Introduction

In the first part of this article, we proposed a reference mediation model where, in line with the cultural-historical approach, we described the experience of schoolchildren's development and the establishment of new, activity-related formations, i.e., higher abilities, including the ability to engage in research activities that involve digital devices (Pavlovsky et al., 2024).

The main characteristics of a child's developmental step are, according to the language of the mediation model, that he or she masters, with the help of an adult mediator, a new way of acting, thereby transforming an external stimulus into an internal activity formation. An external means-stimulus, a psychological tool, turns into an internalized method of action, meaningful and reflected on, which allows it to be appropriated and become part of an individual’s personal organic structure, a new “functional organ.” As noted by Elkonin (Elkonin, 2010, p. 233), a stimulus that used to be external for a person, becomes an internal resource, and the sign transforms into a means for constructing actions.

We put forward a hypothesis that involving students – participants of the “Schoolchildren — Scientific Volunteers” project (hereafter referred to as SSV) in research activities and integrating digital tools into these activities would contribute to developing their desired investigative vision, forming a new functional organ.

To verify it, upon completing the project, semi-structured interviews were conducted with different groups of participants from various regions (six groups); 70 schoolchildren took part in a questionnaire survey. Additionally, expert interviews were held with adult mentors and researchers (6 in total). The interviews comprised some benchmark questions aimed at encouraging reflection. We sought to address pupils’ reflective experiences regarding their participation in the project. Overall, more than 100 project participants took part in surveys in various formats.

Sign and digital

To understand the specifics of the new mediating link represented by digital tools in the mediation model, it's essential to recall the fundamental features of signs understood as psychological tools under the cultural-historical approach (hereinafter referred to as CHA). What are the characteristics of sign-symbol mediation? What distinguishes classical sign-symbol psychological tools? (See also Vygotsky (1982, 1984), Pavlenko (2020), Polyakov (2022), Khoziev (2005), Elkonin (2010, 2016), Smirnov (2023a).

1.Self-directedness. L.S. Vygotsky strongly emphasized that a psychological tool primarily focuses on an individual (a child) who masters it and, through this mastery, gains control over oneself.1

2.Social and activity-based nature. Psychological tools are initially developed in a social environment external to an individual.2 First, mental function is manifested externally, in social interactions outside an individual, evolving as a "functional organ" of activity. Basically, there are no localized separate "higher mental functions", inherently present within individuals. All such functions develop through engagement in activities and become integral parts or new formations in an activity-based, functional body of a human personality (an organ of walking, writing, counting, reading, etc.)

3.Engagement in an act of child – adult interaction. Developing his teacher’s ideas, D.B. Elkonin adopted the figure of a significant “social adult” (that was mentioned but not model-integrated by L.S. Vygotsky, who did not complete the model). A psychological tool does not exist on its own. It does not possess the properties of agency or subjectivity. It is always presented and transferred to a child through the hands, voice, and body of a significant adult. The adult demonstrates to a child how to perform actions using this psychological tool. It is the adult who integrates the psychological tool into an act of communication with the child, carrying out joint mediating action together with the child. In this regard, B.D. Elkonin followed D.B. Elkonin's lead, focusing more on the joint construction of intermediary activity by both adults and children rather than the mediating role of the sign-tool (Elkonin, 1994; Elkonin, 2016).

4. The sign nature of the psychological tool. Through the mediation by an adult-intermediary, a child regulates his/her behavior specifically through a "sign operation"—by means of speech, mumbling, gestures, verbal expression, constantly keeping the adult in the focus of attention to show how he / she is eating porridge, building a house with blocks, or drawing scribbles on paper. This sign action is already directed at oneself, towards one's own behavior. The child reinforces one’s object-related action with a sign action intertwined with the object-related one. Parallel to the reality of tool activities, a sign reality emerges. It is within this sign reality that speech arises, making humans. As emphasized by L.S. Vygotsky, it is precisely this phenomenon that makes humans free, independent of the natural visual field. The more developed is child's speech, the freer and more purposeful his/her object-directed actions become (Vygotsky, 1984, pp. 85–86)3.

