Introduction

Programming has been taught in schools for more than half a century. The emphasis has shifted over time, but the focus has always been on introducing students to the world of digital systems and teaching them how to use digital technologies. Soviet academician A.P. Ershov, one of the founders of computer science education in USSR, wrote about programming as a “universal second literacy” in the early 1980s – even then, computers and programming were seen as a way to enhance children’s cognitive development (Ershov, 1983). The world-famous researcher and advocate of teaching children programming, Seymour Papert, has formulated the following educational principle (Papert, 1980): the way we teach not only programming but also other subjects must change. Instead of providing students with ready-made knowledge, they should be encouraged to build their own understanding through independent exploration. A programmable computer can be an invaluable tool in this process.

Papert’s pedagogical innovation, constructionism, was a response to the traditional approach to teaching programming, which he called “instructionism”. This approach involves learning through teacher-led instructions. Instead, Papert proposed creating situations in which children could independently construct new knowledge. To study the processes of child development, Papert and his colleagues from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology created the LOGO programming language. This language allows children to draw figures on a computer screen by programming the movement of a virtual turtle.

In the 1980s and 1990s, researchers both abroad and in Russia showed that Papert’s approach to teaching programming and computer science had limitations (Pea et al., 1985), as well as in the broader context of child development (Davydov, Rubtsov, 1990). However, this does not diminish the revolution that his approach has made in educational psychology. It provides a unique example of creating conditions for a child’s independent learning activities. The way Papert suggested working and learning on a computer is more like a game or a bricolage, rather than a systematic learning of a tool (Turkle, Papert, 1990).

Despite the skepticism of many researchers and educators, this technique has been continued in school LEGO robotics (Resnik et al., 1988) and programming in visual environments. The most popular of these is Scratch1, which has become ubiquitous. Often, elementary school students’ first steps in programming begin with Scratch or LEGO Mindstorms robots. From 2022, in Russia, analogues of these products flooded schools (Ovsyannikov et al., 2023). Constructionism pedagogy also finds continuation in “fabs” – digital production environments – through the creation of material embodiments of digital models (LaParde, Lassiter, 2023).

The popularity of constructionism is not a coincidence and is based on the evolution of computers and the way users interact with them. Along with the rise of the mass culture of consumer society and the increasing popularity of digital devices, there has been a decrease in the demand for specialized knowledge and computer science background among users. This is not without influence from Papert’s ideas, as independent user exploration through an accessible interface and trial-and-error actions have become the primary mode of interaction. The motto “Don’t Make the User Think” has been widely adopted by digital system interface designers for over 30 years (Krug, 2000).

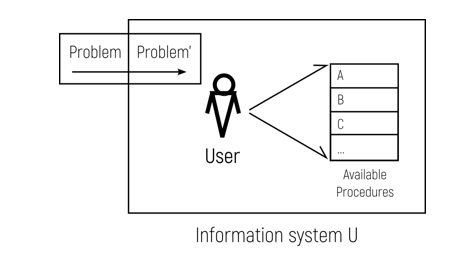

An analysis of the development of operating systems reveals that users of modern computers and smartphones have been offered a limited range of specific actions or procedures, allowing them to perform only those actions prescribed by the system developer (Kouryachy, 2004). These procedural human-computer systems rely on independent testing based on a graphical interface and reinforcement of correct user behavior when manipulating virtual objects. This reduces the need for prior knowledge and self-learning is based on a constructionism approach.

From a psychological perspective, this type of system provides the user with a limited range of operations using fixed sign systems designed to address specific practical tasks. At the same time, the reconstruction of the underlying principles of sign systems and the proposed operations remain outside the user’s scope, and the user often loses sight of the need to conceptualize and model the subject matter of the objects they are working with (Davydov, Rubtsov, 1990).

