Introduction

Adolescence is a period of development and self-consolidation specific to the second decade of life (Steinberg, 2014) and is recognized as critical for psychosocial development (Meeus, 2016). At the same time, school becomes a process of socialization during which the adolescent becomes more and more aware of external perspectives, perspectives coming from teachers or other social influences (Choudhury et al., 2006). The maturation process is then consolidated with the help of interactions between people and the social contexts surrounding the adolescent (Meeus, 2016). To achieve an identity of their own, the adolescent needs to feel understood and respected. This process can occur through positive, secure and stable relationships (Anderson et al., 2004) with a competent adult who may be outside the family nucleus. This kind of relationship has been shown to be an important resilience asset in adolescents regardless of their risk status (Anderson, 2004). For many adolescents, these relationships are formed at school with a staff member such as a teacher. Despite the fact that the relationships created differ from one teacher to another (Roorda et al., 2019), the results of Yu et al., (2018)’s study show that key interactions between teacher and adolescent appear to meet the developmental needs, such as autonomy, competence and connection, of adolescents. It goes without saying that learning-based relationships are different from interpersonal relation-ships, but according to Tobbell and O’Donnell (2013), the latter are a prerequisite for learning relationships. In addition to studying the quality of relationships between teachers and students, especially at-risk students, it is important to study the attitude and belief that teachers have towards the success of their students (Davis & Dupper, 2004). These facts are important to consider because, in Quebec, a pre-pandemic longitudinal study reveals that 35% of adolescents responded that they had a low level of sense of belonging to their school, while almost 20% felt that they had a low or medium level of social support in their school environment (Quebec Health Survey of High School Students 2016—2017 (QHSHSS), 2018). So, if teachers and the school community members work to strengthen student-teacher relationships, considerable improvements will occur in student motivation, engagement and performance (Dore-Cote, 2007; Scales et al., 2020). School also provides students with the possibility to develop relationships with peers, relationships that are crucial for the development of adolescents’ identity. Whether they are developed through interest-based groups, group projects or extracurricular activities, these relationships help teens to stay connected to school and facilitate their understanding of who they are as learners. Without those, young people can feel more anxious and more isolated (Hill & Steinberg, 2020 cited in Boudreault, 2020).

During this adolescence period, the family can naturally play a role in influencing the psychosocial development of the adolescent. The results of another longitudinal study involving the participation of more than 500 16-year-olds demonstrate the benefits of a constant and predictable family environment for healthy development and suggest that family routines, although little studied, are an important factor in long-term adolescent development (Barton et al., 2019). In Quebec, 31% of adolescents consider that they have weak or moderate social support in their family environment (QHSHSS, 2018). However, Deslandes’ numerous studies (see Deslandes, 2020) carried out with a large number of adolescents in Quebec have highlighted the crucial role of parental practices including supervision, time management and emotional support with regard to the success and development of young people. Parents are at the front line of the management of their adolescents’ daily routines also outside their regular school hours: sleeping habits, time spent on social media and videogames, as well as paid part-time jobs. In Quebec, 34% of adolescents sleep less than the recommended time which vary depending of the age group (QHSHSS, 2018). According to CEFRIO (2019), for the group aged from 13 to 17 years old, 39% spent more than 11 hours per week on electronic devises and 26% go over the recommended time which is 2 hours a day. In general, it appears that mothers are more sensitive and warm-hearted (engagement dimension)-than fathers and they participate more in the adolescents’ schooling (Deslandes, 2020). In Quebec, a high parental supervision is associated with school success (Deslandes, 1996).

In March 2020, teenagers in Quebec suddenly found themselves confined to their homes following the closure of schools due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Unlike natural disasters, responses to pandemics encourage isolation, separation and quarantine (Sprang & Silman, 2013). Ruptures of relations, loss of reference points, disruption of routines. Despite the fact that we have lived through the H1N1 and SARS pandemic, studies reporting the effects of human disasters or confinement in young people are limited. The incidence of post-traumatic shock and depression in adults following the SARS pandemic in Canada has been found to be similar to that following natural disasters and terrorism (Hawryluck et al., 2004).

