Psychological Science and Education

2022. Vol. 27, no. 4, 88–99

doi:10.17759/pse.2022270409

ISSN: 1814-2052 / 2311-7273 (online)

The Current State of Emergency Psychological Assistance in the Education System

Abstract

General Information

Keywords: emergency psychological assistance, crisis situation, education system, crisis state, monitoring study, school, mental health

Journal rubric: Educational Psychology

Article type: scientific article

DOI: https://doi.org/10.17759/pse.2022270409

Received: 23.05.2022

Accepted:

For citation: Ulyanina O.A., Gayazova L.A., Ermolaeva A.V., Faizullina K.A. The Current State of Emergency Psychological Assistance in the Education System. Psikhologicheskaya nauka i obrazovanie = Psychological Science and Education, 2022. Vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 88–99. DOI: 10.17759/pse.2022270409.

Full text

Introduction

The research community has focused on the psychological consequences of crisis situations. A crisis situation in an educational organization is an incident that causes harm to the life and health of those involved in educational relationships, the environment, the organization, the educational process, the image of the school, etc. [4; 9; 15].

Crisis situations in which the life and health of significant numbers others is threatened, media coverage of tragic events is susceptible, others are emotionally destabilized, children are forced to change their living conditions, significant social contacts are severed, etc. are a particular danger to the psychological state of those involved. [3; 5; 10].

An analysis of foreign studies has made it possible to identify common symptoms in children that manifest themselves in all aspects of personality and persist long after the crisis event. The symptoms in the emotional sphere are pronounced anxiety, borderline panic, and a state of fear. The symptoms in the cognitive sphere are a decrease in the level of cognitive processes, fixation on the experiences and the events that led to the crisis condition, and the inability to focus on positive events. The symptoms in the behavioral sphere are avoidance of any crisis situation involving chaotic movement, agitation toward impulsive aggression with the necessity to discharge it externally to lethargy and stupor. The symptoms in the somatic sphere are chronic painful sensations in the body, sleep disturbances, decreased appetite, a somatic vegetative state, and conversion reactions. The symptoms in the mental sphere are psychosensory disorders, feeling of an altered self and environment, depersonalization, and derealization. [13; 14; 15].

The system of emergency psychological assistance (hereinafter EPA) in the educational environment is a system of measures to provide psychological assistance, depending on the type of crisis event in which the participants of educational relations have found themselves, whether in a situation of explicit or implicit threat to their life and health [2].

Research program

In order to study the current state of emergency psychological assistance in the education system of the Russian Federation, a monitoring study was conducted in January 2022 by the Moscow State University of Psychology and Education.

Monitoring tasks:

1. Assessment of the infrastructure for providing emergency and crisis psychological assistance to students and their parents (legal representatives).

2. Gathering information on staffing for emergency and crisis psychological assistance in the education system.

3. Identification of conditions that negatively affect the quality and availability of emergency and crisis psychological assistance for students and their parents (legal representatives).

4. Identification of areas in the education system that require the development of psychological services with regard to the provision of emergency and crisis psychological assistance to students and their parents (legal representatives).

The information-gathering technology used for the monitoring included a survey of three groups of respondents:

— Executive authorities of administrative divisions of the Russian Federation (hereinafter referred to as EAs), responsible for education and supervising the psychological service provided in education (62 subjects of the Russian Federation);

— heads of centers of psychological, pedagogical, medical and social assistance subordinate to theEAs, engaged public administration in the field of education (426 representatives of regional and municipal centers providing psychological, pedagogical, medical and social assistance in 70 administrative divisions of the Russian Federation);

— teacher-psychologists and psychologists working in the centers providing psychological and pedagogical, medical and social assistance and educational organizations subordinate to the EAs, carrying out public administration in the field of education (11,560 specialists from state and municipal educational organizations and centers providing psychological and pedagogical, medical and social assistance in 75 administrative divisions of the Russian Federation).

Specific questionnaires were developed for each group of respondents.

Results

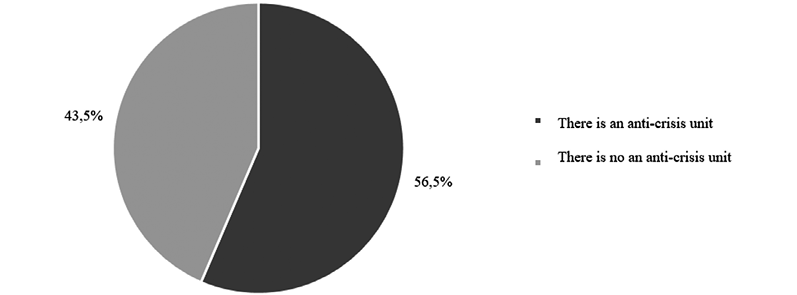

In most of the regions monitored, permanent anti-crisis units have been set up to provide EPA to participants in educational relations in emergency and crisis situations (fig. 1).

