Introduction

Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) is defined as excessive video gaming leading to loss of functionality [Peters, 2008]. IGD has been included in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as a condition requiring further investigation [American Psychiatric Association, 2013]. In the International Classification of Diseases-11 (ICD-11), the World Health Organization (WHO) also described problematic gaming under the umbrella term of gaming disorder [King, 2019]. Previous studies used non-standardized terms such as gaming addiction, gaming dependency, problematic video gaming, etc. to denote the same phenomenon [Charlton, 2007; Kuss, 2012; Rehbein, 2010]. However, IGD is the most accepted and relevant term [Griffiths, 2014]. Thus, the term IGD is used in the current study. Despite lack of consensus on the term, it is well known that excessive gaming disrupts work life, education, and social relationships as well as physical and psychological well-being [King, 2019; Király, 2014; Richard, 2020; Wartberg, 2019].

Prevalence of IGD varies around the world. In a meta-analysis examining 20 studies from 11 different countries, the prevalence of IGD was found to vary between 0.7% and 27.5% [Li, 2018]. In Turkiye, the prevalence of IGD was reported to be between 2.4% and 11.8% [Baysak, 2020; Evren, 2018]. Studies conducted both in Turkiye and in other countries showed that IGD is more prevalent in men than in women. IGD is also more prevalent in adolescents and young adults than in middle-aged people [Festl, 2013; Paulus, 2018].

The complex etiology of IGD has not been fully elucidated [Paulus, 2018]. Combination of genetic, neurobiological, social, cognitive, and developmental processes, and features associated with game genres contribute to the development of IGD [Billieux, 2015; Cai, 2016; Domahidi, 2014; Eichenbaum, 2015; Jiang, 2012; Kuss, 2012; Trepte, 2012]. Researchers have attempted to explain the etiology of IGD using different models [King, 2016; Mills, 2020; Paulus, 2018; Yu, 2021]. One such theoretical framework attempting to elucidate IGD from an addiction perspective is the Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution (I-PACE) model [Brand, 2019]. I-PACE is a process model which stipulates that addiction to specific Internet functions arises from an interaction between personal core characteristics (such as genetics, stress vulnerability, psychopathology, personality, social cognitions, and motives for using the Internet), subjective perceptions and affective and cognitive responses pertaining to Internet-related stimuli, as well as several mediators and moderators including coping, reduced executive control, and Internet-related cognitive biases [Brand, 2016].

Specific motivational theories may enhance our understanding of the development and maintenance of IGD. Previous studies utilized Self-Determination Theory (SDT) to determine both positive and negative effects of online gaming on well-being [Allen; Mills, 2018; Ryan, 2006a; Scerri, 2019; T’ng, 2022]. SDT is a psychological macro-theory developed by Deci and Ryan in order to explain personality and individual motivations underlying behaviors [Deci, 2000; Deci, 2012]. One of the mini theories of SDT, which was utilized in the gaming literature, is called the Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT) [Ryan, 1996]. BPNT posits that there are three universal psychological needs: autonomy (a sense of volition or willingness), competence (a need for challenge and feelings of effectance), and relatedness (feeling connected with others) [Deci, 2008; Ryan, 2006a]. Satisfaction of these needs are essential for well-being [Patrick, 2007; Reis, 2000; Ryan, 2010; Tang, 2020]. Thwarting of needs in real life may prompt people to turn to online video games to satisfy these needs. Various studies reported that low need satisfaction in real life is associated with both IGD and other technological addictions, including problematic smartphone use and social media addiction [Cudo, 2020; Edmunds, 2006; Gugliandolo, 2020; Neys, 2014]. Thus the main assumption of the current study is that low satisfaction of basic psychological needs is associated with IGD either directly or through mediators.

