Introduction

Do students use their phones for personal purposes during class? How has this usage been influenced by recent changes to the Federal Law on Education in the Russian Federation? Is cyberloafing connected to other forms of Internet deviance? These questions are crucial for an education system that is actively cultivating a digital learning environment. The answers will help us evaluate the potential benefits and risks associated with the introduction of digital communication technologies in our lives.

It is hard to envision the modern world without information technologies, which have already become integral to the lives of every generation, particularly children and youth. These technologies have also established their place in the educational realm. However, the key question remains: How appropriately are students utilizing these tools? Improper use of gadgets can lead to the development of various issues related to virtual space, such as cyberloafing and cyberbullying. The characteristics of both behaviors have been documented. Data has been collected from various countries regarding the prevalence of cyberloafing and cyberbullying across different age groups. Nonetheless, the correlation between these forms of deviance has yet to be examined.

In this article, we explore the prevalence of cyberloafing and cyberbullying among Russian schoolchildren and students, particularly in light of revisions to the Federal Law 'On Education in the Russian Federation.' This law alters the status of cyberloafing, enabling it to be classified as delinquent behavior. Furthermore, we investigate the relationships between cyberloafing and cyberbullying, which hold both theoretical and practical significance.

Cyberloafing refers to the use of digital devices during work or study to attend to tasks that are unrelated to those obligations. It manifests in various ways. Depending on the context, one can identify business cyberloafing, academic cyberloafing, and phubbing. The first pertains to behavior in the workplace, the second to behavior during educational sessions, and the third to behavior in interpersonal interactions. The rise of academic cyberloafing is tied to the digitalization of education.

Australian researcher S. Nawaz highlights the importance of distinguishing between effective, ineffective, and problematic smartphone usage in today's context. This differentiation is significant when considering the nature of cyberloafing—whether it is a form of deviant or proactive behavior.

When framed as deviant behavior, cyberloafing is discussed as being rooted in phone dependency or cyber addiction, often referred to as problematic smartphone use. There is also a substantial argument for viewing cyberloafing as a form of delinquent behavior due to ineffective smartphone usage. Some researchers characterize cyberloafing as a defensive response to stress or perceived injustice.

Understanding the structure of cyberloafing is critical. It consists of a range of behaviors derived from the content of a user's online activities. The two-factor model proposed by V.K.G. Lim identifies two types of cyberloafing behavior: Internet surfing and email usage. A three-factor model by M.H. Baturay and S. Toker differentiates behaviors related to personal activities, news consumption, and socialization. Additionally, Turkish researchers have outlined a five-factor model encompassing interaction, online shopping, web presence, content usage, and gaming.

Engaging with virtual spaces comes with the risk of deviant behavior, including an increase in aggression. Recently, there has been a surge in incidents of bullying online, termed cyberbullying. This phenomenon consists of deliberate actions aimed at psychologically harming victims through electronic communication channels. Cyberbullying is inherently a group phenomenon, characterized by systemic violence directed at one individual, which evolves over time.

A crucial aspect of cyberbullying research is understanding its role structure. The simplest model comprises the victim, the aggressor, and the witnesses. A more intricate model includes roles such as the victim, the aggressor, the victim's defenders, the aggressor's helpers, and passive observers. A single individual can occupy different roles over time, acting as an aggressor in one scenario and a victim in another. G.U. Soldatova's findings support this idea, revealing that the personality traits of cyberbullying victims and aggressors share common characteristics.

Utilizing the 'situation-organism-behavior-consequences' model proposed by researchers in the UAE allows for a chain of reasoning: If a student feels bored during class, they may seek to fulfill needs for self-actualization, communication, and entertainment through their phones. Consequently, they may use smartphones to access the web or find interesting information, leading to cyberloafing. This behavior can create risks associated with information and communication overload, which in turn can give rise to destructive behaviors such as cyberbullying. Therefore, a relationship between cyberbullying and cyberloafing can be inferred.

In conclusion, the phenomena of cyberloafing and cyberbullying are being examined by researchers worldwide. However, whether a connection exists between them has not yet been investigated. Therefore, we have formulated the following research hypotheses:

- The level of cyberloafing depends on gender, level of education, and banning the use of phones in educational institutions.

- Involvement in cyberbullying depends on gender and level of education.

- There is a relationship between involvement in cyberbullying and level of cyberloafing.

Organization and methods of the study

Study Sample: The research was conducted at South Ural State Humanitarian-Pedagogical University in Chelyabinsk, involving a total of 344 participants. The respondents' ages ranged from 14 to 22 years. Among these, 128 were schoolchildren aged 14-18 years, attending general education schools in Chelyabinsk (7th to 11th grades). Of this group, 48% were male and 52% were female. The remaining 216 participants were university students aged 17-22 years (first to fourth year). In this group, 43% were male and 57% were female. The database used for this study is registered with the Federal Service for Intellectual Property (Certificate of State Registration of Database No. 2024625767).

