Introduction

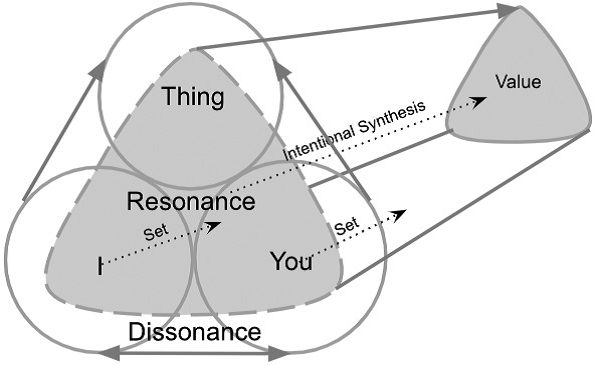

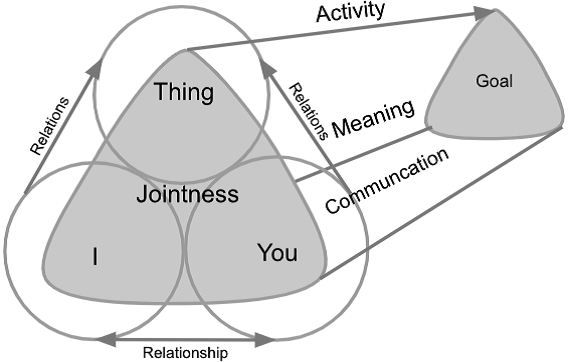

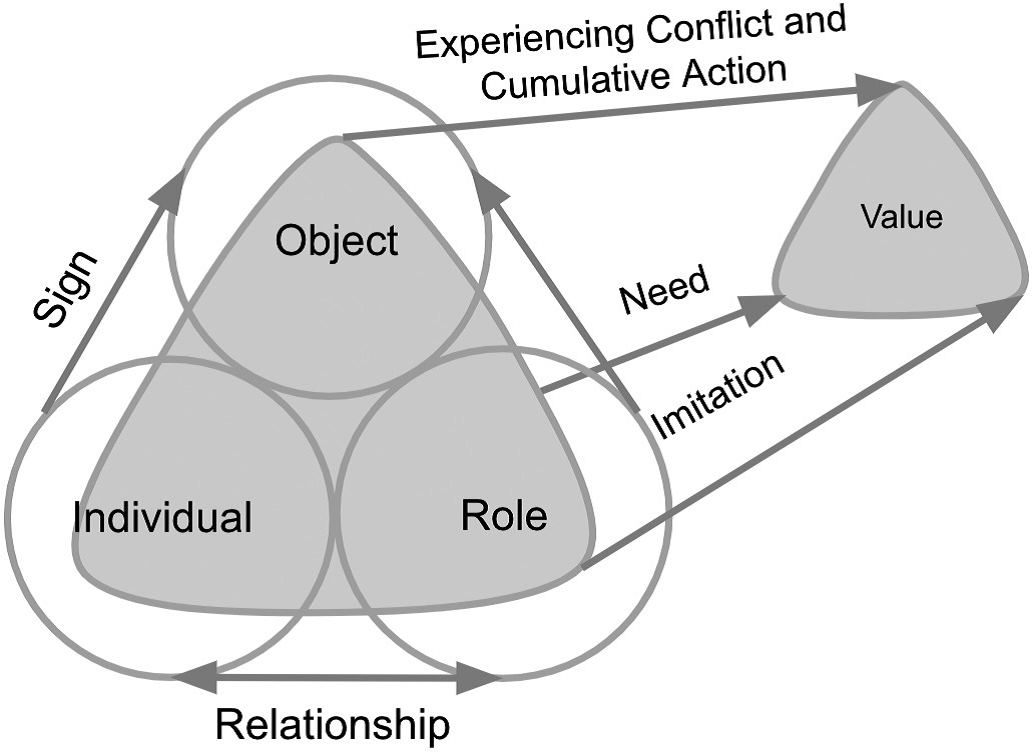

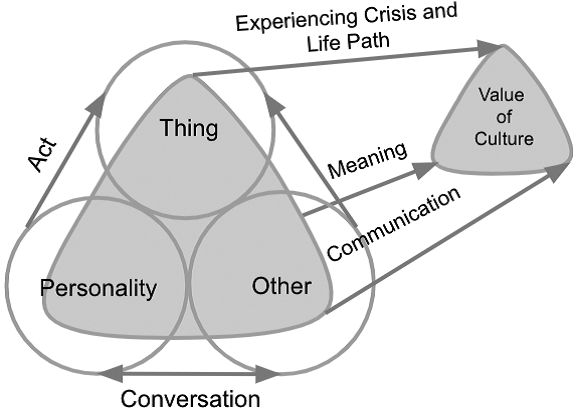

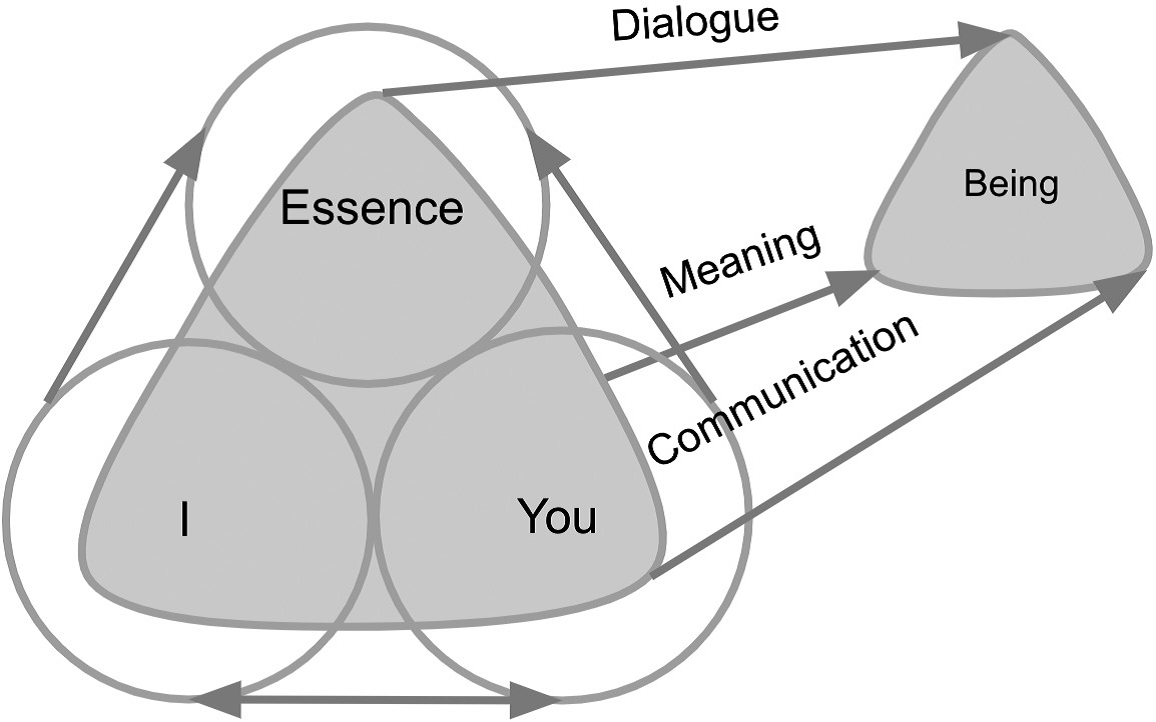

Continuing to consider jointness as a key general psychological phenomenon, we will try to understand its properties in more detail. The dynamic model of jointness generalises the achievements of cultural-historical psychology and develops the legacy of F.E. Vasilyuk (Василюк, 1984; Василюк, 2010). It includes structural and dynamic aspects of a human’s lifeworld, as well as captures its meaning development, and allows describing the processes of experiencing and meaningful activity resulting from successful experiencing (Fig. 1, 2). Nevertheless, so far our model is rather abstract.

We have previously defined jointness as “an integral phenomenon of interpersonal communication” (Мишина, 2010), as resonance and coordination between people, as a joint meaning field (Новичкова, 2024). But such a representation lacks the details that would allow us to look back at the whole of the human experience in question. Let us now try to understand how this phenomenon appears and manifests itself in our lives.

Let us assume that the development of jointness proceeds from simple to complex, from biology to culture, from its origins to developed forms. In this case, what is the initial form of the jointly shared fabric of meaning in human life? How does its development take place? Let us assume that initially meaning is “biological values” (Damasio, 2018, p. 37), “adaptive meanings” (Никольская, 2020) of the organism. And the fabric of meaning develops in the process of successive singling out within the human lifeworld of functional domains forming the phenomenon of jointness: I, Thing, Goal and You (Fig. 2; Новичкова, 2024). In what order, then, can this occur? We found a clue to the answer to this question in O.S. Nikolskaya (Никольская, 2020). The author considers the disorganising