Introduction

The technological advancements that have occurred over the past few decades have resulted in substantial alterations to the role that the Internet plays in people's lives. Internet is an integral aspect of our lives, seamlessly integrated into our educational, professional, and recreational pursuits. In April 2023, the number of individuals utilizing the Internet reached 5,18 billion, with this figure demonstrating a consistent upward trajectory. The global prevalence of Internet usage is higher among younger individuals across all regions (Number of internet and social media users worldwide, 2025). The term "Internet use disorders" (IUDs) is used to describe excessive Internet use that is characterised by addictive online behaviour (Montag et al., 2021).

IUDs are common in children, especially in regions with limited public health resources. Consequently, the prevalence of IUD among adolescents in Southeast Asia is 19,6% (Chia et al., 2020), while in Africa it is 30,7% (Endomba et al., 2022). The phenomenon of game playing addiction, which can be considered a type of IUD, has been the subject of growing interest due to its considerable impact on academic performance (Islam, 2020). Additionally, research has demonstrated a link between IUD and self-harm and suicidal behaviour (Marchant et al., 2017). Furthermore, problematic gaming behaviour has been linked to depression, anxiety, obsessive–compulsive disorder and somatization (Männikkö et al., 2020).

The inclusion of gaming addiction in the forthcoming ICD-11 (World Health Organization, 2019) will require an evaluation of its cost-effectiveness in terms of both treatment and management.

The lack of information on the effectiveness of IUD interventions in children, especially those aged 8-12 years old (Lampropoulou et al., 2022), the low effectiveness of treatment in children (Stevens et al., 2019), the unstable effect at follow-up (Kim et al., 2022), and the limited evidence base on treatment effectiveness (Basenach et al., 2023) make the cost-effectiveness of such interventions questionable. The aforementioned facts highlight the need for a differentiated therapeutic approach to school students with different individual risks of IUD persistence, with a particular focus on the priority of intervention and the volume of treatment.

The identification of factors influencing the course of IUDs can provide invaluable insight into the development of effective treatment strategies (Choi et al., 2015). Furthermore, the identification of predictors of IUD remission may enhance our comprehension of the potential pathogenic mechanisms underlying IUD development (Hsieh et al., 2018). A critical review of this literature may assist researchers and practitioners in focusing their attention on the factors that favour IUD remission, particularly those that can be modified and targeted in both intervention and prevention strategies. Furthermore, it would assist in the identification of high-priority groups requiring treatment and the ranking of individuals according to the volume of required interventions.

The predictors of spontaneous remission among school students have yet to be studied. The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to explore which factors favour spontaneous remission in school students with either mobile or non-mobile IUDs.

Methods and materials

Protocol and registration

The present systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA statement (Page et al., 2021).

The systematic review was registered in PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42022296069; registration date: 13/01/2022; registration website: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=296069).

The search strategy, selection, data collection process and data items are available from supplemental data.

Eligibility criteria

In order to be included in the systematic literature review, studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) original research; (2) cohort and case-control longitudinal studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals; (3) the study population consisted of school students of both genders suffering from either mobile or non-mobile IUD (online addictive behavior, including but not limited to gaming and social network use disorders); (4) the type of IUD outcome.

The studies provided evidence of spontaneous remission, defined as the cessation of addiction without any evidence of intervention. Additionally, the studies investigated at least one predictor of remission, including biological, clinical, and psychopathological variables; psychological, social, and demographic characteristics; details on Internet use and beliefs; and characteristics of physical health. Furthermore, the follow-up period in the studies was a minimum of six months.

Studies employing non-human participants and studies in which the population underwent any form of intervention were excluded. Additionally, reviews, case reports, and studies lacking abstracts were excluded.

Information sources

Database searches were conducted using the following databases: PubMed, ProQuest, and the Cochrane Library. The systematic literature search was performed on July 10th, 2025.

In addition, snowballing and manual searches of journals focusing on Internet addiction were used.

Evaluation of risk of bias

Bias was evaluated by two authors using the QUIPS instrument (Hayden et al., 2013).

This tool evaluates nine items: 1) Study Participation, 2) Study Attrition, 3) Outcome Measurement, 4) Study Confounding, 5) Risk of bias on prognostic factors, 6) Statistical Analysis and Reporting. Each item consists of a few issues that can be answered with “yes,” “no,” or “unclear.” Considering the balance of answers to these issues and the subjective importance of each issue, we ranked articles for each type of risk of bias as low, moderate, or high. When there was not enough information, the risk of bias was evaluated as unclear. This step was performed independently by two authors, with any discrepancies discussed until a consensus was reached or resolved through the involvement of a third assessor.

