My history with Alexander Romanovich Luria began in 1975, when I spent a year in Moscow for a postdoctoral study funded by IREX. I had been reading Luria’s work over the years of my PhD studies at the University of Chicago, but I had assumed it was unlikely that I would ever meet the globally distinguished academic. But Mike Cole, who had studied with Luria a few years prior, helped make it possible. In fact, during that year in Moscow, I found that Mike’s name opened many doors. So, in the fall semester of 1975 I turned up at a lecture that Luria was giving at the Faculty of Psychology at Moscow State University (MSU). At the end of the session, I walked up to him and told him I was a friend of Mike’s, and he greeted me warmly and said I should come to see him soon for a chat.

A week later, I went to see him at his apartment on Frunze Street. He started by asking me whether I would prefer to speak in Russian or in English, and I told him English. It was only later in the year that my Russian began to approximate his English, and it was only then that we switched increasingly to Russian. I told Luria that was in Moscow to continue my studies in psycholinguistics, and after discussing the ongoing research that he and others were doing, he suggested that I get in touch with Tanya Akhutina.

This was all part of my broader effort at the time to network with colleagues in Moscow, many of whom were destined to become important figures in international scholarly circles in the decades ahead. In Moscow, Tanya Akhutina, who was part of Luria’s research and clinical group, helped me delve both into my psycholinguistic studies and into neurolinguistics, a field that was only just then emerging and owed much to Luria’s leadership. Tanya’s hospitality and intellectual standing made it possible to meet other members of Luria’s group and others at the Institute of Linguistics, particularly those in A.A. Leont’ev’s group on communication and psycholinguistics. All of this opened a whole world of scholarship to me that few in the West even knew existed. The list of those I met in Moscow that year included figures such as A.V. Zaporozhets, V.P. Zinchenko, A.N. Leont’ev, D.B. El’konin, and V.V. Davydov, as well as younger figures such as A.G. Asmolov, V.I. Golod, and B.S. Kotik.

The time I spent with Luria left me with countless memories but here, I shall recount just couple of them that particularly stand out. The first occurred when Jerome Bruner visited Moscow in December 1975. Along with hundreds of others, I went to the Faculty of Psychology that day to hear his lecture. I arrived just as Luria and Jerry were walking down the hallway to the lecture room, and I overheard Jerry asking Luria who would be interpreting for him. The latter replied that he would do it himself. After the lecture hall became settled, Luria made his introductory remarks about Jerry and then turned the podium over to him.

What happened then was a demonstration of respect and admiration between two major figures in world scholarship, but it also had a humorous dimension. Jerry said about three sentences, and Alexander followed with three sentences in Russian. They followed this pattern for a few more turns, and then Jerry said three sentences, and Alexander Romanovich said five, which included what Jerry said plus some commentary. After another few minutes, Jerry was saying three sentences and Alexander Romanovich was saying 10, which included seven sentences of critical commentary. I don’t think Jerry ever got to the end of what he wanted to say, but it was a rare and memorable intellectual experience for the audience.

This was all done with great respect and gentleness on Luria’s part, but it left Jerry, always the enthusiastic speaker, without the chance to say as much as he wanted, and it also produced some puzzlement on his part since he did not know what was being said in Russian. In the years that followed, I met with Jerry on several occasions, and we revisited this story, which was a source of great amusement to both of us. But the bottom line for Jerry was his deep respect and admiration for Luria and his accomplishments, including his ground-breaking research on aphasia, neuropsychology, and cross-cultural psychology. But these accomplishments went even further than that, as in Luria’s tireless efforts to introduce the world to the ideas of Lev Vygotsky, who, he modestly insisted, inspired everything that he had ever done.

A second episode that left a deep impression on me came from Luria’s work as a clinician. At a time when scanning technology was barely imaginable, he coupled brilliant conceptual formulations with highly developed clinical techniques, borne out of long experience, in an effort to localize the site of brain trauma. He would carry out his assessments in a seemingly effortless way in clinical sessions, all the while providing a running commentary for the students in attendance. This often involved patients whose emotions could overcome them when they became frustrated and alarmed at not being able to perform a task that they had found so easy before their stroke or brain injury. During a clinical session I witnessed on March 15, 1976, I recorded in my notebook that a woman in her sixties who had suffered a stroke two months earlier broke down sobbing because she was so frustrated about her lack of progress. Without missing a beat, Luria reached over, grasped her hand, and provided some words of comfort before returning to the clinical seminar.

This episode was part of a clinical seminar about aphasia, primarily, but it was also a seminar about human compassion. Luria’s sympathetic words and gesture were genuine, and the woman clearly felt this. Not being a clinician myself, I do not know how common or successful such small interventions are, but watching Luria do this in his own professional and compassionate way was very moving. It was all part of the clinical lesson for the day.

This episode also deepened my appreciation for two of Alexander Romanovich’s books that will continue to be read long after the invention of scanning technology made it possible to pinpoint the exact site of brain injury. These are The Man with the Shattered World and The Mind of a Mnemonist: A Little Book about a Vast Memory. The latter was published in English with a foreword by Jerry Bruner, and both books were dubbed the first “neurological novels” by Oliver Sacks, who went on to produce many more works in this genre. These two slender volumes emphasize the need to study patients in all their complex humanity. Luria was far ahead of his time in formulating the idea that patients must be approached as whole human beings rather than simply vehicles of symptoms. This was reflected in his approach to the brain in terms of interacting functional systems and the assumption that specialized research focusing on narrow issues is unlikely to succeed if we don’t appreciate the larger issues involved in being human. For him, all this was simply part of being a decent, compassionate clinician.

For me, episodes such as these provided insight into Luria’s approach to life. It is especially striking that he managed to keep this humanity intact after living through so many challenges brought on by war and Soviet politics. In the end, he was one of the best models I have ever encountered for how to combine great intellect and compassion, and for that reason, he continues to serve as an inspiration today.

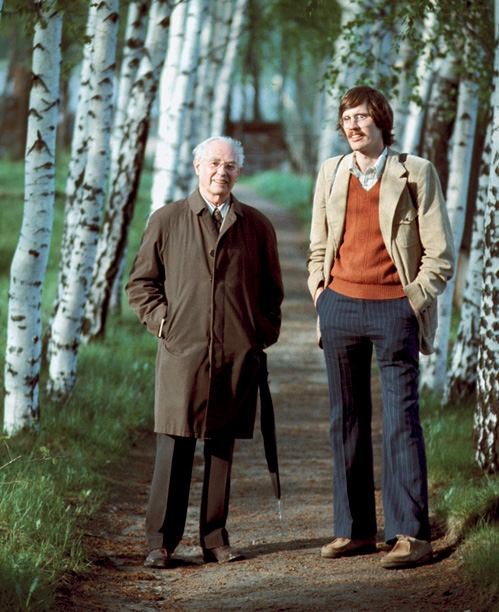

Fig. 1. A.R. Luria and J. Wertsch