There are permanent anti-crisis units in all regions of the Urals Federal District.

There are no such facilities in most of the administrative divisions of the Far Eastern and North-Western districts. This was confirmed by representatives of 6 regions out of 8 in the Far Eastern Federal District.

In regions where there are no permanent anti-crisis units, their functions are performed by:

— the crisis center at a psychiatric hospital (Tula region);

— units of the Ministry of Emergency Situations of Russia (Tomsk, Murmansk regions, Kamchatka Krai);

— units providing remote psychological assistance (children’s trust line) (Vladimir, Kirov regions);

— PPMS-centers (center for psychological, pedagogical, medical and social assistance) (Pskov, Orel, Kaluga, Sakhalin Regions, Republic of Buryatia, Primorsky Krai, Nenets Autonomous Okrug);

— centers of practical psychology and psychological and pedagogical rehabilitation (Moscow, Novosibirsk regions, Kabardino-Balkarian Republic);

— basic psychological offices (Chukotka Autonomous Okrug).

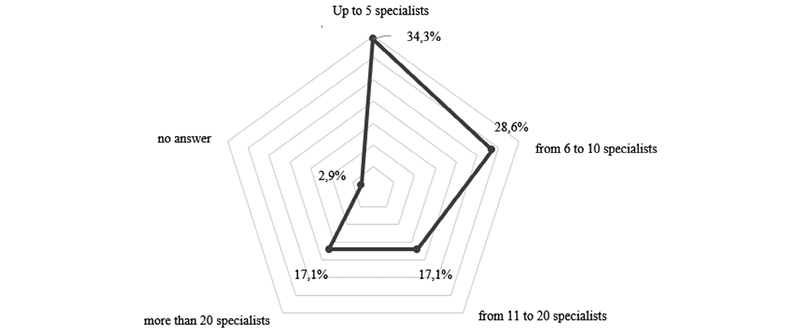

The total number of anti-crisis specialists varies from 3 to 118 people (Fig. 2). The number exceeds 100 people (116 and 118 specialists, respectively) in only two regions of the Volga Federal District (Samara Region and the Udmurt Republic). Anti-crisis units are represented by several organizations in these regions.

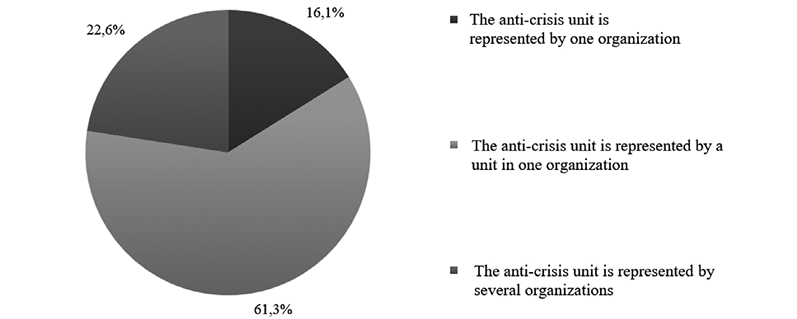

The structure of anti-crisis units for the provision of EPA to students can be: one organization, a unit within one organization, or several organizations.

According to the monitoring data, the most common option is for an anti-crisis unit to be represented by a structural unit within one organization (fig. 3.)

The respondents were asked to list the procedure for actions at the level of the EA, which carries out public administration in the field of education, to provide EPA to participants of educational relations in crisis and emergency situations.

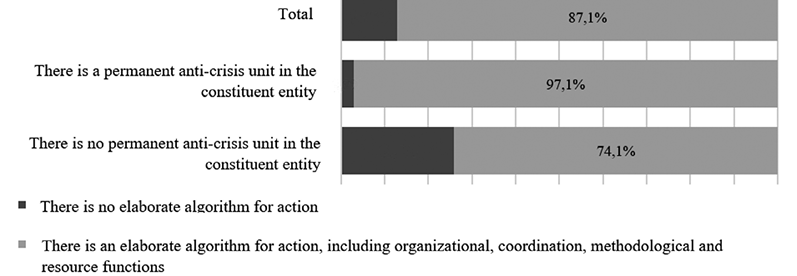

According to the monitoring data, a well-developed algorithm of actions to provide EPA, including organizational, coordination, methodological and resource-allocation functions, exists in the majority of administrative divisions of the Russian Federation (fig. 4.). Among the subjects with permanent anti-crisis units, the share of those with a fully developed algorithm for the provision of EPA is higher.

