Introduction

Situations of life change are characterized by momentum and uncertainty, and they are highly resource intensive, hence change is viewed as a type of difficult life situation (Bityutskaya, 2020; Bityutskaya, Dokuchaeva, Korneev, 2025). In Lazarus and Folkman’s theory, novelty, unpredictability, and ambiguity of a context, as well as temporal factors are considered as properties of a situation that determine its potential of being harmful, dangerous and threatening for the individual, thus requiring the activation of coping mechanisms (Lazarus, Folkman, 1984).

As we are interested in the role of cultural factors in the perception of life transitions, several aspects shall be highlighted that define the theoretical perspectives of contemporary cross-cultural research in this area. The cultural comparison most frequently used in the literature is based on the dimensions proposed by Hofstede (1980). This approach allows for quantitative comparisons and the determination of, for example, individualism or uncertainty avoidance in representatives of a certain culture.

Another aspect is related to the etic-emic approach, which provides for the identification of the universal (etic) and culture-specific (emic) components for any psychological phenomenon (Stefanenko, 1999). Thus, stress and the ability to cope with it are viewed as universal experiences people may have regardless of their cultural background. Yet, the perception of a stressor and the response to it, that is, goal setting and the choice of coping strategies, have cultural specificity (Kuo, 2011).

The third perspective looks into the mechanism used by individuals to link internalized cultural values to the process of stress appraisal as a factor in the coping dynamics and the perception of its effectiveness (Folkman, Moskowitz, 2004). Appraisals are viewed as “automatic products of learned rules of interpretation” and, therefore, are culturally prescribed phenomena embedded in the social context (Hobfoll, 2001).

The cultural-historical approach comprises the theoretical framework of this study; it defines mental functions as determined by the processes of humans interacting with the cultural environment (activities mediated by signs, symbols, and tools) (Vygotsky, 1982; Zavershneva, van der Veer, 2019). The cultural-historical theory considers cognition as a continuous process of mutual transitions between the poles of a “Person-Acting-in-the-World” system (Stetsenko, 2023). Culture sets patterns and “anti-patterns” of behavior that underlie an individual’s “self-understanding” in difficult life situations (Petrovsky, Shmelev, 2019). As noted in the study (Sokolova, 2012), research into the content and structure of the psyche, based on social and cultural conditions, as well as the structure of practical substantive activity, was an important outcome of using in psychology the cultural-historical approach developed by L.S. Vygotsky, A.R. Luria, and A.N. Leontiev. In particular, A.R. Luria showed the influence of cultural factors (the situation of rapid social change in Soviet Uzbekistan in the early 1930s) on cognitive processes and intellectual activity (Luria, 1982).

Cultural specificity of Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan is a multiethnic, multi-confessional country with a rich, complex, and collectivist culture. A focus on traditions, customs, and religion has been prevalent in the Uzbek people for many centuries (Jabbarov, 2007), which has been newly revealed in the last three decades. The collapse of the USSR, the new independence followed by socioeconomic changes, and globalization have become the scene of a unique clash of “Western” and “Eastern” cultures (Dadabaev, 2007; Ismailbekova, 2013; Kurbonov, 2019). Young people’s interest in the new values has catalyzed a revival of traditional education (Alizhanova, 2021). The community institution of the “mahalla” has moved to a new stage of development (Ismailbekova, 2013; Alizhanova, 2021).