nature of childhood autism as a key to understanding normal, organising, human meaning development. And also in the works of F.E. Vasilyuk we find a detailed developed psychotechnical system (Василюк, 2010), which in many aspects complements the theory of O.S. Nikolskaya. Let us take the works of my teachers as a basis and try to reconstruct the general psychological regularities of the jointness development that emerge in them. As a result, the origin of jointness will appear as an evolutionary successive process of a human’s acquisition of the meaningfulness of their own life. Such a description will open up the possibility of studying the phenomenon in practice, and will also help to open up a discussion of the interconnectedness of various fields of human science with its help.

Materials and methods

A spectral and polyphonic (Цапкин, 2004) comparison of approaches from two areas of psychological practice — experiential psychotherapy and special psychology of childhood autism — was carried out. It was shown that the parameters of these typologies complement each other.

On the basis of psychotechnical methodology (Василюк, 2010), the processes that form the four levels of jointness organisation and the four degrees of meaningfulness of human life are described. The discussion incorporates references to evolutionary biology, neurobiology, and numerous aspects of human psychology, highlighting the strong interconnection between the phylogenetic development and ontogenetic processes of jointness.

Results

Proximity and difference between the two approaches

O.S. Nikolskaya identified four levels of affective (emotional and meaning) organisation of human behaviour and consciousness, which are formed in an unambiguously given order: “plasticity”, “affective stereotypes”, “expansion” and “emotional control” (Никольская, 2020). The adult in this approach is “...the centre of the child’s life situation, its mental organiser, mediator and conductor of cultural development” (Никольская, 2020, p. 163).

