Introduction

The transformation of modern childhood is currently being studied by psychologists, neuroscientists, sociologists, anthropologists, teachers and researchers of children’s subculture. The need to registrate new childhood phenomena and to study the influence of parents and significant adults on the formation of children’s independence in the conditions of modern reality is growing [Roos, 2021]. In the field of developmental psychology [Veraksa, 2018; Tokarskaya, 2019; Sameroff, 2009], research focuses on the search for predictors of the formation of independence, self-control and self-esteem, as well as on the early identification of the risks of problems in a child’s mental development [Barlow, 2018; Finan, 2018; McLeod, 2017; Sanders, 2019; Shaw, 2019]. The focus on early childhood determines the boundaries of the research and tools for assessing the independence level and research activity of the child, the formation of which occurs in the interaction with a significant adult. In this regard, the issue of quality improvement of interaction in the dyad ‘significant adult–child’ at an early age becomes important [Kochanska, 2019]. ‘Interaction in the broadest sense means the process of organising joint activities between the child and the parent. It is a precisely defined behaviour or a set of behavioural habits that can be observed and measured’ [Lisina, 2009, p. 39]. Participation in social interaction requires from a child a certain level of analysis of sensorimotor behaviour in a complex dynamic system, where social partners constantly adapt to each other and influence each other with their actions [Tokarskaya, 2019; Shockley, 2003; Weisberg, 2013]. The quality of an adult’s communicative signals (gestures, physiological manifestations of emotions, verbal accompaniment) when interacting with a child during early childhood determines the development of a certain emotional phenotype of a child, which can persist for a lifetime [Galasyuk, 2019a; Galasyuk, 2017; Karabanova, 2019]. It is noted that the behavioural manifestations of an adult when interacting with a child affect the development of the prefrontal cortex, as well as the formation of a certain type of interaction between emotional and cognitive processes [Boldt, 2020; Madigan, 2019]. According to transactional and bioecological models of development, the child themselves also plays an active and significant role in their own development [Belsky, 1984; Sameroff, 2009; Wachs, 2001]: not only parents influence the development of children but also the characteristics of children influence the behaviour of parents [Collins, 2000; Kochanska, 2004]. Thus, studies of the development of communication between a child and an adult have shown that not only direct care from an adult is important for a child but also a partnership in communication. In this regard, an important direction of research is designing a model of qualitative characteristics of the process of interaction between a young child and a significant adult, the standardisation of behavioural indicators of the child to ‘decipher’ his communicative signals with access to the construction of an ‘independence profile’ [Galasyuk, 2018; Shinina, 2019; Shinina, 2022].

Cross-Cultural Environment of Interaction

In the context of studying the factors affecting the development of the child’s independence, the research of the characteristics of the child’s interaction with a significant adult (parent, educator) in the socio-cultural context of the child’s mental development, including socio-demographic characteristics, are of particular interest [Galasyuk, 2019; Keller, 2018; Mejia, 2017; Savina, 2017].

Comparing the Western and Russian approaches to the communication of a significant adult with a child, it can be noted that Russian culture is characterised by establishing subject-object relations with children at an early age. Subject–subject relations affect the activity of the child and the appeal to their sense of personal responsibility for the consequences of their actions are typical for Western culture [Andreeva, 2019]. At the same time, in the Russian cultural tradition, parents establish a subject-subject relationship with the child later than in the West: in Russia, they talk about the crisis of three years, in the West, they describe the phenomenon of the crisis of two-year age.

For Vietnam, as well as for other countries of the East Asian region, several features that characterise the interaction of parents with children in early childhood can be identified [Lin, 2019]. Vietnam, like Russia, is characterised by a patriarchal family, but the mother plays a fundamental role in the upbringing of the child [Galasyuk, 2019; Jambunathan, 2000; Rindermann, 2013]. During a child’s infancy, the mother, as a rule, provides a fairly liberal (permissive) approach to upbringing: the child is allowed a lot, but as the child is growing up, a more authoritarian style of upbringing compared to the Western countries is being established in the family [Ang, 2006]. Often, mothers use non-physical disciplinary techniques to cultivate a sense of responsibility and duty to the family: psychological manipulations, such as inducing feelings of guilt and shame, are widely used, especially when the child’s behaviour does not meet the expectations of the parent [Galasyuk, 2019; Jambunathan, 2000]. If a child commits a significant misdemeanour, the father is included in the educational process [Jambunathan, 2000].