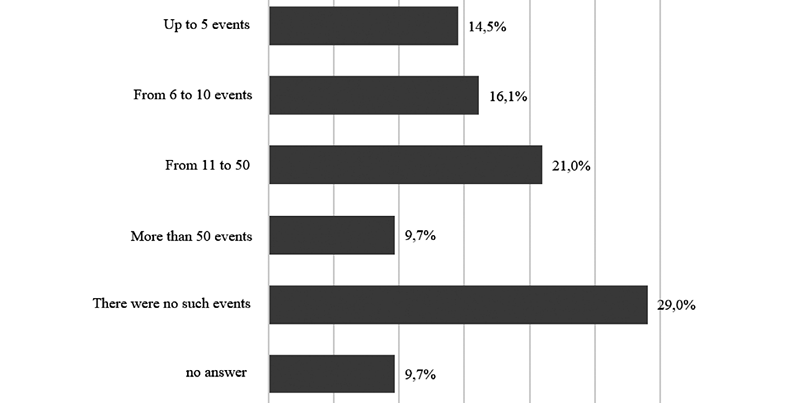

Every fifth administrative division recorded between 10 and 50 emergencies/crisis situations in which EPA was provided at the level of the administrative division of the Russian Federation (fig. 5). Although the number of regions with a high risk of such situations is low overall (6 regions), the high frequency of this indicator is alarming.

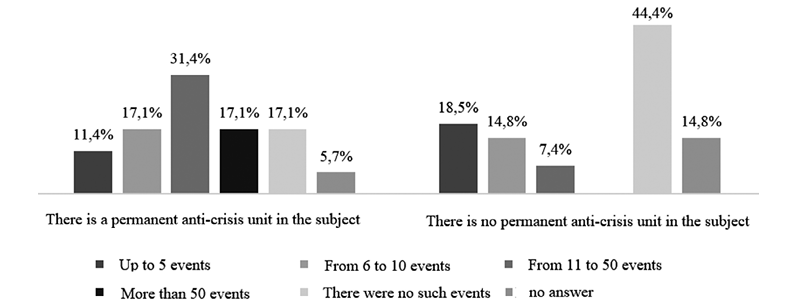

Regions with no crisis events in the last 5 years are more likely to have no permanent anti-crisis units for EPA than regions with more than 10 such events (fig. 6).

In emergencies/crisis situations, staff from PPMSs are involved in the provision of EPA.

It was asked to assess whether the professionals at the PPMSs provided assistance in each of the 5 types of events in 2021.

Two armed attacks were recorded in educational institutions, and EPA for the students, their parents (legal representatives) and teaching staff was provided by specialists from the PPMS-centers of Moscovsky district of St. Petersburg and the Rostok Center for Psychological and Pedagogical Rehabilitation and Correction (Kazan).

Suicide/suicide attempts by students. EPA was provided in this situation at 138 organizations (32% of the total number of PPMSs). As a rule, these were single cases (11%), or 2—3 cases (9%) during 2021.

In situations of violence against students, EPA was provided at 72 organizations (17% of the total number of PPMS-centers).

In conflict situations among students, parents (legal representatives), or pedagogical staff, EPA was provided at 200 organizations (47% of the total number of PPMSs). According to respondents’ estimates, in 2021, specialists had to work with 2—3 such cases (15%), or some, less often, with 4—5 cases (10%).

At 17 organizations EPA was provided to accompany mourning events (8% of the total number of PPMS-centers). As a rule, these were single cases in 2021 (1 case — 4%, 2—3 cases — 3%).

