Introduction

The new, and very heuristic, term "transvitality" was first introduced into the thesaurus of modern personality psychology in the work of L.S. Akopyan [Akopyan, 2015, p. 12]. Akopyan's articles discuss "transvital meanings", which embody the aspiration of people (especially elderly people) for post-life continuation, the desire to leave behind a memory in deeds, ideas, in created material and non-material values, in descendants. "Transvital meanings", in our opinion, embody what we understand as the need for personalization, i.e. the human desire to find its ideal representation and continuation in other people, and this desire is interpreted by us as a manifestation of the fundamental human need for immortality [Petrovsky, 1984; Petrovsky, 1981].

It should be noted, however, that the new term potentiates something more than "transvital meanings". The meaning of this term includes, in our opinion, a number of interrelated phenomena, each of which deserves special attention. We are talking about manifold forms of existence of the Self ("I exist"), which do not coincide with the manifestations of an individual's life activity in the system of processes of reproduction of his psychophysical integrity.

The aim of the research is to substantiate the possibility of the existence of the transvital Self as a special phenomenon of human existence on the border and beyond ("on the other side") of the present forms of his/her life activity.

Research methods. The research principles of general personology [Petrovsky, 2003], [Petrovsky, 2020] are implemented in the work: the analysis of cultural texts, evidence of consciousness and biographical data of people, the author's experimental methods ("virtual agency", "reflected agency", multi-agent dialogues in the counseling process).

The Idea of Transvitality

This paper deals with one of the central problems of "peak psychology" (L.S. Vygotsky) - the problem of the Self. Among many other aspects of the problem is the phenomenon of the presence of the Self in the world "beyond" or "on the other side" of its present existence as an individual, beyond the task of reproducing itself as a psychophysical integrity. The term transvitality, which is quite new for psychology, is used. In its original meaning, it is associated with the answer to the fundamental question of being: "What will be left of me in the world after I die?" [Akopyan, 2015][Aquinas]. This is an important, but, as it seems, not the only meaning of the term.

Three meanings, equally important and critically irreplaceable in the understanding of the "Self" as a transvital being, can be singled out.

The Supra-Vital Self

Proceeding from the understanding of the individual as a psychophysical whole [Petrovsky] and vitality (life per se) as a set of processes of reproduction of the individual, we say that the value of human being is obviously higher than the ability of a person to adjust to the world, to adapt, realizing natural drives and assigned social requirements (even if refracted through one's own experience) [Petrovsky, a]. But the fact or, perhaps, the "drama" of human existence is also that the vital, life aspirations of man often contradict themselves, as if "turning" against themselves: "To live is to die" (vitality turns into lethality); "There is a disease from which everyone dies" (this is life); "You went into a room and found yourself in another"; they were looking for Ivan the Terrible's library, but unearthed something that has nothing to do with the "spiritual". A person sets a goal and eventually misses, sometimes acting in his own favor (for example, he finds a treasure), sometimes to his own detriment; a "life impulse" (pathetics of life), dramatically "breaks" with life, not turning into a "breakthrough"[Akopyan, 2015]; this happens in cognition, love, business, invention. Resorting to a metaphor: a "Black Swan" [Taleb, 2012] lives inside people and "pecks" them in the brain, in the heart, in the liver; a person is a "generator of uncertainty" (A.G. Asmolov [Akopyan, 2015]), loses control over the consequences of what he does and how he lives; he loses his agency.

Transvitalism, in its first meaning, is a way of affirming human agency as such - authentic human agency[Aristotle. Sochineniya v, 1975], i.e. the ability to control the results of one's choices even when it is impossible to guarantee the achievement of what one wants. Human agency in this case is defined by the fact that the absence of guarantees encourages a person to set a goal that may not be achieved. In this and only in this case a person, paradoxically, is able to control the outcomes of his actions (anticipating success or failure in advance). Intentional choice of the undecided opposes vitality as a tendency to the guaranteed reproduction of what is or was. This is the essence of active maladaptivity (Petrovsky [Petrovsky, 1992; Petrovsky, a]); here the challenge provokes choice: it lures by unpredictability, unpredictability of expected outcomes of action.

