What is this article about?

This article is, in a sense, a continuation of the conversation that I started on the pages of this journal exactly 10 years ago [Veresov, 2014; Veresov, 2015] talking about the method of cultural-historical research known as the experimental-genetic method. The discussion point was how to solve the problem that researchers face, which can be formulated as follows: "How to build an experimental design according to Vygotsky?" or "How to conduct the experimental study so that one can be sure that it is built on the basis of the general principles of the experimental-genetic method?". I proposed five principles for organising and constructing research - what in the Western tradition is called "requirements for the research design".

In this paper, I will try to take the next step and answer the question, which, by the way, I quite often have to hear - "I have conducted research and here are my data, but how to analyse it from the point of view of cultural-historical approach?". Or, in professional terms - "Here is my data...But what exactly to look at? What should I choose to analyse in detail, and how should I analyse it?". This is not an idle question at all. It is surprising that there is still no general approach, no system of requirements (or even just recommendations) on how to analyse experimental data. This leads to some misunderstanding and even confusion since each researcher analyses data as he or she sees fit. And since this is the case, it opens up wide possibilities for subjective and arbitrary interpretations. This is one of the reasons why mainstream psychology is so sceptical of our research. It is really difficult to treat it otherwise, when in cultural-historical research everyone can design the experiment almost as he or she likes, and to analyse the obtained data as well. In this case, there is nothing to say about comparability, if the results of analyses of the obtained data depend not on the data, but on the subjectivity of the researcher and sometimes not only do not correspond to each other but are in direct contradiction.

I, of course, exaggerate the problem on purpose, though not too much. We, scholars of my generation, who grew up on this tradition, know how to design experimental conditions and how to analyse, because we did it together with our teachers, and they knew the experimental-genetic method perfectly well. But what about those young colleagues of ours, especially foreign colleagues, who are only making their first steps? What should they be guided by, how to protect themselves from mistakes and not to slip into superficial interpretation instead of serious and deep analysis, especially since there are plenty of examples of such interpretations. In short, we need some clear tools - working models, frameworks, instructions, matrices - call them what you like, which could help not only to organise the research process correctly, but also to analyse the data obtained. This is what my article is about.

The social environment is the source of development: what's next and how to work with it?

In cultural-historical theory, the social environment is considered not as a factor, but as a source of development of all higher psychological functions[Veresov, 2014]. This idea, which emerged at the early stages of the development of the theory, appearing first in Psychology of Art [Vigotskii, 1935] and in several defectological works from 1925, acquired more and more complete content at different stages of the development of the theory, but generally remained unchangeable.

However, it is one thing to accept this idea as a certain general and even fundamental position, as a certain axiom or a postulate, and another thing to accept it as an idea that leads to the selection of analytical tools, as something that allows us to properly build an experimental study of the developmental process and, what is even more important, gives the researcher the means to analyse the obtained data.

It is impossible to build a specific experimental study on any, even the most brilliant general idea. This requires more specific concepts, which allow to correctly build experimental conditions in a particular study, and which, at the same time, can act as a means of analysis, capable of capturing not only the dynamics of change, but also the essential side of the development process.

In one of my articles [4.. Psikhologiya , 1998] I wrote that we need theoretical means of analysis that allow us to "refocus the researcher's lens on development". To "grasp" the very process of development, its dynamics and psychological content, to explain the changes that occur or do not occur, to move from descriptive to explanatory modes of analysis, that is, to uncover through analysis the inner essence of the phenomenon - this requirement for the scientific method was essential for Vygotsky and he repeatedly returned to this theme. It is not surprising that in Vygotsky's works we can see how this general idea was gradually filled with concrete content, how on this basis he and his collaborators gradually built up a system of concrete psychological concepts as tools for analysing the process of development.

In this article, based on Vygotsky's work, I want to show: 1) how the general idea of social environment as a source of development can be conceptualised in two concepts - the concept of "social situation" and the concept of "social situation of development" and 2) how an analytical model created on this basis can become a concrete tool for analysing the experimental data.

Social environment, social situation and social situation of development - a cultural-historical analytical model

The concept of social situation of development and the related concept of perezhivanie appeared in a series of works related to the last period of Vygotsky’s work - these are on pedology from 1930-1933 as well as the book The Problem of Age [Vygotskii, 1986; Vygotskii, 2001], which remained unpublished in its entirety.

