Introduction

The problem of creativity in children, outlined as early as in the works by L.S. Vygotsky, becomes more front and centre these days. The idea of nonlinearity of human development, and of that enormous potential originating in the childhood but often left unfulfilled in the adult years, stimulates minds and entails new philosophic search and psychological research [12;27;29].

Both Russian and international psychologies consider children’s narratives one of the spaces for the manifestation of children’s creativity and possible way of diagnostics of creative abilities [Piazhe, 2003; Trifonova, 2006; Shiyan, 2018; Alexander; Fehr; 35; 53; 55; 56]. This study is discussing the approbation of an assessment tool for creative abilities on the basis of children’s narratives. We followed L.S. Vygotsky’s assumption that “cultural development doesn’t create anything over and above that, which potentially exists in the natural development in the child’s behaviour” [Vygotskii, 1991, с. 8]. In other words, it is essential to find this special “seed” in children’s activities that can further sprout and develop within the scope of amplifying educational practices.

Children’s Narratives as a Way of Representation of Meanings and Emotions in Preschool Age

J. Bruner defines narrative as a story that includes a description of sequences of events, and an evaluation of these events. Moreover, this story is told from a personal perspective [Bruner Dzh. Kul’tura, 2006]. J. Piaget understood play and drawing as a manifestation of a general symbolic function that allowed the child to demonstrate his/her reaction to his/her impressions, and “to assimilate the reality into “Self” without enforcement or sanctions” [Piazhe, 2003, p. 46]. L.S. Vygotsky and other authors emphasized the syncretism of children’s activities and the development of written speech from the common root of drawing, painting, and play [Vygotskii, 1984; Trifonova, 2006; Mottweiler, 2014]. However, it seems reasonable to consider senior preschoolers’ narratives as a separate study subject, because by the end of the preschool childhood, “story-making” stands out from the play, including the children themselves. One can see the independent value of children’s narratives especially clear when adults create special conditions for all kind of narration practices, where the positions of the narrator/creator and the listener are accentuated [5;20]. Researchers note the importance of stories as a cultural way to comprehend the world, oneself in the world and pass on the experience of one’s experiences to another [Singer, 2019]. M.V. Osorina makes an interesting observation: a child in his/her drawings places him/herself (directly or through some symbolic image) in the centre of events, therefore, dominating the situation and constructing his/her own subjective line in it [Osorina, 2010].

All this confirms that a valid diagnostic tool for creative abilities should model a situation where the child would express his/her emotions and meanings through narratives.

Assessment Parameters for Children’s Creativity in Respect to Narratives: Symbolization and Dialectical Thinking

The following techniques are worth mentioning within the scope of foreign research of children’s creativity: P.A. Alexander’s technique [Alexander], creative storytelling [Fehr], and MacArthur Story Stem Battery that was initially aimed at the diagnostics of children’s emotional reactions, and was later modified for creativity diagnostics C.M. Mottweiler и M. Taylor [Mottweiler, 2014]. All these tools imply that an adult creates a problem situation (reading it out loud or playing it out with dolls), and a child has to complete the story. In all the cases, the parameters to be evaluated are similar to the ones used in the Torrance test: creativity (the number of appropriate continuations of the story), imagination (the number of continuations that go beyond the picture), novelty (the extent of uniqueness of the stories), and attractiveness (if a story is interesting to read).

However, novelty as a purely quantitative criterion of creativity assessment has been rightfully criticized in multiple works [Bogoyavlenskaya, 2007; Trifonova, 2006]. Our study was based on a different approach: the foundation for the analysis of children’s creativity was formed by various forms of mediation. Specifically, by symbolic images and dialectical structures.