We note the signs of transvitalty in cognition, creativity, and communication with relatives and those far away. We discover a class of phenomena of authentic human agency: refusal of hints when solving difficult problems [Kornilova, 1980; Petrovsky, 1992]; the "presumption of the existence of a solution" when we do not know whether a solution exists at all [Petrovsky, 1992]; posing problems in the place of a solved problem [34; 5; [Maksimova, 2020]; performing "inversive actions" [Kudryavtsev, 1997]; "non-reactive" creation of task complexity [Petrovskiy, 2019].

Biographical examples

The father of Hungarian mathematician J. Bolyai, himself a mathematician, exhorted his son not to take up the proving of Euclid's postulate V (there were cases of madness on this ground), but the son disobeyed his father's advice and, in parallel with Lobachevsky, immortalized himself by creating non-Euclidean geometry.

A similar example explaining the idea of transvitality in the aspect of non-adaptability. Nikolai Lobachevsky, unlike Gauss, risked publishing his geometry that contradicted all canons (however, cautiously called "imaginary") and earned a lot of censure from others. Obviously, immortality in the memory of generations and immortality in the eyes of contemporaries are different things. Thus, at Lobachevsky's funeral, high figures of mathematics and enlightenment were not supposed to talk about the scientist's whimsy, with his "imaginary geometry", while it was quite proper to talk about the first rector of Kazan University, N.N. Lobachevsky. However, it was censored. In the sincere and sad eulogy of Professor N.N. Bulich nothing was said about Lobachevsky's "imaginary geometry", but the speaker also deserved censure; he was accused of atheism and political unreliability on the denunciation of the then rector of the Theological Academy [on this speech see: 11].

What do we know about the youth of the "maladaptive" Lobachevsky? "Studying at the state’s expense, he lived practically in barracks conditions: he could not freely leave the gymnasium and university and see even his mother, he was obliged to follow a strict schedule and discipline. Nevertheless, the young man grew up freedom-loving and stubborn. He loved, as they say, to dabble. His name was entered 33 times in a special book of violations - the conduit. Lobachevsky rode a cow; jumped over the obese Professor Nikolsky on a bet; went to masquerades, despite the ban, launched a rocket in the university yard. For the last offense, he served three days in the punishment cell - then it was an educational measure. For participation in masquerades Lobachevsky was almost expelled and sent into the soldiers ... In adulthood Lobachevsky was not the only mathematician who approached the discovery of non-Euclidean geometry. But it was Lobachevsky who was the first to publish a work that challenged all previously held notions in mathematics. He was the only one who actively continued to work on non-Euclidean geometry and to publish his works on it, despite the criticism <...> "Contemporaries considered Lobachevsky a freak scientist. He never saw scientific recognition during his lifetime, and died in poverty." [Vdovenko]. The corresponding "criticism" (I cannot help putting quotation marks) of Lobachevsky's works was crushing (I will allow myself a more accurate emotional word - disgusting)[Asmolov, 2017].

There are three possible outcomes when a person - maladaptively - accepts the challenge

The first option is the story of the protagonist of Crime and Punishment, Rodion Raskolnikov, and similar stories. Raskolnikov... He, as we know, "dared to want to dare", he wanted to prove that he was "not a louse" and "not a trembling creature". For this purpose, he acted thoughtfully: he took and killed the old woman. He showed the "freedom" of his own will. The finale: penal servitude and repentance, and then consolation in the person of Sonechka. It turns out: Crime - Punishment - Redemption - Consolation? Agency is tested and seems to be proven. But what is the price and value of this test?[Bogoyavlenskaya, 1971]

The second variant of the outcome - the flight of V. Chkalov under the Trinity Bridge in Leningrad, with the subsequent expulsion of the pilot from the Air Force for a hooligan act and admiration in the eyes of the people.

The third option is "acting at my own risk and winning". An example is the phenomenon of flutter known to pilots, aircraft bumpiness when crossing the supersonic barrier (identified as a special psychological phenomenon by I.M. Shmelev and described by us as a variant of mastering behavior (not to be confused with "coping" behavior, coping) [Tolstoy, 1956; Ergasheva, 2021].

