BACKGROUND

It's not without reason that the idea of establishing territorial psychiatric hospitals appeared in Russia. By the time of its emergence, there had already been a fairly rooted culture of care for the mentally ill around the second half of the 19th century. The year 1762 can be taken as grand zero, when Emperor Peter III of Russia responded to the proposal of the Senate to send the mentally ill Kozlovsky princes to a monastery with the following order: “Send insane folks not to monasteries, but rather build a purposeful house for that, as is the custom in foreign countries, where lunatic asylums are established” [1]. In 1775, a decree was issued whereby the Welfare boards (Prikazy) were ordered to arrange asylums for the insane in each governorate. These were seen primarily as places of isolation — rather than treatment — of patients. Nevertheless, the decree emphasized that the patients should be treated “humanely”, and that the warden be “kind-hearted and gentle” [1]. Since then, the number of asylums for the mentally unstable has steadily increased. For example, in 1810 there were 14 specialized institutions in the Russian Empire, whereas by 1860 their number had grown to 43, of which 34 were independent and 9, departments at governorate hospitals. As the Russian psychiatrist Rote A.I. noted: “This step brought invaluable benefits, but still it was only the first practical attempt, these were lunatic asylums actually established by the state, which, however, did not yet constitute houses of care, much less for the treatment of mentally ill persons” [2]. The main challenge was finding enough qualified personnel: there were few specialists in Russia, doctors visited patients in such facilities only on certain days, and the mentally ill were supervised by personnel without appropriate training (most commonly, retired soldiers worked in lunatic asylums).

In 1842, the Ministry of Internal Affairs initiated an inspection of governorate asylums for the mentally ills. Based on the ensuing reports, it became obvious that the then-existing asylums for the mentally ills could not cope with the flow of patients and were not set up in the best way possible. Two years later, a special committee was set up under the Ministry of Internal Affairs that included government officials and doctors. The Committee held as follows: seeing that it was economically unprofitable to maintain facilities for the mentally ills in each separate governorate, and that it was practically impossible to staff each facility with qualified personnel, instead, one large institution ad to built to serve several governorates [1]. While December 30, 1844, can be considered the birthday of the project of territorial psychiatric hospitals, it took another 18 years for subsequent revision and approvals. The project was supported by governorate authorities, but after each detailed review, it often became clear that the real costs of building the hospitals would be much higher than the amount initially budgeted. In 1856, a commission convened to revise the project. The outcome of its activities was an updated project: it involved the construction of a number of central institutions, and “as an experiment” it was recommended to start with the construction of a hospital in Kazan [1]. It should be noted that out of the 8 hospitals provisioned by the project, only 7 were built and that virtually no information has been uncovered about the very last hospital, built in Grodno.

KAZAN, THE PLACE WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

In the spring of 1861, the design of the Kazan territorial asylum for the insane was approved by Emperor Alexander II [2]. The choice of the location was driven by the fact that the Welfare boards in the Kazan governorate had the funds needed to build the hospital, and that there was a University in Kazan which could train future medical personnel. At Kazan University, the teaching of psychiatry, albeit in all but theory, began in 1866, a year before psychiatry became a compulsory medical course in all higher educational institutions of the Russian Empire. This shows that the medical community felt the need to build up psychiatric knowledge and train the relevant professionals. The Kazan hospital opened in 1869. However, the experience of its operation in the first years turned out to be so controversial that it put into risk the very implementation of the remaining stages of the project.

The first territorial hospital for the insane in Russia was built on a project by the architect Zhukovsky P.T. Professor Balinsky Ivan Mikhailovich, who can arguably be referred to as the inspiration behind psychiatric facility construction in Russia, took the most active part in the effort, as he designed quite a number of mental health hospitals, as did doctor of medicine Frese Aleksandr Ustinovich, who became the first director of the facility. Frese A.U. stood at the origins of psychiatric science in Russia and, to boot, had the necessary experience: in 1862 he traveled to Europe to study the construction and operation of European psychiatric hospitals. The territory hospital was purpose-built for the accommodation of mentally ill patients, and was strikingly different from the governorate and local (zemstvo) asylums for the insane. Here is a 1879 report on the state of affairs in a zemstvo asylum in Kazan: “If the status of a person who went insane is difficult in general, then it must be unbearable in such a building as a zemstvo asylum for the insane. The aged, badly ventilated building with dark narrow corridors, and low ceiling and damp individual cells affected the mood”. And here is the report of the Poltava zemstvo (local administration) commission: “Wardens treat patients like a herd of animals, rule by the power of the fist; and howls are often heard in the house: 'Give me something to eat!'” [3]. The Kazan territorial hospital, built outside the city limits combining three spacious buildings and surrounded by extensive gardens, represented a striking contrast compared with such facilities (Figure 1). The multiple-buildings system made it possible to segregate patients by gender, by the nature of their condition, and even by social status, as it boasted first- and second-class blocks. Broad expanses lined with turf adjoined the blocks for restless patients, “to give some fresh air to patients who, by dint of their state of anxiety, cannot take walks in the gardens” [4]. Each department was equipped with canteens, buffets, a cloakroom, a water closet and a warden's room. For entertainment and leisure, a carpentry workbench, a lathe, billiards, checkers, books, and even a piano were available.

Figure 1. The Territorial hospital for the mentally ill in Kazan.

