Introduction

The experiences of autistic individuals in Saudi Arabia remain underexplored, even as global awareness and care for autism continue to progress. In a society undergoing rapid industrialization and social transformation, it is essential to understand the specific challenges encountered by those with autism. While services for individuals with disabilities have improved in Saudi Arabia, significant gaps persist, particularly regarding independent living, romantic relationships, and societal attitudes. This research aims to examine the daily lives of autistic individuals in Saudi Arabia to address these deficiencies. It seeks to gather insights into their views on independent living and marriage, their satisfaction with available community resources, and their perceptions of public attitudes towards autism. This study is crucial for informing policy reforms, enhancing service delivery, and fostering an inclusive society that recognizes and supports the needs of individuals with autism.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental syndrome characterized by differences in behavior, communication, and social interaction (American Psychiatric Association, 2022). As our knowledge and diagnosis of autism have grown, so too have the numbers of autistic people fighting for their rights, independence, and social inclusion (Ne'eman, 2021). Being able to live independently is a significant accomplishment for many autistic people. In addition to living without caregivers, this entails handling daily tasks, employment, and personal finances (Tantam, 2022). Self-esteem and life satisfaction can increase with independence, but independence often calls for appropriate support networks and services tailored to the unique needs of individuals with autism (Shattuck et al., 2020; Qin et al., 2024; Horwood et al., 2021). The study found that the social communication and executive functioning issues that autistic adults frequently encounter impede them from becoming independent (Russell et al., 2020).

Marriage and romantic relationships are significant life events that support happiness and personal fulfillment. Like their neurotypical counterparts, adults with autism want deep connections and alliances. However, individuals may face particular difficulties courting, forming, and sustaining relationships due to social communication impairments (Mazurek, Kanne, 2010; Strunz et al., 2017). According to another research, individuals with autism may have different views on marriage and relationships (Soares et al., 2021). A lot of autistic adults express a need for connection and companionship despite having difficulty interacting with others. Family members of adults with autism expressed differing opinions about their loved ones' suitability for marriage in a study (Neu, Bradford, 2025). While some acknowledged their need for companionship, others voiced concerns about their social skills.

To become independent and form healthy relationships, people with autism spectrum disorders mainly depend on community services. Healthcare, mental health support, job assistance, housing, and social services are some of these services (Nord et al., 2013). The well-being and satisfaction levels of adults with autism are significantly impacted by the efficiency, availability, and caliber of these services. Services must be specially designed to meet their needs to promote empowerment and inclusion (Song et al., 2025). There is a profound influence of supportive services, like housing aid and job training, in easing the transition of autistic adults to independent living (Amaral et al., 2019).

On the other hand, the way the public perceives autism may have a big effect on the well-being of those who have it. Positivity and acceptance can result in greater inclusion and opportunities, but negative perceptions and prejudice can build significant obstacles (Aube et al., 2020; Botha, Dibb, Frost, 2020). Understanding how public opinions impact autistic adults' daily lives is crucial to devising strategies to promote greater societal acceptance and reduce stigma.

Theoretical Framework

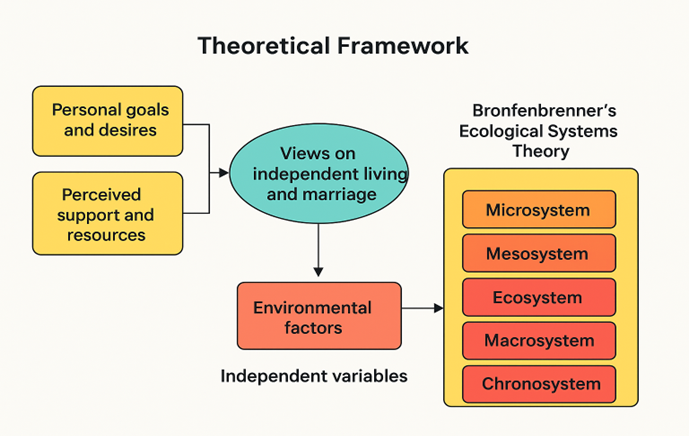

This research examines the views of autistic adults regarding living independently and marriage, considering both individual and environmental factors. The primary independent variables include personal goals and desires, perceived support and resources, and wider environmental elements such as family, community, societal norms, and policy context. The dependent variables are the participants' views on independent living and marriage. Although this study did not use a theoretical model as a direct analytical framework, Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory provides a valuable conceptual basis for understanding the complex environmental influences on human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Figure 1 shows this theory which outlines the five interconnected systems—microsystem, mesosystem, ecosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem — that offer a contextual framework for interpreting how various environmental and societal factors might impact the experiences of autistic adults. The microsystem includes immediate environments and relationships, such as family, close friends, and caregivers, who may shape individual perspectives on independence and relationships (Siller, Sigman, 2002). The mesosystem involves interactions between different microsystems, like how family dynamics intersect with community or educational services (Boyd et al., 2010). The ecosystem consists of broader structures that do not directly involve the individual but still have an impact, such as healthcare policies, workplace systems, and access to autism-related services (Thomas et al., 2007). The macrosystem encompasses overarching cultural values, legal policies, and societal attitudes toward autism, marriage, and autonomy within Saudi society (Alkhateeb, Hadidi, Mounzer, 2022). The chronosystem captures the effects of life transitions and societal changes over time, such as increased public awareness and evolving support frameworks for individuals with autism (Kapp et al., 2013).

