Introduction

The level of development of children’s play remains low for a long time [Abdulaeva, 2020; Smirnova, 2013]. An insufficient amount of play in kindergartens can be attributed to numerous factors, including changes in social situation of development, disappearance of mixed-age children’s communities, substitution of play by structured adult-led play and play forms, too many school-type activities in a preschooler’s timetable or a lack of free time for play, etc. [Klyuchevye problemy realizatsii, 2017; Kravtsov, 2019; Smirnova, 2013]. Though most teachers recognize the meaning and value of play for early childhood development, true play is very rare in kindergartens.

According to Vygotsky, “… If there is no the appropriate ideal form in the environment, the appropriate child’s activity, feature and quality won’t develop” [Vygotsky, 2001, p.86]. For play development children must experience ideal form of play, not its distorted version. According to the cultural-historical approach, we consider imaginary situation as a main criterion of play and double-subjectivity as its main feature. Double-subjectivity is the ability to simultaneously hold positions “in” and “out of play”, to play and control the course of the play at the same time [Kravtsov, 2017]. Researchers emphasize the increasing role of an adult in play support [Singer, 2019; Smirnova, 2017; Preschool Teachers’ Conceptualizations, 2018]. Play support can be indirect (a teacher does not participate in children-led play) or with adult’s participation in joint play. The more effective adult’s position for play support is partner position. Partner position means that the adult respects children’s own play initiatives and suggests his/her ideas according to the flow and logic of children’s play [Singer, 2019; Hakkarainen, 2013]. Adult’s didactic position (exploiting play for teaching, directive style of interaction and capture of all the initiative in play) destroys children’s spontaneous play [Smirnova, 2017].

Studies from different countries show that preschool teachers more often prefer “outsider position” in play support [Devi, 2018; Hakkarainen, 2013]. Russian teachers more often take an “outsider” or didactic position, they destroy play by inappropriate questions, infusion of additional educational tasks in play, or desire to make play more complete and spectacular [Korotkova, 2012; Smirnova, 2017; Trifonova, 2017].

Smirnova [Smirnova, 2017] and Fleer [Fleer, 2021] consider preschool teachers’ professional development as a transition from “outsider” or didactic position to a partner position in joint play with children. The challenge for researchers is to answer the question of what can facilitate this transition and make adult-child partnership in joint play more sustainable.

Pedagogical Observation of Spontaneous Play

Observation is an important part of play support. It helps teachers notice the needs of each child, create togetherness, be responsive and flexible in choosing the strategy of play support [Singer, 2019; Smirnova, 2017; Hakkarainen, 2013]. Observation can help a teacher to participate in joint play as a partner. However, some teachers prefer only to observe play staying in the “outsider” position; reducing their role only to observation providing materials [Devi, 2018]. Observation can help teachers participate in play or prevent from playing together with children, depending on how teachers practice observation, what aspects of play they focus on and how they use observation evidence. Observing children engaged in play is complicated, as many aspects of play are not obvious, and there is always a risk of misinterpretation or labeling children. Vygotsky argued: “Play is not just a recollection of child’s experience, but a creative transformation of the experienced impressions, combining them and creating with them new reality, responding to child’s own needs” [Vygotsky, 1991, p.87]. For effective play support and genuine partnership in joint play, teachers should understand what constitutes the basis of spontaneous play (“perezhivanie” and creative transformation of meaningful experience, not just reproduction of ready scenarios) and observe it regularly, use their observations to be flexible and responsive to child’s play, decide whether they need to join play or not.

The way teachers observe children play may depend on their understanding of play and its role in the child’s development [Differences in practitioners’, 2011]. Therefore, it is necessary to study teachers’ perceptions and viewpoints on free play and its observation in kindergartens.

