Introduction

Impairments in social skills are one of the core characteristics of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). These impairments may emerge as establishing eye contact, responding to joint attention, initiating social communication, and using appropriate gestures starting from early childhood

[Davis]. Moreover, impairments in social skills may not naturally decrease or disappear over time. Rather, they become more pronounced unless appropriate interventions to promote social competence are delivered to these individuals

[Gates]. Thus, individuals with ASD require direct, systematic, and planned social skills training throughout their life

[Reichow].

There are several treatments found to be effective in applied research for individuals with ASD

[Wang]. Some common characteristics of these interventions include operational definition of target social skills and context, use of visual supports, and implementation of the treatment in 1:1 or group instructional format in typical settings

[Krasny]. One of the treatments that carry these characteristics is story-based intervention. Story-based interventions, also called social narratives, consist of a short story, a script or a scenario using the first- or third-person perspective with a visual support that can be used to teach individuals with ASD social skills or assist them in responding appropriately in confusing social situations

[Steinbrenner, 2020].

As a hypernym, story-based interventions have been defined as an evidence-based practice in technical reports

[National Autism Center, 2015; National Professional Developmental, 2014; Steinbrenner, 2020]. However, there have been review papers warning against the implementation of story-based interventions due to a lack of empirical evidence and highlighting the need for additional research for interventions that fall under the hypernym for story-based interventions such as Power Cards [e.g., 24; 39].

Gagnon’s Power Card procedure

[Gagnon, 2001] explicitly teaches children how to behave appropriately in a specific social context through two instructional components, a script and a Power Card. What makes it distinctive from the other types of story-based interventions is that it incorporates the child’s special interests into the intervention. The Power Card procedure typically consists of five components as follows: (a) a short script developed at the child’s comprehension level that centers on the child’s special interest and the behavior or context that is troubling, (b) a visual support relevant to the child’s special interest, (c) a short script about the child’s special interest attempting a solution to the situation that is problematic for the child, (d) a short three- to five-step strategy outlining the problem-solving method used by the special interest regarding the behavior or context that is troubling for the child, and (e) a note of encouragement for the child to exhibit the new behavior

[Gagnon, 2001; Keeling].

In literature, only a handful of studies have examined the effects of Power Card procedure to increase social skills or decrease problem behaviors of children with ASD [e.g., 7; 12; 13; 43], and reported positive outcomes. Although these studies have produced promising results, additional research is needed to investigate the effectiveness of Power Cards in teaching social skills to children with ASD in some aspects. First, it remains unclear if target skills will maintain after the intervention is faded given that fading was performed in only one study

[Daubert]. Second, further research is needed to demonstrate if acquired skills can maintain and generalize across different conditions

[Rose, 2020]. Although there is no consensus on a theoretical or empirical framework regarding when to measure maintenance after the behavior change is consistent, previous research suggested measuring it 2 to 8 weeks after the withdrawal of intervention. Third, although the intervention was conducted in typical settings (e.g., school) by typical agents in most of the previous studies

[Olçay], there are no studies in which the intervention agent developed and then implemented Power Cards with individuals with ASD. In other words, no studies investigated the effectiveness of training intervention agents in implementing Power Cards, as such further research is needed to demonstrate if typical agents can develop and implement the procedure for individuals with ASD.

It is significant for teachers to implement effective interventions to provide their students with effective educational services. This raises the need for in-service professional development (PD). Using effective treatments for individuals with ASD in general and special education classrooms contributes to achieving major principles of special education

[Atas; Travers] and improves research to practice gap

[Cook; Odom]. One way to achieve this is through PD that can be delivered in person, through telehealth, in groups, or individually

[Brooker Lozott, 2021]. The PD literature suggests that the trainings should include at least two components of behavioral skills training (i.e., instructions, feedback, rehearsal, and modeling) and that providing ongoing support for teachers can yield positive outcomes in the maintenance of acquired skills

[Suhrheinrich]. Therefore, behavioral skills training (BST) and coaching offer the promise for PD, thus facilitating the use of effective treatments in educational settings

[Kretlow; Miltenberger]. In this regard, there is a need for further PD research that uses BST and coaching

[Darling-Hammond, 2009]. Previous research revealed that PD trainings performed on-site or remotely showed no differences in terms of effectiveness

[Hay-Hansson; Vismara]. However, remote training is an alternative option to face-to-face training since it eliminates travel time and associated costs, as well as allowing for more flexible time for scheduling

[Lerman; Vismara]. Additionally, the necessity of and demand for remote training have increased due to COVID-19 pandemic

[Saral].

Taking all together, the literature on effective instruction revealed that additional research is needed to investigate the effectiveness of Power Card procedure for individuals with ASD in terms of acquisition, maintenance, and generalization to enhance the empirical evidence-base for this procedure. Furthermore, the literature on professional development and coaching revealed that further research should investigate the effects of remote BST and coaching of professionals to use effective treatments accurately. Therefore, we investigated whether (a) remote BST and coaching were effective in teaching how to develop and implement Power Cards to teachers of students with ASD, and (b) Power Card procedure was effective in teaching social skills to students with ASD. The following research questions guided the study: (1) Will remote PD through BST and coaching be effective in developing and implementing Power Cards by teachers in teaching social skills to their students with ASD? (2) Will teachers maintain developing and implementing Power Cards after two and four weeks? (3) Will teachers generalize developing and implementing Power Cards across different students, settings, and target behaviors? (4) Will Power Cards be effective in teaching social skills to students with ASD? (5) Will students with ASD maintain the acquired skills after 2 and 4 weeks? (6) Will students with ASD generalize the acquired skills across different settings and teachers? (7) What are the opinions of the teachers about the study?

Method

Participants

Three psychologists (They are referred as “teachers” throughout the article.) acting as a special education teacher and their students with ASD from a foundation school participated in the study (Mrs. Selcen with Ozan, Ms. Deniz with Sercem, and Mrs. Gulsah with Mehmet). Prior to the study, the teachers had indicated that they needed support for expanding their knowledge and skills in practices to teach social skills to their students with ASD. Thus, the current study aimed at meeting these demands indicated by the teachers. Written and verbal information about the study was given to all teachers by the researchers. The researchers also asked the teachers to give written and verbal information about the study to the parents of all students in the school to identify voluntary parents. Written consent for participation was obtained from all teachers and the voluntary parents of the students.

