Introduction

Peripersonal space is the space around each individual in which it controls limb movements (Graziano, Cooke, 2006). Practicing the precision of coordinating perception and action in this space supports everyday activities such as pointing in the direction of an object, reaching for it, retrieving static or moving objects as well as manipulating an object. One of the domains of training refers to the accuracy of estimating the distance of the object in relation to which an observer plans to carry out an activity. Previous studies have shown that the accuracy of object distance estimation is affected by the integration of visual, proprioceptive, and vestibular information (Tošković, 2008; 2009; 2010). When estimating the distance of an object in a distant space, visual information is integrated with proprioceptive information coming from the eye muscles and the neck muscles. However, when the object of assessment is located in a space that is in the domain of limb movement, and bearing in mind that in this space the coordination of hand movements is carried out from early childhood, proprioceptive information from arm muscles can be added to the accuracy of distance assessment.

By researching the neural basis of visual information processing, it is discovered that on the wider surface of zone 7a, there are visual-fixation neurons which are activated during the fixation of static objects. Among these neurons, there are subgroups that register distance, position, and gaze direction (Sakata et al., 1997). The activity of most neurons that register stimulus distance (depth-selective neurons) increases as the distance between the observer's eyes and the object decreases. A small portion of this subgroup of neurons shows its activity when the distances between the object and the observer increase in the range of 2 to 3 meters (Sakata et al., 1997). The results indicate that there are separate centers for processing information from the peripersonal (near) and extrapersonal (remote) space.

When performing motor activity directed by an object (e.g. capturing a static object), it is important to accurately estimate the distance at which it is located. Findings of numerous studies indicate that estimating the egocentric distance of an object in peripersonal space is most accurate when the subject relies on convergence, out of all depth cues available (Howard, 2012). However, in these situations, shorter distances (10 cm, 20 cm, 30 cm) are overestimated, while middle-range (40cm) and longer distances (60 cm) are slightly underestimated (Foley, Held, 1972; Mon-Williams, Tresilian, 1999). However, estimation errors are less than 1cm, when the object is at a distance of 25 cm to 40 cm (Howard, 2012).

In addition to visual information, proprioceptive information from the arm muscles also influence the assessment of the distance of the object to be retrieved. Previous research has indicated that depending on the accuracy of the available information and the type of task, the statement of the respondents about the position of their own hand changes. One group of studies was conducted with the intention of examining the dominance of visual or proprioceptive information when assessing the position of one's own hand, which is static. By distorting only visual or only proprioceptive information about the real position of the hand, respondents had the subjective experience that the hand is localized in a position which is between those suggested by visual and proprioceptive information, but still closer to the visually suggested location (Bagesteiro, Sarlegna, Sainburg, 2006; Lackner, DiZio, 2005). In contrast, with the distortion of visual or proprioceptive information when examining grasping movements, the observed hand location is closer to that suggested by proprioceptive information (Rossetti, Desmurget, Prablanc, 1995). It can be said that the respondents relied predominantly on visual information when they were supposed to assess the static position of the hand. On the other hand, when assessing the position of a moving hand, proprioceptive information was more important than visual information. Thus, the importance of proprioceptive information is reflected in the current correction of hand movements that the subject does not see, as well as when the subject quickly, in one movement, moves his hand to the target location (Bagesteiro, Sarlegna, Sainburg, 2006).

What should certainly not be left out is the importance of vestibular information when estimating the distance of an object. It has been observed that short-term exposure of subjects to the action of microgravity in parabolic flight (Lathan, Lockerd, 2008) or long-term exposure in space stations (Clément, Skinner, Lathan, 2013) make objects look closer than they real are. The assumption is that due to the influence of vestibular information there was a change in visual cortical responses (Brandt et al., 1998; Seemungal et al., 2013). This would mean that the accuracy of the distance estimate is affected by a change in the gravitational force.

