Introduction

According to social identity theory, a person is aware of his place in the world by referring to those social groups that have emotional significance for him [Tajfel]. However, the self-image of the individual is formed not only by the very fact of his identification with a particular social group, but also by the characteristics of this group and the peculiarities of the individual’s perception thereof.

Social psychologists have defined the essence of a perceived group, that is, the perception of the group as an object or as a coherent whole, as one of the important features of group perception [Campbell; Sani, a]. S. Reicher and N. Hopkins [Reicher, a] assumed that such groups are perceived by people as continuous, that is, as entities that move through time. Being a member of such a group, a person perceives himself as a small part of a continuously existing “organism”, which is not only spatially larger than him, but also existed before and will exist after him. Based on these studies, F. Sani and colleagues [Sani, 2007] formulated the theory of perceived collective continuity, which implies that the culture and history of a social group can be transmitted and preserved from generation to generation. S. Reicher and N. Hopkins highlighted how much effort and time the members of the group spend exalting and expressing respect for their past group experiences, and protecting their own interpretation of historical events [Reicher, a]. This sense of collective continuity provides elevation, and also allows an individual to protect the group, its experience, and the events associated with it. For example, although people are aware that they will die, a sense of collective continuity offers existential security [16–18], since this feeling implies that the part of a person that is determined by his or her membership in a group has temporal stability and is transformed into an “eternal we” [Reicher; Jetten, 2011]. Based on this connection with the past, group members are able to gain a deeper understanding of themselves, as well as of intra- and inter-group processes.

F. Sani and colleagues [Sani, 2007] believe that the sense of perceived collective continuity is based on two grounds: cultural and historical. The first view is related to the belief that core values, traditions, and beliefs are transferred within a group from generation to generation. Belief in cultural continuity implies that, in the minds of people, a group has stable and permanent cultural features that characterize it at any time during its existence. The second view, historical, refers to the perceived relatedness of different time periods in the group's history to each other. The authors of the theory describe this as a “continuous flow” — when various eras, times, and events in the history of the group are perceived as sequentially and logically connected to each other, forming a continuous story or narrative. This sense of collective historical continuity includes not only the past, but also the belief that the group will exist in the future [Wohl].

The authors consider historical and cultural perceived collective continuity to be interrelated, but emphasize the conceptual difference between the perception of the continuity of traditions and the continuity of historical periods. This means that the perception of the group may be dominated by one of these aspects. Moreover, it may also be associated with different characteristics of the group and the consequences for its members. For example, for a group that has radically changed its political regime, high cultural continuity may be undesirable because it would mean the transmission of old beliefs and traditions. However, high historical continuity may, on the contrary, help to emphasize the weight of the historical change that has taken place and explain the transformations [Sani, 2007].

F. Sani and colleagues [Sani, 2007] showed that the perception of a group as an entity existing in time is associated with social identity, the perception of group entitativity, and the collective self-esteem of the group. This construct is actively considered in studies of various socio-psychological phenomena such as social well-being [Sani, 2008], essentialist beliefs [Siromahov], fear of death [Sani], and resistance to a group merger [Jetten, 2011]. Also, perceived collective continuity is directly reflected in more global processes, touching on the topics of intergroup relations [Warner], social identity [Smeekes, a], and group dynamics [Smeekes, 2015].

Methodology for Assessing Perceived Collective Continuity

The only methodology for assessing perceived collective continuity was presented in 2007 by F. Sani and colleagues. The scale includes 12 statements, 6 for each aspect of continuity. The scale of historical perceived collective continuity contains statements about the connection between time periods in the history of the group (for example, “Italian history is a sequence of interconnected events”). The scale of cultural continuity includes statements about the transmission and preservation of traditions or beliefs across generations (for example, “Italian people have passed on their traditions across the generations”). This scale showed high internal consistency (a = 0.8), as were scales of historical and cultural representation (a = 0.86 and a = 0.71, respectively). Reviewing the structure of the construct confirmed its two-factor nature, highlighting the historical and cultural representations.

The scale is actively used by authors all over the world. Translations have been made into Dutch, Greek and Turkish [Smeekes, a; Smeekes, 2017]. All translations show good agreement between the scales, but empirical evidence does not always support a two-factor structure. In particular, in Turkey, such a structure has not been confirmed, which may indicate the cultural specificity of the perception of judgments (for example, in some countries, culture and history can be considered to be an inseparable single whole).

