Introduction

In modern society, where the social role of the family is changing and the importance of marriage tends to be underestimated or denied, the problem of family resilience becomes particularly relevant. Family resilience, the experience of close relationships and emotional experience acquired in parental families become the most important aspects of the social situation of personal development in the family, including the development of resilience, which is one of an individual’s key assets. Based on the analysis of a significant number of approaches and concepts, it is shown that there is no single understanding of vitality, but generalizing various authors’ views, it is possible to state that it is understood as «creative realization of one’s personal potential, resistance not to the requirements of a particular life situation, but to the opportunities it provides for the implementation of one’s own goals, senses, purposes of a person, it is courage to live and to create life» [M. A. Psikhologiya, 2015, p. 179]. Resilience is understood as a dynamic characteristic of the family, ensuring its sustainability to respond flexibly to modern challenges, change, adapt and evolve [Gusarova, 2021; Makhnach, 2018].

Data on resilience is more relevant to studying family resilience because the vitality of the people who start the family serves to underpin family resilience.

The cross-cultural aspect of family resilience is also interesting. Comparative studies of family resilience are particularly important for nations with similar historical destinies and close links in politics, economy and culture, as is the case with Russia and Belarus. Researchers stress the importance of cross-cultural studies of this problem [Ani, 2022]; the growing interest in them is evidenced by numerous adaptations of M. Sixby’s Family Resilience Assessment Scale (FRAS) in different countries and cultures [Chow, 2022; Isaacs, 2018; Laporte, 2022; Nadrowska, 2017; Zhou, 2020], which find cross-cultural differences in the structure of family resilience, but do not explain their nature.

Despite the interest in this issue in the field of psychology, comparative studies on Russian and Belarusian families’ resilience have not been conducted. Conflicting data on personal coping resources, including vitality, have been obtained from comparative studies of Russian and Belarusian students’ individual vitality [Leonenko, 2020], different generations of Belarusians and Russians [Odintsova, 2019]. It is shown that the level of accepting risk as one of the characteristics of vitality is higher among Belarusian students than among Russian students [Leonenko, 2020]. At the same time, due to differences in cultural and historical conditions of different generations’ life, the level of personal resources of Russian youth is shown to be higher than that of Belarusian one [Odintsova, 2019].

Analysis of the literature shows that most authors link the characteristics of family resilience and vitality to the values of people's culture in one way or another. There are several approaches to the genesis of national culture values. For example, V.G. Krysko [Krys'ko, 2002] attaches great importance to the historical aspects of ethnogenesis. Based on his works, N.O. Leonenko and co-authors define ethnic identity as a psychological mechanism of forming national culture values. According to N.O. Leonenko, Eastern European students are less resistant if they have a low level of ethnic identity [Leonenko, 2014]. Obviously, ethnic identity has not only quantitative, but also substantive characteristics, which are culturally and historically conditioned.

Hofstede attempted to use parameters such as power distance, individualism, uncertainty avoidance, masculinity and long-term orientation to reflect the meaningful characteristics of culture. His model is used to describe personality types under certain cultural and historical conditions [Naumenko, 2021]. However, this model is poor at predicting individual behavior [Lebedeva, 2023]. J. Wertch's narrative approach [Wertch, 2021] considers the content of ethnic identity and cultural characteristics in the context of people's historical memory. This is understood as a narrative in which historical events have different meanings for different peoples and, within a nation, for different social groups' representatives. One of the most important themes in the Russian historical narrative, as rightly identified by J. Wertch, consists in fighting the foreign invaders who wanted to enslave the country and in completing the victory. Researchers emphasize the complementarity of the narrative approach and cultural-historical theory [Sapogova, 2011].

