Introduction

As evidenced by classical works [4, 6, 13, 15, 19] and modern studies [14, 17–18, 20], religion plays a significant but ambiguous role in human mental life and behavior. To comprehend the psychological significance of religion and identify the psychological mechanisms underlying believers’ behavior, it is essential to examine how various elements of doctrine and religious practices are represented in the minds of their adherents. Despite the fact that religious doctrine contains canonically defined ideas about the world order, the origin of humanity, the meaning of life, norms of social behavior, and so forth, the mental representations of its elements in specific individuals can vary considerably.

These few studies demonstrate that religious mental representations depend on the cognitive architecture of the mind and exhibit cultural “survivability” and success due to their counterintuitive nature, which challenges our intuitive expectations about objects of a certain type (people, animals, plants, etc.) [Boyer, 2000]. For instance, some religious narratives tell of an immortal man, a stone that speaks human language, a flying serpent with a fiery mouth, and so on. This is what makes them more memorable, attention-grabbing, and therefore successfully transmitted from generation to generation [Boyer, 2000].

J.L. Barrett and F.C. Keil’s experimental work with a sample of American undergraduates revealed the existence of two distinct types of human mental images of supernatural agents: theological and intuitive. Theological representations lead people to conceive of God as an entity existing outside of space and time. In experimental situations, however, they demonstrate intuitive (“theologically incorrect”) representations: God can be somewhere in the world, waiting for something to happen, spending time doing something, etc. [Barrett, 1996]. The same pattern has been confirmed in a sample of Hindu Bhagti [Barrett, 1998] and in a sample of Orthodox Christians[Kolkunova, 2017].

Furthermore, studies show that the activation of religious concepts generally leads to lower levels of uncertainty tolerance [Sagioglou, 2013]. This pattern varies according to the level of religiosity , as found by E.V. Ulybina and K.K. Klimova [Ulybina].

The concepts of paradise and hell are of significant importance within the tenets of various religious doctrines, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. These concepts embody ideas pertaining to the existence of two contrasting places and/or states of the eternal life of human beings. In religious texts, paradise and hell are typically presented in a metaphorical manner, with varying degrees of detail. In the Christian Holy Scripture (the Bible), the description of the concepts varies considerably.

Paradise is presented in different material characteristics and as the spiritual state of the believer – in two distinct forms: as the garden of Eden and as the kingdom of heaven/God. For example, paradise was originally described in the Old Testament as the garden “eastward” (Gen 2:8), in Eden, which existed on the earth, with a river flowing out of it, trees growing in it, including the tree of good and evil, and animals inhabiting it; in the garden of Eden, God placed man (Gen 2). In the New Testament, the interpretation of paradise is somewhat different. It is described as a place where one can “be with Christ” (Phil. 1:23) and as the kingdom of God, which is located within man, not outside of him (Luke 17:20-21). The apostle Paul writes, “The kingdom of God is not eating and drinking, but righteousness, peace, and joy in the Holy Spirit” (Rom. 14:17). At the same time, there is also such a description of paradise: “the holy city, New Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God… On this side of the river and on that was the tree of life, bearing twelve kinds of fruits, yielding its fruit every month. The leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations. There will be no curse any more. The throne of God and of the Lamb will be in it, and his servants will serve him. They will see his face, and his name will be on their foreheads. There will be no more night, and they need no lamp light, neither sunlight; for the Lord God will give them light. They will reign forever and ever” (Rev. 21:2; 22:2-5).

The concept of hell is associated with a number of characteristics, including “hell of fire/fire of Gehenna” (Matt. 5:22), “eternal fire” (Matt. 25:41), “eternal punishment” (Matt. 25:46), “lake of fire” (Rev. 20:14), “where their worm doesn’t die, and the fire is not quenched” (Mark 9:44), the lake of burning “fire and brimstone” (Rev. 21:8), where there is no rest day and night (Rev. 14:11), “no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom” (Eccl. 9:10).