The corresponding author can provide further details regarding the bias estimation algorithm and the evaluation results for each article upon request.

Summary measures and synthesis of results

Qualitative synthesis constituted the primary method of analysis. During the course of the analysis, we provided a summary of the presence and, where possible, the magnitude of the effect of the predictor on the probability of remission. In instances where the original articles presented both multivariate and bivariate analyses, only the results of the bivariate analysis were extracted.

Furthermore, when feasible, a meta-analysis was performed despite its limited statistical power due to the small number of studies. The results of the studies were pooled using RevMan with a random-effects model and a 95% confidence interval. The pooled analyses were contingent on the availability of at least two studies for analysis. The effect measure was the risk ratio for dichotomous data and the standardized mean difference for continuous data. The presence of interstudy heterogeneity was assessed using the I² statistic (Borenstein et al., 2017). An I² value of 25% was considered low, 50% moderate, and 75% high (Higgins et al., 2003). A sensitivity analysis was not conducted due to the small number of studies included in each meta-analysis.

The study enrollment process is presented using a PRISMA-based flowchart (Page et al., 2021). The characteristics of the individual studies included in the review are presented in supplemental data (Table S1). The risk of bias assessment is available from supplemental data (Table S2).

Results

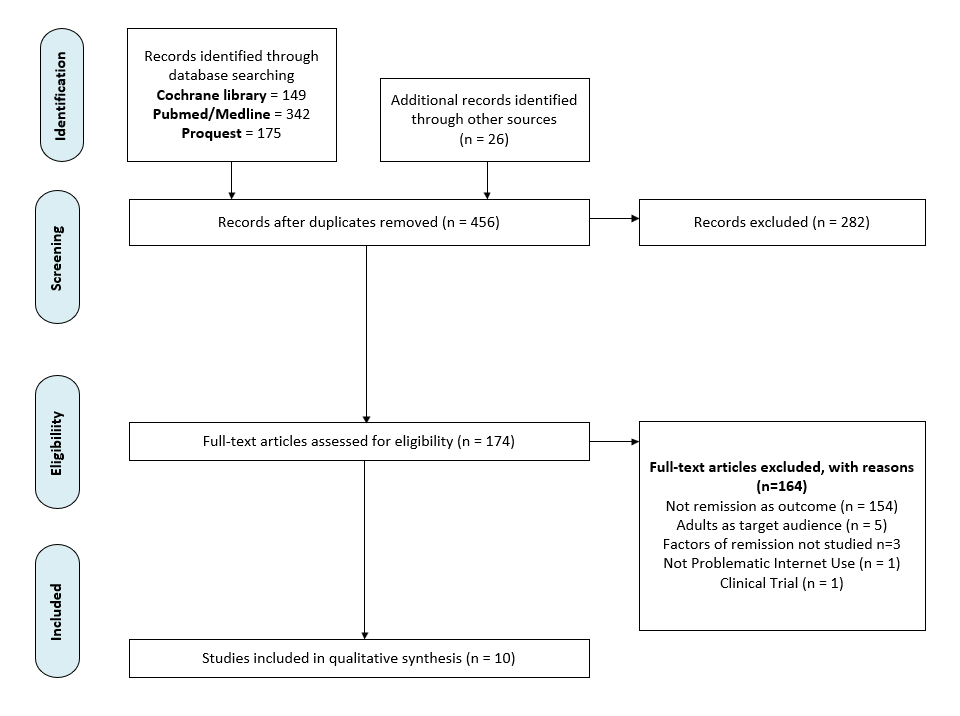

Figure 1 presents a summary of the updated search conducted on the 10th of July 2025 and the inclusion of studies into the review. A total of 666 articles were identified through the database searches. As a result of snowballing and an analysis of the journals, a further 26 studies were included. Following the removal of duplicates, a total of 456 studies remained. Following the evaluation of titles and abstracts, 282 articles were excluded. Of the 174 full-text articles, 164 were excluded on the grounds that they did not meet the pre-established inclusion criteria. These articles were excluded because the outcome of remission was not studied (n=154), because the predictors of remission were not studied (n=3), because in one study the Internet use was not severe, and because in one study the children received the intervention in a systematic manner. In the event of differences of opinion between the two reviewers, these were resolved through consensus and, if necessary, by consulting with a third reviewer.

