Introduction

Personal and professional characteristics of teachers have come to the forefront in both theoretical and applied research [Dyshlyuk; Mitina, 2022]. A special focus, in this regard, is given to the analysis of values and meanings underlying teachers’ professional activity [Ansimova, 2022]. Thus, it is expedient to explore the relationship between professional dispositions and competencies of inclusion teachers.

The first research into the professional and personal development of teachers appeared in the 1980s. It was led by L. G. Katz and J. D. Raths, who highlighted the relationship between the teachers’ dispositions and the development of their professional competencies [Katz, 1985].

First, this approach is in line with the modern understanding of the phenomenological nature of professional disposition. It is seen as a certain personal meaningful basis for building a strategy to achieve professional goals. According to I. V. Abakumova and N. A. Savchenko, professional disposition interacts with the motive of actual activity, while preserving its own stable meaning capable of generating additional specific intents. Therefore, professional dispositions as such can ‘influence professionally-oriented training and, likely, future professional activity, as a mediated mechanism that shapes a professional strategy’ [Abakumova, 2008, p. 30]. On the one hand, professional dispositions as a set of a teacher’s values, commitments and professional and ethical norms influence the teacher’s interaction with other stakeholders in education. They also have an impact on learning, motivation and development of students. On the other hand, professional dispositions correlate with teachers’ professional development [Martin, 2022]. Hence, professional dispositions comprise one of the criterion aspects of qualification assessment of future teachers [Saltis, 2021].

Secondly, the approach proposed by Katz and Raths emphasizes that teachers’ dispositions should be explored along with the development of their professional competencies. This approach fits in with the current perspectives on the inseparable nature of teachers’ professional competences and the fundamental meanings of teaching. Y. V. Senko and M. N. Frolovskaya aptly argue that, ‘the limitations of professional competence reveal themselves as soon as we touch upon the sphere of meanings of teachers’ professional activity’ [Senko, p. 128]. This perspective highlights the importance of dispositions for effective teaching. From this standpoint, it is reasonable to consider the development of professional dispositions that support competency in the educational process as an essential content-focused and goal-oriented aspect of teacher training [Wiesman, 2023; Wolff, 2023]. Specifically, it is desirable to encourage self-reflection on common professional dispositions [te Poel, 2023]. The optimization of dispositions in working teachers will enhance their performance [Strom, 2019; Wolff, 2023] and help overcome the limitations of professional mobility [Persson, 2022], etc.

Moreover, as inclusion has become increasingly prevalent in education at regional, national, and international levels [Konnova, 2024; Alekhina, 2024; Bešić, 2023], professional dispositions of teachers must be examined in their relation to the specific type of professional competencies—inclusion competencies. These competencies are instrumental in solving professional tasks unique to the inclusive education of children with disabilities [Chakravartya, 2022; Kuyini, 2023]. Inclusion competencies manifest themselves randomly, depending on the stage of the teacher’s professional career [Mavuso, 2022], their professional background [Montederamos, 2022], the level of school education, and the subject area [Xue, 2022; Žero, 2022]. Integral inclusion competencies include a teacher’s readiness to holistically approach the organization of inclusive education, ability to create individualized educational paths for students with disabilities, proficiency in providing them with individual and group support, and capacity to organize psychological and educational support tailored to the needs of students with disabilities. Additionally, these competencies encompass knowledge about the educational content and tools pertinent to working with students with disabilities [Kantor, 2021].

While there have been empirical studies on the professional dispositions and competencies of special education teachers in inclusive settings [Hong, 2009], no comparable research has been conducted on teachers working at general education schools. Although inclusion competencies of general education teachers have been assessed, namely, their professional beliefs about students with special educational needs [Vantieghem, 2023], a thorough investigation into their professional dispositions and competencies is still non-existent.

As a result, there is a significant gap in the theoretical and practical understanding of the relationship between professional dispositions of general education teachers and their competences in inclusive education. This paper aims to bridge this gap by providing evidence-based insights. The study is guided by the hypothesis that professional dispositions of general education teachers mediate the formation and development of their inclusion competencies.