Teachers’ Views on Children’s Play

Recent studies indicate that Russian preschool teachers often expect play to be coherent, spectacular and scenario-based, which is contradictory to the very essence of spontaneous play [Korotkova, 2012; Trifonova, 2017]. But these studies don’t analyze how teachers’ views are interrelated with real practice of play support in classrooms. Several small-sample qualitative studies include observations in classrooms (without using quality assessment rating scales) and point to a connection between teachers’ views and their real strategy of play support [Pyle, 2015; Ranz-Smith, 2007]. Rentzou et al. [Preschool Teachers’ Conceptualizations, 2018] showed that teacher’s views on play influence real practice, however, the study is based on a survey, which is not a sufficiently reliable method for assessing the quality of play support.

Studies also show that teachers’ views and beliefs regarding spontaneous play (including their understanding of play and its learning and developmental potential, the requirements of the educational program) are related to their preferred position in play support [Devi, 2018; Pursi, 2018]. Understanding spontaneous play as an adult-free activity may prompt teachers to stay outside of children’s play, while their understanding of play as a form of teaching and learning may provoke excessive infusion of didactic tasks to play. However, this assumption needs further verification.

There is deficit of research on the relationships between teachers’ views on play and the quality of play support in kindergartens, the analysis of differences in play support provided by teachers with diverse views on play.

The purpose of this research is to study preschool teachers’ views on children’s play and observation as well as to analyze the differences in views on play held by teachers using different strategies of play support in their classrooms.

Research hypothesis:

Teachers with different views on play use different strategies of play support. The more teachers consider play as valuable for itself, the more often they observe play and the higher the level of play support in their classrooms.

Teachers working in different educational programs vary in their attitudes toward play observation. If an educational program puts an emphasis on supporting play, teachers will observe children playing more often and use their observations to plan play support.

Methods

The study was conducted in the 2021—2022 academic year in two stages: 1) study of teachers’ views on spontaneous play and pedagogical observation (online-survey); 2) quality assessment (structured expert observation) of play support in kindergartens in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kostroma and Almetyevsk.

All participants of the study gave voluntary consent to participate in the survey and the assessment procedure and at any time could refuse to proceed. All the data has been anonymized.

Studying Teachers’ Views on Play

To study preschool teachers’ views on play and observation, we conducted an online survey based on the research of Bulgarelli and Stancheva-Popkostadinova [Besio, 2018]. The survey contained two set of questions. The first sed included general questions on the participants’ place of work, teaching experience, current position and educational program, the age of children they work with. The second block featured questions concerning the teachers’ understanding of spontaneous play and their attitudes to observing it.

All the respondents represented Moscow and three other Russian cities and answered the questions via an online form.

Assessing the Quality of Play Support

To assess the quality of play support we used the ‘Play Support Rating Scale’ (PSRS) [Shkala “Podderzhka detskoi, 2022] designed on the basis of: 1) the cultural— historical approach of understanding play and the conditions necessary for play development; 2) the principles of constructing quality rating scales of ERS [Associations between structural, 2015]. The PSRS is based on the idea of complex play support that requires adult’s participation in play as a partner, support of peer-interaction, organization of environment, empowerment of play during the whole day in the kindergarten. PSRS includes 7 items: 1) space and equipment for play, 2) time for play, 3) materials for play, 4) indirect play support; 5) adult’s participation in play, 6) peer-interaction in play, 7) mixed-age interaction and play. Each item includes the set of indicators (95 in total) grouped into 4 quality levels: inadequate (1—2 scores), minimal (3—4 scores), good (5—6 scores), excellent (7 scores). The PSRS allows to analyze both the overall quality of play support and the quality of conditions for play described by each item. PSRS has been validated and has a sufficient level of reliability and validity [Razrabotka i aprobatsiya, 2020].

To assess the quality of play support according to PSRS, experts conducted 3-hours non-participant observation in the morning in each classroom. Before participating in the study, all the experts completed a training program on how to use PSRS (inter-rater reliability is more than 80%).