In the I-PACE model, motives for Internet use are among the core characteristics of the person which may create a predisposition to addiction. However, the model is not specific to IGD and does not include gaming motivations. Gaming motivations have been classified in different ways [Lafreniere M.-A, 2012; Lopez-Fernandez, 2021; Yee, 2006; Yee]. Yee’s tridimensional framework for gaming motivations encompass achievement (advancement and competition), social (socializing, relationship, and teamwork), and immersion (discovery, customization, and escapism) motivations [Yee, 2006; Yee]. However, this model was criticized for being specific to massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG) as well as abandoning the escape motivation, which is of clinical significance in terms of IGD and comorbid psychopathology [Backlund; Ballabio, 2017; Fazeli, 2020; Melodia, 2022; Wang H.-Y, 2022]. On the other hand, Demetrovics et al. [Demetrovics, 2011] postulated that gaming satisfied basic human needs such as having fun, relating to others during game interactions, and feeling competent due to in-game achievements; which are in line with SDT. Demetrovics et al. [Demetrovics, 2011] empirically classified seven dimensions of gaming motivations: escapism (avoiding real life problems and undesirable inner experiences), coping (coping with negative emotions), social (being with and playing with others), competition (competing with and defeating others in order to feel a sense of achievement), fantasy (trying new identities and behaviors in a fantasy world), recreation (enjoying the game), and skill development (improving concentration and coordination).

Previous research demonstrated that gaming motivations including escapism and immersion/fantasy contribute to IGD [Backlund; Richard, 2020; Wang H.-Y, 2022]. While some gaming motivations lead to IGD, others may not be problematic for game users [Ballabio, 2017; Chen, 2023]. Gaming motivations, escapism in particular, may mediate the association of low basic psychological need satisfaction to IGD. In one study, it was found that the escape, coping, social, competition, and skill development motivations mediated the relationship between IGD and basic psychological need satisfaction [T’ng, 2022]. Knowledge derived from empirical as well as theoretical research indicates that escape motivation, which means playing games in order to avoid real-life difficulties, is more strongly associated with IGD compared to other gaming motivations.

In the current study, it was hypothesized that low satisfaction of basic psychological needs is associated with IGD both directly and through escape motivation as mediator. Based on the literature, other significant risk factors for IGD, including psychopathologies and low self-esteem, may also be mediators. The I-PACE model postulates that psychopathologies including depression, anxiety, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) predispose one to addiction. Empirical studies proved that IGD is associated with depression [Bahrainian, 2014; Brunborg, 2014; Cudo, 2020; Edmunds, 2006; Liu, 2018]. Individuals with depression were reported to use video games as a maladaptive coping strategy [Plante, 2019]. In another study, escape coping mediated the relationship between IGD and depression [Loton, 2016]. As for self-esteem, research showed that lower levels is a risk factor for IGD [Kim H.-K, 2009; Ryan, 2006; Stetina, 2011]. Individuals with lower self-esteem tend to create game avatars that align with their ideal selves rather than their real selves, which in turn increases IGD risk [Beard, 2016; Bessière, 2007; Stetina, 2011]. Also, SDT suggests that the prolonged lack of satisfaction in basic psychological needs results in low self-esteem [Deci, 2012].