Let us begin with the social situation of development. This concept was precisely and definitely developed in connection with the problem of age development as a criterion for determining the psychological age. Following dialectical logic, Vygotsky, distinguishing two phases in each psychological age - critical (crisis) and lytic (calm), and attributes the critical phase to the beginning of psychological age. It is here the concept of social situation of development is first formulated [Vygotskii, 2001, p.25].

Revealing the content of this concept, Vygotsky emphasises the following essential aspects.

First, the social situation of development is "completely original, exclusive, unique, and unrepeatable relationship between the child and the environment" [Vygotskii, 2001, p.43]. Let us note that it is not seen as "the relation of the child to social reality", but between the child and social reality. Here we do not deal with a mere figure of speech or carelessness - the "relation between" implies, by definition, both the relation of the child to the social environment and the relation of the environment to the child. Here the child is not opposed to the environment, but " embedded" into it.

Second, the social situation of development is " is the starting point for all of the dynamic changes occurring in development during a given period" [Vygotskii, 2001, p.43]. That is, in other words, it is the initial moment of all changes in the course of development throughout the entire psychological age, not just the phase of crisis.

Thirdly, " It determines wholly and entirely the forms and the path by following which the child acquires newer and newer properties of his personality, drawing them from the environment as the main source of his own development, the path by which the social becomes the individual " [Vygotskii, 2001, p.43]. Here we see a clear reference to the fundamental idea of social environment as a source of development.

But not only this! The child acquires new properties, the child develops, but it does so scooping (черпает in Russian) its new features from social reality. It seems that this is not an accidental beautiful expression, but an important clarification of the very concept of social environment as a source. Until a child starts "scooping" from this social environment, from social reality, it remains only a potential source of development. It can be compared to a source of water - a well, a river or a lake, or just water in the tap, remain only potential sources, but they become real, real (oh, it is not for nothing that Lev Semyonovich says not about social environment, but about social reality!) sources only when someone starts to use them as a source - with the help of a scoop, bucket, glass, etc.

Fourthly, the social situation of development is a concept that relates not to the structural but to the dynamic aspects of psychological age, that is, it is an analytical tool that allows explaining the dynamic changes in the process of age development and therefore, it goes together with the requirement for analysis - " In this way, the first question which we must address in studying the dynamics of any age consists of clarifying the social situation of development" [Vygotskii, 2001, p.43]. Having arisen at the beginning of the age period, in the first phase, in the phase of crisis, it persists throughout the age, but due to the fact that the child develops, “it with an inner necessity determines the annihilation of the social situation of development, the end of an epoch of development and a transition to the subsequent, or higher, age stage” [6, pp. 44-45].

Thus, the emergence of psychological neoformations in the child, the gradual disintegration of the former social situation of development and the gradual formation of a new unique system of relations between the child and social reality - this is what is called the dynamics of age development. In other words, for a full-fledged study of the child's development, it is not enough only to find out (and describe) the initial social situation of development at the initial stage of age and to investigate the process of the emergence of neoformations, the analysis should include the related processes of the disintegration of the old social situation of development and the gradual emergence of a new one during the whole psychological age.

Let us focus our attention at three points that are important for the further presentation. The concept of "social situation of development" introduced by Vygotsky at the last stage of his work is a concretisation of the general idea of social environment as a source of development. This concept can be used as a tool of analysis, i.e. with the help of this concept it is possible in a concrete experimental study to precisely define the subject of research - to describe the initial social situation of development, to study by experimental means the processes of gradual disintegration of the existing situation and gradual emergence of a new one in connection with the emergence of psychological neoformations in the child.

At the same time, the concept of "social situation of development" is strongly "tied" to the concepts of psychological age and the critical period of age, for it appears "at the beginning of each given age period" [Vygotskii, 2001, p.43]. Finally, the social situation of development is the relationship between the child and social reality (not the child's relation to the social environment), where he or she acts as a participant, an active side, with his or her active attitude and participation in it. In other words, it is not in itself, not by the very fact of its presence, but by being embodied in specific social situations of development that the social environment begins to play its role as a actual source of development, turning from a potential source into an real one, it only then begins to act in this role, becoming what Vygotsky accurately called "the social reality".

But this was not enough! For even then, the general framework of the case study, the theoretical framework remains very general and therefore vague. It seems to me that this is why, in Lectures on Pedology [Vygotskii, 1986], delivered a few months before his death, Vygotsky revisits the concept of social situation of development. He makes the next step in concretising the general idea of social environment as a source of development. The basis for this was experimental data and clinical observations. In his lecture "The Problem of Environment in Pedology" he gives several examples of such clinical observations and, which is important for the topic I discuss in this paper, gives examples of analyses of some of these clinical cases.

