COMMUNITY MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES IN GREECE: DEVELOPMENT, CHALLENGES AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Greece’s shift from asylum-based to community-based mental health services began after joining the European Union (EU) in 1981. Specifically, the adoption of the European Council’s decision 815/84 made provisions for urgent financial support to facilitate the psychiatric reform of the Greek mental health care system. In order to support the reform effort beyond that initial EU funding, in 1995 the Greek government implemented a long-term operational plan called “Psychargos”, which was initially jointly funded by the EU, and eventually funded entirely with national funds (data obtained from the official “Psychargos” website). The name “Psychargos” originates from the mythological “Argos” and the return of the golden fleece, symbolizing the safe return of patients with mental disorders back to the community. The original “Psychargos” package ran from 2000 and has been renewed twice to this day. The most recent (third) “Psychargos” (2010–2020) package had three distinct linchpins, including, firstly, the programing of actions to promote community-based services, and secondly, the design of educational actions to promote the mental health of the general public and to prevent mental illness at a primary and a secondary level, for instance, in substance use disorders. Lastly, the package included actions to organize existent mental health services and to inform and train their workforce. The mental health service reform is ongoing.1

Service development plans

In 2011, an ex post evaluation of the progress of psychiatric reform was performed in collaboration with King’s College London and the UK National Health Service, led by Professor Nikandros Bouras.2 The research methodology comprised both qualitative and quantitative approaches based on multiple research methods. The primary data sources included individual interviews, focus groups (with both mental health workers and patients and patients’ relatives), site visits and specially devised questionnaires. The secondary data sources included literature reviews, reports and official documents. The evaluation provided valuable insight into existing infrastructure and services, and highlighted several fundamental challenges, including organizational shortcomings. We refer the reader to the article for a more extensive presentation of the evaluation methodology. Following the economic crisis that ensued, in 2019 the Ministry of Health and Social Solidarity laid out a blueprint for the development of new services to support the further growth of community-based mental health care in the country. This ambitious plan put emphasis on the development of many new services in the community, such as mobile units, day hospitals and community mental health teams, and had an overall positive impact. Recently, the Ministry produced a national action plan for health for 2021–2025, which includes a set of generic goals, including preventive and public health targets. In regard to mental health, the emphasis was put on child and adolescent psychiatry and substance and alcohol misuse.