Those destined for eternal damnation in hell will endure excruciating anguish and despair in the “outer darkness” where will be “the weeping and gnashing of teeth”. (Matt. 25:30).

This study aimed to elucidate the content of mental representations of paradise and hell in Orthodox Christians.

In the context of this research, mental representations are understood as a personal form of seeing what is happening based on individual experience of human interaction with the world [Kholodnaya, 2023]. Taking into account the hierarchical structure of representations [Prokhorov], in this study we focused on the associative and figurative/conceptual levels of mental representations of paradise and hell.

The general theoretical and methodological framework of the research is the Cultural-Historical (Cultural-Instrumental) Approach in the psychology of religion [Dvoinin, 2022]. In the context of this approach, religion is regarded as a product of sociocultural evolution and is conceived as a system of historically constituted cultural (semiotic) instruments that enable individuals to regulate their mental and behavioral processes. These cultural instruments can be designated as religious mental tools. They include:

a) religious objects (natural and artificial);

b) religious actions (rituals);

c) religious images (objectivized and personal);

d) religious meanings (concepts).

This approach posits that the operation of religious mental tools in real-life practice mediates a person’s life relations with the world, thereby transforming the actual psychological mechanisms of behavior regulation [Dvoinin, 2022]. The application of this approach to the analysis of mental representations of paradise and hell allows us to consider them as religious mental tools with the help of which Christians master their own psyche and behavior, mediating their relations with the world.

Additionally, the Construal Level Theory, as proposed by N. Liberman and Ya. Trope, serves as the theoretical framework for this study. This theory postulates a relationship between the personal experience of psychological distance in relation to an object (phenomenon) and the level of its construction in consciousness. In other words, the further away we perceive an object, the more abstractly it is represented in our consciousness. Conversely, the more personally close the object appears to us, the more detailed and concrete it is represented in our consciousness [Medvedev].

According to this theoretical framework, the degree of detail in the mental representations of paradise and hell will serve to indicate the extent of psychological distance experienced by Orthodox Christians in relation to these religious concepts.

Hypotheses of the study.

- Mental representations of hell are more detailed than representations of paradise in Orthodox Christians.

- There is a correlation between the level of religiosity and the degree of detail of mental representations of paradise and hell in Orthodox Christians.

- The mental representations of paradise and hell in Orthodox Christians, along with the characteristics canonically fixed in the Holy Scripture (the Bible), also reflect the cultural templates of perception of these concepts.

Methods

Design. The empirical study was conducted in several stages. Data collection was carried out on the Google Forms platform.

In the first stage, subjects completed a questionnaire which allowed us to identify: 1) the level of their religiosity; 2) the associative content of their mental representations of paradise and hell; 3) the figurative and conceptual content of mental representations of paradise and hell.

In the second stage, based on the diagnostic results, we detected “non-religious” subjects (their results were excluded from further analysis) and conducted a content analysis of the data obtained.

The third stage involved statistical processing, interpretation and qualitative analysis of the data. We evaluated quantitative and qualitative differences in the content of mental representations of paradise and hell. In addition, we searched for correlations between the level of respondents’ religiosity and the degree of detail of their mental representations of these religious concepts.

Sample. A total of 65 subjects who identified themselves as Orthodox Christians were included in the study sample. Participants were recruited through Orthodox online forums and religiously oriented groups on social networks. According to the diagnostic results, subjects identified as “non-religious” were excluded from the sample. The final sample for analysis consisted of 62 Russian-speaking subjects of Orthodox faith, residents of Russia (67.74% women and 32.26% men), age from 18 to 57 years (M = 34.32; SD = 11.03).

Tools and measures.

The Centrality of Religiosity Scale (CRS) developed by S. Huber and O. Huber [Kholodnaya, 2023] was employed to assess the level of religiosity of the respondents. The tool is a 10-item questionnaire that measures religiosity in five dimensions: intellectual, ideological, public practice, private practice and the respondent’s religious experience (on a Likert scale of 1 to 5). The final score on the CRS ranges from 1 to 5.