Role of gravitational force in distance perception can be mediated by effort needed to perform certain actions. Many findings show that the estimate of the effort to cross a given distance uphill increases, if the road is steeper, and accordingly, it increases the perceived path length (Berkeley, 1709; Proffitt et al., 2003). This relation of perceived effort and distance can be seen in findings showing that distances above the observer are perceived as longer that physically equal distances in front of them (Tošković, 2004; 2009; 2011; 2013). Namely, the imaginary movement of reaching towards an object stationed above the head would be performed contrary to the gravitational force, because of which effort will be perceived as larger and object’s distance too. This can be related to vestibular information, since they register the change in the head and body position in regard to direction of the gravitational force. Changing the position of the head leads to a change in the orientation of the eyes. Reliable assessment of the egocentric distance of an object when viewed through the legs (Higashiyama, Adachi, 2006; Tošković, 2010) as well as when it is peripherally localized depends on the information about eye orientation (Blohm et al., 2008). Knowing the importance of vestibular information for perceived distance of an object, researchers tried to examine the influence of artificial stimulation of the vestibular apparatus on the accuracy of distance estimation. Stimulation with galvanic current, strength 1mA with 3s duration, applied on both mastoid bones as well as the neck of the subjects’ show an increase in the deviation of the distance estimate (Török et al., 2017). Specifically, respondents observe that the object is even more distant when it is located above the horizon while their head is raised, or that it is even closer when it is located below the horizon while their head is lowered. These results are in line with the previously mentioned results.

Having in mind above mentioned results on the importance of various types of information from different sensory modalities (visual, proprioceptive and vestibular) for the assessment of distance, the aim of our paper is to examine their individual and combined contribution to the accuracy of estimating the egocentric distance of an object in peripersonal space. So, we wanted to examine how each of the mentioned information types affects the assessment of distance in the peripersonal space, but also how it interacts with the other two types of information. Also, it was important for us to separate the possible individual effects of information from different sensory modalities on the assessment of distance from the effects that are a consequence of their mutual interactions. For example, it is important to know whether information from different sensory modalities are important for distance estimation themselves, or whether they are important only in their mutual interactions.

Materials and methods

Participants

Since in our previous studies of perceived distance anisotropy, obtained effects ranged between η2 = 0.5 and η2 = 0.75, with study power of 0.8 and alpha level of 0.05 we would need a minimum of 10 participants in order to obtain similar effects in this study. Accordingly, this research involved 22 psychology students from the Faculty of Philosophy in Kosovska Mitrovica, both genders (12 females), aged 18 to 31, M = 20.95, Sd = 3.24. All subjects were right-handed and had normal or corrected to normal vision. Informed consent was collected from all subjects prior to their participation in the experiment.

Stimulus and apparatus

According to specific needs of this research, a movable stand with a flat surface (platform) was designed. The stand is made so that there is a possibility of adjusting the height at which the platform is located, in order to adapt to individual differences in the height of subjects, i.e. the platform is always adjusted to the height of the eyes of each subject. The surface of the platform is white with a black line along the entire length, with surface area of 10 cm * 90 cm and it was used to expose the stimulus to the subject. A yellow rectangular parallelepiped, with dimensions 2.5 cm * 4.5 cm * 1.5 cm, horizontally oriented, attached to the platform with a magnet was used as a stimulus (Fig. 1).

Procedure

General task of the subjects was to estimate the stimulus distance, which was varied and used as one of experimental factors. The stimulus distance refers to the egocentric distance at which the stimulus is shown to the subject (for 2 seconds, after which it is removed) and it had three possible values, 20 cm, 40 cm and 60 cm, only known to experimenter, with subjects not knowing their values.

