«Not only are social life and communication identical, but all communication is educational»

(John Dewey, Democracy and Education)

Foreword

Each educational programme which reflects the etymology of the term e-ducere, “to bring out”, “to awaken” and so on, will necessarily be based on observation of the other, their potential and needs. This assumption, and the crucial issues that follow, cannot be evaded when designing educational programmes within the detention system.

As has been rightly pointed out, «prison and re-education are not terms which can easily be reconciled [...]. What is certain is that those who originally conceived of punishment in essentially rehabilitative terms would never have made the prison term the keystone of the penal system» .

In fact, two levels overlap in the execution of a prison sentence: that of re-education and that of confinement-punishment. While the former requires the voluntary submission of the subject-person to a sort of therapeutic treatment, the second is based on coercion. But even if the rehabilitative aspect is the only aspect under consideration, it is true that we cannot ignore the attempts made by prisoners to «exploit the treatment kind of activities and practices of specialists in the psycho- pedagogical sector, in order to obtain the various benefits envisaged under prison regulations» . From this derives the importance of analyzing dialogical communication within a totalizing system such as that of the prison. The ability to communicate freely, or at least through multiple modes, is today perhaps one of the greatest of human freedoms.

The need to communicate, and thereby establish positive relationships, is inseparable, both in free society and in the context of total institutions such as the prison community. This is because of the proposition that «the human being grows and matures through relationality, dialogue, solidarity, and the presence of an educational community» .

This axiological dimension of pedagogy, as a “science of values”, finds expression in the criterion of individualization and re-education of the subject-person.

1. Levels of communication and learning tools

The penal institution is a complex system, in which the protagonists of human action (prison workers, teachers, volunteers, inmates, etc.) establish a set of relations which have meaning in terms of the global context of belonging. Education is not concerned only with the custodial environment, but also with the centrality of the person embodied in the individual detainee.

In this regard, it is important to note that «the element of connection between the individual and the prison context is essentially communication» . By the term communication, in the pedagogical sense is meant «the interaction between people, the exchange of social values, the con-division of meanings, social relationships, and beyond words also gestures, physical posture, facial expression, gaze and mimicry» . Dialogic communication, a priority feature of the educational relationship, has always constituted the basis on which relational dynamics are built, in every sphere of social life.

For man, and in particular for the detainee, human understanding is fundamental, which is approached mainly through dialogue. Colombero writes that «Man [...] is not only a being in the world, but is also in relationship with the world of objects and of people; the stages of his development as a person are defined on the basis of the quality and intensity of his relationship with the cosmos and with the community of his fellows» .

Consequently, re-education passes through the value of humanity which is transmitted to the prisoner through a specific relationship which Pati finds in human communication: «human communication, if it is established and conducted for training purposes, is in itself full of values» . Communication, in other words, becomes a strategic component to «analyze and understand the subject you are faced with, and for the reciprocal transmission of knowledge, values and feelings, thus giving sense and meaning to existence» .

In consequence, intersubjective communication belongs to the sphere of the concreteness and matter-of-factness of existence; «inscribed within the precise horizons of life, it derives not from demonstrations nor from systematic positions, but from fecund motivations, from principles which have subjecthood and are themselves freely» .

As Cambi rightly says, «praxis and language multiply, they emphasis communication until they render this world of symbols, rites, rules, structures, methodologies and social forms, all constructed from and for communication: our own specific world, the prevalent one for us also when compared to nature, to life and its codes» .

It is important to note that, within the penitentiary system the interview is considered one of the most significant contacts with detainees and internees: «it aims to identify the necessary solutions for individual problems or problems with the structure from the earliest interview on entry» .

The basic principle behind the birth of a real interview is that «both parties understand their interlocutor as this man, as really this man. I perceive his intimacy, and that he is different, essentially different from me, in this particular way, that characterises him alone; and I accept the man that I have perceived in such a way that, in all seriousness, I can address my word to him as he is in his essence. [..] Of course, it depends on him, at this point, if a real interview is to appear, and reciprocity become language» .