Teachers

Three female psychologists working as a special education teaches – Mrs. Selcen (aged 32), Ms. Deniz (aged 34), and Mrs. Gulsah (aged 37) – participated in the study. All teachers were working in the special education school that the student participants attended. The special education school provided 30–40 hours of individual and group special education services to students diagnosed with ASD and aged between 3 and 12. All teachers held a bachelor’s and master’s degrees in psychology. The teachers had 8, 11, and 13 years of experience implementing behavior analytic interventions (i.e., scripting, video modeling, and prompting) to students with ASD respectively. However, they had no educational, theoretical, or practical background for implementing story-based interventions. The prerequisite for participation was that all teachers should be voluntary to participate in the study for at least three days a week. Additionally, the teachers were required to have digital literacy skills in turning on computer, joining and starting video meetings, sharing screen, changing video and mic settings, and recording and sending videos through smartphones. This was evaluated by scheduling a meeting on Zoom, a video conferencing software.

Students with ASD

Three male students aged between seven and 12 participated in the study (see Table 1). All children were diagnosed with ASD based on the psychiatrist’s opinion and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) criteria. Ozan was an eight-year-old and a second-grade male student. Sercem was seven years old male student who attended first-grade classroom. Mehmet was a 12-year-old male student. He attended sixth grade. The researchers used the checklist in Social Skills Curriculum for Training Students with ASD used in Turkey to assess participating students’ social skills

[Ministry of National, 2018]. Based on the checklist, Ozan could follow simple directions, respond to questions, use full sentences comprised of two or more words to greet someone, request and initiate social interactions. Furthermore, he could make eye contact during a conversation. However, he had difficulty in emitting courtesy words and adaptive social skills (e.g., collaboration with peers). Sercem could follow simple directions, use sentences comprised of two or three words to request and respond to questions. He had difficulty in emitting courtesy words, maintaining conversations appropriate to the context, and exhibiting adaptive social skills. Lastly, Mehmet could follow directions, respond to questions, and use full sentences comprised of three or more words to request and initiate social interactions. He had difficulty in emitting courtesy words, maintaining conversations appropriate to the context. All students did not use any verbal or non-verbal responses that showed appreciation. They also did not know how to read and write.

Table 1

Characteristics of Student Participants

|

Name

|

Age

|

Gender

|

Grade

|

Diagnosis

|

|

Ozan

|

8

|

Male

|

Second grade

|

ASD

|

|

Sercem

|

7

|

Male

|

First grade

|

ASD

|

|

Mehmet

|

12

|

Male

|

Sixth grade

|

ASD

|

The following prerequisite skills were identified for the students as being able to (a) perform simple vocal instructions and (b) comprehend a story that comprises of 10–15 sentences of max five words. The teachers instructed their students to give objects or sit in a chair to determine that they could perform simple vocal instructions. The criterion was five correct responses out of five trials for one session. The teachers also read a story of between 10–15 sentences of four or five words to their students, then asked them wh-questions (i.e., what, where, who, and how) about the story to evaluate the second prerequisite skill. The criterion was giving correct responses to all wh-questions for one session.

Implementer, Observer and Experts

Both researchers who were experienced with developing and implementing Power Cards remotely provided BST and coaching for the teachers. The first researcher had a PhD degree in special education and the other was a doctoral student in the same field. They had 16 and 6 years of experience working with and teaching social skills to students with ASD respectively. Another doctoral student in special education participated in the study as an independent observer. The observer collected the interobserver agreement and procedural fidelity data. The second researcher explained and modeled the observer regarding how to collect reliability data. Four academic experts in the field of special education provided their opinions for the study. First, two experts who were experienced with Power Cards reviewed and evaluated the scripts and Power Cards prepared by participating teachers for their students. In evaluating the scripts and Power Cards, they used the checklist provided in Table 2. Second, another two experts who were experienced with single-case and qualitative research provided their opinions for social validity question form.

Table 2

Steps for Developing Scripts and Power Cards

|

Step 1. Script Development

|

|

1. Describes the context that is troubling for the student to exhibit the appropriate behavior

|

|

2. Writes a rationale for why the hero should exhibit the appropriate behavior in the given context

|

|

3. Describes the appropriate behavior exhibited by the hero with brief and simple sentences (max. 5)

|

|

4. Writes a note of encouragement for the student to try the new behavior

|

|

5. Uses a visual graphic of the hero

|

|

Step 2. Power Card Development

|

|

6. Writes a rationale for why the hero should exhibit the appropriate behavior in the given context

|

|

7. Describes the appropriate behavior exhibited by the hero with brief and simple sentences (max. 5)

|

|

8. Writes a note of encouragement for the student to try the new behavior

|

|

9. Uses a visual graphic of the hero

|

Setting and Materials

Due to COVID-19 pandemic, all PD sessions were delivered remotely, from January 2021 to May 2021. The researchers developed a Likert-type Video Conferencing Software Preference Assessment Form that included 10 softwares (e.g., FaceTime, Zoom) for the teachers. The teachers then indicated the most preferred video conferencing software by scoring each one between 1 and 5. Zoom was indicated as the most preferred software by the teachers. Furthermore, coaching support was individually delivered to teachers through phone calls. In the PD sessions, which were also conducted individually, the researchers used PowerPoint slide presentations, a correct video example of developing scripts and Power Cards, and correct and incorrect video examples of implementation of the procedure as well as a computer and headphones.

The implementation of Power Cards occurred in each student’s classroom. The sessions were conducted 1:1 format as no group sessions were performed at the school due to COVID-19 pandemic. Generalization sessions were carried out in a different classroom than the intervention setting. The teachers used a variety of materials (e.g., iPad, a disinfectant bottle cap, and a bar of chocolate) in each trial during the experimental sessions to promote generalization. Additionally, each student had one script and Power Card during the intervention sessions. To develop a personalized script and Power Card for the students, the teachers first determined their student’s high interest areas through a combination of direct observation and parent interview before developing individualized scripts and Power Cards. For this study, high interest was defined as any source of special interest such as a person, a character, or an object. Based on the interviews and observations, cartoon hero figures were determined as the special interest figures of the students. The scripts were A4 size and Power Cards were 5×10 cm laminated white papers that included the picture of the hero and the text. Finally, the teachers used their smartphones to video record the sessions.

Experimental Design

A one-group pre-test/post-test design was used to evaluate the effects of PD on the teachers’ performance on script and power card development and implementation [Akbay, 2019]. Furthermore, a multiple probe design across students was used to examine the effects of teacher-implemented Power Cards in teaching social skills to the students with ASD. Experimental control was established when the dependent variable increased only after the independent variable was presented in a time-lagged manner [Gast, 2014].