The results of a cross-sectional study examining individual and family turmoil among young people in grades 4 to 12, 6 months after the September 11, 2001 attack, show that factors such as a parent’s job loss, regulated parental travel, and school closures were associated with higher rates of post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety disorder, and depression (Comer, et al., 2010). In addition, mental health problems as listed above, in addition to sleep disturbances in 9-18 years old, were assessed to persist for three years following the Ya’an earthquake in China in 2013 (Tang et al., 2018). In contrast, a questionnaire-based study of over 10,000 adolescents aged 15 and 16 in Norway found that the teacher-student relationship was a potential mechanism to reduce negative associations between mental health problems and noncompletion of high school.

The closure of Quebec schools in March 2020 also brought about a change in the way young people learn. In September 2020, after an improvement in the sociosanitary situation, all secondary school students attended school in person, at least for next couple of weeks, depending on the evolution of the pandemic. Rapidly, it deteriorated and the conditions varied according to school levels and geographic regions. The teens suddenly found themselves faced with another challenge. Although distance and hybrid learning in high school has been poorly studied (Turley & Graham, 2019), Stark (2019)’s findings have shown that distance learning students had a lower level of motivation compared to regular class students and was correlated with performance in the course and not necessarily with learning strategies.

Theoretical Frameworks

We begin with the external structure of Epstein’s model consisting of three spheres representing the main contexts in which children and adolescents learn and develop: family, school and community, whether or not intersected according to the following four forces: time, i.e. age, school level and social conditions at the time (force A), family characteristics, philosophies and practices (force B), school (force C) and community (force D). Some practices are carried out separately and others jointly. All the links between educators, parents and the community in the same living environment and between different contexts can be represented and studied within the framework of Epstein’s model. Deslandes (2020) has used this model as a lever for integrating a sociocultural approach to examine the links between the