Restrain and other measures of physical coercion on patients were strictly prohibited at the hospital: violent patients were not tied up, but rather placed in special rooms with walls upholstered with soft material to avoid self-inflicted harm [5]. The Kazan hospital had steam heating, artificial ventilation and a water supply line. Frese A.U. brilliantly hence set forth the basic principle of the organization of his institution: “A lunatic asylum is not a prison, nor is an insane a criminal. The task of the lunatic asylum is to convince the patient of the truth of this situation by creating an objective environment” [6]. Moreover, a comfortable environment, good nutrition, outdoor walks, variety of leisure activities, according to Dr. Frese, were “important aids to the successful treatment of insanity”. The condition of patients was monitored by the director-physician, four residents, two male paramedics, and two female paramedics. The wardens and their pair of assistants kept order in the men's and women's quarters. Doctors and employees actually resided at the hospital and, thus, patients received “continuous and comprehensive care" [6].

Yet, the Kazan territorial hospital all but jeopardized the entire project of the construction of territorial hospitals. The matter was that Frese A.U. was of the opinion that his institution was meant primarily for the mentally ill with a chance at recovery. For incurable patients he allotted only a tenth of the total number of beds. Assessing the operation of his hospital from 1869 to 1879, Dr. Aleksandr Frese noted that 30% of the patients admitted were discharged after having fully recovered. The chances of recovery were especially high for those admitted to the hospital for the first time, provided that the duration of their condition at that point in time did not exceed six months. If after a year in the hospital there was no improvement, the patients were transferred to zemstvo asylums for the insane or returned to the care of relatives [4]. This approach resulted in many unoccupied beds in the hospital. Even though the Kazan territorial hospital had been envisioned to serve the seven nearest governorates, in reality it admitted patients from all over the empire. However, Frese A.U. throughout his life remained convinced that it was more economically sound for the state to cure a mentally disturbed person and return him/her to his/her everyday life, and, therefore, to active life, than to spend resources on care for incurable patients. He considered that the unoccupied beds in his hospital were due to a lack of public awareness about its operation and the conditions of the custody of patients [6]. Dr. Frese even published a pamphlet describing his institution and toured neighboring governorates in search of patients who fit the criterion of curability. This state of affairs continued until his death in 1884.

Ragozin Lev Fedorovich, who was not only an outstanding Russian psychiatrist, but also a gifted administrator, was appointed as the next director of the hospital. He took over the leadership of the institution at a very challenging time for the institution. Here is how professor Ostankov A.P. described the state of things: “The experience of the Kazan district hospital in the opinion of the ministry was considered so unsuccessful that even petitions initiated by the zemstvo requesting the construction of territorial hospitals were unsuccessful; the topic of central hospitals could at the time have been regarded as doomed had it not been for the energetic and fruitful activity of Ragozin L.F. and if further existence of the Kazan territorial hospital under his leadership had not radically changed the views of the government about territorial hospitals” [7]. Lev Ragozin, with the help of Ostovsky A.Ye., an engineer, expanded and partially rebuilt the hospital, introduced a boarding house system, which led to more money flowing into the coffers, which allowed him to, finally, take in all the patients of the zemstvo asylum for the insane, the zemstvo asylum was closed thereafter. Thus, Ragozin L.F. improved the living conditions of chronic patients and, at the same time, reduced costs for their care. But, most importantly, he regained the government's confidence in the project of territorial hospitals.

In 1888, Lev Ragozin assumed the post of director of the Medical Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and, with his most active participation, six more territorial psychiatric hospitals were built, as had been provided for by the project of 1856, in cities such as Warsaw, Vinnitsa, Vilna (later Vilnius), Tomsk, Moscow, and Grodno [3]. Thus, the geographical spread of the project covered areas ranging from the western borders of the Russian Empire to Siberia.

AT THE TURN OF THE CENTURIES

In 1891, the Warsaw territorial psychiatric hospital opened its doors in Tworky (later the territory of Poland). Obviously, by the time of its planning and establishment, the inertia of the past was still a reality: the hospital was built according to the pavilion system, which was considered as the best for sorting patients into groups, since Ragozin L.F. and colleagues had failed to prove that the hull model of hospital-building was much more practical and economical than the pavilion type. The largest amount of space was allotted to patients with hope of recovery, but the hospital also accepted incurable patients, persons sentenced to remain under medical supervision by the state, and people whose mental abilities were in doubt and needed to be tested [8]. In all other respects, the management of the Warsaw hospital was based on the principles tested at the Kazan territorial hospital: a picturesque countryside; doctors, paramedics, and caretakers living on the premises; and a ban on physical methods of restraint [8]. Able-bodied patients were recruited to work in the fields or in workshops, which was beneficial both for their condition and for replenishing the medical benefits fund. The hospital accepted patients from all ten governorates of the Kingdom of Poland and, as contemporaries noted, remained overcrowded even after its expansion in 1895.

For the care of the mentally ill patients in the southwestern region of the Russian Empire in 1896, a territorial psychiatric hospital was built about six kilometers from Vinnitsa (in Western Ukraine). The project was created with the active participation of Ragozin L.F. and Ostovsky A.Ye., who had been previously involved in the expansion of the Kazan hospital. Later on, work on the project was continued by civil engineer Krivtsov Ya.V. [1]. It was he who took the idea of building territorial hospitals to its logical conclusion, as he later became involved in the construction of the Vilna, Moscow, and Tomsk hospitals, making the necessary changes and improving the approach to construction.