F.E. Vasilyuk described classifications from four modes of consciousness functioning, four types of critical situations and corresponding to them “dialogical internally” types of experiencing (perezhivanie) (Василюк, 2010, pp. 143, 155). These three classifications have not been fully correlated by their author, but it seems that they can be correlated (Василюк, 2010, p. 119). Let us try to consider them in unity.

O.S. Nikolskaya describes the “affective sphere” of a person based on her long-term practice of working with childhood autism and studying the history of human culture. The author stresses the “charge” of all human behaviour with adaptive meanings, describes the inseparable connection of cultural forms of behaviour with their “natural” basis (Никольская, 2020, p. 142).

F.E. Vasilyuk describes qualitative transformations of a human’s “lifeworld” with the help of phenomenology of everyday life and experience of clinical and psychotherapeutic practice, as well as using fiction literature. He speaks about the inseparable integrity of “human-life-in-the-world” (Василюк, 2010, p. 216).

Both authors strive to understand the human being on the way to meaningfulness. They are inspired by the works of L.S. Vygotsky, realising his ideas about the meaning structure of consciousness and the key role of experiencing. Both approaches grow out of the psychology of activity and rely on the category of “subject activity” (Никольская, 2020, p. 38; Василюк, 2010, p. 5; Leontiev, 1978). At the same time, from our point of view, they go beyond the framework of the activity approach, considering the Other as an ontologically significant entity (Бахтин, 2003).

The key difference between the approaches is found in the understanding of experiencing. For O.S. Nikolskaya, it is primarily “affective experiencing”, which “...reveals for the subject the adaptive meaning of what is happening”, “...modulates our consciousness and gives form to adaptive behaviour”. With its help “...needs maintain control over human activity” (Никольская, 2020, p. 6, 140). And for F.E. Vasilyuk, experiencing is primarily “the activity of experiencing”, a voluntary activity that is “aimed at producing meaning”, at “consolation, pacification” of the feeling-based foundation (Василюк, 2010, pp. 117-8; Василюк, 1984). That is, the differences in the theories consist in the focus of attention on the involuntary and voluntary sides of experiencing, respectively on the external and internal sources of regulation of the psyche (Fig. 1, 2; Vygotsky, 1978).

Thus, the approaches develop in a common field, although they follow different paths and describe functionally different aspects of experiencing. This allows us to consider them as fundamentally complementary, but not to make a direct translation of concepts. Let us try to organise the meeting of the two approaches in the coordinate space of the jointness model. This can help us to describe the processes of gaining meaningfulness of life quite fully (Fig. 1, 2).

Reconstructing the development of jointness

Let us consider the development of jointness from two perspectives — as an ontology of overcoming a critical situation and forming a fabric of meaning in activity, and as a phenomenology of meaningfulness emerging through the processes of experiencing (Leontiev, 2019; Новичкова, 2024). We will compare the typological parameters of the two approaches (Tab. 1) and, based on this comparison, describe four jointly shared “lifeworlds” (Vasilyuk, 2010).

Table 1. The levels of affective organisation of consciousness and behaviour according to O.S. Nikolskaya and types of lifeworlds, critical situations and modes of consciousness functioning according to F.E. Vasilyuk

|

Involuntary experiencing according to O.S. Nikolskaya |

Voluntary experiencing according to F.E. Vasilyuk |

|

N1.1 Adaptive meaning: plasticity |

V1.1 Infantile (vital) lifeworld |

|

N1.2 The subject is fitting into a living «timed» space, assimilating the rhythms of the environment |

V1.2 The Observer is passive and the Observed is passive |

|

Involuntary experiencing according to O.S. Nikolskaya |

Voluntary experiencing according to F.E. Vasilyuk |

|

N1.3 Peripheral consciousness |

V1.3 Mode of consciousness: Unconsciousness |

|

N1.4 A new affective parameter: Safe-Dangerous |

V1.4 Critical situation: Stress |

|

N1.5 Deepening contact with the world: Self-preservation |

V1.5 The psychological «unit»: Set |

|

N2.1 Adaptive meaning: Affective stereotypes |

V2.1 Values lifeworld |

|

N2.2 Subject fits the space into his/her motor pattern and links his/her life activities to the rhythms of the environment |

V2.2 The Observer is passive and the Observed is active |

|

N2.3 Magical consciousness |

V2.3 Mode of consciousness: Experiencing |

|

N2.4 A new affective parameter: Want-I don’t want |

V2.4 Critical situation: Conflict |

|

N2.5 Deepening contact with the world: Establishing order |

V2.5 Psychological «unit»: Relations |

|

N3.1 Adaptive meaning: Expansion |

V3.1 Realistic lifeworld |

|

N3.2 The subject dominates the space of the problem situation but is affected by time constraints |

V3.2 The observer is active, and the Observed is passive |

|

N3.3 Story consciousness |

V3.3 Mode of consciousness: Conscious awareness |

|

N3.4 A new affective parameter: Can-Can’t |

V3.4 Critical situation: Frustration |

|

N3.5 Deepening contact with the world: Achieving the goal |

V3.5 Psychological «unit»: Activity |

|

N4.1 Adaptive meaning: emotional control |

V4.1 Creative lifeworld |

|

N4.2 Subject loses affective immediacy, is modulated by the objective givenness of Others, voluntarily plans their actions in time and space claiming dominance |