A total of 10 studies were identified as suitable for this review. All 10 studies were prospective. Since the articles by Ko et al. present the results of one study, we demonstrate duplicate data (on age and sex) only from one of them (Ko et al., 2014; Ko et al., 2015). The majority of studies were conducted in East Asian countries, including Taiwan (n=4), China (n=2), Singapore (n=1), South Korea (n=1), and Japan (n=1). The study by Marrero et al. was conducted in Spain (n=1) (Marrero et al., 2021). The proportion of data available at follow-up was only reported in 2 out of 10 studies and was high: 83,9% (Lau et al., 2017) and 95,4% (Jeong et al., 2021). The studies involved small samples (less than 300 participants), except for the study by Lau et al., which included 1,296 students; the study by Chang et al., which included 605 participants; and the study by Marrero et al., with 550 participants. There is some inconsistency in the age range of the studied population. In most studies, the population of interest consisted of adolescents, except for two studies conducted on younger school students (Gentile et al., 2011; Hirota et al., 2021) and the study by Marrero et al., which involved a mixed population. The proportion of patients who achieved remission at follow-up exhibited considerable variation, ranging from 16,4% to 63,3%. The overall spontaneous remission rate was 44,2%. The follow-up period was either 12 or 24 months, with the exception of the study conducted by Marrero et al., which spanned a shorter period of nine months. Bivariate analysis was employed in seven studies, while multivariate analysis was used in five studies.

Risk of bias in the studies

The characteristics of bias are set forth in supplemental data (Table S2). The potential for bias in the assessment of prognostic factors is illustrated in Table 1, given the considerable number of predictors presented in each article.

In the majority of studies that employed bivariate analysis, the items that constituted study participation bias (including the source of the target population, the instrument used to identify the problem, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria) were adequately described, resulting in a low risk of study participation bias. In the majority of studies, the attrition bias could not be evaluated due to a lack of data regarding the proportion of the population available for analysis at follow-up. The diagnostic methods employed in the majority of articles were found to be highly valid, resulting in a high level of outcome measurement bias. No study protocol involved interviewing or questioning children undergoing psychological or psychiatric interventions during the follow-up period. Consequently, all studies were rated as having a high risk of bias for study confounding. The majority of studies were characterised with a low risk of bias for statistical analysis and reporting. Among all studies, the study by Lau et al. was characterised with a low risk of bias for all types of bias except for study confounding.

Main findings

The influence of various predictors on the probability of remission is illustrated in Table 1.

Social, demographic and lifestyle predictors

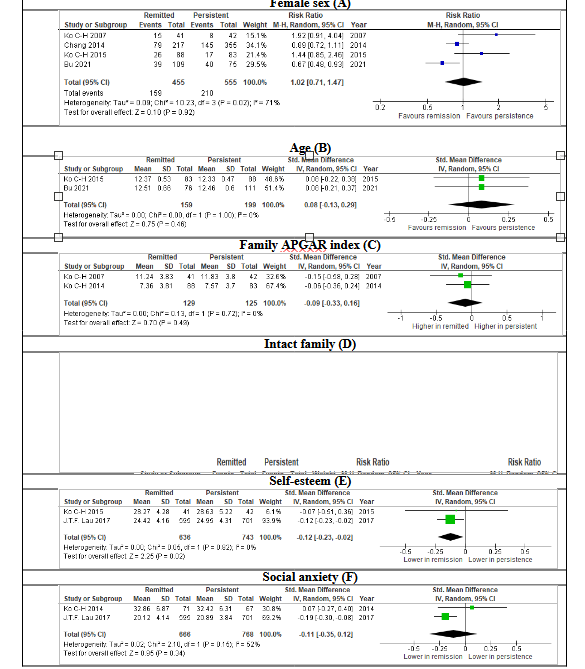

Among studies in which the effect of sex on the probability of remission was evaluated, four (Chang et al., 2014; Hirota et al., 2021; Ko et al., 2007; Ko et al., 2015) demonstrated no association between sex and remission. The article by Lau et al., which was conducted on a large sample and characterized by a low risk of bias, found that sex-adjusted age was not associated with the probability of remission. Conversely, studies by Jeong et al. and Bu et al. demonstrated that female sex favored spontaneous remission. The non-adjusted data extracted from the articles were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 2.A), which demonstrated no association between sex and the probability of remission. It should be noted that the meta-analysis was characterized by high heterogeneity (I² = 67%).

None of the studies in which the effect of age on the probability of remission (Bu et al., 2021; Jeong et al., 2021; Ko et al., 2015) was studied demonstrated a statistically significant difference between the ages of students who remitted and those with persistent IUD. The data extracted from the articles were incorporated into a meta-analysis (Figure 2.B), which revealed no correlation between age and the probability of remission.

The results of the two studies that employed bivariate analysis did not indicate a correlation between school grade and the probability of remission (Ko et al., 2007; Lau et al., 2017). The decision was made not to conduct a meta-analysis due to significant differences in the educational systems of the countries where the studies were conducted. In contrast, Hirota et al. employed a multivariate analysis, which demonstrated a crucial effect of school grade on the probability of remission, with higher grades being associated with a greater likelihood of persistence of IUD.