The definition of the cultural levels of coping requires a description of the practice of patience, “Sabr,” that was primarily formed by the foundational principles of Islam, the most widespread religion in Uzbekistan. The highest form of this practice (“Sabr Jamil,” beautiful or noble patience) is mentioned in the Quran (Pavlova, Barieva, Bairova, 2018) and signifies endurance, fortitude, and trust in the will of Allah. The role of this practice in coping with situations of change is determined by two factors. On the one hand, the practice is efficient for preventing conflicts (Ismailbekova, 2013) and contributes to perceiving life’s difficulties as trials. On the other hand, it is used in the context of Islamic psychological counseling, which aims to influence an individual’s personality on three levels: “ruh” (soul), “nafsa” (the negative part of the human soul), “aql” (consciousness/mind), and “jism” (physical) (Pavlova, Barieva, Bairova, 2018). Pre-Islamic qasidas (poems), based on the technique of tahwil – shifting focus from negative aspects to positive ones – have a unique psychotherapeutic effect. In order to master this technique, a person should cultivate steadfast patience. Thus, “Sabr conquers dahr” (changing circumstances) (Rudakova, 2017, p. 24).

Coping at the individual levels in Uzbek culture is characterized by the unhurried actions, the use of planning strategies and “containing coping”, gender roles distributed in the process of overcoming life’s difficulties (Byzova, Chikurova, Molutova, 2013), and the search for social support (Agadullina, Belinskaya, Juraeva, 2020).

The aim and theoretical framework of this study

In this study, the cultural-historical approach is applied as an upper-level fundamental theory that provides a general explanatory framework and enables the development of theoretical propositions that can be empirically proven (Kornilova, 2023). Applied to the subject of change perception, the cultural-historical approach suggests that culture, through the models of coping with life’s difficulties adopted by its representatives, determines the content of representations (perceptions) of life situations and appropriate coping strategies. In particular, we propose that cultural models of acceptance or rejection of change include specific content depending on an individual’s cultural background. Moreover, this content is determined not only by quantitative characteristics but also largely by semantic features associated with social development and cultural and religious values. The general conceptual framework for the cultural determination of change perception is presented in Figure 1.

The cycle diagram demonstrates that cultural coping models determine the specifics of how an individual perceives their life changes. Depending on this perception, the person uses accordingly a specific set of coping strategies to manage the situation of change aligned with their cultural model. In this empirical study, we explore three combinations of coping strategies (focused on either accepting change or rejecting change, or those of an ambivalent profile, which combines the first two). We also examine the characteristics of change perception associated with each profile. The discussion of these results and their comparison with cultural values described in the literature, as well as with culture-inherent coping methods enable a further description of these cultural models.

The aim of this study is to identify the specific perceptions of change in representatives of Uzbek culture and their methods of coping with change.

Materials and methods

Participants

Two hundred seventy-nine participants, residents of Tashkent and other cities in Uzbekistan, took part in the study. The sample ranged in age from 18 to 64 years (mean age 26,1 ± 9,11), including 230 women and 49 men. Seventy-four percent of the participants reported Uzbek ethnicity, with the largest number of Russians and Koreans among the remaining participants. All respondents were fluent in Russian. Sixty-three percent of the study participants were students at Tashkent universities in various fields of study, while the remaining participants were workers in various professions. The data were collected online using the Testograf platform. The participants were informed on the study objectives, provided informed consent and then answered the questions. All study participants were provided with feedback on the study results.

In the second stage of the study, data from a Russian sample of 216 individuals aged 17 to 55 years (mean age 28,5 ± 9,8), including 182 women and 34 men (Bityutskaya, Dokuchaeva, Korneev, 2025), were used for cross-cultural comparison.

Methods

We used a mix of qualitative and quantitative research methods. The questionnaire “Types of Response to a Situation of Change” (TRSC, Bityutskaya, Bazarov, Korneev, 2021) was used to collect quantitative data. The 48 questionnaire items are grouped into seven scales related to the acceptance of life changes (scales: mastering change, overcoming difficulties, preferring uncertainty, and creating change) and the rejection or aversion to change (avoiding change, preventing change, and maintaining stability). The questionnaire items were rated on a Likert scale from 0 to 3 (least often, rarely, often, and most often).

In order to study the perception of change, responses to the following open-ended questions were used as qualitative data:

1. What environmental cues help you recognize that life changes are happening?

2. What signs of change are most important to you?

3. What helps you accept change?

4. How do you neutralize resistance to change?

The data collection procedure was consistent with the study conducted on a Russian sample (Bityutskaya, Dokuchaeva, Korneev, 2025).