The idea that schools should train literate consumers has been discussed many times in pedagogical communities and widely. Modern digital technologies can only help such schools, as the need to teach children specifically how to use these programs is decreasing every year. Children are in a digital environment from birth and, as “natives”, they naturally master new interfaces and sort through available operations (Palfrey, Gasser, 2011). At the same time, it becomes increasingly difficult for them to avoid the patterns and limitations of thinking that modern procedural systems hide (Fedoseev, 2013). The consequences of this are epistemological relativism, where feedback takes the place of error (Turkle, Parept, 1990), and the spread of phenomena like “technomagic” among users – forms of ignorance where digital systems are no longer seen as knowable control devices.

In contrast to the consumer-oriented approach, prominent educators, including Papert, Ershov, and V.V. Davydov, argued that schools should focus on developing children’s thinking. This perspective is reflected in thought-activity pedagogy and the vision for the future of education (Gromyko, Rubtsov, Margolis, 2020). Building on Davydov’s ideas, Russian educators and psychologists have developed requirements for computer-assisted learning technologies that prioritize the principle of computer modeling of activity (Davydov, Rubtsov, 1990) and the development of the culture of thinking (Zhegalin, 2007).

Is it possible to maintain the student’s subjectivity in education, characteristic of constructionist pedagogy, while also overcoming the limitations of modern digital systems? How can we move beyond the dichotomy between the formal-logical instructionist approach to teaching programming and the limitations of constructionism based on empirical thinking? For example, by working with ideal models? Can we shift from rote memorization to modeling-based learning using programming and digital systems, similar to V.V. Davydov’s work on the formation of the concept of number or A.A. Ustilovskaya’s work with geometric objects (Ustilovskaya, 2008)?

This article explores the theoretical foundations of this issue and proposes a potential approach to addressing the limitations of constructionism in the digital learning of schoolchildren.

Seymour Papert’s pedagogical approach

In the 1980s, the primary method of working on a computer involved programming using text-based languages, which assumed the performing specific operations through the command line. This form of programming required a strong mathematical background, including an understanding of basic algebra (variables and operations), functional analysis (functions and recursion), and formal logic for theorem proving (logical conditions and sequential program execution), among other concepts. Due to these requirements, the number of students who successfully mastered computer science was limited. Seymour Papert, in his humanitarian effort to promote computer literacy for the masses, introduced the concept of constructionism2 in his book “Mindstorms” (Papert, 1980). Developing the ideas of Jean Piaget’s constructivism, Seymour Papert emphasized the importance of students’ simple interactions with virtual objects and their creation of new objects. This allowed students to explore the virtual environment and develop more complex operations. Through this process, students constructed the subject of their work and gained knowledge about it.

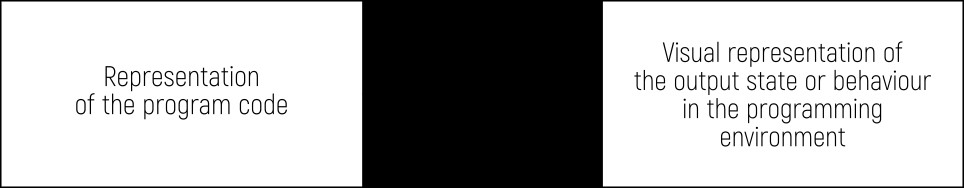

This was made possible thanks to Papert’s key pedagogical technique, which was implemented in the LOGO visual programming environment – visual construction. This technique ensures a direct representation of the commands in the programming language to the results of their execution (see Fig. 1), in the form of a trajectory drawn by the turtle on the screen following the commands in the program.

The user could execute commands and see the changes on the screen at the same time. This approach allowed the child to create his own learning process. Over time, he could add more complex operations to elementary ones and form various concepts of structural programming. He could also learn the basics of imperative programming, algorithmic and constructive thinking.