Many factors related to family relationships were tested for their effect on the probability of spontaneous remission — these include Family APGAR Index (Ko et al., 2007; Ko et al., 2015) and its subscales (Marrero et al., 2021), Family Support Subscale (Lau et al., 2017), whether the child is cared for by parents, presence of adolescent–parental conflict (Ko et al., 2015), Parent-family connectedness (Gentile et al., 2011), attachment to parents, openness of communication with parents (Jeong et al., 2021), marital status of parents, family functioning, and being an only child (Bu et al., 2021). Among these factors, only one was found to have a significant effect on the probability of spontaneous remission in the study conducted by Lau et al. on a large sample: increased family support, which was adjusted for socio-demographic backgrounds. However, the effect size was small (OR=1.03). The data on the effect of the Family Apgar Index on the probability of remission, included in the meta-analysis, demonstrated that there was no effect (Figure 2.C). Furthermore, whether participants had been raised in an intact family did not influence remission probability (Figure 2.D). Other family factors such as not living with father or mother, inter-parental conflict (Ko et al., 2015), and living arrangements with parents (Lau et al., 2017) did not demonstrate any effect on remission.

The status of an internal migrant is not a predictor of spontaneous remission (Bu et al., 2021; Lau et al., 2017).

None of the economic factors, such as household poverty (Chang et al., 2014), socio-economic status (Jeong et al., 2021), or household income (Bu et al., 2021), affected the probability of remission.

In all three studies (Bu et al., 2021; Chang et al., 2014; Lau et al., 2017), neither mother's nor father's education affected remission. A meta-analysis was deemed inappropriate due to the disparate formats employed in describing educational levels across the articles in question. Neither family use of alcohol or smoking (Ko et al., 2015) nor the child's use of alcohol or smoking (Chang et al., 2014) predicted spontaneous remission.

In contrast to Chang et al., Gentile et al. demonstrated the effect of school performance on spontaneous remission: lower school performance predicts spontaneous remission. It should be mentioned that Gentile et al. used a six-point scale to measure school performance, while Chang et al. used a two-point scale, which can explain the discrepancy in data between the two studies.

School bonding (Chang et al., 2014) and school maladjustment (Bu et al., 2021) did not predict spontaneous remission, nor did school type (Marrero et al., 2021).

The probability of spontaneous remission was not found to be affected by social support from family, peers, or teachers (Jeong et al., 2021).

Psychological predictors

The sole factor under investigation was the impact of individual psychological variables on the probability of remission. Ko et al. demonstrated that self-esteem has no effect on the probability of remission. However, Lau et al. showed that higher self-esteem results in remission. Data from two studies included in the meta-analysis demonstrated a small effect size of self-esteem on the probability of remission (Fig. 2.D). It was found that a low level of self-esteem does not affect the probability of remission; however, the cut-off used to measure low self-esteem was deemed inappropriate (Chang et al., 2014).

A related phenomenon—life satisfaction (Ko et al., 2007) and loneliness (Lau et al., 2017)—did not affect the probability of remission.

Such personality traits as novelty seeking, harm avoidance, and reward dependence (Ko et al., 2007) do not affect the probability of remission.

Factors of social adaptation demonstrated no impact on remission according to Gentile et al. and Bu et al., except for isolated goal-setting ability, which favors spontaneous remission. It is noteworthy that the list of social adaptation factors studied in these papers varied.

The capacity for empathy, which has been identified as a factor affecting social adaptation, did not prove to be a reliable predictor of remission.

A lower level of social anxiety was found to favor remission of IUD (OR=0,96) (Lau et al., 2017), but this effect was not demonstrated in the study by Ko et al., conducted on a small sample with questionable risk of bias. The meta-analysis (Fig. 2.E) demonstrated that social anxiety had no effect on the probability of remission.

A lower agreeableness score and a lower conscientiousness score (which represent the self) were found to favor the persistence of IUD (Marrero et al., 2021).