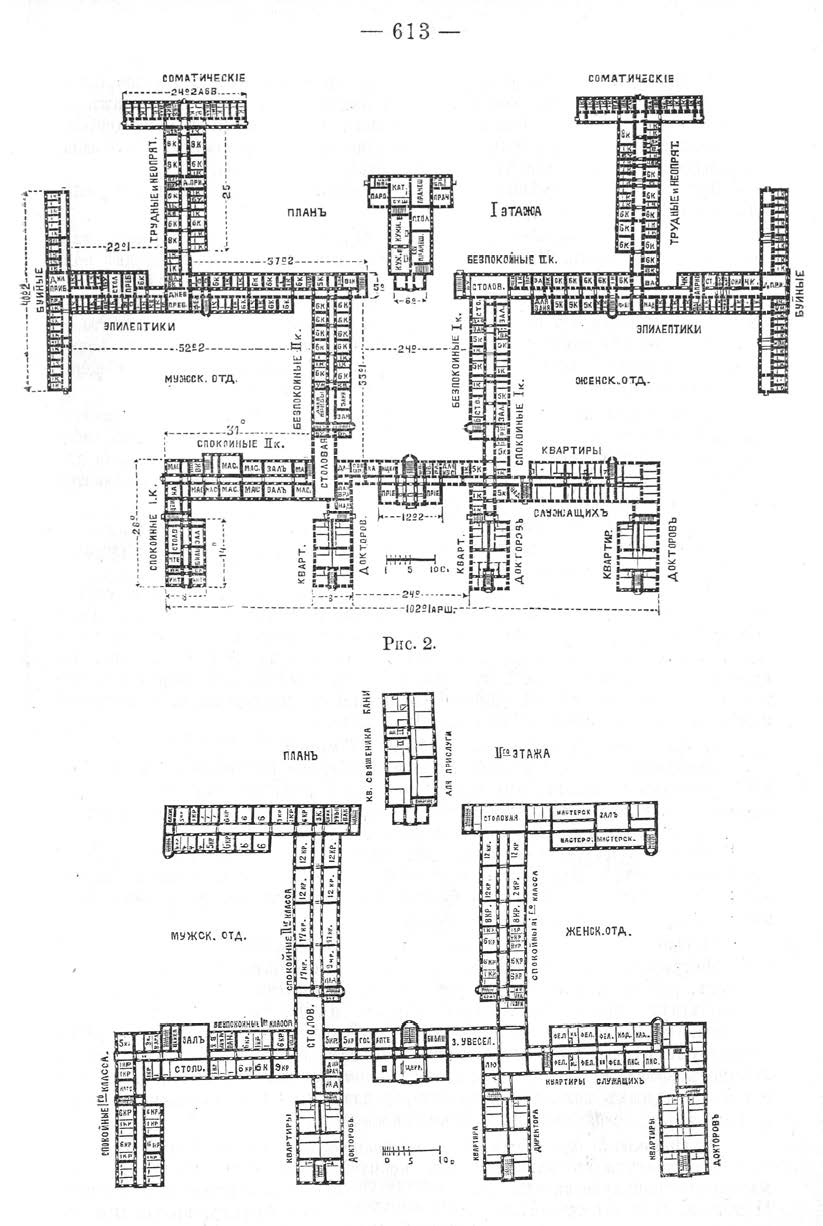

Looking back, it is remarkable that, from an architectural point of view, the Vinnitsa hospital marks the transition from a pavilion-style hospital to a hull model. As was noted by Professor Ostankov P.A., the pavilions of the Vinnitsa hospital “directly open into one another without intermediate corridors and warm galleries” [9]. This suggests that, through trial and error, Russian psychiatry arrived at an ideal solution: patients were fanned out to different departments and did not mix with one another. However, all departments remained under the same roof. Owing to such a topology, it became easier to keep an eye on the movements and occupations of patients and to make the rounds. In addition, heating and providing water to one large building proved cheaper than arranging for similar amenities in several, separate pavilions (Figure 2). In terms of amenities, the hospital was even ahead of its time: for instance, it had its own power plant, whereas a municipal power plant was built in Vinnitsa only in 1911. The construction of the territorial psychiatric hospital even influenced the infrastructure of the district: a highway was laid and paved from Vinnitsa to the hospital. The Vinnitsa hospital served the Kyiv, Volyn, and Podolsk governorates.

Figure 2. The project of the Vinnitsa territorial hospital.

In 1903, the grand opening of the Vilna (in Lithuania) territorial psychiatric hospital took place. At the time, it was the largest psychiatric hospital in the Russian Empire, designed for a capacity of one thousand beds. Two hundred patients were treated at the expense of the state, while the remainder of the bed space was fee-based so that maintenance of the hospital could pay for itself. All the principles of arranging for territorial hospitals were strictly followed here: constraint and isolation of patients was limited, compliant patients were allowed to venture even outside the territory, while games and concerts were organized at the hospital. A huge park and vegetable gardens adjoined the building, work in which was used as one of the options for occupational therapy for patients (Figure 3). It must be said that the first director of the Vilna hospital, Krainsky Nikolai Vasilievich, not only reasonably managed the hospital, but also actively championed the idea of large-scale psychiatric institutions. Speaking at the IX Pirogov Congress in 1904, he said the following: “Large-scale psychiatric hospitals in scientific and organizational terms have a significant advantage over small ones, better conditions for sorting various groups of patients: it is easier to find the benefits necessary for scientific psychiatry in them, and it is easy to achieve mutual exchange of opinions and information” [10].

Figure 3. Vilna territorial hospital.