In order to examine the contribution of information from each sensory modality to the accuracy of estimating the egocentric distance of the stimulus, we used three versions of the tasks. In all versions, visual information was always available while the availability of proprioceptive and vestibular information was varied. The task type is related to the way in which the examinee is expected to reproduce the distance at which the stimulus was located. There were three different distance estimation tasks: (1) The motor reproduction task, in which the examinee is expected to move the stimulus with his hand to the position where he originally saw it. The task is designed to examine the contribution of visual and proprioceptive information from the arm muscles to the accuracy of distance estimation; (2) Guidance task, in which respondents are expected to use words closer/further to guide the researcher to move the object to the place where they think the stimulus was located. In this task, only visual information is available to the respondent during distance estimation; (3) The verbal assessment task, in which subjects are expected to estimate the distance of the stimulus in centimeters, and to say at what distance the stimulus is located, using metric units previously mentioned. In this task, in addition to visual information, the respondent uses higher cognitive processes, i.e. reasoning about estimated distance. Depending on the type of task, subjects were told: "Carefully examine the distance of the object relative to yourself and after I remove the stimulus, you need to reproduce the distance of the stimulus as quickly as possible by: 1. using your hand; 2. guiding me to do so; 3. verbally estimating the distance in centimeters." The respondents were allowed to rest for 5s after rotation and then encouraged to give an answer as accurately as they could (Cheung, Hofer, 2003; Wang, Spelke, 2000). We decided not to provide performance feedback or information about the maximum distance of the presented stimulus because respondent would adjust their response based on received information, which may compromise our aim in investigating contribution of individual sensory information during estimation process (Wearden, Jones, 2007). All subjects were naive and did not receive any additional training prior to the experiment since we were interested in comparing their non-trained estimates.

Besides stimulus distance and task type, we also included two experimental situations, referring to whether the subject was rotated or not around vertical axis before giving an estimate of the distance at which the stimulus was located. Having in mind the procedures in previous studies (Hermer, Spelke, 1996; Lourenco, Huttenlocher, 2006; Waller, Hodgson, 2006; Wang, Spelke, 2000) and findings related to the symptoms of driving sickness, we decided that rotation speed will last for 1 minute. In half of the experimental situations, we passively rotated subjects, at a constant speed of 15 times per minute. During the rotation, the respondent’s eyes were closed. Subjects opened their eyes immediately before estimating the distance on the platform. In this way, we avoided stabilization of the retinal image by involuntary eye movements (nystagmus) activated by VOR during the passive rotation process (Khan, Chang, 2013).

Generally, all subjects participated in all 18 situations, i.e. all combinations of experimental factors (3*3*2). The order of situations was randomized for each subject: 3 stimulus distances, 3 task types and rotation (with or without). Prior to performing an estimate, subjects were acquainted with the ways in which they should reproduce the location of the stimulus, as well as with the fact that in half of the experimental situations we will rotate them around vertical axis. In order to prevent the prolonged influence of the rotation consequences on subsequent estimates, a break of 15 minutes (Chang et al., 2023) was made between each distance estimation task. During the experiment the respondents wore glasses with 1mm wide horizontal apertures which limit the eye movements and allow only convergence. Before the experiment started, the height of the stand was adjusted to each subject so that they could rest the tip of their nose on the platform with the stimulus. The platform was not attached to the subjects' glasses, so subjects could quickly and easily move away from the platform during the break. During the assessment, the respondents sat upright in the chair. Before the main part of the experiment all subjects performed a few trial distance estimations. This would allow the subjects to get used to the experimental situation and feel comfortable during the duration of the experiment (about 3 hours per respondent).

Results

The deviation from the given standard distance was calculated for each individual distance estimate. In case the respondent underestimated the stimulus distance in relation to the standard, the value of the deviation was negative and vice versa. So, the dependent variable was an error in estimate distance. According to Hair et al. (Hair et al., 2010) and Bryne (Byrne, 2013) skewness values between -2 to +2 and kurtosis values between -7 to +7 indicate normally distributed scores, and all values on dependent variable fulfilled that condition. Based on the performed three-factor analysis of variance for repeated measurements, it was determined that there is a main effect of the task type and distance at which the stimulus is located, as well as the interaction of task type and stimulus distance and interaction of task type and rotation of respondents (Table). No statistically significant differences between groups of participants were detected, such as gender differences. Accordingly, we will present only effects of experimental factors related to the aims of our study.