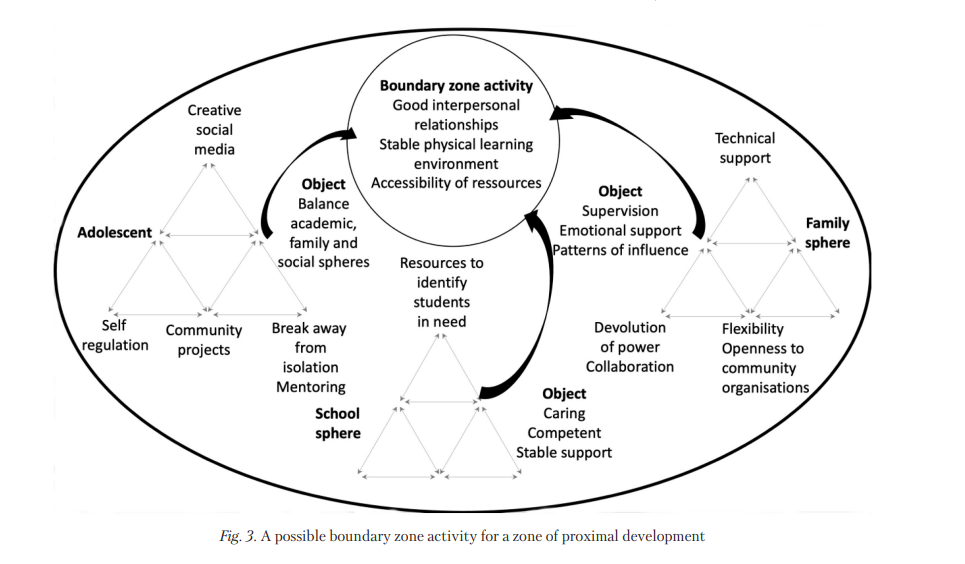

characteristics of students, families, and teachers based on collaborative school-family relationships as well as their values, beliefs, and expectations. In this paper, we push further and integrate the interrelated elements of Epstein’s model in a more systemic way. The contextual and systemic aspect of the reality of adolescence takes on all its importance when situated at the heart of an activity system hit by COVID-19. “The concept of ‘‘activity’’ as mediating between the individual and the social dimensions of human development originated from Vygotsky’s proposal of human action mediated by psychological tools as a unit of analysis of the individual’s higher cognitive processes” (Liang, 2011, p. 313). Grounded in cultural historical activity theory, Engestrom (2015) created a systemic model integrating the socioinstitutional infrastructure of the activity, namely, rules, the division of labor, and elements of the community and is referred to as second-generation CHAT, building on Leontev’s work. Although these elements delineating an activity system may presumably be considered separately, they must be interpreted as being interconnected. The pursuit of an activity aims at the transformation of a given environment and this activity is oriented towards an object such as the adolescent’s learning during the pandemic. According to activity theory, the introduction of new elements, such as COVID-19, is accompanied by a questioning of the rules and the division of labor of a community that regulates the adolescent’s learning. When recurrent tensions in the form of inner contradictions are identified, the lens of the triangular representation helps understand the systemic dimension of the individual|collective level of communication and organization (Engestrom & Sannino, 2013). Several factors affecting adolescence are likely to create tensions in teens’ daily life and interrelations with others (Barma et al., 2017). These elements could include modifications related to the rules and routines of their daily life, modifications of the relationship with the teacher as well as modifications with regard to the tools proposed by the teacher and mobilized by the young people in the act of learning. The adolescent is not acting alone but interacting with other significant school community members (school sphere) who are key actors in his learning activity. When two or more activity systems are interacting, they form a network of interacting systems. In third generation CHAT or expansive learning, a possible zone of proximal development takes place between activity systems and when a collective motive is shared, boundary crossing can lead to the development of the object of the activity. Figure 1 presents a network of activity systems.

In light of the contradictions identified, this study will circle how boundary crossing could happen between the school sphere and the family sphere to help the adolescents’ efforts to adapt to disruptive conditions brought by the pandemic and do their best to engage in learning.

Project and Research Objectives

This project aims to better describe the experiences of Quebec adolescents following confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 and their return to class in September of the same year. In short, we propose to identify the zones of tensions experienced by adolescents when COVID-19 forces them to redefine their relationship to family life, learning and school: mediation tools to their learning activities (online learning, hybrid mode, etc.), spatio-temporal redefinition of their activities (ergonomics, systemic understanding), modification of relationships with significant adults for them (parents, teachers). These tensions, if identified could help us better understand the impact of COVID-19 on the learning activities. If unresolved, they could indicate recurrent internal conflict situations for adolescents.

More specifically, this project aims to:

1. Highlight the tensions with relation to the adolescents’ perceptions during COVID-19 regarding:

a. their adjustments and routines;

b. their state of mind;

c. their relations to their peers, their teachers’ and their parents’ personal and family situation and their support.

2. Suggest individual and collective mediating avenues to better support adolescents’ learning activities and their parents’ and teachers’ collaboration having the potential to put in place a zone of proximal development.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were secondary level students registered in Quebec high schools in September 2020. Public and private schools from French and English school boards were included in the study. The sample size calculation for our descriptive-level research project was 385. This sample size is based on a statistical margin of error of 5% at the 95% confidence level (Bartlett, 2001).

Instruments

The quantitative survey used were largely inspired by the measurement instruments translated, validated and then used in several research studies by Deslandes and her team (see Deslandes, 2020). The questionnaire developed was available online on an open source survey software (LimeSurvey). The 52 questions explore the objectives described above. More specifically, the questionnaire is divided into 4 parts:

1. Characteristics of participants and their families (e.g., socio-demographic data)

2. Physical and school organization (e.g., work tools, time management)

3. Perceptions of the school environment (e.g., school schedule, extracurricular activities)

4. Relationships with parents, teachers, school stakeholders, and friends (during confinement and following return to school)

The validity of the questionnaire was assessed by 16 students who completed it as a pre-test and ensured the clarity of the questions. Some adjustments were made after the analysis of the student’s comments.