Research Methods: The data collection methods employed included the Cyberbullying Scale, adapted by N.V. Sivrikova, and the School Bullying Questionnaire developed by M.A. Novikova et al. (only the Cyberbullying Scale was utilized in this study). The authors of these methods do not present normative values, focusing instead on the frequency of specific answers to the questions. They explain that representing respondents' involvement in bullying as percentages allows for comparison across different studies, aligning with how this category is described in the literature. The full texts of the methodologies are available in the authors' previous works.

Additionally, the questionnaire included demographic questions related to the respondents' gender, age, and level of education. The study was conducted in an online format, gathering a total of 368 completed questionnaires. Out of these, 344 were deemed valid for further analysis, while 24 were excluded due to incomplete responses.

In light of new amendments to the Law on Education that will take effect in January 2024, the survey included the question: 'Does your school/university have a rule prohibiting the use of phones during classes?'

We assessed the distribution parameters of the studied features within the sample population to ensure the appropriate selection of mathematical data analysis methods. The parameter values for the entire sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Statistical characteristics of the distribution of the studied features in the empirical sample

|

Researched parameters |

Kolmogorov-Smirnov Z |

p |

М |

SD |

Asymmetry |

Excess |

|

|

Structure of cyberloafing |

|

||||||

|

Communication |

0.143 |

0.0001 |

1.9 |

0.88 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

|

|

Online shopping |

0.19 |

0.0001 |

1.7 |

0.81 |

1.3 |

1.6 |

|

|

Content |

0.18 |

0.0001 |

2.0 |

0.98 |

1.0 |

0.1 |

|

|

Games |

0.22 |

0.0001 |

1.7 |

0.88 |

1.4 |

1.21 |

|

|

Social networks |

0.17 |

0.0001 |

1.8 |

0.88 |

1.3 |

1.58 |

|

|

Cyberloafing |

0.14 |

0.0001 |

1.8 |

0.78 |

1.2 |

1.5 |

|

|

Structure of cyberbullying |

|

||||||

|

Victim role |

0.43 |

0.0001 |

1.15 |

0.38 |

3.6 |

15.7 |

|

|

Aggressor role |

0.43 |

0.0001 |

1.13 |

0.33 |

3.4 |

13.8 |

|

|

Witness role |

0.43 |

0.0001 |

1.15 |

0.31 |

2.4 |

5.3 |

|

The characteristics of the empirical distribution of the studied variables differ from those of a normal distribution. Specifically, the skewness and kurtosis values fall outside the range of -1 to 1, and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test confirmed the primary hypothesis (p < 0.001). This pattern was consistent when analyzing subgroups of students and schoolchildren.

Consequently, we employed non-parametric methods to identify relationships between the studied variables. These methods included Spearman correlation analysis, Kruskal-Wallis H-criterion, and Fisher's exact test. We also utilized CHAID analysis during the study. Calculations were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.