Method of directed associations was used to define the associative content of the mental representations of paradise and hell. Respondents were asked to cite the initial associations that emerged spontaneously for each concept – paradise and hell. The only limitation was the maximum number of potential associations – 15. The associations thus obtained were summarized into semantic units and subjected to frequency and comparative analysis.

Two versions of mini-essays were applied to reveal the figurative and conceptual content of the mental representations of paradise and hell (“What do you understand by the term ‘paradise’?” and “What do you understand by the term ‘hell’?”). Each mini-essay was proposed to be written in 3-4 sentences in free form. The texts of the mini-essays were subjected to content analysis, which resulted in the identification of semantic units – groups of similar characteristics that respondents assign to the concepts “paradise” and “hell”. These semantic units were defined as counting units and subsequently subjected to frequency and qualitative analysis.

Statistical methods. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the variables measured in the study, and the distributions were tested for normality using the Lilliefors-corrected Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. As not all of the variables were normally distributed, nonparametric statistical methods were employed for subsequent analysis. The differences in the detailing of the represented concepts “paradise” and “hell” were assessed using the Wilcoxon T-test. Cohen’s d was employed to ascertain the effect size. Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to find the correlations between the subjects’ religiosity and the degree of detail associated with the concepts of “paradise” and “hell”. Furthermore, we applied Fisher’s exact test (φ) to detect any differences in the frequency of figurative/conceptual attributes of paradise and hell. Data processing was conducted using the statistical software IBM SPSS 23.0.

Findings

The religiosity of Orthodox Christians. After excluding non-religious participants from the sample (who scored from 1.0 to 2.0 on the Centrality Religiosity Scale), the remaining 62 respondents were categorized as either “highly religious” (80.6%) or “religious” (19.4%). The mean of religiosity across the sample was found to be M = 3.411 with a standard deviation of SD = 0.634. Descriptive statistics for the distribution of religiosity are presented in Table 1. Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that the distribution of religiosity is normal (0.095, p = 0.200).

Table 1

Religiosity and Associations with Concepts “Paradise” and “Hell” in Orthodox Christians (N = 62): Descriptive Statistics

|

|

M |

SE |

Мe |

Mo |

SD |

As |

ASse |

Ex |

EXse |

Max |

Min |

|

Religiosity |

3,411 |

0,081 |

3,4 |

3,2 |

0,634 |

0,19 |

0,304 |

0,489 |

0,599 |

5 |

2,1 |

|

Number of associations with the concept “paradise” |

5,726 |

0,413 |

5 |

3 |

3,255 |

1,409 |

0,304 |

2,144 |

0,599 |

15 |

1 |

|

Number of associations with the concept “hell” |

7,694 |

0,468 |

7 |

5 |

3,682 |

0,315 |

0,304 |

-0,707 |

0,599 |

15 |

1 |

Associative level of the mental representations of concepts “paradise” and “hell” among Orthodox Christians. The total number of associations obtained by the sample was found to be 355 for the concept of paradise (M = 5.726, SD = 3.255) and 477 for the concept of hell (M = 7.694, SD = 3.682). Table 1 also presents the descriptive statistics of the corresponding distributions. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test indicates that both distributions are non-normal (0.201, p < 0.001 for paradise and 0.123, p = 0.021 for hell).

Differences in the detailing of concepts “paradise” and “hell”. Wilcoxon T-test revealed the significant differences in the degree of detail of concepts “paradise” and “hell” in Orthodox Christians. The mental representations of hell were found to exhibit a greater number of associative connections than paradise (T = –4.606, p < 0.001), suggesting that hell is represented as a more complex concept. Concurrently, the magnitude of the observed differences in detail (effect size) is above average, as evidenced by Cohen’s d = 0.566.

Correlations between the religiosity and the detailing of concepts “paradise” and “hell”. According to the results of Spearman’s correlation analysis, no statistical relationships were found:

- between the religiosity of Orthodox Christians and the number of associations with the concept “paradise”: rs = –0,129, p = 0,317;

- between the religiosity of Orthodox Christians and the number of associations with the concept “hell”: rs = 0,096, p = 0,459.