TO SIBERIA

In the first decade of the 20th century, there was much concern over the issue of care of the mentally ill not only in the European part of the Russian Empire, but also in Siberia. For instance, the note by a medical inspector addressed to the Tomsk governorate administration stated that in the psychiatric department of one of the hospitals designed for a sixty-bed capacity, there were one hundred and twenty patients, because of which “we are compelled to deny assistance to a mass of people in need of treatment”1. The inspector concluded his message with a request “not to refuse a message about the time of the opening of the Tomsk territorial psychiatric hospital”. The relevance of the project was also illustrated by the fact that the City Duma (Council) allowed the Construction Committee to use any building materials located within the municipal boundary free of charge and promised to build an access road from the city to the hospital at its expense.

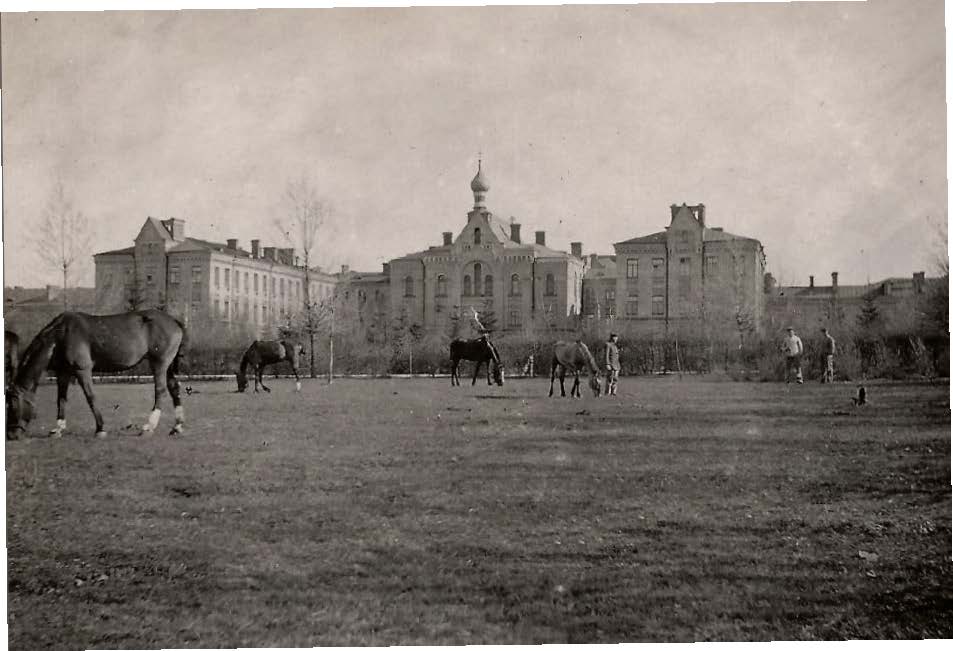

The point was not only that vast Siberia was in need of an institution for the isolation and treatment of people who, due to the state of their mind, could not live in society. At that time, Siberia was also a place of exile for criminals, among whom there was a considerable percentage of people with mental disorders. In that context, the purpose of the psychiatric hospital was broadened, which included housing of the mentally ill who had committed crimes, assessment of the mental abilities of persons in respect to whom the court was in two minds, imprisonment of mentally ill prisoners and isolation of incurable patients and patients deemed to be a danger to the public. Given all these categories, the Tomsk hospital became one of the largest in the Russian Empire; it accommodated 1,050 patients2 (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Front view of the Tomsk territorial hospital.