The symbol, as noted by A.F. Losev, allows indirectly — through another object — to express the meaning of the phenomenon [Losev, 1991], and the symbol is not “taken” from reality, but is experienced and generated [Veraksa, 1994]. A.A. Melik-Pashaev notes that the “children’s animism is a pre-artistic prerequisite for an aesthetic attitude” [Melik-Pashaev, 2012], that is, the spiritualized images of objects and phenomena that are so common in children make children’s works related to art. In the works of O.M. Dyachenko, A.A. Melik-Pashayev, V.V. Brofman, V.T. Kudryavtsev devoted to the use of a symbol as a means of creativity, the emphasis is placed on various psychological aspects of the “work of a symbol”: on a holistic aesthetic position — the readiness to see its meaning in an object or to project the meaning on the object [Kudryavtsev, 2004; Melik-Pashaev, 2012], on the ability to be in touch with one’s own emotions [Brofman, 2019], on the ability to discover new aspects of the object in a new context, not to be limited by the plane of the visible [D’yachenko, 1987].

The concept of dialectical thinking, in comparison with the creativity concept of J. Guilford and E. Torrance, describes not the quantitative side of creative thinking, but the qualitative one. In other words, creative thinking is based on dialectical logic, instead of formal [Besseches, 2018; Veraksa, 2006]. Therefore, while formal logical thinking is governed by the laws of non-contradiction and excluded middle, dialectical thinking is capable of solving contradictory situations and reflecting the processes of development and transition. Research works by N.E. Veraksa, A.K. Belolutskaya, E.E. Krashaninnikov, I.B. Shiyan, and O.A. Shiyan demonstrated that dialectical thinking is something preschoolers actually have, and it is an independent developmental line, different from formal logical thinking described by J. Piaget [2;13;26]. Dialectical thinking allows reflecting the world in its dynamic, seeing the frontiers of the transformation of objects, and building an “inverse world”. This is what helps the child understand the essence of the reality (it was L.S. Vygotsky who underlined the significance of the “inversions” for children’s understanding of the world in “The psychology of art”), and resolve contradictory, paradoxical situations. Dialectical thinking is what associates the way of thinking of a preschooler who hasn’t mastered formal logical laws, yet, with the thinking of scientists that find themselves facing limitary paradoxes in their attempts to explain the world (for instance, take the statement that light is both a wave and a particle).

N.E. Veraksa and O.M. Dyachenko indicated that in preschool age, children can operate three types of means for familiarization with this reality: symbolic, transforming, and normative. This assumption can be illustrated by the phenomenon of anticipation appearing when children retell a fairy tale [Veraksa, 1994]. In order to confirm that symbolic means and dialectical thinking can be used by children in their narratives, we held a pilot study that analysed the so-called “children’s free narratives”. These stories were created in kindergartens with a long tradition of writing down, discussing, and even playing out such narratives. 1312 narratives were written down in individual notebooks (one for each child), and qualitative analysis of this data revealed that the stories contained both symbols and dialectical thinking “moves”. It means that symbolization and operating with the opposites are intrinsic for children’s narratives.

“Three Stories”, a Diagnostic Tool for Creative Abilities in Preschoolers

We set the task of elaborating a diagnostic tool that could be tested in different educational environments. The analysis of theoretical sources, as well as a qualitative analysis of “free” narratives, made it possible to determine the requirements for it. First, it was important to create a situation that would evoke an emotional reaction that would make sense for the child. Secondly, the situation, in order to provoke a creative solution, must contain an intellectual “challenge”, an embarrassment. L.S. Vygotsky notes that “the desire for creativity is always inversely proportional to the simplicity of the environment” [Vygotskii, 2020, p.35]. Thirdly, the task should be open, leaving the child space of freedom.

The “Three Stories” technique includes the following subtests: “Fire”, “Scary — Not Scary” and “Funny Story”. In all three cases, the children were asked to draw a story at first, and then the adult wrote it down under the dictation of the child, since children most often create a text both visual and verbal. When performing the “Fire” subtest, a contradictory situation was created in the discussion in a small group — the children actively discussed whether fire is dangerous or useful, then they were individually asked to compose a “tale about fire”. In the second subtest, children were asked to tell a story “about someone scary, but the story was not scary”. It was assumed that the creative move could manifest itself in the ways in which the scary character would be “neutralized” in the story. In the third subtest (“Funny Story”), the child was asked to make up a story to make a girl laugh who no one can make laugh. Creating this subtest, we were based on the data of numerous studies, which testify to the importance of the phenomenon of funny for culture in general and for child development in particular [1;22;23;28;32].

