Introduction

“Do you strive to fully realize your knowledge, talents and abilities in socially significant events / professional activities / relationships with others?” A person who answers positively to this and similar questions confirms, first of all, to him/herself the sense of satisfaction with own actions their results in various life circumstances — such person is content/gratified with how successful the realization of creative, professional, communicative, intellectual, motivational etc.potentials is.In other words, a person positively evaluates what professional psychologists describe by the term “self-realization” or “self-efficacy” [Bandura, 1986].The former term characterizes a person’s self-assessment of how fully her/ his personal potential is realized, while the second literally describes a person’s perception of own ability to carry out certain activities at the expected/given level of success and is very often considered in the context of educational activities [Schunk, 2016].Both psychological phenomena combine pronounced motivational (“what I aspire to”) and cognitive-evaluative (“how successfully I manage realization of these aspirations”) components.

Obviously, self-realization affects various spheres of human life.S.I.Kudinov identifies three basic areas of self-realization — personal, professional and social [Kudinov, 2017].In the structure of self-realization of an individual person, a certain area may prevail, while others recede into the background.This is a natural process that reflects the vital interests and priorities of the individual.

However, a disproportionately low level of self-realization in one area potentially threatens the overall psychological adaptation — a serious dissatisfaction with the degree of fulfilling one’s potential even in limited certain aspects of life is frustrating, gradually spreading to other areas, reducing motivation for them, causing a feeling of tension and discomfort — and, as such, need adequate psychological correction.

Study Problem and Rationale

The Fundamentals of the Youth Policy of the Russian Federation for the period up to 2025, name as the main goal educating “patriotic youth with independent thinking and a creative worldview, with professional knowledge, capable of demonstrating high cultural standards, responsibility and the ability to make independent decisions” [Rasporyazhenie Pravitel'stva Rossijskoj], i.e., creating conditions for meaningful self-realization.According to the document, youth policy should be focused on the comprehensive promotion of self-realization of young people through their involvement in the volunteer movement, various social and educational projects, grant competitions, professional start-ups, etc.However, despite the numerous opportunities for self-realization, the social activity of young people remains rather low, as evident from various empirical studies [Azarova, 2008; Obukhova, 2021].

Among the three previously named types, social self-realization is especially interesting in its relation to other psychological characteristics.It has been established that individuals with a high level of social self-realization are characterized by a high level of social (dynamic in interpersonal communication) and emotional (high level of empathy and tolerance) types of intelligence, as well as a more harmonious self-concept that combines a high level of self-control, the desire for self-fulfillment, a high rate of self-actualization and meaningfulness of life.It has also shown that volunteering in the perception of young people is no longer limited to being driven by altruistic motives [Azarova, 2008], but also includes compensatory and pragmatic motives: benefits, personal growth and expansion of social contacts [Azarova, 2008; Palkin, 2019; Rashodchikova, 2019].

Empirical evidence also points to emotional intelligence as a significant predictor of successful self-realization.People with a high General Factor of Personality, which is also a recognized indicator of overall social performance, typically show higher results on emotional intelligence scales [van der Linden, 2017].

A meta-analysis of the connection of emotional intelligence to learning shows that students with a higher level of the former emotional are better able to cope with negative emotions associated with academic performance (anxiety, boredom, frustration) — supposedly, due to the ability to better control own emotions and influence the emotional reactions of others.They also demonstrate a high potential for successful interaction with others and more successfully build relationships with teachers, peers and the family [MacCann, 2020].Developed emotional intelligence reduces indecision when building individual professional trajectories [Saka, 2008], enhances the experience of positive emotions and suppresses / compensates for negative ones, thus, contributing to the development of more flexible mental models (characterized by high creative potential), and subsequently to more effective professional self-realization [Tugade, 2001].

Ability to develop behavioral responses and thought processes (including manifestations of emotional intelligence) that are instrumental in achieving well-being, also underlies higher levels of personality development — quite in accordance with A.Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.Indeed, at a higher level of self-realization, a person tends to experience less anxiety, more effectively solve emerging problems and more fully enjoy the opportunities that open up.All this puts emotional intelligence within the array of factors that contribute to successful self-realization of the individual [Maslou, 2016].