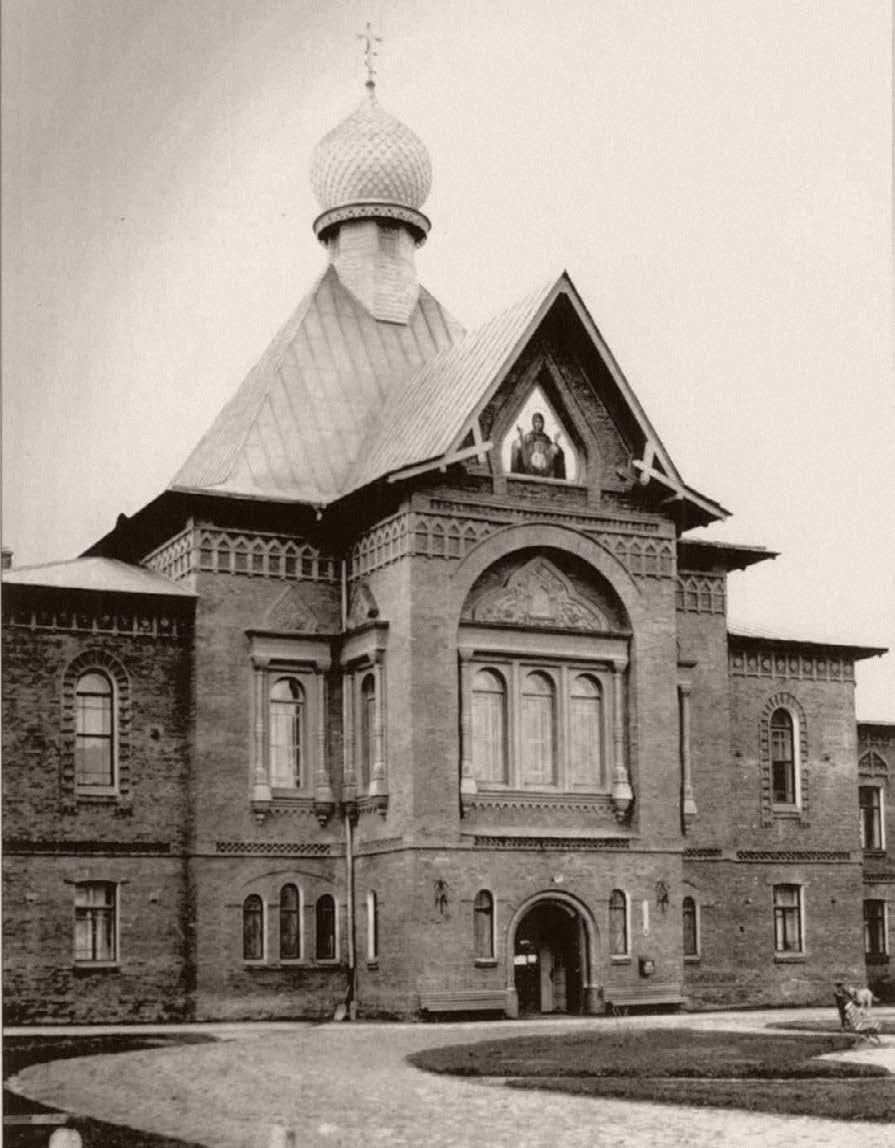

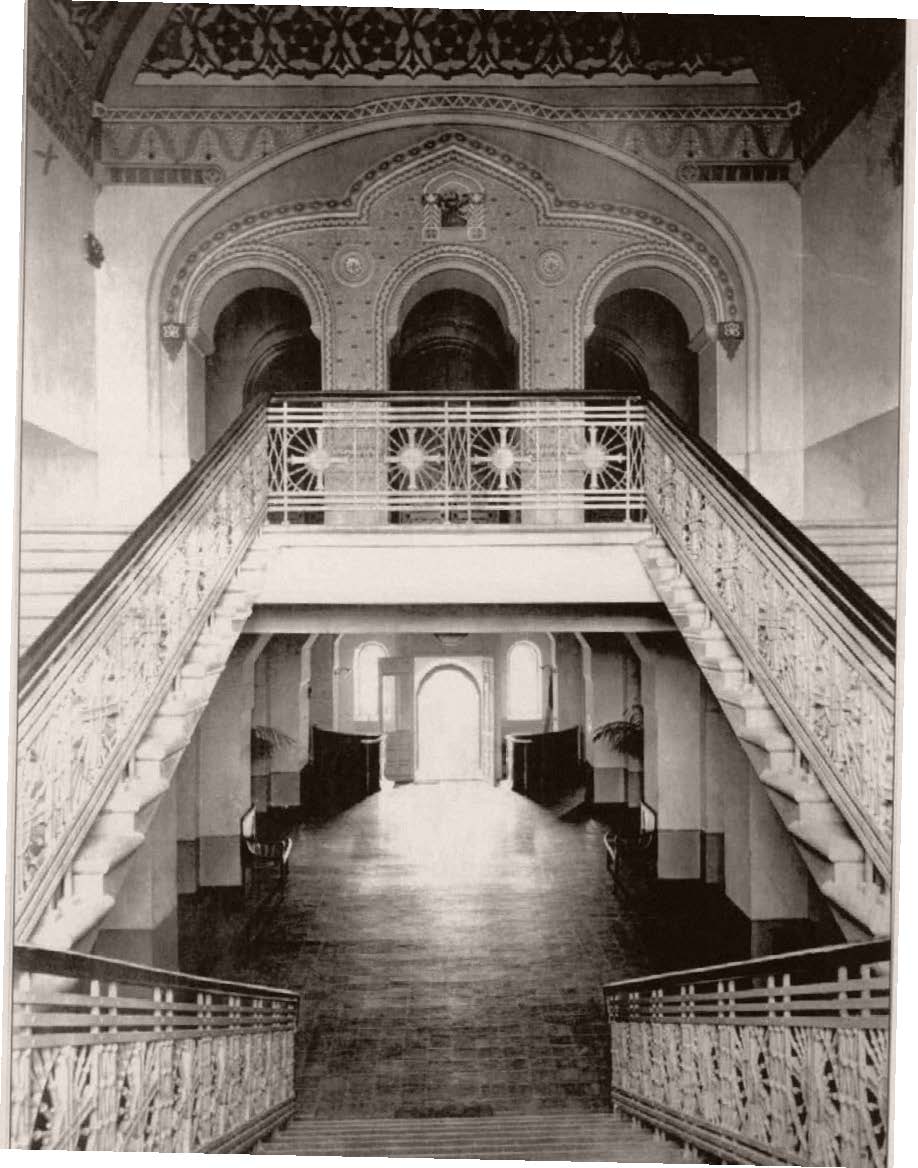

The hospital in Tomsk was built according to the same layout as the Vinnitsa and Moscow hospitals. By that time, “psychiatric facility construction” had accumulated some experience in the operation of buildings, so that the chief engineer of the project, Krivtsov Ya.V., could correct the shortcomings: for instance, too-long corridors were recognized as a drawback of the Vinnitsa hospital, and they were eschewed in the layout of the Tomsk hospital. Basically, the new clinic repeated the principles of rationality and harmony tested in other territorial hospitals: a vast area on the river bank, a three-story main building with reception rooms, board, library, and church (Figure 5). The protruding parts of the building accommodated apartments for the director and doctors. The wards for patients were located in the sideward and rearward buildings. The plan of the hospital consisted of connecting T-shaped and H-shaped structures, such that a system of closed courtyards for patients emerged. Comfortable wooden cottages were built for the caretaking personnel on the premises of the hospital.