Content analysis procedure

A codebook was used to analyze the qualitative data, including general categories and corresponding specific subcategories with their indicators. To enhance the reliability of the content analysis, 20 cases randomly selected from the dataset were independently coded by two experts. Upon reaching consensus on the discrepancies in data coding and reaching intercoder reliability, the remaining responses were coded. During the content analysis, seven general categories and 74 specific subcategories were identified based on the respondents’ responses

Statistical analysis

Latent profile analysis (Ferguson, Moore, Hull, 2020) was applied to identify groups with different proportions of response strategies according to the TRSC. Analysis of variance and pairwise comparisons with the Holm correction were used to assess differences in individual strategies across respondent groups. Results in the Uzbek and Russian samples were compared using the Mann-Whitney test. Calculations were performed in the R environment (4.3.3) using the software packages tidyverse (2.0.0), rstatix (0.7.2), and tidyLPA (1.1.0).

To determine the number of groups, models identifying from one to six clusters were evaluated, with each model evaluated under different assumptions regarding the (in)equality of variances and covariances of variables within the groups. Model comparisons were conducted using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The group size ratio and entropy were also taken into account.

Results

Latent profile analysis

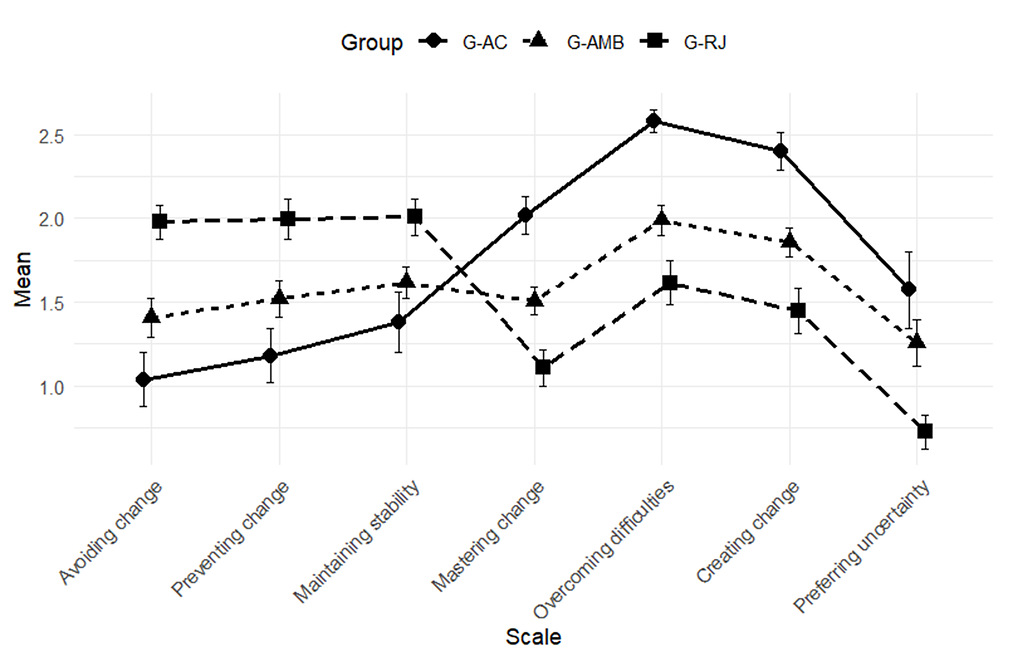

The model that identified three groups of respondents, assuming unequal variances and zero covariances between variables, was selected as the best model. The mean values for the TRSC scales in the groups identified in the Uzbek sample are shown in Figure 2. The number of subjects, their age, and gender distribution are presented in Table 1. Analysis of variance and pairwise comparisons revealed significant differences between all groups on all scales (p < 0,001).

