In English

Introduction

Multiple studies have demonstrated a correlation between the quality of individual psychotherapy or counseling sessions and the overall effectiveness of the process

[Saxena, 2023; Lingiardi, 2011; Wrede, 2023]. Examining session quality also enhances our understanding of the relationship between the psychotherapeutic or counseling process and long-term outcomes

[Lingiardi, 2011].

Although session quality and outcome are often used interchangeably in the literature [1; 6, 33; 37; 38], it is important to note that they have different meanings. Session quality refers to the processes that occur during a session, such as empowerment or clarification of meaning, and the subjective attitudes towards them

[Hill, 2002; Nasim, 2021]. Session outcome, on the other hand, refers to the final results, such as symptom reduction and improved well-being

[Igra, 2022; Erekson, 2022]. The relationship between session quality and outcome can be complex due to external variables beyond the psychotherapeutic or counseling interaction, often referred to as inter-session experiences or mental representations (e.g., recreating the therapeutic dialog)

[Gablonski T.-C, 2023; James, 2022]. This means that a session can be considered high-quality even without observable improvement. Nevertheless, research suggests that the quality of a session is associated with its subsequent outcome

[Mander, 2015; Lai, 2022].

But what defines a high-quality session? How is it determined if a session has high quality? Presently, the scientific community lacks consensus regarding the selection of tools for evaluating individual session quality or even establishing a clear definition of session quality. Although there are various instruments available, comprehensive analytical reviews clearly delineating their distinct applications, merits, and perspectives on high-quality sessions are notably absent in contemporary literature.

Therefore, this literature review aims to identify the most relevant, valid, and widely used instruments for evaluating session quality and derive the main characteristics of high-quality sessions on this basis. The analysis examines the strengths and weaknesses of each assessment instrument and explores the perspectives on session quality characteristics embedded within each of them. The literature review focuses on pantheoretical (universal) methods that are used to evaluate psychotherapy or counseling session quality with adult clients, regardless of the therapist's approach or theoretical orientation.