The following statement may serve to illustrate the historical narrative of the Belarusian ethnos: «Resignation to the inevitable and readiness for full revival are proofs of Belarusians’ spiritual strength. Another argument of this spiritual strength is the Belarusian people's unprecedented resistance movement during the Great Patriotic War» [Leonenko, 2020, p. 326]. At the same time, we cannot ignore the tragic undertone of this narrative. A striking literary example are the works by the outstanding Belarusian writer Vasil Bykov, where the choice between moral loyalty and treason becomes the choice between death and a traitor's despised life. The implicit necessity of the choice between acceptance-humility or complete rebirth at the cost of suffering should also be noted in the content of this narrative.

We can assume that the family history narrative, which is an order in the consciousness of family members of significant events, including those representing difficult life situations, mediates the influence of historical narrative on family resilience. Naturally, the family narrative is formed under the significant influence of the folk memory narrative. Therefore, when studying family resilience, it is important to study family history events, which are closely connected with the country's history and mediate the influence of historical narrative on family personality development. Thus, in the first years after the collapse of the USSR, which were marked by a large-scale economic crisis, the historical narrative of the nation, thanks to the representatives of the older generation, strengthened the family's resilience, because the elders passed this narrative on to the younger generations in their families («We survived the war and will make it through this!»). However, the mechanisms by which individual vitality emerges in the context of historical narrative and familial resilience remain unclear. We can assume that these factors are, firstly, familial resilience, emotional communication at home and experience of close relations, and, secondly, specific social circumstances. This may account for the conflicting data obtained in the research by N.V. Murashchenkova and colleagues, which found a high level of civic identity among Belarusian students, but also a high level of resentment, disadvantage and emigratory tendencies [Murashchenkova, 2022; Murashchenkova, 2022a]. The nature of these contradictions and ideas about the influence of cultural and historical context on the development of vitality as a personal characteristic could be clarified by a cross-cultural empirical study aimed at identifying profiles of family resilience and individual vitality.

The study aims to analyze family resilience profiles, including family resilience, family emotional communication, experience of close relationship and individual vitality of representatives of Russian and Belarusian families.

Study objectives.

- To compare family resilience, emotional communication, and experience of close relationships among Russian and Belarusian families.

- To identify family resilience profiles and to analyze their correlation with demographics.

- To compare Russian and Belarusian family resilience.

Study hypothesis: Resilience profiles of Russian and Belarusian families are more similar than individual vitality characteristics of Russian and Belarusian representatives.

Methods

Study programme. The study was approved by MSUPE Ethical Committee (protocol no. 12 of 15.03.2022). The following methods were used therein.

- Russian version of the Family Resilience Assessment Scale by E.S. Gusarova et al. (41 points, subscales: «Family Communication», «Positive Forecasting and Problem Solving», «Acceptance and Flexibility», «Social Resources», «Spirituality») – to assess the resilience of the family to which a person considers himself/herself) [Gusarova, 2021].

- The questionnaire «Family Emotional Communications» (FEC) by A.B. Kholmogorova and S.V. Volikova (30 points, scales: «Parental criticism», «Inducing anxiety in the family», «Eliminating emotions in the family», «Fixation of negative experiences», «Striving for external well-being (hostility and facade)», «Overinvolvement» and «Family perfectionism») – to study emotional communications in the parental family [Kholmogorova, 2016].

- The questionnaire «Experience of Close Relationships» by Fraley R.C. et al., adapted by K.A. Chistopolskaya (14 points, scales: «Anxiety» and «Avoidance») - to study one's own experience of close relationships [Chistopolskaya, 2018].

- K. Adams' projective technique «Space of Trees and Light» [Odintsova, 2022]. The participant is shown four illustrations and is asked to choose the one that most closely reflects the period of his or her childhood. The first illustration («Living space») shows a child sitting next to a mighty tree, its roots reaching deep into the ground and its large crown serving as a defense. This space symbolizes the strong foundation of culture, tradition, and protection. The second picture, «Shimmering space», depicts a dark, dense forest, a path along which a child is walking, supported by an adult, and light shining through the trees. This space symbolizes the quest to understand their culture and traditions with the support of an adult. The third illustration, «Opaque space», depicts dusk, the sun is setting over the horizon, there are almost no trees, but the child's dark silhouette is clearly visible. The picture symbolizes loneliness, anxiety, worry and fear, but some cultural traditions are still present. The fourth picture is «Invisible space» with trees in the mist, there is no child in the picture. The picture symbolizes doubt, rejecting others, distancing from tradition and culture, «losing one's roots».

