Introduction

There has been an increase in scientific interest in spirituality in recent decades [Bratus’, 2019; Vorob’eva, 2019; Znakov, 2018; Ozhiganova, 2016; Emmons, 2004; MacDonald, 2000]. The problem of spirituality in publications crowds out the more traditional topic of religiosity, which reflects not only the change in “research fashion”, but also the ongoing socio-cultural changes associated with the spread of various forms of “non-traditional” spirituality. The concept of spirituality is broad enough to cover various forms of religious spirituality (including non-church, individual religiosity) and various manifestations of spiritual life that are not related with religious faith.

Russian psychodiagnostics lacks measures of spirituality. Among the measures used in Russian researches of spirituality it is necessary to note first of all the “Inspirit” questionnaire, which takes into account only religious spirituality [Gruzdev, 2006; Kass, 1991] and the recently elaborated Spiritual Personality Inventory [Ozhiganova, 2019]. The “Personality’s Hierarchy” questionnaire was elaborated in our country by E.V. Shestun et al. for identifying the spiritual level in the personality hierarchy, characterized by the authors through the priority of the realization of one’s destiny, spiritual growth and development [Shestun, 2010]. Other measures have not gained popularity due to theoretical or psychometric problems.

Given the abundance of articles devoted to a theoretical analysis of spirituality [5; 8; 15, etc.], we will consider here only the most important theoretical issues for measuring of spirituality. There is one opinion about the complex multi-component, multi-level structure of spirituality [Znakov, 2018; Ozhiganova, 2016; MacDonald, 2000], which means that attempts to measure spirituality using single-scale questionnaries are poorly justified. The variety of forms and manifestations of spirituality, the complexity of its structure explain the variety of approaches to measuring spirituality in psychology: in 2010, 24 measures of spirituality were considered in the review [Kapuscinski, 2010].

Among the main characteristics of spirituality, many researchers indicate the typical for spiritual people experience of closeness to the sacred, the sublime, which can be presented by various objects: the existence of God, God, the Spirit, the highest truth, humanity, etc. [Kapuscinski, 2010]. According to V.V. Znakov, “a person’s spiritual aspirations reflect one’s attempts to go beyond everyday life and touch other, deeper and at the same time sublime levels of human existence” [Znakov, 2018, P. 29-30].

Among other important characteristics of spirituality, there is its association with belief in the supernatural, and some researchers consider such beliefs to be one of the defining features of spirituality [Lindeman, 2012]. In the five-factor model of spirituality by D.A. MacDonald, belief in the supernatural constitutes a separate factor moderately associated with the factor of spiritual experience [MacDonald, 2000]. A well-known theoretical concept of the connection between spirituality and morality [Znakov, 2018; Ozhiganova, 2016] is confirmed only by rare empirical studies: for example, it has been shown that spiritual experiences mediate the relations between religiosity and moral feelings [Hardy, 2014].

Spirituality is considered as a sign of psychological well-being; however, research results show that different components of spirituality are associated with it in different ways: only one component of spirituality, which is referred to as existential well-being, shows a significant correlation [Migdal, 2013]. In the context of modern concepts of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being [Huta, 2016; Peterson, 2005], it seems reasonable to assume that spirituality should be associated with eudaimonic well-being, reflecting a person’s desire for a meaningful life aimed at realizing one’s own potential and purpose.

Since the measurement of spirituality requires an operational definition of this concept, based on the generally recognized characteristics discussed above, spirituality can be defined as a feeling of connection or unity with something sacred and the desire for achieving it [Davis, 2015]. Such a definition does not describe all aspects of spirituality, however, it marks one of the most important features that allow not only to distinguish the spiritual from the non-spiritual, but also to systematize the variety of forms of spiritual experience, depending on what exactly the subject considers as sacred.

Based on this understanding of spirituality, E. Worthington [Worthington, 2012] in his concept divides spirituality depending on the object that causes a feeling of connection, unity or closeness into four types: theistic (closeness to God), humanistic (closeness to humanity), naturalistic (closeness to nature) and transcendent spirituality (closeness to space, infinity, transcendence). Theistic spirituality includes the experience of closeness, connection, and unity with God, with a numen. Humanistic spirituality is characterized by the experience of connectedness and unity with other people or humanity as a whole. Naturalistic spirituality is characterized by the experience of closeness and unity with nature. Transcendent spirituality involves the experience of closeness, connectedness, and unity with something supernatural that transcends physical reality and cannot be expressed in words.

