To manage

Comedy films attract the attention of researchers relatively rarely. The reason for this, apparently, is the apparent obviousness of their positive, i.e., problem-free, impact. But such "evidence" exists if we limit the consideration of the psychological effect that arises from watching a film — at the everyday, and often at the research level, — to the emotional sphere. The American film researcher G. Smith, expressing this idea, figuratively described cinema as a machine for producing emotions [Smith, 2003]. From this perspective, comedy "produces" positive emotions, and it is easy to take this as a sufficient sign ofa positive impact in all senses. In fact, the influence of cinema on consciousness and на the human psyche in general is complex and multifaceted, and it affects not only the emotional sphere, but also self-consciousness, attitudes, cognitive functions, etc. [see for example: 18; 30]. Therefore, the evidence of the unproblematic positive impact of comedy on a person's consciousness can be deceptive. For example, in one of our studies, it was found that a comedy film reduces the level of connectedness of consciousness [Yanovsky, 2017a]. It is no coincidence that sociologist S.G.Kara-Murza noted the possibility of using humor and irony to destroy psychological protection from manipulation of consciousness [Kara-Murza, 2018]. However, in general, studies that reveal the essence of the influence of films of the comedy genre are almost absent and this topic itself is not covered by attention. We set the task of theoretical analysis and empirical study of this influence.

The object of our research was the psychological impact of a comedy film on the audience. We have limited the subject of our research to identifying the featuresof the impact of a comedy film on the Self-concept.

There are different versions of ideas about what the psychological content of the comic consists of: resolving contradictions, releasing emotional tension (catharsis), achieving a sense of superiority, and a form of psychological play [Dmitriev, 2005; Martin, 2009; Eitzen, 1999]. Are these options alternative? In our opinion, they are compatible and are aspects of a complex psychological phenomenon.

Let's start with an overview of the concepts of the comic as a special phenomenon. It should be noted that the main ideas of possible interpretations of the comic were already developed by the classics of philosophy and art criticism. Modern psychological studies of humor often offer only transcriptions of the ideas of previously developedclassical doctrines of the comic, or a simplified representation of them as a prehistory to the modern understanding of the comic "without prejudice", as a stimulus that causes obviously positive and useful emotions [Martin, 2009].

Review of classic comic art concepts

According to Plato, the reason for laughter is the discrepancy between the form and essence of a person, the discrepancy between who he claims to be and who he really is. Laughter itself is a mixture of sadness and pleasure: sadness at someone else's delusion and pleasure at the absence of delusion in the laughing person. In this sense, according to Plato, laughter is akin to gloating and, therefore, has an admixture of immorality [8, pp. 125-127—]. It should be noted that the view of T. Hobbes is similar to Plato's idea of the comic: the passion of laughter is a sudden feeling of vanity from being superior to people who have any shortcomings [ibid., p. 138]. But, unlike Plato, Hobbes did not see this as a reason for a negative assessment.

According to Aristotle, "...comedy < ... > is an imitation of (people)who are rotten, although not in all their meanness: after all, the funny is (only) part of the ugly. In fact, the ridiculous is a certain mistake and ugliness, but painless and harmless" [Sochineniya [Essays in, 1983, p. 650]. You can interpret this as the fact that funny is something ugly-evil, but helpless. This is how the image of the object of ridicule is usually drawn. In this sense, Aristotle's opinion reflects comicality as if in the first person: not an analysis of the phenomenon of the comic as such, but a description of the impression of the comic object in someone who expresses his attitude to the object.

I. Kant: "Laughter is an affect from the sudden transformation of expectation into nothing" [Kant, 1964, p. 352], i.e. it is a discharge, a release of tension. Therefore, according to Kant, laughter is useful and has a healing effect.

F. Schelling: in the comedy "...necessity falls into the subject, and freedom-into the object " [Schelling, 1966, p. 419]. This means that the person who is internally unfree and rigid in the conditions that provide freedom is ridiculous.

G. Hegel's reflection is insightful: "The universal soil of comedy is a world where a person as a subject has made himself the complete master of everything that is significant for him as the essential content of his knowledge and accomplishment: a world whose goals destroy themselves by their insignificance" [Hegel, 1971, p. 579]. So comedy arises from a position of "omniscience", i.e., knowledge of the helplessness and "stupidity" of the world.