Methodology and sample profile

The study involved 758 teachers from general education organizations across seven federal districts of Russia, including 234 primary school teachers, 411 secondary school teachers, and 113 teachers of supplementary education, aged 19 to 70 years (mean age: 43.94±12.46). The sample predominantly consisted of teachers with more than 20 years of professional experience (44.20%). Besides, it included young professionals with up to 5 years of experience (21.24%) and teachers with 5 to 20 years of experience (34.56%). Among the respondents, 407 educators (53.69%) reported having experience working in inclusive settings.

The sample was predominantly female (92.22%), reflecting the gender composition of the teaching workforce in Russia[Abakumova, 2008].

Our self-designed situational professional test [Kantor, 2022] was used to assess the level of inclusion competencies of teachers. According to the results of testing, the sample of teachers was divided into groups with low (224 people), medium (366 people) and high (168 people) level of inclusion competencies.

Professional dispositions of teachers were identified using another self-designed tool—a questionnaire with 5 scales that define dispositions in relation to oneself as a professional (‘self-awareness’), readiness to interact with colleagues (‘cooperation’), dispositions in relation to the subject taught (‘teaching’), dispositions in relation to students (‘students’) and dispositions in relation to inclusive education (‘inclusion’) [Kantor, 2023].

Statistical analysis of the obtained data was carried out using Statistica ver. 8 and Jamovi ver. 2.3.18. The data were processed using comparative, correlation, and correspondence analysis. The distribution testing of variables did not reveal normal distribution. Hence, the criteria and procedures of statistical analysis were based on nonparametric statistics.