The Key to the Analysis of Manifestations of Creativity in Children’s Narratives (“Three Stories” Technique)

All the stories were analysed from the perspective of two components of creative abilities, i.e. the presence of symbolic images and dialectical transformations in them.

Symbolic image as a reflection of creative abilities in children’s narratives. We registered the presence of a symbolic image in the story, if there was an animated object acting in accordance with the logic of the image, and bearing the author’s evaluation; or if the character was described not only from exterior, but also from the perspective of his/her internal emotions. In the scope of the analysis of children’s narratives we considered the actions of the character be “in accordance with the logic of the image” only if emotional details served for the deployment of the image of the character. Here is an example of such a symbolic image: (Luka, 7 years old): “This is fire. And it can’t kindle itself! So, they kicked it out of the house. And out of revenge, he managed to set the house on fire. That’s it!” In this case, the fire as the protagonist behaves exactly as a fire should. We can see a full and true deployment of the image in the style of H.C. Andersen’s fairy tales. In those stories, all characters, starting from a darning needle, and finishing with a pan, express human passions, and act in accordance with the logic of emotional characteristics of the object.

Dialectical thinking as manifestation of creative abilities in children’s narratives.

Dialectical structures appear in the stories as the opposites and their interactions of all kinds: transformations, integrations, and mediations. We identified a separate “Transformation” parameter for the purpose of the evaluation of manifestations of dialectical thinking in children’s narratives. Points were assigned for the appearance of contrapositions in the text (because it’s already a sign of retaining of the opposites), for transformations (for example, when bad fire turns into a good one; conventional relationship gets inverse), and for the introduction of ambivalent characters.

All suggested tasks imply an opportunity to operate with the opposites, at this or that extent. For instance, in the analysis of “Fire” subtest we checked if the child succeeded in retaining the ambivalent nature of the fire. In the “Scary/Not Scary” subtest, we looked for the transformation of a scary thing into not scary, or for the introduction of an ambivalent character (a scary character behaving in a funny way, performing good deeds, or appearing as a small one). In the evaluation of “A Funny Story” subtest two categories of transforming answers were distinguished: “Mismatch of expectations” and “Transformations”. The former was registered when a character or an object behaved in a non-standard way (all kind of falls, absurd situations, exaggerations). “Transformation” meant a creation of an inverse situation, where the central relationship wasn’t just different; it was the opposite to the “standard” one.

Here is an example of dialectical structures me met in the stories. “Fire” subtest (Stepan, 7 years old): “Volcanos can be useful. Say, there is a volcano, but the population can be saved from it. If we drill channels in the spots where lava accumulates, we can redirect lava flows away from the city. We can direct them into the river, if water forms and obstacle. When water and magma mix together, magma will solidify and turn into stone. Then cars can drive on this “concrete”. Or we could direct lava to some dry spring. As soon as it starts to rain, it will also turn into concrete. The end!” The child took a dangerous object (a volcano) and created a situation where it could actually be beneficious. The story also contained a fusion of two opposite substances, and appearance of the third one.

It’s important to note, that despite apparent ingenuousness of dialectical transformations, we didn’t meet them in the children’s stories too often. Speculating on the fire, the majority characterized only one facet of it (mostly described it as something dangerous). Or, in the “Scary/Not Scary” subtest, the character still remained scary (as one boy frankly said, “There is nothing I can do about it”), and a funny story turned out to be a story about something funny, for example, a clown. The events, though, were not funny at all.

The structuredness of the narratives was examined as a separate parameter. We applied a well-approbated approach by W. Labov and J. Waletzky that is normally used for the analysis of children’s narratives. It evaluates the proximity of the story to a high point one, i.e. if it has an opening, a high point, and a climax [57]. Moreover, for the evaluation of the full-fledged stories, we also took into account the appearance of additional characters or events, and used V.Y. Propp’s analysis.