By employing this theory as a guiding perspective, the study places personal experiences within a broader ecological context, emphasizing how individual, interpersonal, institutional, and societal layers may converge to shape the aspirations, challenges, and support systems of Saudi autistic adults seeking independent living and marriage.

Purpose of the Study

This qualitative study aims to explore the experiences of individuals with autism in relation to independent living, romantic partnerships, and marriage. It also seeks to understand their perceptions of public attitudes regarding autism and their level of satisfaction with community services.

Research Questions

- How do adults with autism view their experiences living on their own?

- What difficulties and triumphs do adults with autism face in romantic relationships and marriage?

- How happy are adults with autism with the community services that are offered to the.

- How does the general public's perception of autism affect adults with autism?

Significance of the Study

The results of this study will contribute to our understanding of the unique experiences that adults with autism have. It will provide information for the development of more effective community services, support changes to the law, and promote public acceptance and awareness. By recording the voices of adult autistic people and highlighting their insights and issues, the current study's findings will give policymakers, service providers, and society crucial information to help and involve autistic individuals in all aspects of life. The aim of the research is to support adults with autism to live fully, love, and do so with dignity and respect in an accepting society.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from the First Autism center, located in Alshata district, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia to identify the lived experiences of autistic adults regarding their ability to get marriage and live independently. The First Autism Center in Jeddah is one of the most important projects implemented by the Al-Faisaliah Women’s Charitable Society in Jeddah in 1412 AH/1992 AD. It is the first center of its kind in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and it is considered one of the most important leading social institutions that provide the best educational and rehabilitation programs for people with autism and providing continuous family support. This is the only center including adult autistic group.

In the qualitative study, autistic adults were interviewed with their health care providers who helped in recruiting autistic adults who are in the average level of intellectual ability, able to talk, and they are 20 years and above. This inclusion of accounts from health care providers provided an opportunity to extend the focus of the qualitative study to include their experiences of an additional information of autistic adults some of whom were not able to report about their own lives. Whilst this inclusion extends the size and general diversity of samples on whom we report, broader representation of autistic individuals with learning disability is not assumed.

Participant recruitment

The research involved seven adults with autism who were receiving services at a specialized autism center in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Out of the eleven individuals who regularly attended the center, only these seven met the study's specific inclusion criteria. The criteria were as follows:

- A formal diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) documented in the individual's medical records and confirmed by the center's interdisciplinary team.

- Being 18 years or older and identifying as an adult with ASD.

- Possessing basic verbal communication skills, enabling them to comprehend and respond to semi-structured interview questions without needing augmentative communication.

- The capability to provide informed consent, either independently or with the assistance of a legal guardian if necessary.

- Having functional cognitive and adaptive abilities that align with an average or borderline intellectual level, as assessed by their most recent psychological evaluation.

Four individuals were excluded for the following reasons: two encountered significant communication challenges that rendered verbal interviews impractical, one opted not to participate, and one had recently joined and lacked sufficient interaction with the center or support services to offer meaningful insights on the study topics.

One participant, who had a mild intellectual disability (IQ score between 50–70), was included due to strong adaptive functioning skills and the ability to communicate effectively about lived experiences. Including this participant enriched the data by providing a broader representation of autistic adults in Saudi Arabia. Seven out of eleven autistic adults were recruited from the first autism center. Each autistic adult was interviewed individually, with a healthcare provider present, to gather maximum information about the study sample, including age range, timing of autism diagnosis, and residence locations. Participants meeting the inclusion criteria were predominantly recruited, and sampling continued until no new themes emerged from the data. All participants were contacted face-to-face for interviews lasting between one hour and 75 minutes, depending on their ability to respond to the interview questions.

Materials

Potential participants were sent an invitation letter, a study information leaflet, and a consent form for the qualitative study.

Interview Guide Development and Adaptation:

The Focus Group Discussion Guide (FGDG) for autistic adults in this study was specifically crafted to meet the cognitive and communicative needs of adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The questions were adapted from the original guide used for healthcare providers and simplified to ensure clarity, relevance, and sensitivity. This adaptation process was guided by recommendations from previous research on interviewing neurodiverse populations (Nicolaidis et al., 2019; Scott-Barrett, Cebula, Florian, 2019). Special attention was given to using plain language, allowing extra response time, and creating a supportive, low-stress interview environment. As no standardized universal guide exists for all ASD contexts, the version used here was designed with input from clinical experts and based on guidelines for inclusive research practices with autistic individuals. For reference, frameworks like the AASPIRE Interview Guidelines1 were consulted. These emphasize participant comfort, respect for autonomy, and flexible communication strategies. A customized Focus Group Discussion Guide was developed for use with autistic adults, based on best practices for interviewing neurodiverse populations. The full version of the guide is provided in (Appendix I).