However, a direct significant relationship of medium strength was found between the number of associations with the concept “paradise” and the concept “hell”: rs = 0,647, p < 0,001.

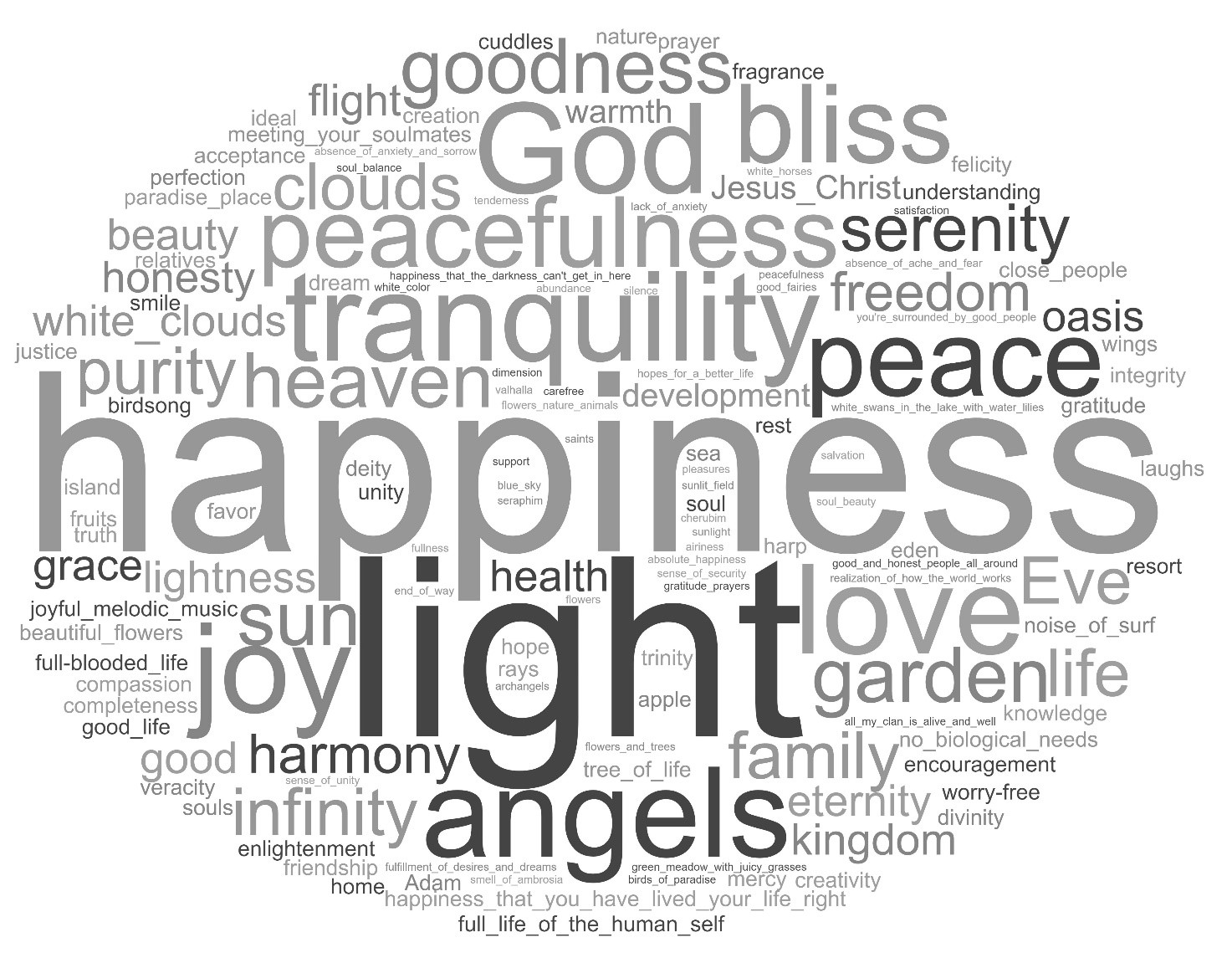

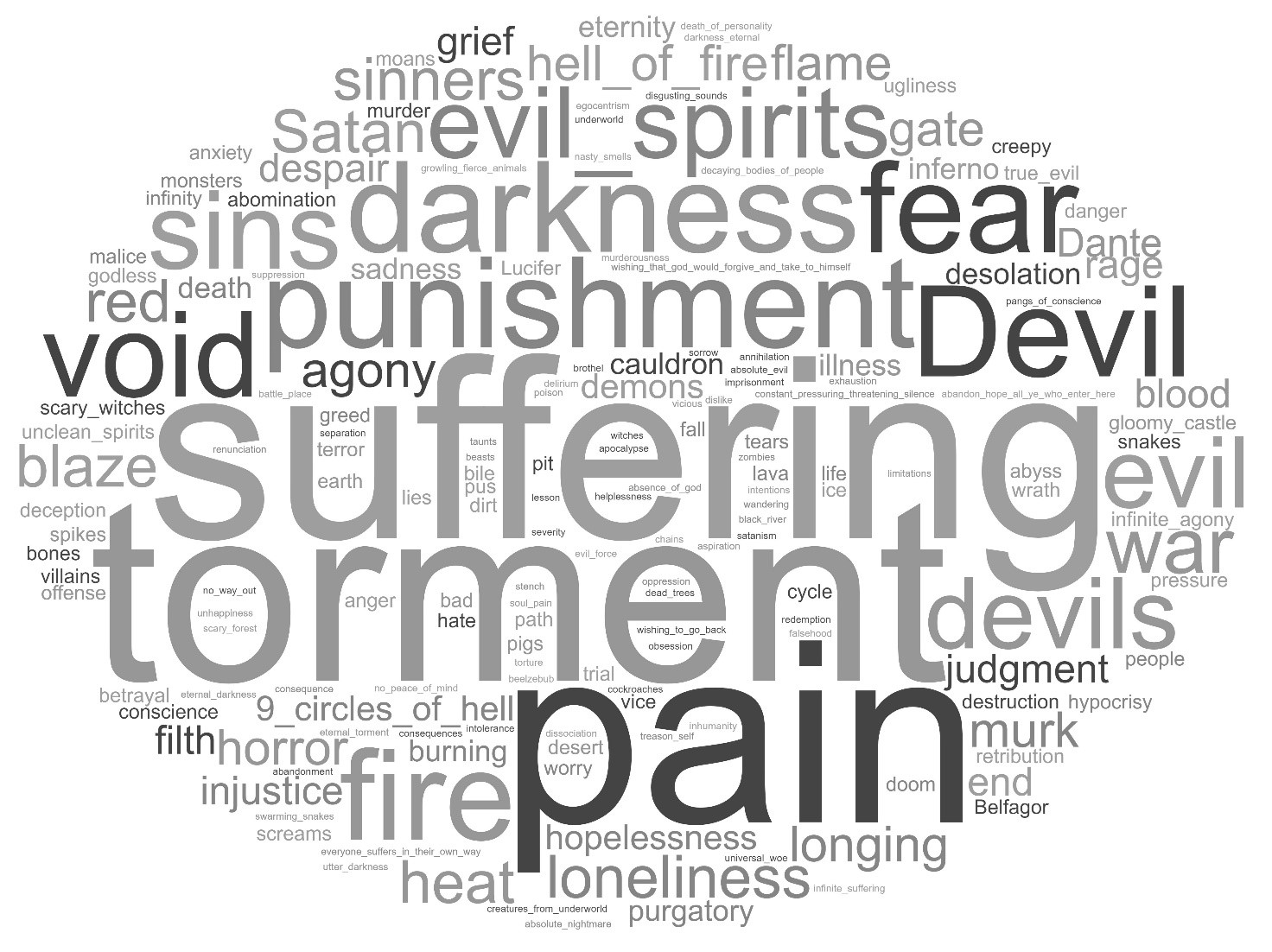

Frequency distribution of the associations with concepts “paradise” and “hell” in Orthodox Christians. For further analysis, the total number of associations (355 with the concept “paradise” and 477 with the concept “hell”) was reduced by combining words and expressions with the same meaning. Consequently, 145 unique associative units related to the concept “paradise” and 181 unique associative units related to the concept “hell” were obtained. Figure 1 and Figure 2 present the results of the frequency analysis in the form of word clouds.