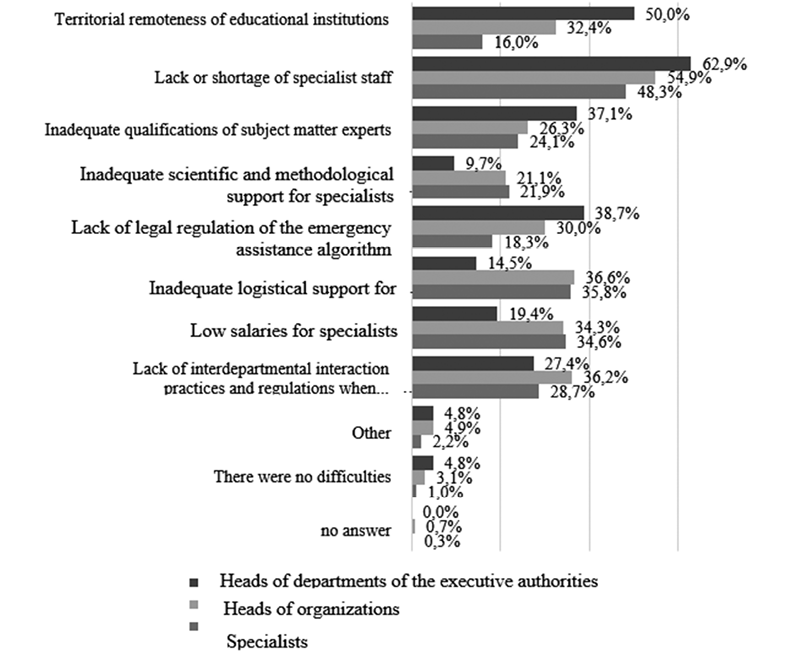

When providing EPA, various difficulties may arise at the regional level, at the level of the organization, or that of a specific specialist (fig. 7).

All respondents cited a lack of specialist staff as a major challenge in the provision of EPA.

For the heads of EAs responsible for state administration of education, the second most important difficulty is related to the territorial remoteness of educational organizations. Heads of PPMC-centers and psychologists note an insufficient level of material and technical support for psychological services (37% and 36% respectively).

Heads and specialists of PPMS-centers are concerned about low salaries (34% and 35%); for the majority of Eas, this is not a factor significantly complicating the provision of EPA for the participants of educational relations (19%).

EAs indicated a lack of legal regulation or an algorithm for EPA provision in the education system — 40%. The figure is 30% among heads of organizations, and for specialists it is 18%. Lack of practice and regulation in interdepartmental interaction hinders the organization of EPA primarily for the heads of organizations (PPMS-centers) — 36%, less frequently for specialists (29%) and EAs (27%).

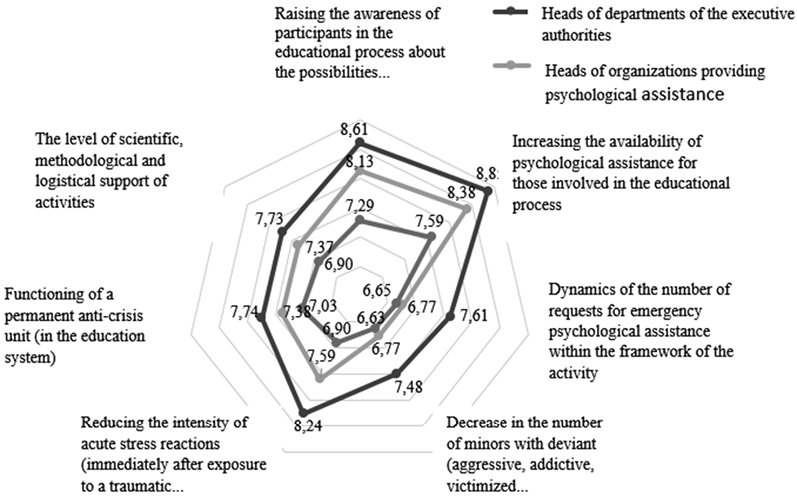

The monitoring participants assessed to what extent the proposed criteria reflect the quality of emergency psychological assistance on a 10-point scale.

All participants gave a high score to the criterion of “increasing the level of accessibility of psychological assistance for participants in the educational process who find themselves in crisis and emergency situations”. The EAs assessed this at 8.85 points. (fig. 8).

The heads of organizations providing psychological assistance to the population assessed it at a level of 8.38 points.

Specialists providing psychological assistance to children and their parents (legal representatives) assessed this criterion as high as possible (7.59 points). The highest scores were given by specialists from the North-Western (7.8 points), Ural and Central (7.7 points each) federal districts. The lowest score for this criterion was given in the North Caucasus Federal District, which generally correlates with the scores from the EAs.

Second place was given to the criterion “raising awareness of participants in the educational process about the possibilities of seeking appropriate assistance in crisis and emergency situations”. Four regions gave a high score to the criterion “raising public awareness about the services provided by psychological centers in crisis and emergency situations” (above 9.0 points): the Siberian, Far Eastern, Northwestern and Ural Federal Districts, while in the North Caucasus Federal District, the EAs assessed this criterion only at 7 points.