Study results

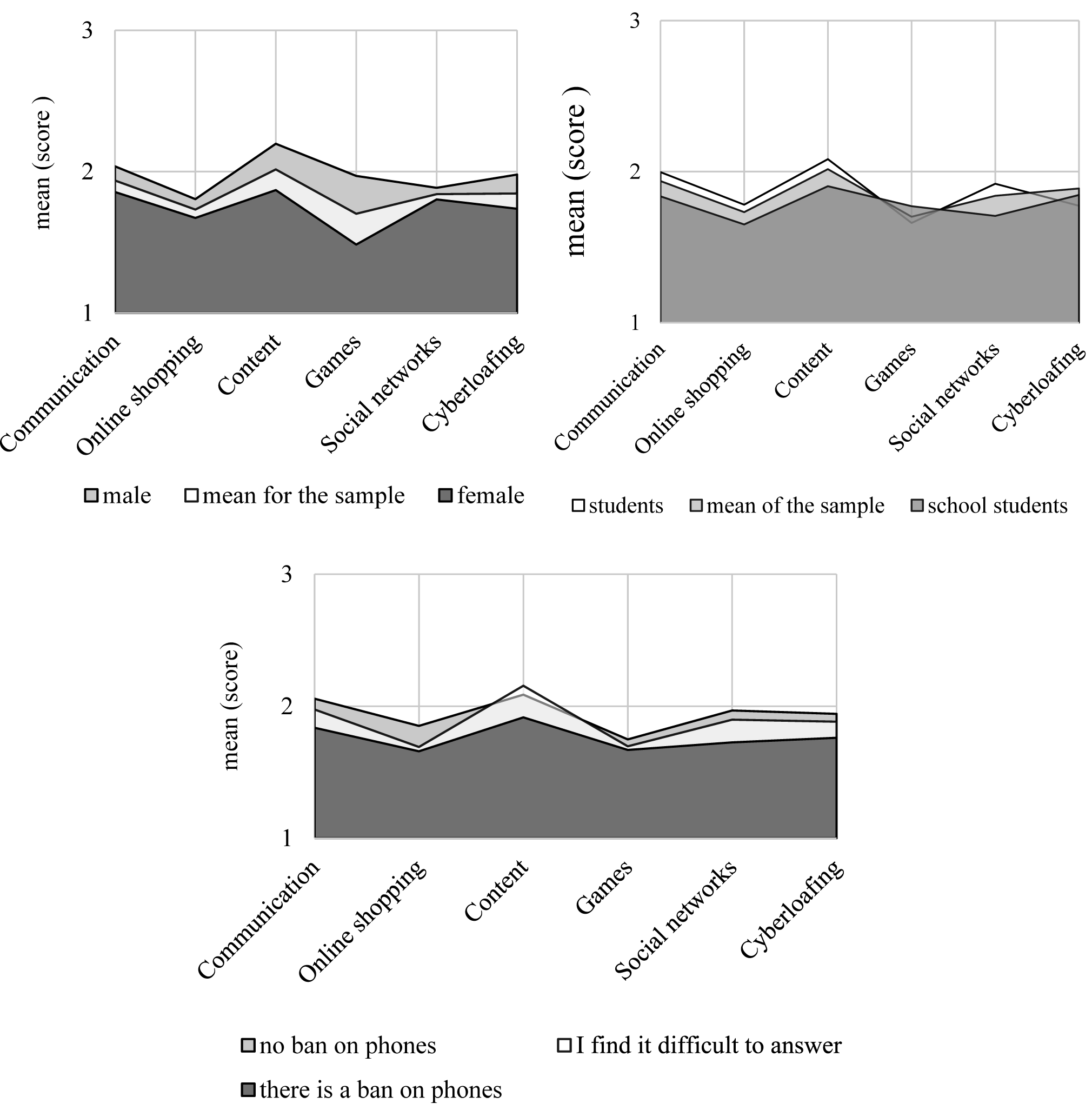

The survey results showed that the level of cyberloafing in the study sample is quite low (Fig. 1).

According to the group average, cyberloafing is rarely used by the study participants (M=2). At the same time, the structure of cyberloafing has its own peculiarities depending on gender and level of education, and the level of cyberloafing depends on the presence of a ban on phone use in the educational institution.

In the cyberloafing patterns of female study participants, gaming cyberloafing is the rarest, while the most frequent forms of cyberloafing include communication, content use, and social networking. The pattern of cyberloafing among boys is dominated by the use of Internet content and socializing in classrooms. Less pronounced forms of cyberloafing among boys are Internet shopping. Differences were found in the level of cyberloafing in boys and girls (N=5.82; p=0.016).

Figure 1. Types and levels of cyberloafing

The predominant types of cyberloafing among students are socializing, content use, and social networking. The least common types of cyberloafing among them are gaming cyberloafing. For students, the most common types of cyberloafing include communication and use of Internet content. They are least likely to use social media and gaming in lessons. According to the H-criterion, there are differences in the level of cyberloafing between schoolchildren and students (H=9.36; p=0.002).