Procedures

Emails were sent to all high school principals asking them to share our study information sheet with the parents through emails or their newsletter. If parents accepted through passive consent, then they could share the link of the questionnaires with their adolescents. By reading the introduction to the questionnaire, the adolescent was able to learn about the objectives of the research project and his role as a participant. He had then the opportunity to proceed to the questionnaire if he agreed to participate in the project or to leave the site if he refused. The answers to the questions were anonymous and voluntary and the consent, explained in the introduction, was implicit by clicking to the first question of the survey. The answers to the questionnaire were compiled and recorded on the Lime Survey platform. The project was approved by the Laval University ethics committee (2020-286/28-09-2020).

Following data cleaning, quantitative analyses were done by first conducting descriptive analyses for each variable, such as frequencies, percentages and histogram generation. Then bivariate analyses were performed to examine associations between certain variables (e.g., school cycle, family status, gender, etc.). Finally, independence and strength of association analyses showed the existing associations with the use of chi-square and Cramer’s V. Documented tensions were delineated in emerging activity systems and possible avenues to put in place a zone of proximal development.

Results

To keep in line with the research objectives, results focus on data that reflect tensions to provide a clearer picture of the impact of COVID-19 on the adolescent learning conditions. Invitation emails were sent to 598 schools’ principals starting in the week of November 19th, 2020. Two French school boards and two English ones required an application before contact could be made directly to the schools. Applications were completed and submitted to three of those school boards however, due to the cost of the last one, the application for one of the English school board was put on hold. We received our first completed questionnaires on November 19th, 2020 and the survey was closed on April 3rd, 2021. After data cleaning, a total of 1057 adolescents, from 37 schools, completed the questionnaire and of those, 929 questionnaires were answered in full and 128 were partially completed because the teenagers stopped the questionnaire before the end. Due to the exploratory goal of this research, the descriptive analyses included the fully and partially completed questionnaires.

The characteristics of our participants and their family are showed in Table 1.

The majority of the participants are Quebecers, Francophones and have parents well educated. More than half attend regular school programs and live with both their parents. A good majority of mothers and fathers have a fulltime job. Interestingly, their situation changed during COVID-19: a greater proportion of mothers and fathers ended up with a higher rate of part-time jobs.