The example of three children with an aggressive alcoholic mother [5, pp.70-71] has already become a classic and has been reproduced many times in the literature, so in order to save space I will not dwell on it in detail. But it is necessary to dwell on how Vygotsky analyses this situation and what concepts he uses here as analytical tools to make the analysis not descriptive but explanatory.

So, a drinking and aggressive mother and three children showing three different "pictures of developmental" in this situation, to use Vygotsky's own words. Here we find not so much a description of the situation itself (it is given in a concise, lapidary form), but an analysis of it from the point of view of the influence of the environment on the development of children. This analysis begins with the question: "What determines the fact that the same environmental conditions have three different effects on three different children?" [Vygotskii, 1986, p. 71]. And the answer is: “This is due to the fact that the attitude of each of these children to an event is different. Or, as we might say, each of these children has undergone the experience of this situation differently” [Vygotskii, 1986, p. 71]. The word “experience” (переживать in Russian), should not confuse the reader as the following sentence explains the point: “And so, depending on the three different perezhivaniya of one and the same situation, the impact that the situation has upon their development turns out to be different” [Vygotskii, 1986, p. 71]

Let us pause for a moment and note that here Vygotsky not only introduces a new concept of perezhivanie into the explanation but says that perezhivanie (and perezhivaniya as plural form) is an attitude to certain event. This has direct relevance to another work - namely the chapter "The Crisis of 7 Years" in the book The Problem of Age, on which Vygotsky was then working at that time. In that chapter he says that "perezhivanie must be understood as the child's inner attitude as a human being to this or that moment of reality" [Vygotskii, 1983, p.382]. Sadly, an unfortunate error in the English translation, where “internal attitude” was translated as “external relation” [Vygotskii, 1984, p. 294] makes the understanding almost unattainable for the English-speaking reader[Veresov, 2015].

Here the sophisticated reader may ask a question – did not this concept appear earlier in the Problem of Age, when Vygotsky discusses the critical periods of psychological age, and did not he say in this work that " A meticulous study of the critical age demonstrates that in them there occurs a basic alteration in the perezhivanie of the child"[Vigotskii, 1935] [Vygotskii, 1983, p. 383]? However, we note that in this Volume of the Collected Works the word "perezhivanie" is used 169 times and in very broad and different contexts, but this does not give us reason to believe that it was in this work that the concept of "perezhivanie" itself was introduced without being rigidly tied to age crises.

This is why the lectures on paedology are of interest to us, because here the concept of perezhivanie is given precisely without such a rigid link. He says that the impact of the situation on the course of development of each child depended on the fact the three children had three different perezhivanie of the same situation.

Let us note; firstly, in this analysis Vygotsky is saying that these three children are in the same (literally "one and the same") situation and, secondly, that the effect it had on their development (not on the children, but on their development!) depended on the fact that three different perezhivaniya arose in this situation.

In other words, Vygotsky is not talking about a "social situation of development" as a synonym to the social situation. His analysis goes deeper, he says that in some social situation, due to the fact that it refracted through each child's individual perezhivanie, three different social situations of development arose, which led to three different pictures of development. That is, between the social environment (as a source of development) and the social situation of development there appears another important concept - "social situation", i.e. an event in which the child is involved not only emotionally, and to which he or she has a specific internal attitude. The social situation, refracted through the prism of perezhivanie as an internal attitude, may or may not lead to the emergence of a social situation of development.

Hence it becomes clear that the social environment always appears in the form of some specific social situation as a "part of the environment" [Vygotskii, 1986, p. 69] and only its refraction through the prism of the child's individual perezhivanie leads to the emergence of a "social situation of development", i.e. exactly what Vygotsky defined as "a completely original, exclusive, unique, and unrepeatable relationship between the child and the environment" [6, p.43). There is no doubt that "perezhivanie is determinative in terms of how a particular moment in the environment affects a child's development" and that "the environment determines the child's development through the perezhivanie of the environment" [Vygotskii, 1983, p. 383].