Non-adaptive personality tendencies have been experimentally investigated by the author since the early 1970s. Many of these phenomena are described in the book "Man Over the Situation" [Petrovsky, a] and others. Evolutionary problems were practically not touched upon in our books[Brudny, 2003]. In contrast to the author of these words, A.G. Asmolov, the founder of the School of Anthropology of the Future, and his colleagues launched a powerful movement to study preadaptivity as an evolutionary phenomenon, the conditions of personogenesis [Asmolov, 2017]. The special significance of the idea of "pre-adaptivity" in the context of transvitality is emphasized, in our opinion, by the fact that pre-adaptivity is "pregnant" with three variants of its "resolution" in the evolutionary process (which once again confirms the idea of diversity, multivariate forms of development defended by Asmolov). The first possibility is adaptability proper (i.e. adaptability at a new turn, which seems to be directly indicated by the word "pre-adaptability"). The second possibility is maladaptivity (destruction). The third possibility is supra-adaptivity.

The last of these is transvital (does not produce a future spiral of adaptability), does not produce a role model, and forms a fundamentally unique being. Supra-adaptivity is self-valuable (it exists "not why"). Let us compare it with a natural phenomenon - the wind: it "blows", but not for the sake of something and not for some reason; it "blows" for some reason and somewhere, which does not prevent "it" from turning the blades of a windmill (it is an acting, not a purposeful reason, if we follow Aristotle [Aristotle. Sochineniya v, 1975]).

Supra-adaptivity is not a norm, but, perhaps, it is a new value: it does not serve the interests of adaptation, does not "adapt" to anything; at the same time, it "itself" does not prescribe anything to anyone (does not require others to "adapt" to it).

Note that a person, going beyond the necessary and proper, at the expense of differences visible to other people, "enters" other worlds - personalizes himself, acquiring a second being, a being beyond himself, his ideal being. E.V. Ilyenkov defined the ideal as "the being of a thing outside of a thing"; in this case we are talking about the being of an individual outside of the individual himself, about his existence in other people, - about other-being [10, pp. 219-227]. We also use here the term "personalization" to emphasize the acquisition by an individual of the quality of "being a person".

The Meta-Vital Self

In front of the reader is one of the so-called "magic pictures" (Fig. 1). What do we see? If the reader has enough time and effort, the flat picture will turn into a volumetric one, and the observer will be in for a surprise.

Figure 1. Let's look through this picture into the distance and be rewarded by what we see (if we see it)

The fascinating metamorphosis has an additional meaning for us. Psychologically, in addition to the cognitive paradox, no less interesting will be the fact that the person who first saw the hidden object will persuade the other person, who is also contemplating this picture, to see what he or she has seen; will make more and more persistent attempts to "share" his or her experience: "Look, look, look, there, there!..". And this does not seem to be altruism, but a search for confirmation that he is not deluded in himself in believing that he is seeing. Otherwise, his Self for him is an illusion, a phantom, something akin to a pseudo-hallucination (as understood by V. Kandinsky). Indeed, phenomenologically, something exists objectively; this means that "not only I see it, but someone else whom I see (or can see) sees the same thing"; and if what I observe is absent for the other, then I am absent for that person as an observer: "I am absent at that moment for him". In other words, to recognize oneself as existing for others is to make sure that the world (the image of the world) you see exists for another. Hence the insistence that others see what is revealed to me.

But how, in what form, do we experience the presence of others in us, their "subjective reflection"?

In Leo Tolstoy's treatise "On Life" we read: "My brother has died, but the power of life that was in my brother, not only has not diminished, but has not even remained the same, has increased, and is stronger than before, influences me. ... His attitude to life allows me to clarify my attitude to life." [Tarabrina, 1984, с. 412]. But it is not just the image of my brother in my head - it is the "work" that the image produces. The reflected agency (subjectivity) of the other means the subjectivity of the reflection itself - in the form of the influence that the image of the other has on us. The person leaves, and we take into ourselves the vitality of the other. The energy of his life.