Personal characteristics are also factors capable of influencing self-efficacy [Stajkovic, 2018].For example, consciousness, extraversion and neuroticism often significantly correlate (the latter — negatively) with self-efficacy [Marcionetti, 2016; Brown, 2011].

To summarize, it is worth noting we that the attention of research on self-realization is largely drawn to the problems of its age-driven dynamics and differences in the saliency of its types — personal, social and professional.Of some special interest are particularly low indicators of social self-realization in young adults — when there is even the need for employing methods of psychological compensation / correction [Kostakova, 2013; Shamionov, 2019].

Considering the above data on the high compensatory potential of emotional intelligence, including our own earlier study [Obukhova, 2021] and the importance of taking into account personal characteristics when analyzing the adaptive capabilities of young adults, the following questions and the related research hypotheses were formulated:

- What level of social self-realization (including in comparison with its other types) and indicators of emotional intelligence do characterize the sample of young adult participating in the study? Accordingly, the H1 hypothesis suggests that respondents’ self-assessment of the level of social self-realization is lower than personal and professional ones, with a significant variation in emotional intelligence indicators.

- Do the level of social self-realization and indicators of emotional intelligence differ between respondents in the groups of working (combining studies at a university with work and, accordingly, having longer professional experiences) and studying (full-time students who are not included in any labor activities) participants? Hypothesis H2 suggests significant differences in the level of expression of self-realization, but not in the indicators of emotional intelligence, as potential predictors of self-realization, between the groups of working and studying participants.

- What factors influence the degree of manifestation of social self-realization in the sample as a whole and in working and studying groups? Accordingly, the H3 hypothesis tests the relationship of professional experience, personal characteristics (especially, extraversion), and indicators of emotional intelligence, first of all, the ability to understand emotions (as a potentially important compensatory / adaptive factor) with the subjective perception by young adults of their social self-realization.

Study Sample and Instruments Used

The study sample consists of 125 students of the Southern Federal University (107 girls and 18 boys) aged 18-38 years (mean age 22.15, SD=4.70).At the time of the study, 74 were full-time students, while the remaining 51 — combined study with work in their respective professional fields.Accordingly, we distinguished between the groups of studying and working participants.The groups did not differ in terms of gender composition: 64 and 41 women and 10 and 10 men, respectively (the chi-square value of 0.83 was not statistically significant, p = .36).The indicator of professional experience included the number of full years of both work and training in the respective professional speciality.

To assess the three types of self-realization of the respondents, the study used the Multidimensional Self-Realization Questionnaire by S.I.Kudinov [Kudinov, 2017].This instrument contains 101 questions with 6 options for answers: from “no” to “definitely yes”).The values of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for the test scales range from 0.72 to 0.78, with the test-retest reliability coefficient of 0.76 (p < .01).

Various components of emotional intelligence were assessed with the EmIn questionnaire by D.V.Lyusin [Lyusin, 2004].The test contains 46 statements evaluated on a 4-point Likert-wise scale).Cronbach’s alpha values for the test subscales range from 0.75 to 0.79.

“Big Five Inventory-2” (in the Russian adaptation of S.A.Shchebetenko [Kalugin, 2021]: 61 questions) assessed respondents’ major personal factors (Big Five).The test has Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 — for raw scores and 0.85 — for centered scores, thus, indicating high internal consistency.The checklist of basic socio-demographic data included questions regarding gender, age, field of study and professional specialization, as well as of structural subdivision within the university, and the length of study / work.

Participation in the study was voluntary and no remuneration was paid to participants.Participants filled out the response forms of all measures individually.The respondents’ anonymity was ensured.The collected data were processed in the SPSS 26.0 package by means of the following statistical procedures.An unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare the groups of respondents on major variables, Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the direction and degree of relationships among variables, and multiple regression analysis was used to assess the relative contribution of various predictors to the distribution of the criterion variable of social self-realization.

Results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics for all variables and cross-correlations among them for the sample as a whole are summarized in Table 1.

First, we were interested in whether there are differences in the major variables between the working and studying groups, regardless of the age factor.There is a statistically significant relationship between age and professional experience (r = 0.459, p < .01), while professional experience (naturally higher for the working participants), but not age, is significantly positively correlated with several major variables, except for personality traits (their relatively stable nature throughout their life cycle is quite well documented).It should be noted that as the experience of professional activity is gradually acquired with time, the indicators of all types of self-realization decrease.