Based on this concept, D. Davis and coauthors [Davis, 2015] developed the Sources of Spirituality Scale (SOS scale), which measures the experiences associated with each of the above-mentioned objects. The authors added Self to the objects of spirituality as a source of experiences of the integrity of the Self, but later they excluded this scale due to its debatable justification [Westbrook, 2018]. In elaborated Russian-language version of the SOS scale we kept Self subscale, leaving the decision on its necessity to the users.

Method

The purpose of this study was to develop a Russian-language version of the Sources of Spirituality Scale (SOS-Ru). Based on the results of the early studies, the following assumptions have been put forward:

-

The Theistic subscale is closely related to religious spirituality.

-

The Human subscale is closely related to global social identification.

-

The Nature subscale correlates with a sense of connection with nature.

-

The Transcendent subscale is closely related to belief in supernatural phenomena.

-

All subscales of the SOS-Ru are related to morality, eudaimonic orientation and subjective well-being.

-

The latent profiles on the subscales allow describing different types of spirituality.

The total sample of 412 participants was composed of two groups. The first group, which took part in a paper-pencil survey, included 250 full-time and part-time students of two universities in Biysk (68% women, mean age M = 24.04, SD = 7.93). This group answered the questions from all of the measures listed below, with the exception of the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (BIDR). The second group of 162 participants (74% women, mean age M = 31.06, SD = 10.51) completed an online survey that included SOS-Ru and the BIDR.

Measures. The Sources of Spirituality Scale (SOS scale) by D. Davis et al. [Davis, 2015] consists of 18 items describing various spiritual experiences associated with a different source: Theistic, Transcendent, Human, Nature, and Self. Two psychologists made a translation of the text into Russian (see Appendix), which was then discussed and refined with the participation of three experts involved in various philosophical and psychological studies of spirituality.

During the validation, a set of questionnaires was used to measure various manifestations of spirituality and psychological constructs close to it.

Index of core spiritual experiences (INSPIRIT) by J. Kass et al. [Gruzdev, 2006; Kass, 1991], which measures religious spirituality.

A Revised Paranormal Belief Scale by J. Tobacyk in the Russian adaptation (D.S. Grigoriev [Grigor’ev, 2015]), which includes seven subscales: Traditional religious belief, Psi-abilities, Witchcraft, Superstition, Spiritualism, Extraordinary Life Forms and Precognition.

The Global Social Identification Scale (GSI) by G. Reese in the Russian adaptation (T.A. Nestik [Nestik, 2018]) to measure the disposition of a person to identify with humanity.

Connectedness to Nature Subscale by F.S. Mayer and C.M. Frantz in the Russian adaptation by K.A. Chistopolskaya et al. [Chistopol’skaya, 2017].

The Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ) by J. Graham et al. in the Russian adaptation by O.A. Sychev, I.N. Protasova and K.I. Belousov [Sychev, 2018]. The questionnaire includes five scales: Care, Fairness, Loyalty, Authority and Purity. The first two scales refer to individualizing moral foundations, and the last three scales constitute binding moral foundations.

Russian version of Orientations to Happiness questionnaire (OH), developed by O.A. Sychev and I.V. Anoshkin [Sychev, 2019] based on the Orientations to Happiness measure by C. Peterson et al. [Peterson, 2005].

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) by E. Diener in Russian adaptation by E.N. Osin and D.A. Leontiev [Osin, 2008].

To assess the social-desirability bias the Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding (BIDR) questionnaire by D. Paulhus in Russian adaptation by E.N. Osin was used [Osin, 2011].