Psychopathological predictors

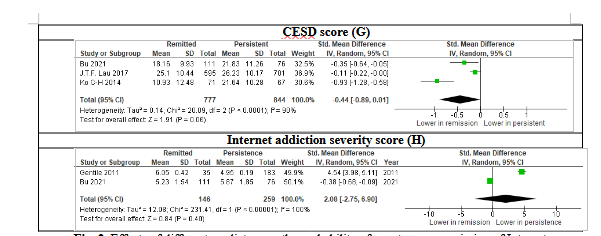

There is currently no consensus among researchers on the effect of depressive symptoms on the probability of remission. Depressive symptoms measured with different scales (CESD score (Lau et al., 2017), Asian adolescent depression scale score (Gentile et al., 2011), CDI (Jeong et al., 2021), HADS (Marrero et al., 2021), and Positive Affect Subscale of the PANAS (Lau et al., 2017)) do not affect the probability of remission. In contrast, Ko et al. and Bu et al. showed that a lower CESD depression score favors remission. The data on depression severity according to the CESD were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 2.F). The effect of depression, as measured by the CESD score, on the probability of remission was not found to reach statistical significance. The probability of remission is not affected by the presence of depression (Chang et al., 2014). However, the absence of severe depression diagnosed using the CESD scale is indicative of remission (OR=0,72) (Lau et al., 2017).

As posited by Gentile et al., anxiety and social phobia scale scores do not influence the probability of remission. Jeong et al. and Marrero et al. support this idea — anxiety scores do not affect the probability of remission.

In contrast to anxiety, conflicting data are observed regarding the role of related phenomena affecting social adaptation: Ko et al. and Marrero et al. found that hostility does not predict remission, but earlier Ko et al. demonstrated that lower interpersonal sensitivity and lower hostility favor remission. The influence of normative beliefs about aggression, hostile attribution bias, aggressive fantasies, and self-reports of aggression on remission has been found to be insignificant (Gentile et al., 2011).

As posited by Gentile et al. (2011), the presence of symptoms associated with ADHD does not influence the likelihood of remission. However, a study conducted by Jeong et al. demonstrated that lower ADHD symptoms are associated with a greater likelihood of remission. It should be noted that the measurement of ADHD severity was characterized by a high risk of bias. Hirota et al.'s findings indicated that among ADHD-RS subscales, a higher score for inattention—but not impulsivity—was associated with a greater likelihood of IUD persistence. It is important to note the use of different types of analysis: bivariate analysis by Gentile et al., and multivariate analysis by Jeong et al. (2021) and Hirota et al. (2021). Additionally, it is essential to consider related phenomena such as impulsiveness (Gentile et al., 2011) and its subtypes (motor, attentional, and non-planning impulsivity) (Marrero et al., 2021), which are measured by BIS; these factors do not affect the probability of remission.

Furthermore, Hirota's et al. findings indicated that a higher autism score is associated with greater persistence, although the effect size was modest (β=0,05).

Finally, a lower baseline CIAS score favored remission (Lau et al., 2017). Similarly, Gentile et al. (2011) demonstrated that a lower problematic gaming symptoms score predicts remission. According to Bu et al., baseline Internet addiction score does not affect the probability of remission. The meta-analysis (Fig. 2.H) revealed no statistically significant correlation between baseline Internet addiction score and the probability of remission.

Internet usage and beliefs

The analysis revealed that several variables pertaining to internet usage did not exhibit a statistically significant correlation with remission (Table 1).

In most studies, the frequency of daily Internet use was not found to be associated with remission (Chang et al., 2014; Gentile et al., 2011; Ko et al., 2007; Lau et al., 2017), except for Jeong et al. (2021), who demonstrated that game time during weekdays less than 60 minutes favors remission, and Marrero et al., who showed that longer time spent playing video games during the week—but not during weekends—favors persistence of IUD.

Neither mode of online gaming (Jeong et al., 2021) nor type of online activity (game playing, chatting, or information search) affects remission (Ko et al., 2007).

In contrast to the objective characteristics of Internet use, the subjective perception of Internet dependence is related to the probability of remission. The following factors have been identified as predictors of remission: the absence of a neutral (OR=1,69) or severe status (OR=2,94) of IA; self-perceived IA status; the absence of perceived susceptibility to IA (OR=1,22); the absence of perceived barriers to reducing Internet use (OR=1.05); and perceived self-efficacy for reducing Internet use. The absence of a cue to action for reducing internet use from parents is another factor that favors remission (OR=1,22) (Lau et al., 2017).

A related phenomenon, namely the regulation of internet use by parents, does not bode well for the possibility of remission (Ko et al., 2015).