V4.2 The Observer is active and the Observed is active |

|

N4.3 Awareness of necessity |

V4.3 Mode of consciousness: Reflection |

|

N4.4 A new affective parameter: Good-Bad |

V4.4 Critical situation: Crisis |

|

N4.5 Deepening contact with the world: Establishing emotional interaction |

V4.5 Psychological «unit»: Communication |

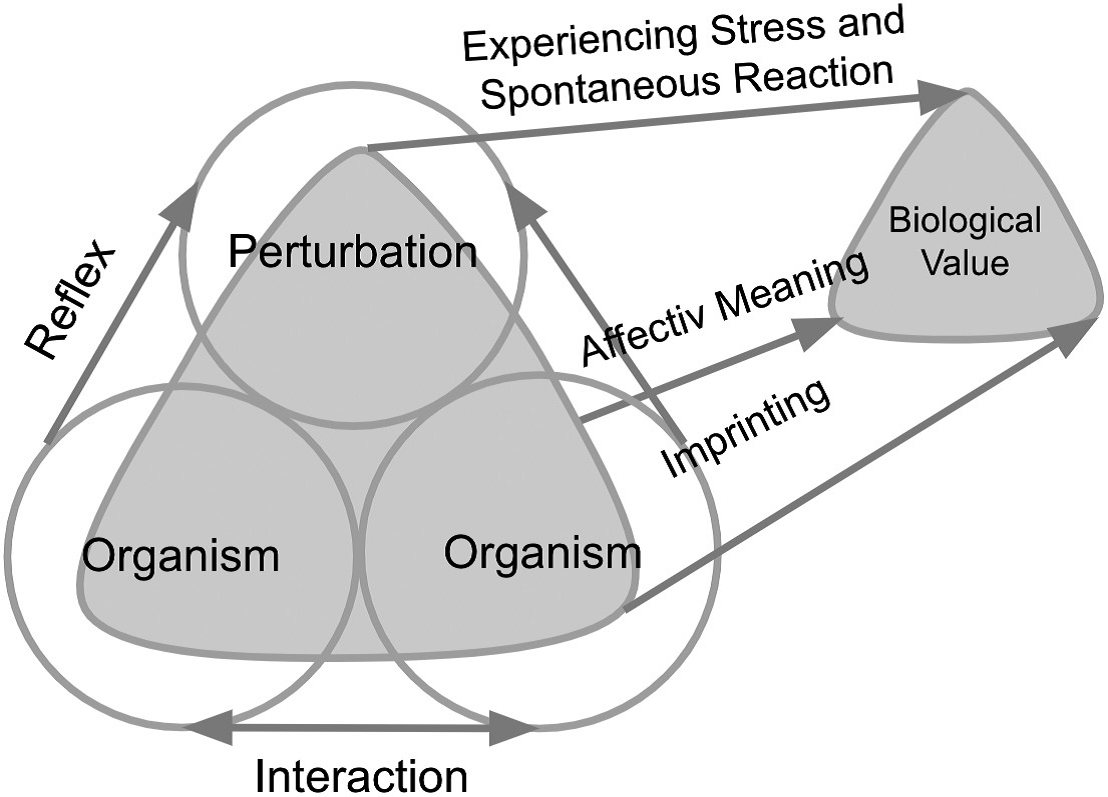

Biology: sensory-harmonic meaningfulness of safety

This first, most ancient, level of life organisation can be imagined in the form of the simplest single-celled creature that originated in the world ocean (Fig. 4). Safety (N1.4), preservation of integrity (N1.5), survival (Fig. 3) at this stage of development is the only “biological value” (Дамасио, 2018) for the organism, its “vital adaptive meaning” (Никольская, 2020). In the course of natural selection, those biochemical structures continue to exist that are able, undestroyed, to fit into the fluctuations of the environment (Fig. 3). Nascent in the “primary broth”, the organism first acquires integrity by means of the synchronisation of vibrational processes in different parts of the complex of randomly joined molecules (Kepa Ruiz-Mirazo, Briones, Escosura, 2014, p. 308). This primary resonance statistically increases its resilience to environmental influences (Ibid.) and allows it to start an evolutionary pathway — to develop a pre-emptive response to a potentially harmful perturbation (N1.2; Fig. 3). And the better this simplest biological structure tracks the periphery (N1.3) of its environment, the faster and more accurately it can respond to environmental changes (Fig. 3). The generalised non-specific stress (V1.4) response mobilises the formed integrity to provide a live-saving impulse to move in the direction from danger to safety (N1.4). This is what allows the organism to survive by dissolving into the impersonal force of the elements (V1.2; Fig. 4) and, together with its flows, to plastically (N1.1) circumvent the irregularities of space (N1.2).

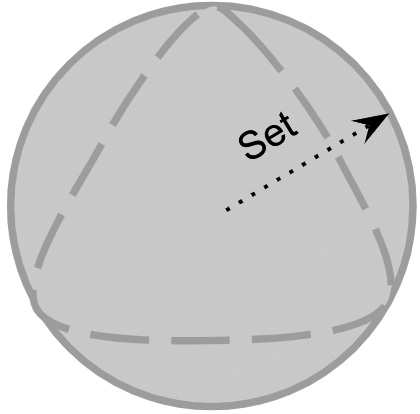

As organisms become more complex, systems of instantaneous response also develop. At the level of creatures like humans, this function is performed by innate and acquired reflex response systems (Fig. 3), automatisms, behavioural stereotypes, or, to use D.N. Uznadze’s term, sets (B1.5; Figs. 1, 4; Новичкова, 2024). Unconscious assessment of the environment and spontaneous response, automated skills and intuitive decision-making — all this allows the organism to quickly respond to environmental influences that threaten its integrity.