Note: error bars are 2 standard errors of the mean.

The first group is characterized by relatively high mean scores on the Acceptance of Change scales and relatively low scores on the Rejection of Change scales (hereinafter, G-AC). The second group has average scores on all scales, which allows us to define it as a group of people with ambivalent attitudes toward change, combining both acceptance and rejection strategies (G-AMB). The third group had relatively high scores on the Rejection of Change scales and relatively low scores on the Acceptance of Change scales (G-RJ). In the study using a Russian sample (n = 216), three similar profiles were identified: G-AC (45 participants), G-AMB (111 participants), and G-RJ (60 participants).

Table 1

Size and composition of the selected groups in the Uzbek sample

|

Profile name and acronym |

Group |

N |

Male / Female |

Percent Male / Female |

Age |

|

Group with a profile of acceptance of changes G-AC |

1 |

84 (30,1%) |

16/68 |

19/81 |

27(9,1) |

|

Group with an ambivalent profile G-AMB |

2 |

115 (41,2%) |

22/93 |

19,1/80,9 |

25.9(9,1) |

|

Group with a profile of rejection of changes G-RJ |

3 |

80 (28,7%) |

11/69 |

13,8/86,2 |

25.4(9,2) |

|

|

All |

279 |

49/230 |

17,6/82,4 |

26.1(9,1) |

Note: mean age is given, standard deviations are in parentheses.

Descriptive statistics for the identified groups by content analysis categories are presented in Table 2. As can be seen from the table, differences across categories are small; a comparison of the three groups by these indicators using ANOVA revealed no significant differences between the groups across all categories (p > 0,05). However, this result was expected, as the characteristics of perceptions of the change situation enable the description of differences in the frequencies of specific subcategories.

Table 2

Descriptive statistics for content analysis categories in three groups

|

Category |

Profile |

||

|

G-AC |

G-AMB |

G-RJ |

|

|

1. External signs |

1,214 (1,213) |

1,165 (1,059) |

1,100 (1,001) |

|

2. Internal signs |

2,060 (1,826) |

2,165 (1,701) |

1,812 (1,170) |

|

3. Activity of the subject |

0,714 (0,800) |

0,678 (0,744) |

0,575 (0,671) |

|

4. Appraisal of change |

0,345 (0,630) |

0,183 (0,431) |

0,238 (0,534) |

|

5. Important signs of change |

1,024 (0,153) |

1,026 (0,160) |

0,988 (0,112) |

|

6. Ways to cope with a situation of change |

3,250 (1,597) |

3,522 (2,149) |

3,100 (1,228) |

|

7. Coping orientation |

1,000 (0) |

1,000 (0) |

1,025 (0,157) |

Note: averages for profiles are given, standard deviations are in parentheses.

The assessment of differences in the profiles of the Uzbek sample by subcategory

Table 3 presents the results of a comparison of the average frequency of responses, which allowed us to identify significant (p < 0,05) and marginally significant (p < 0,1) differences.