Results

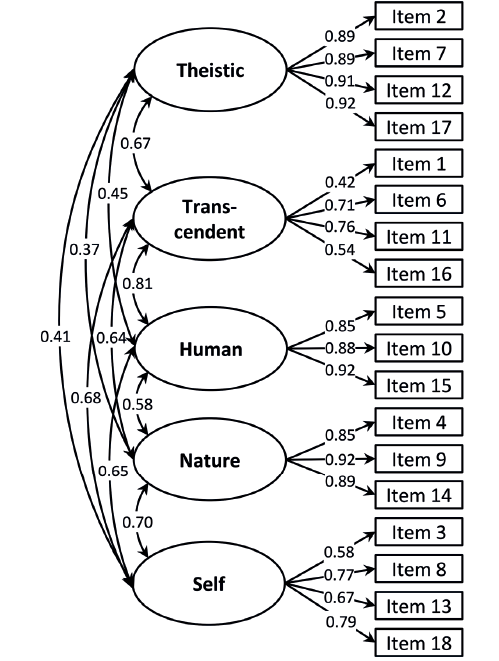

In order to test the five-factor structure of the SOS-Ru scale, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using the robust maximum likelihood (MLR) algorithm. During the CFA each item was considered as an indicator of the latent factor relevant to the subscale, all factors were allowed to correlate with each other. The results showed a good fit of the five-factor model (Fig. 1) to the data: χ2 = 260.16; df = 125; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.962; TLI = 0.953; RMSEA = 0.051; N = 412.

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics, Intercorrelations, and Reliability on SOS-Ru subscales (N = 412)

|

Subscales |

Theistic |

Transcendent |

Human |

Nature |

Self |

|

Theistic |

— |

||||

|

Transcendent |

0.55* |

— |

|||

|

Human |

0.48* |

0.35* |

— |

||

|

Nature |

0.52* |

0.34* |

0.61* |

— |

|

|

Self |

0.62* |

0.41* |

0.55* |

0.53* |

— |

|

Means |

2.85 |

2.94 |

3.44 |

3.35 |

2.74 |

|

SD |

0.90 |

1.17 |

0.79 |

1.05 |

1.03 |

|

Reliability (Cronbach’s α) |

0.73 |

0.95 |

0.79 |

0.92 |

0.92 |

Notes. Significance: * — p < 0.001.

Fig. 1. Factor model of the SOS-Ru scale (all coefficients are significant at p < 0.01)

Table 2

Correlations of SOS-Ru Subscales with External Validity Criteria (N = 250)

