chenyshkova E.V. Vizualnyy obraz starosti v kontekste sovremennoy zhizni [Visual image of elderlyin modern life]. Nauchnye problem gumanitarnyh issledovanij [Scientific problems of humanitarian studies], 2011, no. 9. pp. 288—293. (In Russ.).

- Sharin V.I., Kul’kova I.A. Vliyanie pomoshi starshego pokoleniya na rozdayemost’ v Rossii [The effect of older generation help on nativity in Russia]. Narodonaselenie [Population], 2019, no. 2. pp. 40—50. DOI:10.24411/1561-7785-2019-00014. (In Russ.)

- Elkonin D.B. Psykhicheskoye razvitiye v detskih vozrastah [Child mental development in different age]. Moscow: Institute of practical psychology press; Voronezh: Modek press. 1995, 415 p.(In Russ.).

- Etimologicheskiy onlain slovar’ russkogo yazika M. Fasmera [Elektronnyjresurs] [M. Fasmer’s Etymological on line dictionary of Russian]. Available at: https://lexicography.online/etymology/vasmer/ (Accessed10.04.2021) (In Russ.).

- Yafalyan A.F. Esteticheskoye samovyrazhenie detey v usloviyakh mezhpokolencheskogo dialoga [Esthetic self-expression of children in conditions of dialogue between generations]. Pedagogicheskoe obrazovanie v Rossii [Pedagogical education in Russia], 2017, no. 12. pp. 80—86. (In Russ.).

- Flamion A., Missotten P., Jennotte L., Hody N., Adam S. Old Age-Related Stereotypes of Preschool Children. Front. Psychol, 2020. Vol. 11, pp. 807. DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00807

- Flamion A., Missotten P., Marquet M., Adam, S. The influence of contacts with grandparents on the views of children and adolescents on the elderly. Child of Dev, 2019. Vol. 90(4), pp. 1155—1169. DOI:10.1111/cdev.12992

- Hsieh H.F., Shannon S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005. Vol. 15(9). pp. 1277—1288. DOI:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Levy B.R, Myers L.M. Preventive health behaviors influenced by self-assessment of aging. Preventive medicine, 2004. Vol. 39(3), p. 625. DOI:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.029.

- Levy B.R. The embodiment of the stereotype: A psychosocial approach to aging. Current trends in psychological Science, 2009. Vol. 18(6). pp. 332—336. DOI:10.1111/j.1467—8721.2009.01662.x.

- Mendonsa J., Marquez S., Abrams D. Children's attitudes toward the elderly: Current and future directions. In Ayalon L., Tesch-Römer C. (eds.), Contemporary Perspectives on Ageism. International Perspectives on Aging, 2018. Vol. 19. pp. 517—548. DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8_30

- Naumova V.A., Glozman J.M. Representations of old age in childhood. Lurian Journal, 2021. Vol. 2(1), pp. 63—79. DOI:10.15826/Lurian.2021.2.1.4

- Rowe J.W., Kahn R.L. Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 1997. Vol. 37(4), pp. 433—440. DOI:10.1093/geront/37.4.433.

- Strizhitskaya O. Aging in Russia. The Gerontologist, 2016. Vol. 56(5), pp. 795— DOI:10.1093/geront/gnw007.

- Tornstam L. Gerotranscendence. A Developmental Theory of Positive Aging. New York: Springer, 2005. 226 p. URL: http:/repositorii.urindo.ac.id/repository2/files/original/94bf151af9fff10ee512fe9032b10e5536cb401a.pdf (Accessed 10.04.2021).

- Vauclair C.M., Rodrigues R.В., Marques S., Esteves C.S., Cunha F., Gerardo F. Doddering but deareven in the eyes of young children? Age stereotyping and prejudice in childhood and adolescence. Int. J. Psychol, 2018. Vol. 53, pp. 63—70. DOI:10.1002/ijop.12430.

Information About the Authors

Metrics

Views

Total: 1183

Previous month: 58

Current month: 28

Downloads

Total: 212

Previous month: 6

Current month: 1