Comparing F.E. Vasilyuk’s typologies at this first level of development of jointness, we find that in the unconscious mode of consciousness (V1.3) there is “no place” for voluntary experiencing (Василюк, 2010, p. 123). From our point of view, this contradiction is resolved if we consider involuntary human activity as an integral operational basis of voluntary activity. Then involuntary, feeling-based, experiencing is also an activity to overcome a critical situation, because its methods were largely formed in the process of voluntary, active, experiencing (Василюк, 2010, p. 117).

The successful result of this felt experiencing is a merging with the environment, with its spatial organisation and rhythms. This is phenomenologically felt by a person, for example, as security and peace, harmony with nature, as dissolution in music or in the spontaneous pattern of dance movement, as unity with the world (Fig. 4).

What function does the Other fulfil for the human being at the first level of jointness development? If we return to the example of the simplest organism, we can imagine how accidentally synchronised or joined biological structures sometimes turn out to be together more resistant to environmental influences. Surviving through this symbiotic relationship, they consolidate and strengthen their community with new randomly acquired properties. This is how bacterial films, organelles within cells and multicellular organisms originate (Archibald, 2015; Flemming, 2016).

The human, as a deeply social being, already at this, involuntary, level of integrity in the flow, is capable of merging with the Other as part of the rhythmic pattern of the environment, of emotional contagion with the state of the Other. For example, in the form of “imprinting” (Bowlby, 1969) by a child of an adult’s “system of affective meanings” (Никольская, 2020). Synchronisation of physiological processes and attention with the Other (Tomasello, 2008; Feldman, 2007) allows it to enter the safe flow of shared perception, to assimilate the primary markup of the environment accumulated in the culture.

This preconscious transmission of physiological rhythms and behavioural reactions between people is indicated by many modern approaches: epigenetics and the theory of transgenerational trauma (Yehuda, 2009), gene-cultural co-evolution (Laland, Brown, 2002), studies of synchronisation between people (Nowak, 2017; Wlodarczyk, 2020) and others. In cultural-historical psychology, such fusion is evidenced by Vygotsky’s notion Pra-We (пра мы) and, for example, by A. Schwarz’s notion of intentional synthesis (Fig. 1; Schwarz, 2011). This involuntary resonance between people, this feeling of mutual trust and warmth, is considered by us to be an integral basis for all subsequent levels of jointness organisation.

Let us depict this involuntary, affective level of jointness organisation with a dotted line, meaning resonance with the Other as an impersonal element

Psyche: feeling-value meaningfulness of zest for life merged with the environment, in the process of formation of the sensory-harmonic meaning fabric of the human jointly shared lifeworld (Fig. 4).

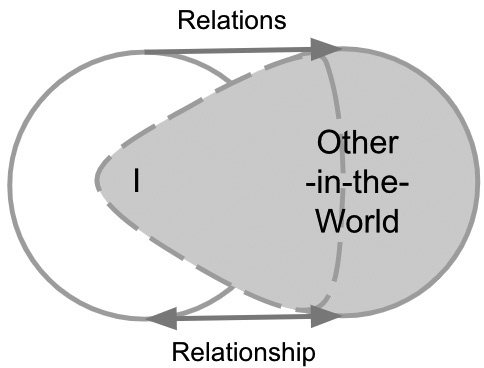

After survival, the simplest organism has the possibility of prolonging life and its reproduction. For this purpose, it develops systems for regulating the state of the internal environment of the organism, and needs appear (Fig. 5). To satisfy them, systems of prediction of changes in the internal environment are formed. It is still a form of anticipatory response to environmental changes, but now it involves tracking nearby objects and situational conditions (Fig. 5), as well as recognizing and capturing those objects that hold value (V2.1). The rhythms of the environment also begin to be evaluated in terms of their attractiveness (N2.2). When examining the environment, the characteristics of the detected object become signs of its value for the organism (Fig. 5). The living being starts to make individual passive selection (V2.2) of objects significant for it (N2.4). This selection is regulated by the expectation of internal biological feedback — the sensation of pleasure, confirming the correctness of the made choice (V2.4). This continuous information about the state of the organism’s internal environment becomes a class of sensations, feelings, that forming in the organism’s experience this particularly valuable internal entity, the “protoself”, the ancient precursor of the Self (Дамасио, 2018), our subjectivity. This is where the psyche originates.

At this meaning level, the person discovers the distinction between the internal environment of their organism and the external world — a distinction that is continuously reproduced in sensation as the separateness of the Self’s subjectivity from the objective world, from from the Thing, and the Other-in-the-World (Fig. 6). The internal environment acquires the significance of a reliable source of positive sensations. Body movements begin to be controlled by attention. A scheme of the body is built up — an image of its external boundaries (Bowlby, 1969). The felt experiencing, as soon as it arises, begins to be regulated by activity (V2.3) — it turns out that as a result of my action the state of the organism and my sensations change (Lange, 1885). This is how voluntariness, affective stereotypes (N2.1), coping with felt experiencing is born (В2.3), a zest for life emerges.