The LOGO language offered by Papert provided new opportunities for teachers. They could give children the possibility to create their own virtual world and designate specific actions for the turtle in the program using words. Although the object was represented on the computer screen in a material way, this approach helped children reach ideal meanings about programming. The ‘TRIANGLE’ command, created by the child and consisting of simpler operations for drawing segments, reproduced a triangle on the computer screen according to clear and strict mathematical rules. In this way, symbolic representations in the program code and on the screen began to represent the key characteristics of ideal objects (see Fig. 2). Building on this elementary step of independently constructing and naming objects, Papert proposed building more complex ideal objects through induction.

The constructionist approach implemented in LOGO was developed through further experimental pedagogical practices. M. Beynon proposed expanding work with graphic objects to include more complex operations for constructing dynamic objects, in order to create an ideal representation of processes (Beynon, 2017). As part of creating tangible objects in digital production spaces called “fabs”, researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology suggested introducing primary ideas about ontologies to schoolchildren (LaParde, Lassiter, 2023).

Nevertheless, the widespread use of LOGO in schools has not only aroused enthusiasm among teachers, but also sparked criticism. This criticism has pointed out, among other things, the limitations of the constructionism approach to teaching programming and the development of programming abilities (Pea et al., 1985). The main areas of concern include the lack of influence of LOGO on the development of basic programmer skills such as planning and problem-solving, as well as difficulties transferring programming knowledge and skills to other learning contexts, including professional settings.

However, one of the most significant aspects is the crucial role of the teacher in conducting these classes. S. Papert emphasized the importance of training teachers who can guide children as they embark on the journey of constructing new knowledge. Such aspects of the teacher’s work as comparing the ideal content with the context of the visual environment and working with an ideal representation of a computer system are highlighted. Designing one’s own actions based on elementary operations when working with a specific subject area and practical task involves students entering the modeling process, which puts high demands on both the digital system and the teacher (Rubtsov, Margolis, Pazhitnov, 1987).

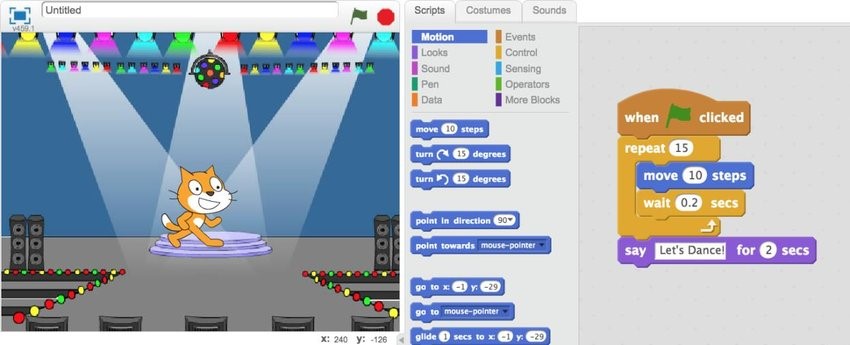

Today, Paper’s ideas have been implemented not only in elementary schools, but also in secondary schools, where students use the Scratch visual programming environment to create cartoons, simple video games, as well as the LEGO Mindstorms plastic robots, which they program to perform simple actions, such as riding a line (Resnick et al., 1988). The Scratch environment implements the same basic principle as the LOGO programming language, but with a more modern graphical interface (see Fig. 3). Instead of writing code, students compose programs by selecting and combining existing blocks. This makes the programming process easier and more intuitive for students. From a psychological perspective, this change was fundamental. Instead of thinking about and introducing new concepts based on existing ones (as in the example of drawing a triangle, which involved three movements and turns), students started to visually combine symbols that represent individual operations on objects into a specific sign system of words, icons, and numerical parameters.

This interface is designed in the tradition of modern digital systems, where users work with graphical objects and select and move them using the mouse. For children who are accustomed to graphical and tactile interfaces on computer and smartphone screens from a young age, this method of creating programs may be more appealing.

However, the issue of sign naturalization, which arises from operating with objects without considering the underlying structure of actions and essential ideal characteristics of these objects, requires more detailed examination (Ustilovskaya, 2008). This is prompted, among other factors, by the visually rich interfaces that we encounter in modern information systems. Let’s take a closer look at this phenomenon of sign naturalization when working with these systems.