A detailed and in-depth analysis of the comic was given by the German esthetician of the XVIII—XIX centuries, Jean-Paul [Jean Paul. Prigotovitel'naya, 1981]. His concept of the comic reflects, among other things, much of what was expressed by thinkers before him. Jean-Paul points out that nature is never funny. Only people or what we humanize can be funny. At the same time, it may not be the moral flaws of a person that are funny, but the mental delusions that are revealed in inadequate actions and aspirations. It is necessary that we project our knowledge on these aspirations (we must understand the inadequacy of these aspirations). The viewer must know more than the object of laughter, must be sure that he knows the "truth", this is an important condition for laughing at the object (this is taken into account in modern technologies for creating comedies [Kaplan, 2017]). And such knowledge may actually be our imagination, but it doesn't matter. Jean-Paul summarizes this into three components of the funny: 1) the aspiration of the object of laughter, which contradicts its position; 2) this position itself; 3) the observer with his own view, the object's behavior [Jean Paul. Prigotovitel'naya, 1981, p.139]. Therefore, "...every humorist's Ego plays first fiddle" [Jean Paul. Prigotovitel'naya, 1981, p. 155]. As a result, humor creates favorable conditions for the formation of vanity.

A deep study of the comic was undertaken by the famous Soviet philologist V. Ya. Propp [Propp, 1976]. According to Propp, the comic can be different, but it always contains mockery [Propp, 1976, p. 16], which in its developed form becomes an "instrument of destruction" [Propp, 1976, p.31]. An important role in the comical effect is played by" obscuring " or removing "obscuring" [Propp, 1976, p. 28]. Thus, the effect of comicality arises from the sudden discovery of initially imperceptible, as if obscured, shortcomings of the object, its inferiority, i.e., the discrepancy between the internal actions (aspirations) of the object and the external forms of their manifestation [Propp, 1976, p. 29]. In general, laughter implies a detached attitude; therefore, in particular, laughing at oneself is possible only as a view of oneself from the outside, for example, at oneself in the past.

M. M. Bakhtin interpreted laughter as an expression of the world of dialogical polysubject carnival culture, as opposed to the official culture —monological, as if subject-object [Bakhtin, 1990]. That is, laughter is a phenomenon that presupposes an image of the world, built as a system of intersubjective relations. Laughter is also an expression of vital force. In general, among philosophers and psychologists, the point of view that the comic is associated with an increase in vital energy, an increase in cognitive flexibility, etc. is quite popular [Ivanova, 2017; Taldykina, 2010].

The opposite concept of Bakhtin (and close to the ideas of Schelling) is the concept of funny in A. Bergson [Bergson, 1999]. According to Bergson, the comic is a human consciousness reduced to automatism, which finds itself in contradiction with the world. This representation of Bergson is part of his general concept, in which all phenomena are evaluated within the framework of the "vital impulse — inert matter"scale. The comic, therefore, in Bergson is evaluated as an expression of the loss of vital energy and falling into inertia. Therefore, according to Bergson, the comic and laughter itself require a short-term "anesthesia of the heart" [Bergson, 1999].

Consonant with Bergson is the point of view of Z. Freud. According to Freud, laughter is a defense mechanism that combines the escape reflex (discharge reaction) and aggression [Freud, 2015]. At the same time, in his later article "Humor" (1928), he states: humor is "...the triumph of narcissism, in which the inviolability of the individual has triumphantly established itself" [Freud, 1995, p.282]. In humor, a person takes a detached position: "I refuse to take damage under the influence of reality " (ibid.).

These are the classic points of view on the comic. Let's summarize them.

So, in the comic:

- the object of laughter showsa discrepancy, a contradiction (most often between the form and content).

- the object of laughter is only a person or something humanized, i.e. the subject.

- there is a contrast between the subject-observer and the object (which is ridiculed), while the subject is detached from the object, looks at it "from the side" or even "from above", from a position of superiority ("Comedy is not when you watch someone who does something funny, but when you look at the object from the outside"). when you watch someone who is looking at someone who is doing something funny " [Kaplan, 2017, p. 188]);

- the position of the subject (observer) is devoid of variability, he feels himself the "master" of knowledge, the "master" of vision, i.e. the owner of absolute measures that allow us to evaluate the object (i.e., this position is egocentric, in the terminology of J. Piaget);

- the subject evaluates the object and, as it were, removes the "barrier": he exposes it, sees in it the ugly, shortcomings (mistakes, inferiority, ugliness, reduction to automatism, aspirations that do not correspond to its position); at first this is hidden from the observer, but then he suddenly removes the "barrier", or simply it knows in advance that the object actually exists.

- there is a change of states, a sudden "reset" of expectations, turning them into nothing;

- some form of aggression against the target is possible.

Ideas about humor and the comic in psychology

Following the classics, psychologists interpret the comic as a manifestation of contradictions, inconsistencies that we encounter, and as a form of their resolution [Kuznetsova, 1984]. This is an integral component of the comic, I mentionalmost everything about it, but other components are also indicated.