Let us specify that “infantile set” in F.E. Vasilyuk’s typology (B1.1; Василюк, 2010, p. 123) is oriented to the satisfaction of needs, so it should be considered as the affective basis of the value lifeworld (V2.1). Then the affective experiencing of the first meaning level (B1.1) should be labelled differently as “vital” (Василюк, 2010, p. 121). Vital and infantile experiencings are “light” and “simple” (Ibid.), but they differ in their biological values — orientation towards survival or lived experience. If a human experiences a vital threat, the stress response suppresses the body processes that interfere with survival. And a human’s dissatisfaction, if not life-threatening, leads to defining the need (Leontiev, 1978), to its satisfaction and can be described as a critical situation of conflict with the world (V2.4).

Also in our comparison of approaches, value experiencing (V2.1), according to F.E. Vasilyuk, turns out to be more primary than realistic experiencing (V3.1). This is not accidental. From the point of view of the visual logic of the development of children with autism, value is a means of forming the connectedness and constancy of the lifeworld (N2.5), it is a means of “...linking life relations (V2.5) into a single integrity” (Василюк, 2010, p. 126). It is the feeling of value, in a broad sense, that marks magically (N2.3) emerging objects of the world in the field of perception as desirable or rejected (N2.4). The gradually arising predictability of the appearance of valuable objects and knowledge of the ways of their appropriation form a sense of reliability of the jointly shared lifeworld before a human becomes ready to actively act in it (V3.2).

The main thing that gives protein structures an opportunity to prolong their life is receiving feedback from the world and from the internal environment of the organism by means of signs, signal molecules and other signs recognised by them (Kepa Ruiz-Mirazo, Briones, Escosura, 2014). The signs recognised by an organism can be considered as nodes of their internal coherence, on the human level they are, among other things, elements of their value system and cognitive structure. Signs expressed by a human in behaviour, including emotions and words, is a means of feedback in relationships. Thus, relationships appear as a consistent exchange of emotional and behavioural reactions (Fig. 5). And it is always “Not I”, the Other-in-the- World, who is active in them (V2.2; Fig. 6), and “I” responds anticipatively (Fig. 4).

Signs can be understood by the Other due to the shared context — the resonance of individuals’ attention and experience (Tomasello, 2008). The larger the circle of people who share the value denoted by the sign, the more the general features of this phenomenon come to the fore, while the private onesare levelled out. Thus, the sign is detached from the individual “feeling-based fabric” (Василюк, 2010, p. 178; Leontiev, 1978) and becomes a symbol (Кулагина, 2006). The more often a sign is used by people of a certain circle, the more obvious for them the general context of the use of this sign becomes. In this way, the understood symbolic meaning of a sign becomes an entry point to jointness (Fig. 6).

The other human at this feeling-value level is still a part of the world, but a special part of it. It is something similar to me, recognisable in my own sensations, but “Not Me” (Fig. 5). The significant Other, in forming a “secure attachment” (Bowlby, 1969), is felt as the very basis of the world predictability. And merging with the Other-in-the-World at this stage serves the new task of teaching the desired reliable action patterns, including the speech (Fig. 6).

Learning cultural stereotypes takes place through imitation (Bandura, 1986) of the attractive behaviour of the Other, behaviour that should help to satisfy a need — to resolve an emerging individual conflict (V2.4) with the world or with oneself. This occurs through the voluntary observation but involuntary appropriation of the desired behaviour of the Other, its visually observed role in transforming the world (Figs. 5, 6). The human imagines themselves as the Other, “reads” his skills and reproduces them in their own behaviour (Tomasello, 2008). From a neurobiological point of view, this is a “mirroring” (Rizzolatti, Craighero, 2004) “mental reflection” (Leontiev, 1978) of the Other’s behaviour with the connection of one’s own sensations to the emerging image by means of an “as-if body loop” (Дамасио, 2018). Reproducing a familiar part of an action combination in one’s own behavior and attempting to integrate newly observed elements into it enables the advancement of one’s skill within the “zone of proximal development” and the acquisition of new cultural experience (Vygotsky, 1978).

A human’s relations with the world are built largely as a result of independent activity. However, the acquisition of new behavioral forms through observation of the Other and participation in “сumulative аction” according B.D. Elkonin considerably extends our possibilities (Fig. 5; Эльконин, 2014).

In general, the activity of lived experience (Fig. 6) allows a human to experience pleasure from the practical visibility of the world structure (Piaget, 1954), from the order (N2.5) in the process of needs fulfilment. Thus, as a result of the process of learning from one’s own experience and the example of the Other, the system of signified values and skills of their acquisition generates a phenomenology of predictable pleasure and weaving an individual meaning fabric of zest for life.