Dependent and Independent Variables

There were three dependent variables in the study. The target behaviors for the teachers were the ability to (1) develop scripts and power cards and (2) implement the Power Cards procedure. Teachers’ performance on developing the scripts and Power Cards was evaluated using a checklist (see Table 2) as described by Campbell and Tincani

[Campbell]. As to the implementation of the procedure, the researchers evaluated teachers’ performance using the task analysis provided in Intervention Sessions column in Table 3. As all teachers were already experienced with conducting probe sessions, this was not set as a dependent variable. However, their performance on conducting daily probes was evaluated using task analysis in Daily Probes, Maintenance, and Generalization Sessions column in Table 3. The researchers used a plus (+) to indicate that the teachers performed a step correctly, and a minus (-) to indicate that the teachers delivered a step incorrectly or failed to perform a step. The researchers used the following quotient to calculate the percentage of accuracy: dividing the number of correct steps by the number of correct and incorrect steps and multiplying by 100. There were 14 evaluations for daily probe and intervention sessions for Mrs. Selcen, 15 for Ms. Deniz, and seven for Mrs. Gulsah. Furthermore, there were two evaluations for each maintenance and generalization sessions across all teachers.

Table 3

Teacher Behaviors in Experimental Sessions

|

Intervention Sessions

|

Daily Probe, Maintenance, and Generalization Sessions

|

|

1. Secures the student’s attention

|

1. Directs the student to activity

|

|

2. Reads the script and Power Card to the student

|

2. Delivers appropriate behavioral consequences

·Presents natural reinforcement for correct responses

·Ignores incorrect or no responses

|

|

3. Asks three wh-questions related to the text

|

|

|

4. Waits five-second response interval

|

|

5. Delivers appropriate behavioral consequences

·Reinforces correct responses

·Reads the corresponding sentence for incorrect or no responses

|

|

6. Places the Power Card next to the student

|

|

7. Directs the student to activity

|

|

8. Delivers appropriate behavioral consequences

·Presents natural reinforcement for correct responses

·Reads the Power Card for incorrect or no responses

|

|

9. Provides praise for cooperation at the end of the session

|

The dependent variable for the students was their acquisition of the target social behaviors. The researchers first used the checklist in the Social Skills Curriculum for Training Students with ASD to determine dependent variables for the students. Next, they collaborated with the teachers of the students to select the target behaviors considering students’ Individualized Education Program (IEP), then asked the parents of the students to use the IEPs and checklist to identify the behaviors that their child needed. Based on the results of the checklist, students’ IEP, and parental opinions, the dependent variable was determined as emitting courtesy words for the students. Identifying the dependent variable, the researchers then asked the teachers and parents to state which courtesy word they preferred for the participants with ASD. The courtesy word was determined as thanking for all students. As thanking behavior can occur across different contexts, the researchers again interviewed the teachers and parents of the participants with ASD regarding the context of thanking behavior. As a result, the context was determined as thanking for help for Ozan, thanking for a gift for Sercem, and thanking upon accessing the requested item for Mehmet. Thanking was operationally defined as saying “Thank you.” or using an instance of polite expression for thanking (i.e., “Thanks.”) within 5 seconds of the event. Each dependent variable was recorded using event sampling. There was a total of four trials in each intervention session, and the criterion for the target behaviors for each student was 100% correct responding across three consecutive daily probe sessions. The teachers used a plus (+) to indicate that the student performed the behavior correctly, and a minus (-) to indicate that the student exhibited the behavior incorrectly or failed to exhibit the behavior. The teachers used the following quotient to calculate the percentage of correct responding: dividing the number of correct responding by four and multiplying by 100. There were 14 evaluations for daily probe and intervention sessions for Ozan, 15 for Sercem, and seven for Mehmet. Furthermore, there were two evaluations for each maintenance and generalization sessions across all students.

There were two independent variables in the study. The independent variable for teachers was remote BST and coaching. The researchers developed and used the task analysis regarding the delivery of BST and coaching (see Table 4). The other independent variable of the study was the Power Card procedure delivered by the teachers. The researchers collected data on the teachers’ behaviors using the task analysis in Intervention Sessions column in Table 3.

Table 4

Researchers Behaviors during Behavioral Skills Training and Coaching

|

Behavioral Skills Training

|

Coaching

|

|

1. Gives instructions from PowerPoint slide presentations

|

1. Conducts a general evaluation regarding teacher’s performance

|

|

2. Does modeling through video-modeling

·Modeling correct steps of implementation

·Modeling incorrect steps of implementation*

|

2. Reinforces correct responses

|

|

3. Performs role-playing

|

3. Presents positive and corrective feedback for incorrect responses

|

|

4. Gives feedback

·Reinforces correct responses

·Presents positive and corrective feedback for incorrect responses

|

4. Provides praise for cooperation at the end of the session

|

|

5. Provides praise for cooperation at the end of the session

|

|

Note. * – conducted only in Professional Development for Scripts and Power Cards Implementation session.

General Procedure

PD consisted of a total of two sessions for training teachers to develop and implement scripts and Power Cards: Professional Development for Scripts and Power Cards Development session and Professional Development for Scripts and Power Cards Implementation session. Each session was conducted in different days. The purpose of the first session was to train teachers to develop scripts and Power Cards. In the second session, the researchers prepared teachers to implement the Power Cards procedure.

Professional Development for Scripts and Power Cards Development

In the first session, remote BST regarding developing scripts and Power Cards was individually delivered on Zoom platform. Before the training, the researchers conducted a pre-test session to assess the teachers’ performance on developing scripts and Power Cards. As the teachers had no background regarding story-based interventions, the researchers briefly make an explanation of the procedure to make the instruction meaningful: “Power Cards procedure is a story-based intervention that includes a script and a power card to teach a skill to students. Script is a story-like text and power card is a small card that includes the summary of the script.” Next, the researchers asked the teachers to prepare a script and a Power Card about a social skill (i.e., asking for help). All teachers demonstrated 0% accuracy during the pre-test session. After the pre-test session, the researchers initiated the training on scripts and Power Cards development.

During the training, the researchers provided PD on the description of Power Card procedure by delivering BST. The delivery of BST involved the researchers first providing the teachers with verbal and written instructions outlining the relevant information of the Power Card procedure. In fact, the researchers used a PowerPoint presentation that included social skill impairments in ASD, definition and advantages of story-based interventions, overview of Power Card, and preparing scripts and Power Cards. Following the instruction step, the researchers provided modeling through a researcher-made video sample of developing scripts and Power Cards by using Zoom’s screen-share function. In this 9-minute video, one of the researchers prepared a script and a Power Card about asking for help on Microsoft Word, simultaneously explaining the steps in Table 2 and highlighting the relevant sentences (e.g., “As you can see in the sentence I’ve highlighted with yellow, I’ve described the appropriate behavior exhibited by the hero.”) In the following step of BST, the researchers provided teachers with an opportunity to rehearse the steps by saying, “Please prepare a script and a Power Card for a social skill that you choose.” After the teachers prepared the script and Power Card, they sent them to the researchers via Zoom’s chat function. The researchers evaluated them and provided the teachers with performance feedback in the form of an instruction (i.e., “It is good that you’ve described the hero’s appropriate behavior but remember that you should use simple sentences instead of long ones.”) The researchers provided praise for cooperation at the end of the training and conducted a post-test session.