Figure 5. The main staircase of the Tomsk territorial hospital.

The Tomsk psychiatric hospital welcomed its first contingent of patients in the autumn of 1908. From then on, it served not only the four Siberian governorates, but also the Semipalatinsk, Akmola, and Transbaikal regions3 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Arrival of patients at the Tomsk territorial hospital.

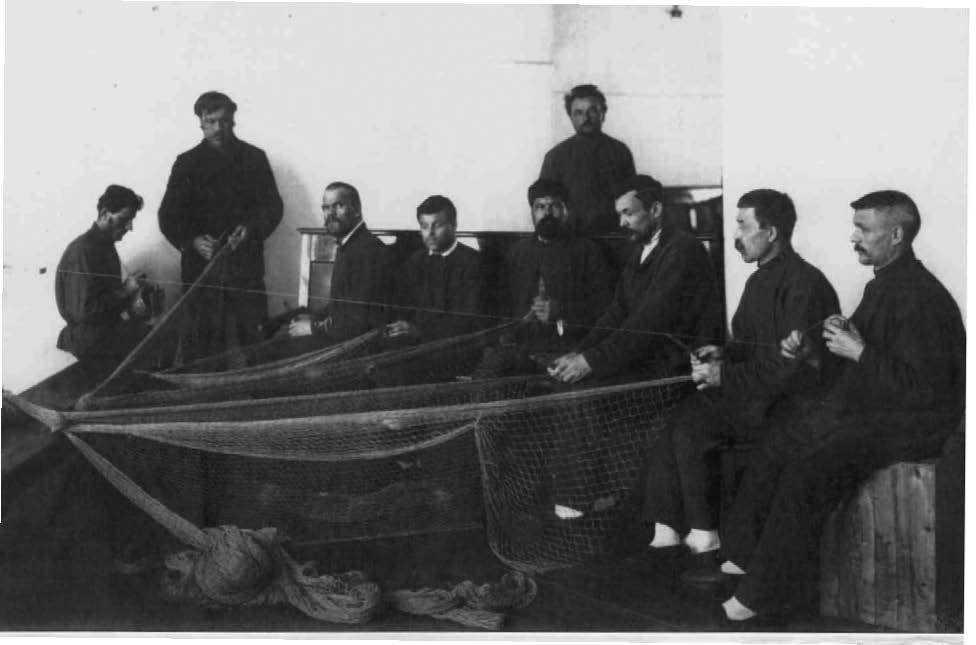

Toporkov Nikolai Nikolaevich, who until 1907 headed the Vilna territorial hospital, was appointed director of the Tomsk hospital. Notwithstanding the fact that professor Toporkov N.N. had experience in managing a large-scale institution, he had to solve many problems literally from the ground up (Figure 7). Since the Tomsk hospital served a vast territory, many of its patients after having covered quite a long distance reached it extremely exhausted and in need not only of psychiatric help, but also of general somatic treatment. It came as a no surprise that the mortality rate of patients in the first year of operation of the hospital was quite high, reaching up to 13.5%. The second problem was the influx of criminal patients. Toporkov N.N. and other doctors at the hospital launched an extensive labor therapy: shoe, tailor, bookbinding, basketry, weaving, pottery, and rope workshops were set up (Figure 8). The area of more than 400 hectares was used to grow crops and keep domestic animals. In the subsidiary farm there were even stables for breeding pedigree horses. Interestingly, in 1910, the hospital took part in the governorate exhibition of gardening and horticulture and its products were awarded a bronze medal4. Occupational therapy not only had a positive effect on the state of the mentally ill, but also opened up new perspectives for patients, as with the learning of a new craft, they gave themselves a chance to better adapt in society. Literacy teaching was practiced quite widely in the hospital. In addition, Toporkov N.N. paid attention to the organization of leisure time: holidays and dances were organized for patients, and employees of the hospital played in the wind and balalaika bands at these events (Figure 9). Despite the long odds, the Tomsk territorial hospital could find pride in its achievements as early as in the first years of its inception. For instance, in 1909 it presented its album and diagrams at the III Congress of Psychiatrists. In 1911, it took part in the International Hygienic Exhibition in Dresden, and in 1913 it showcased its achievements at the All-Russian Hygienic Exhibition in St. Petersburg, where it was awarded a small gold medal.

Figure 7. Toporkov N.N., the first director of the Tomsk territorial hospital, surrounded by colleagues.

Figure 8. Patients of the Tomsk territorial hospital busy weaving fishing nets.

Figure 8. Patients of the Tomsk territorial hospital busy weaving fishing nets.

Figure 9. Participants in amateur performances after the show.

CRIME AND TREATMENT

An important stage in the project was Moscow territorial hospital for the mentally disturbed (today, Psychiatric Clinical Hospital No. 5 of the Moscow Healthcare Department), which opened in the autumn of 1907. It was built on the same principle as the previous buildings of the project: numerous buildings were located in one common hull connected with each other through corridors (Figure 10). Initially, Moscow hospital was planned as a specialized institution; i.e., for the incarceration of patients who have committed crimes. The regulation of the hospital of 1907 stated its purpose as follows: “...for the maintenance and care of the mentally ill, especially dangerous criminals, both convicted and under investigation; to test the mental faculties of persons assigned by court ruling; as well as for the care and use of persons mentally ill, incurable, and constituting a danger to society” [11].

Figure 10. Moscow territorial hospital, 1910.