Approbation Design

Our goal was to analyse the correlation of the results of our diagnostics of creative abilities through narratives, with the results of already existing assessment techniques for creativity in children. For this purpose,, we selected a number of diagnostic tools matching our parameters of the evaluation of children’s narratives, to the maximum.

Firstly, we analysed the relationship of the transformations in the narratives: “What can be simultaneously?” [Veraksa, 2006], and “Dialectical Stories” (I.B. Shiyan [526]). Then we matched different aspects of children’s creativity with the “symbolic realism of imagination” (“Inkbottle” technique by V.T. Kudryavtsev [Kudryavtsev, 2004]). Thirdly, we matched the manifestations of different aspects of children’s creativity with the performance in figurative subtest of Torrance test. The latter assesses the ability to complete a detail to create a new whole, and is often used for the diagnostics of children’s imagination.

We assumed that the validity of our technique could prove itself through its capacity to reveal significant differences between children from the groups, contrasting in the parameter of quality of education. All calculations were carried out at a significance level of 0,05.

Sample. Senior preschool groups from two Moscow schools were selected for the study. These institutions followed different educational programs. 28 children from one school, and 29 from another, took part in the project. External expert evaluation was performed in the groups by the specialists from the Laboratory of the Child Development, Research Institute of System Projects, Moscow City University of Education). Two tools were used: ECERS-3 and CASRS (Creative Ability Support Rating Scale). The first one allows the assessment of educational environment (such as the equipment, materials, child-adult interaction, amount of time dedicated for free play, the conditions for the development of speech and thinking, and so on) and is focused on the support of children’s independency. It also covers children’s interests and needs. The second tool was developed by the Laboratory as an extension of the above mentioned scales specifically for the evaluation of the conditions for the development of creative abilities [Belolutskaya, 2021].

The score difference was calculated by means of T-Student test and came out to be significant (p=0,004). CAD scale score also demonstrated significant difference (p=0,008 for T-student test; p=0,015 for Sample Wilcoxon rank sum test). The comparison of educational programs revealed that the kindergartens that obtained higher score in external evaluation practiced writing down children’s narratives, as it was mentioned earlier. Moreover, no conventional classes for speech development were scheduled there; favourable conditions for such development were created in the scope of multiple event-based workshops. The second kindergarten that participated in the study didn’t have this tradition, and children’s narratives were not registered at all. Instead, they had conventional speech development classes (under V.V. Gerbova’s program). Thus, the results of the quantitative and qualitative analysis allowed categorizing the groups that participated in the study as contrasting, by the parameter of the quality of education in general, and more specifically, of the conditions for the development of creative abilities. Further we will refer to the group with lower quality of education as Group 1, and to the more advanced group, as Group 2.

Results

Discriminatory power of “Three Stories” technique. We analysed the discriminatory power of the new tool “Three Stories” by defining Ferguson’s δ for our sample by each parameter. The value of δ was high for “Symbolization” (0,86), “Transformation” (0,95), and “Narrative Structure” parameter (0,96). It proves that this tool can assess a sample differentially, and distinguish the extent of representativity of a certain quality in the respondents.

The correlation analysis revealed a significant correlation between such parameters of narratives as symbolization and dialectical thinking (see Table 1).

Herewith, no significant correlations were registered for “Narrative Structure” parameter and “Symbolization” or “Transformations”. It only confirms our assumption that symbolization and dialectical thinking belong to the same cluster of creative abilities, comparing to the narrative structure which rather characterizes the mastering of a cultural norm.