COMMUNITY MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES IN GREECE

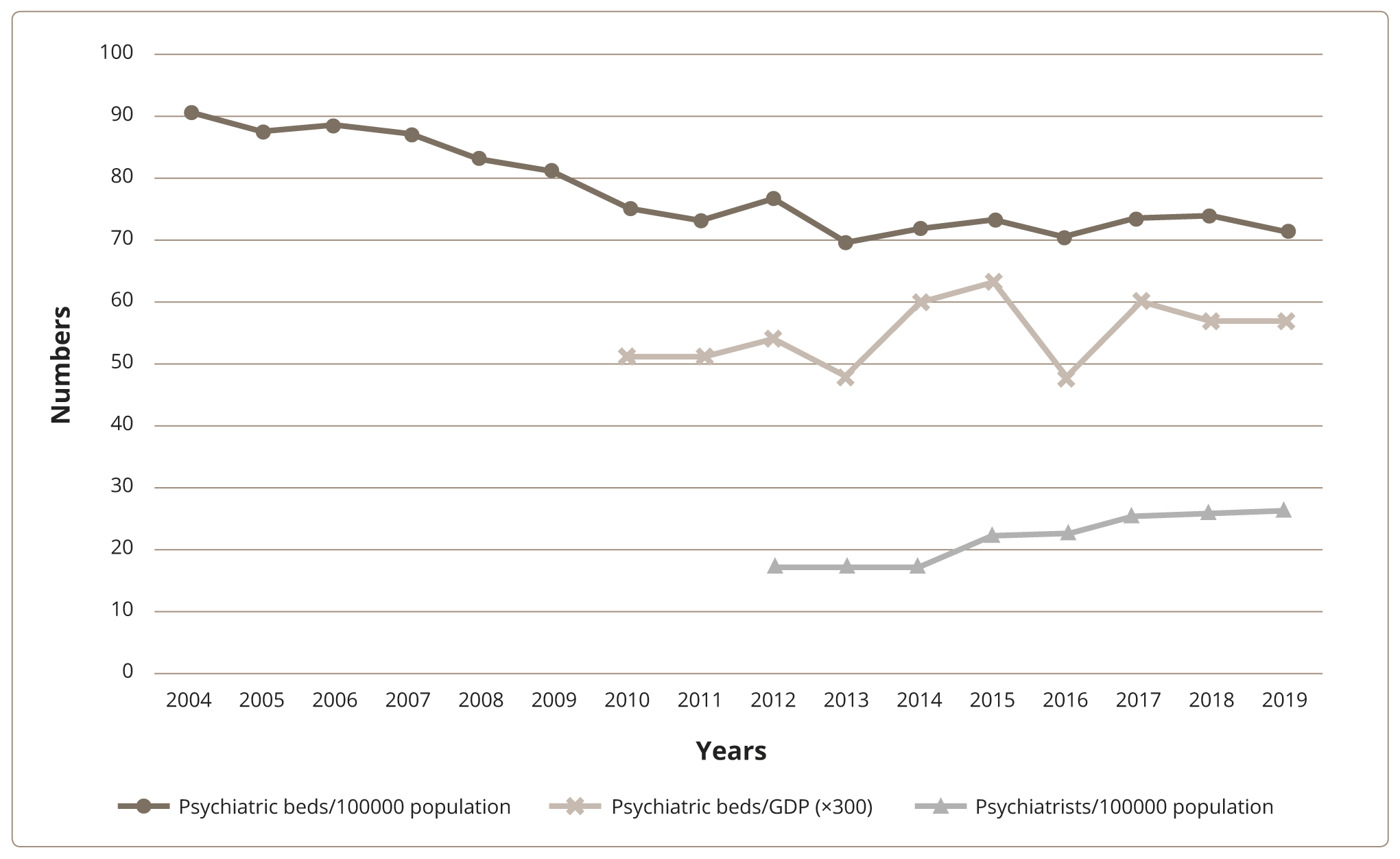

Inpatient facilities remain the first point of contact for patients in Greece, but there is a multifaceted political drive to switch the focus of care to the community. The Ministry of Health, mental health professionals and the independent authority “The Greek Ombudsman”, to name a few, have examined this issue, while studies have highlighted the service gap in the community and primary care.2,3 As a result, most large hospitals and asylums have closed, and the number of psychiatric beds is steadily falling (2019 figures: 71.45/100000 population). In their place, several types of community care services have emerged. These have been primarily state-funded, either through direct investment into the public health system, or through subsidizing private initiatives. The private sector itself has also stepped in with the development of long-term care homes to fill the gap left by the asylums. There are also many non-governmental organizations and local community operations offering a long list of individual options for psychosocial integration and therapeutic community options. The backbone of the community mental health service is composed of the following types of services:

- Community and Outpatient Services: Community mental health care in Greece is mainly offered by outpatient clinics located in general hospitals or psychiatric hospitals. However, community services per se, such as community mental health centres, mobile units and urgent intervention units, are gradually being deployed. Mobile units in particular offer a massive advantage in a mountainous and island nation like Greece, and often resort to creative means in order to reach isolated parts of the country. Other community services involve private practices and psychotherapy services. These services intertwine and cooperate well as a rule, but coordination can sometimes be a challenge.

- Day Hospitals: In the last decade there has been a significant increase in this specific type of centre. Their goal is the prevention and reduction of disability and institutionalization of patients with chronic mental disorders. Daily care centres aim to reintroduce patients with chronic mental disorders to the community as active members. It is vital for such rehabilitation services to collaborate closely with allied professionals such as occupational therapists and social workers. In addition to regular day hospitals, other types exist, such as occupational rehabilitation centres, patient clubs, apprenticeships, supervised work and skills training programs, and self-help groups. Among them, the so-called “Social cooperatives of limited responsibility”, a form of mental health cooperative business, usually funded by the government, offers assertive occupational and social rehabilitation interventions, with a focus on societal reintegration.

- Hostels and Sheltered Housing: These services have a specific target. They accommodate patients with chronic mental disorders who are unable to fend for themselves and lack a social support network. They comprise post-discharge hostels, hostels for medium-term and extended stay with various supervision forms, boarding schools, secure apartments (supervised placements usually for five to 10 residents), and foster families. Sheltered housing can be a useful interim solution for patients with chronic mental disorders who lack a family or a close safety network. However, when this “interim solution” becomes chronic, a new type of institutionalization ensues.