3.What factors influence the degree of manifestation of social self-realization in the sample as a whole and in working and studying groups? Accordingly, the H3 hypothesis tests the relationship of professional experience, personal characteristics (especially, extraversion), and indicators of emotional intelligence, first of all, the ability to understand emotions (as a potentially important compensatory / adaptive factor) with the subjective perception by young adults of their social self-realization.

Study Sample and Instruments Used

The study sample consists of 125 students of the Southern Federal University (107 girls and 18 boys) aged 18-38 years (mean age 22.15, SD=4.70).At the time of the study, 74 were full-time students, while the remaining 51 — combined study with work in their respective professional fields.Accordingly, we distinguished between the groups of studying and working participants.The groups did not differ in terms of gender composition: 64 and 41 women and 10 and 10 men, respectively (the chi-square value of 0.83 was not statistically significant, p = .36).The indicator of professional experience included the number of full years of both work and training in the respective professional speciality.

To assess the three types of self-realization of the respondents, the study used the Multidimensional Self-Realization Questionnaire by S.I.Kudinov [Kudinov, 2017].This instrument contains 101 questions with 6 options for answers: from “no” to “definitely yes”).The values of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for the test scales range from 0.72 to 0.78, with the test-retest reliability coefficient of 0.76 (p < .01).

Various components of emotional intelligence were assessed with the EmIn questionnaire by D.V.Lyusin [Lyusin, 2004].The test contains 46 statements evaluated on a 4-point Likert-wise scale).Cronbach’s alpha values for the test subscales range from 0.75 to 0.79.

“Big Five Inventory-2” (in the Russian adaptation of S.A.Shchebetenko [Kalugin, 2021]: 61 questions) assessed respondents’ major personal factors (Big Five).The test has Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84 — for raw scores and 0.85 — for centered scores, thus, indicating high internal consistency.The checklist of basic socio-demographic data included questions regarding gender, age, field of study and professional specialization, as well as of structural subdivision within the university, and the length of study / work.

Participation in the study was voluntary and no remuneration was paid to participants.Participants filled out the response forms of all measures individually.The respondents’ anonymity was ensured.The collected data were processed in the SPSS 26.0 package by means of the following statistical procedures.An unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare the groups of respondents on major variables, Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the direction and degree of relationships among variables, and multiple regression analysis was used to assess the relative contribution of various predictors to the distribution of the criterion variable of social self-realization.

Results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics for all variables and cross-correlations among them for the sample as a whole are summarized in Table 1.

First, we were interested in whether there are differences in the major variables between the working and studying groups, regardless of the age factor.There is a statistically significant relationship between age and professional experience (r = 0.459, p < .01), while professional experience (naturally higher for the working participants), but not age, is significantly positively correlated with several major variables, except for personality traits (their relatively stable nature throughout their life cycle is quite well documented).It should be noted that as the experience of professional activity is gradually acquired with time, the indicators of all types of self-realization decrease.

For the entire sample, the indicator of social self-realization (M = 57.37) is significantly lower than the indicators of personal (M = 79.42) and professional (M = 62.33) self-realization.Pairwise comparisons of social self-realization with the other two types are statistically significant (p < .001 and p = .013, respectively).The same pattern is preserved when the sample is divided into the working (53.20; 74.08; 57.67) and studying (60.24; 83.11; 65.54) groups of respondents.The numbers in parentheses reflect the average values of the subjective assessment of social, personal and professional self-realization (in this sequence) for these subgroups, respectively.Thus, H1 about the relatively low degree of social self-realization in this age group is supported.

These results are consistent with the pattern previously observed in many empirical studies.For example, when studying the priority areas of youth social activity, it was revealed that the most significant are personal (leisure-communicative activity and activity in the field of self-development) and professional (educational and developmental activity) self-realization, while social (spiritual-religious, voluntary and socio-political activity) is less significant in student population [Kostakova, 2013; Shamionov, 2019].

Other variables involved in the study, namely the participants’ personality characteristics and various indicators of their emotional intelligence, are within the ranges typical for this age group.