Table 1

Sociodemographic characteristics of participants and their families

|

Characteristics |

n |

% |

|

Gender |

||

|

Girl |

626 |

59.2 |

|

Boy |

405 |

38.3 |

|

Other |

26 |

2.5 |

|

Age |

||

|

less than 13 years |

341 |

32.3 |

|

14—15 years |

430 |

40.7 |

|

more than 16 years |

285 |

27 |

|

Ethnicity |

||

|

Quebecer or Canadian |

926 |

87.6 |

|

Other |

131 |

12.4 |

|

Language of study |

||

|

French |

1048 |

99.1 |

|

English |

9 |

0.9 |

|

Program of study |

||

|

Regular |

704 |

66.6 |

|

Particular program |

314 |

29.7 |

|

High school diploma |

16 |

1.5 |

|

Other |

23 |

2.2 |

|

Family structure |

||

|

Both parents |

709 |

67.1 |

|

Other |

347 |

32.9 |

|

Education level of father |

||

|

Primary and a few years in high school |

110 |

10.4 |

|

High school diploma |

238 |

22.6 |

|

College or University |

504 |

47.8 |

|

Don’t know or not applicable |

202 |

19.2 |

|

Education level of mother |

||

|

Primary and a few years in high school |

48 |

4.6 |

|

High school diploma |

178 |

16.9 |

|

College or University |

663 |

62.9 |

|

Don’t know or not applicable |

165 |

15.6 |

|

Father’s employment before the pandemic |

||

|

Unemployed |

32 |

3 |

|

Part-time work |

69 |

6.6 |

|

Full time work |

874 |

83.1 |

|

Other |

77 |

7.3 |

|

Father’s employment since the pandemic |

||

|

Unemployed |

77 |

7.4 |

|

Part-time work |

102 |

9.8 |

|

Full time work |

769 |

73.7 |

|

Other |

95 |

9.1 |

|

Mother’s employment before the pandemic |

||

|

Unemployed |

66 |

6.3 |

|

Part-time work |

119 |

11.3 |

|

Full time work |

787 |

74.9 |

|

Other |

79 |

7.5 |

|

Mother’s employment since the pandemic |

||

|

Unemployed |

100 |

9.6 |

|

Part-time work |

131 |

12.5 |

|

Full time work |

719 |

68.8 |

|

Other |

95 |

9.1 |

Adjustments and Routines

Adjustments regarding physical localisation of learning, resources availability and frequency of homework had to be made in COVID context. When it comes to physical localisation of learning at the time of the completion of the questionnaire, 52% of all respondents attended school everyday, 34 % only a few days per week, and 14% stayed home every day. In terms of resources available to the adolescents, 36% declared not having access to a quiet space to study or attend their classes on line, 19% didn’t have access to a computer on a regular basis. As for the frequency of homework, 48% of students declared doing homework less often than they did before the pandemic.

However, of all participants, 49% played videogames more than 3 hours per day and, 51% spent more than two hours a day on social media and 50% reported engaging in less than one hour a day or not at all in physical activities and interestingly. Of those who were playing videos games and were active on social media, 16% of the adolescents spent more than 4 hours a day on video games and also more than 3 hours a day on social media. 62% of girls reported being active on social media compare to 38% of boys (X (2, 968) =49.73, p <.001, Cramer’s V=0.23).

As can be seen in Table 2, for sleeping habits, 42% of respondents slept fewer than 8 hours per night. Of those who are playing video games more than 4 hours a day, 52% sleep less than 8 hours compare to 36% who play less than 3 hours per day. Among the group that spend more than 3 hours a day on social media, 55% sleep less than 8 hours while 21% of the adolescents that do not use social media sleep less than 8 hours. When asked about part-time work, 29% of our respondents declared having a part-time job. Of the teenagers who work more than 16 hours per week, 64% sleep less than 8 hours while 42% of those who work less than 11 hours sleep and 38% of those who do not work sleep less than 8 hours.

State of Mind

Of our participants, when asked how they felt in general during that time of COVID-19, 59% were sad and 82%, bored. Nearly 57% declared that COVID negatively impacted their school success while 24% said they didn’t understand the subject matter being taught. When looking at elements that seemed to affect their will to do their best at school, 42% attributed it to the changes in their routines, 55% missed school and 65% declared lacking motivation towards their school work.

Perceptions of the Adolescents with Regard to their Relations to their Peers, their Teachers’ and their Parents’ Personal and Family

Situation and their Support

When asked if they were happy to meet their friends again at school in September 2020, 86% of them responded positively while nearly 30% were not really happy to meet their new teachers. Since the beginning of the pandemic, 33% of adolescents did not think that at least one teacher was concerned about them. In the same line of thought, 21% did not think that at least one teacher was preoccupied by their learning progress. Likewise, 20% did not believe that at least one teacher was understanding and 37% thought that their wellbeing was not important in the eyes of many teachers. When comparing the situation before and during the pandemic, among the adolescents who said they felt close to at least one teacher at school, 47% did declared they did not remain in touch with at least one teacher they appreciated.

About their family relationships, 68% of the adolescents felt that their mother’s stress increased since the pandemic while 56% thought the same about their fathers’ stress (X(1, 736) =187.35, p <.001, ф=0.50).