Table 1. Predictors of spontaneous remission and persistence of Internet use disorders

|

Authors (year), country |

Prognostic factors studied |

Risk of bias on prognostic factors |

Predictors of spontaneous remission |

|

Social and demographic |

|||

|

Ko et al. (2007) |

sex |

Low |

- |

|

Education level (grade) |

Low |

- |

|

|

Family APGAR Index |

High |

- |

|

|

Lau et al., 2017 |

Sex per 100 person-years |

Low |

- |

|

School grade |

Low |

- |

|

|

Father's education level |

Low |

- |

|

|

Mother`s education level |

Low |

- |

|

|

Living arrangement with parents |

Low |

- |

|

|

Place of Birth |

Low |

- |

|

|

Family Support Subscale of MSPSS-C |

Low |

increased family support (OR =1,03) |

|

|

Ko et al. (2015) |

Age |

Low |

- |

|

Family APGAR Index |

High |

- |

|

|

Sex |

Low |

- |

|

|

Not cared for by parents |

Low |

- |

|

|

Not living with father |

Low |

- |

|

|

Adolescent–parental conflict |

High |

- |

|

|

Not living with mother |

Low |

- |

|

|

Inter-parental conflict |

High |

- |

|

|

Family alcohol use |

Low |

- |

|

|

Family smoking use |

Low |

- |

|

|

Gentile et al. (2011) |

School performance score |

Low |

Lower School performance score |

|

Parent-family connectedness |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Jeong et al. (2020) |

Age |

Low |

- |

|

Sex |

Low |

female sex |

|

|

Non-intact family |

Low |

- |

|

|

SES (socio-economic status) |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Attachment to parents |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Openness of communication with parents |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Social support |

Low |

- |

|

|

Chang et al. (2014) |

Sex |

Low |

- |

|

Father's education |

Low |

- |

|

|

Mother's education |

Low |

- |

|

|

Nonintact family |

Low |

- |

|

|

Household poverty |

Low |

- |

|

|

Academic performance |

Low |

- |

|

|

School bonding |

High |

- |

|

|

Parental attachment |

High |

- |

|

|

Smoking |

High |

- |

|

|

Alcohol use |

High |

- |

|

|

Hirota et al. (2021) |

Sex |

Low |

- |

|

Grade 5 |

Low |

- |

|

|

Grade 6 |

Low |

Higher grade favors persistence β=0,75 |

|

|

Grade 7 |

Low |

Higher grade favors persistence β=0,84 |

|

|

Bu et al. (2021) |

Sex |

Low |

female sex OR =2,1 |

|

Age |

Low |

- |

|

|

Being only child |

Low |

- |

|

|

Internal migrant status |

Low |

- |

|

|

Household income |

Low |

- |

|

|

Marital status of parents |

Low |

- |

|

|

Fathers educational level |

Low |

- |

|

|

Mother educational level |

Low |

- |

|

|

School Maladjustment (Risky Behaviors Questionnaire for Adolescents) |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Family Functioning (Chinese Family Assessment Instrument) |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Marrero et al. (2021) |

sex |

Low |

- |

|

School type (public or private) |

Low |

- |

|

|

Family adaptability (Family APGAR) |

High |

- |

|

|

Family growth (Family APGAR) |

High |

- |

|

|

Family partnership (Family APGAR) |

High |

- |

|

|

Family resolve (Family APGAR) |

High |

- |

|

|

Family affection (Family APGAR) |

High |

- |

|

|

Psychological |

|||

|

Ko et al. (2007) |

Tridimensional personality questionnaire (novelty seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence) |

Low |

- |

|

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale |

Low |

- |

|

|

Brief Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale |

Low |

- |

|

|

Lau et al., 2017 |

Social Anxiety Subscale of the Self-Consciousness Scale |

Unclear |

Lower social anxiety (OR= 0,96) |

|

UCLA Loneliness Scale |

Low |

- |

|

|

Rosenberg Selfesteem Scale |

Low |

Higher self-esteem (OR= 1,03) |

|

|

Ko et al. (2014) |

Social anxiety (FNE) |

Low |

- |

|

Gentile et al. (2011) |

Goal-setting score (Personal Strengths Inventory II) |

High |

Higher Goal-setting score (2,99±0,11 vs 2,70±0,05, p=0,032) |

|

Social competence (Personal Strengths Inventory II) |

High |

- |

|

|

Emotional regulation (Personal Strengths Inventory II) |

High |

- |

|

|

Children’s Empathic Attitudes Questionnaire |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Barratt Impulsiveness Scale |