Thus, the main features highlighted by L.S. Vygotsky when describing signs as psychological tools include their orientation toward an individual (a child), enabling him or her to master their own behavior through these tools. Furthermore, as repeatedly stressed by L.S. Vygotsky, once embedded in the structure of mental activity, the sign alters, restructures, and transforms this very structure. These are the key points4.

Now, however, our task is to examine the "digital" as a special sign-tool mediating human behavior (particularly, behavior of schoolchildren). What distinguishes the digital (gadgets, devices, or instruments) as a new type of sign-tools from familiar sign forms? Can we identify the constructive role of the digital as a new psychological tool of mediation in an act of development? What is the specifics of the mediating role of the digital5?

For example, O.V. Rubtsova argues that by L.S. Vygotsky, the concepts of 'sign' and 'tool' were distinctly separated: the tool acted externally relative to the child, while the sign as a psychological tool was oriented inwardly, towards the self. According to Rubtsova, however, the digital combines both sign and tool features. Take a mobile phone, for example. Sometimes, it serves as a tool (for sending electronic messages); on other occasions, it acts as a sign (mediating cognitive processes, e.g., social media interactions). Moreover, transitions between functioning as a sign and as a tool are fast, seamless, and habitual for users (Rubtsova, 2019, p. 122).

First of all, note that the digital is indeed a sign, albeit special. It a sign of a sign, virtual sign form. It designates another, virtual reality, virtual objects rather than conventional social things, actions, people, or relationships. The nature of the digital is virtual. It is this inherent virtual nature that entails profound implications regarding its role as a mediator of human actions, particularly those of children, whose higher-order abilities are underdeveloped.

Let’s highlight, purely conceptually, the distinctive features specifying the mediating role of the digital based on the classical understanding of the role of psychological tools outlined above.

1. Changing an orientation vector. Numerous studies on the impact of the digital (gadgets and internet usage) on children and adolescents — groups that lack sufficient skills and experience in self-regulation and control over their behavior — demonstrate that the digital, being active and directed towards a child, is not taken by a child as a psychological tool aimed inwardly. Instead, it guides a child outwardly, towards the digital environment. Therefore, rather than becoming a sign-tool facilitating the acquisition of the modes of action, the digital deprives children of the power required for a mode of action and offer ready-made solutions. Children do not need to develop self-control; they simply adopt pre-programmed patterns of behavior embedded in a gadget (see detailed analysis in Smirnov, 2023a).

2. Virtual, transformed nature. The digital, and virtual reality in general, constitute a transformed form of the reality. It certainly exists as a reality, but a transformed reality. It is fully real, indeed; yet, it is a transformed reality substituting the other, primordial, activity-based reality. Just as the money form of value substitutes the actual value of goods, as Karl Marx demonstrated (Smirnov, 2023b).

In other words, digital reality lacks its own "social power," as L.S. Vygotsky put it. It does not act as a form of authentic social relations but rather substitutes them with virtual forms that seem real and genuine to someone immersed in the virtual sphere. Consequently, it creates an illusion of a comprehensive reality.

3. Digital as the habitat. Traditional tools within the CHP framework, for example, spoons used by babies learning to eat cereals or any other items (pens, forks, hammers, mechanisms) were invented by adults — people with experience, relative to whom a new human being is a child, not a self-standing, grown-up individual. The digital, on the contrary, enters children's lives on par with the adults and it happens prematurely, often starting in the first months of life alongside toys and household items6. Thus, for children, the digital represents an omnipresent habitat rather than merely a sign-tool. Unlike tools, however, habitat cannot be mastered; one enters it and adapts to its rules. The digital surrounds children independently of adults, simply due to the fact of its presence.

Therefore, in this context, we cannot isolate the communicative act wherein an adult provides a pattern of tool action along with the implicit mode of action. Frequently, the digital envelopes the habitats of both an adult and a child, so there is no clear carrier of the pattern of action.

4. Substituting humans with virtual signs. Ultimately, these characteristics of the digital as a sign leads to the displacement not only of an adult, the other individual but of any other social reality. The substitution process commenced prior to the advent of the digital. Sign mediation, natural for the cultural evolution of humans and described within the CHP tradition, obtains its historical continuation. Similarly, further transformations of transformed forms will continue as illustrated by the replacement of paper money with virtual equivalents. The process of transformation takes place not in the minds of particular individuals but in their actual life, just the forms of life are getting increasingly more virtual.