In the post-test session, the researchers asked the teachers to develop a script and a Power Card about the social skill in the pre-test. All teachers demonstrated 100% accuracy during the post-test session. Thus, the researchers concluded the first session of PD. The training session lasted 50–55 min across teachers. In the pre- and post-test sessions, teachers’ performance on developing the scripts and Power Cards was evaluated with Table 2 using the following quotient: dividing the number of correct steps by the number of correct and incorrect steps and multiplying by 100.

When the remote PD for Scripts and Power Cards Development was concluded, the researchers gave the teachers an assignment to develop a script and a Power Card to teach the behavior targeted for their student. Next day, the teachers e-mailed the scripts and Power Cards to the researchers for evaluation. None of the teachers could accurately state the rationale for why the hero should exhibit the target behavior in the scripts and Power Cards, which resulted in 88.89% accuracy. Thus, the researchers provided coaching support through phone calls. All teachers edited their Power Cards following the coaching support, then e-mailed them to the researchers again. After one coaching session, all teachers could develop the scripts and Power Cards with 100% accuracy. As these scripts and Power Cards were to be used during the Intervention, the researchers sent the scripts and Power Cards to two academic experts in the field of special education for expert review. The experts indicated that the scripts and Power Cards were developed at 100% accuracy according to the steps in Table 2. The researchers sent the scripts and Power Cards to the teachers and the second PD session was initiated.

Professional Development for Scripts and Power Cards Implementation

The purpose of the second PD session was to train teachers to implement scripts and Power Cards. This session was conducted individually for all teachers on Zoom platform before and after the training as pre- and post-test.

In this session, remote BST regarding implementing scripts and Power Cards was individually delivered on Zoom platform. Before the training, the researchers conducted a pre-test session to evaluate the teachers’ performance on implementing scripts and Power Cards. During the pre-test, the researchers asked the teachers to implement the procedure by using the script and Power Card that they prepared for their student during the Professional Development for Scripts and Power Cards Development. The teachers were asked to make implementation to one of the researchers who role-played a student. All teachers demonstrated 0% accuracy during the pre-test session. After the pre-test session, the researchers initiated the training on scripts and Power Cards implementation. During the training, remote BST regarding implementing scripts and Power Cards was individually delivered on Zoom platform. As to remote BST, the researchers conducted one session for the teachers individually in a time-lagged manner (see Table 4). In the first step of BST, the researchers first described how to implement Power Cards through a PowerPoint presentation that included implementation steps and a flowchart of Power Cards, fading the Power Cards, and important points in the implementation. Following the instruction step, the researchers modeled how to implement the procedure through a 5-minute correct video example in which the interventionist implemented the procedure to a student with ASD following the intervention steps in Table 3. The teachers also watched a 4-minute incorrect video example in which the interventionist implemented the procedure with low accuracy to draw teachers’ attention to potential implementation errors (e.g., not asking wh-questions related to the text and delivering appropriate behavioral consequences). Both videos included captions for each step of implementation to enhance comprehension of and attention to the video. After viewing the videos, the teachers were asked to rehearse to implement the procedure to one of the researchers who role-played a student. During the role-playing, the researchers provided feedback to the teachers on their performance. They identified instances in which the teachers did or did not exhibit the correct step. Correct steps resulted in praise (e.g., “It’s perfect that you’ve secured the student’s attention!”), while the researchers provided feedback in the form of an instruction for incorrect steps (e.g., “You should provide praise for cooperation at the end of the session.”) The researchers provided praise for cooperation at the end of the training and conducted a post-test session.

In the post-test session, the researchers asked the teachers to implement the procedure to one of the researchers who role-played a student. All teachers could implement the script and Power Card with 100% accuracy. Thus, the researchers concluded the training. The session lasted 50–55 minutes across teachers. In the pre- and post-test sessions, teachers’ performance on implementing the scripts and Power Cards was evaluated based on the task analysis provided in Intervention Sessions column in Table 3 using the following quotient: dividing the number of correct steps by the number of correct and incorrect steps and multiplying by 100. After a 10-minute break, the researchers assessed teachers’ ability to conduct daily probe sessions during role-playing although they had indicated they were experienced with conducting daily probes. This assessment session lasted around 10 minutes across all teachers. The researchers determined that all teachers could conduct daily probe sessions by following the steps in Table 3. Thus, they did not deliver the teachers PD regarding how to conduct daily probe sessions.

Coaching Sessions

Following the PD sessions, the teachers implemented the Power Card procedure with the participating students. They video recorded each intervention session, then sent them to the researchers via Telegram, a messaging app. The researchers viewed the videos and assessed teachers’ accuracy of implementation. The researchers delivered all feedback through phone calls when teachers’ performance of implementing the procedure was below 100%. During coaching, the researchers delivered the teachers positive feedback for correct steps (e.g., “Mrs. Selcen, you perfectly secured your student’s attention at the beginning of the session.”), and corrective feedback for incorrect steps (e.g., “Mrs. Selcen, please end the session with a positive and motivating statement.”). The steps for delivering feedback are presented in Coaching column in Table 4.

Baseline Sessions

Controlled baseline sessions were conducted during ongoing classroom activities to assess students’ pre-intervention performance on target behaviors. As to the target behavior of thanking for help, the teacher arranged the environment to ensure that tasks were difficult for Ozan (e.g., opening a tight disinfectant bottle cap, unlocking a locked iPad). Then, she helped him and assessed whether the student exhibited the correct response. There was a total of four trials in each session with different tasks. As to thanking for a gift, Ms. Deniz gave a gift to Sercem while saying, “Surprise!” or “I’ve a gift for you!” Ms. Deniz assessed whether the student exhibited the correct response. There was a total of four trials in each session with different gifts. As to thanking upon accessing the requested item, Mrs. Gulsah arranged the environment to ensure that one of the items in a context was missing (e.g., a missing crayon or a piece of puzzle). Then, she gave the item upon Mehmet’s request and assessed whether he exhibited the correct response. There was a total of four trials in each session with different contexts. The teachers naturally reinforced the correct responses by excitedly saying, “You’re welcome!” and they ignored incorrect and no responses before providing the next trial.