Low |

- |

|

|

Chang et al. (2014) |

Low self-esteem (Rosenberg≤15) |

high |

- |

|

Bu et al. (2021) |

Factors of social adaptation (Chinese Positive Youth Development Scale) |

low |

- |

|

Marrero et al. (2021) |

Extraversion (Ten Item Personality Inventory) |

Unclear |

- |

|

Agreeableness (Ten Item Personality Inventory) |

Unclear |

higher agreeableness score |

|

|

Conscientiousness (Ten Item Personality Inventory) |

Unclear |

higher conscientiousness score |

|

|

Emotional stability (Ten Item Personality Inventory) |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Openness to experience (Ten Item Personality Inventory) |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Psychopathological |

|||

|

Ko et al. (2007) |

Brief symptoms inventory (BSI) |

High |

BSI: lower Interpersonal sensitivity BSI: lower Hostility |

|

Lau et al., 2017 |

Internet addiction score (CIAS) |

Low |

Lower CIAS score (OR= 0,95) |

|

Depression score (CESD) |

Low |

- |

|

|

severe depression (CESD≥25) |

High |

Absence of severe depression (OR=0,72) |

|

|

Depression score (Positive Affect Subscale of the PANAS) |

Low |

- |

|

|

Ko et al. (2014) |

Depression score (CESD) |

Low |

Lower depression sore |

|

Hostility (BDHIC-SF) |

Low |

- |

|

|

Gentile et al. (2011) |

Normative beliefs about aggression |

Low |

- |

|

Hostile attribution bias |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Aggressive fantasies |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Self-report of aggression |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

ADHD screen |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Depression score (Asian adolescent depression scale) |

Low |

- |

|

|

Anxiety (SCARED) |

Low |

- |

|

|

Social phobia (SPIN) |

Low |

- |

|

|

Problematic gaming symptoms score |

Unclear |

Higher Problematic gaming score (6,05±0,42 vs 4,95±0,19, p=0,020) |

|

|

Jeong et al. (2020) |

Anxiety (Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children) |

Low |

- |

|

Depression (CDI) |

Low |

- |

|

|

ADHD (K-ARS) |

High |

lower ADHD score |

|

|

Chang et al. (2014) |

Severe depression (CESD≥29) |

Low |

- |

|

Hirota et al. (2021) |

Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire total score |

Unclear |

lower autism score |

|

Inattention (ADHD-RS subscale) |

Low |

lower Inattention score |

|

|

Hyperactivity/impulsivity (ADHD-RS subscale) |

Low |

- |

|

|

Bu et al. (2021) |

depression score CESD |

Low |

Lower score |

|

Internet addiction score |

High |

- |

|

|

Marrero et al. (2021) |

Anxiety (HADS) |

Low |

- |

|

Depression (HADS) |

Low |

- |

|

|

Hostility (SCL-90-R) |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Motor impulsivity (BIS) |

Low |

- |

|

|

Attentional impulsivity BIS |

Low |

- |

|

|

Non-planning impulsivity BIS |

Low |

- |

|

|

Internet usage and beliefs |

|||

|

Ko et al. (2007) |

Frequency of Internet use |

High |

- |

|

Time spending on Internet use |

High |

- |

|

|

Type of online activity (game playing or chatting or Information search) |

Low |

- |

|

|

Lau et al., 2017 |

Time spent on Internet use |

High |

- |

|

Self-perceived IA status |

Low |

Absence of neutral (OR=1,69) or severe (OR=2,94) self-perceived IA status |

|

|

Perceived susceptibility to IA |

Low |

perceived susceptibility to IA (OR=1,22), |

|

|

Perceived barrier for reducing Internet use, |

Low |

perceived barrier for reducing Internet use (OR=1,05) |

|

|

Perceived consequences of IA |

Low |

- |

|

|

Perceived benefit of Internet use |

Low |

- |

|

|

Cue to action for reducing Internet use (from parents) |

Low |

cue to action for reducing Internet use from parents (OR=1,22) |

|

|

Perceived self-efficacy for reducing Internet use |

Low |

Perceived self-efficacy for reducing Internet use (OR=1,13). |

|

|

Ko et al. (2015) |

Regulation of Internet use |

High |

- |

|

Allowed to use Internet more than 2 h/day |

Low |

- |

|

|

Gentile et al. (2011) |

General Media Habits Questionnaire (Violent games and amount of gaming) |

High |

- |

|

Frequency of gaming and spending money at gaming |

High |

- |

|

|

Jeong et al. (2020) |

Game time during weekdays (min/day) <60 (vs ≥240) |

Low |

playing <60 min/day (vs ≥240) |

|

Game time during weekdays (min/day): 60-239 (vs. <60), |

Low |

- |

|

|

Most frequently played online game |

Low |

|

|

|

Single-player (vs. None) |

|

- |

|

|

Multiplayer (vs. None) |

|

- |

|

|

Chang et al. (2014) |

Weekly social network website use, days |

Unclear |

- |

|

Weekly online game use, days |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Weekly pornography website use, days |

Unclear |

- |

|

|

Marrero et al. (2021) |

Time spent playing video games during the week |

Low |

Lower frequency |

|

Time spent playing video games on the weekend |

Low |

- |

|

ADHD-RS Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Rating Scale; BDHIC-SF Buss–Durkee Hostility Inventory-Chinese Version-Short Form; BIS Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; CDI Children’s Depression Inventory; CESD Center of Epidemiological Studies – Depression; CIAS Chen Internet Addiction Scale; Family APGAR Index- Adaptability, Partnership, Growth, Affection, and Resolve; FNE Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale; HADS Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IA – Internet addiction; IUD – Internet Use Disorder; IRR Incidence rate ratio; K-ARS Korean version of the ADHD rating scale; MSPSS-C - Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; PANAS - Positive and Negative Affect Schedule; SCARED - The Screen for Child Anxiety-Related Emotional Disorders; SCL-90-R Symptom Checklist-90 Revised; SPIN Social Phobia Inventory.