In view of the above features of the psychological tool, it is essential to consider the digital not as the environment and power which strips children (and humans in general) of their actor’s position, but rather as a sign capable of transforming hybrid digital environment into a meaningful field for constructing new, collective, mediated actions, when the digital becomes an assistant in creating ‘try-and-explore scenarios’ for diverse developmental situations (Elkonin, 2023a; Elkonin, 2023b)7.

Therefore, the issue does not lie in the digital per se. Everything depends on the original set-up of educative research: is it geared towards employing the digital as a means of development, or does it merely consider using it as a tool?

Given the risks associated with delegating tasks to digital assistants, especially generative models, reflective tasks, the level of goal-orientation and mindful use of such aids are mandatory. Otherwise, digital devices will dominate the activities and script the behavior of both learners and even researchers. Alternatively, humans could assume an active role, leveraging digital tools effectively to enhance human capabilities.

B.D. Elkonin noted this difference in one of his interviews:

"First example. A mother pushes her five- to six-month-old baby in a stroller. To allow herself to talk on the phone without distraction, she turns on a screen for the child, engrossing him completely so he doesn’t bother her with his needs. What's happening here first and foremost... it's not the child controlling the device, but the device controlling the child... It's not the seven-month-old infant managing images with his eyes, eye movements, comprehension, or perception; rather, the pictures dictate the movement of the child's gaze...

Another example... An experiment was conducted at Moscow State University of Psychology and Education when a fairy tale cartoon was demonstrated on a tablet and the participants could interactively manipulate the imagery. Three groups of children were identified: the first group simply scrolled through; the second group did something with the image, such as changing leaf colors to make them brighter, and so on. And the third group actively influenced the climax, i.e., the intrigue, the central event of the storyline, modifying the situation altogether…These children played with the storyline, working with the focal point of the plot. For this particular group, the "digital" became a means to amplify their comprehension and experience of the fairy tale (Elkonin, 2023a, p. 225).

Digital in the SSV project

How was the digital used in the SSV Project?

First, gadgets were employed as the tools with built-in functionalities to photograph plants and mushrooms and identify species.

Second, some schoolchildren compiled digital cards to record data about natural objects. Initially, a child observed the plant directly, then entered systematic botanical information onto the card.