- A short version of the vitality test by E.N. Osin and E.I. Rasskazova (24 points) [Osin, 2013].

The first three questionnaires were used to investigate family resilience, family emotional communications in parental families and the experience of close relationships. K. Adams' projective technique was used to clarify these data. Method 5 was used to assess individual vitality.

When analyzing difficult life situations, the author's scheme developed over the classification proposed by E.V. Bityutskaya and A.A. Korneev was applied [Bityutskaya, 2021].

The study involved 803 participants, 399 from Russia (320 women and 79 men, mean age 31.6 + 12.4) and 404 from Belarus (345 women and 59 men, mean age 23.0 + 7.8).

Results

Comparison of average indicators of Russian and Belarusian families according to family resilience methods, questionnaires «Family emotional communications» and «Experience of close relationships» showed no significant differences on most scales, except those listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Differences in the characteristics of family resilience and emotional communication in Russian and Belarusian families

|

Parameters |

Russian families |

Belarusian families |

Mann-Whitney U test |

Significance of differences р |

|

||

|

Average |

Standard deviation |

Average |

Standard deviation |

|

|||

|

Spirituality |

24.74 |

6.16 |

23.70 |

6.03830 |

71086.5 |

0.004 |

|

|

Elimination of emotions |

8.57 |

3.96 |

7.89 |

3.67 |

72218.0 |

0.011 |

|

|

External well-being |

5.49 |

2.17 |

5.10 |

2.05 |

71262.0 |

0.004 |

|

Russian families more often turn to spirituality as a resource of family resilience and at the same time the rating of the emotions’ elimination and the demonstration of external well-being in parental families higher.

There are also significant differences between the representatives of the two countries, according to the data of K. Adams' technique «Space of Trees and Light» (Table 2).

Table 2. Choice of pictures of the projective technique «Space of Trees and Light» by representatives of Russian and Belarusian families

|

Country |

Picture |

Total |

χ², significance of differences |

|

|||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

|

||

|

Russia |

168 |

74 |

106 |

51 |

399 |

χ² = 11.383 р = 0.01 |

|

|

Belarus |

214 |

53 |

100 |

37 |

404 |

||

The data on K. Adams' projective technique «Space of Trees and Light» illustrate the differences in the characteristics of family resilience and family emotional communication in representatives of Russian and Belarusian families. The Russians chose the «Living Space», symbolizing a strong foundation and protection, significantly less often and the «Shimmering Space», symbolizing the desire to understand their cultural environment with the support of an adult, more often. On the contrary, representatives of Belarusian families were much less likely to choose the «Invisible Space», which illustrates «loss of roots», distance from traditions and culture. A higher indicator of spirituality as an aspect of family resilience among Russians is associated with a significantly higher choice of «Shimmering Space». In the Belarusian sample, the majority preference for «Living Space» and a rarer choice of «Invisible Space» are combined with lower indicators of the elimination of emotions and external well-being in the family than in the Russian sample.

The small number of differences in family resilience, family emotional communications in parental families and the absence of differences in the experience of close relationships allowed us to combine the Russian and Belarusian samples to identify family resilience profiles. The k-means cluster analysis, which took into account the data on the Family Resilience Scale and the Family Emotional Communications and Close Relationship Experience questionnaires, was conducted for the entire sample with normalization of data through z-scores.