Time itself called for the establishment of a psychiatric hospital of such type. By 1907, the medical institutions of the Russian Empire had begun increasingly admitting patients convicted of various criminal offenses, and zemstvo hospitals had been instructed to admit them unconditionally. As a result, beds for other patients became scarce. A commission including the prominent psychiatrists Merzheevsky I.P., Bekhterev V.M., and Krainsky N.V. came to the conclusion that care of the mentally disturbed needed to be differentiated. Acute mentally disturbed patients and those constituting no threat to the public with chronic diseases remained under the care of the zemstvo, while a decision was made to move patients awaiting testing, prisoners, and patients constituting a public danger with chronic diseases into territorial hospitals. Therefore, the Moscow and Tomsk hospitals were built with account of the need of the state to sequester people who were deemed to be a threat to society and could not be placed in ordinary prisons due to their mental condition.

The need to build a territorial psychiatric hospital near Moscow becomes particularly obvious if one turns to the testimonies of contemporaries. One of the petitions to the government at the time stated that the mentally ill were brought to Moscow from almost all over Russia and abandoned to their fate on the streets or at railway stations. The dangerous acts they committed caused escalation of public tension. It was obvious that such patients were in need of special care and treatment. To solve the problem, the Tsar's government decided to purchase the territory of the former estate of the Obolensky princes in the village of Troitskoye, Molodinskaya volost, Podolsky district, and build a prison-type territorial psychiatric hospital. Despite the stated purpose of the establishment, the building was kept in the original spirit of the project: a picturesque area with beautiful groves, ponds, and a river; a completely autonomous farmstead; living conditions for doctors and the caretaking personnel right on the premises; and division into buildings, of which only four departments were intended for “criminal” patients. The small gardens adjoining these structures were surrounded by brick walls. There was no common fence that could be seen around the hospital, now in the first years of its operation (Figure 11). As early as at the construction stage, the hospital provided jobs to the residents of the village of Troitskoye, which by that time was in decline and, one might say, was being deserted. Throughout its history and until now, the hospital has remained a “city-forming enterprise” for the village.

Figure 11. Moscow territorial hospital. Patients taking a walk, 1910.

It should be noted that, although the Moscow territorial hospital was built at the subsequent stages of the project, it was the first example of a prison-type hospital. It is, therefore, not surprising that the audit carried out by the Ministry of Internal Affairs before the official opening of the hospital uncovered some shortcomings [12]. In his report, Yesaulov N.N., the inspector of the Moscow Medical Department, called the enormous floor area of the building with many passages and descents into a dark tunnel an unfixable flaw of the design. All that, along with the dense thickets around the hospital, played in favor of escapes. To reduce the likelihood of such incidents, screens were installed in the windows of some wards, locks appeared in isolation rooms, and ordinary window panes were replaced with durable sheet glass. In addition, control frames were installed in the doors, and metal bars were installed in the windows of the tunnel. Wide clearings were cut through the dense thickets surrounding the hospital, so that any unauthorized movement would immediately come into the view of the hospital personnel. Numerous construction shortcomings were also identified, in spite of which the hospital nevertheless opened, and in the first years of its operation it not only performed its immediate tasks, but its construction was also finally completed.

Kolotinsky Sergei Diomidovich, the first director of the Moscow Territorial Psychiatric Hospital, actually assumed the management of the entire hospital campus (Figure 12). The perimeter of the main building alone, consisting of seventeen buildings, stretched four kilometers. The two adjoining three-story buildings accommodated apartments for doctors and the so-called supervisory building with apartments for paramedical personnel. Nurses, servants, and workers resided in the basement. Heating in the hospital was provided by calorific stoves, and a narrow-gauge railroad was laid underground, used for delivering fuel to the stoves. Hot air was supplied through ducts in the walls and heated the vast areas of the hospital. Water was supplied to the hospital from a pumping station through a six-story water tower.

Figure 12. Moscow territorial hospital. Chief physician's office.

In 1908, a school was opened on the second floor of this tower for the children of the hospital personnel. This was because at the beginning, a significant part of the hospital personnel were employees of the Vinnitsa hospital who had followed the director, along with their families. Since there were not enough room in the zemstvo school, a school was established for the children of doctors and residents right on the premises of the hospital. Adjacent to the tower was a household utility building with a kitchen, a bakery, a canteen for employees, a bathhouse, a laundry, a sewing workshop, and disinfection rooms. Like other territorial hospitals, the Moscow hospital had its own power plant. Owing to that plant, not only the entire hospital town, but also part of the road to the station was illuminated.

“The extraordinary splendor, cleanliness, spaciousness, convenience” — such was the feedback about the Moscow territorial psychiatric hospital left by Leo Tolstoy, the great Russian writer. He visited the hospital in 1910, and, later, his impressions of the visit became the basis for his article “On Insanity” (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Tolstoy L.N. visits the Moscow hospital.

In 1911, Moscow territorial hospital for the mentally ill took part in the International Hygiene Exhibition in Dresden and was awarded a bronze medal, which was a clear acknowledgement of how far Russian psychiatry had come. The exposition of the hospital at the exhibition included a model of the buildings and other visual materials: reports, albums, official forms, sample documents, instructions for hospital personnel on the care and supervision of patients, as well as drawings and crafts by the mentally ill. Today, all this constitutes a significant part of the collection of the hospital’s museum (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Moscow territorial hospital. Duty doctor's room.