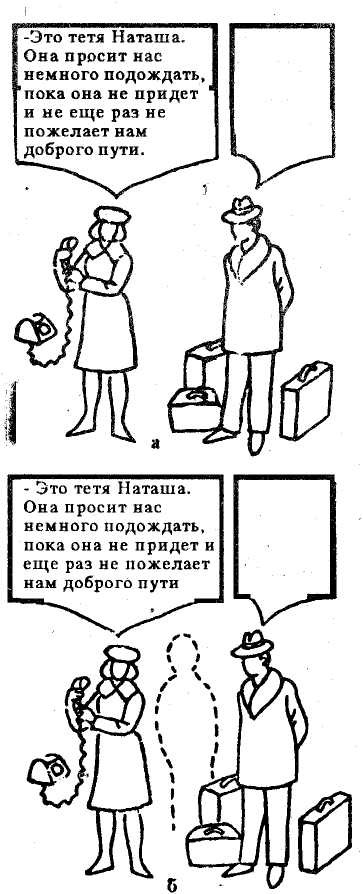

The author studied the phenomena of influence empirically, in co-authorship with I.P. Gurenkova; the author used a modification of the Rosenzweig frustration reactions test [see: 37] (Fig. 2):

Fig. 2. Rosenzweig test: a) conventional, b) modified [26, 1985].

The "induced" image significantly changes the nature of agents' reactions, for example, extrapunitiveness increases (while reactions to these pictures are rather stable). Such changes affect the originality of associations to stimuli, risk-taking tendencies, self-esteem, self-perception in the mirror, and even perceptual illusions.

The critical question is: what if my existence, due to divergent pictures of reality, is questioned by someone else? What is to be done in a situation of cognitive dissonance, which turns into a feeling of "abolition" of oneself under the gaze of another.

There is no general solution, but there are only some clues to avoid "the trauma of mutual misunderstanding" [Petrovsky, b].

The Cross-Vital Self

Fig. 3 shows a man pointing his finger at the viewer (in the original version, a Red Army soldier from a Civil War poster). Who is the man from the poster looking and pointing his finger at? By changing the observation position, we get a different answer.

Fig. 3. "Who is the man looking at?"

It was investigated how children in kindergarten experience such a gaze (unpublished master's thesis [Frumkin])[Vdovenko].

Two children sitting on two chairs, some distance apart, were shown a picture and asked "who the man in the portrait is looking at". Each child naturally answered: "At me!" Then the children, at the direction of the experimenter, moved, changing places. At the same time, the "man" "saw off" each child with a glance, "aiming" with his finger. The children changed places and the question was repeated. Each of them stood their ground: "At me!" They were surprised, argued, insisted.

Sometimes, however, bewilderment gave way to discovery: "The man is looking at us." The idea of "WE" appeared, uniting those who saw different things. Five-year-old children "discovered" M. Heidegger. Heidegger's phenomenon of co-existence (co-presence), "the relation of presence to another presence... The peculiarity of co-presence consists, among other things, in the fact that the presence itself, for the most part, does not separate itself from those with whom it is co-present, they make up a joint world" [Faradzhev, 2021].

The word "co-existence" in Old Russian corresponded to some extent to the word "self-friend". It meant: "on a pair", "together (with someone)", "tete-a-tete", but also "apart", "secluded", "separate". In the first case, it is not only a statement of the fact that "I am not alone", but also an experience of community with another person, "me plus another". In the second case, the stress falls on the first part of the compound word: it emphasizes the fact that "I am alone", "I am my own friend (and not someone else's"), the feeling of absence of someone else with me: "I am minus another". Thus, the word "self-friend" combines opposite meanings: both complicity (pole of identification)[Vygotsky, 1998] and distinctiveness (pole of individuation, distancing). This word is lost, but, phenomenologically, "self-friend" is present in people's consciousness and, with some semantic losses, is replaced by the word "we"[Vygotsky, 1999].

Obviously, the "we" conjecture owes its appearance to a deeply childish feeling, much earlier than the age of the mentioned preschoolers. S. Freud wrote about a spontaneous feeling, which, following R. Rolland, he called "oceanic". In his personal correspondence with Freud, Rolland spoke of "the simple and direct fact of feeling the Eternal, which is devoid of sensual boundaries" and is "as if oceanic..." [see 21].