But in the Lectures on Pedology this position is concretised and developed - the social environment becomes (or does not become) a valid, real source of development (the social reality) only when: 1) there is a certain concrete social situation and 2) this situation is refracted through the prism of perezhivanie, which leads (or does not lead) to the emergence of a social situation of development. And it is here, in this text, that Vygotsky actually substantiates the perezhivanie as a concept - "... perezhivanie is a concept that allows us to study the role and influence of the environment upon the psychological development of the child in the analysis of the laws of the development” [Vygotskii, 2001, p. 72]. In other words, perezhivanie is a concept, i.e. a theoretical tool for analysing the role and influence of the social environment not on the child, but precisely on his/her psychological development.

Elsewhere [9; 10;11] I have given a detailed description analysis of the concept of perezhivanie and social situation of development, so I will not repeat myself and return to the topic of the article. Is it possible to design, based on these ideas of Vygotsky, a tool that would allow the researcher to analyse the data obtained? Is it possible to build a general analytical model that will allow not only to describe, but also to analyse and explain the observed changes in the child's development in the data? It seems to be quite possible. This model (cultural-historical genetic-analytical model) was first presented in my paper [Ma, 2022] and is already used to build research programmes and analyse experimental data [Rogoff, 1995], so here I will only give a general and brief description.

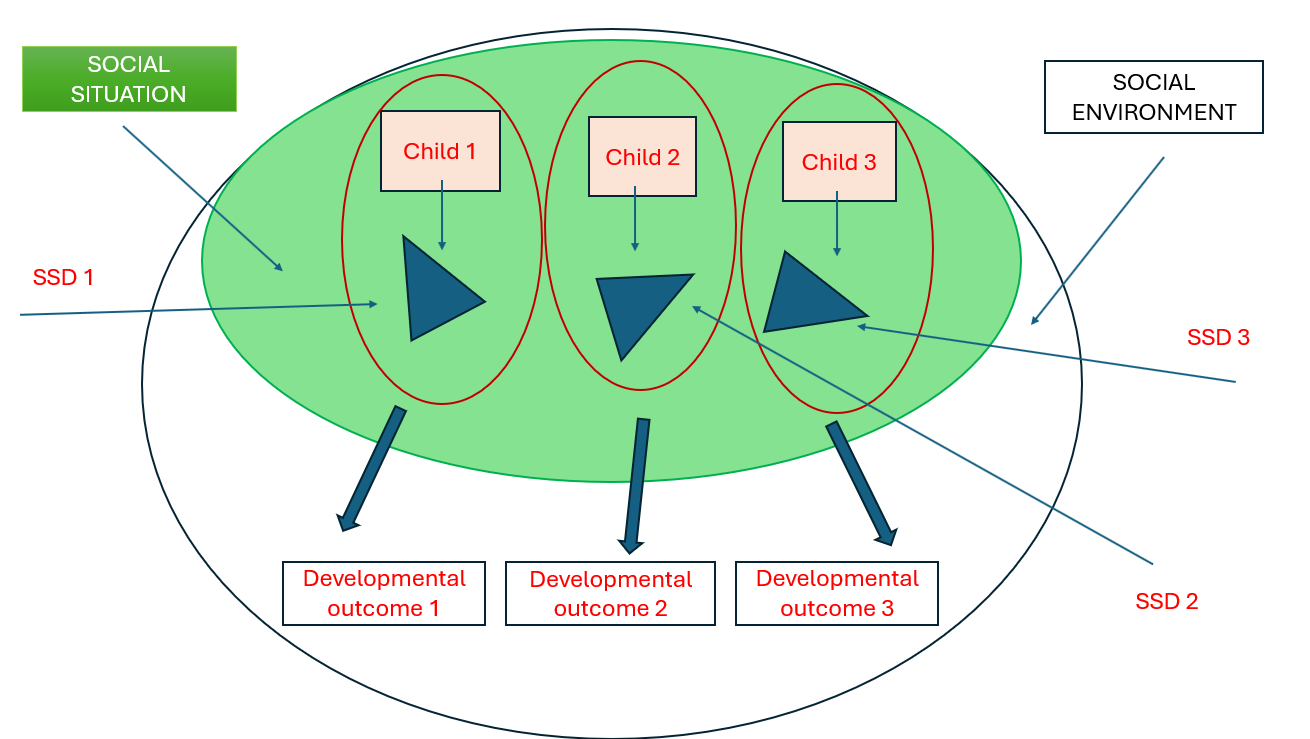

Cultural-historical genetic-analytical model (Figure 1) is based on the example of the analysis from Vygotsky's work I presented above and includes the social environment (the big white sphere), the social situation (the green sphere), three refracting prisms (blue triangles), three social situations of development (the spheres outlined in red - SSD1, SSD2, SSD3) and three "developmental pictures" (Vygotsky's words), i.e. those changes that took place in the child's development (developmental outcomes 1, 2 and 3).