Fig. 1. Associations with the concept “paradise” in Orthodox Christians: the size of words reflects their frequency

The concept of paradise is most frequently associated with the following attributes in descending order of frequency: light, happiness, love, tranquility, joy, angels, God, peace, peacefulness, sun, heaven, goodness, and garden. The most frequent associations with the concept of hell (in descending order of frequency) are as follows: pain, torment, suffering, fire, fear, punishment, darkness, Devil, sins, evil spirits, devils, 9 circles of hell, hopelessness, demons.

Fig. 2. Associations with the concept “hell” in Orthodox Christians: the size of words reflects their frequency

Figurative/conceptual level of the mental representations of concepts “paradise” and “hell” in Orthodox Christians. The content analysis of the participants’ mini-essays revealed the attributes belong to the figurative/conceptual content of the representations, which were then grouped into categories (Table 2). The most prevalent group of attributes, both for the concept “paradise” and for the concept “hell”, is “Emotional experiences”. This occurred in 80.6% and 59.6% of cases, respectively. The difference between the two is statistically significant (φ = 3.288, p < 0.001). It is notable that there is a similarity in the expression of such groups of features as “Spatial localization” (in 51.6% of cases for paradise and in 56.4% for hell; φ = 0.679, p > 0.05), “Temporal characteristics” (in 19.3% of cases for paradise and in 24.2% for hell; φ = 0.841, p > 0.05), and “External descriptive characteristics” (in 20.9% of cases for paradise and in 18.7% for hell; φ = 0.396, p > 0.05). The following groups of attributes were found to be specific for mental representations of the concept “hell”: “Bodily sensations and manifestations” (in 48.3% of cases) and “Beings” (in 40.3% of cases). These groups of attributes were not found in the figurative/conceptual content of mental representations of the concept “paradise”.

Table 2. Figurative/Conceptual Content of the Mental Representations of Concepts “Paradise” and “Hell” among Orthodox Christians (N = 62)

|

Category |

Attributes |

Concept “Paradise” |

Concept “Hell” |

Fisher’s exact test |

||

|

Indicators |

%* |

Indicators |

%* |

|||

|

Emotional experiences |

Indication of a specific affective phenomenon: an emotional reaction, state, attitude (feeling) |

Love, peacefulness, delight, tranquility, pleasure, harmony, kindness, joy, bliss |

80,6 |

Fear, suffering, desolation, loneliness, alienation, guilt |

59,6 |

3,288** |

|

Spatial localization |

Indication of place, location, extent in the physical sense |

Place, garden, oasis, heaven, sea |

51,6 |

Place, region, space, abyss, pit, bowels of the Earth, on Earth, gateway |

56,4 |

0,679 |

|

Temporal characteristics |

Presence of a temporal context (past, present, future), or its violations |

Eternity, infinity |

19,3 |

Eternity, infinity |

24,2 |

0,841 |

|

External descriptive characteristics |

Indication of external features (environment, situation, living conditions) |

Light (bright) |

20,9 |

Darkness, no light, murk, fire, flame, blaze, war |

18,7 |

0,396 |

|

Bodily sensations and manifestations |

Indication of physiological reactions and states of the body or sensory phenomena |

– |

– |

Pain, torment, agony, crying, hunger, moaning, screaming |

48,3 |

– |

|

Beings |

Description of agents (natural and supernatural) |

– |

– |

Sinners, Devil, Satan, demons, evil spirits |

40,3 |

– |

* The percentage of the total number of analyzed mini-essays of the respondents (N = 62) is indicated.