Discussion

The present systematic review demonstrates that, based on the currently available evidence, a higher level of self-esteem is a predictor of IUD spontaneous remission, although the effect size is relatively modest. In contrast, no significant correlation was found between the probability of spontaneous remission and the following variables: gender, age, intact family, Family APGAR index, father's and mother's education, being an internal migrant, anxiety and social anxiety scores, and impulsiveness.

The significance of certain predictors—including school grade, school performance, hostility and aggression, baseline IUD score, ADHD score and its subscales, and frequency of daily internet use—was found to be inconclusive. A lower depression score does not favor remission; however, the observed tendency must be noted, as there is conflicting data on the role of depression.

The multiple predictors that did not affect the probability of remission may be grouped into three categories: (1) family relations, (2) economic welfare, and (3) macrosocial adjustment.

It is evident that certain demographic and lifestyle predictors—such as family use of alcohol or smoking and the child's use of alcohol or smoking—and psychological predictors—such as life satisfaction and loneliness (factors of social adaptation), ability for goal-setting, empathy, self-awareness, and personality traits (including novelty seeking, harm avoidance, and reward dependence)—have not been sufficiently studied and require further investigation. Similarly, the autism score and beliefs about Internet use warrant further examination.

A systematic review of the effectiveness predictors of IUD therapy has yet to be conducted. It would be beneficial to compare the predictors of spontaneous remission of IUD identified in our review with those associated with remission resulting from intervention.

The impact of additional predictors requires elucidation. Some pivotal intrapersonal risk and protective factors for internet addiction remain uninvestigated—including coping with stress and emotional regulation. The health belief model (Lau et al., 2017), which demonstrated a significant impact on the probability of spontaneous remission in an isolated study, appears to be a promising avenue for further investigation. It is crucial to understand how lower depression rates influence the probability of remission.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the inaugural systematic examination and meta-analysis of the impact of various factors on IUD remission. A further strength of this systematic review is that all included studies were prospective.

Limitations

However, it should be noted that our work is not without limitations. A comparison of the studies is complicated by data heterogeneity, which includes different forms of IUD, different ages, various methods for detecting IUDs, and different ways to measure predictors. Insufficient sample sizes may result in a lack of statistical significance. It should be noted that the conducted studies exhibited at least one type of high-risk bias. The findings from the present review indicate that all studies, with the exception of one, were conducted in Asian countries, and it is unclear whether the results can be extrapolated to other regions. In general, the data from the study by Marrero et al.21 align with the results of other studies.

Despite the limitations of the study, the results may provide valuable clinical insights. Specifically, lower self-esteem has been identified as a predictor of the persistence of Internet addiction, while a lower depression score has been associated with a greater likelihood of remission. It may be advisable to prioritize the treatment of school students exhibiting these phenomena, as they are likely to require a greater volume of interventions. Conversely, positive family dynamics, affluence, and macrosocial integration—along with minimal anxiety and social anxiety scores—and low impulsivity do not increase the likelihood of spontaneous remission of IUD in students. Children and their parents can be informed about the predictors influencing their individual probability of spontaneous remission. Therapeutic programs targeting IUD may be enhanced by focusing on self-esteem. Depressive symptoms may also be targeted, but their nature should be carefully considered.

It is important to note that depressive symptoms can be associated not only with depression but also with social anxiety (Belmans et al., 2019) or perceived online social support (Frison, 2016). Furthermore, the limited effectiveness and safety of antidepressant therapy in children (Gøtzsche, 2022) mean that caution should be exercised when considering antidepressant treatment for children. Additionally, the necessity of targeting family relations, economic welfare, anxiety, social anxiety, and impulsiveness is questionable.

It is essential for future articles to include information on follow-up rates in studies, details on whether participants were undergoing any interventions during follow-up periods, and data on internet use. Researchers should strive to enhance transparency in effect size reporting.

Future research would benefit from larger samples, high-validity diagnostic methods, and studies on homogeneous populations. It is recommended that studies be conducted on diverse populations beyond Asians.