The criterion “reduction of the intensity of acute stress reactions in victims, optimization of their current mental state” was assessed ambiguously by the participants. Heads at all levels put this criterion in the third place, but experts placed it only in 5th place.

The criterion “functioning of a permanent anti-crisis unit (in the education system) in each constituent entity of the Russian Federation” was ranked at 4th place by heads of all levels, while specialists ranked it in the 3rd place.

Not all subjects of the Russian Federation have permanent anti-crisis units within the education system. There are those who can speak with certainty about the impact of the existence of such units on the quality of EPA provision, and those who can only assume it would be so. The scores obtained for this criterion also show differences depending on region.

According to the results of a survey of the EAs, the assessment of the criterion “the level of scientific, methodological and logistical support for the activities of specialists of the anti-crisis unit” varies from 8.9 points in the Far Eastern Federal District to 5.6 points in the North Caucasus Federal District. Also, a spread in assessments was noted in the survey of heads of organizations providing psychological assistance: from 8.7 points in the Far Eastern Federal District to 6.8 points in the Siberian Federal District.

Specialists providing psychological assistance ranked the criterion reflecting the quality of EPA provision 4th, with average scores ranging from 7.1 to 6.6 depending on the region, indicating a consistency of scores.

For EAs, the criterion “dynamics of referrals to free anonymous services” reflects the quality of the provision of EPA at an average level of 7.6.

In a survey of heads of organizations providing psychological assistance, scores for the criterion reflecting the quality of the provision of EPA ranged from 7.2 (Far Eastern Federal District) to 5.9 (Southern Federal District).

The criterion reflecting “a decrease in the number of minors with deviant and delinquent behavior in comparison with the previous period in the region” placed last.

Fig. 1. Availability of permanent anti-crisis units in subjects of the Russian Federation

Fig. 2. Distribution of anti-crisis units by the number of full-time specialists

Fig. 3. Distribution of anti-crisis units by organizational structure

Fig. 4. Bar charts showing the presence in the administrative divisions of the Russian Federation of a well-developed algorithm for providing emergency psychological assistance

Fig. 5. Number of events in the last 5 years that required psychological emergency assistance

Fig. 6. Distribution of regions by availability of permanent anti-crisis units according to the number of events in the last 5 years that require the provision of EPA

Fig. 7. Difficulties encountered when providing EPA in crisis and emergency situations

Fig. 8. Assessing the quality of emergency psychological assistance

Findings

Four criteria define the quality of the provision of EPA:

— Increasing the availability of psychological assistance to education participants in crisis and emergency situations;

— increasing awareness among participants in the educational process of the possibilities for seeking appropriate assistance in crisis and emergency situations;

— reduction of the intensity of acute stress reactions (immediately after exposure to the psychologically traumatic event) in victims, normalization of their current psychological state;

— functioning of a permanent anti-crisis unit (in the education system) in each administrative division of the Russian Federation.

Experience and analysis of successful practices [8; 11] show that the effectiveness of EPA work largely depends on the availability of qualified specialists [1]. In the education system, there is a need not only to increase the number of trained specialists providing EPA, but also to conduct large-scale educational work with teachers of educational organizations to develop knowledge and skills in the early detection of crisis situations and the provision of first psychological assistance to those participants of the educational process in need [6; 7].

References

- Artamonova E.G., Vasil’eva N.N., Glazunova E.A. Sozdanie i obespechenie sistemy ekstrennoi psikhologicheskoi pomoshchi v sostave psikhologicheskoi sluzhby v sisteme obrazovaniya Rossiiskoi Federatsii [Creation and provision of a system of emergency psychological assistance as part of the psychological service in the education system of the Russian Federation]. Obrazovanie lichnosti [Personal education], 2021, no. 3—4, рр. 95—137. (In Russ.).

- Baeva I.A., Gayazova L.A., Kondakova I.V., Laktionova E.B. Psikhologicheskaya bezopasnost’ lichnosti i tsennosti podrostkov i molodezhi [Psychological security of personality and values of adolescents and youth]. Psikhologicheskaya nauka i obrazovanie = Psychological Science and Education, 2020. Vol. 25, no. 6, рр. 5—18. (In Russ.).