Intervention Sessions

These sessions were conducted in each student’s classroom. The teachers implemented Power Card procedure for one session three days per week. The teacher first secured the student’s attention (i.e., “I’ve got a beautiful story for you. Ready?”) and verbally reinforced his affirmative responses (i.e., “Perfect. Let’s get started!”). The teacher read the script and then the Power Card to the student. Next, she asked the student wh-questions related to the story (i.e., “What does Batman say when his teacher helps him?”) and waited five seconds for a response. Correct responses resulted in verbal reinforcement. The teacher read the corresponding sentence in the Power Card following incorrect or no responses. After asking a total of three wh-questions, the teacher placed the Power Card next to the student and directed him to the naturally occurring classroom activities in which he could exhibit the target behavior (e.g., playing with locked iPad or opening disinfectant bottle cap to sanitize hands), and waited 5-second response interval. The teacher naturally reinforced the correct responses by excitedly saying, “You’re welcome!” For incorrect and no responses, the teacher reread the Power Card maximum three times per incorrect or no response. Finally, the teachers provided their student with praise for cooperation at the end of each intervention session. Each session lasted between 8 and 12 minutes across students. The teachers continued implementation until their students reached the mastery criterion. The criterion was 100% correct responses for all students for three consecutive daily probes.

Daily Probe Sessions

The teachers conducted daily probes before each intervention session during ongoing classroom activities to assess acquisition of the target behaviors by the students. Daily probes were the same as baseline sessions. In fact, the scripts and Power Cards were withdrawn in these sessions. There was a total of four trials in each daily probe in which the teachers created a situation that allowed the students to exhibit the target behavior.

In conducting these sessions, the teachers followed the steps provided in Daily Probes, Maintenance, and Generalization Sessions column in Table 3. Although conducting daily probes was not a dependent variable, the researchers collected data on teachers’ behaviors to determine whether it was necessary to deliver coaching. Yet, there was no need to deliver coaching regarding any steps of daily probe sessions as all teachers conducted these sessions with 100% accuracy.

Fading Sessions

The purpose of the fading sessions was to promote transfer of stimulus control, as well as facilitating the maintenance of acquired skills. After each student met the mastery criteria, the script was withdrawn, and the Power Card was faded to a card with the student’s favorite hero and three steps corresponding with the target behavior. Furthermore, the students carried the card in an ID badge holder with neck strap so that the card was out of view. These sessions were conducted until the students exhibited 100% correct responding across three consecutive fading sessions.

Maintenance Sessions

The maintenance sessions were carried out 2 and 4 weeks for teachers and students after the intervention sessions ended. In these sessions, the teachers respectively conducted one daily probe during ongoing classroom activities and one teaching session by following the steps in Table 3. They also collected maintenance data on the target behaviors for their students. Thus, the researchers could collect maintenance data on both teachers’ and students’ performances. Maintenance sessions were the same as daily probes.

Generalization Sessions

The generalization sessions were conducted before and after the intervention as pre- and post-test across students, settings, and target behaviors for teachers, and across settings and teachers for students. A different student from the study participants took part in the generalization sessions for teachers. Each teacher first reviewed the student’s IEP and determined a different target skill (i.e., turn-taking during an activity) from the study dependent variables. Then, they developed a script and Power Card for the student. The teachers conducted one intervention session with the target student in a different classroom than the intervention setting. The researchers assessed teachers’ performance on developing the script and Power Card with Table 2, and implementation accuracy with Table 3.

The generalization sessions for students across settings and teachers were performed during ongoing classroom activities before and after the intervention as pre- and post-test. A different teacher conducted these sessions in a different classroom at school. These sessions were the same as daily probes. As mentioned before, no group sessions were performed at the school due to COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, generalization across peers could not be measured for the students.

Interobserver Agreement and Procedural Fidelity

For interobserver agreement (IOA) analyses for students, the second researcher and a doctoral student who was blind to the study purposes and conditions of the video clips independently recorded all students’ responses for 30% of the sessions per condition across each student. IOA percentages were calculated using a point-by-point agreement formula

[Ledford, 2018]. The mean IOA was 100%.

Two types of procedural fidelity (PF) data were assessed. First, an independent observer watched 100% of the video records of remote PD sessions and listened to 30% of coaching sessions. PF data was calculated with the following quotient: the number of observed researcher behaviors divided by the number of preplanned researcher behavior and multiplied by 100. The PF data was 100% for remote BST and coaching. Additionally, the second researcher collected PF data for all sessions because it was planned to deliver coaching support when teachers’ performance on implementing Power Cards decreased below 100%. The PF data was calculated using the following quotient: the number of observed teacher behaviors/ the number of preplanned teacher behaviors × 100

[Ledford, 2018]. For intervention, the mean PF was 96.97% (77.78% for the first session, 88.89% for the second session, and 100% for the rest of the sessions) for Mrs. Selcen, and 97.22% (88.89 for the first session and 100% for the rest of the sessions) for Mrs. Gulsah, and it was 100% for Ms. Deniz. The PF was 100% for all baseline, daily probe, and maintenance, and generalization sessions. Also, an independent observer collected PF data for 100% of the video record across all conditions. PF data collected by the second researcher and the independent observer showed 100% consistency.

Social Validity

The researchers developed a social validity question form that included 9 open-ended questions. The social validity questions were (a) Do you think learning Power Card method was important to you? Why? Why not? (b) What do you think about the use of Power Card in teaching social skills to your student with ASD? (c) Do you think whether to use Power Card for teaching different skills to your other students with ASD in future? (d) What did you like most about the Power Card? (e) What did you like least about the Power Card? (f) What are your opinions regarding remote coaching and professional development procedure? (g) What did you like most about remote coaching and professional development procedure? (h) What did you like least about remote coaching and professional development procedure? (i) What do you think about the use of remote coaching and professional development procedure to teach general and special education teachers how to implement a variety of procedures such as Power Card for their students with ASD? The second researcher remotely conducted semi-structured interviews with the teachers on the following: (a) feasibility of the Power Cards, (b) acceptability of remote BST and coaching, and (c) social significance of the target skills for the students. Social validity results were analyzed descriptively.