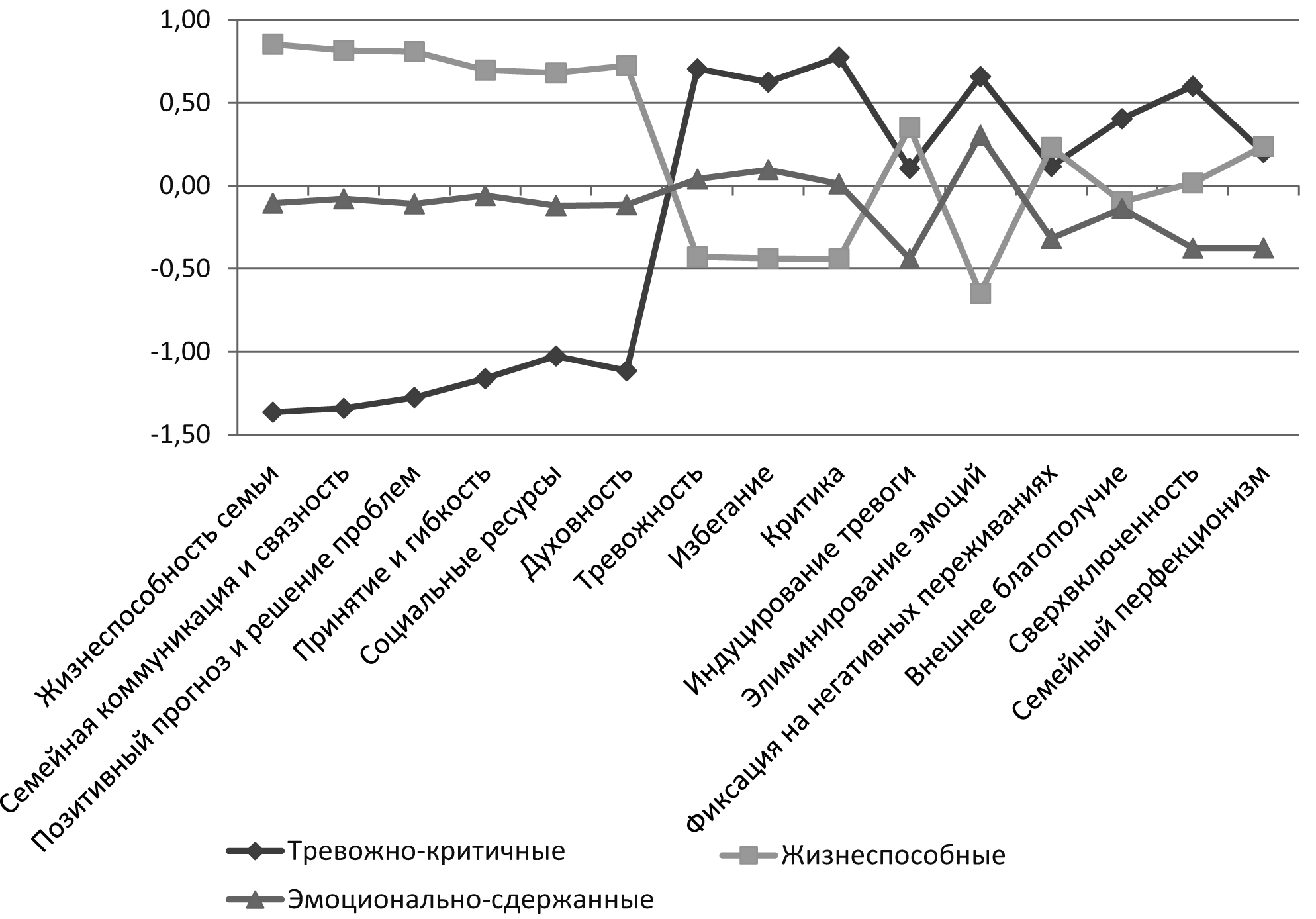

The first cluster (N = 179) included representatives of families with lower scores on all scales of family resilience and higher anxiety, avoidance, and criticism («anxious-critical»). The second cluster (N = 323) included individuals with high scores on family resilience and low scores on avoidance, anxiety, criticism, and elimination of emotions («viable»). The third cluster (N = 301) consists of representatives of families with average values of all characteristics of family resilience, anxiety, avoidance, criticism, low levels of overinvolvement, family perfectionism, but with a peak on elimination of emotions («emotionally restrained») (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Ratio of indicators by research methods in clusters (z-scores)