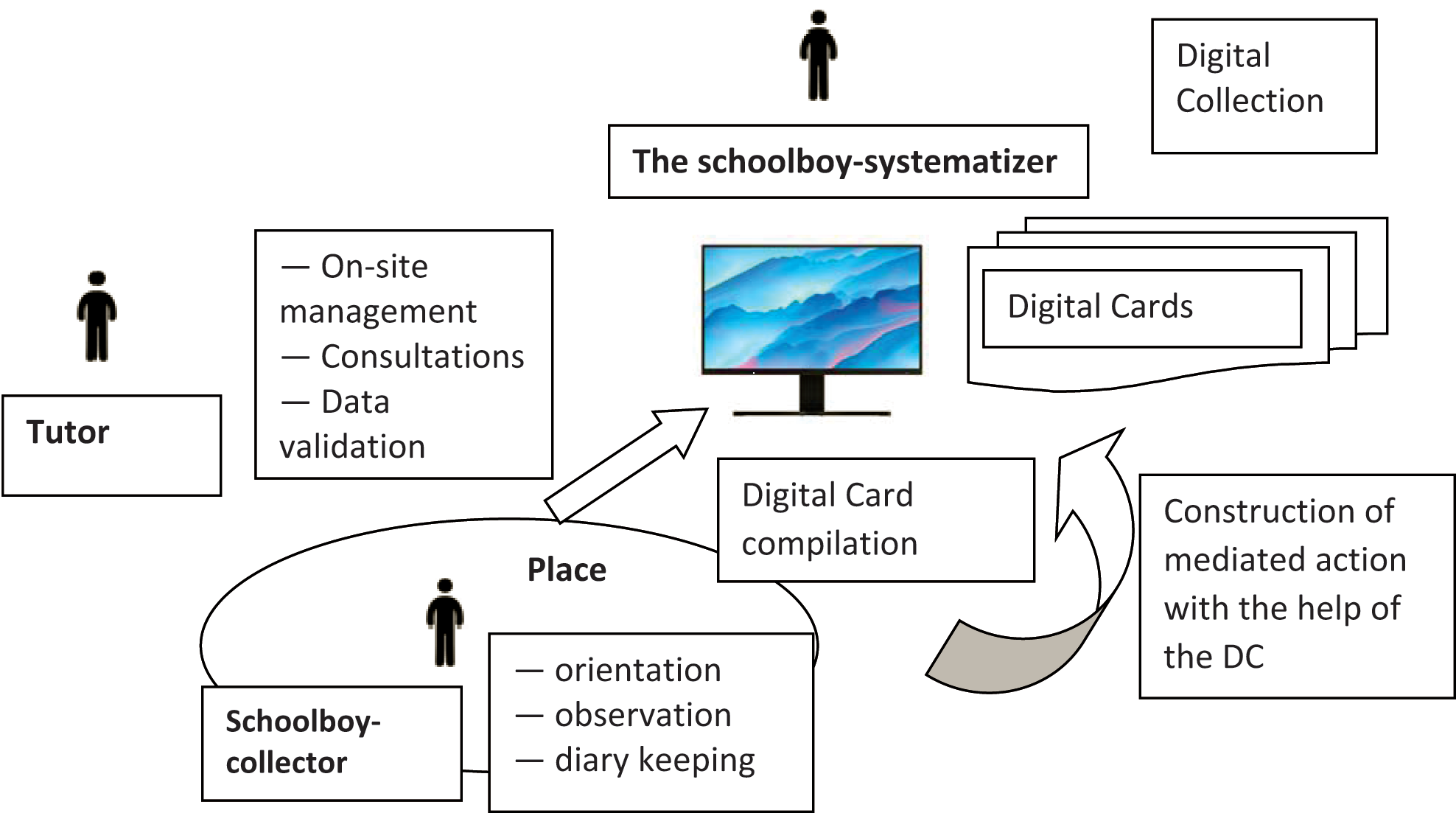

Although this task might look pretty straightforward, it triggers the rules of mediation, similar to the scenario described earlier by B.D. Elkonin in the case of a fairy tale for kids. It is one thing to use pre-designed tools for taking photos of plants; compiling card-catalogues about plants is different, it entails the creation of a new tool by pupils themselves. Gradually filling in datasets related to plants, fungi, and birds a schoolchild develops a more panoramic, extensive vision of biodiversity, shaped, in particular, through the student's own involvement. Thus, we see the diverse role of the schoolchild – not only a collector of materials who knows the area but also an active constructor of a collection, a digital classification system.

Now let's proceed to the crux of the matter. Clearly, the above discussed features of the digital as virtual sign forms, in the absence of effective human guidance, risk dominating the behavior of non-self-standing children. In this case, the challenge is to restore not just the mediating function to the new sign-tool, the digital, but also its capacity to facilitate mastery so that pupils gain control over their behavior and construct their object-oriented actions with the help of an adult, thereby creating a new meaningful field of an exploratory object action. To achieve, this, however, it is necessary to reintroduce an adult into the act of virtual communication.

