Introduction

Most modern researchers note significant changes taking place in the processes that accompany the growing up of today's youth around the world [Litvinova, 2020; Shilova, 2021; Ayotte; Boisvert; Shanahan, 2000; Zukauskiene, 2016]. It becomes clear that growing up is a complex, multifaceted process that covers a significant part of a person's life and is influenced by historical time. As N. N. Tolstykh notes, the questions with which we should start discussing the problem of modern growing up are questions about the age at which a person can be considered an adult, the requirements of society for an adult and internal criteria—‘on the basis of what does a growing person begin to consider themselves an adult?’ [Tolstykh, 2015, p. 8]. Thus, we are talking about the selection of chronological, sociocultural and psychological markers of adulthood, which are only partially interconnected and exposed to heterochrony, which has been increasing in recent years. For example, recent demographic studies show that the age at which partnerships are initiated has fallen to historic lows, while the age at which education is completed has increased significantly. Young people ‘debut in different spheres of life by their life schedules and at the right time’ [Mitrofanova, 2020, p. 36], which probably occurs as a result of the weakening of traditions, increasing informatisation and individualisation of modern society. This socio-demographic context determines the relevance of research into the maturation of young people.

In each of the identified aspects of growing up, serious transformations have taken place in recent decades. Chronological markers of adulthood have expanded significantly [Tolstykh, 2015; Shilova, 2021; Arnett; Zukauskiene, 2016]. For the last 20 years, we have been using J. Arnett's term ‘emerging adulthood’ in relation to young people from 18 to 30 years old [Arnett], suggesting that even by the age of 30, not everyone makes the transition to adulthood, which is especially the characteristic of developed industrial societies that allow a long education and period of searching for one's own identity through trials and experiments.

The traditional social and role markers of entering adulthood, which were such events as graduation, leaving the parental family, marital status, the appearance of the first child, making a decision about the future profession, stable employment and financial independence, are also losing their role [Shanahan, 2000; Zukauskiene, 2016]. Several authors note that the internal, psychological criteria of adulthood prevail in importance over social ones [Arnett; Zukauskiene, 2016; Zukauskienė], however, this thesis strongly depends on the demographic context and socioeconomic status of the studied group of young people [Shilova, 2021; Arnett; Boisvert] that indicate the heterogeneity and high individualisation of the process of transition to adulthood.

The psychological criteria of adulthood are associated with the formation of autonomy, beginning of self-realisation, growth of responsibility, individualisation, stress resistance and realism. This allows us to define growing up as the acquisition of the qualities of personal maturity—responsibility, autonomy, resilience, focus on self-development and self-understanding [Litvinova, 2020; Psikhologicheskaya zrelost’ lichnosti, 2014]. Most of these qualities also correspond to the concept of psychological well-being which includes personal characteristics of positive functioning [Malenova, 2020].

The most important psychological criterion for the transition to adulthood is subjective adulthood or a formed ‘adult’ identity that allows one to classify oneself as a member of the adult world and subculture [Polivanova, 2000]. Subjective adulthood begins to form already in adolescence as a ‘sense of adulthood’—the main neoplasm of this period, including the adolescents’ attitude to themselves as an adult, their idea or feeling of being an adult, which in adolescence is not always conscious, but is already included in the design of the image of adulthood [Polivanova, 2000], thereby contributing to real maturation. In the study of M. V. Klementieva, it is shown that in the period of 18–33 years, the age transition from diffusion to integration and connectivity of the ‘true self’ and the ‘adult self’ is still taking place when a person manages to harmoniously balance their authenticity and the social expectations from society [Klement’eva, 2020]. It has been shown that at the stage of emerging adulthood, the feeling of adulthood is unstable and grows with an increase in the stressful fullness of life [Bellingtier].

