Introduction

Relevance of this study on social identity as a factor of emigration behavior among students of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia is associated with increased emigration mobility of young people from the post-Soviet countries. The growth of young peopleꞌs emigration mobility requires finding the ways for these countries to retain valuable social capital. Frequently, researchers turn to the theory of planned behavior by Icek Ajzen [Ajzen, 1991] when studying emigration behavior. According to the theory of planned behavior, intention is a factor of readiness for certain behavior. Therefore, intention may be an indicator or predictor of emigration behavior [Tjaden, 2019]. However, the emigration intention is not always realized in the appropriate behavior. This suggests that there are different factors that influence the transition of intention to action. It is especially important to study not separate factors, but the holistic structure of the socio-psychological space in which the emigration intentions of young people are formed [Murashchenkova, 2021a]. In addition, it is important to carry out a cross-cultural analysis of these factors, as their contribution to the development of emigration behavior may differ in various cultural contexts.

The analysis of different types of social identity [Gritsenko, 2020; Nestik, 2017] as factors of emigration behavior is particularly significant in todayꞌs rapidly changing world, when people are in dire need of identification with groups seeking support and positive self-determination and self-respect. Positive perception of oneꞌs social group, satisfaction with membership in this group, desire to belong to it gives the person a feeling of psychological security and stability [TaJfel, 1986]. If the group to which a person belongs loses its attractiveness and/or has a low social status, they may seek to distance themselves from it both psychologically and physically, including emigration [Gritsenko, 1997]. Thus, the available research confirms the link between ethnic identity and emigration attitudes [Agadjanian, 2008; Caron, 2020]. Belonging to an ethnic minority and the degree of perceived discrimination can be factors influencing emigration behavior. The high level of civic identity, as the recognition of identification with the civil community and the significance of membership, can hinder the formation of emigration intentions [Marrow, 2020]. In its turn, the high uncertainty of civic identity, on the contrary, may reinforce them [Jung, 2019]. A high level of global identity, as an identification with humanity and commitment to cosmopolitan values, can stimulate emigration intentions [Sychev, 2021]. Ethnic, civic, and global identities are thus psychological constructs that may encourage or discourage the emigration intentions of youngsters.

The theoretical analysis which we conducted shows that most studies focus on ethnic, civic, and/or global identities as separate factors of emigration intentions. As far as we know, there is also a lack of research that assesses a cross-cultural analysis of the components of ethnic, civic, and global identities as predictors of emigration intentions of the youth from post-Soviet countries, whose cultures have both similar and different features. Therefore, the study of relationships between the system of cognitive and emotional components of ethnic, civic, and global identities and emigration intentions and behavior to realize these intentions among the youth of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia is important for elucidating the migration processes in the post-Soviet space. After the dissolution of the USSR these countries, on the one hand, sought to maintain close socio-economic and cultural ties, as evidenced by the creation of a customs union, a single economic space, and other intergovernmental organizations. On the other hand, each of these countries developed their own political, economic, and sociocultural realities that influence the socialization of the young generation, and their identity and aspirations [Dergunova, 2017; Dyrina, 2021; Nysanbaev, 2019]. In this regard, it is important to find the answer to the question: are there differences in the links between the emigration intentions and behavior of young people from Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia and cognitive and emotional components of their ethnic, civic and global identities?

Method

Participants and Procedure. The sample included 208 students from Belarus (75% female), 200 from Kazakhstan (74% female), and 250 from Russia (75% female) aged between 18 and 25. The mean age (standard deviation) for the Belarusian sample was 19.80 (1.91), for the Kazakhstani sample 20.54 (1.89), and for the Russian sample 20.03 (1.51). Among Russians, 87% considered themselves as Russians, among Kazakhstanis 54% considered themselves as Kazakhs, and among Belarusians 94% identified themselves as ethnic Belarusians. Students majoring in humanities, engineering, and economics participated in the study. They were students from the universities of Minsk, Vitebsk, Grodno (Belarus), Nur-Sultan, Pavlodar, Ust-Kamenogorsk (Kazakhstan), and Moscow, Saint Petersburg, Penza, Smolensk, Omsk, Khabarovsk (Russia).

Empirical data were collected in an anonymous survey on the anketolog.ru platform from January 2021 to April 2021.