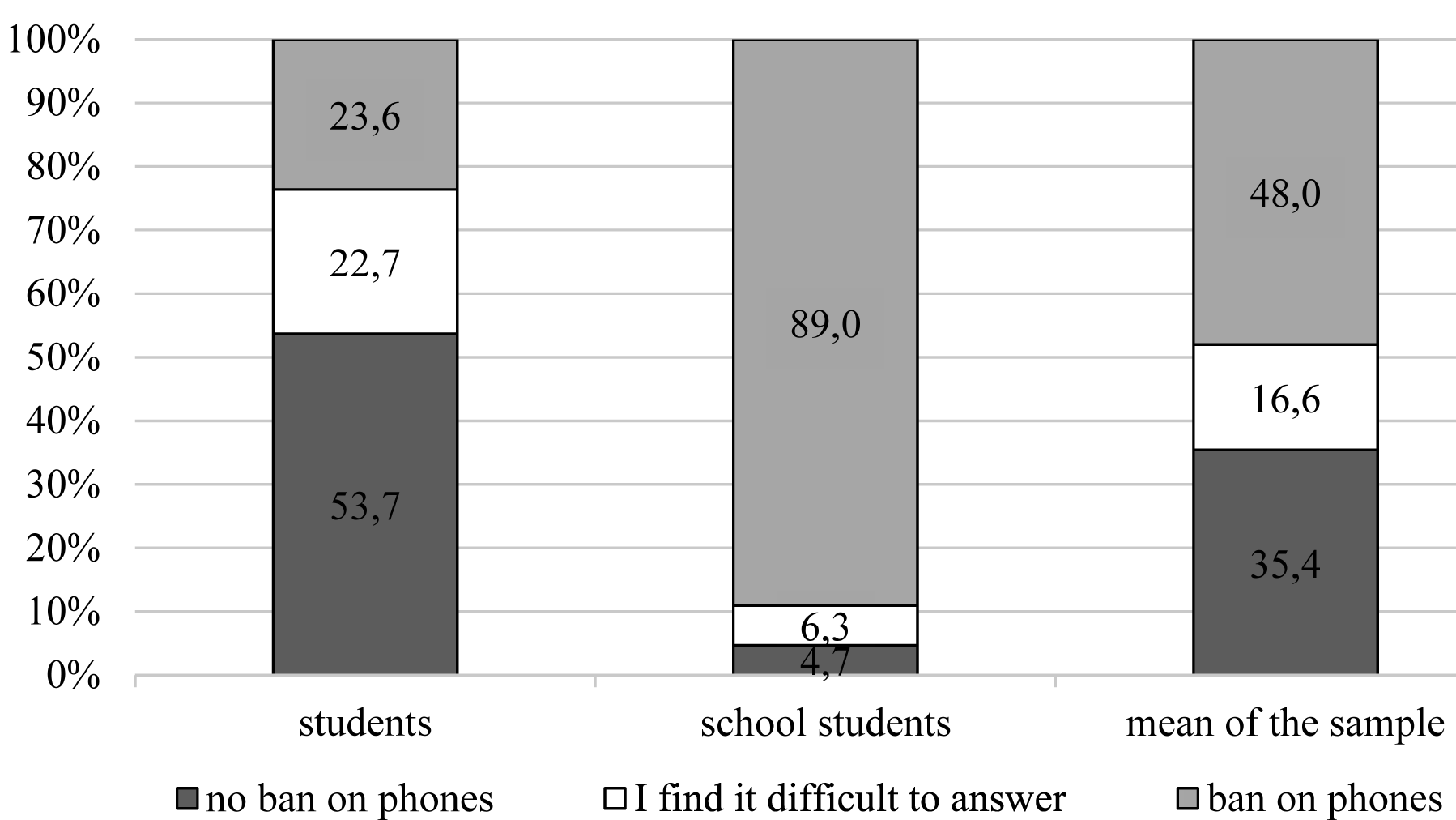

In this study, schoolchildren and students were asked whether there was a ban on the use of gadgets in classes in their educational institutions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Extending the ban on the use of telephones during school hours

89% of schoolchildren study under the conditions of banning the use of smartphones in lessons. Among students, the share of such students amounted to 23.6%. There is no such ban among 53.7% of students who participated in the study and 4.7% of schoolchildren who participated in the study.

It turned out that 48% of respondents study in educational organizations where there is a ban on phone use during classes, and 35.4% study without such a ban. 16.6% of respondents find it difficult to answer this question.

Pupils who know about the ban on using phones during study sessions are expectedly less likely to do so than pupils who do not know about such a ban or doubt its existence (N=10.16; p=0.006). However, as the results of the study showed, regardless of the presence/absence of prohibitive measures, both schoolchildren and students use phones for personal purposes during educational classes (Fig. 1).