The growing differentiation of maturation and the difficulty of identifying markers of its achievement raise the question of the mechanisms of the emergence of adulthood. In the context of growing up as the formation of one's individuality and gaining spatial, functional and psychological autonomy, the most important mechanism is psychological separation from parents [Dzukaeva, 2016; Litvinova, 2020; Malenova, 2020; Petrenko, 2016; Tikhomirova; Kharlamenkova, 2019; Sugimura]. Timely separation of a child from parents is associated with the development of the ability to control, protect and develop one’s psychological space [Nartova-Bochaver, 2011] corresponds to the formation of responsibility, setting life goals, entering an independent life, maturity and subjectivity [Litvinova, 2020; Tikhomirova; Sugimura]. This is a long-term process of mental separation of the child from their parents and family, accompanied by the development of identity, which starts at an early age and continues in adulthood [Tikhomirova; Kharlamenkova, 2019; Sugimura]. T. V. Petrenko and L. V. Sysoeva note that at the age of 23–25 years, separation activity increases significantly—this is a turning point in confrontation, the final separation from parents and the beginning of independent life [Petrenko, 2016]. N. E. Kharlamenkova highlights the external and internal sides of separation where the first involves separation, severance of relations, distancing, getting rid of external control along with the adoption of responsible decisions and the manifestation of independence. Internal separation is the separation of the Self from internal objects and the present—from images of the past and future when a person is separated from previous feelings, actions and ways of thinking that do not correspond to new life tasks [Kharlamenkova, 2019]. In the structural model of J. Hoffman, separation is considered on three levels: emotional (as a decrease in the need for parental approval and support); attitude (cognitive) as the formation of views and judgments different from parental ones and the ability to build a position based on one's own experience; functional (behavioural), the ability to make independent decisions, solve problems, the ability to provide for oneself on one's own. An idea about the style of separation is introduced (harmonious or conflict), associated with the manifestation of negative feelings of guilt, anger, anxiety and distrust arising in the process of separation [Dzukaeva, 2016; Hoffman, 1984]. Studies also record the gender specifics of separation from parents and differences in models of separation from the father and mother [Dzukaeva, 2016; Tikhomirova; Kavcic].

The complex structure of separation suggests that it is precisely the features of its course—the ratio of the external and internal sides, as well as various components that determine the process of becoming an adult both in terms of its external social and role criteria (spatial, financial independence, independence in everyday life and building relationships), and internal, psychological that are associated with the formation of maturity and adult identity. Indirect criteria that determine the course of growing up, indicating the degree of maturity of the individual and the success of solving age-related tasks may be the psychological well-being of the individual in conjunction with their emotional characteristics, happiness and satisfaction. The consideration of separation as a complex set of processes that ensure growing up determines the novelty of this approach to the study of youth maturation.

Thus, based on the foregoing, the purpose of the study was formulated to determine the role of psychological separation from parents in the formation of adult identity and in ensuring the psychological well-being of young adults.

The hypothesis is based on the following assumptions:

1. Psychological separation is a heterogeneous phenomenon where the components of psychological separation from the father and mother have different severity and are differently related to the formation of an adult's identity (subjective adulthood) and the psychological well-being of a young person.

2. The severity of separation processes and the formation of an adult's identity are interconnected with the psychological well-being of young adults due to the importance of this process in a given age period.

To achieve the purpose of the study and test the hypotheses, the following tasks were formulated: 1) to study separation from parents in the ratio of its various components: spatial separation, financial independence, household independence (functional aspect) and psychological components of separation from the father and mother, taking into account gender specifics and chronological age of respondents; 2) to study the formation of an adult identity (subjective adulthood) and its foundations; 3) to study the relationship of separation and psychological well-being with the formation of an adult identity; 4) to assess the impact of the components of psychological separation from parents on indicators of psychological well-being.

Methods

Measures. To study psychological separation from parents, the Psychological Separation Inventory by J. Hoffman Q (PSI) [Hoffman, 1984], adapted by T. Yu. Sadovnikova and V. P. Dzukaeva, was used [Dzukaeva, 2016; Malenova, 2020]. Scales: ‘Conflictual Separation’ (Style), ‘Emotional Separation’, ‘Attitudinal Separation’ (Cognitive) and ‘Functional Separation’ (Behavioural), measured separately for the father and mother on a 5-point Likert scale. The characteristics of the scales correspond to the structural model of J. Hoffman presented in the introduction.

The study of functional separation included an assessment of cohabitation or separation from parents (spatial aspect); assessment of self-dependence in everyday life and the formation of the necessary life skills (cooking, cleaning living space, paying bills, making necessary household and large purchases, communication with government agencies, etc.), measured on a 4-point scale; assessment of financial independence.

To study subjective adulthood, respondents were asked an open question: ‘Do you consider yourself an adult? Why?’, which also made it possible to describe the criteria by which young people classify themselves or do not classify themselves as adults.

To study psychological well-being, we used the C. Riff Scale adapted by L. V. Zhukovskaya and E. G. Troshikhina [Psikhoemotsional’noe blagopoluchie: integrativnyi, 2020]. Scales: ‘Autonomy’, ‘Environmental mastery’, ‘Personal Growth’, ‘Positive Relations with other people’, ‘Purpose in Life’ (sense of meaningfulness and direction of one's existence), ‘Self-acceptance’, ‘General indicator of psychological well-being’, measured on a 5-point Likert scale.