Figure 1: Cultural-historical genetic-analytical model (Veresov, 2019, Veresov et al, 2024)

Social environment in the broad sense is a set of objectively existing socio-cultural conditions and contexts in which a child develops - family, educational, play, etc., and which influence his/her development, but only potentially.

A social situation is "a part of the social environment" (Vygotsky's words [Vygotskii, 1986, p.69]), represented as an event in which the child is involved as an active participant, in which what Vygotsky called the "social plane" where psychological functions appear (or do not appear) in their "inter-psychological” from. It is in the social situation that the cultural means of development - signs - appear as mediating components of the social plane and inter-psychological forms. What is extremely important, the social situation is not static, it has its own dynamics, it is constantly changing and therefore the social plane of development can arise, disappear, and arise again depending on how the social situation unfolds.

The social situation of development arises (or does not arise) within the social situation as a result of the child's perezhivanie of certain moments of the social situation through which it is refracted. Through the analysis of the child's individual perezhivanie of the social situation, which can create different social situations of development, it becomes possible to identify and analyse changes in development, if they occur, and if they do not occur, it becomes possible to explain why. This is where the social environment begins to “work” as a real source of development.

Thus, the proposed model is analytical because it allows us to not only describe but also analyse (using concepts as analytical tools) the process of development in specific conditions in the process of data analysis, and it is genetic because it allows us to analyse the process of development from the point of view of its dynamics and results, i.e. changes that occurred (or did not occur) in the process of unfolding the social situation. In other words, this model allows not only to record changes in the child's development, but also to explain why they occurred and also to explain why these changes ("new picture of development") look like this and not otherwise.

However, even with these advantages, this model remains a rather general framework. The question of how to analyse the available experimental or empirical data, where to start, what are the steps of analysis, in other words, the question "What exactly and in what order to look at the obtained data?" requires further specification. The model should be supplemented with something in the form of an instruction manual, where each step is described. The matrix of cultural-historical analysis, which will be discussed in the next section, might be considered as such an instruction.

How to analyse? From the model to the matrix

The genetic-analytical model is a general frame of analysis that allows us to see how, in what way, some social situation is constructed and unfolds at the macro- or micro-level and in which developmental changes occur (or do not occur). However, I should repeat, in a concrete experimental study, the identification of an individual developmental trajectory requires more precise tools. The developmental conditions and developmental potential of each social situation are unique, and this is the most essential characteristic of any social situation. On the other hand, in the study where the process of development is a process under study, the main goal of a researcher is not only to describe the changes, but also to explain them, i.e. to discover in their manifestation the internal mechanisms of development that obey universal laws. Thus, for the analysis to be both dialectical and genetic, uniqueness and universality must be present in the analysis at the same time.

The genetic-analytical model allows the aspect of generality to be captured in the analysis. The matrix that will be discussed below is based on this model (and therefore retains its generality), but can be used to analyse a particular social situation in terms of the specific conditions in which this generality is manifested.

This matrix has been developed and already used in a few studies [Rogoff, 1995], so here I will limit myself to a brief description. The matrix is a detailed description of all the steps in analysing the available data. It allows the data analysis to be structured according to the basic requirements for cultural-historical method. Firstly, the use of the matrix allows to identify the uniqueness of the analysed social situation in terms of its origin (pre-history) and background, actors, cultural means of development and internal dynamics. The second aspect of the analysis is to reveal the developmental potential of the social situation by analysing the moments of emergence and disappearance of the social plane of development and the corresponding inter-psychological forms of higher psychological functions in this situation. The third aspect is to analyse which aspects of a given social situation were refracted through the child's perezhivanie and whether or not a social situation of development and the corresponding intra-psychological forms emerge as an outcome to which this social situation leads.

Step 1: Analysis of the structure of the social situation

The analysis begins with the identification of the social situation in the analysed data. The uniqueness of this analysed social situation is revealed through two aspects - structure and dynamics. The unique structure of a social situation includes: 1) the background and pre-history, 2) the actors (participants), 3) the task 4) the cultural means included in this social situation and 5) the identification of the initial stage of the social situation. Each of these aspects of analysis is discussed below.