Sample

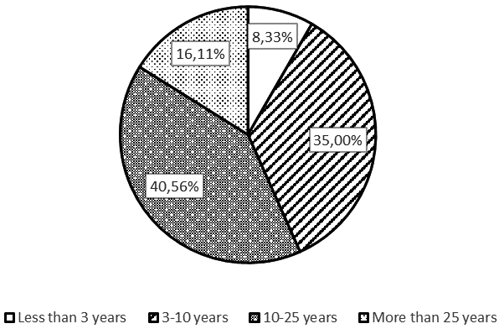

On the first stage of the study the sample consisted of 180 participants: 68.3% of the sample were certified preschool teachers, 17.2% held a position of a senior teacher or methodologist for preschool, 14.4% — other educational professionals. Moscow residents made up 37.2% of the sample. The overwhelming majority of the respondents (87.8%) worked in the public sector, 11.1% were employed by private kindergartens and daycare centers offering full-day or half-day programs, 1.1% of the respondents worked in mixed-aged play-based classrooms and didn’t follow a specific educational program. The working experience of the survey participants is shown in Figure 1.

The survey participants worked with children of early preschool age (2—4 years, 20%), preschool age (4—6 years, 32.8%), early age (1.5—2 years, 5%) and mixed-age classrooms (42.2%).

The most popular educational programs for preschools are designed on the basis of recommendations of the Ministry of Education of the Russian Federation [Reestr primernykh programm] and are available on the online platform ‘The Navigator for Educational Programs for Early Childhood Education’ [Navigator obrazovatel’nykh programm]. Our sample includes the following programs for preschool education: ‘Ot rozhdeniya do shkoly’ [From birth to school] (51,1%), ‘Vdokhnoveniye’ [Inspiration] (11,7%), ‘Detstvo’ [Childhood] (8,3%), ‘OtkrytiYa’ [Discoveries] (5,6%), ‘PROdetey’ [ABOUTchildren] (6,1%) and ‘Detskiy sad po sisteme Montessori’ [Montessori] (5%). A much lower number of teachers relied on unique author’s programs, such as ‘Istoki’ [Springs], ‘Razvitiye’ [Development], ‘Raduga’ [Rainbow] and ‘Mozaika’ [Mosaic] (1—2% or less). The data reflect the current situation with educational programs used in Russian kindergartens.

The second stage of the study included a series of observations in 25 preschool classrooms where 27 teachers, who took the survey on the first stage of our study, work. Our sample includes classrooms with different quality of play support, with an average score on PSRS of 3.63 and a standard deviation of 1.12. All in all, play support in the groups from our sample varied from inadequate (min = 1.57) to good (max = 6.00).

Results

The teachers vary in their understanding of play: 41.7% of the sample see it as a valuable for itself and as a resource for child development, 52.8% consider it as a context for teaching, assessment of academic progress, behavior correction, or personality development, while 5.6% believe play is leisure or recess-time.