The First World War came as a serious shock for the territorial psychiatric hospitals. In 1914–1915, the Moscow territorial hospital admitted patients and employees from the territorial hospitals in Warsaw and Vilna. One can imagine what selfless labor and administrative talent it took to accommodate so many people. But the personnel of the Moscow hospital rose to the occasion. Local doctors even managed to stop the outbreak of cholera brought to the Moscow region along with the evacuated patients.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, Moscow territorial hospital has become an example of sound care and treatment of the mentally ill. Today, Psychiatric Clinical Hospital No. 5 of the Moscow Healthcare Department is the largest hospital in Russia providing coercive treatment. It is designed for 1,630 patients. The hospital has 27 departments: 12 general and 15 specialized. Among the above: 3 women’s departments, one department for HIV-infected patients, and one department for patients with a combined tuberculosis pathology. The hospital employs 120 doctors and 932 nurses. The main goal of the medical institution is a complete rehabilitation and resocialization of the mentally disturbed, as well as the prevention of recidivism on the part of discharged patients deemed a danger to the public. Therefore, the medical practice utilizes not only the most advanced psychopharmacological drug products, but a lot of rehabilitation activities work is also carried out, such as psychotherapy, art therapy, cultural therapy, occupational therapy in medical, and labor workshops.

Despite the length of stay in the hospital during the phase of coercive measures, preparation for discharge begins from the time of admission, for which purpose the rehabilitation potential is determined and, based on objective data, an individual medical and social rehabilitation program is prepared. A training classroom has been arranged on the premises of the Department of Medical and Social Rehabilitation (DMSR), which can accommodate up to 12 patients (learners). The classroom is equipped with Internet access and involves various forms of vocational training (both full-time and part-time). These conditions also allow for the training of both adult patients and persons under legal age using video conferencing and remote technology.

At the site of the DMSR, three sewing workshops were launched, with a total of 50 stations, which makes it possible for a large number of patients to immerse in occupational therapy. Many of them underwent professional training during their treatment and thereby gave themselves the opportunity for further employment.

As part of a need for consistency as regards coercive treatment and the effort to prevent recidivism, joint meetings are held with specialists from neuropsychiatric dispensaries who are charged with direct supervision of the patient after his/her discharge. As part of these activities, doctors tasked with carrying out compulsory outpatient monitoring and treatment after discharge get acquainted with patients and learn from the attending physicians and other hospital specialists (psychologists, social workers) all the details of the patient's clinical pattern, treatment, social status, and occupational therapy potential.

The following is worth mentioning as a separate point: several dynasties of doctors have served in the hospital, and this has contributed to the continuity of traditions and the transfer of experience from generation to generation.

In 2021, Psychiatric Clinical Hospital No. 5 of the Moscow Healthcare Department was awarded the Golden Butterfly award and a diploma of the winner of the 16th All-Russian competition “For devotion in the field of mental health” named after academician Dmitrieva T.B. in the nomination “Best Institution of the Year”.

CONCLUSION

The 19th century — the era of urbanization and rapid technological progress — brought society face to face with the problem of how best to provide care to and treat the mentally ill. Russia's response to that challenge was to develop a set of principles of structure in psychiatric care, create legislation, and to implement a project to pepper the country with a series of territorial psychiatric hospitals: the first medical establishments in its history designed on the basis of a detailed analysis of the need for and types of inpatient psychiatric care and a comprehensive discussion of the issue with leading professionals in the field and government officials.

There is little doubt that the project of territorial psychiatric hospitals took psychiatry in Russia to a whole new level, as its implementation coincided with the introduction of psychiatry into the curriculum of medical universities, and the first territorial hospitals were set up in the proximity of university cities. Subsequently, the activities of territorial hospitals provided extensive clinical material for the departments of psychiatry, and universities, in turn, communicated the latest achievements in medical science and contributed to their introduction into medical practice.

At the same time, the project of territorial psychiatric hospitals became the first experience of a new “psychiatric facility construction”. It advanced not only medical science, but also civilian architecture. Through trial and error, a balance was struck between scale and soundness. As practice shows, the principles used in the planning and management of territorial hospitals have withstood the test of time and retained their relevance today.

Finally, the project of territorial psychiatric hospitals was instrumental in shifting the emphasis in care for the mentally disturbed from isolation to treatment, in encouraging a more humane attitude towards the mentally ill and, at the same time, making care more efficient. Territorial hospitals played a decisive role in popularizing psychiatry among the general public: psychiatric hospitals began to be perceived not as frightening “lunatic asylums”, but as institutions where the mentally ill patients were given assistance and which promoted their recovery.

The fate of the territorial hospitals, which were part of the 19th century project, was different. Some of them did not survive the wars and revolutions of the 20th century and lost their original purpose, while others, despite suffering extensive damage during the Second World War, managed to recover and resume activities, albeit by then in the territories of other states. Today the Kazan, Moscow, and Tomsk hospitals continue to operate within the borders of Russia. It is worth noting that a century and a half later, they continue to advance the cause of psychiatry, honor the clinical traditions established by their first directors, and offer highly qualified comprehensive care to those who need it.

1 Archive of the Regional State Autonomous Healthcare Institution "Tomsk clinical psychiatric hospital".

2 Historical reference. Regional State Autonomous Healthcare Institution "Tomsk clinical psychiatric hospital".

3 Certificate of execution of the Highest approved opinion of the State Council on the construction of a district hospital for the mentally ill in Tomsk. Archive of the Regional State Autonomous Healthcare Institution "Tomsk clinical psychiatric hospital".

4 Historical reference. Regional State Autonomous Healthcare Institution "Tomsk clinical psychiatric pospital".