Approaches to the Study of Child–Parent Interaction

The social situation of early childhood development includes a system of significant relationships of the child with the environment and determines the direction, content and nature of further mental development [Jambunathan, 2000]. Adults plan and direct the child’s actions to master the objective world, culture, values and norms [Polivanova, 2016]. Nowadays there is a growing interest in ‘microanalytical’ studies of what happens in the direct interaction in the child–adult dyad [Dishion, 2017]. This new approach relies on the study of the dynamics of the behaviour of interacting social partners in real time: eye movements, head turns, hand gestures and the nature of the coordination of partner interaction.

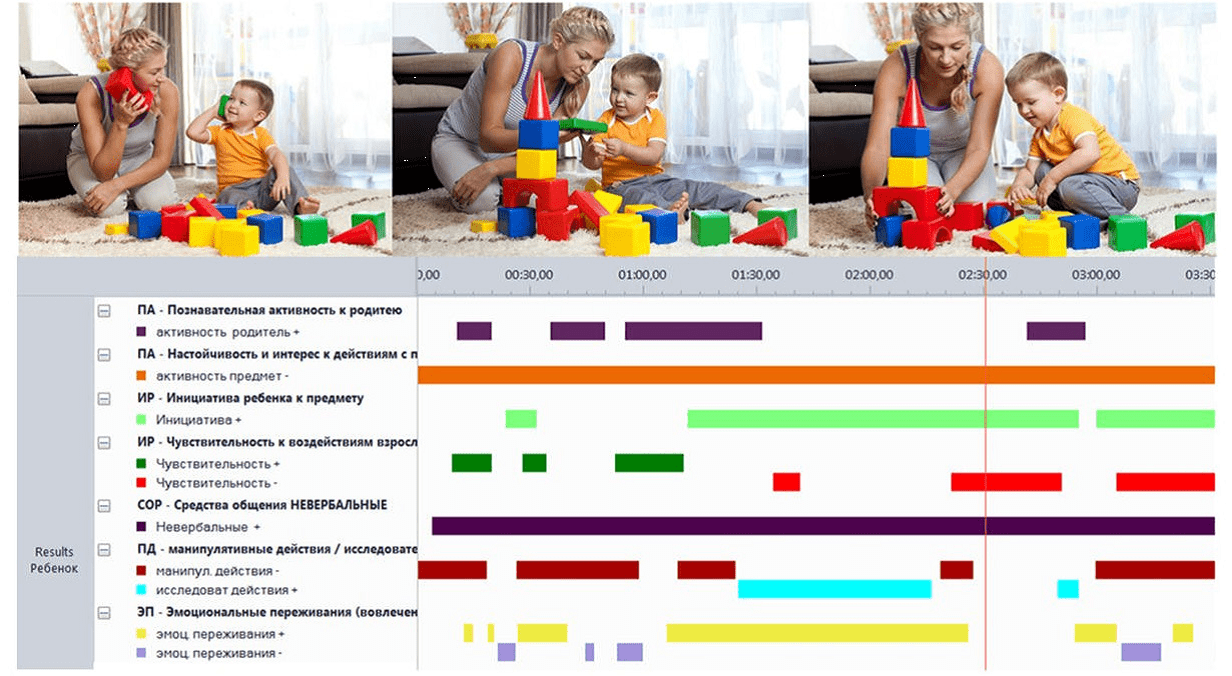

For five years (2016–2022), we have been conducting video studies based on this approach and have been developing a coding system that allows us to record communicative signals in the process of interaction between a child and an adult [Galasyuk, 2018; Galasyuk, 2019a; Galasyuk, 2017; Shinina, 2022]. When coding, initiative acts and responses of the child to the object and the adult are being noted. Figure 1 shows an example of a graphic profile of the child’s communicative signals ‘Research Independence-Sensitivity’ encoded in the computer programme ‘The Observer XT-16.’ Using such a profile, the dynamics of the behaviour of interacting social partners is being recorded.