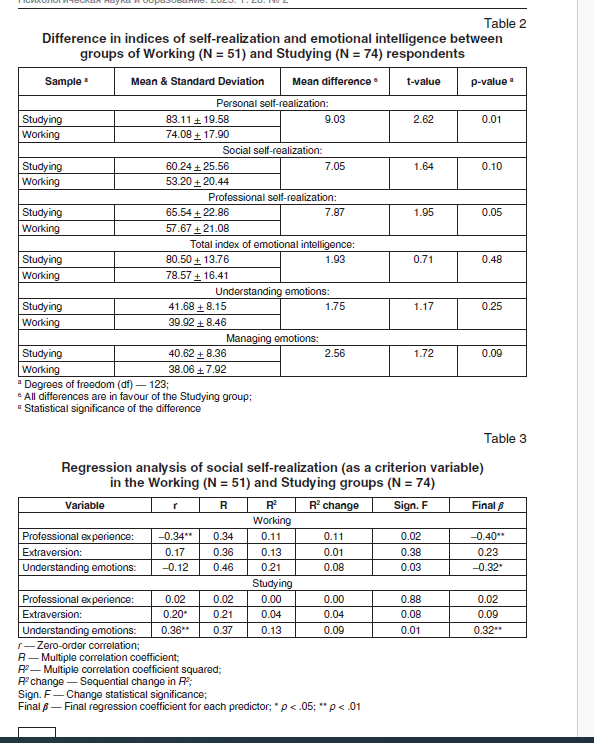

Table 2 summarizes the data of pairwise comparisons (between the two groups) of variables that have significant correlations with the indicator of professional experience.The absence of statistically significant differences in indicators of emotional intelligence reflects that the presence of this construct is relatively stable (compatible) throughout the entire sample — as the H2 hypothesis suggested.

In contrast, there are statistically significant (and approaching significance) differences in the levels of personal (p = .01) and professional (p = .05) self-realization, with higher values of both in the group of studying respondents, but not social self-realization (p = .10).In other words, social self-realization “sags” in comparison with the other two types of self-realization for both working and studying respondents.

No matter how characteristic of this age period this tendency may be, it requires an explanation, and if necessary (as low social self-realization could be associated with the risk of maladjustment), adequate compensation, including by means of psychological correction.

To better understand what factors influence the respondents’ subjective perception of their social self-realization, several models of hierarchical multiple regression analysis were tested with the social self-realization indicator as a dependent variable and professional experience, Big Five personality characteristics and some parameters of emotional intelligence as predictors — separately for the groups of working and studying respondents.

Only one model, using indices of ‘extraversion’ and ‘understanding emotions’ as predictors, revealed statistically significant results (Table 3).

The overall explanatory power of the model stands at 20.9% and 13.4% for the working and studying groups, respectively.Furthermore, the relationships found for these two groups were almost diametrically opposite.

Professional experience is a significant negative predictor of social self-realization among the working respondents (β = –0.40, p < .01), independently explaining up to 11.4% of the spread in values of the dependent variable, while for the studying respondents this factor is practically inconsequential (β = 0.02, ns).In both groups, ‘extraversion’ is a positive but not statistically significant predictor.For the studying respondents, this indicator appears as a trend, approaching a statistically significant value uniquely contributing to the explanatory power of the model 4.2% (p = .08).

Finally, ‘understanding emotions’ is a statistically significant predictor for both groups, but its contribution goes in the opposite direction.For those who combine work and study, it is negative (β = –0.32, p < .05) and explains 8.1% (p = .03) of variability of the dependent variable.The corresponding values for the indicator of ‘understanding emotions’ in non-working students are: β = 0.32 (p < .01) and 9.2% (p = .01).

Similar data are reported in [Davydova, 2019]: teachers with a high level of professional burnout, accumulated throughout a long but unsatisfying professional activity (i.e., long experience correlates with an increase in dissatisfaction) are characterized by a constantly reduced mood background and pronounced scepticism, and their activity (including socially oriented) ceases to be purposeful and productive.Their professional motivation consists predominantly of negative motives (fear of losing a job and the related payments, of been reprimanded, etc.).Such teachers think about how to radically change something in their lives for the better, but it is especially challenging for them due to the reduced ability to understand their own emotions and the emotions of other people.