Table

Significance of the effects of task type, stimulus distance and subject rotation on the distance estimate

|

|

df1 |

df2 |

F |

p |

η² |

|

Task type |

2 |

42 |

47.438 |

.000 |

.693 |

|

Stimuli distance |

2 |

42 |

12.989 |

.000 |

.382 |

|

Participant rotation |

1 |

21 |

.002 |

.963 |

.000 |

|

Task type * Stimuli distance |

4 |

84 |

3.077 |

.020 |

.128 |

|

Task type * Participant rotation |

2 |

42 |

5.070 |

.011 |

.194 |

|

Stimuli distance * Participant rotation |

2 |

42 |

.339 |

.714 |

.016 |

|

Task type* Stimuli distance * Participant rotation |

4 |

84 |

2.356 |

.060 |

.101 |

It can be said that the accuracy of stimulus distance estimation will depend on all three mentioned factors: task type, distance at which the stimulus is located and on whether the subject is rotated around its axis or not. Stimulus distance effects are expected and they only show observers sensitivity on different distances – further distances are estimated as larger. But, task type effects and their interactions with stimuli distance and participants’ rotation are indicative for our research aims. Since the task type showed significant interactions with both stimulus distance and subject rotation, we performed Scheffe post-hoc tests, in order to examine the differences between the three tasks, separately in situations where subjects were rotated or not, and on three different standard distances (Appendix).

Between the situations with and without the rotation of respondents (disorientation), there were no significant differences in the errors of estimated distance, in any of the tasks, nor in any of examined standard distances. The results indicate the marginal significance (p = 0.054), only when participants were estimating the stimulus at a distance of 40 cm in the motor reproduction task. The direction of the differences is such that the respondents make smaller errors in distance estimation when they were not rotated around vertical axis than when they were rotated. But rotation does show significant interactions with task type, and therefore we will show differences between tasks separately for a situation with and without rotation.

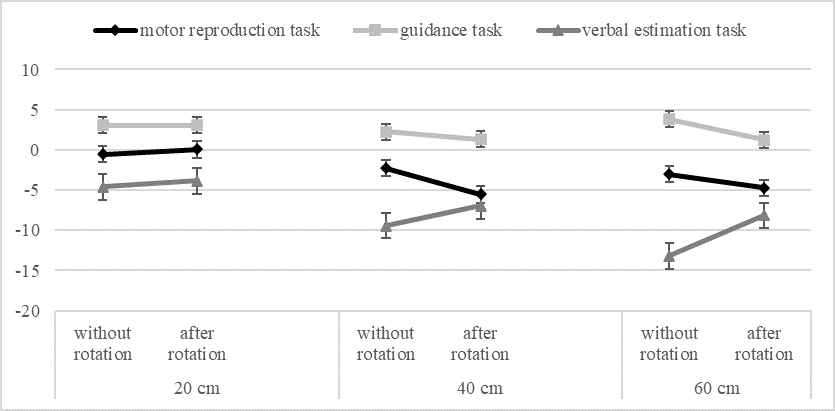

When the respondents were not rotated, all three tasks differed from each other, at all three standard distances. The differences are such that in the guidance task the respondents overestimate the given distances, in the motor reproduction task the errors are close to the zero or there is a slight underestimation of the distance, while in the verbal assessment task the respondents underestimate the given distances. In more detail, at the closest distance, of 20 cm, the errors in the guidance and verbal assessment task are similar in intensity, but they are in the opposite direction, i.e. overestimation occurs during guidance and underestimation during verbal assessment. At other distances, 40 cm and 60 cm, the errors in verbal assessment tasks are also in the direction of underestimation, but they are far more intense than the errors obtained in the other two tasks. As for motor reproduction task, at the closest distance, of 20 cm, is estimated quite precisely, almost without error, while greater distances, 40 cm and 60 cm, are slightly underestimated. The underestimation of the distance in the motor reproduction task at 40 cm and 60 cm is of similar intensity as the distance overestimation in the guidance task, i.e. the errors are of similar intensity, only in the opposite directions (Fig. 2).