|

Measures |

Subscales |

||||

|

Theistic |

Trans-cendent |

Human |

Nature |

Self |

|

|

INSPIRIT, Religious spirituality |

0.80*** |

0.47*** |

0.25*** |

0.23*** |

0.19** |

|

OH, Eudemonic orientation |

0.32*** |

0.36*** |

0.46*** |

0.43*** |

0.41*** |

|

OH, Hedonic orientation |

0.00 |

0.12 |

0.15* |

0.14* |

0.24*** |

|

GSI, Global social identification |

0.32*** |

0.44*** |

0.63*** |

0.40*** |

0.44*** |

|

Connectedness to Nature |

0.32*** |

0.48*** |

0.47*** |

0.58*** |

0.45*** |

|

MFQ, Care |

0.20** |

0.27*** |

0.25*** |

0.38*** |

0.34*** |

|

MFQ, Fairness |

0.10 |

0.15* |

0.15* |

0.30*** |

0.33*** |

|

MFQ, Loyalty |

0.38*** |

0.23*** |

0.27*** |

0.32*** |

0.28*** |

|

MFQ, Authority |

0.49*** |

0.28*** |

0.28*** |

0.24*** |

0.25*** |

|

MFQ, Purity |

0.38*** |

0.32*** |

0.30*** |

0.37*** |

0.33*** |

|

MFQ, Individualizing moral foundations |

0.16* |

0.22*** |

0.21*** |

0.36*** |

0.35*** |

|

MFQ, Binding moral foundations |

0.47*** |

0.31*** |

0.32*** |

0.35*** |

0.32*** |

|

PBS, Traditional religious belief |

0.70*** |

0.45*** |

0.22*** |

0.21*** |

0.16* |

|

PBS, Psi-abilities |

0.37*** |

0.33*** |

0.14* |

0.07 |

0.02 |

|

PBS, Witchcraft |

0.40*** |

0.39*** |

0.16* |

0.17** |

0.05 |

|

PBS, Superstition |

0.29*** |

0.26*** |

0.13* |

0.05 |

-0.02 |

|

PBS, Spiritualism |

0.42*** |

0.44*** |

0.16** |

0.18** |

0.05 |

|

PBS, Extraordinary Life Forms |

0.17** |

0.32*** |

0.10 |

0.08 |

0.04 |

|

PBS, Precognition |

0.42*** |

0.36*** |

0.18** |

0.22*** |

0.07 |

|

SWLS, Satisfaction with life |

0.18** |

0.10 |

0.23*** |

0.13* |

0.31*** |

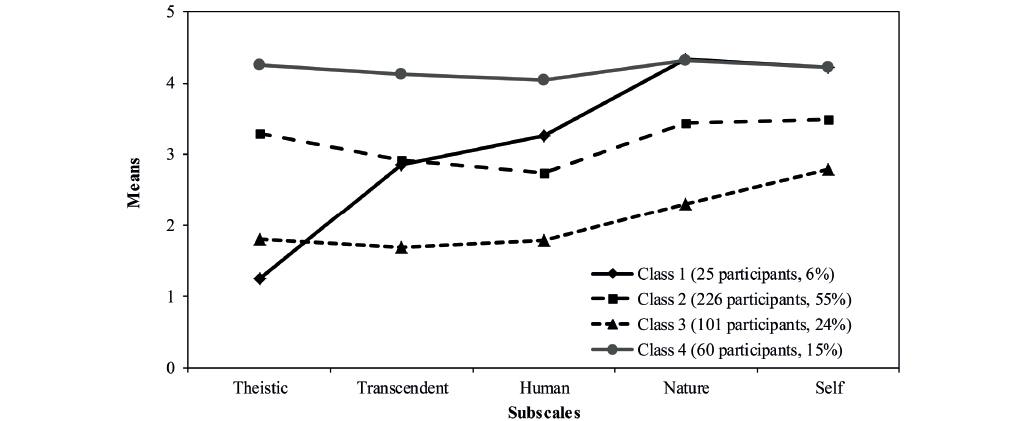

Fig. 2. The results of the analysis of latent profiles on the SOS-Ru subscales

Table 3

Gender Differences on the SOS-Ru Subscales

|

Subscales |

Means |

SD |

Cohen’s d |

U |

Z |

p |

||

|

W |

M |

W |

M |

|||||

|

Theistic |

3.04 |

2.70 |

1.12 |

1.23 |

0.29 |

14473.5 |

2.57 |

0.010 |

|

Transcendent |

2.86 |

2.64 |

0.92 |

1.06 |

0.22 |

15217 |

1.88 |

0.060 |

|

Human |

2.77 |

2.65 |

0.96 |

1.15 |

0.12 |

16329.5 |

0.99 |

0.322 |

|

Nature |

3.46 |

3.12 |

0.98 |

1.16 |

0.33 |

14426.5 |

2.75 |

0.006 |

|

Self |

3.44 |

3.48 |

0.77 |

0.83 |

—0.05 |

16795 |

—0.56 |

0.578 |

Note: W = women, M = men, the sample size N is in parentheses, SD = standard deviations, U = Mann-Whitney U-test, Z = Z-statistic for the U-test, p = statistical significance.