Table 3

Comparison of three groups of the Uzbek sample by frequency of subcategories

|

Category |

Subcategory |

Profile |

Significance of the differences |

||

|

AC |

AMB |

RJ |

|||

|

Internal signs |

Positive emotions |

0,119 (0,361) |

0,078 (0,270) |

0,025 (0,157) |

F(2, 276) = 2,387, p = 0,094, = 0,017 |

|

Negative emotions |

0,262 (0,583) |

0,339 (0,576) |

0,575 (0,652) |

F(2, 276) = 6,102, p = 0,003, = 0,042 |

|

|

Appraisal of change |

Positive appraisal |

0,095 (0,295) |

0,017 (0,131) |

0,038 (0,191) |

F(2, 276) = 3,463, p = 0,033, = 0,024 |

|

Ways to cope with a situation of change |

Inevitability |

0,143 (0,415) |

0,226 (0,441) |

0,300 (0,537) |

F(2, 276) = 2,365, p = 0,096, = 0,017 |

|

Distraction |

0,167 (0,406) |

0,330 (0,573) |

0,138 (0,381) |

F(2, 276) = 4,798, p = 0,009, = 0,034 |

|

|

Readiness for change |

0,190 (0,452) |

0,104 (0,307) |

0,062 (0,291) |

F(2, 276) = 2,846, p = 0,060, = 0,020 |

|

|

Coping orientation |

Oneself |

0,881 (0,326) |

0,835 (0,373) |

0,725 (0,449) |

F(2, 276) = 3,591, p = 0,029, = 0,025 |

|

On others |

0,036 (0,187) |

0,035 (0,184) |

0,125 (0,333) |

F(2, 276) = 4,098, p = 0,018, = 0,029 |

|

Note: the profiles are given as means, with standard deviations in brackets. The significance of differences was determined by the results of variance analysis.

Differences in the following subcategories were significant:

— Negative emotions. In the G-AC, the average frequency of mentioning this subcategory was lower than in the G-RJ (p = 0,003/0,0011) and G-AMB (p = 0,015/0,007). However, the G-RJ participants often noted that the change situation “causes discomfort”2 and “elicits distress.” In the G-AMB, the development of an anxious state was frequently mentioned.

— Positive appraisal. In the G-AC, the average frequency of this subcategory was significantly higher than in the G-AMB (p = 0,030/0,010). the G-AC participants identified scenarios that contribute to improvements: “my position in this world improves.”

— Distraction. In the G-AMB, the average frequency of this subcategory is significantly higher than in the G-AC (p = 0,034/0,017) and G-RJ (p = 0,017/0,006) groups. Moreover, G-AC participants mention more active ways of distractions, such as “sports” and “change of activity.” In the G-AMB responses, relaxation is also mentioned: “rest,” “watching films,” and “music.” In the G-AMB, this is associated with the theme of procrastination, as well as hope in fate and God. In the G-RJ responses, this subcategory is typically associated with “sleep” and “focusing on a hobby.”

— Orientation towards oneself. Respondents in all groups report reflecting on their experiences and attempting to accept the situation. Moreover, the average frequency of this subcategory was significantly higher in the G-AC than in the G-RJ (p = 0,029/0,010).

— Orientation towards others (seeking support). In the G-RJ, the average frequency of this subcategory is significantly higher than in the G-AC (p = 0,033/0,016) and G-AMB (p = 0,028/0,009). Analysis of the responses shows that the opinions of figures of authority and generally the “opinion of others,” as well as the desire to maintain reputation, are significant; the importance of maintaining relationships is noted.

Marginally significant differences were found for the following subcategories:

— Positive emotions. In the G-AC, the average frequency of mentioning this subcategory is higher than in the G-RJ (p = 0,090/0,030). The G-AC participants more often describe “excitement, anticipation,” and “a surge of strength and energy,” which are experienced positively.

— Inevitability. In the G-RJ, the average frequency of this subcategory is significantly higher than in the G-AC (p = 0,092/0,031). Acceptance of life changes in the G-RJ and G-AMB is facilitated by perceiving them as “inevitable,” as “a given that must be accepted,” as a situation associated with “the absence of another way out.” At the same time, one’s own potential is assessed as insufficient to influence the situation: “I understand that I cannot influence change,” “not everything depends on me.”

— Readiness for change. In the G-AC, the average frequency of this subcategory is significantly higher than in the G-RJ (p = 0,063/0,021). In terms of meaning, a distinctive feature of the G-AC is the responses associated with an experience of ease and “easy adaptation”: “It is not difficult for me to give up something routine and familiar in favor of something new and interesting.”