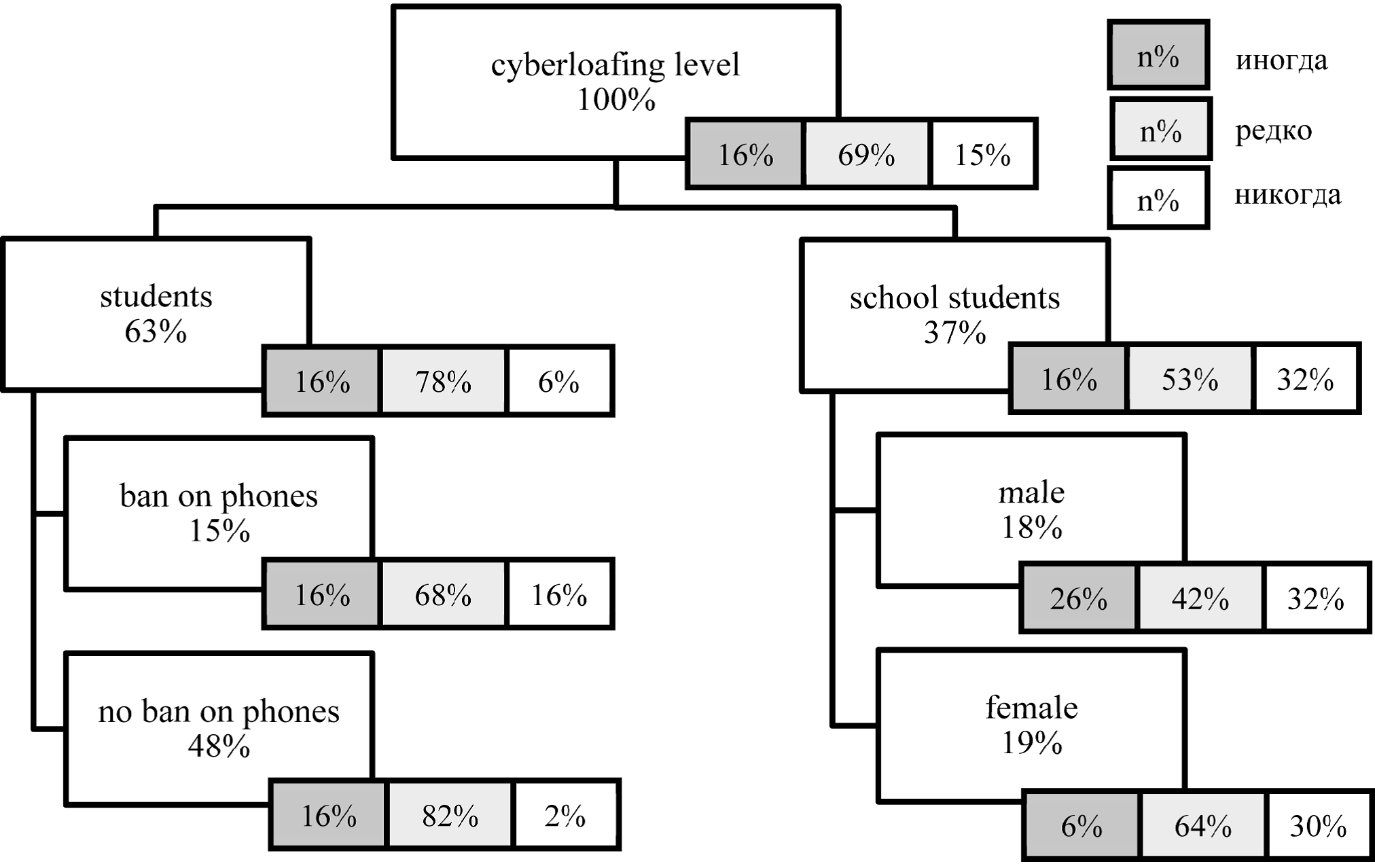

The findings indicate that gender, level of schooling, and prohibition of phone use in an educational institution affect the level of cyberloafing. Therefore, we used the CHAID analysis to examine the influence of these factors on the level of academic cyberloafing (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Level of cyberlapping according to gender, level of training and ban on phone use in an educational institution

The level of cyberloafing is primarily influenced by the level of education. The share of schoolchildren who never use a phone in class is higher among schoolchildren (32%) than among students (6%). Differences are reliable at p≤0.0001 (χ²=42.48). For schoolchildren, the second-order factor influencing the level of cyberloafing was gender: among boys, the share of those using the phone for personal use during classes was higher (26%) than among girls (6%). The differences are reliable at p≤0.01 (χ²=10.85). For students, the second-order factor influencing the level of cyberloafing turned out to be the ban on phone use in the educational institution: among students for whom there is no such ban, the share of students who do not use a smartphone in class for personal purposes was the smallest (compared to other segments of the sample)—2%. Among students who are aware of the ban on phone use in classes, the share of similar individuals amounted to 16% (χ²=42.48; p≤0.01).

Table 2 presents the results of the analysis of students' involvement in cyberbullying. Since preliminary data analysis using Fisher's exact criterion allowed us to refute the hypothesis about differences in the distribution of people involved in cyberbullying among students and pupils in the role of victim (Phi=0.092; p=0.223), aggressor (Phi=1.19; p=0.552), or witness (Phi=3.44; p=0.18), the table presents data for the entire sample. The vast majority (about 75%) of respondents were not involved in cyberbullying. About 20% encounter this phenomenon personally 1–2 times a month. About 2% of students experience cyberbullying more than 3 times a month in the role of victim and/or aggressor. Girls are less likely than boys to witness cyberbullying (U=12888; p=0.013). No differences in the structure of cyberbullying in schoolchildren and students were found during the study.

Table 2. Student involvement in cyberbullying

|

Engagement metrics |

Not once in a month |

1-2 times per month |

3 or more times per month |

|

|

|

Victim role |

Number of people |

268 |

68 |

8 |

|

|

% |

77,9 |

19,8 |

2,3 |

||

|

Aggressor role |

Number of people |

266 |

71 |

7 |

|

|

% |

77,3 |

20,6 |

2,0 |

||

|

Witness role |

Number of people |

256 |

86 |

2 |

|

|

% |

74,4 |

25,0 |

0,6 |

||

It should be noted that there were very few people in the study sample who were involved in cyberbullying in only one role. Thus, the number of victims who would not have witnessed cyberbullying and cyberbullied at any time in the last month was only 28 (8.8%) people. The number of “pure” aggressors was even lower, at 12 people (3.8%). All other study participants who had been involved in cyberbullying 1 or more times in the last month played different roles in these situations.