In situations where distance estimates were given after the subjects were rotated (disorientated), the differences between the three different tasks still exist, but are somewhat smaller. Namely, in this case as well, in the guidance task the given distances were overestimated, while in the verbal assessment task, they were underestimated, for all three standard distances. In the motor reproduction task, as well as in situations without subjects’ rotation, the closest distance, of 20 cm, is estimated quite accurately, while greater distances, 40 cm and 60 cm, were underestimated. This underestimation in the motor reproduction task, at a distance of 40 cm, is similar to the underestimation in the verbal reproduction task (they do not differ significantly). At a distance of 60 cm, the errors in the motor reproduction are larger than in the guidance task, and smaller than in the verbal assessment task. Thus, after rotating the subjects, the profile of intensity and direction of errors (underestimation or overestimation) is similar to that in situations where the subjects were not rotated, but the differences between the three tasks were somewhat smaller (Fig. 2).

Interaction of task type and stimuli distance, shows that in the guidance task, the errors in estimating the distance are the same at all stimulus distances regardless of whether the subjects are rotated or not. In the verbal assessment task, the errors are the same at all three distances in situations where the assessments were given after the rotation of the respondents. If, on the other hand, the estimates were given without rotation of the subjects, the errors were significantly smaller at the closest distance of 20 cm in relation to the remaining two distances, 40 cm and 60 cm. In the third, motor reproduction task, the differences in errors of estimated distances are somewhat more pronounced, i.e. the errors at the closest distance are smaller the errors of the other two. In motor reproduction task, with and without rotating the subjects, at a distance of 20 cm there are almost no errors, i.e. the distance is estimated quite accurately, while at greater distances the errors increase and the distance is underestimated (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Previous studies have highlighted the impact of visual information as dominant for planning and implementing motor actions (Bagesteiro, Sarlegna, Sainburg, 2006; Harris, Mander, 2014) However, in the peripersonal space, in addition to predominantly visual information, observers also rely on proprioceptive, especially for the purpose of correcting hand movements when visual feedback is not available (Bagesteiro, Sarlegna, Sainburg, 2006; Rossetti, Desmurget, Prablanc, 1995). The third very important source of information about the distance of the object is the vestibular apparatus. The importance of vestibular information is not only reflected in the perception of the action, gravity and acceleration. This is indicated by the research in which the respondents estimated the distance traveled only on the basis of information about the acceleration of the body (von der Heyde et al., 2000). The importance of vestibular information is also indicated by errors in reaching for a peripherally localized object, related to the perception of head position (Blohm et al., 2008) as well as estimating the distance of the object when viewed through the legs (Higashiyama, Adachi, 2006; Tošković, 2010). Also, it should be noted that at the neural level, all information is integrated with each other at some level of processing. Some studies state that due to artificial stimulation of the vestibular apparatus, there was a change in the visual cortical responses (Brandt et al., 1998; Seemungal et al., 2013).

Our intention was to examine the contribution of visual, proprioceptive, and vestibular information to the accuracy of estimating the egocentric distance of a stimulus in the peripersonal space. The task of the respondents was to see the stimulus at one of the three distances (20 cm, 40 cm and 60 cm), to reproduce the distance themselves (motor reproduction task in which both visual and proprioceptive information are available), lead the researcher to do it (guidance task in whom visual information is available) or to estimate the distance in centimeters (verbal assessment task in which visual information is available but also higher cognitive processes are engaged). Considering that the respondents acquired formal education in mathematics, verbal distance estimation was based on previously acquired knowledge but also on experience in estimating distance in metric units in a space within arm's reach. Although there are many possible sources of error during distance estimates in our experiment, we were primarily interested in differences between estimates given on two directions. Whatever those additional errors might be, they should be constant on both examined viewing directions (horizontal and vertical) and accordingly should not affect primary results, since they are not correlated with our main independent variable, viewing direction. For example, during verbal estimation task, it is possible that the magnitude of the subjects' error was associated with the criterion that the subject defined for himself or herself when solving this task, but this criterion is probably constant on both viewing directions and it should not change the main effect, difference in distance estimates on two directions. On the other hand, decrease in error in verbal response after rotation may indicate that the subjects in difficult conditions pay more attention to the task and, as a result, give more accurate answers. This can be further investigated maybe through activation of Type I and Type II processes (Kahneman, 2011; Kannengiesser, Gero, 2019). Prior to the assessment, respondents were either rotated or not. By rotating the subjects around their vertical axis, the effect of disorientation was achieved, which affected vestibular information when estimating the distance. Each subject participated in all experimental situations. In this way, we enabled a comparison of the achieved results depending on the type of sensory information available.