The assessment of differences between the Russian and Uzbek samples within subcategories

We further compared the frequency of subcategories in the responses of the Uzbek and Russian samples. Significant differences between cultural groups overall and within the three profiles are presented in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

Table 4

Comparison of samples by subcategories

|

Category |

Subcategory |

Samples |

Significance of the differences |

|

|

Russian |

Uzbek |

|||

|

Internal signs of change |

Negative emotions |

0,269 (0,588) |

0,384 (0,612) |

U = 26880,5, p = 0,008 |

|

Ways to cope with a situation of change |

Patience and removing resistance |

0,074 (0,28) |

0,143 (0,381) |

U = 28224,5, p = 0,023 |

|

Experience analysis |

0,361 (0,602) |

0,491 (0,667) |

U = 26761, p = 0,012 |

|

|

Distraction |

0,384 (0,607) |

0,226 (0,483) |

U = 26292, p = 0,001 |

|

|

Resistance to change |

0,051 (0,241) |

0,014 (0,119) |

U = 29167, p = 0,033 |

|

|

Coping orientation |

Oneself |

0,894 (0,338) |

0,817 (0,387) |

U = 27883,5, p = 0,024 |

|

On others |

0,023 (0,151) |

0,061 (0,24) |

U = 28993,5, p = 0,043 |

|

|

Withdrawing from the situation |

0,042 (0,2) |

0,1 (0,301) |

U = 28363,5, p = 0,014 |

|

Note: averages for profiles are given, standard deviations are in parentheses; the significance of the differences was determined by the Mann-Whitney test.

Differences between the Uzbek and Russian participants were significant in the following subcategories.

— Negative emotions. This subcategory was mentioned more frequently in the Uzbek sample than in the Russian sample (p = 0,008).

— Patience and removing resistance. This subcategory was mentioned significantly more frequently in the Uzbek sample than in the Russian sample (p = 0,023); this result was replicated when comparing the G-AMB profiles (p = 0,012), see Table 6. Among the Russian participants, statements about neutralizing resistance often imply willpower and cognitive effort, mentioning the need to overcome the situation “by forcing oneself.” Participants’ statements in the Uzbek sample contain the meanings of “a need to endure” and overcoming one’s resistance: “negotiating with oneself,” “finding ways to neutralizing resistance.”

— Experience analysis. In the Uzbek sample, the frequency of this subcategory is higher than in the Russian sample (p = 0,012), which is characteristic of the G-AC (p = 0,027). Uzbek G-AC respondents more often mention reflecting on their own states: “I try to understand what causes my resistance,” “I analyze my fears.” Meanwhile, the Russian G-AC respondents primarily rely on rational arguments.

— Distraction. The frequency of this subcategory was higher among Russians (p = 0,001), which was also found when comparing the G-AC (p = 0,003) and G-RJ (p = 0,019) groups. Russians more often use distraction as a form of cognitive and emotional disengagement, as well as “getting absorbed in work.” The responses of the Uzbek cultural group were dominated by “rest,” “peace,” “creativity,” and communication with loved ones; “absorption in work” is not used as a form of distraction.

— Resistance to change. The frequency of this subcategory was higher among Russians than among the Uzbek cultural group (p = 0,033), as was also found in the G-RJ (p = 0,004). Among Russians (most often G-RJ), resistance to change was emphatically expressed as “I resist to the last.” Many Russian participants noted the prolonged and intense nature of their resistance: “I won’t accept [change] for a long time.” The Uzbek G-RJ responses do not include the resistance category, but the overall sample does contain isolated statements in a more moderate form: “Depending on the outcome, if I am not satisfied with the result, I will look for other options.”

— Orientation towards oneself. Overall, the frequency of this subcategory is higher among Russians than in the Uzbek sample (p = 0,024). Differences were also observed in a cross-cultural comparison between the G-AMB (p = 0,05) and G-RJ (p = 0,011) groups. At the same time, this subcategory is found in both samples and is largely consistent in content, describing internal attempts to change one’s perception of change.