Literature search procedure

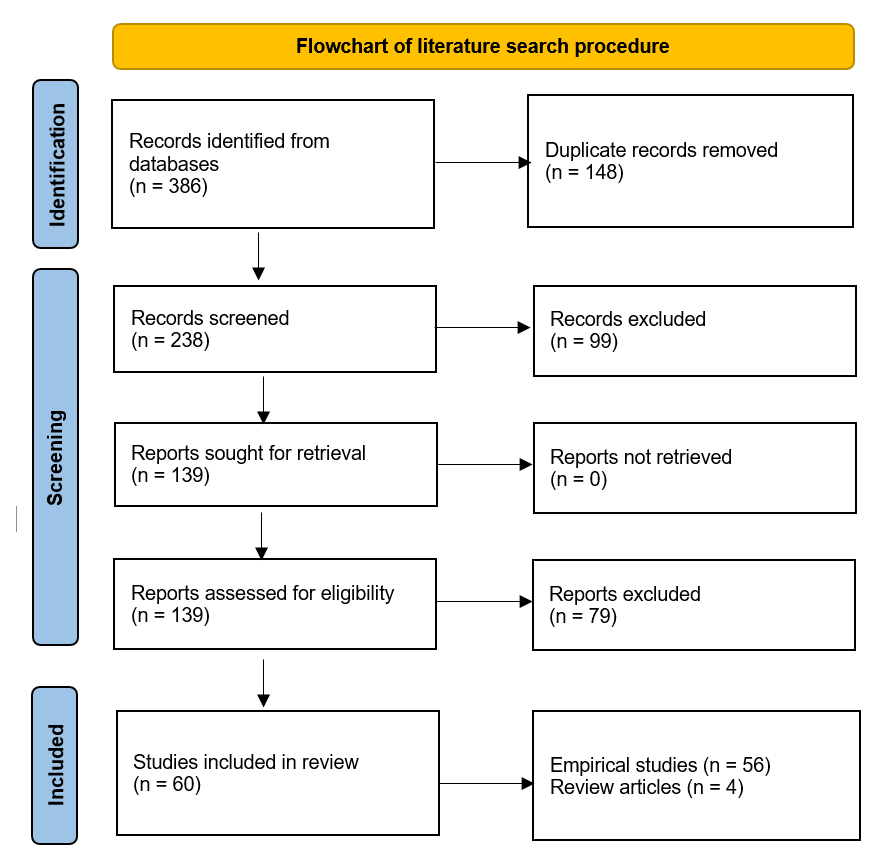

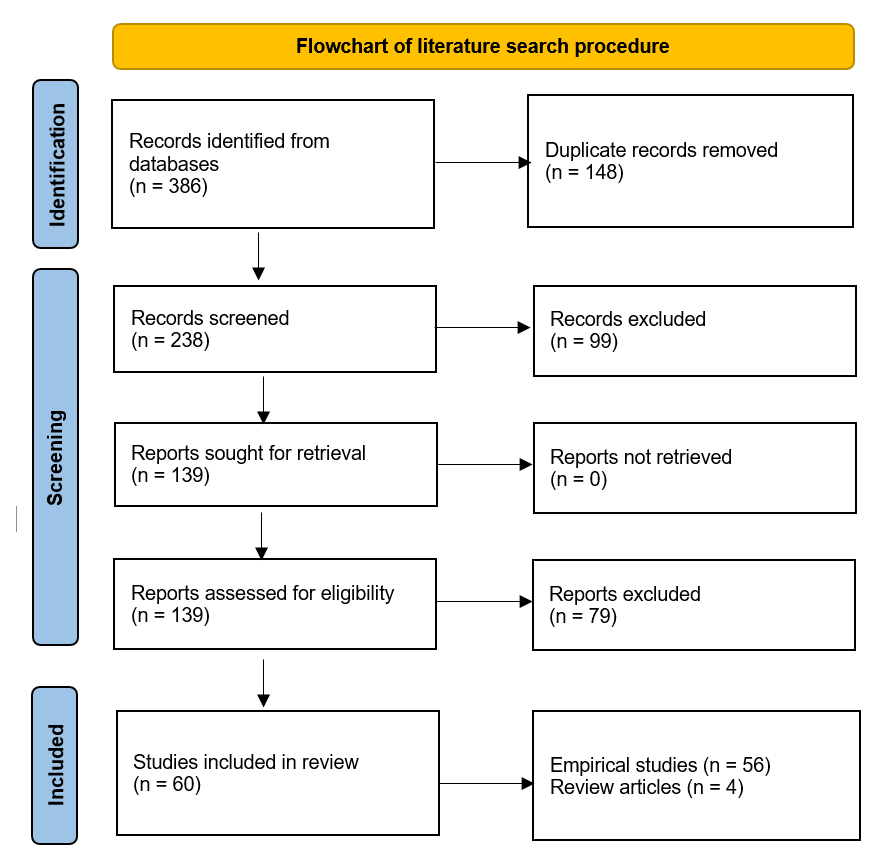

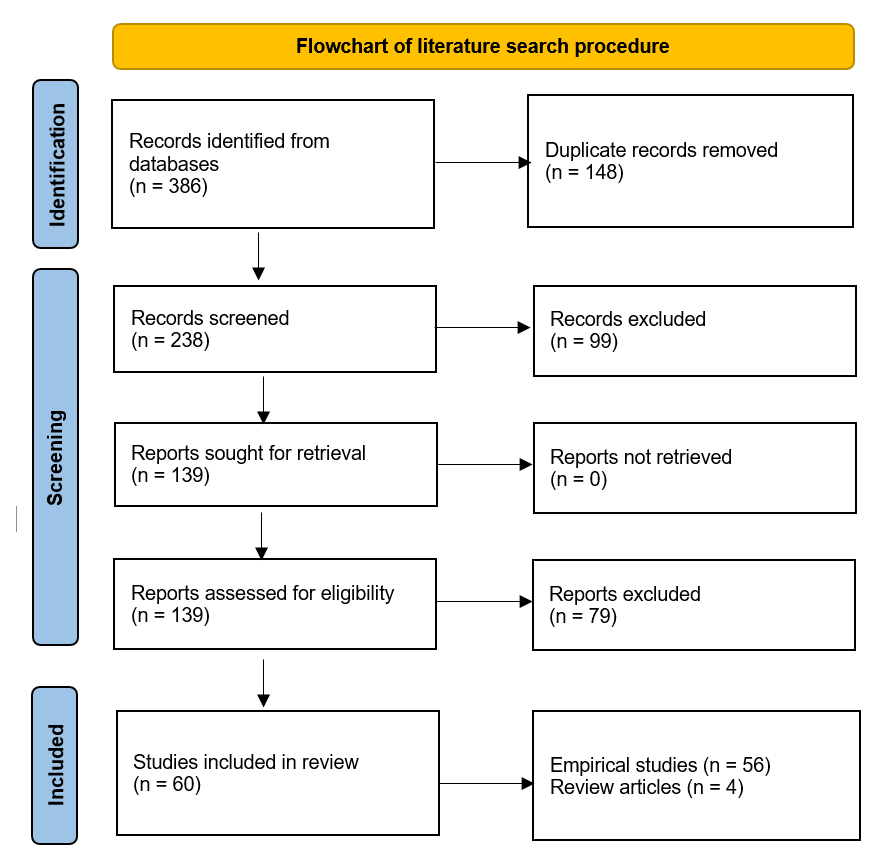

To achieve the aforementioned aim, the scientific literature of the last ten years was reviewed. The publications were searched in APA PsycInfo, Scopus, Web of Science databases by abstracts, titles and keywords using the following search query: («session quality» OR «perceived quality» OR «session satisfaction» OR «session evaluation» OR «session impact» OR «postsession outcome» OR «micro-outcome» OR «session outcome» OR «perceived outcome» OR «session effectiveness» OR «session efficiency» OR «session efficacy» OR «session efficacy» OR «perceived helpfulness» OR «session helpfulness») AND («psychotherapy» OR «psychological counsel*»). Initially, 386 scientific publications were obtained. After removing duplicates, 238 publications remained. Next, abstracts screening was performed, leaving 139 publications. Finally, after analyzing full-text documents, 65 relevant publications were identified. However, during the writing of this paper, 5 of the identified articles were retracted by the authors due to ethical issues. As a result, there were a total of 60 publications examining the quality of psychotherapy or psychological counseling sessions, consisting of 56 empirical and 4 review articles (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Flowchart of literature search procedure in APA PsycInfo, Scopus, Web of Science databases

Furthermore, articles published in the last 10 years in the Russian electronic scientific library eLibrary were searched by abstracts, keywords, and titles with the same search query, but in Russian. Among 120 publications identified, only 2 met the criteria upon abstract analysis, with access to the full text granted for 1 publication.

The inclusion criteria encompassed empirical or review articles in any language that investigated session quality as a stand-alone parameter or in relation to other aspects within a single session or the whole psychotherapy or counseling process. Due to the confusion in terminology, we also included the keywords for session outcome. However, for the article to be included in our review, it must have focused on session processes rather than changes in well-being following the session. The exclusion criteria comprised studies conducted outside the context of psychotherapy or psychological counseling, lacking evaluation of session quality, or involving participants under 18 years old.

Results

The methods for evaluating session quality described below are represented in approximately 97% of the contemporary literature that was found and analyzed. The remaining 3% of the publications conducted session quality evaluation with a single question or statement, such as “Please rate the overall quality of today's session” (e.g.

[Klug, 2022]).

Session Evaluation Questionnaire

The Session Evaluation Questionnaire (SEQ), developed by William B. Stiles in 1980, is the predominant method for assessing session quality, appearing in half of the reviewed publications (N = 29). Available in 18 languages, the SEQ-5, its fifth version, is widely utilized, featuring 21 items with evaluative bipolarization on a 7-point Likert scale. The SEQ exhibits high internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha: Depth = 0,87, Smoothness = 0,93, Positivity = 0,89, Arousal = 0,78)

[Stiles, 2002].