1. Background (origin) and pre-history

The background and the origin of a social situation is a very important component of its structure, because each child in a given situation already has his or her own developmental history (related to age, social conditions, etc.). At each age, the child has a unique combination of already developed higher psychological functions (which Vygotsky metaphorically called "fruits of development" [Veresov, 2014a, p.42] and simultaneously those psychological functions that are not yet developed but are in the process of intensive development, and functions that are just beginning to develop (developmental buds or flowers of development). In the analysis, prehistory cannot be excluded from the structure of the analysed social situation. At the same time, the analysed social situation can be influenced by events that took place immediately before it and with which it is connected; for example, the social situation at the end of a lesson when the teacher asks children to answer questions using their knowledge gained during the lesson. The lesson that has just taken place is the background to the social situation without which the analysis would be superficial and incomplete.

2. Participants

Participants are those who are involved in verbal and non-verbal interactions in a given social situation. In addition, a researcher who is observing or filming, and therefore present, can also be considered a participant in a given social situation. In addition, even people who are not personally present in the situation are considered participants (e.g. when two participants in an event tell a story to people who are absent, using audio or video recording as a tool).

3. A task (tasks)

This is what all interactions between participants are built around. In cultural-historical theory, the task (and the means of solving it) is part of the structure of any cultural form of behaviour (both collective and individual). A social situation may include one or more tasks. As part of the unique structure of a social situation, tasks can be general, set from the beginning (a shared story, reading a book, or playing a game), or they can arise in the course of a social situation (e.g., in class, a teacher asks a student to first count the number of words in a sentence before beginning to write it).

4. Cultural tools for development

The use of cultural tools by participants is an important component of the structure of a social situation. In the analysis, the cultural tools are not the focus of the analysis per se, rather the focus is on how they are used by the participants in their interactions. As already mentioned, they may be used collectively or the child may use them independently, and they may be external tools (signs or sign systems) or internal psychological tools.

5. The initial stage of a social situation

After identifying the structure of the social situation, the next task of the researcher is to identify the initial stage (beginning) of the situation. The general genetic law of cultural development states that every higher psychological function appears on the stage first in the social plane. In other words, the social plane, the inter-psychological plane of existence of any higher psychological function, its appearance not in social relations, but precisely as a specific social relation (when the higher psychological function exists as shared between people) is genetically the first form of its existence. The researcher cannot know in advance, of course, whether this inter-psychological form will emerge in a given social situation, but the emergence of a social plane of development is the most important condition and prerequisite for its emergence. Therefore, the initial stage of the unfolding of a social situation is the moment when the social plane of development first appears and, accordingly, all the components of the structure of a given social situation identified at the first step of the analysis begin to function.

Step 2: Analysis of the dynamics of the social situation

The dynamics of the unfolding of a social situation manifests itself, in particular, in who takes the initiative in the interactions, how this initiative passes from one participant to another, how tasks change in the course of the unfolding of the social situation, what turning points and clashes arise in the process - in other words, all those aspects that lead to changes in the interactions of participants. On this basis, the temporal dynamic parts of a social situation are singled out for separate detailed analysis, and each of them is analysed separately, but also in its relation to the development of the social situation as a whole.

The analysis of dynamics begins after the defining the starting point (the initial stage of the social situation), i.e. the point at which the task appears and the interaction begins, and which I mentioned above. It is in dynamics that the internal processes of development manifest themselves. Therefore, the analysis of dynamics is not limited to the fixation of external changes, but the focus is an analysis of the psychological changes occurring in the child in the unfolding social situation.

For this purpose, analytical tools (means of analysis) are used which are the concepts of: 1) social and individual planes of development 2) inter- and intra-psychological forms of higher psychological functions 3) social situation of development 4) perezhivanie 5) zone of proximal development. At the same time, other concepts such as sign (sign mediation), ideal and real forms, etc. can be used here - depending on what aspect of the process of development the researcher is interested in.

As I have already said, the role and place of the social situation is that it is in the form of a specific and unique social situation that the social environment can become a real source of development. However, the mere existence of a social situation does not tell us anything about how development occurs in the process of its unfolding, or whether it occurs at all. A social situation can become a source of development when a social plane of development appears in it. The social plane of development is an integral part of the process of development, the first form of development of psychological functions (inter-psychological form), which can later become an internal individual-psychological process (individual plane of development or intra-psychological form) in accordance with the general genetic law of development of higher psychological functions [Vygotsky, 2021]. Therefore, in the analysis it is very important to reveal the moments of appearance of social planes of development in the course of its unfolding, i.e. such social interactions, where the higher psychological function appears in a form divided between people - i.e. in its inter-psychological form. The simplest example is the joint thinking of an adult and a child, where the function of thinking is divided and exists in the external (social) plane as an inter-psychological form of thinking.