To measure the emotional aspects of well-being, the E. Diener Life Satisfaction Scale adapted by D. A. Leontieva and E. N. Osin, as well as M. Fordis Happiness Scale were used [Psikhoemotsional’noe blagopoluchie: integrativnyi, 2020].

The selected methods are widely used in world practice [Dzukaeva, 2016; Litvinova, 2020; Malenova, 2020; Psikhoemotsional’noe blagopoluchie: integrativnyi, 2020; Boisvert; Hoffman, 1984; Kavcic; Zukauskienė], which makes it possible to compare the results of various studies.

Participants. The study involved 126 people living in St. Petersburg (50 men, 76 women), aged 18–27 years (M = 22.3; SD = 2.1). Students made up 44% of the sample, adults who combine work and study were 15.3% of the sample, working adults were 33.5% and about 7% of the sample were other possible options (including unemployed). The sample was formed randomly, taking into account the age range of the period of emerging adulthood and a relatively even distribution by gender; anonymously and voluntarily. The survey was conducted in an online format, the participants received feedback at will.

Statistics: frequency analysis; descriptive statistics; comparative analysis by using Student's t-test for dependent and independent samples, one-way analysis of variance ANOVA; correlation analysis (Pearson's test); regression analysis; content analysis.

Results

Separation from parents. Indicators of functional separation indicate its formation as a whole. Spatial separation: 25.8% of the sample live with their parents and the rest of the young people live in a separate apartment, hostel, with partners, friends or relatives. The average age at which young people leave their parental home was 19 years old and ranged from 15 to 24 years. The financial independence of young people is also quite high: 68% of the sample are fully or almost completely self-sufficient, 15% partially earn on their own, but still use their parents' money, another 10% are supported by partners and only 6% of young people are fully supported by their parents. For 74% of the sample, the first experience of paid activity is quite early and falls during the period of 14–17 years, extending further up to 23 years. Household self-dependence as a whole is also fully formed (M = 3.03; SD = 0.59) and is subject to gender specificity—women more often show household self-dependence according to several indicators. This concerns making daily purchases, cleaning living space (p ≤ 0.001), visiting medical facilities and leisure planning (p ≤ 0.05), which ultimately affects the higher overall self-reliance in women (p ≤ 0.05).

Analysis of the average values for indicators of psychological separation reveals a tendency for greater severity of indicators of psychological separation from the father compared to a mother, regardless of gender (Table 1). This difference is highly significant for all scales, except for the separation style (p < 0.001, t-test for dependent samples)—young people are significantly more in need of emotional support and approval from their mother than from their father, showing greater similarity with their mother's ideas and worldviews when making important decisions, more often need a mother's advice than father's. The general trend is also the predominance of the behavioural component of separation for the sample as a whole.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics on the scales of the Psychological Separation Inventory

|

Scales |

The whole sample |

М Male |

М Female |

t-test |

|

|

М |

SD |

||||

|

Conflictual Separation (mother) |

3.67 |

0.71 |

3.91 |

3.50 |

3.26** |

|

Conflictual Separation (father) |

3.80 |

0.77 |

3.91 |

3.75 |

1.13 |

|

Emotional Separation (mother) |

3.56 |

0.85 |

3.73 |

3.46 |

1.76 |

|

Emotional Separation (father) |

4.04 |

0.94 |

4.16 |

3.97 |

1.04 |

|

Attitudinal Separation (mother) |

3.56 |

0.87 |

3.67 |

3.48 |

1.19 |

|

Attitudinal Separation (father) |

3.86 |

0.95 |

4.00 |

3.78 |

1,19 |

|

Functional Separation (mother) |

4.03 |

0.75 |

4.27 |

3.86 |

3.05* |

|

Functional Separation (father) |

4.38 |

0.79 |

4.37 |

4.38 |

–0.75 |

Note: * –р ≤ 0.05; **–р ≤ 0.01.

Gender differences were found on the scales ‘Conflictual Separation (mother)’ and ‘Functional Separation (mother)’ and indicate that men are easier and more harmonious separate from their mothers than women, and are also more independent of their mothers in making important decisions and in their life choices (Table 1).

The correlation coefficient for dependent samples showed the relationship between identical separation scales (0.358 ≤ r ≤ 0.570; p < 0.001), which together with the absence of significant differences on the ‘Conflictual Separation’ scale from the father and mother, indicates the unidirectional and consistent nature of the separation from the parental couple.