The growing relevance of group studies in terms of the perception of their temporal characteristics leads to a deeper study of this construct and its connection with psychological phenomena. Thus, for example, perceived collective continuity can explain increased outgroup hostility [Warner], resistance to a group merger [Jetten, 2011], and ingroup defense motives [Smeekes]. The methodology of collective continuity can be a useful tool for studying the characteristics of the perception of social groups, the characteristics of its members, and intergroup relations in Russia.In contemporary Russia, there are many groups (civil, ethnic, national), for which the construct of collective continuity can predict and explain not only the perception of their own group, but also important intergroup processes. In addition, collective continuity can explain the perception of historical processes in Russia. The Russian Federation is a young state, the creation of which could “interrupt” the collective continuity of the group. Thus, according to a Levada survey, Russians rate the Soviet government better than the current one, and regret the collapse of the Soviet Union [Chelovek sovetskii: kak].

The purpose of this article is to adapt the scale for assessing the perceived collective continuity of Russia as perceived ethnic group of Russians, since Russians are the largest ethnic group in Russia. It was important not to choose an ethnic group based on citizenship (Russian citizens), but an ethnic group (ethnic Russians), since it is the ethnic group that is perceived as genetically predetermined, which is why the entitativity of such groups is highly valued [Agadullina, 2017].

Participants

The study involved 637 residents of Russia who identify themselves as ethnic Russians, aged 18 to 79 (M = 36.71, SD = 10.59, 50.9% men). Most of the respondents have one or more higher educational degree (57.1%), others had yet to complete higher education (9.4%), the rest have completed general secondary (10.5%) or secondary specialized education (22.4%).

Methods

Perceived collective continuity was measured using the methodology of F. Sani and colleagues, translated into Russian by two translators independently from each other. Further, as a result of comparing the two options and conducted cognitive interviews with respondents, the final version of the scale was compiled, consisting of 12 judgments (see Appendix 1), of which 6 relate to cultural representation (for example, “Throughout history, Russians have retained their mentality” ; M = 5.12, SD = 1.09, α = 0.87), and the other 6 – to the historical one (for example, “There is a causal relationship between various events in the history of Russia”; M = 5.42, SD = 0.92, α = 0.83). Each judgment was to be scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

F. Sani and colleagues [Sani, 2007] relied on the connection between continuity and constructs related to the phenomena of group identification, since, in group identification, people can tend to fulfill their psychological need for incessancy and continuity (or a sense of symbolic immortality). Therefore, an ingroup that is perceived as culturally and historically contiguous must reinforce its own sense of continuity, which in turn must reinforce group identification, the positive evaluation of the group, and emotional connection with the group. The following methods were used to test the convergent validity of the scale:

Perceived group entitativity was assessed using three judgments: “Russians can be seen as a cohesive group / Russians can be seen as an organized group / Russians can be considered as a single whole” [Agadullina, 2017]. Each judgment had to be evaluated using a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (α = 0.89).

Group identification was measured using a two-factor scale [Leach] adapted to Russian [Agadullina, 2013]. The scale includes 14 judgments (for example, “Being a Russian makes me happy”), combined into 5 scales. Each statement must be scored on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (α = 0.94).

Feeling thermometer was assessed through respondents' assessment of how unfavorable/sympathetic and negative/warm feelings they have towards Russians, indicating a number from -5 (unfavorable/negative feelings) to +5 (sympathy/warm feelings) (α = 0.96) [Warner].

To assess the discriminant validity of the scale, methods from the Big Five were used, aimed at assessing the scales of extraversion (a = 0.79) and neuroticism (α = 0.86) [Shchebetenko, 2015]. Each scale includes 9 statements that must be rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). These traits were chosen to test the discriminant validity, as these are stable personality constructs that are not associated with group phenomena.

Results

Both components of the scale showed high internal consistency (α > 0.8) (Table 3). Table 1 shows descriptive statistics of the statements. As can be seen from the data, all statements have a left skewed distribution, that is, the respondents are more likely to agree with them. Most of the statements have positive kurtosis, indicating a distribution where not enough respondents have low or high enough scores to be considered a normal distribution. This means that most of the statements display a low variance.

Table 1

Descriptive statistics on methodology items and item-total correlations

|

№ |

Formulation of items |

M (SD) |

Med |

Skew |

Kurtosis |

r (H/C) |

r |

|

1 (C) |

Russians transfer their traditions from generation to generation. |

5.07 (1.31) |

5 |

-0.888 |

0.57 |

0.52 |

0.47 |

|

2 (H) |

The history of Russia is a sequence of interconnected events. |

5.58 (1.22) |

6 |

-1.270 |

1.856 |

0.56 |

0.56 |

|

3 (C) |

Russian values and beliefs have stood the test of time. |

5.11 (1.52) |

5 |

-0.792 |

-0.107 |

0.70 |

0.65 |

|

4 (H) |

The main periods in the history of Russia are connected with each other. |

5.45 (1.2) |

6 |

-1.234 |

1.823 |

0.64 |

0.58 |

|

5 (C) |

Throughout history, Russians have retained their mentality. |

5.28 (1.32) |

6 |

-1 |

0.668 |

0.64 |

0.58 |

|

6 (H) |

There is no connection between past, present and future events in the history of Russia. |