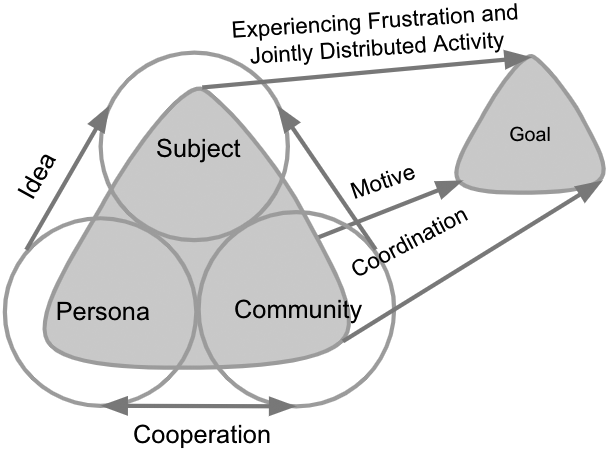

Society: realistic-narrative meaningfulness of accomplishment

At some point in evolution, the ability of living things to move in a directional manner moves to a new level. It is no longer just a generalised motor reaction to danger or a specialised reaction on a desired object, but the ability to actively physically move (V3.2) in its direction, to expand the availability of resources, expansion (N3.1). Thus the probability of meeting an object in the world is increased by the ability to plan one’s own behaviour. In the structure of the situation, the subject area of directed activity stands out, and the image of the desired object becomes its goal and value (N3.1; Fig. 7). Such expansion inevitably entails active influence on neighbouring organisms. And communities of organisms capable of coordinating such directed activity often find themselves at the top of the food chain (West, Griffin, Gardner, 2007). This is where social life originates.

At the human level, this ability to coordinate with the Other is reinforced by the ability to flexibly customize joint activities through a system of signs (Fig. 7). A sign is no longer just a tool for expressing reciprocal attitudes; it is now the main means of grasping the meaning of the community to which I want to belong. Special behavioural skills, language and a certain appearance are the signs of the subculture, which mark a human as their own, adjust the state and ways of cooperation of the participants, the discourse of the community.

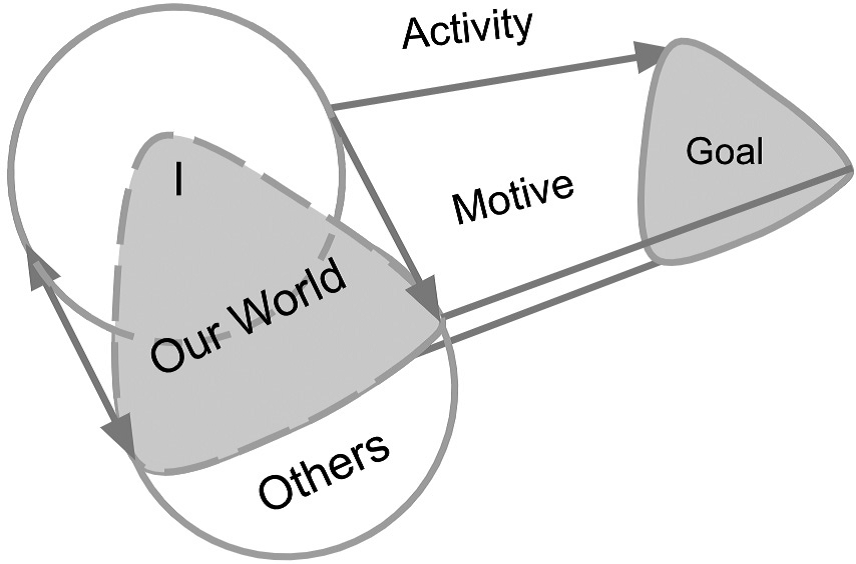

Whether it is a backyard company or a corporation, everywhere the transmission of meaning by symbolic means allows the community to prolong its story for almost any length of time, to keep the participants active until the ideal goal is reached, the realisation of a common idea expressed by a concrete result (Fig. 7). In this process, the symbol is filled with concreteness, and becomes an object-related abstract concept. For this purpose, “our” story is told (N3.3). How it is understood is crucial to the participants’ sense of community. Therefore, the conscious awareness (V3.3) of the story becomes the most important process of the community, forming the motivational system of its subject activity (V3.5), the fabric of meaning — Our World (Fig. 8).

The presence of Our world, “We”, logically implies its opposition to the world of Others, “Not We”. This neighbourhood is the group’s unifying factor. Clarifying the details of our commonality in relations with the Other allows us to form the outer boundaries of the community through negation, to formalise its integrity, especially when there is a lack of unifying peace-loving ideas.

Here, social selection of participants with the necessary qualities for the necessary role positions becomes a strong motivator for the individual to develop (Fig. 8; Islam, 2014). A person can expand the availability of valuable resources for himself through conquering the community by demonstrating his achievements (N3.2; N3.4). He becomes a social actor, a persona (Fig. 8) seeking recognition, striving for leadership. Motivated by the chance for personal success (Козунова, 2016) and supported in every possible way by community members in the process of overcoming frustration (V3.4) on the way to the goal, the human learns to maintain their own independent activity indefinitely. They become able to achieve the results they personally desire, to fulfil their own achievements (Fig. 8)

Culture: creative-existential meaningfulness of service

If we imagine the emergence of a multicellular organism in the process of evolution, we can imagine the gradual re-subordination of individual organisms and their groups to the tasks of a suprapersonal community. The more developed this community is, the more clearly it defines the parameters of functioning of individual cells, tissues and organs necessary to maintain the homeostasis of their coexistence (Fig. 9).