The SEQ measures session quality from both psychologist and client perspectives, with scales for Depth, Smoothness, Positivity, and Arousal. The first two scales reflect attitudes toward the past session, representing session quality, while the latter two focus on mood after the session, indicating session outcome. Independent observers use a modified SEQ version, which includes the same Depth and Smoothness scales as for clients and therapists. However, in the second part, they evaluate the probable client's and counselor's feelings after the session separately.

Recent research has utilized SEQ mostly to investigate the impact of pre-session meditative practices on session quality

[Ivanovic, 2016], the correlation between session quality and interpersonal synchrony

[Zimmermann, 2021], therapeutic alliance

[McCarrick, 2018], transference and countertransference

[Rocco, 2021], therapist's modality and theoretical orientation

[Chen, 2021], self-disclosure

[Jowers, 2019], personal characteristics

[Reading, 2019], silence

[Zimmermann, 2021a], moments of insight during the session

[Nasim, 2021], and responsibility attribution

[Lai, 2022]. The Depth scale is often used for this purpose.

SEQ defines a low-quality session by weakness, worthlessness, emptiness, tension, and distress, while a high-quality session is characterized by power, value, fullness, relaxation, and comfort.

Reliable and concise, SEQ is suitable for scientific research and psychotherapeutic practice, providing insights into session depth, smoothness, and participants' emotional state immediately after the session.

Session Evaluation Scale

The Session Evaluation Scale (SES), developed by Clara E. Hill and Ian S. Kellems in 2002

[Hill, 2002], is the second most utilized method for assessing session quality, appearing in about 17% of reviewed articles (N = 10). Originally, the SES consisted of four client-rated statements on a 5-point scale. In 2006, Robert W. Lent added a fifth item to assess the overall session effectiveness and developed a parallel version for psychologists

[Lent, 2006].

The responses to the five items are summed up in both client and psychologist versions, providing a unipolar measure of session quality. The SES demonstrates high internal consistency for both clients (α = 0,87) and counselors (α=0,89)

[Lent, 2006]. Additionally, it has concurrent validity (r = 0,51, p < 0,001) with the SEQ Depth scale from the client's perspective

[Hill, 2002].

In contemporary literature, SES is generally applied to study the relationship between session quality and therapist’s self-efficacy

[Li, 2022], transference and countertransference

[Bhatia, 2018], therapist's emotional state

[Chui, 2022], impact of pre-session meditative practices

[Hunt, 2022], and immediacy in the client-therapist relationship

[Shafran, 2017] on session quality.

Low-quality sessions, according to SES, are characterized by dissatisfaction, worthlessness, and ineffectiveness, while high-quality sessions are associated with contentment, perceived benefit, and value.

As a brief and convenient tool, SES is suitable for routine psychological or psychotherapeutic practice, offering quick insights into session quality. However, its use for extensive research may be limited due to its singular overall indicator and a limited number of items.

Session Impacts Scale

The Session Impacts Scale (SIS) is a tool used in about 10% of recent session quality research (N = 6). SIS was created in 1994 by Robert Elliott and M. Mark Wexler and consists of 16 statements rated on a 5-point scale across three scales: Task Impacts, Relationship Impacts, and Hindering Impacts. It was developed based on content-analytical research on client-provided descriptions of significant therapy events. The scale categorizes therapeutic influence into helpful and hindering impacts, with helpful impacts further divided into task and relationship impacts

[Elliott, 1994].

The SIS demonstrates acceptable to high internal consistency (α = 0,67 to 0,92) and significant correlations with all SEQ scales. For instance, the Hindering Impacts Scale had negative correlations with Depth, Smoothness, and Positivity (r = –0,22, –0,24, and –0.31, respectively; p < 0,001)

[Elliott, 1994].

In contemporary research, SIS is mainly used to examine the correlation between session quality and factors such as countertransference

[Rocco, 2021], nonverbal behavior

[Naman, 2015], coping strategies and cognitive errors

[Antunes-Alves, 2014], gender differences

[Arora, 2022]. It is also used to compare the quality of sessions with a live psychotherapist and sessions with computer programs

[Gega, 2013].