Correlation analysis (Pearson's criterion) revealed most of the separation components tend to increase with age (except for the emotional separation component from father and mother). The closest relationship with age is found in the attitudinal separation from the father (r = 0.266; p = 0.005) and the functional separation from the mother (r = 0.264; p = 0.003), i.e. there is a tendency to increase differences in views and judgments with fathers and the ability to act without relying on the effective help of a mother, but the need for emotional support and approval of parents does not decrease with age.

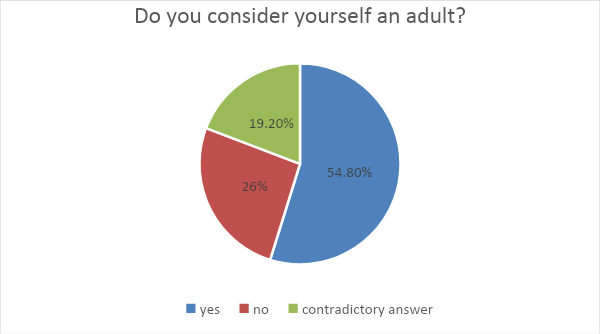

Subjective adulthood and its foundations. This aspect was studied using content analysis of answers to the question of whether young people consider themselves adults and why. The distribution of answers showed that more than half of the sample (54.8%) have an adult identity formed (consider themselves adults), a quarter of the sample (26%) have no adult identity (do not consider themselves adults), a fifth of the sample has doubts and gives contradictory answers (19.2%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Distribution of answers to the question about subjective adulthood

Next, the criteria based on which the respondents classified (or did not classify) themselves as adults were analysed. Two categories (external/internal criteria of adulthood) and 7 subcategories were selected (Table 2). Such a division of categories and subcategories as external and internal is based on the widespread analysis of the criteria of adulthood in modern studies [Arnett; Ayotte; Boisvert; Zukauskienė].

Table 2

Distribution of respondents' answers regarding the criteria of adulthood they single out

|

Categories |

Subcategories |

% sample |

|

External criteria of adulthood |

Financial security (independence) |

19 |

|

Separate accommodation |

10 |

|

|

Occupation (studies or works) |

5 |

|

|

Total by external criteria |

34 |

|

|

Internal criteria of adulthood |

Responsibility |

32 |

|

Self-dependence |

27 |

|

|

Psychological qualities of personal maturity (‘self-sufficiency’, self-confidence, ‘reliance on life experience’, caring for close people, etc.) |

22 |

|

|

Stability |

5 |

|

|

|

Total by internal criteria |

86 |

|

Other (no answer, joke answer, etc.) |

15 |

|

The results showed that internal and psychological criteria of adulthood are the predominant grounds for adulthood (the share of their references was 86%, while external ones—only 34%), with responsibility (32%) and independence (27%) occupying leading positions. The most significant external criterion is financial independence (19%), but the importance of employment as a criterion of adulthood is the least (5%).

Connection of psychological separation, subjective adulthood and psychological well-being. By using ANOVA, the differences in psychological separation and psychological well-being in groups with different adult identity formations were studied. There were no significant differences in separation parameters, i.e. subjective adulthood is not related to the degree of psychological separation from parents. The chronological age of young people in groups with different subjective maturity did not differ either. Significant differences were found in the parameters of psychological well-being (Table 3).

Table 3

Indicators of psychological well-being in groups with different formations of adult identity (significant differences)

|

Indicators |

Do not consider themselves adults |

Consider themselves adults |

Doubters |

F |

p-level |

|

Environmental mastery |

25.84* |

32.09* |

30.36 |

8.244 |

0.001 |

|

Purpose in life |

27.42* |

35.05* |

33.14* |

9.342 |

0.000 |

|

Self-acceptance |

29.05* |

34.86* |

34.07 |

4.981 |

0.009 |

|

General well-being |

181.53* |

204,02* |

201.5 |

5.701 |

0.005 |

|

Satisfaction with life |

3.05* |

4.19* |

4.00 |

4.097 |

0.021 |

Note: an asterisk (*) indicates groups that differ significantly from each other in terms of the results applying the Scheffe correction.

Young people with a developed adult identity have a greater sense of competence in mastering the environment (‘Environmental mastery’), are more accepting of various aspects of their personality (‘Self-acceptance’), and are generally more prosperous (‘General well-being’) compared to those who have not formed an adult identity. According to the ‘Purpose in life’ scale, each of the selected groups differs significantly from each other, and respondents with an unformed sense of adulthood feel a lack goals, direction and meaning in life. Satisfaction with life is also significantly higher in the group with a formed adult identity. Also, the group of subjective adulthood has more experience (0.5 years on average) of living separately (F = 3.948; p = 0.02).