Focus Group Discussion Guide (FGDG) Topics:

The FGDG for autistic adult participants was designed to explore their lived experiences, perceptions, and aspirations regarding independence and relationships.

The guide consisted of four parts:

Part I: Warming-Up Phase (Demographic Questions). This section gathered basic background information, including age, education, employment status, marital status, and duration of involvement with the center. These questions provided context for understanding each participant’s life situation and support network.

Part II: Engagement Phase (Ice-Breaking Questions). This phase introduced participants to the discussion by inviting them to share personal insights about what autism means to them, their comfort with social interactions, and their satisfaction with the services they receive. These questions were designed to build rapport and ease participants into the discussion.

Part III: Exploration Phase (Key Questions). This section focused on an in-depth exploration of the participants' abilities, challenges, and goals related to: Independent living (e.g., daily tasks, desire to live alone, support needs). Romantic relationships and marriage (e.g., interest in dating, barriers to relationships, social perceptions). Social support and inclusion (e.g., understanding from others, types of support needed) Coping strategies and personal advice for others on similar journeys.

Part IV: Wrapping-Up Phase (Closing Question). In this phase each participant was asked about “Would you like to share anything else that you think is important or that we haven’t talked about yet?"

The guide was developed using plain, accessible language, with consideration for neurodiverse communication preferences, based on prior research and ethical guidelines for working with autistic adults.

Data collection

Participants were offered an opportunity to ask any questions about the study prior to giving informed written consent. All interviews (lasting 45–90 minutes) were audio-recorded. Interviews were conducted by the researcher with one of the health care providers who has additional training for working with autistic adults’ participants. Reasonable adjustments were made to accommodate the sensory needs and preferences of each participant.

Analysis

All interviews were transcribed, authenticated, and made anonymous. Following this, data analysis was conducted, and thematic analysis was initiated using the framework method. This involved constant comparison (Nicolaidis et al., 2016) and deviant case analysis to reinforce the internal validity of the findings (Gale et al., 2013. Typologies were fashioned, and descriptive and explanatory categories were established. The data was then independently coded for every transcript from adults with autism (Merriam, 2020). The interpretation of the data was finalized and arranged under thematic banners. To guarantee credibility, the adult transcripts were independently scrutinized, and consensus conferences were held with the two healthcare providers who participated in the interviews (Braun, Clarke, 2021). Throughout the analysis process, significant emerging findings were presented and debated to acquire interpretative contributions from the healthcare providers who interviewed many autistic individuals (Nowell et al., 2017).

The present study contrasted separate analyses, with a particular emphasis on subjects pertaining to the 'experiences of the adult.' The general themes within this category were consistent across both datasets. The adults' dataset provided more detailed descriptions of the constituent themes, enabling a focus on the perspectives of autistic adults while also considering reports from healthcare providers who support and advocate for autistic adults.

In this research endeavor, participants were initially identified utilizing a pseudonym, followed by their age at the time of the interview, autism spectrum disorder diagnosis, and age at diagnosis (AaD). Identifiers for healthcare providers (HCPs) comprise information about their relationships with other colleagues in the center, observations of the sexual desire of autistic adults (such as looking for sexual content online), their hobbies, and their history of engagement, as reported by the HCPs. Illuminating quotes have been selected to represent the themes and have been incorporated into the text.

Ethical considerations

The study underwent a formal approval process, beginning with submission to the research unit at the College of Nursing, Jeddah, KAIMRC, and IRB (NRJ22J/048/02). After receiving approval, the study was then submitted to the Ministry of Education for further approval. Once the necessary approvals were obtained, the manager of the first autism center was approached to seek approval from the parents of the autistic adults. Although all participants in this study were adults (18 years or older) diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), approval was obtained from their legal guardians prior to data collection. This step was in accordance with the policies of the Saudi Arabian Ministry of Health (MOH), which classifies individuals with psychiatric or neurodevelopmental disorders including autism as a vulnerable population. As such, individuals in this group are considered legally restricted in providing independent informed consent for participation in research studies. Therefore, guardian consent was obtained through coordination with the center’s administration, ensuring adherence to national ethical and legal standards. Additionally, verbal or written assent was also obtained from participants themselves to respect their autonomy and willingness to participate. The study subjects were then informed about the study's purpose and procedure. They were assured that their participation was voluntary and that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time without facing any penalties. It was emphasized that their responses would remain anonymous, and their data would be kept confidential within the records and office of NGHA and only the researcher of the study has access to all transcripts.

Results

Table 1 displayed autistic Youth Sociodemographic Data: The study's young participants, aged 18–32 years, represent a relatively youthful demographic. Notably, most of these youths (n = 5 (71.4%)) report no parental consanguinity, indicating that most parents are not closely related. The data also sheds light on the challenges faced by individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and associated conditions. Many of them have limited or no formal education and are currently unemployed. Additionally, common co-occurring mental health issues, such as anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, further impede their employment prospects. This information emphasizes the significant impact of ASD, intellectual disabilities, and mental health challenges on educational and job outcomes, highlighting the urgent need for enhanced support systems to address these barriers.