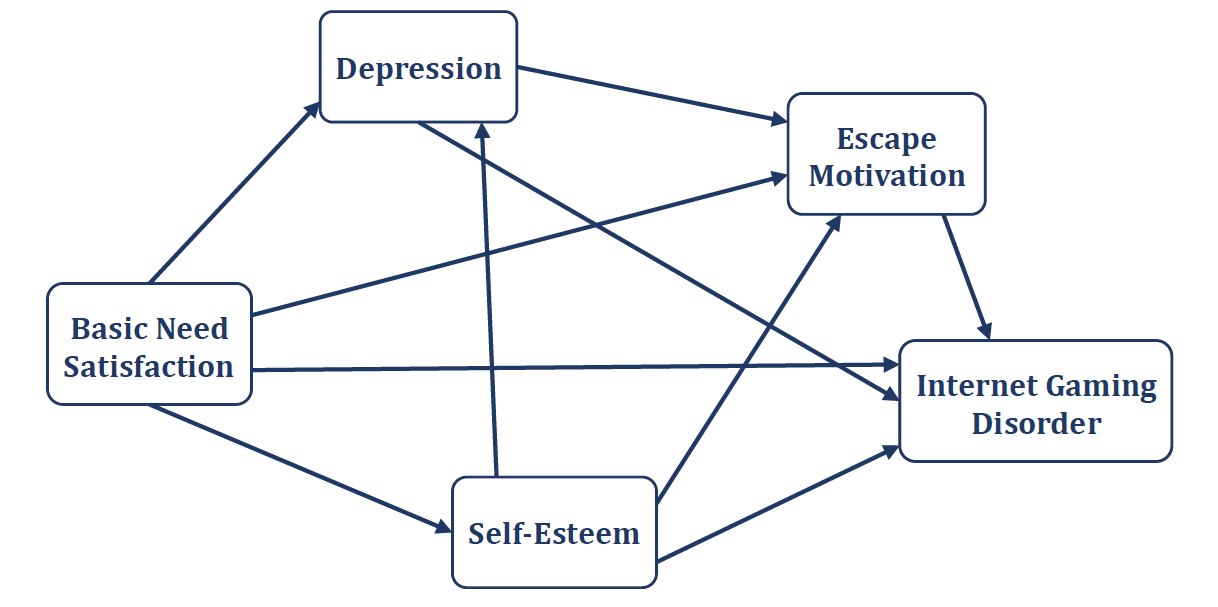

In sum, drawing insights from the SDT, the I-PACE model, and the gaming motivations literature, the current study sought to gain a better understanding of IGD. An integrative path model was developed in order to test the following hypotheses (see Fig. 1):

- Satisfaction of basic psychological needs is negatively associated with IGD.

- The association between inadequate satisfaction of needs and IGD is serially mediated by depression and escape motivation.

- The association between inadequate satisfaction of needs and IGD is mediated by self-esteem.

- The association between inadequate satisfaction of needs and IGD is serially mediated by self-esteem, depression, and escape motivation.

Fig. 1. Proposed integrative path model.

Method

Participants and Procedures

The current empirical study had a cross-sectional design. The purposive sampling method was used in order to recruit online video gamers. Prior to data collection, ethical permission to conduct the study was obtained from Izmir Katip Celebi University’s Board of Ethics for Social Sciences. An online compendium of questionnaires in Turkish was shared with participants through online video game forums, in-game communication channels, and chat groups. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Inclusion criteria were being 18 years of age or older and playing online video games. A total of 490 participants filled the questionnaires. However, it was determined that 23 participants filled them out without reading it. Additionally, 136 participants did not meet the inclusion criteria. Analyses were conducted with the remaining 331 participants.

Mean age of the participants was 22.7 years (SD=4.73, min=18, max=70). Among the participants, 57.1% (n=189) were male and 42.9% (n=142) were female. It was found that 58% (n=192) were single and 42% (n=139) were in a romantic relationship. Among the participants, 58% (n=194) had a Bachelor's degree, 35.3% (n=117) had a high school degree, 3% (n=10) had a two-year university degree, and 3% (n=10) had a graduate degree. It was found that 72.2% (n=239) were not currently employed.

Participants reported playing an average of 2.82 hours of games per day (SD=2.14, min=1, max=14), with their longest continuous gaming experience lasting for an average of 5.95 hours (SD=3.88, min=1, max=15). The average duration of their experience with online multiplayer games was 7.20 years (SD=4.15, min=1, max=12). As for the participants' first-choice game genres, it was found that 34.1% (n=113) preferred first-person shooter games (FPS), 16.3% (n=54) preferred multiplayer online battle arena games (MOBA), 12.7% (n=42) preferred MMORPGs, 12.7% (n=42) preferred sports games, 5.1% (n=17) preferred real-time strategy games (RTS), and 19% (n=63) preferred other games. Among the participants, 81% (n=268) reported playing online video games with their real-life friends.

Measures

Personal Information Form. This form was prepared by the authors in order to collect data on sociodemographic and game-related characteristics. The form included questions about sex, age, educational level, employment status, relationship status, most preferred game genre, whether they played online games with their friends or not, daily time spent on games, and duration of longest game play.

Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form (IGDS-SF). IGDS-SF measures the symptoms and severity of IGD occurring over a 12-month period [Pontes, 2015]. This 9-item, 5-point Likert-type scale is unidimensional. Higher scores indicate risk for IGD. The Turkish version of the scale was found to be valid and reliable [Evren, 2018]. In the current study (n=331), Cronbach's alpha for the IGDS-SF was found to be 0.88.