** Significance p < 0,001.

Discussion

The obtained results of measuring religiosity were expectedly higher in our sample than the average values for Russia as a whole, where M = 2.84, SD = 1.10 [Huber, 2018]. This can be explained by the principle of participant selection, which minimized (though did not exclude) the probability of non-religious subjects being included in the sample.

The analysis of the associative content of the mental representations of concepts “paradise” and “hell” among Orthodox Christians shows that at this (associative) level the representations of paradise are less detailed than those of hell. This confirms the hypothesis of the study about the differences in the detailing of representations.

Given that associative connections are regarded as manifestations of deep, poorly realized, and sometimes not realized at all contents of the psyche, it can be argued that the religious concept of hell, which is negative in its meaning (in the context of Christian doctrine), has a greater subjective value in the mental world (or rather, in the mental experience [Kholodnaya, 2023]) of Orthodox Christians than the concept of paradise. To summarize, regardless of whether the believer is aware of it or not, the threat of going to hell has a greater psychological significance (e.g., emotional or motivational charge) for him than the pleasant prospect of going to paradise.

From the perspective of the Construal Level Theory [Medvedev], the greater detail and specificity observed in the associative content of the mental representations of hell can be interpreted as evidence of experiencing (at an unconscious or weakly conscious level) a greater psychological closeness to hell than to paradise.

Upon examination of the most frequently occurring associations, it becomes evident that the representations of paradise and hell exhibit a multitude of interrelated characteristics. For instance, in both sets of associations, physical attributes (light for paradise; fire for hell), emotional attributes (happiness, love, joy for paradise; fear, hopelessness for paradise), supernatural agents (God, angel for paradise; Devil, evil spirits, demons, Satan for hell), and so forth, are highly expressed. It is also notable that the most frequent association with hell is a bodily (sensory) attribute – pain. Moreover, painful (bodily) sensations are included in other frequent associations with hell – torment, suffering. Among the most frequent associations with paradise, however, such attributes were not found.

This suggests that the religious concept of hell primarily evokes bodily experiences of psychological proximity to it among Orthodox Christians. This partly reflects the biblical notions of torment in fire, weeping and gnashing of teeth in hell.

The second empirical hypothesis concerning the correlations between religiosity and the detailing of the studied religious concepts is not confirmed. Apparently, differences in the detailing of represented paradise and hell, as well as in the experience of psychological distance to them, are related to factors other than the involvement of Orthodox Christians in religion. One such factor may be the different cultural load of these religious concepts (first of all, the wide representation of hell in works of art). For instance, the nine circles of hell are among the most frequently associated with hell. This is likely a consequence of the cultural influence of Dante Alighieri’s “The Divine Comedy” on this religious concept.

Concurrently, the significant correlation between the number of associations related to both concepts suggests that individual differences contribute to the degree of detail in mental representations. Those who produce more associations with paradise tend to produce more associations with hell, and vice versa. However, this relationship is moderate.

The analysis of the figurative/conceptual content of mental representations of paradise and hell reveals a notable prevalence of figurative elements over conceptual elements (despite the diagnostic task that allowed conceptual structures to appear). This fact is not surprising given that in the Holy Scripture (the Bible), as well as in numerous Christian literature, paradise and hell are described mainly in figurative, metaphorical form. For example, hell is described as “hell of fire” or paradise as “garden”, etc.

As we see, in general, the images of paradise and hell tend to be emotionally charged, the image of paradise – much more so than the image of hell. A number of facts merit particular attention. Firstly, there are bodily characteristics and various beings in the representations of hell, which are not observed in the figurative/conceptual content of the mental representations of paradise. The significance of corporeality in the representations of hell we also recorded earlier at the associative level. Secondly, the representations of such immaterial entities as paradise and hell are largely constructed using the attributes of matter, specifically spatial and temporal characteristics. This result is consistent with one of the key hypotheses supported by representatives of cognitive science of religion [10–12], namely that religious representations are determined by the functional capabilities of cognitive mechanisms of the mind. It is natural for human thinking to think in the categories of space and time, and these categories are employed, among other things, in constructing mental representations of supernatural entities.