V.S. Mukhina, significantly expanding the available lists of Jungian archetypes, turns to "archetypal symbols-meanings" that contain the meanings and implications of people's social positions in relation to each other: "they", "we", "Me", "Not Me", "Me and others". In this case, a special place in the "great ideopole of culture" is occupied by the archetypes of "they", "we", "Self" and "personality" [Mukhina, 2014].

Listening to the named symbols-pronouns, we recognize the fact of presence in us of the experience of deep commonality of these symbols, the unity of "Me-You-We-Them" in the feeling of the all-pervasive oceanic self, forming a special "archetype" underlying the others. At the same time, if a person realizes the previously unreflected sense of "We", "Me" and "You" are polarized in his consciousness. Thus, in the situation of saving a loved one, an illusion confirming the "theory of rational egoism" may arise, as if the person acted in his own selfish interests, although in the impulse he did not distinguish between himself and the other, experiencing community as such [Petrovsky, a][Ilyenkov, 1962].

This seems to be the key to understanding the "group agent". We discover a cross-existential community of different selves, an active unity based on the pre-reflexive "playback-living" of each participant's feelings, and, in this sense, the "convergence" of individual volitions into a collective will. Neither "centration" nor "decetration," but it is "We-Centration" (a special experience in which the distinction between "my Self" and "your Self" is removed) that forms the "substratum" of the collective subject.

And in this context, "I am" means a part of the collective WE, a group agency, a part of "allness".

The Theme of Immortality

Considering possible forms of existence of the transvital self, after the question of "transvital meanings", the researcher inevitably faces the question about the meaning of transvitalty itself and whether this meaning exists at all? The answer to this question proposed by the author is hypothetical and not empirically verifiable, but it also has intuitive and cultural-phenomenological grounds. This answer is: "Immortality", which forms the intentional commonality of the three distinguished hypostases of the transvital Self. The acquisition of "earthly immortality" has been considered by us earlier on the example of the need and ability of personalization [Petrovsky, 1981; Petrovsky, 1984]. But the theme of immortality in the context of the transvital Self is not limited to this. Each of its hypostases sets its own solution. Let us give some examples as material (and stimulus) for further research of the problem.

The supra-vital Self: a premonition of immortality. Let us limit ourselves here to two phenomenological discoveries of A.S. Pushkin from A Feast in Time of Plague:

All, all that threatens to destroy

Fills mortal hearts with secret joy

Beyond our power to explain—

Perhaps it bodes eternal life!

And blest is he who can attain

That ecstasy in storm and strife!

We emphasize here the paradox of transformation of the threat of death (interruption of vitality of being) into a pledge of immortality. A few more famous lines:

There’s rapture in the bullets’ flight

And on the mountain’s treacherous height,

And on a ship’s deck far from land

When skies grow dark and waves swell high,

And in Sahara’s blowing sand,

And when the pestilence is nigh.

Here too, Pushkin's "pledge of immortality" on the boundary between life and death, rapture on the boundary between "vital and lethal", a vivid example of the immortality of the transvital Self.

Meta-vital Self: immortality as otherness. Let us return to Tolstoy's words about a departed loved one. Does "his attitude to life always allow me to clarify my attitude to life"? Potentially - yes! However, of the people who inherit the lives of departed loved ones see in themselves the "growing power of life" of those who have left. What lesson can be drawn from what has been said regarding immortality?

This question is appropriate in a psychological counseling setting. The author's example from his own experience (the wording has been changed, the dialog has been transformed into a monologue, but the meaning is the same): "Your loved ones have left you, but they, you must agree, have become even closer to you now! - They live in you, do not prevent it. Do not listen to those who advise to say goodbye by "kissing", as some of my colleagues, transactional analysts, teach! Think what the departed would say to you now, if they saw you in suffering refuse to live, "in memory of your neighbor". And if you were able, let us say, to "voice" the voices of the loved ones who, having left, have now become closer to you, then in this case you would feel how important it is for you to live, because now not only you, but also the loved ones living in you demand it from you."