Table 2

Frequencies and Chi-Square Results for Sleeping Hours in Hours of Activity

|

Sleeping hours |

<8 hours |

8—9 hours |

>10 hours |

X2(6) |

Cramer’s V |

|||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|||

|

Work (n=1053) |

||||||||

|

do not work |

287 |

38.4 |

409 |

54.8 |

51 |

6.8 |

27.4*** |

0.11 |

|

<11 hours |

66 |

41.8 |

80 |

50.6 |

12 |

7.6 |

|

|

|

11—15 hours |

49 |

57.6 |

35 |

41.2 |

_ 1 |

_ 1 |

|

|

|

>16 hours |

40 |

63.5 |

22 |

34.9 |

— 1 |

|

|

|

|

Video games (n=1054) |

||||||||

|

does not play |

47 |

42.7 |

54 |

49.1 |

9 |

8.2 |

19.75** |

0.1 |

|

<3 hours |

155 |

36 |

245 |

56.8 |

31 |

7.2 |

|

|

|

3—4 hours |

92 |

40.5 |

124 |

54.6 |

11 |

4.8 |

|

|

|

>4 hours |

148 |

51.7 |

124 |

43.4 |

14 |

4.9 |

|

|

|

Social media (n=1054) |

||||||||

|

does not use |

13 |

21 |

39 |

62.9 |

10 |

16.1 |

63.78*** |

0.17 |

|

<2 hours |

147 |

32.6 |

270 |

59.9 |

34 |

7.5 |

|

|

|

2—3 hours |

109 |

48.4 |

111 |

49.3 |

5 |

2.2 |

|

|

|

> 3 hours |

173 |

54.7 |

127 |

40.2 |

16 |

5.1 |

|

|

**p<.01, ***p<.001.

When asked the questions if they agreed with their parents being worried to leave them alone when they had to study from home while their parents were at work, 72% agreed that neither their mother nor their father were worried, while 15% thought only their mother was worried compared to 2% who thought only their father was worried (Table 3). About supervision of school work, 34% of the adolescents said that none of their parents supervised their work while 25% said only their mother compare to 4% who said only their father. Of all adolescents, 25% said that neither their father nor their mother both their parents keep an eye on their comings and goings while 16% thought that only their mother did compare to 3% who thought only their father did. When discussing supervision of daily routines, 26% said that neither one of their parents supervised them whereas supervision was done by the mother for 20% of respondents compare to the father for 3% of the respondents

Adolescents’ perception of their parents’ emotional support is presented under the angle of encouragements, sincere congratulations and openness to listen to their troubles and worries. Most of the adolescents said that they could talk about their troubles and worries with both their parents however, only 8% of the adolescents said that they could not to talk to neither their mother or father. 18% said that they could talk only to their mother while 4% said that they can talk only to their father. When having a problem, 8% said that they could talk only to their mother, 4% said that they could talk only to their father and 3% said that they could not talk to neither of them. When asked if they were congratulated for their achievements, 12% said that they were only from their mother, 2% only from their father and 4% did not receive any. Finally, of all the teenagers who answered when asked if they received encouragements about their school activities, 12% said that they received some only from their mother, 3% said only from their father and 5% didn’t received any encouragements.