The qualitative analysis of the figurative/conceptual content of the representations has confirmed the hypothesis about the presence of various cultural templates in them, along with canonical (biblical) notions. These templates are similar to those manifested at the associative level of mental representations – white swans; the nine circles of hell; a cauldron in which sinners are boiled; zombies; archidemon Belfagor; Valhalla – heavenly chambers from Germanic mythology, and so forth. Most of them relate specifically to the image of hell.

As we have already mentioned above, the cultural-historical (cultural-instrumental) approach to the psychology of religion [Dvoinin, 2022] posits that mental representations of paradise and hell can be considered religious mental tools that allow individuals to master their own psyche and behavior. This approach allows us to reveal the functional side of these representations. Although the functional side of the representations was not directly examined in the context of the present research, an investigation into their content and the specific characteristics of their organization may provide insights into this matter.

It can be reasonably assumed that the mental representations of paradise, which enable an individual to master their own psyche and behavior, function through the activation of an emotional experience associated with love, happiness, joy, tranquility, peace in a specific life situation. This activation occurs at both the unconscious (associative) and conscious (figurative and conceptual) levels. In addition to the activation of emotional experiences (such as suffering, hopelessness, loneliness, emptiness, etc.) for the regulation of behavior, mental representations of hell also actualize bodily experiences associated with a variety of painful sensations. Furthermore, the experiences and sensations associated with hell are more detailed and influenced by cultural templates, which makes hell psychologically closer (in the sense of psychological distance) to a person than paradise.

Conclusions

Upon completion of the study, the following primary conclusions can be drawn.

- Mental representations of paradise and hell among Orthodox Christians at the associative and figurative/conceptual levels reflect both the characteristics canonically fixed in the Holy Scripture (the Bible) and cultural templates. The basis of these representations is the Christians’ own predominantly emotional and, to some extent, bodily experience.

- Mental representations of hell at the associative level are more detailed than those of paradise. From the theoretical perspective, this can be regarded as evidence of an unconscious or weakly conscious experience of a less psychological distance from hell than from paradise among Orthodox Christians.

- The degree of detail of these religious concepts at the associative level is not directly correlated with the level of religiosity expressed by Orthodox Christians. Rather, it is likely influenced by other factors, such as the cultural load of the concepts, individual characteristics of Christians, and others.

- In the mental representations of paradise and hell held by Orthodox Christians, figurative elements are more prevalent than conceptual ones. Furthermore, the images of paradise and hell are predominantly emotionally charged, the image of paradise – much more so than the image of hell.

- From a functional perspective, mental representations of paradise and hell appear to serve as mental tools for regulating one’s own psyche and behavior. These representations seem to operate at the level of irrational regulation, primarily through the activation of emotional experiences (in the case of paradise) as well as emotional and bodily experiences (in the case of hell).

The limitations of this study are determined by a number of its peculiarities. Firstly, the research sample is specific — only Orthodox Christians and predominantly women. The imbalance in the sex composition of the sample, given its relatively small size, could contribute to a higher degree of expression of emotional components in the mental representations of paradise and hell. Secondly, the method of directed associations employed without temporal control fails to provide an opportunity to reach the implicit associative level of representations. Thirdly, the study fails to distinguish between the figurative and conceptual components of the representations. Fourthly, the conclusions about the functional side of mental representations of paradise and hell are hypothetical and require additional verification.

In our view, the most promising avenues for further research include the experimental verification of assumptions about the functional aspects of the mental representations of religious concepts “paradise” and “hell”, as well as the study of the associative content of these representations at the implicit level in the followers of different religious doctrines.

In practical terms, the findings of the study can be applied in the field of psychological counseling and psychotherapy of individuals with a Christian worldview to address psychological issues related to their moral behavior and ideas about life prospects.