Fig.1. Distribution of the respondents by work experience

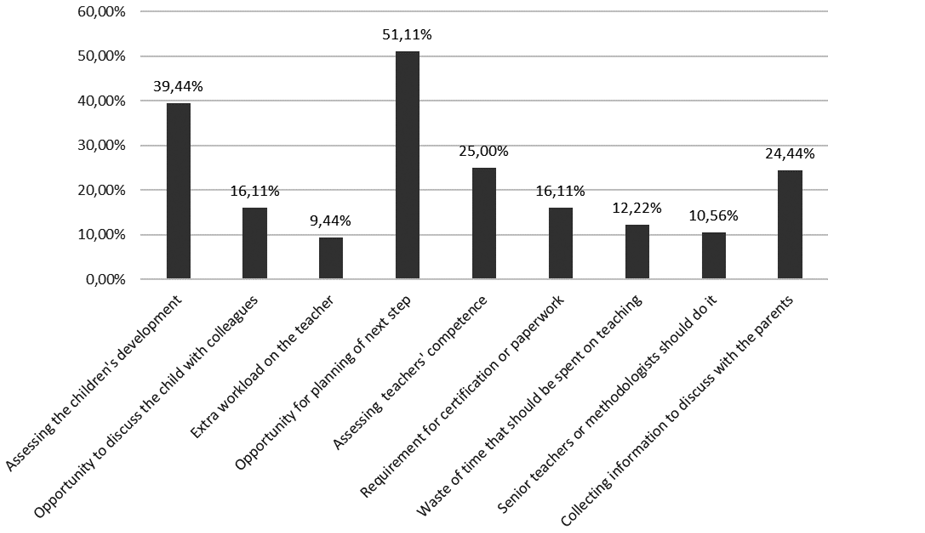

Fig. 2. The distribution of the first priority answers to the question ‘What is pedagogical observation in your daily practice?’

When asked ‘How do you evaluate the level of play development?’, most of the respondents said they observe children engaged in play. 1.1% of the respondents said they conduct observation in laboratory settings, 52.2% regularly observe children in everyday settings, 41.7% observe play from time to time to notice remarkable details, 2.8% said they don’t assess children’s playing skills at all. Some of the given answers on these two questions contradict with each other, probably due to a distorted observation focus: watching preschoolers playing, teachers pay little attention to the play itself (they don’t evaluate play development) yet evaluate children’s abilities in other areas, such as communicative and cognitive skills, speech development and other learning outcomes. Only 37.3% of kindergartens in the sample made it a rule on the organizational level for their teachers to observe play.

The teachers’ attitudes to observation are polarized, with some recognizing its necessity and others describing it as useless and burdensome. About half of the teachers said they use information from observations to plan educational process (51.1%) and less than a half (39.4%) said observations help them assess a child’s level of development. It is puzzling that a significant number of the respondents (39.1%) believe that observation of child’s play is a legitimate procedure to evaluate teachers (for certification or quality assessment purposes), which is directly prohibited by the Federal Law 273-FZ ‘On Education in the Russian Federation’ and the Federal State Educational Standard for Preschool Education [Federal’nyi gosudarstvennyi obrazovatel’nyi]. The teachers’ views on pedagogical observation are presented in Figure 2.

To test the hypothesis of whether teachers’ professional understanding of play is related to their attitude toward pedagogical observation, we conducted a statistical analysis of the collected data assigning scores to each answer choice and summing scores as a respondent’s profile (total score).

First, we divided the respondents into two clusters according to their views on play and used the Welsh’s t-test and the Mann—Whitney U-test to compare them. The normality of the distribution was confirmed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. No significant differences were found (at the significance level of 0.05) for any value. An average profile of the teachers praising play as valuable for itself is 4.51 out of 7; an average profile of the respondents with opposing views is 4.04; p-value = 0.19 according to the Welsh’s t-test; p-value = 0.23 according to the Mann—Whitney U-test.

We applied the same statistical method to test the hypothesis about differences in teachers’ views on play from classrooms with different quality of play support as measured on the PSRS. Total PSRS score and scores for items about indirect play support, adult participation in play and peer interaction in play were used for statistical analysis. No significant differences were found. For the PSRS total scores, an average profile was 3.76 for the ‘play is valuable for itself’ cluster and 3.43 for the contrasting cluster, with p-value of 0.56 (t-test) and 0.51 (U-test). Average profiles for the indirect play support item were 3.82 and 3.70 respectively, with t-test p-value of 0.86 and U-test p-value of 0.88. Average profiles for the adult participation item were 2.71 and 2.20, with p-value = 0.50 and 0.26, average profiles for the peer interaction in play item were 4.41 and 3.60, with p-value = 0.20 and 0.17.