Table 1

Distribution of the participant according to their demographic characteristics — autistic adults (N = 7)

|

Pseudonym |

Age at interview |

Age at diagnosis |

Autism spectrum diagnosis & LD |

Co-occurring mental health diagnoses reported |

Education level |

Parents’ Consanguinity relationship |

History of ASD or MD |

|

Mr A |

32 |

6 |

Autism and LD |

Anxiety |

No formal qualifications |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Mr Z |

26 |

5 |

ASD and LD |

Phobia (Pyromania) |

No formal qualification (elementary) |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Mr M |

18 |

5 |

ASD |

Moderate ID |

No formal qualification |

None |

None |

|

Mr A |

30 |

6 |

ASD and LD |

Anxiety |

No formal qualification |

None |

None |

|

Mr M |

23 |

5 |

AS |

Depression, Anxiety, OCD |

Integrated education |

None |

Yes |

|

Mr H |

26 |

12 |

ASD & LD |

Anxiety |

No formal qualification |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Mr M |

28 |

4 |

ASD & ID |

Depression, Anxiety |

No formal qualification |

None |

None |

Notes: AS — Asperger syndrome; ASD — autism spectrum disorder; OCD — obsessive compulsive disorder; LD — learning disability; ID — intellectual disability.

Table 1 displayed autistic Youth Sociodemographic Data: The study's young participants, aged 18–32 years, represent a relatively youthful demographic. Notably, most of these youths (n = 5 (71.4%)) report no parental consanguinity, indicating that most parents are not closely related. The data also sheds light on the challenges faced by individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) and associated conditions. Many of them have limited or no formal education and are currently unemployed. Additionally, common co-occurring mental health issues, such as anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, further impede their employment prospects. This information emphasizes the significant impact of ASD, intellectual disabilities, and mental health challenges on educational and job outcomes, highlighting the urgent need for enhanced support systems to address these barriers.

Table 2 shows the demographic and clinical features of the autistic adult participants (N = 7) show a mostly young adult group, with an average age of 26.14 years (± 4.69) and an average diagnosis age of 6.14 years (± 2.57), suggesting early detection of autism. Many participants (85.7%) were identified as having autism along with a learning disability or intellectual disability, whereas just one participant (14.3%) had Asperger’s syndrome, indicating a greater level of functioning. A significant percentage (85.7%) indicated the presence of co-existing mental health issues like anxiety, depression, OCD, or phobias, highlighting the intricate mental health requirements of this population. In terms of education, 71.4% lacked formal qualifications, potentially restricting their chances for employment and independent living. Moreover, 42.9% of participants indicated parental consanguinity, while 57.1% had a familial background of autism or mental illnesses, which are significant genetic and cultural factors in the Saudi Arabian setting. In summary, these results emphasize the complex obstacles encountered by autistic adults regarding education, mental well-being, and autonomy, and stress the need for personalized support services.

Table 2

Mean and SD of demographic characteristics of the autistic individuals (N = 7)

|

Variable |

Mean ± SD |

|

Age at Interview (years) |

26.14 ± 4.69 |

|

Age at Diagnosis (years) |

6.14 ± 2.57 |

|

Variables |

No (%) |

|

- Participants Diagnosed with Asperger’s |

1 (14.3%) |

|

- Participants with Learning Disability or ID |

6 (85.7%) |

|

- Co-occurring Mental Health Diagnoses Present |

6 (85.7%) |

|

- No Formal Education (Level 1) |

5 (71.4%) |

|

- Parental Consanguinity (Yes) |

3 (42.9%) |

|

- Family History of ASD/MD (Yes) |

4 (57.1%) |

Figure 2 underscores the diverse challenges and advantages faced by autistic youth, corroborating Theme 1: Talents/Strengths and Abilities of Autistic Youth, which highlights their unique nature and potential for independence in both activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs). Theme 2 highlights the importance of acknowledging their distinct skills while tackling Communication Barriers like slow replies, repetitive speech (echolalia), lack of eye contact, and challenges in maintaining conversations, which hinder effective interaction. Theme 3 recognizes the influence of Autism-Related Bullying, such as overstimulation in social environments, societal judgment, and a lack of understanding regarding the needs of autistic adults, which frequently results in isolation and negatively impacts mental health. Additionally, theme 4 examines the intricacies of marriage and relationships, such as anxieties about genetic tendencies for autism, the compromises necessary for family living, and the difficulties posed by social expectations. Ultimately, the theme 5 and 6 explores Community and Systemic Challenges, including stigma, misunderstandings, concealed autism from high functioning, skepticism about autistic capabilities, and opposition to novel treatment methods. Tackling these challenges necessitates a comprehensive strategy, which involves increasing community awareness, improving training for families and caregivers, and securing strong governmental backing to foster the adaptation and empowerment of autistic young individuals.