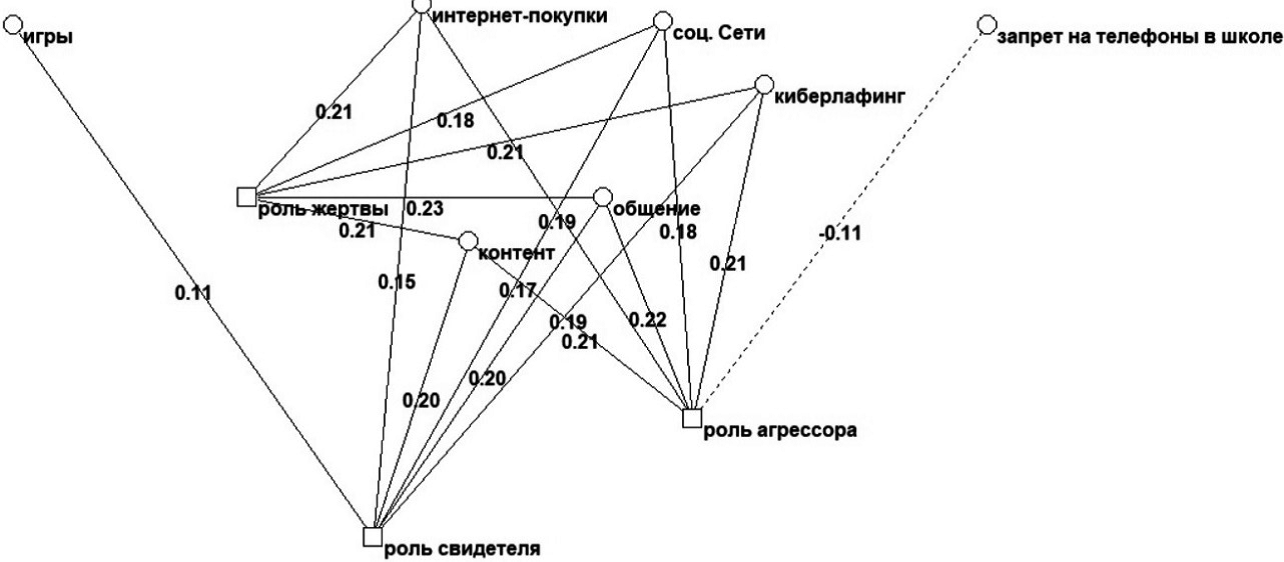

Correlation analysis of the data showed that the level of cyberloafing correlated with cyberbullying involvement in any role. Direct correlations were found between all forms of cyberbullying considered in the study and cyberbullying involvement in different roles (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. Linking cyberbullying engagement to cyberloafing

The exception was gaming cyberbullying, which was only associated with involvement in cyberbullying in the role of a witness (rs=0.11; p=0.05). Prohibition of phone use in an educational institution correlates with involvement in cyberbullying in the role of an aggressor (rs=-0.11; p=0.05). Moreover, this correlation is inverse in nature.

There are weak direct correlations between the level of cyberloafing and involvement in cyberbullying in the role of victim (rs=0.207; p=0.0002), in the role of aggressor (rs=0.206; p=0.0002), and in the role of witness (rs=0.187; p=0.001). It should be noted that all the correlations found were weak (0<rs<0.3).

Discussion

An important aspect of studying deviant behavior is analyzing its spread within society. The results of the current study indicate that in Russia, the prevalence of cyberloafing remains low (M=2), compared to M=3.8 among students in Israel. However, given the changes made to education law in December 2023, one might have assumed that such a phenomenon in schools would have been eliminated. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Despite existing bans, schoolchildren continue to use their phones during lessons. While these bans do influence the level of cyberloafing, they do not completely eradicate it. Specifically, if students are aware of a school's prohibition on phone use during class, they are likely to use their devices less frequently. The results confirm previously observed differences in cyberloafing between students of different genders and educational levels. A significant finding from this study is that the level of cyberloafing among students primarily depends on the presence of a ban on phone use in educational institutions, while within gender groups, it largely varies based on their gender.

The predominant forms of cyberloafing among students include internet content consumption (M=2.0), communication (M=1.9), and social networking (M=1.8). Gaming cyberloafing and online shopping are the least common activities, both at M=1.7.

The psychological interpretation of these findings emphasizes the importance of internet content and communication as the main sources for satisfying the respondents' needs. The comparatively high level of internet content consumption (M=2.0) during study sessions suggests that participants seek distraction through entertainment resources. This indicates that learners actively pursue and engage with various types of content—be it videos, audio, text, or memes—underscoring their desire to remain connected to current trends. Additionally, the significance of communication and social media highlights the importance of social connections in the lives of the study participants. Social networks serve as venues for forming identities, sharing opinions, and finding support during challenging moments. In contrast, the lower rates of gaming cyberloafing (M=1.7) and online shopping (M=1.7) imply that students may prioritize collective interactions over individual entertainment and consumer practices, thereby enhancing social bonds and developing sociocultural skills in the digital environment.

Education plays a significant role in shaping users' skills in the online arena and their perceptions, highlighting the correlation between educational levels and cyberloafing (p≤0.0001; χ²=42.48). It can be inferred that among young people, those with more advanced internet communication skills—likely distinguishing students from high schoolers—tend to engage in higher levels of cyberloafing. Conversely, students may face increased distractions from the internet during study sessions due to the greater freedom allowed in using personal devices.

The observed differences in the levels of cyberbullying among schoolchildren of various genders (p≤0.01; χ²amp=10.85) can be attributed to prevailing social and cultural stereotypes that influence online behavior. Generally, girls are more susceptible to social pressure and are more likely to adhere to rules and norms. In contrast, boys may be more inclined to breach school regulations and engage more extensively with internet technologies.

For students, a significant factor in determining the level of cyberloafing is the restriction on phone use in educational environments (p≤0.01; χ²amp=42.48). This phenomenon can be explained by the decreased oversight that universities have over personal device usage during classes. Consequently, when teachers or universities implement policies against gadget use in class, instances of cyberloafing tend to decline.

The investigation into the structure of cyberbullying revealed that approximately 22% of participants have experienced cyberbullying as victims. This finding aligns with data on Russian schoolchildren reported in 2018 and corroborates findings from students in other countries. This indicates that more than one in five individuals has encountered online bullying, humiliation, and threats. The results highlight the pervasive nature of cyberbullying and the urgent need for serious attention and preventive measures.