Results and discussion

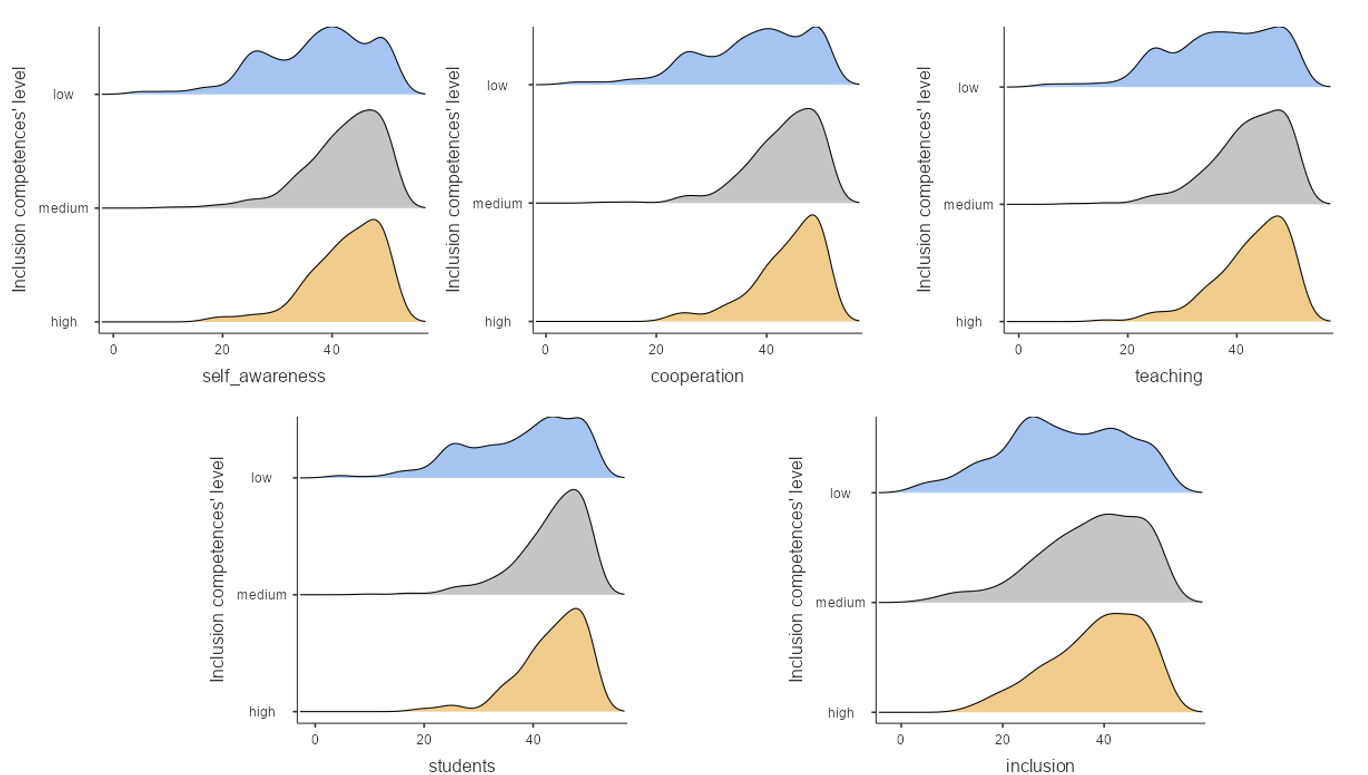

The analysis of the graphical representation of professional dispositions distribution across teacher groups with varying levels of inclusion competence (Fig. 1) revealed a significant trend. Teachers with high and medium levels of inclusion competence displayed a markedly skewed distribution towards higher disposition scores. Conversely, the group with low competence showed a more uniform distribution supported by statistical calculations of asymmetry and kurtosis indicators (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Distribution of professional disposition indicators in groups of teachers with different levels of inclusion competences

Furthermore, the low competence group exhibited the smallest distribution shifts from the center for all disposition indicators. Additionally, close to zero excess kurtosis in this group indicated the most uniform distribution. However, this group also displayed the highest standard deviation, highlighting considerable heterogeneity of assessed dispositions. The intensity of data scattering decreases across all the groups, while the heterogeneity of assessments for dispositions towards inclusive education increases. Furthermore, this indicator also showed the lowest median and mean values.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of professional disposition indicators in groups of teachers with different levels of inclusion competencies

|

Professional dispositions |

M (SD) |

Me |

As |

Ex |

||||||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

|

Self-Awareness |

37.3 (9.79) |

42.2 (7.06) |

42.5 (6.72) |

39 |

44 |

44 |

-0.68 |

-1.26 |

-1.19 |

0.16 |

2.03 |

1.58 |

|

Cooperation |

37.8 (9.98) |

43.1 (6.54) |

43.7 (6.36) |

39 |

45 |

45 |

-0.77 |

-1.42 |

-1.27 |

0.26 |

3.02 |

1.34 |

|

Teaching |

37.1 (9.88) |

42.2 (6.99) |

42.7 (6.73) |

38 |

43 |

44 |

-0.64 |

-1.17 |

-1.17 |

0.07 |

1.73 |

1.38 |

|

Students |

37.9 (10.0) |

43.3 (6.56) |

43.6 (6.18) |

40 |

45 |

45 |

-0.76 |

-1.53 |

-1.38 |

0.06 |

3.07 |

2.36 |

|

Inclusion |

32.1 (11.8) |

37.2 (10.2) |

38.4 (9.02) |

32 |

39 |

40 |

-0.24 |

-0.77 |

-0.63 |

-0.70 |

0.17 |

-0.38 |

|

Note: M—mean; SD— standard deviation; Me—median; As—asymmetry; Ex—excess; 1—low level; 2—medium level; 3—high level |

||||||||||||

The group of teachers with low inclusion competence exhibited the least pronounced professional dispositions. This finding aligns with the results of a Kruskal-Wallis H-test (see Table 2), which revealed statistically significant differences across all five professional disposition subscales (see Table 2).

Table 2. Kruskal-Wallis H-test values

|

Professional dispositions |

H |

df |

p |

|

Self-Awareness |

43.4 |

2 |

< .001 |

|

Cooperation |

51.1 |

2 |

< .001 |

|

Teaching |

47.1 |

2 |

< .001 |

|

Students |

48.4 |

2 |

< .001 |

|

Inclusion |

36.2 |

2 |

< .001 |

|

Note: H—criterion values; df—number of degrees of freedom; p—significance level |

|||

Further pairwise comparisons using the Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner test indicated no significant differences between the medium and high competence groups for any disposition indicator. However, both the medium and high competence groups displayed significantly higher disposition scores compared to the low competence group.

Correlation analysis using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient revealed a strong relationship between the indicators of inclusion competencies and professional dispositions (see Table 3).

Notably, the correlations strong in absolute value are only those between the cooperation-related dispositions and competencies in the organization of psychological and educational support for students with disabilities, their inclusive education and individualized educational paths. While the remaining correlations are statistically significant at 0.1%, they are still very weak in absolute values.