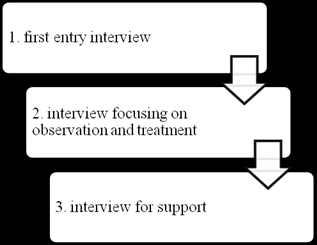

The forms of the pedagogical interview, dealt with by Law n . 354, 26 luglio 1975, are:

The first entry interview is carried out by the educator together with new detainees, and must be conducted within 24 hours of entry, generally following the medical examination: it aims to collect personal, family and judicial data, to be kept in a “personal file”, which will represent the main instrument for acquisition of all the documentation necessary to develop a treatment pathway . In many cases, attending the interview with the expert is not a free choice, but performed in response to a legal requirement, with obvious complications that risk ruining the already difficult relationship between educator and educated. This relation, which is already tense, between detainee and educator is thus transformed into a «complex game in which no-one wishes to reveal his cards: the detainee hides behind a multiplicity of defence mechanisms, the expert uses enigmatic communication» . In this way the probability that the interview will give rise to conventional communication with no value whatever is extremely great.

As Turco says, in fact, «what should be a relationship of help continues to be structured as one of control, above all in the eyes of the prisoner who is not the buyer of the instance»

In such a context, intervention for support consists in a «relationship of help» for the detainee, which may be activated by the educator, by the psychologist or by the chaplain. The very etymology of the word “support” contains the idea of “protecting”, “conserving”, “nourishing” the imprisoned subject who has an effective need to be supported, and often presents a fragile personality, often unable to supply himself with the elementary needs of his own ego.

According to Petrocchi «it is necessary to help the inmate become aware of his good and bad points, of the healthy and unhealthy tendencies of his character matrix ». These “unhealthy tendencies”, in the penal world, can be found in the destructive aggression of the inmate, both against others and himself.

Acts of self-harm frequently represent a desperate need for recognition of one’s own right to life, to be accepted and understood, and hence they are acts of vengeance against the lack of such recognition; «in order to escape from isolation, from the depersonalisation of the prison system, the inmate has a need for human comprehension that involves meeting, listening and dialogue» .

In this sense the relationship of empathy, which already has great importance in educational relations, must characterise the verbal and gestural communication with the imprisoned, above all with those at risk of committing acts of self-harm.

The empathetic relation with the other represents only the first phase of «awareness of one’s own self». In this sense, as Bertolini conclusively states «to understand the other with empathy means to be able to see, momentarily, the world from his point of view, it means to see the other just as he sees himself; it means, finally, to know how it feels to wear his clothes and hence adopt the frame that distinguishes his life» .

In this relational process, the spoken word acquires the typical significance of an «eminently personal communication: always, even the most banal messages are received as words spoken in trust; [...] they are, therefore, the words the educator, with his heart, directs to the heart of the learner» .

From this perspective the interview assumes, as Santerini says, a «value density», in other words it becomes a didactic communication, like a pedagogical relationship based on empathy, participation and relational closeness» .

In particular, to be able to intuit the moods and feelings of the subject, predict his reactions and understand another’s disappointments and frustrations; all this will help the subject to reconstruct a “positive self-image,” and will lead him to make plans thanks to the technique of “resilience” .

Goffman writes that: «when a subject notices that an observer is trying to discover his secrets and find unequivocal signs that provide him with an understanding of the subject’s intentions [.] the subject is able to use these imperceptible or unequivocal signs to convince the observer of whatever he wants him to believe» .

Instrumental communication is a very common practice in the penitentiary world, and because of this it is opportune that «all operators in penitentiaries must always keep in mind the conviction that, if the pedagogy of the word is important and useful, that of gesture is still more so, and that there is a moral duty to practice what one preaches» .

In the area of non-verbal communication, the various indicators to keep in mind are para-language (laughter, tears, voice intensity, silences) and cinesic components (facial expression, posture, gesture, “body language”). Other non-verbal elements of communication are clothes, the use of golden objects, refusal of food etc., and this would seem to suggest to the educator the importance of a sense of humanity and respect for the personal dignity of each individual .