Thus, as an essential part of the answer to the third research question, only the unique role of emotional intelligence received statistically significant support, although the nature of its relationship with other variables is fundamentally different for the groups of working and studying respondents.For the former, ‘understanding emotions’ (of their own and people around them) can make an additional contribution to a more acute awareness of the lack of demand for social pursuit in their professional activity — neither they themselves nor their colleagues attach much importance to behaviors not supported by pragmatic interests.Accordingly, high sensitivity to emotions allows them to feel it faster and perceive more accurately.On the contrary, for the latter group (who are not yet under the pressure to focus exclusively on their professional careers and are open to other types of socially-oriented activities), a higher level of understanding emotions can help determine which social activity and which partners for its implementation to choose and, thus, optimize the degree of involvement in it (benefit more from social activities and, as a result, experience higher degree of self-realization).

Conclusion

- The results obtained by the study are based on a sample with the predominance of females (86% — women and 14% — men), as well as young people who are not formally involved in social projects.This sample is fairly representative and has characteristics typical of most young adults in Russian higher education.This applies both to the variables common for the entire sample (personal characteristics, level of emotional intelligence and low degree of social self-realization), and for those characteristics that emphasize differences within the sample (higher rates of personal and professional self-realization among the studying compared to the working respondents).The role of professional experience (in contrast to age) is clearly observed in the differential dynamics of self-realization, but not in personal characteristics and not in the indicators of emotional intelligence.With an increase in professional experience, all types of self-realization (social, in particular) tend to decrease.

- The difference in the nature of the pair-wise relationships between the predicting variables and the level of social self-realization (as a criterion variable) in the groups of studying and working has been established.Professional experience is a significant negative predictor of the degree of social self-realization among working respondents.The ability to understand emotions reduces the degree of social self-realization among working respondents, but increases it among studying respondents.

- For both working and studying respondents, extraversion is a positive, but statistically insignificant predictor of social self-realization.

Low levels of social self-realization in young adults create potential challenges to their social and psychological adaptation, to the effectiveness of professional activities and interpersonal contacts.However, there are different ways to address this problem, including various methods of psychological correction.When carrying out some of these corrective measures with working youth, it is necessary to pay attention to the harmonization of the self-concept and the development of emotional intelligence, in particular, understanding one’s own and others’ emotions.

As young adults gain work experience, they may become disillusioned with their professional activities and develop professional burnout, excessive self-criticism, associated with the decreased social activity, initiative and perseverance.Early recognition of such tendencies by young people themselves (due to higher emotional intelligence and, in particular, a better ability to understand emotions) may allow them to seek earlier and more actively and to successfully find ways to compensate for the problems, for example, by dividing attention and directing efforts towards various complementary goals instead of concentrating them on a single one — such as, professional career or material well-being.

As part of the psychological and pedagogical support for young people in their student life, curators of study groups can be recommended to carry out activities aimed at involving students in socially useful, cultural, and sports activities, to form socio-centric motivation by using effective team building methods, and also by encouraging students to participate in start-ups and various business projects.

The effectiveness of such activities will be largely determined by the ability of students to reasonably balance them, find reliable partners and like-minded people, predict the success of their efforts based on the reaction of other people involved in joint projects and of their target audiences.With an increase in the level of emotional intelligence of students, their subsequent entrepreneurial self-efficacy increases, especially for those who pay more attention to the applied and innovative education [Wen, 2020].

Also, for psychologists who work with students, it makes sense to use applied techniques aimed at increasing the internal resource for self-realization, in particular, at developing emotional intelligence through the appropriate psychological training.

A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of emotional intelligence training confirms its potential benefits by reporting a statistically significant overall effect size of r = 51 [Hodzic, 2018].Moreover, emotional intelligence training promoted an increase in the indicator of understanding emotions significantly more than of the other scales (r = .69).It is possible that emotional intelligence training has the greatest effect on those competencies that are important for academic performance — several studies conducted in educational institutions confirm a greater increase in the participants’ ability to understand emotions.Emotional intelligence training programs have the potential of positively impacting academic performance and, indirectly — social and personal self-realization of young adults.

Without a doubt, among the most important directions the further research could aim at are the following:

(1) comparative analysis of indicators of social self-realization of volunteers and young people who do not take part in informal socially oriented events;

(2) comparison of data obtained on samples with different gender and professional experience compositions;

(3) more in-depth analysis of the nature of the relationships between social self-realization and personal psychological characteristics of respondents, including various aspects of their emotional and social intelligence.