Fig. 1. Ratio of indicators by research methods in clusters (z-scores)

Representatives of Russian and Belarusian families were evenly distributed across the clusters (χ² = 0.130; p = 0.937). Differences were found in the ratings of the intensity of individual events (statistical effect at df = 5 F = 9.24; p = 0.002), which were significantly higher for representatives of Belarusian families. No significant differences were found when assessing the intensity of family-related events. No differences were found between the representatives of the different clusters according to gender (χ² = 0.912; p = 0.634); disability (χ² = 0.501; p = 0.778); presence of a disabled child in the family (χ² = 4.503; p = 0.105). However, the groups differed by family status (Table 3).

Table 3. Family statuses of representatives of different clusters

|

Family status |

Anxious-critical |

Viable |

Emotionally restrained |

χ², significance level |

|

Single |

60.3% |

38.1% |

40.5% |

χ² = 42.67

р = 0.000 |

|

In an unregistered marriage |

2.8% |

4.0% |

3.3% |

|

|

Married |

11.2% |

33.4% |

29.2% |

|

|

In a relationship |

22.9% |

20.1% |

22.9% |

|

|

Divorced |

1.7% |

4.0% |

4.0% |

|

|

No answer |

1.1% |

0.3% |

0,0% |

Significantly, 60.3 per cent of those in the «anxious-critical» cluster are not in a relationship, compared with no more than 40 per cent of those in the «viable» and «emotionally restrained» clusters. Only 11.2% of the «anxious-critical» are in a registered marriage, while among the «viable» and «emotionally restrained» more than a third or slightly less have such a marital status.

The groups also differed in the presence of children in their families (χ² = 22.94; p = 0.000). Only 12.1 per cent of the «anxious-critical» have children, whereas 42.7 per cent of the «viable» and 45.2 per cent of the «emotionally reserved» have children. The groups also differ in the number of children in their families (Table 4).

Table 4. Number of children in families of representatives of different clusters

|

Number of children in a family |

Anxious-critical |

Viable |

Emotionally restrained |

χ², significance level |

|

None |

27.0% |

38.9% |

34.1% |

χ² = 27.58

р = 0.000 |

|

One child |

14.9% |

38.8% |

46.3% |

|

|

Two children |

8.8% |

49.5% |

41.8% |

|

|

Many children |

8.3% |

41.7% |

50.0% |

Among the study participants without children, 27% are «anxious-critical», among members of families with two children, only 8.8%, and among representatives of large families, only 8.3%. The «viable» and «emotionally restrained» clusters make up the absolute majority of representatives of families with two or more children.

Significant differences were also found between the representatives of the three clusters in terms of the types of family situations that were seen as challenges (Table 5).

Table 5. Challenge situations in families of representatives of different clusters