To form clusters according to educational programs, we analyzed answers of the teachers who worked with the educational programs implemented by at least 5% of the whole sample (6 different programs in total). We found no significant differences in profile scores of the respondents working with certain programs regardless of their pairing, with the Welsh’s t-test p-value ranging from 0.08 to 0.96 and the Mann—Whitney U-test p-value = 0.053 to 0.94.

Discussion

Most of the teachers involved in our study consider play as a form of teaching or context for other activities, not as something valuable by itself, which is consistent with the data obtained in foreign [Besio, 2018] and Russian [Trifonova, 2017] studies. We found no significant differences in views on play of the preschool teachers with different quality of play support. A relatively large number of teachers’ answers about the value of play yet score low in play support quality, it may be related to teachers knowing of the requirements of the Federal State Educational Standard for Preschool Education [Federal’nyi gosudarstvennyi obrazovatel’nyi] without deepening their knowledge of children’s play. Speaking of the value of play, teachers may consider it as a freedom from any adult intervention or, conversely, point to the advantages of utilizing play as a teaching tool.

The teachers, regardless of their views on play, rarely joined it as partners, which supports the results obtained by Devi et al. [Devi, 2018]. The opposite views on play and its value manifest itself in an apparently similar support strategy with a teacher taking an “outsider” position [Vygotsky, 1991]. However, unsignificant differences in play support strategies preferred by teachers holding different views on play may be attributed to the research method (a survey) or the teachers’ overall lack of awareness and reflection on their professional decisions in relation to children’s play. The study of interrelation between teachers’ views on conditions for play development, their role in play support and possibility to be a partner in joint play may be the issue for future research.

The majority of teachers report that they regularly observe children engaged in play and use their observations to plan appropriate play support. However, the quality of play support in most of the observed classrooms was minimal. Some teachers said they consider play observation as an assessment of their skills needed to obtain another certification, which contradicts the existing legislation and turns observation into a formal procedure. Observation is only effective as a part of complex play support that helps a teacher interact with children based on their interests, ideas and needs [Hakkarainen, 2013; Pursi, 2018].

Aspects that teachers tend to focus on during observation are often secondary to spontaneous play or even misleading [Korotkova, 2012; Kravtsov, 2017], which can make observation evidence irrelevant for planning play support. Further research is needed on how exactly teachers observe play and use their observations to plan play support, how regular observation is related to the quality of play support. It also might be necessary to provide in-service training for teachers focused on reflection on their views on play and development of competence for play observation [Differences in practitioners’, 2011].

Play support strategies may be influenced by quality of kindergarten’s norms or organizational culture [Associations between structural, 2015]. Our research has shown that observation in most cases is solely a teacher’s initiative, not a requirement put forward by an educational organization. This may be explained by the fact that pedagogical observation isn’t considered a part of teacher’s everyday practice or an important step in planning play support. If a kindergarten doesn’t expect teachers to observe children engaged in play, a teacher who does so anyway may receive criticism from colleagues and administrators. Therefore, when studying teachers’ views on spontaneous play, their role in it and its relation to play support strategies and overall play support quality, it is important to take into account the culture of the entire organization.

The absence of significant differences in views on play of the teachers implementing different educational programs may be explained by insufficient methodological assistance for teachers in program acquisition. With no proper guidance, they tend to see a given program as a formality, not as a guide for professional development. To test this assumption, it is necessary to conduct research on a wider sample.

Conclusion

Preschool teachers vary in their views on play and attitudes to its observation, yet there is no significant difference in their strategies of play support, different educational programs also aren’t related to differences in strategies of play support. There is no significant difference in views on play of the teachers from the classrooms with different quality of play support. Further research is needed to study teachers’ views on the conditions of play development and their role in play support in relation to the actual practice of play support; to study how teachers understand spontaneous play and their role in its support implementing different educational programs; to identify aspects of preschool organizational culture that determine conditions for play development in kindergartens.

The obtained results can be used for elaboration of professional development programs for preschool teachers aimed at reflection and deepening their understanding of children’s play and mastering pedagogical observation and play support planning.