Figure 1. Graphic profile of the child’s communicative signals ‘Research Independence-Sensitivity’ encoded in the programme ‘The Observer XT-16’

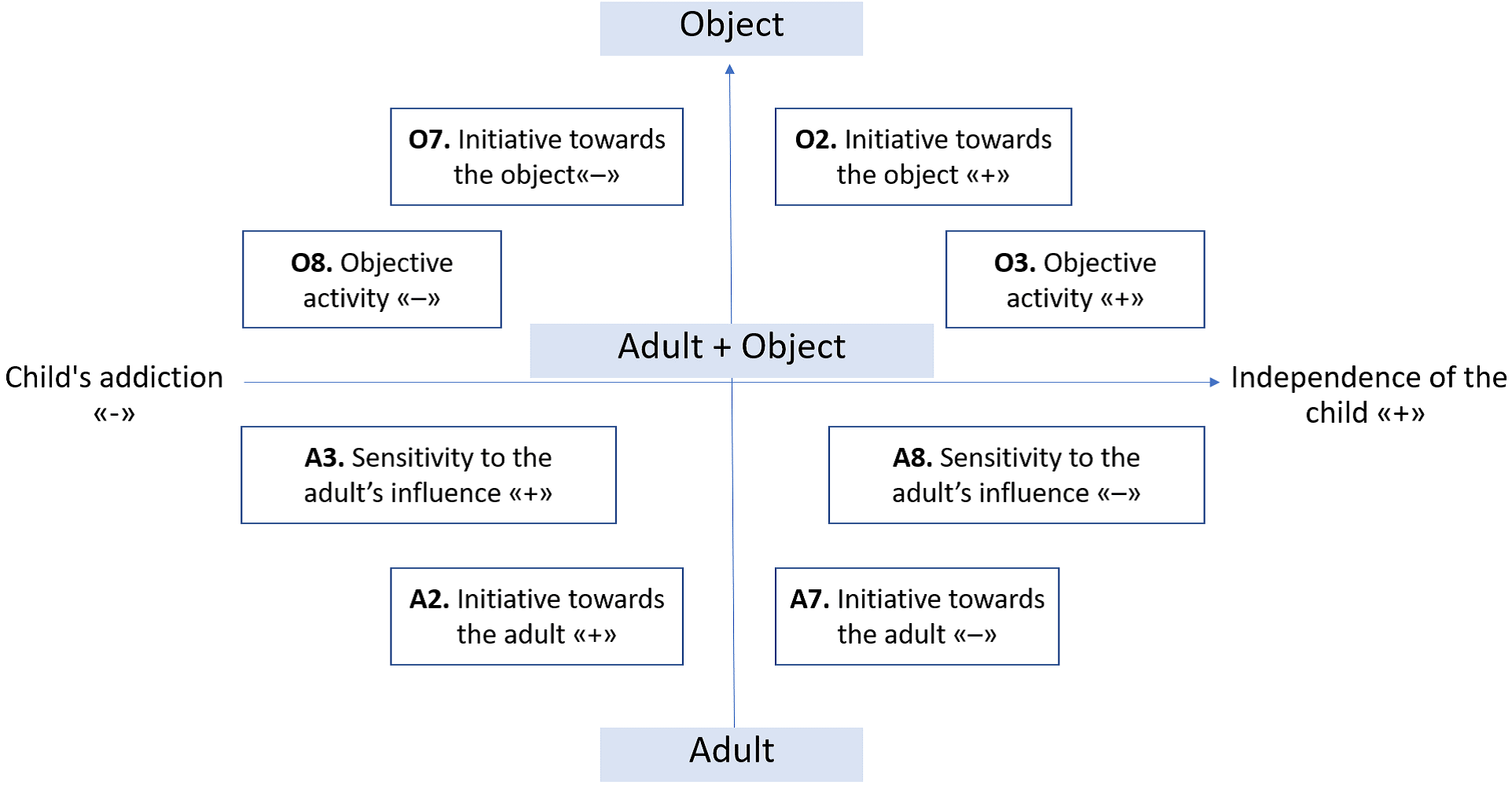

The system of fixing the child’s communicative signals is based on the periodisation of the ontogenesis of communication introduced by M.I. Lisina and her followers [Lisina, 2009; Smirnova, 2020; Smirnova, 2019]. It allows us to consider specific forms of communication between the child and the adult. We rely on two main lines of the behaviour of a toddler, due to age characteristics: communicative and substantive activities. The first is aimed at communicating with an adult and the second—at studying the subject. Each indicator has a positive and negative value. The ‘child–object’ indicator coding system (‘O’) includes ten indicators, of which five are positive: O1. The focus of attention on the object ‘+’; O2. Initiative towards the object ‘+’; O3. Objective activity ‘+’; O4. Communication means (verbal) ‘+’; O5. Emotional experience (non-verbal) ‘+’; and five are negative: O6. The focus of attention on the object ‘–’ object; O7. Initiative towards the object ‘–’; O8. Objective activity ‘–’; O9. Communication means (verbal) ‘–’; O10. Emotional experience (non-verbal) ‘–’. The ‘child–adult’ indicator coding system (‘A’) includes ten indicators, of which five are positive: A1. The focus of attention on the adult ‘+’; A2. Initiative towards the adult ‘+’; A3. Sensitivity to the adult’s influence ‘+’; A4. Communication means ‘+’; A5. Emotional experience ‘+’; and five are negative: A6. The focus of attention on the adult ‘–’; A7. Initiative towards the adult ‘–’; A8. Sensitivity to the adult’s influence ‘-’; A9. Communication means ‘–’; A10. Emotional experience of ‘–’. A detailed description of the coding system, indicators and characteristics is presented in the article by T.V. Shinina and O.V. Mitina [15, pp. 20–21].

As a part of our research, we analysed the real contact between the child and the parent and tried to identify the strategies for the development of the child’s personality, taking into account their needs. In this cross-cultural study, the main focus of our attention was on indicators of communicative signals that allowed us to register the ‘independence–dependence’ of a twenty-four-month child in the process of game interaction with a parent. Based on the objectives of the study, we used a new combination of communicative indicators (eight indicators out of 20) leading to the new fixation model in two dimensions: (1) independent manifestation of signals to the object and (2) interaction with adults. The encoding model is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Encoding model of communicative signals of the child ‘Research independence-sensitivity’