Results

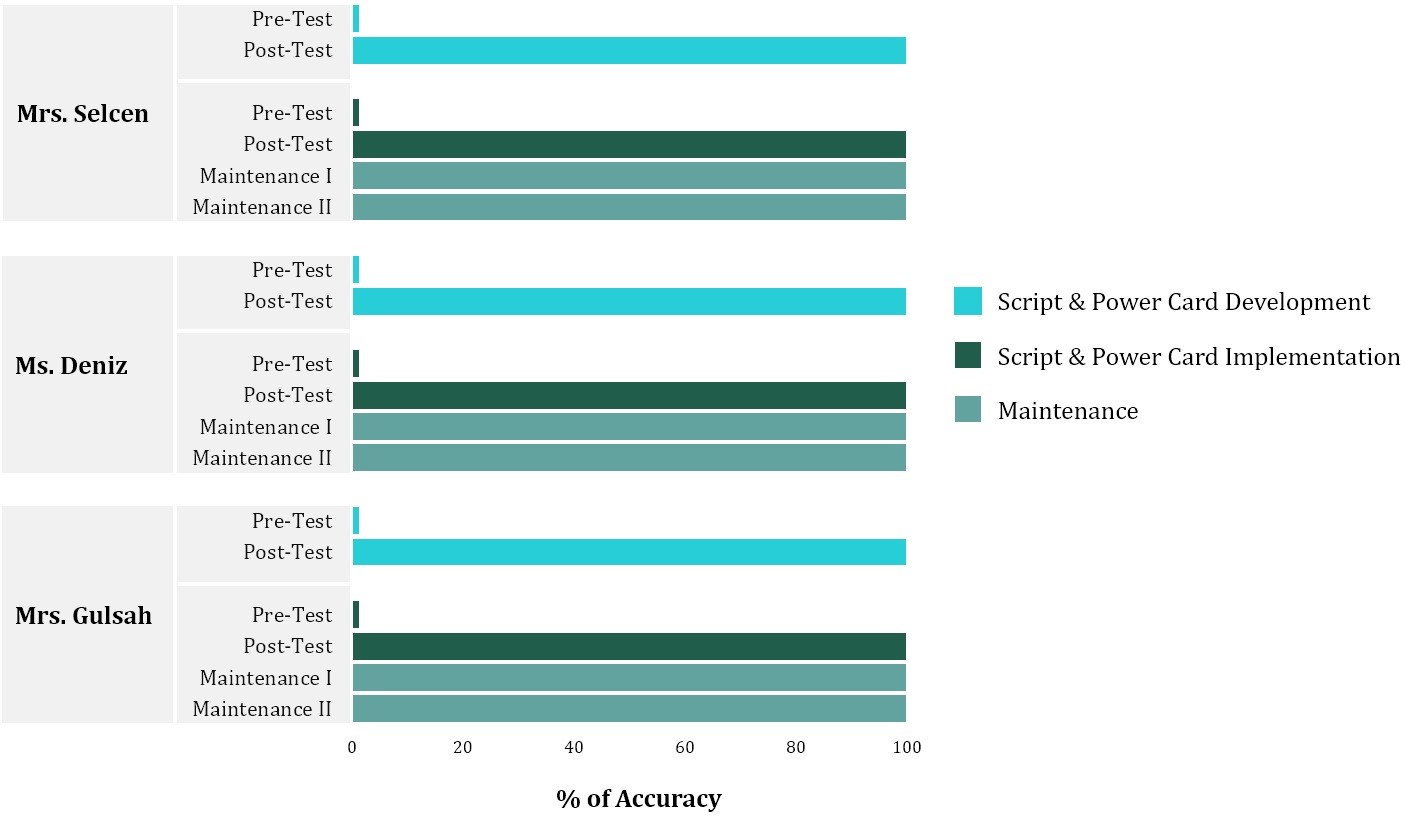

Effects of Professional Development

The teachers’ performances were evaluated before and after the Professional Development Training for Scripts and Power Cards Development and Implementation as pre- and post-test. Figure 1 indicates that the teachers demonstrated 0% accuracy in pre-test session and 100% in the post-test for scripts and Power Cards development and implementation.

After the PD sessions, the teachers started implementing the procedure to their students. During the intervention, the researchers delivered teachers coaching support at any point when their performance was below 100% in a session. Mrs. Selcen received coaching for implementing Power Cards for the initial two sessions, and Mrs. Gulsah for one session. Ms. Deniz’s accuracy of implementation was 100% across the intervention sessions, so she did not get any coaching support. All teachers maintained their accuracy of implementation at 100% during the maintenance sessions. Also, they did not perform any correct responses during the pre-test generalization session and demonstrated at 100% during the post-test.

Figure 1. The Percentages of Correct Responses of Teachers

during Professional Development Sessions

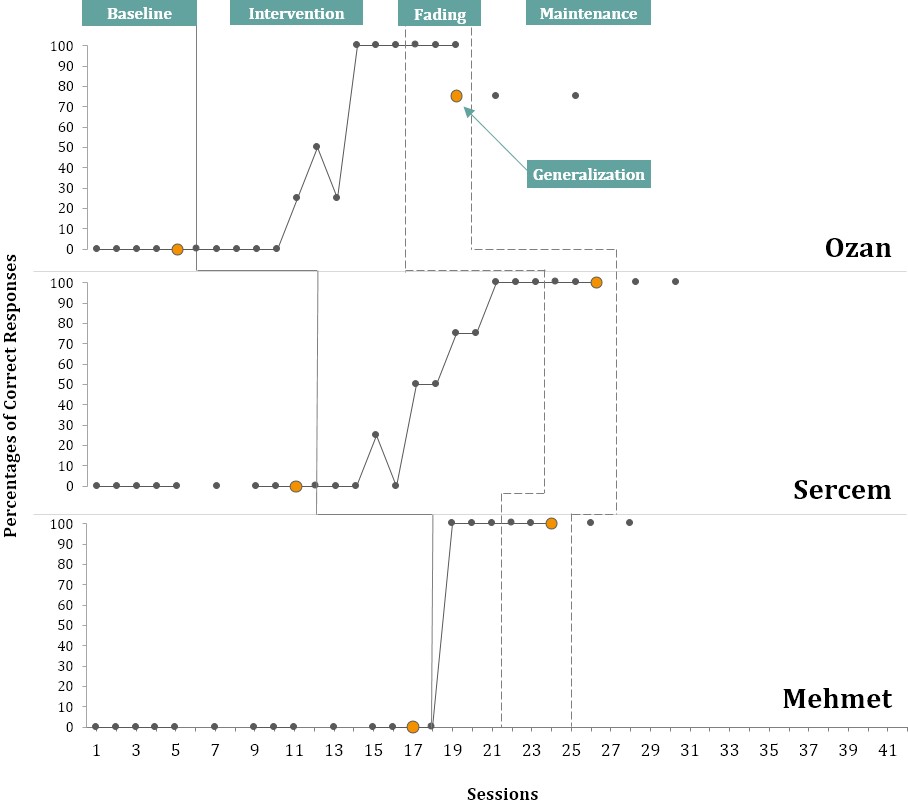

Effectiveness of Power Cards

In evaluating the effectiveness of Power Cards on students’ acquisition of target behaviors, the researchers plotted percentages of correct responses in daily probes.