Measures. We developed six items in order to assess emigration intentions and emigration behavior of students. We relied on the basic principles of questionnaire design according to the theory of the planned behavior by Ajzen [Ajzen, 2002; Ajzen, 1991]. We measured the emigration intentions with three items: “I plan to move to another country in the next 5 years”, “I want to live in another country in the next 5 years”, “I am ready to move abroad in the next 5 years”. We assessed the behavior of students aimed at realization of emigration intention with three items: “I have already been actively developing an action plan for moving abroad”, “Currently, I am trying to get as much information as possible from different sources about the country of the proposed move”, “I have already been actively cooperating with those who can help me move abroad”. The respondents indicated their level of agreement with the items using a 6-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alphas for the emigration intentions and emigration behavior scales were Belarusians α = 0.90/0.86; Kazakhstanis α = 0.91/0.89; Russians α = 0.88/0.87, respectively.

For the measurement of ethnic identity, we used the Questionnaire of positivity and uncertainty of ethnic identity estimation by A.N. Tatarko and N.M. Lebedeva [Tatarko, 2011]. The questionnaire includes two scales that measure the emotional and cognitive components of ethnic identity. Cronbach’s alphas for scales of the valence of ethnic identity and the certainty of ethnic identity were Belarus 0.64/0.57, Kazakhstan 0.60/0.59, and Russia 0.65/0.59, respectively.

The Identification with All Humanity Scale (IWAH) by S. McFarland [Nestik, 2017] was used to measure civic and global identities. The Scale consists of nine questions with five possible options. Using this Scale, we measured respondents’ attitudes towards their co-citizens and humanity as a whole. The Questionnaire includes two sub-scales. The first sub-scale measures the cognitive component of identity, and the second sub-scale measures its affective component. Cronbach’s alphas for sub-scales of the cognitive and affective components of global identity and for sub-scales of the cognitive and affective components of civic identity were Belarus 0.82/0.85/0.79/0.83, Kazakhstan 0.83/0.88/0.87/0.85, and Russia 0.79/0.84/0.74/0.83, respectively.

Statistical Analysis. We used SPSS Statistics version 23 and AMOS version 23 for statistical analysis. We calculated the psychometric measures of the scales (Cronbach’s alpha). In addition, we calculated descriptive statistics and the significance of mean value differences (Student’s t-test) for each basic variable across the three samples. We used Multi-Group Structural Equation Modeling (MGSEM) for testing the assumptions. We performed multiple regression analysis with gender, age, economic status, nationality, level of religiosity, knowledge of foreign languages, experience of international mobility, and social ties abroad as predictors of all other basic variables. We used the non-standardized residuals of these analyses in the remaining analyses. We built our structural models while controlling for these variables by using these residual scores. The dependent variables in the models were emigration intention and emigration behavior. The dependent variables were modeled as two latent factors, each represented by three measured variables. Separate models were made for each dependent variable. Predictors in the models were the cognitive and emotional components of global, civic, and ethnic identities.

Results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and the significance of mean value differences of basic variables in the three samples. We discovered statistically significant differences in the level of emigration intentions and emigration behavior among students from Russia compared to students from Belarus and Kazakhstan (Table 1).

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics

|

Variables |

Min |

Max |

Belarus1 N=208 |

Kazakhstan2 N=200 |

Russia3 N=250 |

|||

|

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

|||

|

Ethnic identity |

||||||||

|

Certainty |

1 |

6 |

4.79 |

0.94 |

4.96 |

1.06 |

4.83 |

0.91 |

|

Valence |

1 |

6 |

4.612,3 |

1.09 |

5.091 |

1.04 |

5.121 |

0.92 |

|

Civic identity |

||||||||

|

Cognitive component |

5 |

20 |

14.043 |

3.45 |

14.103 |

3.72 |

13.241,2 |

3.33 |

|

Affective component |

5 |

25 |

17.863 |

4.23 |

18.073 |

4.38 |

16.571,2 |

4.02 |

|

Global identity |

||||||||

|

Cognitive component |

5 |

20 |

12.572 |

3.53 |

13.291,3 |

3.65 |

12.382 |

3.22 |

|

Affective component |

5 |

25 |

17.062 |

4.25 |

18.101,3 |

4.21 |

17.042 |

4.16 |

|

Emigration intention |

||||||||

|

1. I plan to move to another country in the next 5 years |

1 |

6 |

3.143 |

1.52 |

3.163 |

1.65 |

2.801,2 |

1.37 |

|

2. I want to live in another country in the next 5 years |

1 |

6 |

3.53 |

1.70 |

3.55 |

1.75 |

3.26 |

1.56 |

|

3. I am ready to move abroad in the next 5 years |

1 |

6 |

3.12 |

1.71 |

3.06 |

1.86 |

2.85 |

1.66 |

|

Emigration behavior |

||||||||

|

4. I have already been actively developing an action plan for moving abroad |

1 |

6 |

2.583 |

1.57 |

2.553 |

1.60 |

2.211,2 |

1.33 |

|

5. Currently, I am trying to get as much information as possible from different sources about the country of the proposed move |

1 |

6 |

2.863 |

1.68 |

2.783 |

1.73 |

2.431,2 |

1.47 |

|

6. I have already been actively cooperating with those who can help me move abroad |

1 |

6 |

2.223 |

1.33 |

2.263 |

1.45 |

1.961,2 |

1.27 |

Note: 1 the statistically significant difference with Belarusians; 2 the statistically significant difference with Kazakhstanis; 3 the statistically significant difference with Russians (Student’s t-test).