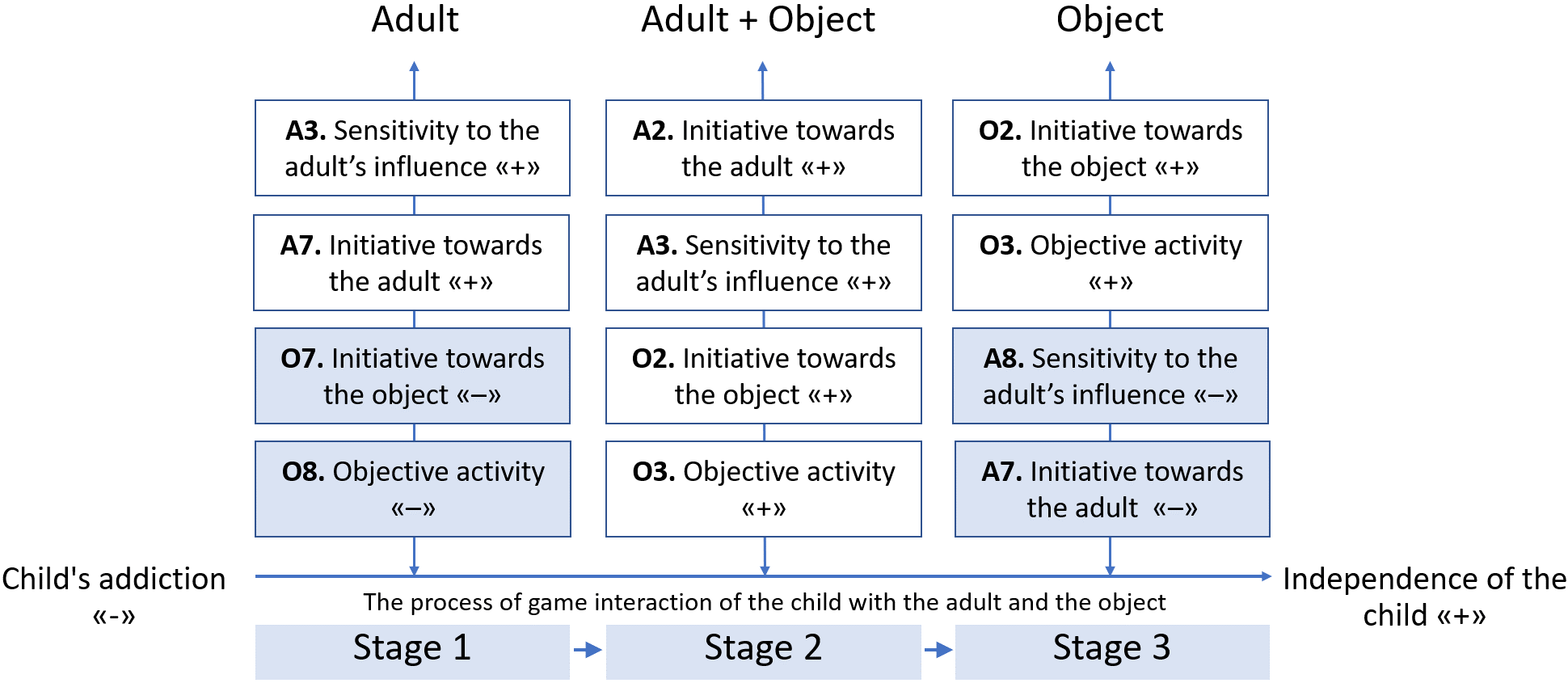

In our opinion, the scale of dynamics of development of a child’s independence in the process of interaction with the object and the adult, presented in Figure 3, includes three stages: Stage 1. ‘Child dependence’ (indicators: O7; O8; A3; A7); Stage 2. ‘Child’s independence development through an adult and an object’ (indicators: A2; A3; O2; O3); Stage 3. ‘Independence of the child’ (indicators: O2; O3; A8; A7). In Stage 1. ‘Child’s dependence’, the child shows an object position: they do not show research interest in the object, manipulate with different objects, wait for initiative and support from an adult and show increased sensitivity to any proposals of an adult. In Stage 2. ‘Child’s independence development through an adult and an object’, the child begins to actively explore the object, shows initiative to the adult, involves them in joint activities and demonstrates sensitivity to what the adult introduces to the child in the process of game interaction. In Stage 3. ‘Independence of the child’, the child has their own point of view. They understand exactly what they want, take the initiative while interacting with an object, explore it and actively interact with it. At the same time, in the case of adult interference in the game activity, the child defends their boundaries.

Figure 3. Scale of dynamics of child’s independence development in the process of interaction with the subject and the adult

Research Programme, Sample Characteristics and Applied Methods

As a part of the longitudinal study of the interaction of parents and children from Russia and Vietnam, the relationship between the child’s behaviour in the process of game interaction with a significant adult (in this case, with the mother) and the level of social and emotional development of toddlers has been studied. The article presents the main results of a part of the research on the dynamics of a child’s independence development in the process of interaction with the subject and in communication with an adult at the age of two years. The research aims to determine the stage of a child’s independence development by the age of twenty-four months, in the process of interaction with the subject and in communication with an adult and to determine the level of social, emotional and adaptive development of children in Russia and Vietnam.

The study involved 43 dyads (mother + child): 22 dyads from Russia and 21 dyads from Vietnam, Nha Trang. In total, the study involved 43 typically developing babies aged 22 to 26 months (mean value M = 23.35, standard deviation SD = 1.35), of which 19 boys (44.2%) and 24 girls (54.8%).