Sign naturalization in modern information systems

The phenomenon of sign naturalization is studied in educational psychology as a way to distinguish between the development of specific skills in solving practical problems and the student’s ability to restore the initial relationships and ideal characteristics underlying these skills (Davydov, 1996; Medvedev, 2010). When working in a given system of skills, naturalization (or embodiment) occurs if there is no need to reconstruct the structure, laws, and ideal representations associated with those skills. In other words, when working in sign systems, students may operate on signs without having to restore their original meaning.

In a pedagogical context, naturalization itself may be the first step in overcoming verbalization, as shown by the example of students studying geometry (Ustilovskaya, 2008). Students must first perform substantive actions with drawings in order to move beyond simple pronunciation. However, in order to develop generalized methods of action, teachers must specifically organize the process of overcoming naturalization in order to achieve the ideal relationships that characterize geometric objects.

At the moment, when it comes to working with information systems, the problem of verbalization is not as significant3, because even novice users can perform simple operations in the system, which lead to visible changes. However, due to the richness of the interface and the variety of plots (for example, in Scratch or LEGO), children may fall into the trap of sign naturalization: objects on the screen appear to be real objects – they begin to be perceived as they look, without considering the ideal content behind them.

Sign naturalization is a common phenomenon in modern information systems. Since the advent of the LOGO, there has been a revolution in user interaction with systems. Most end-user systems, whether they are personal computers or smartphones, can be described as procedural (Kouryachy, 2008). This concerns the very principle of how users operate them (see Fig. 4). If for a professional programmer, computer programming is a set of tools based on which they design the environment necessary to solve specific problems, then users in a procedural system can only solve tasks that are covered by a list of possible operations in the system. These operations are embedded in the interface and can be combined to perform certain actions. The composition of such systems is not transparent to users, so their behavior is predictable only when they perform standard actions.

An interesting effect of using these systems is that a given set of procedures often not only determines how to solve a problem, but also significantly influences the user’s initial task statement – the external task becomes adapted to the capabilities of the system. For example, when using a popular text editor, the user edits a document at the level of its external representation, as if it were created on paper. However, the user often overlooks many unique features of digital documents, such as the separation of information, the various forms of presentation, and the use of automated tools like numbering bibliographies and working with dictionaries.

A striking feature of modern information systems with graphical interface is the use of special icons that resemble real-world objects. These icons allow users to perform operations without relying on their knowledge of the system’s inner workings. For example, a desktop appears on the screen with “folders” and “documents” that can be stored, sent to the cloud, or moved to “trash”. These actions are familiar to users who have experience with real-world files and folders.

Sign naturalization allows you to perform available operations independently and form simple actions from them. You can see the immediate result of your steps and transform objects. This is useful for simple operations that lead to clear results, as well as for learning the available operations in a system. This corresponds to the idea of constructionism. It is not surprising that designers of commercial products have used this technique to create interfaces that are easy to understand and use. They create a sign naturalization for users, allowing them to quickly master and use the product. This speeds up user actions and leads to automatism (Krug, 2000).

From a psychological perspective, some important limitations of procedural systems based on sign naturalization mechanisms can be noted. This includes the user’s disclaimer of responsibility for their actions – anything can go wrong: faulty hardware, buggy programs, or incompetent programmers. The widespread adoption of procedural systems is linked to commercialization and the transformation of users into consumers – the consumer receives a finished product and doesn’t have to deal with issues caused, among other things, by their own mistakes.

Another limitation is related to the potential for developing the user’s thinking. When working with ready-made procedures, templates, and wizards, users may fail to understand the limitations of the system and the modeling or design activities that are characteristic of instrumental use by programmers. M. Wertheimer has also noted how the habit of consistently acting step by step according to a learned pattern hinders the development of thinking (Wertheimer, 1987). It is also possible to detect limitations in users’ ability to detect ideal representations and retain these representations when using interfaces typical of modern procedural systems (Fedoseev, 2013).