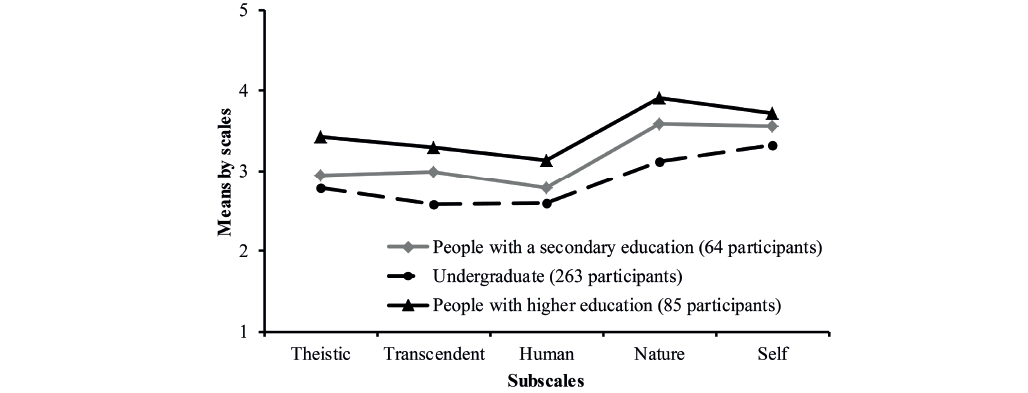

Fig. 3. Means by the SOS-Ru subscales in different age groups

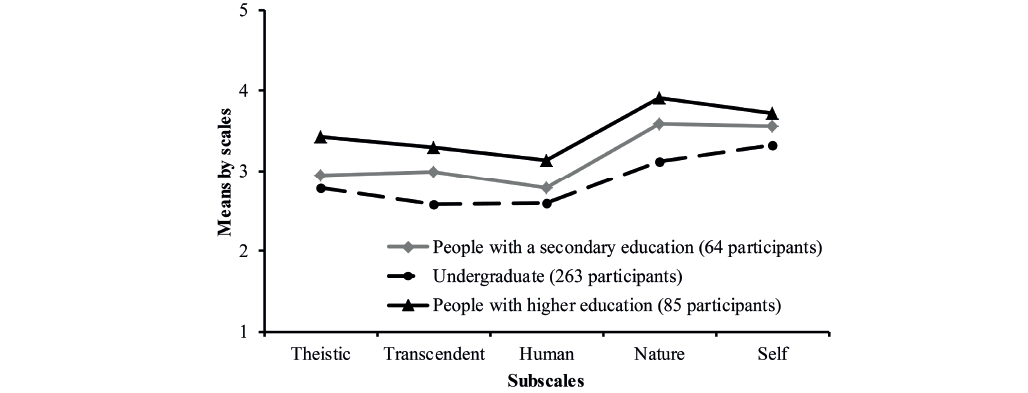

Fig. 4. Means by the SOS-Ru subscales in groups with different levels of education

Descriptive statistics on the subscales (Table 1) indicates that the mean values are close to the center of the five-point scale, and the standard deviation is close to one. All subscales moderately and significantly correlate with each other.

To analyze the validity of the questionnaire, the correlation coefficients of the SOS-Ru subscales with other measures were calculated (Table 2). Convergent validity of the Theistic subscale is supported by its high correlation with religious spirituality and traditional religious belief. The construct validity of this subscale is confirmed by correlations with binding moral foundations measuring adherence to conservative moral values.

The construct validity of the Transcendent subscale is confirmed by correlations with such indicators as religious spirituality and traditional religious belief, global social identification, connectedness to nature, belief in spiritualism, witchcraft and precognition. The convergent validity of the Human subscale is confirmed by the fact that it shows the highest correlation with global social identification. Its construct validity is supported by its association with eudaimonic orientation.

The convergent validity of the Nature subscale is confirmed by the fact that it showed the highest correlation with the connectedness to nature. Correlations of this subscale with global social identification, eudaimonic orientation, moral foundations (care and purity) were also revealed. The construct validity of the Self subscale is supported by correlations with eudaimonic orientation and subjective well-being.

Spiritual experiences (except on the Transcendent subscale) showed a positive correlation with subjective well-being. Relations of spiritual experiences with moral foundations are revealed: the subscales of Nature and Self show the highest correlations with individualizing moral foundations, while the Theistic subscale most closely correlates with binding moral foundations. The Theistic and Transcendent subscales show significant correlations with the traditional religious belief scale and many other scales of belief in the paranormal. The Human, Nature, and Self subscales show only some moderate correlations with belief in the paranormal, while the correlations with traditional religiosity, although significant, are rather small in magnitude.

Only one of the five SOS-Ru subscales (Self) showed a weak but statistically significant association with a social-desirability bias (r = 0.17; p < 0.05). Weak and marginally significant (p < 0.10) correlations with social-desirability bias were obtained for the Nature and Human subscales (r = 0.15 for each).

To test the hypothesis about the possibility of distinguishing different types of spirituality using the subscales of the questionnaire, we implemented Latent Class Analysis with the number of latent classes from two to seven. Based on the entropy value (0.86) and the maximum decrease in the Bayesian information criterion value a solution with four classes was chosen. The results of the analysis (see fig. 2) indicate the presence of one “secular” type of spirituality (class 1) and three “harmonious” types, combining both a religious (mystical) and secular component at a low, moderate or high level (classes 2, 3 and 4).

The analysis of the distribution on the SOS-Ru subscales indicates a significant deviation from normality: the values of the Shapiro-Wilk test are from 0.970 to 0.986 (p < 0.01), however, the asymmetry coefficients are small (from —0.35 to 0.16 for different subscales). Spiritual experiences, expressed in a sense of connection with God and nature, turned out to be more typical for women (Table 3).