The project involved families who met the following criteria: (1) a complete family with biological parents, (2) the absence of malformations of the brain, heart and other internal organs, (3) the absence of prematurity, perinatal and postnatal injuries, (4) the Russian-speaking environment in which the child develops in Russia and (5) the Vietnamese environment in which the child develops in Vietnam.

In the study, we used the following techniques:

1) Method for studying the social and emotional development of the child—Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (BSID-III). The study procedure included a survey of a significant adult on all blocks of the methodology with the introduction of data into the answer form.

2) Method of assessing child–parent interaction—‘Communicative signals of the child’ scale in Evaluation of Child–Parent Interaction (ECPI-2 ed.), including a combination of indicators that allow recording the independent research activity of the child in relation to the subject and a significant adult in the process of spontaneous play [Galasyuk, 2019; Shinina, 2022; Shockley, 2003].

Studies were conducted in a multifunctional environment: significant objects of the child with which they like to interact in their free time and towards which they could show an active position, have been chosen by the parents. We did not standardise the set of items and took into account the individual characteristics and preferences of the child. The study procedure included instructions for the parent: ‘Play with the child the way you play at home.’ Fifteen minutes of child–parent interaction were recorded. Then the video case was analysed, and the micro-actions of the child were noted. Next, the child’s signals were encoded using the computer programme ‘Observer XT-16.’ The analysis of the video recordings was carried out by two behavioural analysts who underwent special training and achieved, with an independent analysis of the same records, the coefficients of consistency of expert assessments of indicators for a child of an 87% level of coincidence of results [Galasyuk, 2018].

Statistical processing of the data obtained was carried out in the programme IBM SPSS Statistics 26.0. The following methods of mathematical processing of empirical data were used: correlation and factor analysis, determination of the statistical significance of the differences in paired measurements based on the U-criterion of Mann–Whitney.

Outcomes

To identify the differences in communicative signals manifested by children in the process of interaction with an adult in Russia and Vietnam, the values of the Mann–Whitney U-criterion were calculated (Table 1).

Table 1

Descriptive statistics and values of the Mann–Whitney U test on the child’s communicative signals for two independent samples (N = 43)

|

Research variables |

Descriptive statistics* |

Values of the Mann–Whitney U test |

p-level importance |

|||

|

Russia (N = 22) |

Vietnam (N = 21) |

|||||

|

M (SD) (s) |

Me (s) |

M (SD) (s) |

Me |

|||

|

O2. Initiative towards the object ‘+’ |

252 (133) |

247.5 |

328 (134) |

328 |

58.5 |

0.30 |

|

O7. Initiative towards the object ‘–’ |

43 (36) |

36 |

29 (82) |

4 |

21.5 |

0.07 |

|

418 (90) |

471.5 |

442 (117) |

462 |

53 |

0.57 |

|

|

O8. Objective activity ‘–’ |

60 (48) |

42 |

6 (10) |

0 |

4 |

0.001 |

|

A2. Initiative towards the adult ‘+’ |

41 (40) |

34 |

54 (26) |

45 |

57.5 |

0.34 |

|

A3. Sensitivity to the adult’s influence ‘+’ |

258 (87) |

254 |

61 (33) |

58 |

1 |

0.001 |

|

A8. Sensitivity to the adult’s influence ‘–’ |

80 (53) |

65 |

14 (19) |

7 |

7 |

0.002 |

Symbol: *—duration of manifestation of the indicator for 15 minutes, averaged by dyads.

Statistically significant differences depending on the country of residence were identified by the following communicative indicators of the child: O8. Objective activity ‘–’ (U = 4, p < 0.001), A3. Sensitivity to the adult’s influence ‘+’ (U = 1, p < 0.001) and A8. Sensitivity to the adult’s influence ‘–’ (U = 7, p < 0.002). The manifestations of Indicator A3. Sensitivity to the adult’s influence ‘+’ in the Russian sample lasted longer (M = 258; SD = 61) than in the Vietnamese one (M = 61; SD = 33). The manifestations of Indicator A8. Sensitivity to the adult’s influence ‘–’ in the Russian sample lasted longer (M = 80; SD = 53) than in the Vietnamese one (M = 14; SD = 19). The data obtained allowed us to talk about the dominance and strengthening of the behavioural pattern of sensitivity over the initiative in the process of child–parent interaction. It was important for the child to be responsive to the parent’s signals and meet his expectations, which was especially evident in the sample from Russia.