Themes of the study

Theme 1: Talents/strengths and abilities of the autistic youth

Autistic youth may display a range of strengths and abilities that can be directly related to their diagnosis, including:

Specialized character for autistic youth: They are very punctual. Strongly adhere to rules. Able to concentrate for long periods when motivated. Have a drive for perfection and order. Multitalented autistics especially in math (“We prefer routine, strict in the time factor, my mother told me that I am perfect, and she likes that”). Share in Special Olympics and competitive activities (“I won an award in swimming from Egypt”, “I am clever at playing football”, “I am clever in using computers and Baristas”, “Computers and baristas are interesting to me”).

Autistic youth and activities of daily living (ADLs) / Instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs): Activities of daily living (ADLs) are activities that people engage in on a routine basis, such as brushing their teeth, preparing a meal, and caring for their child. Independence with ADLs is associated with better outcomes in independent living, education, employment, relationships, and mental health. The participation is according to the autism severity level. Higher severity levels show greater difficulty and parental dependence in ADL.

Some of the studied autistic youth assist in instrumental activities of daily living as cooking. Most of them are independent in their daily activities (“I can share my mother in the kitchen and help in cooking”, “I can do the shopping and deal with money with no problem”, “I am independent in everything even taking a shower”).

Theme 2: Communication barriers among autistic youth

Autism-related symptoms affect autistic communication skills. These symptoms may be more noticeable or disruptive in some autistic people than others. Communicate in different ways than allistic (non-autistic) people.

Delayed responses and reaction: “One of the communication barriers facing us is the delay in response and reaction, we can't respond as fast as others”, “Others avoid communicating with us because they need a rapid response that we can't”.

Repetitive speech “echolalia”, unnecessary repeating words and phrases: “Some of my friends here speak in a flat or monotonous fashion 'flat' tone of voice and repeat certain phrases over and over that make others feel that it is disgusting.”, “Some also engage in repetitive motions or behaviors”.

Avoid eye contact: “Some of my friends avoid eye contact during conversations or other social situations due to sensory overload” (P1).

Hard to hold a conversation: “Some of my friends take things too literally, so they can’t communicate and understand, they even can’t start communication.”. Others have difficulty understanding facial expressions and inferring communicative intent based on context which leads to missing the unspoken aspects of conversation.

Theme 3: Autism-related bullying attitude of the community

Individuals with autism are at a higher risk of experiencing bullying due to their social interaction difficulties. The unique behaviors and communication styles associated with autism can make them targets for bullying. Bullies may exploit their vulnerabilities, lack of social skills, and difficulties in understanding social dynamics.

Autistic youth avoid gathering and overstimulated environment: “We avoid any stimulating environment and avoid gathering even to pray we prefer if there is a specialized mosque for autistic people to avoid bullying attitude”, “I avoid socialization to avoid a bullying attitude”.

Criticizing community: Autistic people are more vulnerable to being the victim of repeated insults. Youth with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder benefit from support to bring out their potential, and a safe space to be their unique self and protect themselves from bullying (“In the past, I preferred to play with other children who were ready to do but unfortunately, their families refused and called me ‘crazy’ which made me cry”, “Other people were laughing at me instead of being my friends”).

On the other side, because autistic youth cannot always clearly communicate their thoughts and feelings, we should be mindful that these same youth may inadvertently offend a friend or classmate without even knowing it. This can cause a backlash and increased acting out against the child with autism (“I don’t know why they attack me”).

Effects of bullying on autistic youth: Youth with high-functioning autism who are victims of bullying are also likely to experience negative mood or self-image, i.e., feeling weird and different, shutting down; a loss of interest in activities they used to enjoy, outbursts of aggression, perhaps without a clear trigger (“After my exposure to bullying attitude, I can't engage again in any group activities, I prefer to be alone”, “I noticed that my friends become aggressive and may harm others”).

Theme 4: Autistic youth and marriage

Marriage requires a large amount of responsibility for both parties, many sacrifices, and financial security for future children.

Some of the studied youth reported that the single greatest impact that autism can have on a marriage between two people is problems with communication. Talking and carrying on a conversation is harder to do when someone interprets the things said differently. But this doesn't only concern verbal communication (“Poor communication leads to marriage failure”). Autistic youth is characterized by the inability to read body language and social cues. Although such abilities are easy for most to possess, anyone with autism might need help in understanding things said to them in conversation (“I want to marry an autistic girl, similar to me and I want to have a family like my brothers”, “In the past; I was engaged but I couldn’t understand my fiancée, she was using some non-verbal communication which I can’t understand anymore”).

Fear of having autistic babies in the future: Fear of having autistic babies; autism can also impact marriage through the greater chance of couples having a baby that's autistic (“I am not ready to marry because I have mood swings, and I can switch at any time. Maybe I am enthusiastic to marry but unfortunately, I can’t”).

Divorce and Autism: Unfortunately, divorces between couples where one is autistic frequently happen. Mild symptoms, with a high-functioning autistic spouse, may affect this relationship, high functioning decreases the chance of divorce. With the right amount of patience and understanding, the disorder itself could become an afterthought having nothing to do with the daily lives of married couples (“Autistic youth who can handle situations safely, handle money effectively, able to understand, able to differentiate between what is right and wrong can marry and have their independent life”, “Autistic youth outside the kingdom can marry but here they can’t due to lack of awareness and preparation and acceptance”).