The task of verbal assessment proved to be the least reliable way of estimating distance. In this task, the respondents made the most errors in the direction of underestimating the given distance. Thus, the combination of visual information and higher cognitive processes such as reasoning, relying on knowledge of metric units, gives the worst result in estimating distance. This result is consistent with previous studies in which using measurement units for estimates (mm or cm) lead to underestimation of the displayed line length or underestimation of the image exposure time (Ogden, Simmons, Wearden, 2021). The errors in the estimated distances remained the same after the rotation of subjects, which means that the change in vestibular information did not significantly affect the distance estimates in this type of a task. What is interesting about this task is that as the distance of the standard increased, the error in estimating the distance made by the respondents increased linearly.

The guidance task, i.e. estimating the distance by instructing the experimenter to move the stimulus (closer or further) until the desired estimated distance is reached, proved to be somewhat more reliable. In this type of a task, respondents rely solely on visual information and show systematic overestimations of given distances. This finding is consistent with earlier ones that indicate the dominance of visual information in action planning (Bagesteiro, Sarlegna, Sainburg, 2006).Namely, the procedure used in investigation of the movement planning phase, in which the estimation of the distance of the object is based only on the visual information without hand movements, coincides with the guidance task used in our study. Stimulation of the vestibular system, i.e. disorientation of the subjects by rotation, did not lead to a change in errors in the assessment of distance in this type of task either. So, if only visual information is available, the distance is estimated more precisely than if we rely on some higher cognitive processes (reasoning, knowledge of metric units), i.e. these higher cognitive processes seem to interfere with the assessment of distance. On the other hand, the hyperactivation of vestibular system does not significantly change the process distance estimation, because the errors in estimated distance remained the same after the rotation of the subjects.

In the motor reproduction task, the subjects gave the most accurate estimates of the stimulus distance, but only at the closest distance, of 20 cm. In this situation, the subjects reproduced the distance fairly accurately and the errors were close to zero. At longer distances, 40 cm and 60 cm, errors occur in this task as well, in the direction of underestimating the given distances. In this task, for when estimating distance respondents rely on visual and proprioceptive information from the arm muscles and we can say that this combination of information gives the most accurate distance estimates, but only at the shortest distances. Accordingly, it seems that proprioceptive information has the role of correcting the movement of the hand directed towards the goal, during its performance, as previously established (Bagesteiro, Sarlegna, Sainburg, 2006; Rossetti, Desmurget, Prablanc, 1995). The trend of errors generally does not change with the rotation of respondents, even in this task. In fact, there is one marginally significant difference, but only at a distance of 40cm, such that respondents seem to make fewer mistakes in estimating distance when they were not rotated before the assessment than when they were rotated. In addition, the rotation of the respondents leads to increasing the errors in this task for greater distances, and they become more pronounced than in the guidance task (visual information only).

Summarizing the results obtained on three different distance estimation tasks, we see that the inclusion of higher cognitive processes in distance estimation leads to the largest errors and we can say that it does more harm than good to such estimates in peripersonal space. In contrast, the combination of visual and proprioceptive information gives a more accurate perception of distance at the closest distances, while at greater distances this combination of information gives almost as accurate estimates of distance as relying only on visual information. It should also be mentioned that in the guidance task, the respondents always overestimated the distance, while in the motor reproduction and verbal assessment tasks, they almost always underestimated the distance. That is, at greater distances in the peripersonal space, visual information shows a tendency to overestimate distance, and a combination of visual and proprioceptive leads to underestimation of a given distance. Finally, the disorientation of subjects by rotation leads to increasement of errors in distance estimate based on combination of visual and proprioceptive information, i.e. at larger distances of 40cm and 60cm estimates were less accurate than based on purely visual information. In a situation where subjects give distance estimates after rotation, distance estimation errors are greater in the motor reproduction task (combination of visual and proprioceptive information) than in the guidance task (only visual information is available). This last finding indicates the importance of vestibular information and their interaction with the visual and proprioceptive in distance assessment.