Motives for Online Gaming Questionnaire (MOGQ). MOGQ measures the motivational basis of online gaming [Demetrovics, 2011]. The MOGQ is a self-report, 27-item, 5-point Likert-type scale including seven motivational dimensions: social, escape, competition, coping, skill development, fantasy, and recreation. The Turkish version of the scale was found to be valid and reliable [Evren]. In the current study, Cronbach's alpha for social, escape, competition, coping, skill development, fantasy, and recreation subscales were found as 0.81, 0.90, 0.87, 0.79, 0.89, 0.86, 0.90; respectively.

Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Scale-In General (BPNSS). BPNSS was designed to measure the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness [Deci, 2000; Gagné, 2003]. The BPNSS is a 21-item, 7-point Likert-type scale. A total score as well as subscale scores can be calculated. Higher scores indicate that needs are adequately met. The Turkish version of the scale was found to be valid and reliable [Bacanli, 2003]. In the current study, Cronbach's alpha for autonomy, competence, relatedness, and total need satisfaction were found to be 0.74, 0.66, 0.75, and 0.85, respectively.

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSS). The RSS is unidimensional and consists of 10 items. The Turkish version of the RSS was found to be valid and reliable [Cuhadaroglu, 1986]. In the present study, Cronbach's alpha for the RSS was found as 0.86.

Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale – Depression Subscale (HAD-D). The HAD assesses depression and anxiety [Zigmond, 1983]. The Turkish adaptation of the scale was conducted by Aydemir et al. [Aydemir]. In the current study, only the depression subscale was used. Cronbach's alpha for the depression subscale was 0.71 in the current sample.

Statistical Analysis

The SPSS 25 software and AMOS 22 were used for data analyses. Initially, to determine whether the data had a normal distribution, measures of kurtosis and skewness were examined. As the kurtosis and skewness values of the study variables fell within the range of +2 and -2, it was assumed that the data had a normal distribution [George, 2010]. Independent samples t-test was used to examine gender differences. Pearson product-moment correlations between continuous variables were calculated. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. Subsequently, a path analysis, which is a form of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), was conducted to test the study hypotheses. In SEM, goodness-of-fit indices are used for assessing model fit. Model fit was examined using the following indices: chi-square divided by degrees of freedom (0≤c2/df≤2), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA<0.08), goodness of fit index (GFI>0.90), adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI>0.90), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR<0.08), comparative fit index (CFI>0.90), normed fit index (NFI>0.90), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI>0.90) [Baumgartner, 1996; Bentler, 1980; Bentler, 1980a; Browne, 1993; Kline, 2011; Marsh, 2006; Schermelleh-Engel, 2003].

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Gender Differences

The participants' mean scores on IGDS-SF, MOGQ subscales, HAD-D, BPNSS, and RSS, as well as gender-based differences, were presented in Table 1. Men had significantly higher IGDS-SF scores than women (t(329)=-6.05, p<0.001). There were no significant differences in total and subscale BPNSS scores by gender. Mean escape motivation score of men was significantly higher compared to women (t(329)=-2.72, p<0.01). Men also scored significantly higher on the fantasy, social, competition, skill development, coping, and recreation motivations compared to women (t(329)=-4.81, p<0.001; t(329)=-7.35, p<0.001; t(329)=-6.23, p<0.001; t(329)=-5.79, p<0.001; t(329)=-4.15, p<0.001; t(329)=-5.59, p<0.001; respectively). Men also had significantly higher depression scores compared to women (t(329)=-2.51, p<0.05).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and gender differences