Discussion

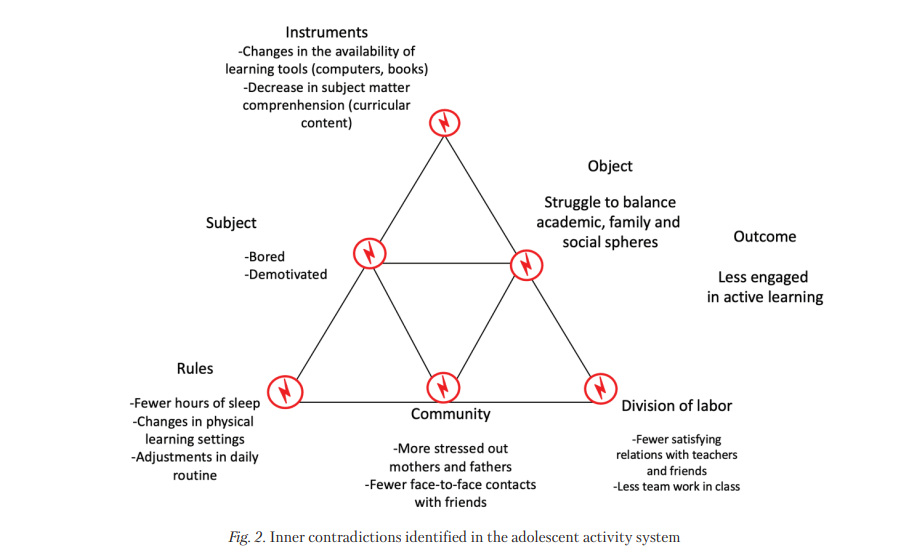

This section presents specific findings that help understanding the emerging tensions in the form of inner contradictions at the poles of the adolescent activity system with relation to their perceptions during COVID-19 regarding: their state of mind, their relations to their peers, their teachers’ and their parents’ personal and family situation and their support their adjustments and routines (see Figure 2). To do so, we purposely focused on the findings that evoked possible clashes with situations that existed during COVID-19.

Systemic Analysis of the Adolescent’s

Activity System

Our attention focused on a systemic analysis of the adolescent’s activity system engaging in learning during the pandemic in order to pinpoint a possible zone of proximal development with other activity systems such as the school one and the parents’ one. First, we focus on the adolescents’ activity system. Figure 2 illustrates reported tensions at each pole (inner contradictions) of his/her activity system during the pandemic.

The adolescents declared an important decline in their motivation during COVID. As for their state of mind, a great majority said that they felt sad and missed their friends. Half of them said they did not miss going to school. After the period of confinement (March 2020 — September 2020), when they actually returned to school face to face, a third of them were not really happy to meet their new teachers and they questioned the caring expected from their teachers. Moreover, almost half of the adolescents declared that they did not remain in touch with at least one teacher when they were confined. A quarter said that they did not understand the subject being taught. As for relations with their families, the adolescents said that their mothers and fathers were more stressed out during the pandemic. It is well known that an increase in stress is likely to lead to more misunderstanding within the family relationships and affect parental practices. For instance, some adolescents revealed that they could not rely on either one of their parents when having problems. A small percentage declared not receiving affective support regarding their schooling, mainly from their father.

The usual object of the activity of learning adolescents attending middle of high school is to find a balance between their school work, sleeping hours and leisure activities, including videogames and use of social media. In general, a daily routine normally comprises five hours of instructional schooling in Canada. The rest is gener-

Table 3

Frequencies and Chi-Square Results of Adolescents’ Perceptions for Parental Support and Supervision