The impact of psychological separation components from parents on the psychological well-being of young adults. To solve this problem, multiple regression analysis was used, where the independent variables were the scales of psychological separation from parents, and the dependent variables were the parameters of psychological well-being. In Table 4, the results are presented in order of decreasing dispersion of the models.

Table 4

Results of regression analysis

|

Dependent variables |

R-square |

Predictors |

Beta |

р-level |

|

Satisfaction with life (Diener) |

0.50 |

Conflictual separation (father) |

0,391 |

0.001 |

|

Functional separation (father) |

–0.431 |

0.002 |

||

|

Happiness frequency (Fordis) |

0.26 |

Conflictual separation (father) |

0.420 |

0.001 |

|

Functional Separation (mother) |

–0.384 |

0.002 |

||

|

Purpose in life (Riff) |

0.14 |

Functional separation (father) |

–0.368 |

0.004 |

|

Positive relations (Riff) |

0.12 |

Conflictual Separation (mother) |

0.348 |

0.007 |

The style of separation (‘Conflictual separation’) from the father is a positive predictor of life satisfaction and the frequency of experiencing happiness. The style of separation from the mother is a positive predictor of the ‘Positive relations’ component—harmonious separation has an affirmative effect on subjective well-being.

At the same time, the growth of ‘Functional separation’ from parents negatively affects life satisfaction and happiness. The back impact of the behavioural component of separation from the father on the ‘Purpose in life’ criterion shows that a decrease of orientation to the father's help and independent decision-making can lead to a loss of a sense of direction in life.

Conclusions and Discussion

The results of the study confirm our hypothesis about separation as a heterogeneous phenomenon. It is shown that the behavioural and functional aspects of separation are more pronounced than the emotional and cognitive components in the period of emerging adulthood. This partially correlates with the results of the studies of separation in adolescence [Dzukaeva, 2016; Petrenko, 2016]. So, we can assume that the external separation, which markers are the behavioural and functional aspects associated with the ability to make decisions independently, make choices, the ability to self-service, spatial separation and financial independence, leads to an internal separation associated with the formation of identity and personal maturity.

Separation from the father is generally more pronounced than separation from a mother, but it is more difficult for girls to separate from their mothers. The separation of a child in a family is unidirectional, i.e. moving away from one parent is not compensated by moving closer to the other.

During emerging adulthood, separation indicators grow, however, the absence of a connection between age and affective components of separation allows us to speak of the need for emotional support and parental approval that persists during this period. Probably, emotional separation from parents is formed most late, outside of early adulthood, which confirms the assumption of N. E. Kharlamenkova on the continuation of separation processes in adulthood [Kharlamenkova, 2019], and is also consistent with some empirical studies of separation in adulthood [Tikhomirova].

Subjective adulthood is not associated with the degree of separation from parents and chronological age but is associated with psychological well-being. Apparently, the growth of self-acceptance, mastery in managing the environment, acquisition of the direction and meaning in one's own life and a general sense of stability and satisfaction with life are the sources of the formation of an adult identity. It can also be assumed that the connection between separation and subjective adulthood is mediated by psychological well-being, and separation itself does not lead to a sense of being an adult. This is consistent with the fact that the criteria for adulthood for young people are mostly internal and psychological, where responsibility and independence are the main markers, and the most significant external criterion is financial independence. These results correspond to some results of foreign studies [Arnett; Ayotte; Boisvert; Zukauskienė].

Regarding the influence of the components of psychological separation on well-being, the study showed that the behavioural components of separation are predictors of a decrease in satisfaction, happiness and purposefulness of life. Independence in decision-making and making choices still hinders the experience of emotional well-being, which is probably associated with an increase in the number of life difficulties and growth of responsibility. A harmonious (conflict-free) style of separation from parents, on the contrary, contributes to the rising of life satisfaction and happiness. Similar results were obtained in one of the modern cross-cultural studies on emerging adulthood [Sugimura].

In general, the obtained results indicate that separation, especially external separation, is a painful and difficult process for a young adult, however, overcoming these difficulties leads to an increase in psychological well-being and formation of subjective adulthood, and therefore contributes to maturation.

At the same time, it should be noted that the measurement of subjective adulthood as a qualitative characteristic in our study acts as its limitation as the results obtained could not be included in the regression analysis to assess their impact on psychological well-being. In future research, attention should be paid to the development of numerical scales for measuring subjective adulthood. In addition, the most perspective direction in studying the relationship between separation features and maturation processes is longitudinal studies covering the entire period of emerging adulthood, as well as a two-sided study of separation processes in parent–adult child dyads.