T. V. Semenova draws attention to two properties of the comic: 1) it is connected with the interaction of people, especially with the perceptual side of social contact; 2) it is connected with the realization of human freedom [Semenova, 2014].

Comic and humor are interrelated concepts, aspects of the same whole; at the same time, comic is a characteristic of an object, humor is a way of either seeing the comic in an object, or creating and projecting qualities that make it comical on the object [Luk, 1977]. It is clear, therefore, that psychologists are more likely to theorize about humor.

Foreign researchers consider humor in various aspects: as active cheerfulness, cognitive ability, emotional reaction, coping strategy, etc. [Kiseleva, 2019]. Great importance is attached to the classification of different types of humor [Martin, 2009; Kiseleva, 2019]. Humor is considered more often through the prism of a psychoanalytic or cognitive approach [Martin, 2009]. As a rule, humor is considered as a source of positive "useful" emotions that improve well-being, increase adaptability, creativity, etc. [Martin, 2009]. According to N. F. Kuznetsova, this role of humor is even absolutized [Kuznetsova, 1984].

Following A. Maslow, humor is also considered as a phenomenon characteristic of a self-actualizing personality [Kiyamova, 2013]. Its potential as a psychotherapy factor is described [Kara, 2017].

Humor is also assessed as a systemic property of the individual [Ershova, 2012], as part of emotional intelligence [Gorbunov, 2015].

At the same time, research data show a link between the sense of humor and self-esteem, a sense of self-worth [Omarova, 2021], subjectivity and egocentricity [Kiyamova, 2013]. The presence of an element of egocentricity and a tendency to self-affirmation in humor was pointed out by A. Adler [Adler, 1997].

In general, we see in modern researchers the continuation and variations of ideas discussed by classical philosophers. There is a noticeable emphasis on the possible therapeutic effect of humor. At the same time, there are empirical confirmations of the idea that humor is not only a source of positive emotions, but also it is associated in a certain way with intersubjective relationships and attitudesin relationships.

The image of the world created by the comic

A movie does not just provide a set of visual and auditory stimuli, but creates a limited virtual world and through this sets a certain vision of the real world. Thus, the researcher of psychology of cinema J. Mitri says: "The film impulse imposes on us a vision of the world organized in a certain sense" [Mitry, 1998, p. 156]. What kind of vision of the world does the "movie pulse" of comedy create?

Based on the above generalization of the properties of the comic phenomenon, we can assume that the world of comedy is a world of intersubjective relations (the object of laughter is necessarily another subject). But this is a world of unequal relations: there is a kind of" omniscient "subject and there are" inferior " subjects, which thereby become objects of evaluating attitude, ridicule. The "omniscient" subject is a kind of "master" of knowledge, which allows him to see and know in others what they do not know. As a result of this, sudden revelations occur: some subjects embedded in a system of equal inter-subject relations suddenly turn out tobe inferior (or somehow inferior), i.e. objects. The unity, the balance of the system of inter-subject relations is suddenly disrupted, and a kind of energy reset occurs. But if we take into account that the system of relations is integral and tends to prolong its existence, after the imbalance is disturbed, they should undergo a reverse compensatory process, the restoration of equilibrium, should occur. The recovery function can be performed by any of the participants in this system.

So, comedy is always a competition of subjects: who is smart, who is stupid, who is more cunning than others, and who is kind. It is built as an intricate network, a" web " of relationships, so the nodes of relationships — positions-should play an important role here. Given what has been said about the world of comedy, we believe that the minimum set of basic possible positions can be as follows.

- "Omniscient" subject-an observer who can reveal the inferiority, stupidity or ugliness of another subject. Let's call it the "Whistleblower". We believe that exposure to a certain emotional charge can transform into a position of punishment; therefore, a possible modification of the Whistleblower is the "Punisher".

- A subject who loses a competition with a Whistleblower and, thanks to exposure, turns out to be inferior, i.e., turns into an object of negative assessments and ridicule. Conditionally — "Fool".

- The subject who does not play the competition with the Whistleblower-successfully conceals his shortcomings and intentions from exposure. Conditionally — "Rogue".

- Someone who triesto restore and correct the balance in the system of broken relationships. Conditionally — "Good Man" ("Rescuer").

(One can see in these four positions a similarity to the well-known "Karpman's dramatic triangle": Stalker, Victim, Rescuer, [Karpman, 1968] with the addition of “Traitor” [Yanovsky, 2012a]:

Stalker — Whistleblower.