|

Types of situations |

Anxious-critical |

Viable |

Emotionally restrained |

χ², significance level |

|

Not mentioned |

10.1% |

9.9% |

8.0% |

χ² = 29.363

р = 0.022 |

|

Illness |

16.2% |

11.2% |

14.0% |

|

|

Relationships |

36.3% |

21.1% |

29.4% |

|

|

Loss |

17.9% |

34.8% |

24.7% |

|

|

Material difficulties |

5.0% |

8.4% |

8.4% |

|

|

Global problems |

1.1% |

1.2% |

2.0% |

|

|

Intrapersonal |

0.6% |

0.6% |

0.7% |

|

|

Work/study problems |

0.6% |

0.6% |

0.7% |

|

|

Multiple difficulties |

12.3% |

12.1% |

12.0% |

|

|

Total |

100% |

100% |

100% |

Some family challenge situations were mentioned quite rarely, e.g. intrapersonal problems (depression, loss of meaning, etc.), but in terms of content they differed significantly from other situations and were singled out as a separate group. Some types of difficult situations are almost equally frequent in the different groups (intrapersonal problems, difficulties at work or in studies, multiple difficulties, of which relocation is an important part, as situations where several difficulties are interrelated at the same time). The biggest differences are problems in relationships with other relatives (mentioned by more than a third of the «anxious-critical», while representatives of other clusters mentioned it much less frequently) and loss of relatives. This situation was mentioned as a challenge by 17.9% of the «anxious-critical» and almost twice as many of the «viable». In other words, the resilience of families in this cluster manifests itself in the fact that the real challenges for them are the irreplaceable losses of loved ones. Problems in relationships with loved ones are secondary. Representatives of the «emotionally restrained» highlight problems in relationships with loved ones in almost 30 per cent of cases and losses in 24.7 per cent of cases.

There are significant differences between the groups according to the data from K. Adams’ projective technique. More than half of representatives of «viable» families choose «Living space», then «Shimmering space» and «Opaque space», and only a small part of them choose «Invisible space». At the same time, «Opaque» and «Living» spaces are both chosen by more than a third of the «anxious-critical» group. Among the representatives of the «emotionally restrained», most of them choose «Living space», with «Opaque space» taking second place (Table 6).

Table 6. Choice of illustrations of the technique «Spaces of Trees and Light» by representatives of different clusters

|

Illustrations |

Anxious-critical |

Viable |

Emotionally restrained |

χ², asymptotic significance |

|

1. Living space |

34.1% |

56.0% |

46.5% |

χ² = 59.4

р = 0.000 |

|

2. Shimmering space |

12.3% |

21.1% |

12.3% |

|

|

3. Opaque space |

36.3% |

18.9% |

26.6% |

|

|

4. Invisible space |

17.3% |

4.0% |

14.6% |

Thus, family resilience profiles differ quantitatively only in the parameters of family resilience (high – «viable», medium – «emotionally restrained», low – «anxious-critical»). Otherwise, each profile represents a qualitatively unique combination of parameters related to emotional communication and experiencing close relationships. The data from projective technique of K. Adams confirm the results of the questionnaires.

The data show that the differences between the representatives of the two ethnic groups with regard to the characteristics of family resilience, emotional communication within the family and the experience of close relationships are minimal. Regarding the individual vitality resources of the two samples, they are more significant (Table 7).

Table 7. Russian and Belarusian family representatives' vitality

|

Variables |

Russia (from 30 years old) M ± SD |

Belarus (from 30 years old) M ± SD |

Mann-Whitney U test |

Significance level |

|

Involvement |

18.2 ± 6.75 |

17.3 ± 5.9 |

30673.5 |

0.066 |

|

Control |

14.3 ± 5.5 |

13.0 ± 4.8 |

29439.0 |

0.011 |

|

Risk acceptance |

10.2 ± 3.9 |

9.7 ± 3.7 |

31569.5 |

0.184 |

|

vitality |

42.6 ± 14.9 |

40.0 ± 13.1 |

30100.5 |

0.031 |

|

|

Russia (from 31 years old) |

Belarus (from 31 years old) |

Mann-Whitney U test |

Significance level |

|

Involvement |

21. ± 5.6 |

20.1 ± 5.3 |

5360.0 |

0.174 |

|

Control |

14.4 ± 4.6 |

14.2 ± 4.0 |

5929.5 |

0.800 |

|

Risk acceptance |

11.0 ± 3.4 |

10.5 ± 3.6 |

5710.5 |

0.496 |

|

vitality |

46.5 ± 12.3 |

44.8 ± 11.4 |

5538.0 |

0.311 |

In contrast to the Belarusian sample, the younger age group of the Russian sample shows higher levels of vitality in the control and general vitality parameters. No such differences were found in two subsamples of Russians and older Belarusians. This is in line with data from previous studies [Odintsova, 2019]. In general, the data obtained on family resilience and individual vitality require a thorough understanding.