As far as vestibular information is concerned, we see that in almost all task types there was a difference in distance estimation errors between situations when subjects were rotated and when they were not. Also, a direct comparison of errors in the two situations did not give a significant result, i.e. main effects of rotation were not significant. Nevertheless, the rotation of the respondents did show a significant interaction with the task type, which is reflected in the compression of the differences between the three tasks when assessments are given after the rotation of respondents. Thus, stimulating the vestibular system by rotating subjects did not give effects on distance estimation errors in each individual task, but it did reduce the differences in errors between the three tasks. It looks like as if the disorientation of the respondents in some way reduced the differences that occurred as a consequence of combining different sensory information in three different tasks. In addition, the disorientation of subjects at greater distances, 40 cm and 60 cm, led to the combination of visual and proprioceptive information (motor reproduction task) giving a less accurate estimate of distance than purely visual information (guidance task). These findings are in line with previous research examining the impact of vestibular information on the accuracy of distance estimation, in which it was found that a change in the position of the body of the subject affects the accuracy of the estimation (Tošković, 2004). However, in these studies, vestibular information was always present and intact. The change of participant’s position solely does not change the constant effect of gravitational force on the body. In present study, however, disorientation caused by rotation, did affect vestibular information and in some sense modified it during the distance estimate.

Conclusions

Based on the results of the research, we can say that the respondents rely on the integration of all the information available to them from the senses in order to most accurately estimate the egocentric distance. An interesting trend is that relying only on visual information leads to overestimation of distance, while the interaction of visual and proprioceptive information, as well as the combination of visual information with higher cognitive processes leads to distance underestimation.

At closer distances, the combination of visual and proprioceptive information gives more accurate distance estimates. The estimates obtained in this way do not change with the variation of the quality of vestibular information. The importance of the interaction of the two modalities in the assessment of distance, visual and proprioceptive, most likely stems from the role that proprioceptive information plays in correcting the movement of the hand directed towards the goal. However, at greater distances in the peripersonal space, the interaction of visual and proprioceptive information gives equally accurate estimates as relying only on visual information, but in the opposite direction — the interaction of two types of information leads to underestimation of distance, and usage of only visual information leads to distance overestimation. The change in the quality of vestibular information further changes this relationship, because the disorientation of the respondents leads to the fact that the combination of visual and proprioceptive information becomes less precise when estimating the distance from relying on purely visual information. These data suggest that the cognitive system in a state of disorientation begins to rely solely on visual information, while other modalities role is being modified.

On the other hand, the inclusion of higher cognitive processes in distance assessment has been shown to be a disruptive factor. Our results are consistent with previous studies on distance conservation. Namely, researchers have explained similar findings by assuming an increased cognitive load during distance estimation by using metric units, which is associated with increased engagement of short-term memory resources and executive functions (Ogden, Simmons, Wearden, 2021; Ogden et al., 2018). The task of verbal assessment, which, in addition to visual information, also includes knowledge of metric units and, to some extent, reasoning, leads to the least accurate distance assessments. Thus, it seems like the cognitive system integrates information from different sensory systems when estimating distance, but the inclusion of higher cognitive processes complicates such assessments and leads to larger errors.

Limitations. The limitations of the study are integrated into our plans for further research in which we would explore the influence of primarily vestibular information on the accuracy of distance estimation in different directions of the subject's body orientation. Also, by using advanced technologies, such as the galvanic vestibular stimulator, which directly affect the work of the vestibular apparatus, we will be able to obtain more precise data on the contribution of vestibular information to the accuracy of distance estimation.