5.61 (1,3) |

6 |

-1.26 |

1.094 |

0.61 |

0.44 |

|

7 (C) |

Russians will always be distinguished by their traditions and beliefs. |

5.34 (1.33) |

6 |

-0.98 |

0.747 |

0.68 |

0.60 |

|

8 (H) |

There is a causal relationship between various events in the history of Russia. |

5.59 (1) |

6 |

-1.292 |

2.538 |

0.61 |

0.49 |

|

9 (C) |

Russia has preserved traditions and customs throughout its history. |

4.96 (1.44) |

5 |

-0.85 |

0.031 |

0.78 |

0.68 |

|

10 (H) |

The main events in the history of Russia form a continuous chain. |

5.14 (1.32) |

5 |

-0.993 |

0.575 |

0.66 |

0.68 |

|

11 (C) |

Russians have always adhered and adhere to their own values. |

4.97 (1.4) |

5 |

-0.806 |

0.076 |

0.74 |

0.64 |

|

12 (H) |

There is no continuity between different periods in the history of Russia. |

5.14 (1.39) |

6 |

-0.83 |

-0.097 |

0.52 |

0.38 |

Notes. M — mean; SD — standard deviation; Med — median; r (H/C) — correlation with the sum of the remaining items of historical or cultural representation; r — correlation with the sum of the remaining items of the entire scale; H — historical representation; C — cultural representation.

To assess structural validity of the scale, confirmatory factor analysis was performed using the lavaan package for R 4.0.4 [Rosseel]. Values of RMSEA < 0.06 and SRMR ≤ 0.08; TLI ≥ 0.95 [Schreiber]; CFI ≥ 0.95 and X2/df < 3 [Hu] were chosen as indicators of good model quality [Gatignon].

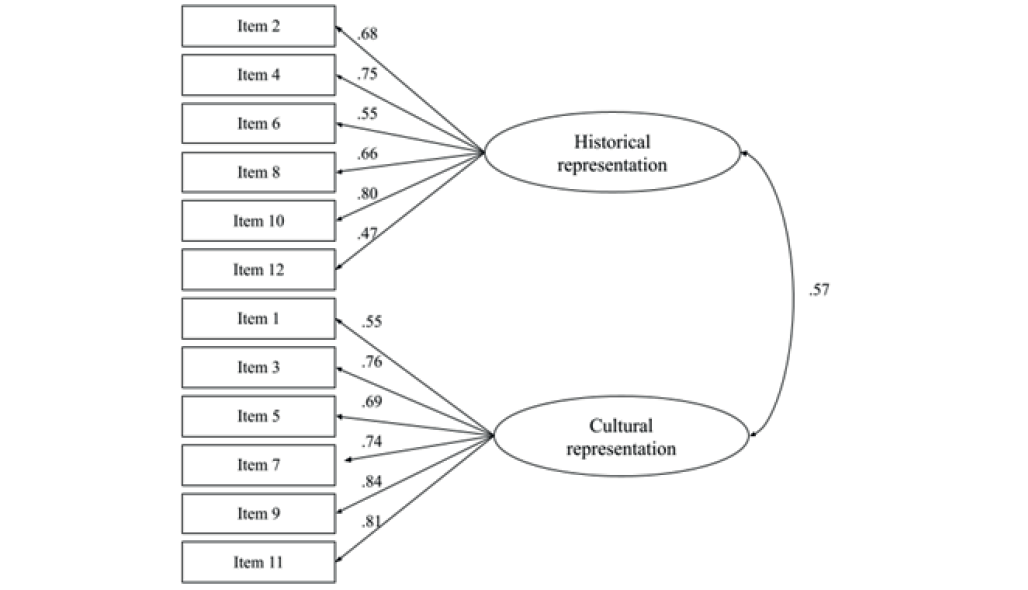

The initial model showed poor fit with the data: χ2 (53) = 226.04, RMSEA = 0.071 [90% CI: [0.064; 0.08], CFI = 0.918, TLI = 0.897, SRMR = 0.060. Modification indices showed that there is a high error covariance between the two reversed (negatively-worded) items (6 and 12), which can be explained by the fact that the remaining items in the scale are positively-worded. The model adjusted for the revealed covariance (Fig.) demonstrates a good fit to the empirical data: χ2 (52) = 135.89, RMSEA = 0.05 [90% CI: [0.041; 0.059], CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.949, SRMR = 0.046.

Fig. Perceived Collective Continuity Measurement Model with Factor Loadings

To test the invariance of the scale across different sociodemographic groups, a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis (MCFA) was conducted. Three levels of scale invariance were assessed: structural (assesses whether items in different groups belong to the same factors), metric (assesses whether factor loadings of items in different groups are comparable) and scalar (assesses whether the “complexity” of items is identical in different groups). With the help of multigroup factor analysis, the scores of the scales among men and women were compared. According to the standards, the difference in CFI between the invariance models should not exceed 0.01 [Fischer], therefore, according to the results presented in Table 2, it can be argued that the scale demonstrates complete invariance, that is, the scale works the same across gender groups.