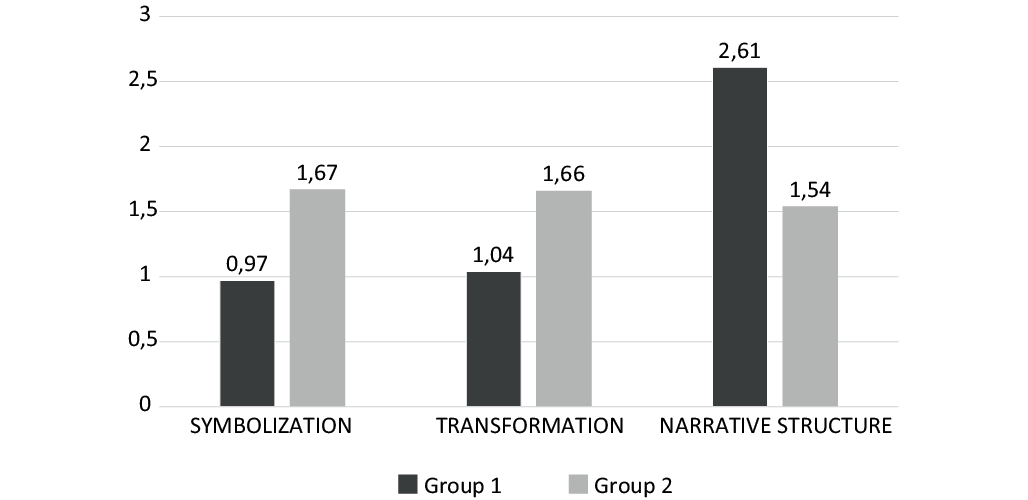

Figure 1 represents the diagram of results of children’s narratives assessment in contrasting groups, by individual parameters: “Symbolization”, “Transformation”, and “Narrative Structure”. One can notice that in respect to the use of symbol and transformations (i.e. “Creative abilities” cluster), the group with a higher education quality was ahead of the less advanced group. Interestingly, when it comes to “Narrative Structure”, the situation is reverse; yet, the difference was significant as well.

The relatively small sample size makes it undesirable to use the Student’s t-test to test for the significance of differences, so we limited ourselves to using the Two Sample Wilcoxon rank sum test. Differences are significant for all parameters of narrative assessment: for the “Symbolization” parameter according to the Two Sample Wilcoxon rank sum test at p-value 0,032; for the “Transformation” parameter according to Two Sample Wilcoxon rank sum test at P-value 0,029; according to the “Narrative Structure” parameter according to the Two Sample Wilcoxon rank sum test with P-value 0,00001.

Significant correlations were found in the “transformation” parameter in narratives with the results of methods diagnosing dialectical thinking: “What can be at the same time?” (Pearson’s coefficient of cor. 0,38, p-value 0,0036; Spearman’s coefficient of cor. 0,41, p-value 0,0016) and “Dialectical Stories” (Pearson’s coefficient 0,3, p-value 0,0292; Spearman’s coefficient 0,41, p-value 0,0016).

The relationship between the results of the “Three Stories” methodology in terms of “Symbolization” and “Narrative Structure” parameters with the results of diagnosing dialectical thinking is not significant. This is consistent with the results of a previous study, in which the structure of narratives also did not correlate with the results of diagnosing dialectical thinking [Shiyan, 2018].

Also, there was no significant correlation between the results of performing the technique that diagnoses the “symbolic realism of the imagination” (“Inkwell” by V.T. Kudryavtsev), and such a parameter as “Symbolization” in the “Three Stories” technique.

The general results of the figure subtest of the E. Torrance test correlate only with such a parameter of children’s stories as “Narrative structure” (Pearson’s coefficient 0,38, p-value 0,004; Spearman’s coefficient 0,41, p-value 0.002, significance at the 0,01 level). At the same time, the “Narrative Structure” parameter of the “Three Stories” methodology significantly correlates not only with the total score of the Torrens test, but also with its individual parameters —“Originality”, “Flexibility” and “Elaboration”.

Discussion

We found that in the narratives created during the “Three Stories” technique, all three types of means of reflecting reality are detected: symbolic, transformative, and normative. This suggests that when writing stories, children are involved both affectively and intellectually.

A significant relationship between such parameters of the “Three Stories” technique as “symbolization” and “transformations” allows us to raise the question of the role of a symbol in reflecting transitivity and uncertainty. This may mean that the symbol allows you to express meanings where there are no ready-made models (which was pointed out, in particular, by A.F. Losev [Losev, 1991]). The fact that these two parameters, while correlating with each other, do not correlate with the structure of the created story, suggests that, firstly, creative abilities stand out in a cluster separate from the normative one, and secondly, within this cluster there are two qualitatively different component — symbolic and sign. This fact is consistent with the semiotic studies of Y.M. Lotman, who spoke about the bipolar structure of cultural phenomena [Lotman, 1992].