Victim — Fool.

Traitor — Rogue.

Good Man — Rescuer.

The similarity, in our opinion, suggests that comedy is a reflection of the basic archetypal structures that are "exploited" in the game relationship scenarios described in transactional analysis [Bern, 1999].)

A thought experiment shows that comedy and its types are built on a combination of these positions. So, the classic master of the comic, the clown, is a combination of the hypostases of the Fool and the Rogue. The court jester had to be a Whistleblower once. Good Man + Fool + Whistleblower is also a typical character in comedies and comic literature, classic examples: Don Quixote, Charlie Chaplin's characters, Shurik from Gaidai's films. A combination of a Rogue and a Whistleblower: Ostap Bender, Khlestakov from The Inspector General, Chichikov from Dead Souls. Whistleblower (Punisher) + Dodger + Good-Man Rescuer: Woland from The Master and Margarita. Coverage of all four positions-Whistleblower (Punisher) + Good-Man Rescuer + Clown (Fool + Rogue) — the role of the popular Ukrainian comedian Zelensky and, perhaps, the secret of his success.

Funny episodes in comedies are usually situations of exposure. The fullness of the comic is achieved when the characters are mutually exposed, when the characters also turn out to be one for each other and cunning Rascals, and supposedly Rescuers, and deceived Fools, and Whistleblowers. A vivid example is "Student" and "Fedya" from the movie "Operation S and other adventures of Shurik "(Fig. 1, part of the movie "On the construction site", scene with a fly).

Figure 1. Still from the movie "Operation Y and other adventures of Shurik"

In this scene, all the facets of the comic described above are intertwined: the game of mutual help-rescue, mutual deceit, mutual naivety — stupidity, and exposing each other (with the transition to punitive actions).

Thus, exposing stupidity, trickery is an integral element of the plot situations of any comedy.

Let's try to identify the psychological and cognitive basis of the comic world. To analyze this basis, we will apply J. Piaget's model of three types of spontaneous structuring of space by human consciousness at different stages of its ontogenesis [Piaget, 1948]. The basis for applying this Piaget model is that the world of intersubject relations has a structure that can be understood in one way or another as a certain space. According to Piaget, one of the three types, and, in our opinion, coincides in characteristics with the world of the comic, is the projection space (along with the space of places and Euclidean space) [Piaget, 1948]. This is the world as a system of forms perceived by one or another observer, fixed in a certain position. The object here exists only as a projection from a certain position of its form to the subject. The projection space is created "...by the intervention of an observer or "point of view", in relation to which the figures are projected <...> Therefore, the projective geometry can be genetically characterized as the geometry of points of view" [38, p. 554-555—]. As a result, the genetically original cognitive operation that generates this childhood — «of space is "aiming", i.e., the subject's vision of an object from a certain position; in this case, another object is used as a means ("sight") (as in real aiming, a front sight) (ibid.). In such "aiming", the subject does not deal with the object itself, but with its projection (= shape, image). In the projection space, an important role is played by straight lines — projection lines, the shortestpaths from the object to the observer. It is they — as a kind of relations, connections-that, as it were, define the structure of such a space. A characteristic feature of the projection space, according to Piaget — is the absolutization — due non - reflexing to the unreflectability — of the observer's position-the subject, its reference system. This fixed position of the observer and the fixed frame of reference lead to egocentrism.

Egocentrism, the absolutization of one's own frame of reference, obsession with forms (how an object looks), the possibility of straight-line (as if simplified) actions aimed not at a practical result, but only at expressing attitudes to other subjects, exposure to illusions (forms that "obscure" real objects — - this is what is inherent in the world, organized as a projection space. This corresponds to the factors described above that are involved in creating the comical effect. In particular, the cognitive action of "aiming", which is basic for the projection space, essentially coincides with the cognitive operation that constitutes the effect of comicality: with the exposure of the inferiority of another subject.

The implementation of "aiming" just creates a set of basic positions in comedy. Thus, the " sighter "is a" Whistleblower"; the object of aiming, if it is exposed, is a" Fool"; if it is not exposed, it is a" Rogue"; and the subject that maintains the balance in the system of relations that is disturbed by revelations, is a" Good — natured "("Rescuer").

If cinema is considered as an art form that reproduces, in one way or another, the experience of "being present in a situation" [Yanovsky, 2017], then, judging by the above characteristics, the film comedy will mainly exploit this type of inclusion in the situation, which is expressed in the experience of self-affirmation [Yanovsky, 2017]. Here the subject, relying on a kind of absolutized frame of reference, opposes himself to the object and evaluates it, thereby asserting himself.