Discussion

The study revealed a significant similarity of Russian and Belarusian family resilience profiles, manifested in the even distribution of both countries' representatives in clusters. We can say that the family resilience profiles of Russian and Belarusian families are similar due to the absence of differences in the indicators of family resilience between the representatives of the two countries and their even distribution in the clusters of «anxious-critical», «viable» and «emotionally restrained».

The similarity of family resilience, emotional communication, and experience of close relationships among representatives of Russian and Belarusian families, along with differences in individual vitality revealed only among younger subgroups partially confirm our hypothesis. Some of our assumptions concerning the cultural and historical origin of the revealed differences were confirmed. Representatives of the older age groups of Russians and Belarusians grew up and were formed as individuals in a common cultural-historical space, unlike the younger age groups whose lives were in the post-USSR period [Odintsova, 2019].

It is also reasonable to assume that the differences in vitality of young people in the Russian and Belarusian samples are the result of interaction between family resilience and specific historical and social conditions in the structure of the research participants' social development situation. It is also possible that the tragic history of Belarus, which is more pronounced in comparison to that of Russia, is a mediator of a higher assessment of the intensity of a negative event, which is itself a sign of lower vitality. This conclusion is indirectly confirmed by the study of M.N. Efremenkova and co-authors [Efremenkova, 2023], who showed that in Belarusian students’ social perceptions the present of their country is much more connected with the past than in the case of Russian students, who in their turn make a stronger connection between the present of Russia and its future.

It is likely that family spirituality as a resource for family resilience is also more pronounced in the Russian sample, as Russians have a more distinct ethno-confessional identity, unlike Belarus, where two confessions (Catholicism and Orthodoxy) have been in conflict for centuries. At the same time, Russian families are more characterized by the elimination of emotions and the pursuit of external well-being, which is confirmed by the fact that Russians are more likely to choose a drawing that symbolizes doubt, fear of the family and rejection by others. Further research is needed into the reasons for the combination of these characteristics.

Conclusion

The data obtained confirmed our hypothesis about the greater similarity of family resilience among representatives of the two ethnic groups and more marked differences in individual vitality among adolescents. It is fair to say that the similarity of peoples' historical fates determines the similarity of historical narratives, which, mediated by family history, are reflected in family narratives and become an important factor in the formation of family resilience. However, individual vitality is also influenced by many specific historical and social factors, reflected in differences in this characteristic between Russian and Belarusian youth, with no significant differences between older age groups. Perhaps the reason is that older generations of Russians and Belarusians are more united by the country's common history than youth.

The family resilience profiles identified in our study can be widely used in cross-cultural family studies to characterize family resilience and the social situation of family personal development, as well as in individual and family counseling. The projective technique according to K. Adams provides important information to characterize the social situation more complete. In general, the obtained data testify to complex interrelations of family, concrete-historical and social factors of social developmental situation in which vitality is formed.

Limitations of the study include a small overall sample size and a relatively small sample of older Belarusians. It is desirable to conduct further research in this direction on age-balanced samples. Clarification of the content of the historical narrative in the consciousness of the representatives of the studied peoples is also necessary for cross-cultural research.

Findings

The study revealed a significant similarity in the resilience profiles of Russian and Belarusian families, largely explained by the two nations' common history and similar cultures. Differences emerged in spirituality as a resource for family resilience, elimination of emotions, and tendency to demonstrate the family's external well-being. Belarusians rated negative life events higher. Older Russians and Belarusians do not differ in their individual vitality, whereas such differences are pronounced between younger Russian and Belarusian samples.

The revealed differences in how the participants with different family resilience profiles perceived their childhood situation are significant in the context of psychological support for families in general and individual family members in particular.