Sign naturalization is a serious limitation in teaching programming. Due to the immutability and procedural nature of these systems, as well as the inability to reconfigure or change the activity model, users and novice programmers are limited in their ability to select the ideal computer (or notional machine) for their needs. For example, the turtle in Seymour Papert's LOGO language and the Scratch language cannot be modified by users, and these systems are not designed to allow users to “look under the hood” and understand the internal workings of the system. Researchers have identified the allocation of a notional machine as a key pedagogical goal when learning programming methods (Munasinghe et al., 2023; Papert, 1980; Sorva, 2013). However, this goal is often not achievable due to the limitations of current procedural systems.

V.V. Davydov, V.V. Rubtsov and other researchers (Davydov, Rubtsov, 1990) analyzed the approach of S. Papert and found that in his pedagogical system, the main content that students master is reduced to performing operations specified by the organization of a computer system. This corresponds to operative control in Davydov's developmental education. Other learning activities, such as highlighting the initial relationships of the system, modeling, and transforming models, are less represented in Papert’s system. Furthermore, following the approach of J. Piaget, Papert equates the operational form of action and the content of the action, which have a definite meaning for students. According to Davydov and Rubtsov (Davidov, Rubtsov, 1990), if we take into account the interchangeability of educational actions and operations, it becomes very difficult to define the composition of operations unambiguously.

The S. Papert’s game-pedagogical approach is criticized by some researchers and developers of educational video games, for example, J. Bogost (Bogost, 2010). The student, working according to the S. Papert system, takes for granted the presented image of objects and a set of operations in a specific computer system. In this learning system, the student is not put in a situation of building a sign relationship and creating models of the essential characteristics of the computing system used in a given programming language. It is this type of model that may be the most fundamental and important, since it allows students to answer questions about why they use programmable computing systems and how they interfere with the regulation of automated physical processes. That is, computer-based programmable computing systems could become a means of organizing student activities.

Thus, when working with information systems and teaching programming, it is necessary to use tools and pedagogical practices to overcome the sign naturalization and create situations that promote students’ thinking development. Let us take a closer look at a possible approach to solving this problem based on the works of V.V. Davydov, V.V. Rubtsov, and Yu.V. Gromyko (Gromyko, Prosekin, 2024; Gromyko et al., 2020).

Overcoming the sign naturalization

In the works of Russian scholars V.V. Davydov, V.V. Rubtsov, and Yu.V. Gromyko, the process of overcoming limitations of constructionism and sign naturalization is linked to the students’ actions of modeling. Computer modeling of activity can create conditions for identifying and highlighting essential characteristics of objects (Davydov, Rubtsov, 1990). By using specific actions and tools, overcoming sign naturalization forms a fundamental step toward shaping children’s thinking (Ustilovskaya, 2008). This requires going beyond the limits of excessive illustrativity and persuasion in order to reveal mental structures embedded within language (Gromyko, 2023).

V.V. Davydov developed an educational system that also encourages students to acquire knowledge “in a ready-made form”, as S. Papert argued. However, unlike Papert's constructionism, Davydov’s approach is based on the use of specific activities that allow students to understand the origins of knowledge, such as the concept of number and phoneme. To master these concepts, students must engage in hands-on activities that help them understand their origins. Davydov developed a methodological system for the formation of a primary school student’s educational activity. This system consists of independent learning activities that the student performs: specific subject actions to identify the initial relationship of the system being studied, actions to model this relationship, actions to transform the model in order to study this relationship, solving specific problems based on the development of a general solution method, and actions to control and evaluate the development of this general method for solving learning problems. Through these educational activities, young students learn the content of a concept.