It is crucial to prioritize online safety and extend support to those affected by cyberbullying, as victims may experience severe psychological repercussions, including feelings of isolation, helplessness, anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem. These individuals may also withdraw from social situations, struggle with concentration, and find it challenging to form relationships. Furthermore, cyberbullying can undermine self-worth and lead to physical issues such as sleep disturbances, headaches, and digestive problems. Prolonged online harassment can result in serious consequences, including suicide attempts.

Given the serious psychological effects of cyberbullying, it is imperative to implement proactive measures to combat it. Key actions could include educating individuals about the consequences of cyberbullying, developing strategies to prevent it in schools and other organizations, and providing psychological support for victims.

Researchers have observed that students generally engage in cyberbullying to a lesser extent compared to other forms of bullying, such as social, physical, and verbal bullying. However, the evidence regarding gender-related differences varies across studies. Our research found that boys are more likely to witness cyberbullying than girls. Furthermore, in studies involving peers, the differences were linked to participation in cyberbullying as aggressors. These discrepancies could stem from variations in the samples studied; our research focused on high school and college students, whereas others examined only high school students.

Additionally, the results of previously conducted studies on cyberbullying do not permit an unambiguous assessment of gender differences. Some authors argue that participation in cyberbullying is more characteristic of boys, while others contend that it does not depend on gender. It is important to note that international studies pay insufficient attention to children's involvement in cyberbullying as witnesses, even though it is recognized that cyberbullying often occurs in group situations. Consequently, how young people react when they witness cyberbullying is crucial for addressing this issue. Inconsistencies across studies highlight the difficulty in understanding gender differences in cyberbullying, as factors such as age, culture, and social context can all influence these differences.

The differences we observed can be interpreted through the lens of gender socialization. Traditionally, boys are socialized to be more aggressive and dominant, which may explain their higher likelihood of witnessing cyberbullying. They are more likely to encounter aggressive online behavior because it aligns with their gender role. In contrast, girls are socialized to be more compassionate and caring, which may reduce their likelihood of witnessing cyberbullying. Girls do not typically seek out online situations involving aggression and tend to unconsciously avoid such scenarios.

Regarding social norms between boys and girls, it can be hypothesized that boys may experience social peer pressure to exhibit masculinity. This pressure might result in boys refraining from intervening, even when they witness cyberbullying. On the other hand, girls often strive to conform to norms of empathy and support, prompting them to take action by either preventing or reporting instances of cyberbullying.

The correlations between the individual components of the role structure of cyberbullying and the types of cyberbullying identified in the study are strikingly similar. The sole exception was the correlation between involvement in cyberbullying as a witness and in-game cyberloafing. This suggests a lack of connection between the structure of cyberbullying and specific types of cyberloafing. However, it is important to consider that the role structure of cyberbullying indicates a fluid transition from one role to another. For instance, a single individual may assume the roles of aggressor, victim, and witness in different situations, while their level of cyberloafing remains constant. This dynamic may have significantly influenced our findings. To properly distinguish between those who act strictly as cyberbullies, victims, or witnesses, the sample size must be considerably increased. In our study, only 28 individuals (8.8%) were victims who did not witness cyberbullying, and the number of 'pure' aggressors was even smaller, at 12 individuals (3.8%). Notably, there were no witnesses of cyberbullying who were neither aggressors nor victims in the sample. In the future, we plan to expand the sample size, although this does not guarantee an increase in respondents who fit into a single role within a cyberbullying scenario.

The relationship between involvement as a cyberbullying victim or witness and the use of gadgets during school hours for purchases may indicate an attempt to compensate for negative experiences through the consumption of products or services. Furthermore, the connection between involvement as a victim or witness and online communication during school hours can be understood in the context that these individuals may remain active online—communication remains a vital aspect of socialization for them—while opting for less harmful platforms like messengers or forums. These channels provide them with the opportunity to connect with friends and receive support without facing aggressive comments or actions.

Additionally, the link between being a victim or witness of cyberbullying and consuming internet content during class may reflect the desire of victims to distract themselves from negative thoughts and escape unpleasant realities and experiences. Similarly, the relationship between witnessing cyberbullying and levels of in-game cyberloafing may also serve as a form of escape from an uncomfortable reality. These interpretations are based on assumptions about individuals' psychological responses to the stress of cyberbullying situations. It is essential to recognize that each experience is unique, and the specific motivations for using gadgets may vary among different students.

The relationship between involvement in cyberbullying as an aggressor and the use of gadgets for online shopping, as well as the consumption of Internet content during class, can be understood through the fact that cyberbullies are typically active users of the Web. Social media serves as a significant platform for their aggressive behaviors, prompting them to socialize online even during lessons. This explains the link between involvement in cyberbullying and the use of gadgets in class for communication, particularly through social networks.