— Orientation towards others (seeking support). The frequency of this subcategory is higher in the Uzbek sample’s responses compared to the Russians (p = 0,043). The content analysis of the responses shows that representatives of the Uzbek culture find family and community support relevant when accepting change: “conversations with loved ones,” “feeling of security through contact with others,” and “examples of other people.” Respondents describe how the opinions of loved ones influence their own perceptions of change. Russian respondents also mentioned significant others, but the semantic contexts often differed: “the thought that other people are also undergoing changes is helpful,” “a psychologist helped.” It is also important to note that such responses are not typical in the Russian sample.

— Withdrawal from the situation. In the Uzbek group, the frequency of this subcategory is higher than in Russians overall (p = 0,014) and in the G-AMB (p = 0,002). Semantically, the similarities between the Russian and Uzbek samples are manifested, firstly, in the recognition of the role of time: “time helps to accept changes.” Secondly, strategies of distraction and relaxation are frequently used. Thirdly, support from loved ones or trusted people is noted. However, the methods of necessary support and specific methods of distraction vary (see the corresponding subcategories above).

— Change in internal sensations. In a cross-cultural comparison of G-RJ, the frequency of this subcategory is higher in Russians (p = 0,02). They predominantly describe internal changes through “inner experiences.” A characteristic feature of the G-RJ in the Uzbek sample is the mention of “inner peace” as a resourceful state.

— Self-development. The frequency of this subcategory is higher in the Uzbek G-RJ than in the Russian G-RJ (p = 0,036). In Russians, this subcategory characterizes the G-AC, while in the G-RJ it is found in separate cases.

Table 5

Comparison of samples by groups

|

Category |

Subcategory |

Samples |

Significance of the differences |

|

|

Russian |

Uzbek |

|||

|

G-AC |

||||

|

Ways to cope with a situation of change |

Experience analysis |

0,222 (0,471) |

0,488 (0,685) |

U = 1523,5, p = 0,027 |

|

Distraction |

0,489 (0,727) |

0,167 (0,406) |

U = 1450,5, p = 0,003 |

|

|

G-AMB |

||||

|

Ways to cope with a situation of change |

Patience and removing resistance |

0,054 (0,227) |

0,165 (0,396) |

U = 5725,5, p = 0,012 |

|

Coping orientation |

Oneself |

0,928 (0,322) |

0,835 (0,373) |

U = 5807, p = 0,05 |

|

Withdrawing from the situation |

0,018 (0,134) |

0,122 (0,328) |

U = 5720,5, p = 0,002 |

|

|

G-RJ |

||||

|

Internal signs of change |

Change in internal sensations |

0,367 (0,52) |

0,188 (0,424) |

U = 1983,5, p = 0,02 |

|

Ways to cope with a situation of change |

Distraction |

0,317 (0,537) |

0,138 (0,381) |

U = 2018,5, p = 0,019 |

|

Self-development |

0,033 (0,181) |

0,138 (0,347) |

U = 2150, p = 0,036 |

|

|

Resistance to change |

0,117 (0,372) |

0 (0) |

U = 2160, p = 0,004 |

|

|

Coping orientation |

Oneself |

0,9 (0,303) |

0,725 (0,449) |

U = 1980, p = 0,011 |

Note: averages for profiles are given, standard deviations are in parentheses; the significance of the differences was determined by the Mann-Whitney test.

Discussion

In this study, we examined ways of perceiving and coping with life changes as exhibited in individuals from the Uzbek culture. In the first stage of comparison, three groups with different change profiles were identified. The group with the profile of rejection of change most frequently (compared to the other identified profiles) mentioned negative emotions and assessments of situations of change, as well as the inevitability of such situations as contributing to the acceptance of change. It is important that the period when change is not being accepted and must be endured is perceived as significant for self-development. For the G-RJ profile, a focus on other people was also revealed, such as seeking support from others and turning for advice to figures of authority. The group with the ambivalent profile more frequently mentioned distraction, as well as negative emotions (as compared to the G-AC profile). The group with the acceptance of change was distinguished by a higher frequency of mentioning positive emotions and assessments of change, readiness for change, and orientation towards oneself. The latter is manifested in focusing on one’s own experiences, analyzing the experiences, and searching for positive opportunities in a new situation.