We found that in kindergarten, where the educational environment is more focused on supporting children’s initiative and creativity, symbolic and transformative means are found in the narratives significantly more often, which indicates the ability of the “Three Stories” technique to distinguish the educational results of children studying in qualitative terms. various educational programs. At the same time, the fact that in a kindergarten with a higher quality of the environment, children were significantly less likely to create a well-structured detailed narrative requires a separate analysis. It can be assumed that a higher score on the “structured story” is sometimes associated not so much with mastering the cultural norm of writing stories, but with the assimilation of some “narrative template”.

The results of the “Three stories” technique in terms of the “transformation” parameter (the reflection of opposites and their mutual transitions, transformations, ambivalent characters, etc.) correlate with the results of the methods that diagnose dialectical thinking (“What can be at the same time” and “Dialectical stories”), which allows us to speak about the validity of the “Three Stories” for diagnosing dialectical thinking. At the same time, unlike the listed tools, the “Three Stories” technique allows to identify the use of all three types of tools, which makes it more environmentally valid.

At the same time, the absence of significant correlations of symbolization in narratives with the results of diagnosing the phenomenon of “symbolic realism of the imagination”, described by V.T. Kudryavtsev, allows us to conclude that the creation of an artistic symbolic image within the narrative is governed by different rules than a production of an image while solving a problem.

The study found no correlations between the figurative subtest of the E. Torrens test and the parameters that we attributed to creative abilities — with dialectical transformations and symbolizations in the children’s stories; this fact, from our point of view, is explained by the qualitative difference between the forms of mediation, which were the subject of our study, and the understanding of the phenomenon of creativity, which underlies the methodology of E. Torrens. The presence of a correlation between the results of the figurative subtest of the E. Torrance test and the “Narrative structure” parameter suggests that the construction of a coherent logical text requires the ability to correlate individual elements of the text (outset, climax, denouement) and its holistic intention, as in the Torrance test, it is necessary to be able to see the original element in the context of the new integer. These results provide grounds for further research into the psychological mechanisms of creating a classical narrative structure.

Conclusions

The result of testing the “Three Stories” technique showed that children are really involved in the storytelling process with a high level of motivation, which allows us to count on the organicity of the simulated situation and on the relevance of narratives for diagnosing children’s creativity.

Despite the fact that the importance of children’s stories and drawings for the development of writing as a cultural practice in the future has been repeatedly noted by researchers (see: L.S. Vygotsky [Vygotskii, 1984], A.M. Lobok on the birth of writing from the practice of communication [Lobok, 1996]), Today, within the framework of the “speech development classes”, on the one hand, children’s stories that arise inside the director’s and role-playing game and together with the drawing are ignored, and on the other hand, the emphasis is placed primarily on the structure of the narrative, but not on its creative aspects. Such ignoring can be, in particular, one of the reasons for the difficulties that arise when mastering written speech with the creation of an author’s statement, which researchers talk about [9;19].

The important idea for cultural-historical psychology, that childhood is resourceful for the development of creativity, is relevant not only for building modern educational practices but also for understanding the “ideal forms” of creativity.

Table 1

Relationship of Parameters in “Three Stories” Technique

|

Parameters |

Pearson correlation coefficient |

P-value |

Spearman correlation coefficient |

P-value |

Nature of relationship |

|

“Symbolization” and “Transformation” |

0,54 |

0,000013 |

0,55 |

0,000011 |

Significant at the level of 0,01 |

|

“Symbolization” and “Narrative Structure” |

0,18 |

0,190544 |

0,15 |

0,26555 |

Not significant |

|

“Transformation” and “Narrative Structure” |

0,11 |

0,423077 |

0,08 |

0,565114 |

Not significant |

Fig. 1. Average score comparison for Group 1 and 2 by three parameters of “Three Stories” technique