At the level of the human, such coherence is born gradually, in the process of dialogue (V4.5) of multiple voices, in the process of reflection (V4.3) of the path they have travelled, in the process of searching for criteria for assessing what is ultimately serves the common good and what is unacceptable. In this search, it is important that the common good is not substituted for the private good, nor is the unity of experiencing and opinion imitated, as happens in autocracies. It is only in a genuinely broad, trusting dialogue between the participants that agreement is born on the unshakable and flexible rules of this new community, on its cultural values and ethical principles. Such broad agreement gives rise, for example, to rules of politeness, biblical commandments, or the principle of the priority of the spirit over the letter of the law. Such internal coherence of a person forms their personal system of worldview, interpersonal understanding — friendship, and long-term reproduction of coordinated activity of many people gives rise to an institution.

The increasing complexity of a human’s external and internal sociality, its polyphony (Бахтин, 2003), leads to the need to increase the coherence of the systems of jointnesses to which they belong. The more integrated a human’s individual needs and the motivational systems of their communities are, the more satisfied and fully self-actualised he feels. And the many stories a person tells about experiencing joy and pleasure, about overcoming critical situations, as well as the responses they receive from an attentive and valuing listener, all merge into their inner image of their own personality. These dialogues give meaning to the personal narrative (N3.3; Зайцева, 2016), weave together perceptions of oneself as a significant member of society and, ultimately, allow one to feel oneself as an Author of culture.

A broad dialogue of I and You (Fig. 9) inevitably entails the restructuring of relationships and the destruction of established strategies of activity. Such a joint experiencing of crisis (V4.4; Fig. 9) can lead to interpersonal harmony only if there is mutual trust, recognition of the inalienable significance of each participant’s individual experiencing, and coordination of their judgments. All this opens up the possibility of being vulnerable to the Other. Such an active and mutually open experiencing allows finding creative (V4.1) joint solutions to the most complex, subtle and sensitive, including existential, issues. This сo-experiencing (Никольская, 2020, p. 115) calls for the participants’ ability to comprehend their emerging community itself, to rethink their life in it (Fig. 10). Appealing to the broad agreement that emerges in this process becomes a new common norm and value, a way of regulating co-existence (Fig. 9; Бахтин, 2003).

As a result, previously personal self-regulation begins to be subordinated to the consciousness of general necessity (N4.1; N4.3). Individual affective immediacy is lost (N4.2), but a special cultural spontaneity is born — a value-motivational-meaning system coordinated with the Other — service. Thus, “Man” becomes the “measure of things” (Fig. 9; Protagoras, 2025), given the trusted right to assess whether something is “good” or “bad” for our coexistence (N4.2; N4.4), implement cultural selection.

Whether it is an internal dialogue of an individual or a conversation in the family, in the community, at the level of the state or humanity, in any case the discussion enters the realm of philosophy, ethics and morality (Fig. 9, 10). Now the concern for jointness with the Other competes weightily with personal interests and priority can be given to one or the other decision only as a result of careful weighing of factors and arguments (Никольская, 2020, p. 113; Василюк, 2010). Thus, “Act” (Бахтин, 2003) becomes an expressor of this jointly shared, creative-existential meaning and forms the life path of a personality (Fig. 9).

Discussion of results

Our assumption about the connection between the domains of jointness, levels of affective organisation and types of critical situations has found a broad enough substantiation. However, significant clarifications were made: the functional domain “I” is phenomenologically distinguished in opposition to and simultaneously with the domain “Thing”; F.E. Vasilyuk’s infantile lifeworld serves as the affective foundation for the value lifeworld, and in the model of jointness development, it is replaced by the vital lifeworld

Conclusion

Thus, we proposed a hypothesis about the human meaning development through the successive singling out of functional domains within their lifeworld, which constitute the phenomenon of jointness. To substantiate it, we compared two cultural-historical theories of human meaning development and used them to describe four jointly shared lifeworlds. As a result, we obtained the bio-psycho-socio-cultural evolutionary model of the jointness development, of the four degrees of meaningfulness in human life (Tab. 2).

Thus, a rather slender general psychological picture of human development, one could say, a general anthropological vector, emerged.

The model with this level of detail can already be used as a rather convenient thinking tool in psychological practice. In addition, the work outlinesa space for a potential dialogue between different approaches to understanding the human being.

In general, saying that a jointly shared fabric of meaning, a feeling of jointness is the essence of the human in the person (Новичкова, 2024), it is worth specifying that the origins of the phenomenon of jointness lie in the general ability of living systems to form communities with different degrees and ways of integration. However, the special ability of humans for subtle and flexible tuning meaning communities, including through language, gives us the ability to carry out complex jointly distributed activities. And, ultimately, it allows us to feel jointness — to be guided by cultural meanings, overcoming the time constraints of our own lives.

Table 2. Levels of jointness development and degrees of human life’s meaningfulness

|

Layer of Being / Type of Selection |

Type of Biological Values |

Ontology of Jointness |

Fabric of Meaning |

Phenomenology of Jointness |

Degree of Meaningfulness |

|

Biology/ Natural |

Survival |

Environment |

Sensory-harmonic |

Integrity in the flow |

Safety |

|

Psyche/ Individual |

Lived experience |

Situation |

Feeling-value |

Pleasure predictability |

Zest for life |

|

Society/ Social |

Expansion |

Subject area |

Realistic-narrative |

Conquest by achievement |

Accomplishment |

|

Culture/ Cultural |

Coexistence |

Co-being |

Creative-existential |

Being co-experiencing |

Service |