Overcoming sign naturalization is possible by identifying the essential characteristics of an object and constructing proper sign systems that define its ideal representation within the framework of a human-machine activity system. This process has been studied by Russian psychologists in the context of forming a generalized mode of action among schoolchildren through students’ independent model construction as a result of cyclic movement from objective actions to ideal representations by introducing new symbols and words (Davydov, Andronov, 1997). L.V. Bertsfai’s (Davydov, 1996) and A.M. Medvedev’s (Medvedev, 2010) experiments consider the process of transition from mastering individual operations to mastering generalized abilities through the formation of students’ own sign representations. By applying this approach to working with an information system, students can recreate the ideal scenario of activity in which a programmed system is used. This allows them to discover the limitations of existing models or propose their own solutions.

From the point of view of thought-activity pedagogy, theory and practice of developmental education, the student should be given the task of modeling the initial relationship of the mastered system of programmable computing. In this case, the aim of such modeling is the relationship of a notional machine to a programmable, regulated system of automated material processes in various practical contexts. It is this form of modeling that will allow the student to transform computational thinking (Grover, Pea, 2013) into a means of working with an activity system that includes a computer. Such modeling makes it possible to turn signs into the means of expression. For instance, the focus of work in a programming game should not be so much on constructing programs from pre-built blocks or elements of a programming language. Rather, it should be on understanding the principles that the developer has laid down in such a framework, discovering the modeling relationships in a given programming language, and exploring its limitations. Additionally, it is important to go beyond these principles when tackling more complex practical problems. This includes creating new and more advanced models.

This approach can also benefit from the use of specialized tools, such as simulation modeling environments (Zhegalin, 2007) and agent-based modeling systems within the framework of the digital-cognitive approach (Gromyko, 2023). Additionally, artificial intelligence systems and cyber-physical systems have great potential for modeling education, as they are associated with addressing uncertainties at the intersection of deterministic digital systems and stochastic physical realities. Working with cyber-physical systems that involve both digital and physical processes offers a more comprehensive understanding of modeling. These systems form the foundation for a new meta-disciplinary field known as activity-based cyber-physics, which is currently being developed in Russia through the National Cyber-physical Platform (Fedoseev, 2023), based on a network of technology communities (Andryushkov, 2023). Working in these systems involves students directly participating in the creation of a model of the desired system, and only then moving on to creating a program (process management or digital simulation) based on that model.

Speaking about the exceptional significance of the principles proposed within the framework of constructionism for shaping the educational subjectivity of schoolchildren and their autonomous learning activities in situations organized by teachers, it is worth noting the great potential of play-based learning forms (Fedoseev et al., 2025; Bogost, 2010), especially when involving participants in complex activities such as research activity (Fedoseev, Vdovenko, 2014). Integrating game tools that simulate and organize reflective communication and student engagement can be a significant step towards implementing the pedagogical approaches outlined in this article.

Conclusion

The article discusses the issue of sign naturalization in teaching programming and work with information systems in general. This issue has become particularly relevant due to the widespread transition from traditional teaching methods to constructionism, proposed by S. Papert, and implemented in modern software and educational environments such as Scratch, as well as in widely used information systems.

The approach discussed in the article, which aims to overcome the sign naturalization and is associated with the restoration of the original modeling relationship in the system, makes it possible to create an alternative environment for student thinking development when working in digital environments and learning programming. When implemented in the educational process, this approach can help to put into practice ideas from the school of the future, which are based on the development of student ways of thinking, communication, and action through immersion in design, research, and other leading forms of cultural activity.

In order to identify the psychological mechanisms for overcoming the sign naturalization of modern digital systems and environments, and to create conditions for implementing appropriate pedagogical practices in junior and secondary schools, further psychological and pedagogical research is needed. This includes experimental confirmations of certain approaches outlined in this article.

1 https://scratch.mit.edu

2 It is important not to confuse S. Papert's constructionism with J. Piaget's constructivism.

3 Due to the increasing popularity of dialog-based interfaces based on artificial intelligence tools, and their partial replacement of graphical interfaces, the issue of verbalization in information systems may become more relevant.