However, the true earthly immortality of those who have left, or rather "passed" into the lives of other people, the transvitalty that has taken place, implies something more than the active memory of those who are not physically around. It is important that "those who have left" know, feel that they remain (if this is achieved, who in this case would dare to claim that they do not exist? - Only strangers!). I believe that in childhood such an image of earthly immortality ("I will stay alive!") is possible at the level of feelings, not just rational anticipation. Future research should show whether, and in what periods of childhood, there is a special sensitivity of children towards the perception of this idea, - whether sensory periods for the formation of such anticipation-prediction can be singled out (the author does not touch upon here the problem of faith, immortality of the soul, in various religious confessions).

Cross-vital Self: immortality as all-existence. The sense of WE is not limited to the scale of dyads, triads, contact groups of any size. It extends beyond the space of physical interaction between people. A special phenomenon is contacts "through time" with those "far away" who are brought together by a common cause, interests, aspirations.

Thus, when a scientist makes a discovery, he, through space and time, "comes into contact" with those with whom he communicates (perhaps mentally), to whom he responds with his creativity and whom he himself is ready to develop in his works. The point of contact is the discovery itself. It unites a person not only with those who participated in the search, but also with the truth as such, which exists outside of time. For example, mathematical discoveries always reflect what pre-exists cognition. Conventionally speaking, Pythagoras' theorem existed before Pythagoras; the geometrical relations discovered by him were, are, and will always be; they do not reside in "created" (physical) time, but in "eternity" ("being, which has eternity as its measure, is not subject/agent to any change and is incommunicable with it," wrote the medieval philosopher Thomas Aquinas [Aquinas]. Now the scientist himself, as well as his predecessors, exist for him "through time".

Obviously, it is not only about the discoveries of philosophers, scientists, artists, poets. The same kind of phenomena includes the evidence of history that lives in people's memory, the phenomena of intergenerational continuity, the "legacies of old times", if descendants have not yet had time to betray them in response to the challenges of modernity.

This could remind the reader of V.I. Vernadsky's idea of "noosphere". But the analogy with the noosphere, the highest state of the biosphere, would have a purely external character in this case, not expressing the essence of the transvital Self. Geological (Vernadsky), and theological (E. Leroy, T. Tarden) ideas would be inappropriate here. Even less adequate in this context are references to occult practices, parascientific concepts, phenomena of clairvoyance, mesmerizing mysteries of "communication with the dead". The cross-vital Self, enclosing the idea of immortality, is the phenomenon of all-unity (all-existence) of people of different times and spaces, the feeling of community (oneness) of all with all, the experienced unity mediated by the "great ideopole of culture".

"The human spirit...penetrates with its spearhead into the past, into the future, into distant countries, ...is always paradoxical, always unexpected...a person can forget about his past...he can move to another city, he can change his name, he can change many things. But it will not kill him, because he himself remains, this is his "Self"” [Men].

There seems to be one common feature that unites all those who acquire the inter-spatial and through-temporal status of their being in the world. We dare to say it in this way: the surplus of life present in transvitalty:

Like a lost man wandering out of the wilderness.

wants to break free

so eager

MORE!

To make ends meet on a budget,

so that there's a balance

for immortality.

Necessary,

when the journey is over,

The surplus of life

to transcend.

The Sign of the Transvital Self

The idea of transvitality has always been implicitly present in culture, as an indication of a certain integrity, a special quality of human existence, but a word was needed to denote this quality.

It is possible that in time, in addition to the word "transvitalty", or, more precisely, the text as a "machine for producing meanings" (V.S. Sobkin), a visual sign of transvitalty will also appear, a new "stimulus-means" (L.S. Vygotsky) of believing oneself in being, which takes a person beyond the limits of his or her own limited relations with the world, a point of "assembly" of many and many - according to V.T. Kudryavtsev [Kudryavtsev, 2015]. For example, - such a sign (with comments in the right part of the diagram "Yin and Yang" and under it) (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4. Transvital Self (comments on the right side of the figure and under it)

[Aquinas] L.S. Akopyan thoroughly researched the fears of people at different stages of age development, and, what is especially important in the context of this review, the conditions of overcoming the fear of death in old age through the actualization of "transvital meanings".