- Burlakova N.S. Psikhicheskoe razvitie detei, perezhivshikh massovye bedstviya: ot izucheniya posledstvii k proektirovaniyu razvitiya na osnove kul’turno-istoricheskogo analiza [Psychodynamics of the transmission of traumatic experience from generation to generation in the context of cultural and historical clinical psychology]. Natsional’nyi psikhologicheskii zhurnal [National Psychological Journal], 2018, no. 1(29), рр. 17—29 (In Russ.).

- Bykhovets Yu.V., Padun M.A. Lichnostnaya trevozhnost’ i regulyatsiya emotsii v kontekste izucheniya posttravmaticheskogo stressa [Personal anxiety and emotion regulation in the context of the study of post-traumatic stress]. Klinicheskaya i spetsial’naya psikhologiya = Clinical and special psychology, 2019, no. 1, рр. 78—89. (In Russ.).

- Golubeva O.Yu. Organizatsiya okazaniya ekstrennoi psikhologicheskoi pomoshchi postradavshim v chrezvychainykh situatsiyakh [Organization of emergency psychological assistance to victims in emergency situations]. Materialy nauchno-prakticheskoi konferentsii «Mezhdistsiplinarnye podkhody k izucheniyu psikhicheskogo zdorov’ya cheloveka i obshchestva» [Materials of the scientific-practical conference “Interdisciplinary approaches to the study of the mental health of a person and society”], 2019, рр. 36—43. (In Russ.).

- Karapetyan L.V., Redina E.A. Motivatsionnaya gotovnost’ psikhologov k okazaniyu ekstrennoi psikhologicheskoi pomoshchi postradavshim v chrezvychainykh situatsiyakh [Motivational readiness of psychologists to provide emergency psychological assistance to victims in emergency situations]. Mediko-biologicheskie i sotsial’no-psikhologicheskie problemy bezopasnosti v chrezvychainykh situatsiyakh [Medical-biological and socio-psychological problems of safety in emergency situations], 2021, no. 1, рр. 107—115. (In Russ.).

- Ryadinskaya E.N. Osobennosti adaptatsionnykh resursov mirnykh zhitelei, prozhivayushchikh v zone vooruzhennogo konflikta, v kontekste izucheniya transformatsii lichnosti [Features of adaptation resources of civilians living in the zone of armed conflict in the context of the study of personality transformations]. Klinicheskaya i spetsial’naya psikhologiya = Clinical and special psychology, 2017. Vol. 6, no. 4, рр. 105—124. (In Russ.).

- Shoigu Yu.S., Timofeeva L.N., Tolubaeva N.V. Osobennosti okazaniya ekstrennoi psikhologicheskoi pomoshchi pri perezhivanii utraty v chrezvychainykh situatsiyakh [Features of providing emergency psychological assistance in experiencing loss in emergency situations]. Natsional’nyi psikhologicheskii zhurnal [National Psychological Journal], 2021, no. 1(41), рр. 115—126. (In Russ.).

- Yul U., Uil’yams R.M. Strategiya vmeshatel’stva pri psikhicheskikh travmakh, voznikshikh vsledstvie masshtabnykh katastrof [Intervention strategy for mental injuries resulting from large-scale disasters]. Detskaya i podrostkovaya psikhoterapiya. Pod red. D.A. Leina, E. Millera. SPb.: Piter, 2001, рр. 275—308. (In Russ.).

- Cahil H. Strategies for supporting student and teacher wellbeing post-emergency. Six-monthly Journal on Learning, Research and Innovation in Education, 2020, no. 12(1).

- Hebert M., Langevin R., Oussaid E. Cumulative childhood trauma, emotion regulation, dissociation, and behavior problems in school-aged sexual abuse victims. Journal of Affective Disorders, 2018, no. 1, рр. 306—312.

- Nemiro A., Hijazi Z., O’connell R. Mental health and psychosocial wellbeing in education: The case to integrate core actions and interventions into learning environments. Intervention, 2022, no. 1, рр. 36—45.

- Sapadin K., Hollander B.L.G. Distinguishing the need for crisis mental health services among college students: Correction to Sapadin and Hollander. Psychological services, 2021, no. 2, рр. 317—326.

- Terr L.C. Childhood traumas: An outline and overview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 1991, no. 14(8), рр. 10—20.

- Xiao H., Carney D.M., Janis S.J. Are we in crisis? National mental health and treatment trends in college counseling centers. Psychological Services, 2017, no. 4, рр. 407—415.

Information About the Authors

Metrics

Views

Total: 1234

Previous month: 57

Current month: 68

Downloads

Total: 367

Previous month: 15

Current month: 10