The SIS can be used to evaluate individual significant events during a session and their impact on the client, allowing for a more in-depth and differentiated analysis compared to previous methods. It is designed to gather client feedback on session quality and initiate a discussion.

In 2023, the Session Reactions Scale-3 (SRS-3) and a brief version of the SRS-3 (SRS-3-B) were introduced as improved versions of the SIS

[Řiháček, 2023]. They incorporate data from recent meta-analyses that focus on the client's perspective of various processes during the session and place more emphasis on the client's active role in therapy and counseling. The inverse correlation between helpful and hindering reactions suggests that the SRS-3-B is feasible as a unipolar scale for session quality (α = 0,89).

According to SIS and SRS-3, low-quality sessions are characterized by hindering impacts or reactions, such as pressure, lack of guidance and support, feeling abandoned, misunderstood, uncomfortable, criticized, stuck, being more bothered by unpleasant thoughts, feelings, or memories, more confused about problems, and being worse off. Conversely, a high-quality session is one in which the client experiences significant helpful events and reactions that are related to the task and the therapeutic relationship. Task-related events and reactions may include gaining new insights about oneself or others, increased awareness of thoughts, feelings, or behaviors, a sense of progress in problem-solving and overcoming obstacles, greater clarity regarding goals or challenges, increased feelings of empowerment, hopefulness, or positivity, and the acquisition of new skills and coping strategies. Relationship-related reactions and events represent the client's feelings of being understood, supported, encouraged, protected, and closer to the therapist. These reactions can also lead to the client feeling relieved or less burdened and more engaged in therapy.

Both SIS and SRS-3 serve as valuable instruments for academic research and clinical application, offering a thorough analysis of session quality by examining client experiences. While SIS is a reliable tool that has been tested in many studies, SRS-3 is a more recent measure that has not yet been fully validated. The shorter SRS-3-B may be more suitable for practical use, allowing comprehensive feedback collection on session quality from clients.

Individual Therapy Process Questionnaire

Approximately 20% of the reviewed literature (N = 12) utilizes a separate set of methods for evaluating session quality based on Klaus Grawe's integrative theory of general factors and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy, known as Grawe's General Mechanisms of Change. Grawe's theory identifies five key mechanisms derived from numerous studies of the psychotherapy process [Grawe, 2004]: resource activation, problem actuation, mastery (coping), clarification of meaning, and therapeutic alliance.

In successful cases of psychotherapy, a specific relationship exists between resource activation and problem actuation. If the activation of resources exceeds the activation of the problem, there is a higher probability of a positive corrective experience and successful completion of psychotherapy

[Gassmann, 2006]. This has been confirmed by recent meta-analysis of strength-based methods

[Flückiger, 2023].

Contemporary research primarily employs K. Grawe's proposed mechanisms to investigate the association between session quality and interpersonal synchronization

[Prinz, 2021], drop-out

[Gmeinwieser, 2020], body-weight related sudden gains

[Brockmeyer, 2023], and to predict therapy outcome based on session quality

[Wrede, 2023].

Among the session quality assessment methods derived from K. Grawe's theory, the Individual Therapy Process Questionnaire (ITPQ) is considered one of the most recent and informative

[Mander, 2015]. Featuring versions for psychologists and clients, the ITPQ assesses 36 items across eight theoretical dimensions: resource activation, problem actuation, mastery (coping), clarification of meaning, emotional bond, agreement on goals and tasks, therapist interference, and patient fear. The ITPQ aligns with the SIS in considering therapeutic relationship quality, task-related factors, and negative session factors

[Řiháček, 2023].

High coefficients of internal consistency exceeding 0,8 were found for all scales, except for problem actuation (α = 0,73 and 0,76 for client and therapist versions, respectively) and therapist interference (α = 0,6 and 0,77 for client and therapist versions, respectively)

[Mander, 2015].