[Akopyan, 2015] From V.P. Zinchenko's remarks about one of his colleague's works: "It was an impulse (according to Bergson), but by no means a breakthrough".

[Aristotle. Sochineniya v, 1975] We speak about authentic agency, because the term "agency, subjectivity", defined by us as causa sui [Petrovsky, 1992] and that gave the title of the doctoral dissertation, was practically not used by psychologists in those years, and today it is used in an extended sense, meaning purposefulness, arbitrariness, efficiency, etc.

[Asmolov, 2017] The history of active maladaptivity (boldness) of active science and education is a separate topic worthy of consideration. I know from the words of A.V. Petrovsky, as a historian of psychology, that at the funeral of V.A. Sukhomlinsky the higher authorities did not recommend talking about the "non-standard" views of the outstanding educator, but, to the credit of scientists, this instruction was not executed.

[Bogoyavlenskaya, 1971] It is natural to wonder if the author of the novel is not playing with himself in the person of a character. Is he not trying to confront himself? There is a great space for projections of all kinds of "experts", no matter how they call themselves - literary critics, literary critics, literary critics, personologists (Brudny [Brudny, 2003]), psychoanalysts or, as the author writing these lines, "personologists" [Petrovsky, 2003; Petrovsky, 2020; Pushkin, 1969]. The novel is dialogical, and its finale is not a point, but a question mark or an ellipsis.

[Brudny, 2003] We find a bold attempt to describe the phenomena of primitive culture in the context of active maladaptiveness in the book by A.A. Faradzhev [Shmelev, 2017].

[Vdovenko] The results of the empirical assessment of the prevalence of this phenomenon, the dependence on the age of children, etc. are preliminary, prompting the continuation of the master's research (interrupted for known reasons in the years of self-isolation between 2021 and 2022).

[Vygotsky, 1998] The term "complicity" has its own prehistory. With reference to Radishchev, it was proposed by A.V. Petrovsky [Petrovsky, 2000], as the semantic equivalent of what the author of these lines previously denoted as DGEI - "effective emotional group identification" (with the corresponding operationalization of the term). "This parameter," notes A. V. Petrovsky, "allowed us to identify the main components of the psychological characteristic of the phenomenon under study and already in itself contained its detailed description. Nevertheless, the interesting psychological phenomenon that stood behind it was labeled rather verbose. In search of a more successful designation, we turned to the notion often found in the philosophical works of the outstanding Russian thinker A.N. Radishchev - co-participation. The essence of co-participation is in active "co-enjoyment" and compassion. A.N. Radishchev wrote: "Having habituated himself to apply to everything, a man sees himself in the suffering and becomes ill.... A man is compassionate to a man, equally he will have fun with him". Co-participation is a specific type, one of the possible cases, modification of a more general category of interpersonal relations - collectivistic identification" [23, p. 106}

[Vygotsky, 1999] Moving towards "We", people leave the positions of "Me in you" and "you in me", and thus "not-Me" and "not-you" emerge, and the experienced "someone" in you and in me is the prototype of the Universal Self (Absolute), which takes various forms in culture; and among them is the "All-Seeing Eye", certifying a person in the reality (noomenality) of his or her Self.

[Ilyenkov, 1962] In our works [Petrovsky; Petrovsky, a] we noted the expediency of distinguishing the qualities of the "first" and "second" kind in the phenomenal field of an individual. Qualities of the first kind (geometrical representations, red, pain, etc.) do not undergo phenomenological transformation at the moment of reflexion; qualities of the second kind, like microobjects in physics, when becoming the subject of active research (reflexion), undergo certain changes: the thing being reflexed turns out to be not indifferent to the reflexion itself. A sense of community with the world (J.P. Sartre), including community with other people, can also belong to the category of qualities of the second kind. Both these and other qualities at the moment of reflexion can lead to the disintegration of the experienced fusion with the world, and in this process the subject-object relation or, respectively, Me and the other (others) is born.