|

Variable |

Total Sample (n=331) |

Women (n=142) |

Men (n=189) |

t |

|||

|

X |

SD |

X |

SD |

X |

SD |

||

|

IGDS-SF |

17.87 |

7.20 |

15.24 |

6.24 |

19.79 |

7.25 |

-6.05*** |

|

BPNSS Total Score |

104.38 |

16.63 |

104.73 |

15.29 |

104.16 |

17.64 |

0.31 |

|

BPNSS Autonomy |

29.87 |

6.37 |

29.85 |

6.26 |

29.95 |

6.44 |

-0.13 |

|

BPNSS Competence |

28.35 |

5.83 |

28.10 |

5.43 |

28.57 |

6.11 |

-0.73 |

|

BPNSS Relatedness |

46.14 |

7.79 |

46.76 |

7.16 |

45.63 |

8.23 |

1.31 |

|

MOGQ-Escape |

10.20 |

4.75 |

9.39 |

4.51 |

10.80 |

4.86 |

-2.72** |

|

MOGQ-Fantasy |

7.85 |

4.22 |

6.60 |

3.60 |

8.78 |

4.41 |

-4.81*** |

|

MOGQ-Social |

8.36 |

3.67 |

6.77 |

2.66 |

9.55 |

3.86 |

-7.35*** |

|

MOGQ-Competition |

10.94 |

4.46 |

9.27 |

3.97 |

12.20 |

4.41 |

-6.23*** |

|

MOGQ-Skill |

9.83 |

4.49 |

8.25 |

3.65 |

11.01 |

4.70 |

-5.79*** |

|

MOGQ-Coping |

10.79 |

3.86 |

9.80 |

3.54 |

11.54 |

3.92 |

-4.15*** |

|

MOGQ-Recreation |

11.99 |

2.93 |

11.00 |

3.00 |

12.74 |

2.65 |

-5.59*** |

|

Depression |

7.06 |

3.67 |

6.48 |

3.56 |

7.50 |

3.71 |

-2.51* |

|

Self-Esteem |

4.50 |

1.64 |

4.45 |

1.55 |

4.56 |

1.69 |

-0.62 |

Notes. * — p<0.05, ** — p<0.01, *** — p<0.001; IGDS-SF — Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form, BPNSS — Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Scale, MOGQ — Motives for Online Gaming Questionnaire.

Table 2. Pearson product-moment correlations between study variables

|

Variable |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

|

|

1 |

IGDS-SF |

1 |

-,34*** |

,61*** |

,63*** |

,46*** |

,48*** |

,52*** |

,35*** |

,40*** |

,33*** |

-,37*** |

|

2 |

BPNSS |

- |

1 |

-,37*** |

-,33*** |

-,03 |

-,11* |

-,22*** |

-,04 |

-,01 |

-,54*** |

,62*** |

|

3 |

M-E |

- |

- |

1 |

,74*** |

,48*** |

,50*** |

,75*** |

,43*** |

,51*** |

,34*** |

-,39*** |

|

4 |

M-F |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

,55*** |

,45*** |

,66*** |

,38*** |

,54*** |

,28*** |

-,27*** |

|

5 |

M-SOC |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

,54*** |

,54*** |

,46*** |

,64*** |

,06 |

-,03 |

|

6 |

M-COM |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

,63*** |

,53*** |

,57*** |

,16** |

-,12* |

|

7 |

M-COP |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

,60*** |

,59*** |

,24*** |

-,25*** |

|

8 |

M-R |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

,47*** |

,12* |

-,09 |

|

9 |

M-SD |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

,12* |

-,04 |

|

10 |

DEP |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

-,55*** |

|

11 |

SE |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

1 |

Notes. * — p<0.05, ** — p<0.01, *** — p<0.001; IGDS-SF — Internet Gaming Disorder Scale-Short Form, BPNSS — Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction Scale, M-E — Escape motivation, M-F — Fantasy motivation, M-SOC — Social motivation, M-COM — Competition motivation, M-COP — Coping motivation, M-R — Recreation motivation, M-SD — Skill development motivation, DEP — Depression, SE — Self-esteem.