The identification of such forms in the course of analysis allows us to draw a conclusion about the extent to which the conditions for development exist in a given social situation and what the developmental potential of this social situation is. However, the mere presence of inter-psychological forms does not mean that the process of development takes place. This condition is necessary, but not sufficient. The developmental potential of a social situation, which can be determined by the presence of inter-psychological forms and a social plane of development, may remain unrealised. After all, the social situation itself, even if it has a significant developmental potential, is not yet a real source of development. A social situation becomes a source of development only when a social situation of development (or several) arises within a social situation.

Development, “ingrowing” (вращивание), the transition from outside inwards, from inter-psychological to intra-psychological forms, depends on whether or not a social situation of development has arisen in which, and only in which, this transition is possible. And the emergence of the social situation of development depends on what aspects of the social situation are refracted through the child's individual perezhivanie and how this refraction takes place. Only those aspects of the social situation that are refracted in the child's perezhivanie can become (or not) the basis for the emergence of an individual plane of development. Therefore, even the most favourable social conditions and factors may not lead to development if they are not refracted through the prism of perezhivanie as an integral internal attitude to the social situation. The child, by virtue of his or her perezhivanie, creates and defines his or her own unique developmental trajectory, becoming the subject of his or her own development, often without even realising it. Therefore, in the analysed data it is extremely important to identify those moments in which there are manifestations of the child's individual perezhivaniya, which, of course, exist in various forms. However, here it is very important to proceed from the definition of perezhivanie – perezhivanie is " how the child is aware of, interprets and affectively relates to a certain event." [Vygotskii, 1986, p. 71]. Any (direct or indirect) manifestations of the child's perezhivanie in the data must be identified and analysed, because only through this can the researcher draw conclusions about the presence (or absence) of a social situation of development in the social situation being analysed.

In this regard, it seems important to refer to the concept of dramatic perezhivanie [Ma, 2022] as special kind of perezhivanie refracting contradictory aspects of a social situation (it can be a dispute, clash of positions, desires and motives). I note in this connection that the situation in Vygotsky's example of the social situation of the three children and their perezhivanie are examples of a dramatic situation and dramatic perezhivanie. Attentive readers may object to this: in the example of analysing the situation of three children, Vygotsky says that as a result of three different perezhivanie, three different "pictures of development" emerged in the three children, but all of them, according to Vygotsky, are pictures of disruptive development. Does this mean that in a dramatic social situation the perezhivanie does not so much support development as destroy its normal course? The point, however, is that the concept of dramatic perezhivanie refers to the dynamic aspect of a social situation. This means that not only the perezhivanie, not only the drama, but also the way in which the child overcomes the drama is the psychological essence of the concept of dramatic perezhivanie. And in this sense, the role of the adult who, by offering cultural means, helps the child to overcome difficulties or challenges becomes extremely important. To clarify this, we conducted a special study [Veresov, 2016] in which we showed that dramatic moments can be developmentally dangerous, but if managed accordingly, they become opportunities.

The child's dramatic perezhivanie and the way the child overcomes dramatic moments and collisions can be interpreted as turning points, key moments in the child's development within the analysed social situation. In other words, the child's dramatic perezhivanie and the refraction of collisions and dramatic moments in the unfolding of the social situation are the most reliable criteria for making a conclusion about the presence or absence of a social situation of development. If there are no dramatic moments, collisions, conflicts of positions or motives in the analysed social situation, or if they are not refracted in any way in the child's consciousness and do not manifest themselves in the form of a specific attitude towards them, then this is evidence that there is no social situation of development and that the developmental potential of the social situation remains unrealised even in the presence of a social plane and inter-psychological forms.

Step 3: Developmental outcomes

The final step of the analysis according to the matrix is to analyse the developmental outcomes in a given social situation, that is, to identify and analyse the changes in the child's development that have or have not occurred. From the perspective of cultural-historical analysis, not all changes in activity and interactions are understood as development. The essence and direction of the analysis is to identify the most significant moments that determine the changes in the social situation that create the conditions for development.