As seen in Figure 2, all students did not exhibit any correct responses during baseline. With the introduction of Power Cards, Ozan’s target responses remained at 0% for five intervention sessions which was followed by an increasing trend and change in level. Ozan reached the criterion in the ninth session and maintained exhibiting the target behavior at 75% when the intervention was removed. He did not exhibit any correct responses during generalization pre-test session but had 75% accuracy during the post-test. The trend and level of Sercem’s correct responses changed after the third session following the intervention. He reached the criterion in 10th intervention session. With the introduction of the intervention, there was an immediate upward trend in Mehmet’s target behavior after the first intervention session. He reached the criterion in the second session. All students demonstrated 100% accuracy in fading condition. Furthermore, Sercem and Mehmet maintained the target behavior with 100% accuracy. They also did not perform any correct responses during generalization pre-test session but had 100% accuracy during the post-test.

Figure 2. The Percentages of Correct Responses of Students across Conditions

Social Validity

All teachers indicated that learning how to implement a novel procedure was significant for teaching their students with ASD. For example, Mrs. Gulsah stated that Power Card was effective and easy to implement, and it could be an alternative when direct and systematic prompting was not effective. She also stated learning such an alternative procedure contributed to her PD. Additionally, all teachers indicated that they would implement the procedure in teaching various social skills to other students with ASD. Mrs. Selcen mentioned the procedure was flexible to make adjustments. All teachers noted that the procedure was naturalistic and could be implemented in different communal settings. For example, Mrs. Selcen said, “Students can carry the Power Card with themselves everywhere such as shopping malls.”, Mr. Deniz, “It is very easy to implement.”, and Mrs. Gulsah, “The procedure requires reasoning and analysis. The cards can be presented in a naturalistic way. Also, it is a cost-effective practice and can be implemented anywhere.” All teachers reported no negative aspects of the procedure, but all indicated assessment of several prerequisite skills before implementation could be a limitation. They stated these prerequisite skills should be the ability of listening, sitting still, speaking, and answering wh-questions. Regarding remote BST and coaching, all stated receiving feedback, keeping in touch, and reaching out the researchers easily contributed to their fast acquisition of the procedure. The teachers indicated no negative aspects of remote coaching, but positive aspects included receiving instant feedback and being practical, time-effective, and more efficient than face-to-face meetings. All teachers agreed on the applicability of remote BST and coaching for general and special education teachers to learn new teaching practices. However, Mrs. Selcen and Mrs. Gulsah noted some prerequisite skills should be identified for teachers as having knowledge and ability to implement systematic instruction and applied behavior analytic procedures.

Discussion

The current study revealed that the remote BST and coaching were effective in preparing teachers to develop and implement Power Cards with high accuracy. Also, the Power Card procedure was effective in acquisition, maintenance, and generalization of the target social skills by the students with ASD. Finally, all teachers reported positive opinions regarding the study.

Teacher Outcomes

Philipsen et al.

[Philipsen] suggest using technology as a platform for PD. The existing literature is promising in that remote PD may be an effective, feasible, and even alternative to face-to-face training and coaching for professionals who deliver autism-specific training

[Johnsson]. Remote training and coaching have the potential to provide PD that is efficient in terms of time, cost, and resources. Experts who are experienced with remote BST and coaching indicated the importance of some components (e.g., incorrect video examples) for successful practices

[Saral]. In this study, the researchers used PowerPoint presentations, correct and incorrect video examples in instruction and modeling steps of BST respectively. This might contribute to the efficiency since all teachers learned how to develop Power Cards within one PD session and implemented the procedure with 100% accuracy after coaching feedback for several sessions. Furthermore, using such components and/or BST during the PD contributed to the instructional efficiency, which might have minimized the need for coaching by the teachers. This provides evidence that the teachers quickly acquired the target skills although they had no educational background for implementing story-based interventions. Regarding the effectiveness, on the other hand, previous research found that the success of remote training was closely subjected to consumer satisfaction

[Sinclaire]. The social validity results revealed that all teachers were satisfied mainly due to getting instant feedback, referring to remote coaching. As well as providing preliminary findings that coaching may contribute to success of remote training, this study also showed that PD could be facilitated via remote training and coaching.

Although the researchers planned to deliver teachers coaching support at any point when the fidelity was below 100%, less coaching support was required than anticipated. After the first couple of intervention sessions, all teachers used the steps of Power Card procedure with 100% fidelity. Previous researchers supported preschool teachers

[Tunc-Paftali], general education teachers

[Tekin-Iftar], preservice teachers

[McLeod], or certified teachers

[Coogle; Shepley]. Therefore, the findings of this study contribute to the literature of special education.

As to coaching support, the most frequently delivered corrective feedback was providing praise for cooperation at the end of the session followed by waiting the 5-second response interval. This result replicated those of previous study

[Tunc-Paftali], but they differed from Tekin-Iftar et al.

[Tekin-Iftar] who reported most of the feedback was about delivering an attentional cue. Thus, service providers who train and coach teachers should bear in mind that they should not assume psychologists working as a special education teacher can accurately implement procedures and that they are likely to require training and coaching on procedures to ensure procedures are implemented with high fidelity. Furthermore, previous research that reported the frequency of coaching delivered coaching at the end of each session

[McLeod; Shepley; Tunc-Paftali] or every two sessions

[Tekin-Iftar]. In the current study, we delivered coaching only when teachers’ performance of implementing the procedure was below 100%. In fact, teachers needed limited coaching which was in initial intervention sessions. This finding is encouraging and promising because coaching may not be delivered on an ongoing basis and may therefore be more ecologically and socially valid than continuous delivery of coaching, which warrants future research.

Because producing long-term effects and generalization of the skills without ongoing coaching or support are goals of an intervention, measurement of maintenance and generalization of acquired skills by teachers would be valuable. However, Neely et al.

[Neely] reviewed tele-practice studies and found that only a handful of studies measured maintenance and generalization of learned skills by teachers. Research also suggests that it is challenging for teachers to maintain and generalize newly acquired skills of implementing a procedure

[Coogle, a]. The studies that measured maintenance and generalization of teachers’ skills reported mixed results, with some teachers implementing procedures at lower rates than during coaching for maintenance [e.g., 29] and not meeting the criterion for generalization [e.g., 2]. There are also studies reporting positive outcomes for both maintenance and generalization. For example, Tekin-Iftar et al.