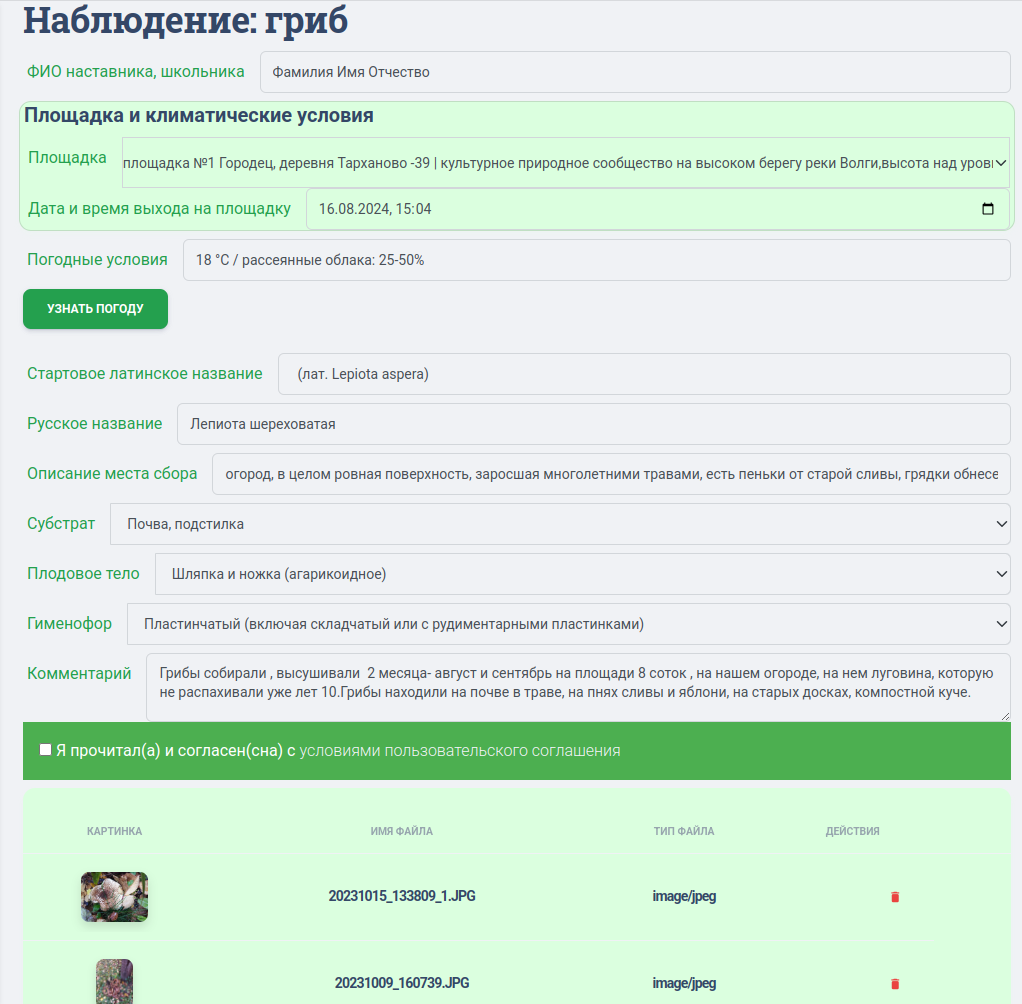

As such an exploratory action, we proposed the task of compiling digital cards that play the role of an intermediary - a digital diary. Pupils filled out digital cards, structured according to predefined data annotations (datasets). A separate digital card was compiled for each natural object (an individual mushroom, plant, bird). The completed cards were uploaded to a database. Data storage enabled immediate use of the digital cards filled in by the schoolchildren for machine learning as labeled datasets. All project work was duplicated by entering information into the Kappa framework. The project stages and tasks are summarized in the Table 1 below.

Table 1

Project stages and types of work for schoolchildren

|

Project stages |

Types of work for schoolchildren |

|

Selection of at least 4 sites for observations: - ability to justify the choice by the objectives of the research; - ability to work with coordinates; - ability to record the site's features. |

1. Creating a place with a point on the map. Orientation on the terrain. 2. Entering a description of the place. Linking to the territory. Designating yourself on the terrain8. |

|

Departure to the place |

3. Receiving GPS coordinates from a smartphone 4. Entering weather data on the date of the visit to the site. |

|

Keeping a field diary of observations: - photo - text description

|

5. Identification, detection of various natural objects in the location (mushroom/plant/bird/other). 6. Recording natural objects using gadgets, identifying them using applications. 7. Creating a record of observation (mushroom/plant/bird/other). 8. Attaching a photo, sound, video. |

|

Expert verification |

10. Validation of records in the database. |

|

Project presentation |

11. Formation of a sample

|

|

Maintaining the database up to date

|

12. Constant access to validated records / Storage of records |

* Note: this refers to the algorithm for describing objects given on the platform of the SSV project9.

Almost all tasks in the right column were performed by schoolchildren together with mentors, except for Item 10, where scientists involved in the project verified the accuracy of the data entered into the digital cards. Consequently, schoolchildren received feedback on their observation diaries, which led to the refinement of the dataset. Subsequently, the students completed a digital card for each natural object (a digital record). An example of a "mushroom" object card is shown in Figure 1 below.