To identify differences in the level of socio-emotional development and the formation of skills necessary in ordinary everyday life, the values of the U-criterion of Mann–Whitney were calculated between samples from Russia and Vietnam (Table 2).

Table 2

Descriptive statistics and values of the Mann–Whitney U test on the BSID-III scales for two independent samples (N = 43)

|

Scale BSID-III |

Descriptive statistics |

Values of the Mann–Whitney U test |

p-level importance |

|||

|

Russia (N = 22) |

Vietnam (N = 21) |

|||||

|

M (SD) |

Me |

M (SD) |

Me |

|||

|

Socio-emotional |

107.6 (7.9) |

108 |

105.1 (13.7) |

109 |

213.5 |

0.67 |

|

Communication |

46.0 (11.9) |

41.5 |

44.95 (13.51) |

44 |

219 |

0.77 |

|

Living in the community |

22.8 (9.3) |

22 |

26.2 (16.4) |

28 |

250.5 |

0.64 |

|

Functions of the pre-school period |

18.1 (10.4) |

14 |

12.2 (8.3) |

10 |

140.5 |

0.03 |

|

Life at home |

45.5 (10.1) |

44.5 |

41.9 (15.7) |

46 |

213.5 |

0.67 |

|

Health & Safety |

40.5 (8.5) |

40 |

36.1 (12.6) |

35 |

186 |

0.27 |

|

Leisure |

44.7 (7.9) |

43.5 |

44.1 (8.8) |

44 |

229 |

0.96 |

|

Self-care |

50.8 (7.6) |

50 |

44.0 (9.4) |

45 |

125 |

0.01 |

|

Self-regulation |

47.1 (8.0) |

47.5 |

45.2 (13.2) |

44 |

215 |

0.69 |

|

Social environment |

44.3 (8.7) |

41.5 |

41.5 (10.6) |

40 |

189.5 |

0.31 |

|

Motor skills |

62.7 (4.1) |

63.5 |

63.2 (7.9) |

62 |

228.5 |

0.95 |

Statistically significant differences depending on the country of residence are identified on the following scales: ‘Functions of the pre-school period’ (U = 140.5, p < 0.03) and ‘Self-care’ (U = 125, p < 0.01).

Discussion of the Results

The fundamental role of the interaction of a child of early age with a significant adult acquires today a new meaning from the point of view of the formation of research activity and independence of the child. Despite the high and constant interest in the topic of early development, child–parent interaction at the initial stage of ontogenesis has not been studied fully enough; it is often presented descriptively, through the enumeration of development standards. This study presents the way of identification of significant behavioural indicators of children’s independence and stages of the child’s independence development in the process of interaction with an object and in communication with an adult, as well as determination of the levels of social, emotional and adaptive development of young children from Russia and Vietnam.

The obtained results show that children from the Russian sample are in the process of transition between the second and third stages of the scale of the child’s independence development in the process of interaction with the object and the adult. Children from Russia show initiative to the object, explore the object, show initiative to the adult, involving them in joint activities and demonstrating sensitivity to what the adult introduces in the process of game interaction, which is typical for the second stage. At the same time, the Sensitivity to the adult ‘–’ indicator in the Russian sample manifests itself much longer than in the Vietnamese one, and that allows registration of the transition to the third stage. In their turn, the children from Vietnam demonstrate a more pronounced repertoire of indicators related to the second stage of the scale of formation of a child’s independence in the process of interaction with the subject and the adult: O2. Initiative to the subject ‘+’; O3. Subject activity ‘+’; A2. Initiative to the adult ‘+’; A3. Sensitivity to the effects of an adult ‘+’.