[Tekin-Iftar] and Tunc-Paftali and Tekin-Iftar

[Tunc-Paftali] reported all teachers maintained and generalized target skills across content. Overall, in this study, visual analysis shows evidence that all teachers maintained and generalized preparing materials and their use of the procedure across different conditions. Therefore, this literature base can best be described as limited owing to scarce number of studies and mixed results for some teachers. Given the importance of measurement of maintenance and generalization as an indicator of an intervention’s social validity and quality of study characteristics, future researchers interested in remote BST and coaching must conduct additional studies with a focus on maintenance and generalization of teachers’ skills.

Social validity is an associated construct that is highly valued in special education, and it is a critical component in determining whether a practice has evidence-base

[Ledford]. It should be noted that few studies investigated the social validity of Power Cards

[Angell; Campbell; Davis]. Overall, in the current study, the teachers reported that the goals were significant, and the procedure and outcomes were effective. In addition to implementation of the procedure under typical conditions (e.g., classroom), they also reported that the procedure was easy to use, time- and cost-effective, and they will continue using the procedure in the future. For example, as anecdotal data, one participating teacher shared with the researchers that she started teaching her colleagues how to develop and implement Power Cards after the study. Also, all teachers stated they continued to implement Power Cards when the intervention was concluded. These findings are significant for developing and expanding the literature in terms of social and ecological validity. Based on this, teachers and the other implementers can implement Power Cards the students with ASD as it is a strength-based time- and cost-effective intervention. Moreover, parents, siblings, or peers can be trained on implementing Power Cards for decreasing challenging or increasing desired skills in individuals with ASD.

Student Outcomes

The current study also contributes to the literature by examining the effects of Power Cards delivered by teachers across student participants. Although Gagnon

[Gagnon, 2001] described the procedure as appropriate for individuals with high-functioning autism or Asperger syndrome, it was effective for participating students diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. These results are consistent with those of other studies that included participants with ASD [e.g., 12; 21]. It should also be noted that the ability to answer wh-questions is highly likely to be a critical prerequisite skill to participate in a Power Card procedure. Although no studies on Power Cards reported this as a prerequisite skill

[Olçay], this was validated in the social validity component of the current study. All participating teachers emphasized that the ability to answer wh-questions should be the first prerequisite skill to consider in addition to sitting still and maintaining attention before implementing Power Cards.

All students maintained exhibiting the target skills. Only two studies, aiming to teach social skills with Power Cards, measured maintenance

[Daubert; Spencer], and demonstrated short-term maintenance (max. 11 days) of learning positive outcomes. In this study, setting criterion as 100% in intervention conditions and fading Power Cards could have facilitated short- and long-term maintenance of the target social skills. Additional replications with a focus on maintenance of skills are needed.

Studies on Power Cards measuring generalization of target skills are still limited. For example, Davis et al.

[Davis] measured generalization across settings and people and Keeling et al.

[Keeling] across settings. Campbell and Tincani

[Campbell] highlighted the importance of measuring generalization of target skills acquired through Power Cards. In this study, the students generalized the acquired skills across different settings and teachers, which extends the literature in terms of measuring generalization across settings and people.

In this study, we systematically determined students’ socially valid special interests through a combination of teacher interviews and a checklist. First, we informally interviewed teachers, then asked them to send checklist to parents to determine the degree of heroes or sources of high interest. Research and The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) support incorporation of special interests into teaching strategies while accounting for strengths and preferences

[Bross; Individuals with Disabilities, 2006]. If special interest areas are not recognized or supported, then they may become a source of exclusion

[Bross]. They are also found to be effective due to their motivating or reinforcing qualities

[Campbell]. Thus, recognizing a student’s special interests may be especially useful in educational settings. However, a literature search revealed a limited number of studies using special interests of individuals with ASD in teaching a target behavior [e.g., 36; 43]. Given the unique nature of the procedure, future research should systematically continue to examine the potential of student’s special interest areas to teach various skills instead of extinguishing them. Additional replication studies are also needed to document the effectiveness of strength-based nature of Power Cards (i.e., incorporating special interests) for children with ASD. Therefore, families and teachers of individuals with ASD, and professionals can use special-interest areas to enhance the effectiveness of the procedure they implement.

Regarding the evidence base, there are systematic review and meta-analysis studies examining the effectiveness of Power Cards

[Leaf; Rose, 2020]. Authors in both studies highlighted the scarcity of studies meeting acceptable rigor and the need of additional research to determine the effect of Power Cards. Furthermore, Leaf et al.

[Leaf] stated the procedure could not yet be considered as evidence-based since the studies reviewed did not meet the quality standards proposed by Horner et al. in 2005

[Horner]. According to Horner et al., documentation of an evidence-based practice requires multiple single-subject studies conducted by at least three different researchers across at least three geographical locations. Therefore, we think that the results of this study contribute to literature base to establish Power Cards as an evidence-based practice in accordance with Horner et al. criteria

[Horner].

Limitations and Perspectives of the Study

We aimed at teaching saying, “Thank you.” to the students with ASD, but the focus on this social skill was narrow (i.e., thanking for a gift). This was the major limitation of the study. Future researchers may focus on more complex and advanced social skills (i.e., teamwork, problem solving, or recognizing emotions) when teaching students with ASD using Power Cards. Secondly, only three teachers and three students participated in this study, as such the findings were limited by characteristics. Future replications are needed with additional participants with different characteristics.

Furthermore, the second researcher collected the social validity data through participant judgement, as such data collection was not anonymous. Using social validity measures that are less subject to bias such as normative comparisons or blind ratings may provide more valid evidence of which goals, procedures, and outcomes are socially acceptable. Finally, we could not collect social validity data from the student participants due to lockdown and as the students could not efficiently attend the interviews that were conducted via Zoom, which is another limitation.

In future studies, the effectiveness and efficiency of Power Cards may be compared to other story-based interventions (e.g., Social Stories™). Moreover, future studies may compare the effectiveness and efficiency of in-person to remote professional development training and coaching as well as ongoing to intermittent coaching.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of the study, psychologists who worked as a special education teacher and never took special education field-based courses could develop and implement Power Cards with high accuracy after taking remote BST and coaching. In fact, they needed limited coaching which was only in initial intervention sessions. Furthermore, the Power Card procedure was effective to teach target social skills to their students with ASD. The students also maintained the acquired skills after the intervention was terminated, as well as generalizing them across different conditions. The semi-structured interviews with the teachers indicated that the teachers reported positive opinions regarding feasibility of the Power Cards, acceptability of remote BST and coaching, and social significance of the target skills for their students.