Practically every step-by-step operation of the project followed the logic of expanding the cognitive horizon: site, orientation on the spot – site referencing – identifying and defining an object – snapping and describing an object – mapping an object – inputting and annotating an object in a digital card – compiling the collection of objects in the form of photographs and videos – uploading cards to a database on the platform – accessing the digital collection through the platform – compiling taxonomy and classifying objects – world outlook.

Through this process, schoolchildren developed a new view over nature—not only through their own eyes but equipped with observation data and digital tools.

By filling in the digital cards, schoolchildren acquired a new type of psychological tool that facilitated their research efforts and nurtured elements of investigatory insight. Their perceptual horizons expanded, contributing to the formation of a coherent worldview. The summary is presented in Figure 2.

Discussion

What preliminary conclusions can we draw based on an analysis of the collected materials in line with the specified perspective regarding sign and digital mediation?

1. In the course of reflexive interviews, we found that despite being engaged in basic research practices, schoolchildren struggled to evaluate and articulate their experiences. Most lacked personal reflective assessments of acquiring new modes of action, research action, in the process of studying, in that case, natural materials as part of the SSV project. Schoolchildren faced verbal deficits, struggling to find appropriate words and language to describe even their own feelings, emotions, and impressions, their first elementary experiences of participating in research practices of the project. No one had ever talked to them about it and asked them such kind of questions.

Reflection on their experiences was essentially absent in the SSV project. When we gave pupils reflexive questions regarding their own research experiences, they encountered noticeable difficulties related to self-awareness — what had exactly happened to them? It was hard for them to answer these straightforward questions in their own language; they were unable to say anything to confirm or deny that they had mastered a new mode of action. Assessing their experiences, the schoolchildren relied heavily on adult vocabulary, did not speak for themselves and struggled to find words.

2. Describing their project experiences, schoolchildren predominantly expressed personal feelings and emotional responses, such as: “it was interesting”, “we don’t do it at school”, “it is useful”, “can be used”, “later I will, perhaps, go to the university”, “it broadens horizons”, “learned a lot of new things”, and so on. In this sense, their reflection was predominantly motivational-and-meaningful, surpassing object-and-tool-driven considerations. Few participants were able to demonstrate the latter. For the majority, relationship with adults took precedence, introducing them to a novel form of social interaction. Nevertheless, for some schoolchildren, the operational aspect held greater significance—mastering new procedures, performing lab experiments, studying natural objects, gathering samples10.

In the first part of the article, we postulated that schoolchildren placed in exploratory contexts related to mastering a new object activity should acquire new competencies, perspectives, and a researcher’s mindset—or a "new functional organ", the idea of which we outlined in the first part of the article. Essentially, it implies an ability to discern latent natural processes, the very "third eye."

It turns out, however, that the issue isn't about the digital that is largely irrelevant! The digital doesn't create the new functional organ nor it serves as its mandatory component. Merely incorporating the digital in some form into object activities doesn't guarantee that an individual would develop a new organ. The latter arises from carefully constructed, organized, reflectively framed object-related activity that implies active human engagement—be it a school pupil, a future researcher, or a child immersed in storytelling with the freedom to alter the plot.

The digital (gadgets, tablets, digital maps) may be part of the existing tools or not. You may use as many digital tools as you like, including the most advanced ones, but if the relevant object-related activity of an adult-mediator and a child is not well-planned and built up, if these activities neglect the child's active role as an actor empowered to shape the course of action, no digital platforms or technologies will shape the necessary competencies in children.

Ultimately, our observations and findings corroborate a long-established notion in Cultural-Historical Psychology (CHP). Human abilities develop through try-and-search object-related activities undertaken jointly by adults and children. Simply integrating the digital, using the digital as a sign-tool does not designate and assume the automatic formation of a new organ, a new ability. Such developments rely on specially structured object-related activity involving both adults and children rather than on the digital.

Conclusion

Currently, numerous scholars, including proponents of the concept of Cultural-Historical Psychology (CHP), show an ardent longing to incorporate the digital into the mediation model.