Table 3. Correlation matrix between the indicators of inclusion competences and professional dispositions

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

|

Inclusion competences |

|||||||||||

|

1. Knowledge |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2. Support |

.62* |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3. Process organization |

.72* |

.56* |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Accompaniment |

.70* |

.70* |

.77* |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Organization of individualized educational paths |

.55* |

.62* |

.38* |

.34* |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Total score |

.85* |

.82* |

.86* |

.88* |

.55* |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Professional dispositions |

|||||||||||

|

7. Self-Awareness |

.21* |

.23* |

.20* |

.19* |

.23* |

.25* |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

8. Cooperation |

.20* |

.25* |

.24* |

.22* |

.24* |

.27* |

.84* |

1 |

|

|

|

|

9. Teaching |

.18* |

.23* |

.23* |

.19* |

.21* |

.26* |

.87* |

.86* |

1 |

|

|

|

10. Students |

.18* |

.23* |

.21* |

.19* |

.23* |

.25* |

.85* |

.83* |

.85* |

1 |

|

|

11. Inclusion |

.18* |

.21* |

.20* |

.16* |

.22* |

.24* |

.71* |

.62* |

.69* |

.67* |

1 |

|

Note: * p < .001

|

|||||||||||

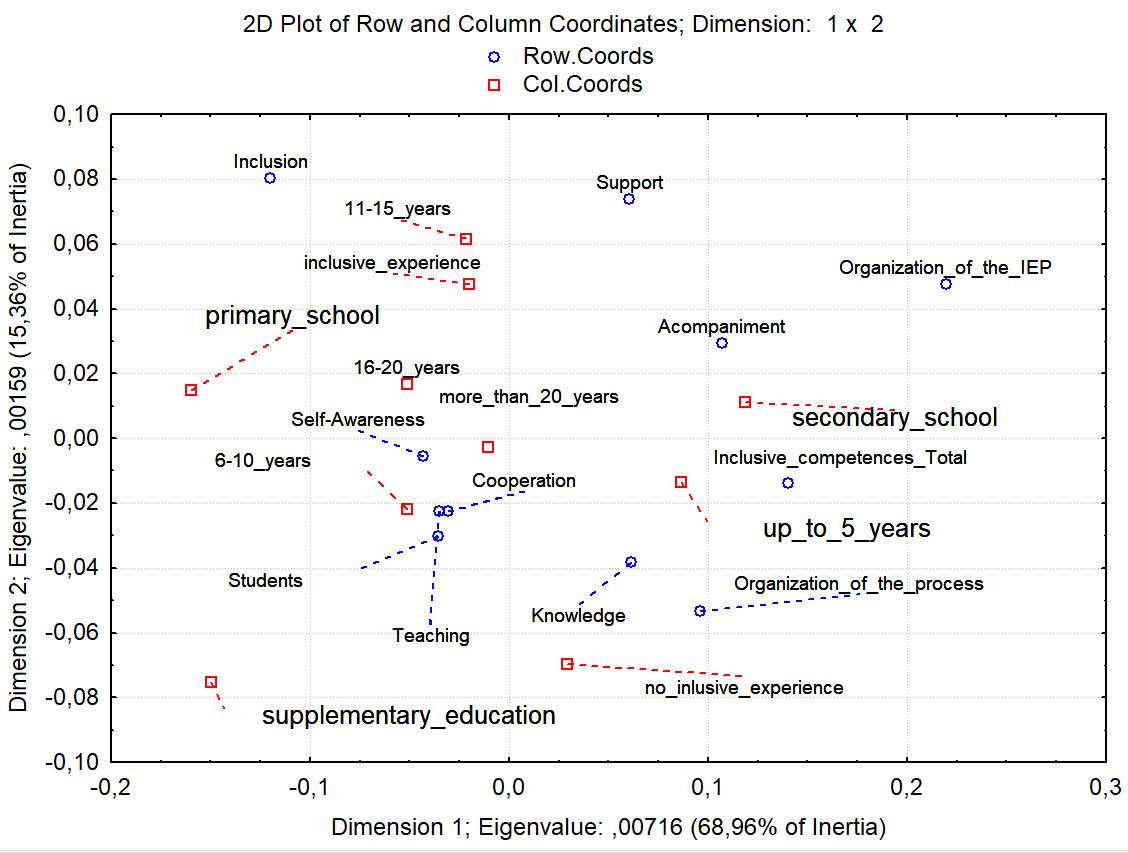

Correspondence analysis, employed in the final stage of the study, explored the co-occurrence of high level of inclusion competence and pronounced professional disposition across teachers with different social and professional characteristics (Fig. 2).