It is important to underline that such “non-verbal” components have the fundamental importance of “protecting” the real identity of the detainee from possible intrusions; «to keep it intact until the moment when it will no longer be risky for him to express his own feelings, a moment in which he can realise himself only through renewed entry to society as a free man» .

The process of being prisonised already modifies the communication and interaction patterns of a man with himself and with others.

The “body” becomes the means with which the detainee can communicate, can express his own needs and attitudes; it assumes great importance when communication is represented by silence.

Non-verbal communication permits, in fact, the expression of the problems and frustrations of being detained; as Serra states «the channel of non-verbal communication allows the individual to safeguard his own individuality in face of the “de-personalisation” of prison» .

The interpersonal relationship which is initially central in thought and reflection may become a dynamic principle which «affects the features of communication in a singular way [...], purifies the teaching process, consolidates the actuality of the relation. And leads the communication towards essential themes of humanity and becoming human, themes which have a single concrete concept at their core: «we are talking about you» .

2. Pedagogical methods in a penitentiary context: the autobiography and communication about the self

Reflection on care of the self is particularly important when dealing with places, such as prison, in which trouble is a concrete daily condition. Such scenes reveal lifestyles and habits which leave permanent traces in body and mind, which transform the very meaning of words like “well-being” and “identity”: «hence, not just the detainees, but prison workers and other operators who enter these worlds experience the concrete human need to elaborate this uneasiness: for such agents the care of the self is not an optional luxury but a vital necessity» .

From a phenomenological point of view, trouble is «first of all an experience, and as such can be understood only starting from the subject’s own point of view».

The etymological origin of the term dis-agio (trouble) confirms the sense of something that is not, an emptiness, an absence. A single subject-person in the prison reality might tell us, if properly approached, what his trouble consists of, what are his troubling or troubled experiences from his point of view, if he has needs or desires, however frustrated. «Maybe he could also indicate possible pathways to re-discover the pleasures of desiring something beyond his simple needs, by listening to himself and by that interior education inextricably bound up with making sense of things» .

Any educator will not, or should not, consider trouble as an enemy to be fought against, but rather as a precious resource, an experience to question or to explore.

These premises are important to understand the very notion of cure, because «the remedy for trouble is care of the self, understood as listening to one’s own needs and desires, active comprehension of existence, reflection, balance and life plans» .

Cure is the expression of a will that has decided to rule over educational complexity, the implicit risks in formative processes, and the precarious nature of the human condition. «It is the assumption of a salvific commitment towards a subject to rear, protect, guide, orient and support [...]. It is the manifestation of a project which is a hypothesis for a future, open and dynamic, inspired by the utopia of emancipation, by liberty and social inclusion» .

From such a perspective, as Formenti conclusively argues, «the first essential, indispensable operation in order to speak of an autobiographical approach is to explain the concept of adulthood. In our culture an adult is one able to understand and act, to exercise his own citizenship, to speak for himself, as well as about himself» .

The stories of these people, in other hands, can become a mere legal dossier produced by an expert (psychologist, educator, social worker); and it is in this delicate passage that the activity of an autobiographical laboratory consists, whose aim is to stimulate narrative thoughts in the pupils, the study of themselves and their own interior worlds, the revisiting of their own life histories and the reconstruction of their own identities.

The general objectives pursued when using an autobiographical technique are:

- To stimulate the capacity to express thoughts and feelings;

- To reflect on the significance of one’s own life experiences;

- To stimulate self-awareness and reflection for personal development;

- To increase awareness of the self and construction of one’s own identity;

- To increase self-respect and trust in oneself .

The implicit pedagogic nature of autobiography consists in helping «the other, or oneself, in the process of introspection, the memory of the self, not as a simple “memory”, but as unitary reconstruction, which allows for appreciation of those nodal points to which a value, a sense, can be given » . To tell stories, to narrate and disclose represents a way of meeting oneself, a trip to the centre of one’s own being, which allows the subject to contact his own mental states, his fears, desires and needs.