THE HUMAN FACTOR

According to Eurostat, Greece has 26 psychiatrists per 100000 population, only second behind Germany among EU countries, and the number is on the rise. By contrast, according to the WHO Global Health Observatory4 in 2016 only 12.75 mental health nurses were available per 100000 population, one of the lowest numbers in the EU. According to the same dataset, 8.78 psychologists were available per 100000 population, but this number is confounded by licensing issues. In Greece, the vast majority of mental health professionals work in large city centres, whilst the rest of the country has evident disproportionate shortages. Numbers aside, continuing professional development is not always actively thought of and is not centrally regulated for mental health professionals. As a result, a culture of ongoing reform is not easily maintained among the workforce. A silver lining is highlighted in the aforementioned ex post evaluation of the psychiatric reform:2 according to the report authors, Greek mental health professionals have great local and clinical leadership potential, and this potential has not yet been harnessed due to their positioning and the lack of a clear hierarchy.

PERSPECTIVES AND CHALLENGES

Greece has come a long way since Leros5 and, despite financial and societal setbacks in the last few years, has managed to push its psychiatric reform forward.

Рисунок 1. Тенденции реформы психиатрии в Греции: тенденции в психиатрических койках и общем количестве психиатров.

Figure 1 shows the falling trends in psychiatric beds and a simultaneous rise in the total number of psychiatrists indicates the growth of community mental health care, as shown by the data obtained by Eurostat. Beyond the development of new services, social, economic, and legal standards had to adapt to modern times and incorporate international experience. Importantly, the culture had to shift; mental health had to be elevated in importance and psychiatry had to gain parity of esteem. This change was recently heralded by the appointment of a dedicated Minister for Mental Health, a European first. Despite this good news, there are still organizational shortcomings, a relative lack of a culture of clinical governance, and widespread societal stigma regarding mental health.

Integrated care

Many modern mental health care systems aspire to integrated models of care, as proposed by the World Health Assembly.6 As far as Greece is concerned such an aspiration is simultaneously its triumph and its nemesis. Its nemesis, because integration requires good organizational skills — not Greece’s strong suit. Its triumph, because integrated care — if managed well — has enormous potential in Greece. This is because the country has strong, but largely unlinked institutions: physical health services, social care services, the armed forces, the Orthodox Church, Non-Governmental Organizations, various cooperatives and other social institutions, and active private initiatives.7

Patient rights

One of the main challenges still remaining is the high number of involuntary hospitalizations in Greek psychiatric clinics. For instance, involuntary admissions at the Department of Psychiatry, University Hospital of Larisa, constitute about 65% of total admissions, while this percentage rose to 78% during the COVID-19 pandemic (authors’ unpublished audit data). Reducing involuntary admissions is a milestone target in the transition towards a new community-centred Greek mental health care system, which will be better positioned to safeguard patient rights.8

Clinical governance and leadership

Another shortfall of the Greek system of mental health care is the absence of a culture of clinical governance and leadership across ranks and disciplines. Essential systemic functions like quality improvement are the exception, not the rule. Simple principles, like evidence-informed service development guided by indices of need, effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness, are seldom used even by policy makers and governmental agencies. Without this framework, a clear assessment of current provisions is not available. Provided Greek mental health professionals and policy makers develop a culture of clinical governance and leadership, modern information technology can provide them with the means to search, observe, trace and finally improve the quality of care given to patients.9

Education

To achieve a meaningful mental health service reform, one must also achieve a cultural reform with mental health professionals. This is best achieved through education, and in particular the development of attitudes such as person-centred psychiatric provision,10,11 respect for human rights and preventive psychiatry. The evolution of a framework of professional development for Greek psychiatrists is imperative and it is the responsibility of the government to empower the Hellenic Psychiatric Association (and other professional associations) to develop and deliver that framework.

Preventive psychiatry

Preventive psychiatry (i.e., mental illness prevention and mental health promotion) is a major point of leverage for the further development of the Greek mental health reform. Combined with evidence-informed service development, prevention can yield remarkably high returns on investment. Smart specific primary and secondary preventive interventions, combined with tertiary prevention through rehabilitation, are a cost-effective and clinically effective investment with guaranteed returns. From an economic and service viability perspective, preventive programs are effective in a three-to-five-year window or earlier, thus making both managerial and clinical sense. Even mental health promotion is advantageous, given that it can yield diffuse but certain results.12,13 For example, anti-stigma campaigns may not have tangible returns on investment, yet the benefits are certain, albeit dispersed.14 Preventive psychiatry is an attitude that applies to all mental health services but is implemented chiefly in the community.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the Greek mental health care system has come a long way in recent years, but must evolve even further, despite the country’s socioeconomic difficulties, in order to improve the level of care provided to patients. Moving in tandem with the international community, Greece must support better community treatment options for mental health patients, but more importantly, Greek mental health needs to invest in education and preventive psychiatry, and to evolve its culture of clinical governance and organization. Greek society must also take an active role, through educational and informative actions, in the continuous battle against stigma.