Theme 5: Autism-related challenges in the community

Autism stigma and misconception: One significant challenge is the stigma and misconceptions surrounding autism. Limited understanding and misconceptions about autism can lead to social exclusion, stereotypes, and discrimination, hindering the opportunities for youth with autism to develop meaningful social connections (“Stigmatization in the community is one of the main challenges facing autistic youth, I felt this stigma, and my mother suffered a lot from it”, “Fear and anxiety among people in malls for example when notice autistic youth, I believe that they consider us odd and strangers”, “On the other hand, some people show positivity toward autistic youth which might be due to raising public awareness”).

Routines and rituals adherence: Adherence to routines and intense interests can all impact their ability to engage in meaningful social connections. Individuals with autism often rely on routines and rituals to create predictability and reduce anxiety. While routines can provide structure and comfort, they may also contribute to social interaction difficulties. Insistence of following specific routines or difficulty adapting to changes in plans can affect social flexibility and spontaneous interactions (“I can’t break my routine anymore. I can’t change anything even my place of sitting”, “If someone tries to change my routine I can’t accept him, I can’t communicate till return to my habits”).

Difficulty making friends: Making friends can be a difficult task for those with autism due to challenges with social norms and nonverbal communication. These challenges can impede the formation of meaningful social connections. On the other hand, others with mild degrees of autism can make friends and maintain this relationship (“I have some friends outside the center, but my friend can’t accept to make friends outside”, “We prefer known people rather than strangers”).

Social media and autistic friendship — Online Networks and Apps: Social media use was significantly associated with high friendship quality in adolescents with ASD, which was moderated by the adolescents' anxiety levels (“I can use social media and WhatsApp to make friends without sharing photos”, “I prefer electronic friendship as an easy method to make friends. That’s the way I communicate”, “Watching TV is better than communicating with people and making friends to avoid bullying”).

Mistrusting the abilities of autistic youth: The community mistrusts autistic abilities, talents, and IQ (“One of the challenges facing us is the family mistrust issue. They mistrust our abilities. They feel afraid all the time and don’t leave us alone”, “Some of our families refused new treatment modalities and didn’t permit us to try”).

Lack of resources and rehabilitation: Limited access to recommended autism services. Specialized interventions for autistic youth are lacking in addressing behavioral disorders (“The most common service available for us is behavioral therapy and physiotherapy. But unfortunately, we have limited access to specialized centers for youth and adults. We have no access to specialized clubs and so on”).

Theme 6: Autistic youth adaptation skills

Raising community awareness and enhancing training: Prepare autistic youth to be ready for adult life and marriage (“Some teachers talk with us to guide us to be independent”, and “The restriction in our environment not in us”).

Share in competitive activities like the Olympics (“Organizing sports and artistic events with the participation of people with autism is important for us”).

Training families to deal with autistic symptoms (“Sometimes hearing the Quran is important to calm down”).

Family support: Family support is highly important, and their training is crucial to deal appropriately with autistic youth. Delayed family help and support affect autistic youth progress (“My family can't support me; they have money and prefer to give money to others to support us”, “My family supports me financially; they give me a chance to share in my home activities”).

Teachers and caregivers support and patience: Patience is an invaluable trait when working with Autistic youth. Autistic youth are individuals who have different needs, and their behavior can be unpredictable and challenging. Patience is needed to create a successful learning environment and to maximize the potential for positive outcomes (“Patience is important in dealing with autistic youth”, “Patience teachers and caregivers support us, help us to be more productive and gain special talents”).

Governmental support: Providing monthly support for people with special needs such as autism and providing comprehensive rehabilitation for them (“Our government gives us comprehensive rehabilitation and they support us financially to be productive members of our community”).

Discussion

The findings of the current qualitative study emphasize significant aspects of the everyday lives of individuals with autism, particularly concerning their autonomy and regular activities. The exceptional traits and capabilities of autistic youth, such as punctuality, compliance with rules, focus, and pursuit of excellence, are valuable assets that can enhance their self-sufficiency. Studies show that individuals with autism frequently excel in areas they are passionate about, ranging from specialized subjects like mathematics or technology to sports and competitive pursuits. These interests and talents serve as a strong foundation for successful engagement in personal and professional settings (Flick, 2022; Jadav, Bal, 2022).

Concerning activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), the level of independence achieved by individuals with autism varies. While some may need assistance, others exhibit considerable self-reliance in tasks such as cooking, shopping, and personal grooming. This self-sufficiency is vital for their self-worth and psychological well-being, affecting their capacity to live independently, pursue education, and maintain employment (Pinkham et al., 2020; Odom et al., 2021).

Support networks and societal understanding play a crucial role in fostering autonomy. Research indicates that, with appropriate support systems in place, adults with autism can flourish and actively participate in various aspects of life. This support encompasses not only family assistance but also accessible healthcare services, employment opportunities, and social welfare programs tailored to the unique requirements of individuals with autism (Kilincaslan et al., 2019; Yau, Anderson, Smith, 2023). It is essential to acknowledge that the firsthand experiences shared by adults with autism offer invaluable insights into how society can better accommodate and support the autistic community. By attentively listening to these narratives, we can gain knowledge on how to establish environments that are genuinely inclusive and empowering individuals on the spectrum (Milner et al., 2019).