To analyze age differences on the SOS-Ru subscales the hypothesis of homogeneity of median values in different age groups was tested using the Kruskal-Wallis test. A statistically significant effect of age was found on the following subscales: Theistic (χ²(4) = 50.33; p < 0.001), Transcendent (χ²(4) = 23.02; p < 0.001), Human (χ²(4) = 18.12; p < 0.01) and Nature (χ²(4) = 27.69; p < 0.001).

Presented in fig. 3 means illustrate the trend towards the growth of spiritual experiences in adulthood, and this trend is most pronounced on the Theistic and Transcendent subscales. Groups with different levels of education also show statistically significant differences across all subscales (Fig. 4) according to the Kruskal-Wallis test (at p < 0.01).

The most different groups on the subscales of the questionnaire (undergraduate and people with higher education) differ significantly from each other in age. Covariance analysis with control of age showed that for the Theistic subscale only the impact of age remains statistically significant, for the Self subscale the impact of the level of education is significant, and both age and education are significant factors for the other subscales.

Discussion

The results of the study indicate that the Russian-language version of the SOS scale has high reliability of its subscales, and the five-factor structure fits well to the data. The convergent validity of the Theistic, Human, and Nature subscales is confirmed by high correlations with scales that measure similar psychological constructs. For the Transcendent and Self subscales construct validity was tested and it was confirmed by the expected correlations with other psychological constructs that should be associated with the relevant aspects of spirituality. The Transcendent subscale showed close correlations with belief in supernatural phenomena, which is one of the components of spirituality [MacDonald, 2000]. The close correlation of the Self subscale with subjective well-being confirms the important contribution of the experience of the unity and integrity of the Self to one’s well-being.

During testing of the construct validity of the subscales, the notion of the interrelations between spirituality and morality, widespread in theoretical works, but poorly studied, was confirmed [Znakov, 2018; Ozhiganova, 2016]. It should be noted that binding moral foundations showed the greatest correlation with religious spirituality (measured by the Theistic subscale), while individualizing moral foundations are most strongly associated with subscales describing a rather secular type of spirituality (Nature and Self), which fits well with the ideas of the moral foundation’s theory [Graham, 2010]. Despite the positive public assessment of spirituality, the impact of the social-desirability bias on the results in an anonymous survey was insignificant for most subscales.

The profiles of spirituality identified in this study were not identical to those found by the authors of the original English-language version [Davis, 2015]; in particular, a profile with an apparent priority of religious spirituality was not revealed in our study. This may be a consequence of either the insufficient representativeness of the sample, which might not include deeply religious people, or the rarity of this form of spirituality in the Russian population.

Conclusion

Measuring of spiritual experiences taking into account their sources allows obtaining a relatively differentiated and valuable description of the person’s spiritual sphere regardless of religiosity. The proposed Russian-language version of the SOS scale, which has excellent psychometric characteristics, makes it possible to explore the various manifestations of spirituality, taking into account a variety of spiritual experiences.

Appendix

Russian-language version of Sources of Spirituality Scale

Пожалуйста, укажите степень Вашего согласия с приведенными утверждениями. Варианты ответа: 1 — совершенно не согласен; 2 — не согласен; 3 — ни да, ни нет; 4 — согласен; 5 — полностью согласен.

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

|

1. У меня было ощущение чего-то бесконечного |

|||||

|

2. Я чувствовал, что Бог рядом |

|||||

|

3. Я чувствовал себя полностью верным себе |

|||||

|

4. Я чувствовал единство с природой |

|||||

|

5. Я чувствовал свою связь со всем человечеством |

|||||

|

6. Я чувствовал свою связь с невыразимой силой бытия |

|||||

|

7. Я чувствовал свою близость к Богу |

|||||

|

8. У меня было ощущение единства своего внутреннего мира |

|||||

|

9. Я ощущал свою связь с природой |

|||||

|

10. Я ощущал свою близость ко всему человечеству |

|||||

|

11. Я чувствовал единство с чем-то, что не могу описать словами |

|||||

|

12. Я знал, что Бог со мной |

|||||

|

13. Я чувствовал себя соответствующим своей сущности |

|||||

|

14. Я ощущал свою близость к природе |

|||||

|

15. Я ощущал единство со всем человечеством |

|||||

|

16. Я чувствовал присутствие чего-то из другого мира или измерения |

|||||

|

17. Я чувствовал присутствие Бога |

|||||

|

18. У меня было чувство своей целостности |