Path Analysis

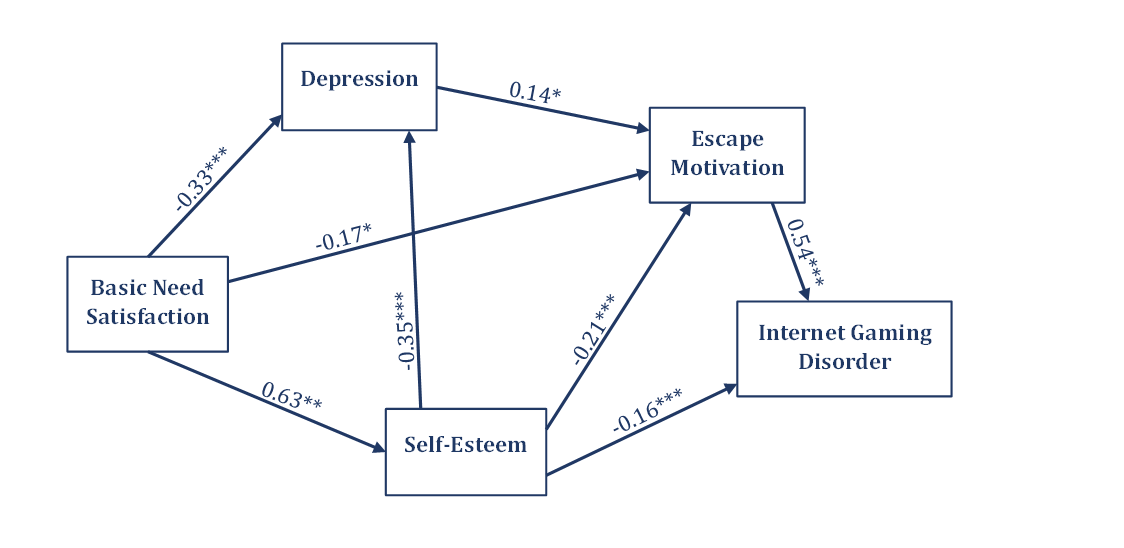

The proposed integrative path model for explaining IGD (see Fig. 1) was tested using the AMOS software. According to analysis, the model did not show good fit (c2/df=could not be calculated, GFI=0.53, AGFI=0.30, NFI=1.00, CFI=1.00, TLI=could not be calculated, SRMR=0.00, RMSEA=0.40). Examination of estimates showed that paths from depression to IGD and from BPNS to IGD were insignificant (p>0.05). These paths were removed from the model and analysis was rerun. The revised model showed excellent fit (c2/df=1.46, GFI=0.99, AGFI=0.97, NFI=0.99, CFI=0.99, TLI=0.99, SRMR=0.01, RMSEA=0.03). Standardized beta weights were shown in Fig. 2. Satisfaction of basic psychological needs directly and significantly predicted depression, escapism, and self-esteem. Self-esteem directly and significantly predicted depression, IGD, and escapism. Depression directly and significantly predicted escape motivation, while the escape motivation directly and significantly predicted IGD. The effect of basic psychological need satisfaction on IGD was serially mediated by self-esteem, depression and escape motivation. This effect was also serially mediated by depression and escape motivation. In addition, the association between inadequate satisfaction of basic psychological needs and IGD was mediated by self-esteem.

Fig. 2. Revised path model with standardized β coefficients

Based on the above analyses, hypothesis 1 (H1) was rejected since satisfaction of basic psychological needs was not directly associated with IGD. Hypothesis 2 (H2) was accepted as the association between inadequate satisfaction of basic psychological needs and IGD was serially mediated by depression and escape motivation. Hypothesis 3 (H3) was also accepted as the association between inadequate satisfaction of basic psychological needs and IGD was mediated by self-esteem. Finally, hypothesis 4 (H4) was accepted as the association between inadequate satisfaction of basic psychological needs and IGD was serially mediated by self-esteem, depression, and escape motivation.

Discussion

The main aim of the current study was to investigate relationships between IGD, basic psychological need satisfaction, depression, self-esteem, and escape motivation through an integrative path model. It was hypothesized that (1) satisfaction of basic psychological needs is negatively associated with IGD; (2) the association between inadequate satisfaction of needs and IGD is serially mediated by depression and escape motivation; (3) the association between inadequate satisfaction of needs and IGD is mediated by self-esteem; and (4) the association between inadequate satisfaction of needs and IGD is serially mediated by self-esteem, depression, and escape motivation. Results of the path analysis provided support for H2, H3, and H4, while H1 was rejected. Satisfaction of basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness did not directly predict IGD but had indirect effects on the outcome variable through serial mediators; namely, self-esteem, depression, and escape motivation. Inadequate satisfaction of basic psychological needs reduces self-esteem, which in turn leads to depression. Depression results in playing online video games with the motivation to escape from real-life problems and this, in turn, leads to excessive online gaming.

Analysis yielded other paths of mediation between inadequate satisfaction of basic psychological needs and IGD. These paths included self-esteem as sole mediator; escape motivation as sole mediator; and depression and escape motivation as serial mediators. Thwarting of basic psychological needs in real life depletes self-esteem and this, in turn, leads to IGD. Similarly, thwarting of basic psychological needs leads to playing online games with the motivation to escape from real-life problems, which in turn leads to IGD. Finally, inadequate satisfaction of basic needs may result in depressive symptoms, which leads to escapism and then to IGD.