The experiences of autistic adults emphasize the importance of acknowledging their unique strengths and providing necessary assistance to enhance their independence. Family or community initiatives that offer tailored services play a crucial role in the overall well-being and achievements of autistic individuals in society (Beresford et al., 2020; Linden et al., 2022). Communication barriers are a critical aspect of the lived experiences of individuals in the autism spectrum. Autism symptoms can manifest in various ways and affect communication and social interactions. These challenges may include delays in response times, difficulties in maintaining eye contact, struggles in interpreting nonverbal cues, and participating in conversations. Individuals with autism often require more time to process information and formulate responses, leading to delays in their reactions during interactions. This slower response time might be misinterpreted by others, resulting in less frequent or less patient engagements (Pinkham et al., 2020; Huntjens et al., 2020).

The challenges related to the marriage of individuals with autism include various significant issues, such as difficulties in communication, concerns about having children with autism, and the impact of autism on marital stability and satisfaction. Communication difficulties are particularly pronounced for individuals with autism, as struggles in both verbal and nonverbal communication can pose significant barriers within relationships (Merriam, 2020). Challenges in interpreting body language, facial expressions, and social cues may lead to misunderstandings within a marriage. However, with appropriate support and understanding, many individuals with autism can develop successful relationships. Research indicates that individuals with autism can form lasting bonds and enter marriages (Pinkham et al., 2020).

Concerns about the possibility of having children with autism can heavily weigh on some individuals with autism. Studies have suggested that there may be a genetic predisposition for autism within families, increasing the likelihood of having an autistic child if there is a family history of the condition. However, it is crucial to acknowledge the potential for fulfilling family life (Huntjens et al., 2020; Jadav, Bal, 2022). Research on divorce rates among parents of autistic children presents mixed findings. Some studies suggest that these parents may experience increased stress levels and reduced marital satisfaction, potentially raising the risk of divorce. Conversely, other research indicates that having an autistic child does not necessarily lead to higher divorce rates compared to families without autistic members.

The severity of autism symptoms and the individual's level of functioning appear to significantly impact marital outcomes, with high-functioning individuals with autism potentially facing fewer relationship challenges (Hagner, Cooney, 2005). The complex impact of autism on marital satisfaction becomes evident when families raise a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). These families often grapple with heightened stress levels and decreased marital satisfaction. However, factors such as how partners perceive their relationship, the severity of autism symptoms in the child, and the duration of marriage all contribute to marital satisfaction (Huntjens et al., 2020; Jadav, Bal, 2022). In summary, while navigating marriage with autism presents its share of challenges, many individuals with autism lead happy and fulfilling married lives. It is essential for society to promote awareness, acceptance, and support for individuals with autism and their families as they successfully navigate these challenges (Maenner et al., 2021).

Autistic individuals face a range of complex challenges within the community that can significantly impact their quality of life. One of the main issues surrounding autism is the stigma and misunderstanding that can lead to social exclusion and discrimination. This stems from a lack of understanding and awareness of autism, which often results in fear and anxiety among the public when interacting with individuals who have autism. However, efforts to increase public awareness have yielded positive outcomes, including increased acceptance and support for individuals with autism (Han et al., 2022; Linden et al., 2022). Additionally, many individuals with autism find comfort and stability in adhering to routines, which can help alleviate their anxiety. However, excessive attachment to routines may present challenges for social interactions and adaptability. Therefore, it is crucial to strike a balance between routine engagement and social engagement (Lerner et al., 2025).

The challenge of forming friendships is another significant obstacle for individuals with autism because of the difficulties in understanding social norms and nonverbal communication. While some individuals with mild autism can establish and maintain friendships, others may prefer familiar acquaintances to new connections. Social media has emerged as a platform that provides meaningful friendships for adolescents with autism by providing a less stressful environment for social interactions. It serves as a comfortable medium for communication, particularly among those who experience anxiety during face-to-face interactions (Grzadzinski et al., 2021). A prevalent issue is the tendency to underestimate the abilities and talents of youths with autism, often stemming from misconceptions about their capabilities. This lack of trust can hinder the acceptance of innovative treatment approaches and limit the opportunities for individuals with autism to showcase their potential. Access to specialized autism services and interventions is crucial for meeting the needs of individuals with autism; however, limited resources and dedicated centers often restrict the availability of effective interventions and support (Grzadzinski et al., 2021; Weston, Hodgekins, Langdon, 2016).

In conclusion, individuals on the autism spectrum face significant obstacles in their communities; nevertheless, studies indicate that enhancing awareness, fostering understanding, and providing adequate resources can greatly alleviate these challenges. Continuous advocacy for the rights and needs of autistic individuals is vital for enabling them to lead fulfilling lives within their communities (Lerner et al., 2025; Grzadzinski et al., 2021). Additionally, adults with autism have underscored the importance of family support in the growth of autistic youth. Research suggests that early involvement and assistance from family members can lead to positive outcomes for those with autism. Conversely, insufficient familial support may hinder the acquisition of crucial adaptive skills. It is important to recognize that while financial assistance is valuable, emotional and educational support is equally essential (Grzadzinski et al., 2021).