Table 2

Invariance for Multi-Group Model of the Relationship Between

Emigration Intentions and Global, Civic,

and Ethnic Identities Among Students of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia

|

Model |

CFI |

RMSEA |

AIC |

PCLOSE |

Chi-square |

df |

p |

|

Unconstrained* |

0.999 |

0.009 |

289.935 |

1.000 |

37.935 |

36 |

0.381 |

|

Structural weights** |

1.000 |

0.000 |

262.509 |

1.000 |

54.509 |

58 |

0.606 |

Note. CFI – comparative fit index; RMSEA – root mean square error of approximation; PCLOSE – p of Close Fit. AIC – Akaike information criterion; ∆CFI < 0.01; * — configural invariance; ** — metric invariance.

Table 3

Invariance for Multi-Group Model of the Relationship Between

Emigration Behavior and Global, Civic,

and Ethnic Identities Among Students of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Russia

|

Model |

CFI |

RMSEA |

AIC |

PCLOSE |

Chi-square |

df |

p |

|

Unconstrained* |

0,999 |

0,012 |

291,476 |

1,000 |

39,476 |

36 |

0,317 |

|

Structural weights** |

1,000 |

0,002 |

266,132 |

1,000 |

58,132 |

58 |

0,470 |

Note. CFI – comparative fit index; RMSEA – root mean square error of approximation; PCLOSE – p of Close Fit. AIC – Akaike information criterion; ∆CFI < 0.01; * — configural invariance; ** — metric invariance.

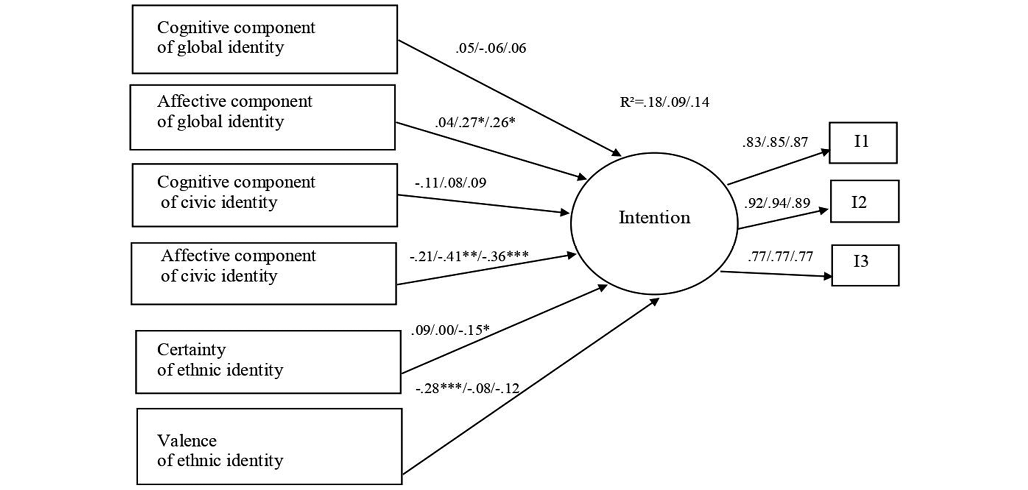

Fig. 1. Multi-Group (Unconstrained) Model of the Relationship Between Emigration Intentions and Components of Global, Civic, and Ethnic Identities Among Students of Belarus/Kazakhstan/Russia: I1 — “I plan to move to another country in the next 5 years”, I2 — “I want to live in another country in the next 5 years”, I3 — “I am ready to move abroad in the next 5 years”; * — p <0.05; ** — p <0.01; *** — p <0.001

Russian students, to a lesser extent than Belarusian (p=0.01) and Kazakhstani (p=0.01) students, plan to move to another country in the next 5 years. At the same time, Russians are less likely than Belarusians and Kazakhstanis to implement their emigration intentions. This manifests itself in a lower propensity to develop an action plan for moving (p=0.01/p=0.02); to search for information about the country of intended emigration (p=0.00/p=0.02); and to interact with people who can help to move (p=0.04/p=0.02). There are no statistically significant differences among Belarusian and Kazakhstani students in these parameters. However, emigration intentions are more pronounced than the behavioral manifestations of emigration activity in three samples.