Initially, we also believed that embedding digital devices into schoolchildren's substantive activities would foster the development of a new functional organ, a new capacity enabling them to observe natural objects and see something they did not notice previously. And the digital would facilitate it.

Contrary to the expectations, it turned out that the matter is not in gadgets or digital tools.

Effectively, the CHP concept validated its core principles: human abilities develop with building up a new object-related activity where an adult-mediator plays a pivotal role, while a child assumes an active role as an actor mastering a new mode of action.

The difficulty encountered by schoolchildren in the SSV project due to their inability to reflectively describe their project activity related to material collection and systematization under adult supervision, while using gadgets—highlights the absence of reflective practices as a necessary element of this experience and the fact that the pupils were not engaged in the project as active actors.

These findings imply that the digital alone cannot be an intermediary. It can perform the mediating function in the course of joint actions of an adult mentor and a schoolchild, acting as intelligent assistants interfacing with humans to expedite and optimize the work—but never replacing the human.

1 As highlighted by L.S. Vygotsky, an essential difference between psychological and technical tools lies in the impact focused on the psyche and behavior. A psychological tool changes nothing in an object; instead, it serves as a means of self-influence—on the mind and behavior—not as a means to affect an object directly” (Vygotsky, 1982, p. 106). It should be mentioned that the aspect concerning children's acquisition of self-control remains underappreciated in CHA. Many scholars describe the differences between signs and tools, classify psychological tools, or discuss the mediational function of signs. We believe, however, that the crucial point for Vygotsky begins there and then, where and when a child uses sign-speech to start mastering his/her innate psychic processes and natural behaviors under the guidance of adults (see also Pavlenko, 2020; Polyakov, 2022; Khoziev, 2005).

2 As stated by L.S. Vygotsky: psychological tools are artificial constructs; they are essentially social in nature, not organic or individually adaptive. (Vygotsky, 1982, p. 103)

3 See also: "...mediation is a way of cultivating the Arbitrariness of human activity, i.e., genuine human autonomy and initiative, fostering free action" (Elkonin, 2016, p. 111).

4 Effectively, L.S. Vygotsky equated the process of education with the concept of mastery: "Education is artificial acquisition of natural developmental processes. Education not only influences certain developmental processes but fundamentally reconstructs all behavioral functions" (Vygotsky, 1982, p. 107).

5 This view is shared by many researchers working in the tradition of Cultural-Historical Psychology (CHP). For instance, G. Rückriem argues that Lev Vygotsky's concept emerged back in the era of Gutenberg printing press, predating the digital age. Yet it’s the digital that fundamentally transforms the entire process of mediation. On this basis, Rückriem suggests that the mediation model is not entirely historical since it applies primarily to pre-digital realities and thus cannot adequately explain contemporary digital realities (Rückriem, 2010, p. 32). Rückriem’s conclusions seem self-contradictory. While acknowledging that digital technologies serve as a novel leading tool of mediation in the digital epoch, he simultaneously believes that the basic structure of the activity theory, rooted in the pre-digital, book-centric culture, has become obsolete. Consequently, he calls for substantial revision of the fundamental tenets of the activity theory in light of such new fields of knowledge as multimedia history and theory, etc.

6 According to various research findings, most children gain their initial exposure to the digital in the first three months of life. By the age of two, approximately 90% of children have regular access to gadgets including smartphones and tablets (Cognitive Development..., 2017).

7 See: "Intelligent ways of digitalization open up opportunities for try-search-and-explore modes of orientation. I believe that thinking becomes exposed here" (Elkonin, 2023b). See also our work on the structure of search situations with use of the digital (Smirnov, 2023a).

8 The task is simple but crucial. Some high-school students found themselves in a forest outside the city limits for the first time and were simply scared. Parents had to bring several kids home because of stress, tears, and refusal to continue participating.

10 D.B. Elkonin demonstrated that motivation and meaning precede mastering means and tools. First the meaning, then the tool: "Each period characterized by acquiring operational-and-technical aspects of activity in the world of objects is preceded by a period of internalizing the motivation-and-need component of human activity… The same principle applies to mastering a separate object-related action. Before grasping the operational-and-technical side of an action, a child must first comprehend the significance of such mastering within the system of relationship with an adult" (Elkonin, 1994, p. 100).