Overall, it can be said that all participants in cyberbullying are Internet users. They often use the Internet during class for personal (non-educational) purposes. This is quite expected, especially when considering cyberbullying as a group phenomenon. However, it can be inferred that cyberloafing may serve different functions for various participants in cyberbullying.

The study found a weak correlation between academic cyberloafing and cyberbullying. We have yet to identify other studies that explore the correlation between these two phenomena, so it is currently impossible to compare our findings with existing literature. Nevertheless, our results align with existing research that suggests uncontrolled media consumption during adolescence leads to increased aggression. Additionally, our findings partially support the model proposed by F. Jabin and A. Tandon, which posits that boredom in the classroom can lead to behavioral responses such as cyberloafing, consequently heightening the risk of increased involvement in cyberbullying. It is important to note that correlation analysis alone does not allow us to draw conclusions about causal relationships between these phenomena, indicating that further investigation is needed to clarify cause-and-effect dynamics.

The weak correlation observed between cyberloafing and cyberbullying may be influenced by a third variable impacting both. For instance, internet addiction could play a significant role. The use of gadgets during class may reflect internet addiction, where an individual feels incomplete without their smartphone. Concurrently, the drive to remain constantly online can elevate the risk of encountering cyberbullying. It is plausible that a common factor influencing both cyberbullying and cyberloafing is the amount of time spent online. The more time spent on the Web, the higher the likelihood of engaging in destructive cyber behavior. This study does not provide definitive answers regarding the validity of these hypotheses, nor can it confirm if both are incorrect. However, testing these hypotheses could represent a logical progression for future research.

Conclusion

The results of the study allow us to draw the following conclusions:

- The study identified predominant forms of cyberloafing among students, including consuming internet content (M=2.0), social networking (M=1.8), and online socializing (M=1.9). Less frequent behaviors included gaming and online shopping (both M=1.7). The level of cyberloafing was primarily influenced by education level (p≤0.0001; χ²amp=42.48). Among high school students, gender was a secondary factor (p≤0.01; χ²amp=10.85), whereas, for university students, institutional phone bans played a significant role (p≤0.01; χ²amp=42.48). The hypothesis that cyberloafing levels depend on gender, education level, and phone restrictions was confirmed.

- The overall involvement of study participants in cyberbullying was low (approximately 22%). Gender differences were observed only in the role of cyberbullying witnesses (U=12888; p=0.013). While the hypothesis that cyberbullying involvement is gender-dependent was partially confirmed, the hypothesis that it varies by education level was not supported.

- The study revealed a correlation between cyberloafing and cyberbullying. Specifically, being a cyberbullying victim was associated with behaviors such as online shopping (r=0.21; p=0.05), social networking (r=0.18; p=0.05), online communication (r=0.19; p=0.05), and consuming internet content (r=0.21; p=0.05). Similarly, cyberbullying perpetrators exhibited correlations with social networking (r=0.18; p=0.05), online communication (r=0.22; p=0.05), online shopping (r=0.21; p=0.05), and internet content consumption (r=0.21; p=0.05). Witnesses of cyberbullying also showed links to social networking (r=0.19; p=0.05), online communication (r=0.2; p=0.05), online shopping (r=0.15; p=0.05), and internet content consumption (r=0.2; p=0.05). These findings confirmed the hypothesis that cyberbullying involvement is related to cyberloafing levels.

The intended purpose of the study was achieved: the link between cyberloafing and cyberbullying was uncovered. The present work supplements the existing data on new forms of deviant behavior in connection with the use of virtual space. In particular, the prevalence of cyberloafing and cyberbullying among Russian pupils and students.

Based on the theory of cyberbullying as a group action phenomenon and the perceptions reflected in the SOPA model of social media use, it was possible to explain the observed relationships between cyberloafing and cyberbullying. These theoretical foundations suggest that in the context of cyberloafing and cyberbullying, not only the feeling of lonelinessor the need for communication, but also boredom or the search for entertainment may be the original stimulus. This could explain the relationship between the two.

The present study excludes the possibility of finding causal relationships between the phenomena due to the use of cross-sectional data. This can only be inferred from the theoretical concepts of cyberloafing and cyberbullying, which have their limitations, including in the research methodology. Additional limitations arise from the use of an exclusively quantitative data collection and analysis strategy, which is exacerbated by the relatively small sample size. In order to minimize negative effects as much as possible, we paid particular attention to selecting the right data processing methods.

The use of self-report, especially in relation to deviant behavior, may be biased by the social desirability factor, which reduces the validity of the current study.

The set of factors examined in this study is also limited: Education, gender and smartphone ban. At the same time, one should be aware that there are other potentially significant factors that influence the variables studied, such as socioeconomic status, psychological well-being, and parental and teacher control.

Further research on this problem should be devoted to exploring other age groups and spatial (urban/rural) contexts, as well as other indicators of cyberloafing and cyberbullying patterns. In this context, it will be useful to increase the sample and geographical scope of the study. It will be useful to use qualitative methods to collect data on the phenomena under study in order to gain a deeper insight and understanding of the nature of the phenomena under study. An example of expanding the number of variables for further research could be the inclusion of teachers' behavior as participants in the educational system and as a factor influencing children's behavior in the classroom.