In the second stage, we conducted cross-cultural comparisons for the two cultural groups. Overall, the observed differences in perceptions of change among Uzbek individuals (compared to Russians) were associated with more frequent mentions of collective coping strategies and the “need for patience,” along with a greater focus on self-reflection. Yet, resistance is mentioned less frequently, indicating that the Uzbek sample was more likely to accept the conditions of a situation of change. While resistance to change (as a struggle to “return everything to the way it was”) was found to be significant for the Russian G-RJ (Bityutskaya, Dokuchaeva, Korneev, 2025), this theme was not present in the responses of the Uzbek sample. Instead, an external locus of control predominates, viewing change as objectively determined circumstances that are difficult to influence. This further facilitates acceptance of change. Another important result was discovered when comparing the Russian and Uzbek groups with ambivalent profiles. The Russian group often demonstrated a tendency to shift from rejection to acceptance of change, using positive reappraisal as the key coping strategy (Ibid.). The Uzbek group reports coping strategies of distraction and postponement of making a decision, with distraction aimed at calming down and communicating with loved ones. The obtained results are consistent with a strategy called “containing coping” (Byzova, Chikurova, Molutova, 2013).

These trends can be seen as a reflection of the collectivist culture and the Islamic value of patience, “Sabr”, characteristic of Uzbek culture (Pavlova, Barieva, Bairova, 2018; Ismailbekova, 2013). Overall, the Uzbek sample was dominated by a focus on the need to adapt to the conditions of a situation, adjusting to them despite internal difficulties, indicating a flexible approach to change.

Coping methods that are defined as “passive coping” and “problem avoidance strategies” (distraction, postponing decisions and actions) in the American-European system of categorizing coping strategies, appear imbued with different meanings in the Uzbek mentality. This is associated with the value of steadfast, noble patience (“Sabr”), which subsequently helps cope with and accept change. In other words, the same external manifestations of coping may have different meanings in Western and Eastern cultural models.

However, in this study, we also obtained results identifying a universal component. The cross-cultural comparison of the perceptions of change by the participants assigned to the profiles of accepting or rejecting change reveals some common features, along with the differences. Similarities are obvious in the valence of emotions and assessments, which can be attributed to universal characteristics (Stefanenko, 1999). However, this conclusion requires verification in samples from other cultures.

Conclusions

This study provides for the description of a model of coping with life changes typical for Uzbek culture, characterized by gradual acceptance of the situation and flexible adaptation to its conditions, as well as collective coping methods. The associated characteristics of perceiving change are described by the need for patience. This is defined as persistent and noble coping, including with the negative emotions that arise when change is not accepted. While Russians in similar situations often need to look for positive aspects and benefits in changes, and find encouragement to accept them, residents of Uzbekistan often need time to slowly and deliberately adjust to the situation and reflect on their experiences of interacting with it. Distractions include methods for achieving calm and a focus on one’s inner world, and the opportunity to communicate with loved ones.

The research framework of the cultural-historical approach was instrumental in analyzing the cultural models, and the specifics of perceiving change and coping with it as a holistic structure.

Limitations. 1. In this study, we did not analyze gender differences due to the disproportionate number of men and women (for the Uzbek sample 18% / 82%, for the Russian sample, 16% / 84%, respectively). 2. We also did not consider the substantive features of change situations (what sphere of life they relate to).

1 From here on, the first significance value is provided with the Holm correction, the second significance value is uncorrected. The significance of differences is discussed as adjusted for multiple comparisons; however, given the exploratory nature of this study, we considered it important to also present the uncorrected significance as an indication of potential significant differences.

2 Excerpts from respondents’ responses are provided in quotation marks.