The autobiographical method, therefore, helps one to reflect on one’s own life history and on the relationships one has with others. «It is an introspective method, a sort of personal diary, which allows one to order one’s own thoughts and to re(find) one’s own lost or denied identity» .

As an example of the educative autobiographical method, we print a text produced by certain detainees of the Casa Circondariale Bicocca of Catania during the Transnational Grundtving Seminar, held on 6th May 2012:

«Today I live in a house that is not mine, that smells of iron and has no flavour, and I don’t know the people very well. There are no photos on the walls, and I live leaning up against these walls».

«If I was an object I’d want to be a suitcase, because you need one to carry clothes on a journey, and I want to get away from here ».

«I would rather be a stone that has always existed and has witnessed the birth of the world».

«I would be a fine clock because I like to be handled with care».

«I would just like to be a nothing».

«I am a person who hopes to be going home soon» .

In front of the condition of solitude of prison life, the subject finds himself alone with himself, and in order not to get lost or alienated from himself, must activate his own resources, in such a way as to «reconstruct the invisible internal space which will become the place for personal cure» .

Beyond the narrative methodologies it is necessary to consider, in every educational relationship or of assistance, that the foundation of the meeting is not in knowing what to do but rather in knowing how to be. The specialists must believe in the usefulness of the project, but it is necessary above all that they know how to live it, because «to know how to live a technique is much more complex than knowing how to use or introduce it. A technique is always a “thing”, an object, a means, used for an end, but if the technique stops there it will not serve much good. Techne means art, and art is not only skill, or competence in doing something. It requires a special ability for “concentration”, “anxiety”, for continual “research”» .

The mechanisms for reconstructing stories, for symbolically inventing new ones, entering into relationships with them, require a favourable situation. A laboratory activates a specific modality in its procedures, an active modality that is «composed of concrete elements and cultural references; of an intimate dialogue between participants and of openness towards an enlarged social dimension» .

Enthusiasm and curiosity are necessary to discover the eternal game of the unique personal stories which become universal, while the universal ones produce their echoes in single individuals, and hence in the particular; in this sense «a prison educator may find an increase in optimism and protection from the risks of burn out in narrative work, as well as other opportunities to reflect on past choices and find new pathways and points of view» .

Conclusions

Each detainee comes with his own life history, often characterised by a long, enforced period of emargination, from situations of extreme difficulty in adapting.

A dominant note in many of these stories is a sense of impotence, which judicial and penal mechanisms only augment, and in this perspective «the institutionalised subject carries with him his whole world, to be substituted eventually, bit by bit, by memory of it» .

The details of the individual’s story “before incarceration”, the collection of actions and events that constitute the prisoner’s daily round, the different assumptions about life that represent the “after prison” may become, during the period of treatment, dialogical content which may be activated during educative communication. That is to say, they represent concrete «starting points for a life narrative which creates awareness of personal resources and capacities that need activation in order to capture the existential value of the life experiences of the person» .

Narration, telling oneself, quickly become a means of reasoning about oneself and the world, a «philosophical tool that aims to find once more, through singularity, the universal dimension and the sense of human life» .

By writing himself, «the narrator notices that he will never reach an essence or an ultimate security, but that in this debate the imagination will compensate for the void. Where the narrator is able to reveal himself to himself only in the plurality of his actions and the cognitive processes that self-produce him, that reveal to him his own complexity» .

Thus the story of the educative relation is constructed, a story composed of moments and occasions, of evolutions and involutions, of complex and sometimes contradictory emotional events.

The use of educational modalities based on the recovery of error for formative purposes leads the detainee gradually towards «the autonomous substitution of motives of deficit for those of growth. In contrast with models which reduce responsibility, it confers a positive significance on the proposed formative itinerary».

It follows that to educate means not only to find a meaning in the actions and attitudes of another person, but also to arrive at a goal: «the educative action is the transformation of reality itself through the educated person».