The analysis identified two significant dimensions explaining a cumulative 84.32% of the total inertia, which indicates a highly informative model. Additionally, the chi-square test confirmed satisfactory relationships within the model (χ² = 115.249, df = 90, p = .0379).

Fig. 2. Correspondence map between inclusion competences, professional dispositions and social and professional characteristics of teachers

The first dimension (horizontal axis), accounting for 68.96% of the total inertia, positioned inclusion competencies at one extreme and professional dispositions at the other. Interestingly, social and professional characteristics gravitated more towards professional dispositions, suggesting a stronger connection with the practical aspects of teaching. Notably, inclusion competencies were more pronounced among secondary school teachers. Conversely, primary and supplementary education teachers displayed stronger professional dispositions but lower levels of inclusion competence.

The second dimension (vertical axis), explaining 15.36% of the inertia, contrasted ‘direct interaction with students with disabilities’ at the upper pole with a focus on the ‘formal basis for inclusion’ (knowledge of regulations, program development) at the lower pole. This essentially reveals a dichotomy between ‘student-centered’ and ‘process-centered’ approaches to inclusion. Furthermore, the ‘student-centered’ orientation aligned with the professional disposition of valuing inclusion. This was more evident in teachers with prior experience in inclusive settings. Conversely, teachers lacking such experience, particularly those in supplementary education, displayed a stronger emphasis on developing competencies related to supporting inclusive education. Notably, teaching experience exhibited a weaker association with these dimensions. While teachers with extensive experience (>15 years) showed a link with self-centered professional dispositions, those with 6–10 years of experience focused more on the subject they teach, students, and cooperation with other professionals. Young professionals, on the other hand, demonstrated higher levels of both inclusion competencies and relevant knowledge.

Our findings suggest that already at their average level, inclusion competences facilitate a qualitative shift in professional dispositions. This suggests that professional dispositions may be a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for developing inclusion competence. Indeed, other factors of a teacher’s professional development—organizational, methodological, and psychological— also play a crucial role [Makhambetova, 2023]. However, fostering a teacher’s role as an inclusion educator cannot be achieved without cultivating their professional dispositions. These dispositions shape teachers’ understanding of their professional identity and the nature of inclusive education.

Conclusion

This study delves into the relationship between professional dispositions and inclusion competencies of general education teachers, revealing a multifaceted and nuanced interplay. The findings challenge the notion of professional dispositions as sole determinants of inclusion competence development. Instead, they emerge as the foundation and core semantic components that shape a teacher’s professional orientation and goal setting, ultimately serving as crucial drivers for competence development.

A key insight is the identified connection between the ‘inclusion component’ of professional dispositions and a teacher’s inclusion competence. This manifests primarily in a focus on the student with disabilities. However, the organization of inclusive education per se to facilitate a student’s successful integration within the school environment was given less priority.

The study found an asymmetry in the relationship between the inclusion component and other aspects of professional dispositions. The findings suggest that teachers do not associate personal value of inclusion with other fundamental elements of their job. Further empirical exploration to verify this assumption presents a promising avenue for future research.

The significance of this study extends beyond the immediate findings. It contributes theoretically by deepening our understanding of the mechanisms and regularities that govern professional and personal development of inclusive education teachers. From a practical standpoint, the results illuminate the need for a differentiated approach in supporting this development. By acknowledging the multifaceted nature of the relationship between dispositions and competencies, targeted interventions can be designed to address specific areas where teachers require the most support.

[Abakumova, 2008] According to the data of the Federal Statistical Observation No. GE-1 ‘Information about an educational organization of primary, basic and secondary general education’ at the beginning of 2023–24 school year. URL: https://docs.edu.gov.ru/document/dd4cf021660425786495d744405367f0/