Furthermore, the roles of educators and caregivers are essential to the progress of youth with autism. Demonstrating patience and understanding can significantly influence the learning path and overall growth of these individuals. Providing teachers and caregivers with suitable training to increase their understanding of autism can establish supportive learning settings. However, a differing opinion suggests that an excessive focus on patience might lead to reduced expectations and restrict the autonomy of individuals with autism (Weston, Hodgekins, Langdon, 2016).

Ultimately, it is essential for the governorate to allocate resources and provide support, including financial investments and comprehensive rehabilitation programs, to ensure the well-being of individuals with autism. This support can enable these individuals to engage productively within society. However, another perspective suggests that government assistance should extend beyond mere financial aid to encompass the development of inclusive policies and environments that cater to the varied needs of those with autism (Smith DaWalt et al., 2019).

Limitations

This study represents one of the first explorations into the lived experiences and perspectives of autistic adults in Saudi Arabia a topic that remains largely under-researched both regionally and globally. By giving voice to this often-overlooked population, the study offers meaningful insights into their strengths, daily life challenges, communication barriers, and views on romantic relationships and independence. Despite its pioneering nature, several limitations should be acknowledged. Initially, it was carried out in just one region of Saudi Arabia, which could restrict the applicability of the results to different cultural or geographical settings. Secondly, the number of autistic adult participants was rather limited (n = 7), which constrains the range of viewpoints and might not completely reflect the variety within the autistic adult community. Third, although thorough efforts were undertaken to establish suitable inclusion criteria, there might have been some uncertainty or inconsistency in their interpretation or application because of dependence on center records and guardian consent protocols. Moreover, the characteristics of autism and related intellectual disabilities may have impacted the richness and lucidity of responses, even though the focus group guide was modified for accessibility. Finally, the likelihood of social desirability bias could have influenced the answers of participants, especially in group situations.

Conclusion

The research underscores the distinctive advantages and ongoing obstacles encountered by autistic adults as they strive for independence and meaningful connections. Although individuals on the autism spectrum demonstrate exceptional skills in certain domains, such as adherence to routines and specialized expertise, they face considerable challenges, including societal stigma, insufficient support systems, and a lack of resources. This study emphasizes the essential contributions of family, community, and governmental assistance in facilitating the autonomy of autistic adults and fostering their ability to cultivate successful interpersonal relationships.

Future Research

Future research should focus on incorporating larger and more varied samples from different areas to improve the generalizability of insights concerning the experiences of autistic adults. Studies utilizing longitudinal designs would offer greater understanding of how skills, connections, and difficulties develop over time. Moreover, upcoming research could investigate the viewpoints of autistic adults with different functioning levels, including individuals who might be unable to engage in group discussions, by employing other qualitative approaches like personal interviews or observational research. Examining the impact of customized interventions to aid independent living and romantic relationships for autistic adults across various cultural settings would also be beneficial. Ultimately, enhanced cooperation with autistic individuals in the creation and execution of research might boost relevance and inclusivity.

Implications

Based on the study results the following implications could be suggested:

- Conducting educational campaigns that aim to highlight the strengths and requirements of autistic individuals, thereby facilitating their acceptance and integration within the community.

- It is essential to improve societal knowledge regarding autism to mitigate stigma and encourage inclusivity.

- The provision of specialized services, including vocational training, social skills enhancement, and mental health resources, is vital for empowering autistic adults towards self-sufficiency. These programs must be readily available and tailored to address the unique needs of this demographic.

- Governments play a crucial role in the support of autistic adults by offering financial assistance and investing in resources that foster independence.

- Establishment of more specialized centers for adult transition, enhancement training for healthcare professionals working with autistic individuals, and formulating inclusive policies that guarantee equal opportunities across various life domains.

Recommendations

According to the study findings, following recommendations were made:

- Conducting public awareness campaigns about Autism. They should be efforts to destigmatize and normalize autism, as well as promote autistics in their environments of habitation.

- Establish More Specialized Services: Governments should provide more funding to create specialized centers where autistic people can get help with transitioning into adulthood. A must-have for such centers that offer vocational training, independent living skills and social engagement programs.

- Offer More in-service Training to Care Providers: Designation more, In-employees training courses for the Hospital Personnel that work with adults along with Autism. Some of this education should include an appreciation for the different needs and solutions that are required to support independence, safety and well-being in those situations.

- Policy Advocate for the creation of policies which respect the rights and require autism62, software. These efforts range from providing inclusive education and accessibility in the workplace to comprehensive community offerings tailored around their individual needs.

- Support for Marital Relationships: Create resources and programs which can help autistic individuals to navigate romantic relationships, dating or marriage. Accordingly, counseling and communication services should be tailored for autistic adults facing challenges in those areas.

By addressing these recommendations, society can better support autistic adults in their journey toward independence and fulfilling relationships, ultimately improving their quality of life.

1 https://aaspire.org/research/interview-guidelines