The variants of understanding the essence of the comic presented at the beginning of the article can be considered as aspects of the formed projection space, in which the self-affirmation of subjects is realized, their points of view collide, and the balance in the system of relations is disturbed and regained.

Procedure and methods of research

For preliminary confirmation of our understanding of the comic, we conducted a pilot study.

The aim of the study was to test the assumption that a comedy film forms a viewer's self-image associated with self-affirmation. At the same time, we also assumed that there would be signs of any of the positions described above: Rogue, Fool, Whistleblower (Punisher), Good-Man (Rescuer). In this case, most likely, there are signs of the position that most directly implements self-affirmation: The whistleblower.

Identifying signs of self-affirmation would be an indirect confirmation that comedy forms the viewer's image of the world, structured as a projection space, with the consequences that follow from this (egocentrism, certain specifics of cognitive functions, etc.).

The study was conducted in two stages.

I.. Previously, the subjects were offered two psychodiagnostic methods that focused on the features of the Self-concept.

II. After 5 days, the subjects were shown a movie (on a computer monitor or on a large screen, using a multimedia projector), after which the subjects again underwent the same techniques.

The study involved 39 participants (age-from 17 to 23 years, average age-20.5; gender composition-20 girls, 19 boys).

The distribution of study participants into experimental and control groups was carried out by an experimenter, with approximate alignment by age and gender composition. Social characteristics were also taken into account (characteristics of interests, general level of academic performance). In the experimental group there were 19 participants (10 girls, 9 boys), in the control group — 20 (10 girls, 10 boys). All the subjects were full-time students of the specialty "Psychology", DonGU, mostly senior years — 1st and 2nd years of the master's degree, 4th year of the bachelor's degree, and 4 people of the 2nd and 3rd years of the bachelor's degree; the average age in the experimental and controlgroups approximately coincided. The drug used in the study was not previously seen by the subjects.

Two methods were used to assess the film's impact on the Self-concept.

- V. Stefanson's "Q-sorting" methodСтефансона(adapted by E.L. Gorfinkel and I.L. Keleynikov at V.М. Bekhterev Research Institute). The test consists of 60 questions-statements, with the need to choose the answer "yes / "no". The questions allow you to determine self-assessment based on six main trends of behavior in the group: "dependence", "independence", "sociability", "non — sociability", "acceptance of the struggle", "avoidance of the struggle" (for each trend-10 questions).

- The method "Personal semantic differential" (abbreviated as LSD; modification of the method of Charles Osgood). At the same time, for a deeper analysis of the Self-concept, a distinction was introduced in it between three aspects: the self-real, the Self-ideal, and the Self-anti-ideal (the technique is borrowed from the study of V.S. Sobkin and O.S. Markina [Sobkin, 2008]). In this method, the attitude to oneself is determined by scaling (21 scales) and then summing up the points by three factors:"Strength", "Activity" and "Score". Each of the three aspects of the Self-concept is evaluated separately.

The study used the American adventure comedy film Vacation (2015), directed and written by J. Daley and J. Goldstein. Plot: a young father and an exemplary family man really wants to unite the family and recreate the holidays of his childhood (from the film "Vacation", 1983), where the main character was still a boy). Together with his wife and two sons, he decides to take a trip across the country, heading to one of the best parks in the United States, WalleyWorld. At first, their journey goes smoothly, but the further they get away from home, the more problems arise. However, despite all the difficulties, the head of the family intends to complete his journey.

In statistical data processing Pearson's r-test was used to assess the correlation, and Student's t— test and Wilcoxon's T-test were used to assess the significance of the difference in average indicators.

The study was conducted in 2020, with the participation of V. I. Antropova.

Results and discussion

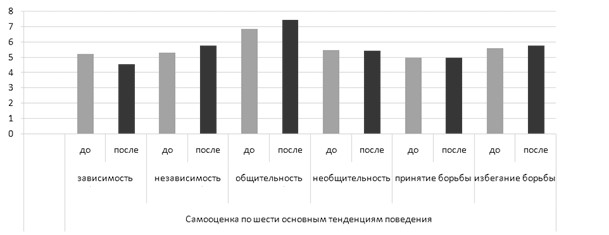

The results of the "Q-sorting" method in the experimental group are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Q-sorting results before and after watching a comedy movie

We obtained a significant change in the average self-assessment indicator for the "Sociability" factor (p ≤ 0,05, according to the Student's criterion; according to the Wilcoxon criterion, the significance of the shift is p ≤ 0,01). Self-esteem for the "Dependency" factor also decreased slightly(p < 0,05) and self-esteem for the "Independence" factor increased (p < 0,05). There were no significant changes in the control group (Figure 3).