Such moments can be: 1) a contradiction (manifested as a clash of positions, motives, etc. in the form of a "small drama" [Veresov, 2017, p. 59] or 2) a child's transition to a new qualitative level (for example, transition from unmediated to mediated actions), 3) transition from collective forms of cultural behaviour and activity to individual ones, or 4) transition from using external signs to using them as internal means of organising behaviour and activity. In addition, a child's movement in the zone of proximal development, when the level of potential development becomes the level of actual development, should also be regarded as an act of development. If such changes in development (or changes leading to development) occur in a social situation, then we can say that the developmental potential of the social situation of development has been realised. However, the potential may remain unrealised, because the conditions for the realisation of the potential are the emergence of the social situation of development, the social plane of development, the presence of an inter-psychological forms. That is why these aspects are the most important to analyse using the matrix as a tool.

In conclusion

I believe the use of the matrix as a tool of analysis allows to solve the main task and corresponds to the main requirement to the analysis mentioned by Vygotsky - to focus the analysis not on the description of existing forms and phenomena in the data, but to reveal the internal processes of development manifested in these phenomena. Its use makes it possible to identify the most significant moments of development and thereby explain these data as manifestations of a process of developmental hidden from direct observation. But what makes this change of the focus possible?

Explanation becomes possible through the use of a system of concepts that reveal the most important aspects of development. Unlike other analytical models [Veresov, 2019; Vygotsky, 1998] the concepts are not taken singly, but in a holistic relationship. This minimises the possibility of subjective interpretations.

For example, in the study of ZPD, the child's transition to the level of actual development can be judged only through analysing changes in all the dynamic components of the social situation - Did the social plane and the corresponding inter-psychological form emerge at the beginning of the given social situation? Did the unfolding of the social situation have a dramatic contradiction (intellectual collision, etc.) and was it refracted in the child's individual consciousness? Did this bring a new social situation of development and the disintegration of the previous one? Has an individualised developmental plane and corresponding intra-psychological form emerged as a result? Has there been a transition (vraschivanie), i.e. have external means/signs become internal psychological means? Only if all these components are present can we say that the child has moved to a new level of development in the ZPD. In all other cases we can only talk about some progress of the child movement within ZPD.

The matrix is not only for analysing the data that have already been obtained. It can also serve as a tool for the research design. This is especially important in the genetic (formative) experiment, the essence of which is the creation of experimental conditions in which it becomes possible to elicit and follow the process of development itself. This is what Vygotsky drew attention to when he wrote that the essence of the experimental-genetic method is that it " it artificially elicits and creates a genetic process of mental development” (1997, p. 68). The matrix can help the researcher to set up the proper experimental conditions that should produce the expected result. If development does not occur, the matrix allows us to explain this, for example, by the fact that there is no social plane (and the corresponding inter-psychological form) in the given social situation, or because the social situation of development did not arise and therefore no individual intra-psychological form appeared, or because the dramatic moments of the social situation were not present or were not refracted in the child's perezhivanie. In other words, if significant developmental changes do not occur, the matrix makes it possible to explain why this did not happen consequently, how the experimental conditions can be changed.

I am aware of the reactions this analytical matrix might provoke in the contemporary cultural-historical/activity community. Any departure from the charming activity reductionism is seen by some as heresy and an attack on the sacred foundations, confusing unformed minds. However, I hope that going back to the foundations (i.e., directly to Vygotsky's ideas) and developing them on this basis, which is the basis of the analytical matrix, may serve as some justification here. The experience of using this matrix in specific studies has already shown its effectiveness, and I hope that it will enrich the arsenal of tools of cultural-historical analysis and help young researchers in mastering the experimental-genetic method, and cultural-historical theory in general. Well, I will simply repeat the words I said ten years ago: I sincerely wish this daredevil success. And, of course, I am ready to help in any way I can.

[Veresov, 2014] I prefer “psychological”, not “mental” as it was translated in the English Collected Works.

[Veresov, 2015] In our translation [Vygotskii, 2001] we have corrected this unfortunate error (as well as many others). And in general, this translation of The Problem of Age is the only and most complete translation to date, because only separate chapters have been published in Russian and in different sources. As translators and commentators, we have taken the liberty of combining all the chapters under one cover, although we made it clear in the preface and introductory chapter.

[Vigotskii, 1935] The English translation says: “Careful study of the critical age levels shows that changes in the child's basic experiences occur in them” [Vygotskii, 1984, p. 295]. In our translation [Vygotskii, 2001, p.239] we have corrected this oversight.