Previous research provided support for the above findings. Empirical studies found that young people whose basic psychological needs are unmet in daily life indulge in online video games [41; 57; 64; 71; 85; 87;91]. The role of self-esteem in IGD development is also evident [Kavanagh, 2023; Kavanagh, 2024; Kochetkov]. Several studies reported a mediating effect of depression on IGD [Chen, 2021; Fazeli, 2020; Ryu, 2018; Scerri, 2019]. These reports are all in line with the results of the current study.

In one study, a serial mediation between basic psychological need satisfaction deficits and IGD through self-esteem and depression was reported [Scerri, 2019]. The researchers found that need satisfaction deficits reduced self-esteem, which elucidated depressive symptoms and this led to IGD. In our path model, depression was not a significant predictor of IGD but had an indirect effect on IGD through escapism. It can be speculated that depressive symptomatology does not lead to IGD in the absence of escape motivation. The clinical significance of the escape motivation was also indicated in meta-analyses of gaming motivations and IGD [Melodia, 2022; Wang H.-Y, 2022]. The current study provided support for the clinical importance of escapism in terms of IGD. Individuals whose basic psychological needs are unmet have lower self-esteem, which predisposes them to depression. In order to cope with disordered mood and real-life problems, they turn to online video games, which seem to serve as a distraction. Thus, excessive gaming is negatively reinforced as a way of escaping from psychosocial problems [Hagstrom, 2014; Shalaginova]. Furthermore, the current study supported the notion that escapism is among the defining symptoms of IGD as proposed by the DSM-5.

In the current study, it was found that men had higher levels of IGD than women. This finding is consistent with other research [Dong, 2022; Wang, 2017]. Similar to chemical addictions and gambling, being male is a risk factor for IGD. Men may be more susceptible to addiction-related cues such as advertisements, whereas women engage in addictive behaviors due to emotion dysregulation [Dong, 2018]. Men also had higher gaming motivation scores across all seven dimensions compared to women.

In terms of IGD, clinical implications can be deduced from the findings of the study at hand. Psychosocial interventions in either individual or group format can prioritize finding alternatives to escapism among risk groups with lowered self-esteem and unmet basic psychological needs. Cognitive behavioral interventions which focus on expanding one’s coping repertoire can be especially beneficial in reducing escapism. Acquisition of various coping skills would also contribute to self-esteem and the capacity to meet basic psychological needs in daily life, which would in turn protect one against IGD and depressive symptoms.

There are certain limitations to the current study. First, the study design was cross-sectional. Since excessive gaming tends to begin in young ages, future studies may employ longitudinal designs in order to examine developmental tracks leading to IGD in terms of Self-Determination Theory. Also, such designs would allow researchers to make causal inferences. Second, the sample size of the current study reduces the generalizability of the findings. Third, due to sample size limitations, statistical comparisons based on game genres could not be conducted, albeit it is reported that certain game genres such as MMORPGs and FPS games are more closely related to IGD. Finally, since it was aimed to test our model among adult gamers, we set the inclusion criteria for age as being 18 or older. The final sample included gamers aged between 18–70 years old. This range includes gamers from different developmental periods including emerging adulthood, adulthood, middle adulthood, and advanced adulthood. Albeit 88.2% of the participants were aged between 18–25 and the mean age of the sample was 22.7 (SS=4.73), which corresponds to both emerging adulthood and adulthood, age or developmental characteristics of the participants may have acted as a confounding variable in the current study. This limitation may be addressed in future studies via using different developmental clusters of participants and comparing their data.

In conclusion, IGD is a significant mental health issue throughout the world, especially among youth. Excessive gaming is a behavioral addiction which disrupts normal life. Better understanding the causes of this condition is necessary for its treatment and prevention. This study aimed to test an integrative model of IGD, in which thwarting of basic universal psychological needs of relatedness, autonomy, and competency disrupts self-esteem and mood, which in turn results in escapism and excessive gaming. Accordingly, psychotherapeutic interventions addressing the factors in this integrative model may prove to be beneficial.