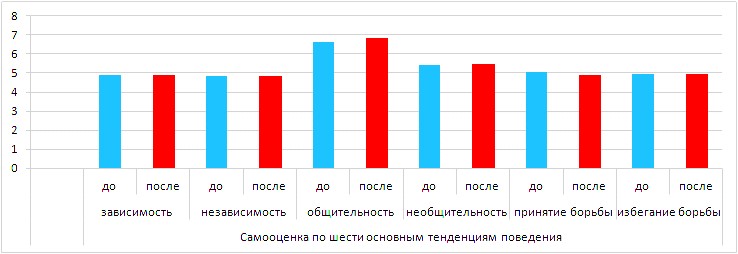

Figure 3. Results of the "Q-sorting" method "before" and "after" (control group)

Comparison of the experimental group with the control group "before", as well as comparison of their" after " did not show significant differences (when comparing the samplest, the Student's t-test was used). Only a certain approximation to the level of "tendency to differ" was revealed in the indicators "Independence" and"Avoidance of struggle""after", both indicators were slightly higher in the experimental group.

The growth of independence and sociability in the experimental group can be seen as an increase in the state of self-confidence in the relationship system, i.e., a state of self-affirmation. Also note that independence and sociability contradict each other to a certain extent: independence puts out of relationships, sociability, on the contrary, includes in relationships. This contradictions removed if we assume that this is a manifestation of the position of the Whistleblower position that just combines both, due to inclusion in the relationship, but with some detachment, as if on the rights of exclusivity.

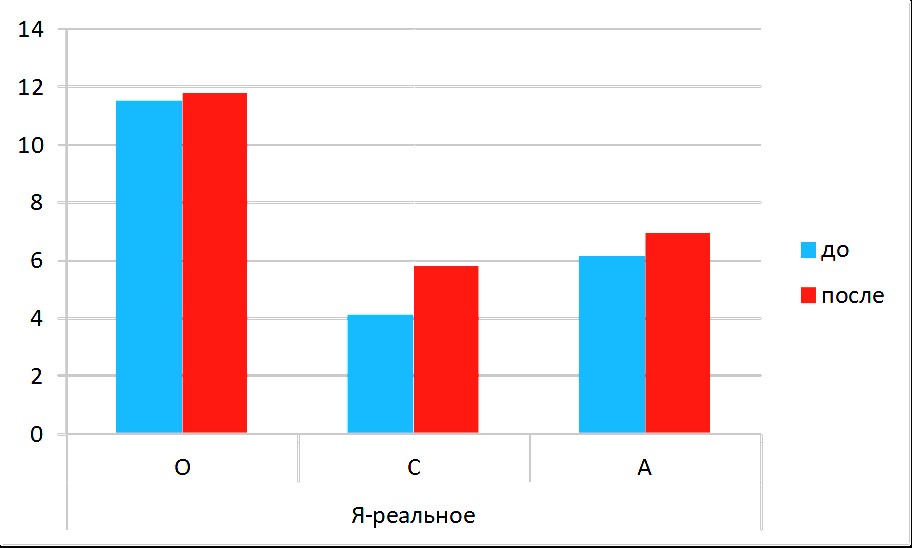

The results of the "Personal semantic Differential" method are presented in Fig. 4—6.

Figure 4. Factors according to the "Personal semantic differential" method before and after watching a comedy film (I-real)

Although growth is observed for all three factors in I-real (Figure 4), it is only for the "Strength" factor that it has reached significance at the trend level (p ≤ 0,08).