|

Parents |

Mother only |

Father only |

Neither |

X2(1) |

Ф |

|||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|||

|

Worry when I am alone at home (n=623) |

95 |

15.2 |

12 |

1.9 |

450 |

72.2 |

160.71*** |

0.51 |

|

Supervise my school work (n=744) |

185 |

24.9 |

28 |

3.8 |

250 |

33.6 |

180.91*** |

0.49 |

|

Supervise my outings (n=712) |

112 |

15.7 |

21 |

2.9 |

178 |

25.0 |

271.53*** |

0.62 |

|

Supervise my routines (n=725) |

142 |

19.6 |

20 |

2.8 |

186 |

25.7 |

235.74*** |

0.57 |

|

Encourage me in my school school activities (n=897) |

103 |

11.5 |

29 |

3.2 |

45 |

5.0 |

114.95*** |

0.36 |

|

I can talk about my worries (n=770) |

135 |

17.5 |

31 |

4.0 |

65 |

8.4 |

99.35*** |

0.36 |

|

I can count on my parents (n=805) |

62 |

7.7 |

30 |

3.7 |

25 |

3.1 |

73.52*** |

0.30 |

|

Congratulate me (n=904) |

107 |

11.8 |

22 |

2.4 |

35 |

3.9 |

95.94*** |

0.33 |

***p<.001.

the previous activities. First, there was a change in the physical localisation of schooling based on the unpredictable sociosanitary situation: constant back and forth between face to face and online learning. Not all students had access to a computer at home and a third declared not having access to a quiet place to study. Almost half of them said they did not do their homework as expected. Likewise, they slept less than the eight hours per night recommended, especially the videogames players who dedicated more than four hours a day to play and adolescents active on social media more than three hours a day. One third of the students had paid jobs which, according to QHSHSS (2018) represents an increase compared to pre COVID situation (7%).

A decrease in motivation and the loss of references points at school, within the family and with friends might weigh on the adolescent’s capacity to engage fully in his/ her learning tasks as well as his/her general well-being.

Suggested Individual and Collective Mediating Avenues to Better Support Adolescents’ Learning Activities and their Parents’ and Teachers’ Collaboration: A Possible Boundary

Crossing Zone

In light of the zones of tensions identified, promising avenues are considered to better support the adolescents during these challenging times. Many parents cite technology as a reason why parenting is harder today than in the past, even before COVID-19. Conflicts are likely to have increased in family settings during the pandemic. In order to prevent power struggles and control issues, involving directly the adolescents when establishing routines and schedules (leisure time and academic time) would be a good idea. Parents should be open to a more flexible schedule when it comes to teenagers’ difficulty to concentrate early in the morning when attending classes. When online, teachers should also be more sensitive of the attention span of their students. Nevertheless, social media can act as a promising tool if not restricted to a passive leisure activity. During pandemic time, school could propose group projects using social media in order to engage students with other friends to prevent isolation (oral presentations, music groups, chess competitions). Another promising avenue would be for schools to ensure they have enough human resources to identify adolescents in need and put in place mentoring programs. As for parents themselves, they would benefit from technical support to connect better with the teachers in the context of online learning as well as enhance their understanding or their adolescent’s reality. The possibility for teachers to phone home when needs are expressed by parents or teenagers is a positive action to take. To help lower their sense of isolation and empower the adolescents, members of the local community could be creative and inform the adolescents about people in need and encourage them to contribute to a collective effort (environmental projects, help to the elderly, community gardens while respecting the sociosanitary measures). Figure 3 illustrates positive avenues to be taken by individual|collective acting in three activity systems so a boundary crossing zone is formed for the benefit of the adolescent.

Conclusion

Our research provides an improved comprehension of the impact of COVID-19 on adolescent’s efforts to balance disruptive changes to their routines and its impact on their state of mind, relationships with their parents as well as their perceptions of teacher’s caring. Combining elements coming from the family and the school spheres, the descriptive and systemic analysis of the questionnaire data allows a holistic understanding of the adolescent’s new learning conditions. Findings put into evidence the tensions in the form of inner contradictions identified at the poles of the adolescent activity system: sadness, demotivation, disruption on their daily routines and loss of reference points when it comes to their learning settings. Access to a quiet space and to a computer is not for all of them. Their sleep is affected and many get less than needed. Several are engaged in paid jobs and they spend time on video games and social media. They also think that their parents are more stressed out. Many parents experience job insecurity. The adolescents report not always getting emotional support from them. The students miss their friends but not their teachers as much.

This is a challenging time and research is ongoing. Data make it possible to suggest avenues that are relevant and realistic to create a boundary activity zone for the benefit of the adolescent: more flexibility on all parts, more clever use of social media, more technical and human resources to support students and families. In order to balance their academic and leisure time, the adolescent needs to self-regulate and break away from isolation in the best way proposed by their school and family spheres.

[Anderson] Due to the small number of people, the results cannot be released.