According to the ITPQ, a therapy session may be deemed low-quality if the therapist employs excessive pressure, causing the client to feel judged and embarrassed, displays emotional detachment, fails to recognize the client's efforts, and there are communication difficulties. In a high-quality session, the psychotherapist or psychologist demonstrates genuine care, emphasizes the client's strengths, intentionally utilizes their abilities, instills hope, teaches improved coping strategies, and facilitates progress in overcoming problems. The therapist improves the client's capacity to act, enables them to view problems in new ways, enhances their self-concept, and increases awareness of motives behind behavior. Both client and therapist share an emotional investment, appreciate each other, and agree on goals and tasks. The conducted activities are found useful, fostering mutual understanding and comfort in the therapeutic relationship.

The ITPQ provides a comprehensive evaluation of session quality, analyzing psychotherapeutic change mechanisms from both client and therapist perspectives. It is better suited for research purposes than for routine practice due to the amount of time required to complete it.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this article provides the first review of methods for evaluating psychotherapy and psychological counseling session quality. Currently, the most common approach in the field is to administer questionnaires after sessions. However, there is no single best method for evaluating session quality. Each instrument has strengths and limitations in terms of breadth and perspectives captured, as well as their research versus clinical utility.

The SES is the quickest instrument to complete due to its minimal number of items. The ITPQ, although the longest questionnaire, provides the most comprehensive information about session quality. The SIS (SRS-3) strikes a balance between the SES and the ITPQ by providing substantial information in a shorter time frame, making it a faster option than the ITPQ. Finally, the SEQ falls between the SES and the SIS in terms of completion speed, providing more information than the SES but less than the SIS.

According to the current literature review, high-quality therapy sessions are often associated with a trusting relationship between the client and the therapist. These sessions are characterized by depth, significance, value, comfort, and effectiveness as perceived by clients. Such sessions offer fresh insights and enhance self-understanding, illuminating aspects of their personality, challenges, and emotions. Additionally, clients report advancements in coping mechanisms and problem-solving strategies, fostering a sense of progress and empowerment. Clients commonly express satisfaction and gratitude toward therapists for creating a trusted space conducive to confiding.

During these sessions, specialists offer support, encouragement, acceptance, reassurance, warmth, and genuine care. They aim to instill hope, recognize and leverage client strengths, and dedicate effort to activating and enhancing resources. Professionals aid in reframing problems, exploring new perspectives, coping with challenges, and increasing awareness of behavioral motives. Importantly, therapists prioritize empowering clients over immediate issue resolution and avoid imposing actions against their will.

The results of the literature review are significant because they provide a better understanding of how to identify high-quality therapy sessions, including the assessment methods and key characteristics associated with such sessions. This promotes a more profound comprehension of the mechanisms underlying observed outcomes. It also helps psychologists refine their practice, understand the effectiveness of specific methods, and choose the most appropriate approach for each individual case. It facilitates adjustments during the therapeutic or counseling process, thereby increasing the likelihood of achieving desired outcomes. Furthermore, the aforementioned high-quality session characteristics can be used by mental health professionals as practical recommendations for improving the quality of their psychotherapeutic or counseling practice.

Nevertheless, it is unclear whether the listed characteristics of a high-quality session are exhaustive or if any relevant aspects have been missed. Therefore, future research should focus not only on methods for evaluating session quality but also on exploring theoretical advancements in the field that may not have been translated into practical assessment methods. Furthermore, it may be beneficial for studies to distinguish between the quality of psychotherapy sessions and counseling sessions, as these processes have distinct characteristics despite their similarities. In research, it may be more advantageous to use measures that consider multiple factors of session quality, such as the ITPQ, instead of relying on a single factor.

Conclusion

Session quality is a complex phenomenon that encompasses various factors related to the experiences and behavior of both the therapist and the client. Based on the literature review, four main methods for assessing the quality of psychotherapy and counseling sessions have been identified: the Session Evaluation Questionnaire, Session Evaluation Scale, Session Impacts Scale, and Individual Therapy Process Questionnaire. There is no single best method, as each one has its own advantages and disadvantages. High-quality therapy sessions require a trustworthy relationship between the therapist and the client. The therapist should offer valuable insights, assist in identifying strategies for overcoming challenges, and prioritize empowering the client while respecting their autonomy.