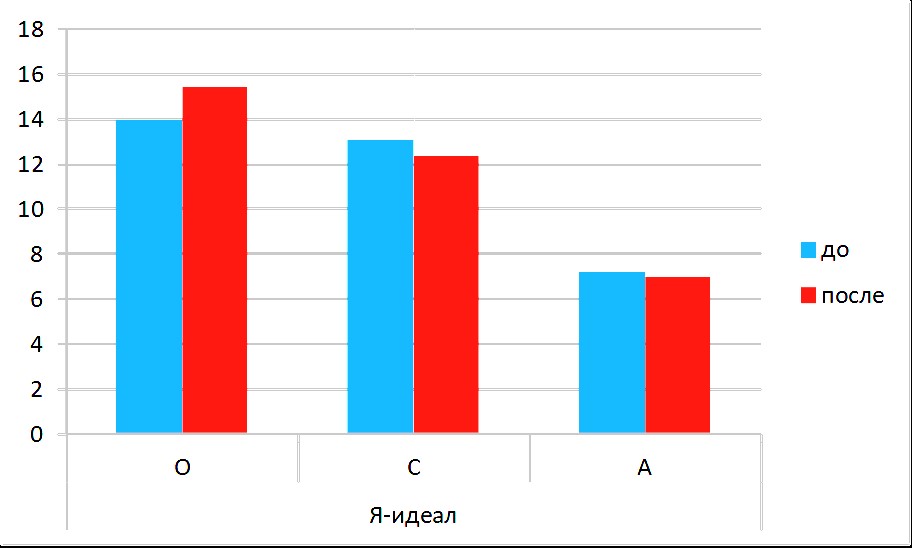

No significant changes were found in the I-ideal (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Factors according to the "Personal semantic differential" method before and after watching a comedy film (I-ideal)

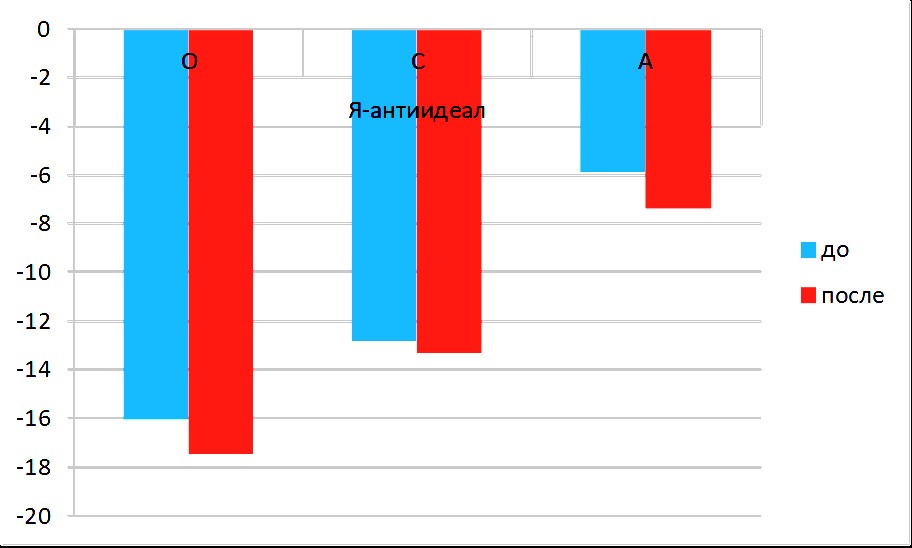

A shift with significance at the trend level (p < 0,08) was observed for the "Score" factor in the anti-ideal (Figure 6).

Fig. 6. Factors according to the "Personal semantic differential" method before and after watching a comedy film (I-anti-ideal)

In the control group, no significant changes were detected (we do not give diagrams; the results "before" and "after" are almost the same).

The tendency to increase the "Strength" factor in the Self-real is an additional confirmation of the appearance of a state of self-affirmation after watching a comedy film. A negative shift in the "Rating" factor in the anti-ideal is a sign that the self-affirmation we are talking about is due to the strengthening of the negative character's attractiveness, as if it were humiliating him.

In this result, we can see the actualization in the consciousness of two polar opposite interrelated images: the self-asserting "Whistleblower "and the humiliated "Fool".

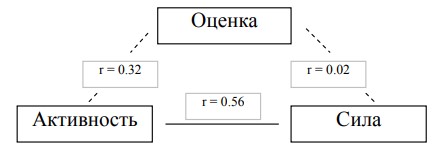

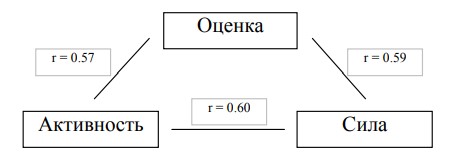

Changes incorrelations between factors are of interest as an additional material (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7. Correlations of factors according to the method of "Personal semantic differential" before watching a comedy film (I-real)

Figure 8. Correlationsof factors according to the "Personal semantic differential" method after watching a comedy film (I-real)

After watching the film, there were correlations between the indicators for the y factorу "Score" and the indicators for the factors "Activity" and "Strength" (rgr = 0,46 at p ≤ 0,05). So, a positive attitude towards yourself after the film began to correlate with the experience of your strength, self-confidence. Obviously, this also indicates that the film is recreating a state of self-affirmation.

In other I-concentration modalities (I-ideal and anti-ideal), viewing the film had an effect in one case: in the anti-ideal, there is a correlation between the "Score" and "Strength" factors (before: r =-0,16, after: r = 0,56; in both cases, at p ≤ 0,05): the more negative the image is anti-ideal, the weaker and more vulnerable it is. In our opinion, this is an additional evidence of the specifics of the self-affirmation created by the film — it is based on the humiliation of a negative character.