Manifestations of indicator A7. The initiative to the adult ‘–’ has not been registered in any of the samples. This indicator is characterised by the exclusion of the parent from the game and the manifestation of autonomy in the process of interaction with the object. Such a result may indicate an unformed need to play independently, due to age or increased activity and directiveness of the parent in the process of interaction. Previously, we have found that Russian mothers use didactic and spontaneous play strategies independently of each other, and Vietnamese mothers are more likely to use both strategies simultaneously. Indicators of the frequency of using educational toys in relation to traditional ones in the Russian sample are higher than in the Vietnamese one. No significant differences have been revealed in the sets of presented toys [Galasyuk, 2019].

It should be mentioned separately that a high level of sensitivity to an adult ‘+’ involves switching the child’s attention from an object to an adult and reducing, up to the cessation, of the child’s objective (research) activity. The objective activity ‘–’ characterises the moments when the parent interrupts the child’s initiative act and offers another type of activity; this difference is observed in the Russian sample, and it is possible to registrate low values for this indicator in the Vietnamese sample. That has been confirmed by the statistical data.

The results on the Bailey scales (BSID-III) confirm the results obtained by the ECPI, i.e. the level of independence in children from the Russian sample is generally higher than in children from the Vietnamese sample. Statistically significant differences in the following scales have been revealed: ‘Functions of the pre-school period’ and ‘Self-care’, which reflect the development of skills and allow us to talk about the formation of the operational and technical block of independence. In general, according to the Bailey scales (BSID-III), in both samples, there is a fairly high (above average) level of formation of socio-emotional skills and behaviours in ten skill areas.

It should be noted that according to our previous research, the toys and games of Vietnamese children are associated with orientation to everyday life and are aimed at the formation of social and household skills. This is confirmed by the data obtained on the Bailey’s ‘Life in the Community’ scale (BSID-III): the indicators of the Vietnamese sample are generally higher than those of the Russian one. Toys and games of Russian children are mainly developmental in nature, which is confirmed by high scores on the Bailey’s ‘Functions of the pre-school period’ scale (BSID-III).

Main Results of the Study

- Children from the Russian sample are in the process of transition between the second and third stages of the scale of a child’s independence development in the process of interaction with an object and the adult. It should be noted that the duration of the manifestation of the indicators A3. Sensitivity to the effects of adult ‘+’ and A8. Sensitivity to the effects of the adult ‘–’ significantly prevails in the Russian sample.

- Children from the Vietnamese sample show a more pronounced repertoire of indicators related to the second stage of the scale of a child’s independence development in the process of interaction with the subject and the adult.

- No manifestations of indicator A7. The initiative to the adult ‘–’ have been registered. It indicates that such a need has not been formed yet and none of the respondents has reached the third stage of the scale of a child’s independence development in the process of interaction with the object and the adult. We can explain this fact by the early age of the participants (from 22 to 26 months) and suggest that it emerges later. So, we hope to find it at the next stage of the longitudinal study (at the age of 36 months).

- The level of independence in children from the Russian sample is generally higher than in children from the Vietnamese sample. Statistically significant differences in the following scales have been revealed: ‘Functions of the pre-school period’ and ‘Self-care’ according to the Bailey scales (BSID-III), which allows us to talk about the formation of the operational and technical block of independence. The data obtained may be explained, among other things, to differences in the children’s play arsenal. Toys and games of the Vietnamese children are associated with orientation to everyday life and are aimed at the formation of social and household skills, which could affect the indicators on the scale ‘Life in the community’, whereas toys and games of the Russian children are mainly developmental in nature, which could give high scores on the scale ‘Functions of the pre-school period’ of Bailey (BSID-III).

- To study the dynamics of development of the child’s independence in the process of interaction with the subject and the adult at the third stage of the longitudinal study (at 36 months) further work is required. It will help us to detail the main neoplasms of the ontogenesis of the child’s personal development in the process of interaction with a significant adult, identify the dominant types of behaviour of young children and to study the influence of a significant adult on the development of cognitive activity and independence of children.