Table 2

Results of multigroup factor analysis

|

Groups |

Model |

χ2 |

df |

RMSEA [90% CI] |

SRMR |

CFI |

TLI |

AIC |

BIC |

δχ2 |

δdf |

δCFI |

|

Gender groups (men, women) |

Structural invariance |

192.78* |

104 |

0.052 [0.042- 0.061] |

0.048 |

0.959 |

0.948 |

22973 |

22635 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Metric invariance |

196.65* |

114 |

0.0478 [0.038- 0.057] |

0.056 |

0.966 |

0.956 |

22914 |

22620 |

3.88 |

10 |

0.003 |

|

|

Scalar invariance |

210.49* |

124 |

0.047 [0.037- 0.056] |

0.053 |

0.96 |

0.957 |

22862 |

22612 |

13.83 |

10 |

-0.002 |

Notes. х2 — chi-square test; df — number of degrees of freedom; RMSEA — mean square error of estimation; SRMR — standardized root mean square residual; CFI — comparative fit index; TLI — incremental fit index; AIC — Akaike information criterion; BIC — Bayes information criterion; p < 0.001‘*’

To check the validity of the construct, a correlation analysis was conducted, the results are presented in Table 3. Convergent validity was confirmed by the significant correlations obtained with group entitativity (r (635) = 0.57, p < 0.001), group identification (r (635) = 0.62, p < 0.001) and feeling thermometer (r (635) = 0.49, p < 0.001). A weak positive correlation of collective contuinity with extraversion (r (635) = 0.17, p < 0.001) and a weak negative correlation with neuroticism (r (635) = -0.15, p < 0.001) confirmed the discriminant validity of the adapted scale.

Table 3

Descriptive statistics and correlations with other constructs

|

Scale |

M (SD) |

α |

1. |

1.1 |

1.2 |

2. |

3. |

4. |

5. |

|

1.Perceived collective continuity |

5.27 (0.85) |

0.87 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.1. Historical representation |

5.42 (0.92) |

0.83 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1.2. Cultural representation |

5.12 (1.09) |

0.87 |

|

0.45* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

2.Perceived group entitativity |

4.21 (1.41) |

0.89 |

0.57* |

0.33* |

0.63* |

|

|

|

|

|

3.Group identification |

5.09 (1.11) |

0.94 |

0.62* |

0.37* |

0.65* |

0.61* |

|

|

|

|

4.Feeling thermometer |

9.20 (1.89) |

0.96 |

0.49* |

0.32* |

0.51* |

0.46* |

0.65* |

|

|

|

5.Extraversion |

2.93 (0.73) |

0.79 |

0.17* |

0.06 |

0.21* |

0.25* |

0.28* |

0.24* |

|

|

6.Neurotism |

3.03 (0.80) |

0.86 |

-0.15* |

-0.06 |

-0.19* |

-0.24* |

-0.24* |

-0.21* |

-0.42* |

Notes. M — mean; SD — standard deviation; α — Cronbach's alpha; p < 0.05 ‘*’

Discussion

The article presents the adaptation of the perceived collective continuity scale into the Russian language. Empirical data have shown that the Russified perceived collective continuity scale fits both the original factor structure and psychometric standards of validity and reliability. Therefore, collective continuity can be studied in the Russian context, using both the whole scale and subscales for various aspects of continuity.

In particular, based on the assumption that a connection between certain aspects of the perceived collective continuity and different characteristics of the group and the consequences for its members exists, the historical context aspect of the theory can be used to explain the differences between ethnic and national groups living on the territory of Russia.

Notably, over the past century, three different states have succeeded one another in what is now the Russian Federation in terms of borders and denomination. Therefore, since members of social groups tend to spend a lot of effort in protecting their own interpretation of historical events and respecting their group experience [Reicher, a], the construct of perceived collective continuity may allow us to explain relations with groups living in countries that wereunited with Russia as one state within certain historical periods. Moreover, such states had a different territorial composition and hierarchy of values. High perceived collective continuity can predict outgroup attitudes. The higher the perceived collective continuity, the more extreme the attitudes become both for neutrally or positively assessed outgroups (attitudes towards them become even more positive), and for negatively assessed outgroups (attitudes towards them become even more negative) [Warner]. This influence can help explain intergroup processes not only within Russia, but also in relation to groups outside of it.

In addition, perceived collective continuity is being actively studied in light of rising existential security and reduced fear of death. This may also be relevant for the Russian context, where an appeal to history and culture can serve a protective function.