Another shift towards the appearance of correlation: the indicators for the "Score" factor in the I-real and I-ideal began to correlate after watching the film (before: r = 0,29; after: r = 0,62; in both cases at p ≤ 0,05). This should probably be interpreted as a shift towards "idealizing" yourself after watching a comedy.

Thus, watching a comedy film creates a shift in the viewer's Self-concept towards self-idealization, increasing confidence and awareness of their own strength, while at the same time belittling the image of the anti-ideal. We believe that this effect occurs on the basis of introducing the viewer to the position of the "Whistleblower", whose self-affirmation is realized by humiliating the subjects opposing the "Whistleblower" (introducing them to the image of"Fools").

Our results indirectly confirm the possibility of comedies structuring the audience's cognitive sphere in the "projection space" format, as we described above. The point is that self-affirmation as a way of realizing self-consciousness is congruent to the projection space. Thus, self-consciousness, formatted according to the structure of the projection space, presupposes the active identification and autonomization of such an aspect of self-consciousness, as I-for-others. The projection of the I-I-for-others, becoming as it were an independent entity, does not so much express the I-real as it is used as a constructed tool for influencing others, acquiring power over others — the very "aiming" that, according to Piaget, generates projection space. In this sense, the assumed projection space explains well the cognitive basis on which self-affirmation appears.

This is also important for understanding the possible impact of comedy on the state of the viewer's cognitive sphere. Projections themselves are compatible in any way (they can overlap or combine without interacting), so in the world of projections, logic as such is not needed and is replaced by imagination[Adler, 1997] (actions with images). The projection world itself is incoherent. It can have simulated connectivity. This means, that the cognitive functions that are responsible for the coherence of consciousness — attention, memory, and retribution — do not play a key role here. This is probably, why comedy had the most negative impact on memory and attention in our study of the impact of different genres on cognitive functions [Yanovsky, 2017a]. The projected world does not reflect reality, but is, as it were, adapted to the needs of the subject who creates it; this world is ego-centered. Therefore, self-affirmation in it occurs naturally.

Of course, at this stage, the stage of testing, we can only talk about preliminary conclusions. However, the study provides grounds for problematization of the question of the psychological impact of comedy. It also confirms that the effects of cinema on the viewer cannot be reduced to evoking emotional reactions, or transforming the viewer's self-image by simply identifying with certain characters in the film.

Conclusions

- Theoretical analysis and generalization of various concepts of the comic as a phenomenon makes it possible to form an integrative model of the parameters of the image of the world recreated by the comic and, as canbe assumed, implemented as the film world of comedy.

- The world of comedy is: a) a world of inter-subjective competitive relations; b) a world with produced inequality in relations; c) a world of disguises and exposures; d) a world in which the system of relations constantly fluctuates between the violation of equilibrium and its restoration.

- There are reasons to compare the structure of the film world of comedy with the structure of the" projection space "as understood by J. Piaget (according to Piaget," projection space " is a form of representation of the structure of space inherent in one of the phases of the development of egocentric consciousness).

- "Entering" the film as a "projection space", we can assume, gives the viewer the opportunity to take the position of a subject-a judge, a "Whistleblower" who sees the lack of superiority of other subjects behind the "masks" covering them.

- The results obtained in the pilot study provide some confirmation of the described theoretical concept of comedy. Thus, after watching the film, the audience shows signs of experiencing self-affirmation:

- there is a slight increase in self-esteem in such parameters as independence and sociability (the "Q-sorting" method);

- there are correlations of the "Rating" factor with the "Strength" and "Activity" factors in the Self-real (the "Personal semantic Differential" method), as well as the correlation фактора of the "Rating" factor in the Self-real with the "Rating" factor in the Self-ideal;

- in the anti-ideal, there is a correlation between the "Score" and "Strength" factors, which can be interpreted as a tendency to belittle a negative character for self-affirmation.

- Theoretically, it can be assumed that if comedy really gives the viewer an image of the world as a "projection space", then it probably increasesthe importance of imagination as a form of arbitrary work with images, while reducing the importance of their logical coherence.

This research is exploratory and preliminary in nature. Conclusions can be drawn reasonably enough after conducting studieswith varying different basic variables of the film (types of plots and situations, character sets, etc.) and with a large sample size.

[Adler, 1997] Или обманом, что тоже воображение, но с целью имитации реальности для какого-либо адресата. Неслучайно комедия строится на обманах и разоблачениях.