Data in Table 1 shows that Belarusian students are less positive about their ethnic affiliation compared to Kazakhstani (p=0.00) and Russian (p=0.00) students. Kazakhstanis and Belarusians identify themselves more than Russians with the citizens of their country (p=0.00/p=0.00) and are more positive towards their civic community (p=0.00/p=0.00). In addition, Kazakhstani students, in comparison with Belarusian and Russian students, are more aware of their identity with people of the whole world (p=0.04/p=0.00) and more positively assess this identity (p=0.01/p=0.00).

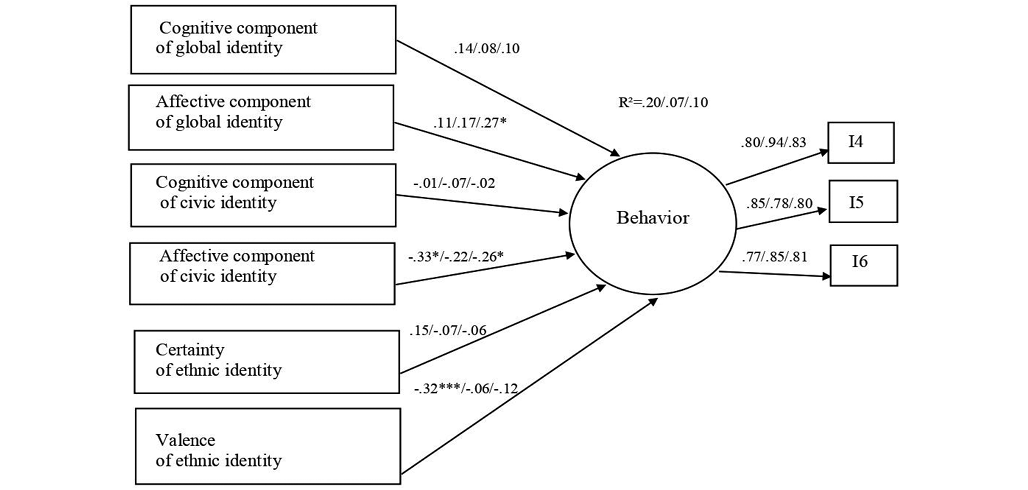

Figures 1 and 2 show multi-group models that demonstrate differences in the relationships between emigration intention and behavior and components of ethnic, civic, and global identities among students from the three countries.

Fig. 2. Multi-Group (Unconstrained) Model of the Relationship Between Emigration Behavior and Components of Global, Civic, and Ethnic Identities Among Students of Belarus/Kazakhstan/Russia: I4 — “I have already been actively developing an action plan for moving abroad”, I5 — “Currently, I am trying to get as much information as possible from different sources about the country of the proposed move”, I6 — “I have already been actively cooperating with those who can help me move abroad”; * — p <0.05; ** — p <0.01; *** — p <0.001

All items that measured emigration activity were included into latent constructs with statistically significant estimates (see Figures 1 and 2). Both models (see Tables 2 and 3) showed acceptable fit. Since configural and metric invariance are present (∆CFI < 0.01), we can compare regression relationships among samples of the three countries.

The predictors contribute most to the explanation of emigration intentions in samples from Russia and Belarus than in the sample from Kazakhstan (see Figure 1). At the same time, emigration behavior is more determined by the predictors in the Belarusian sample than in the Kazakhstani and Russian samples (see Figure 2).

We found out that the regression links between the emigration intentions of students and the identities have their own characteristics in three samples. Among Belarusian students the negative estimation of their own ethnicity predicts emigration intentions (β=0.32, p=0.00). Among the students of Kazakhstan and Russia, emigration intentions are linked to with a positive attitude towards the global community as a whole (β=0.27, p=0.04; β=0.26, p=0.02) and negative attitude towards the citizens of their country (β=-0.41, p=0.01; β=-0.36, p=0.00). In addition, Russian students with emigration intentions have vague ideas about their own ethnicity (β=-0.15, p=0.03).

Regression relationships between the emigration behavior of student activity and their identities are also specific in three samples. Emigration behavior among Belarusian students is related to negative attitude towards the citizens of their country (β=-0.33, p=0.02) and to their own ethnicity (β=-0.32, p=0.00). Among Russian students, this behavior is also linked to negative attitude towards the citizens of their country (β=-0.26, p=0.02), but combined with positive attitude towards the global community of people as a whole (β=0.27, p=0.02). In this case, no statistically significant connections have been found among Kazakhstani students.

Discussion

Similar to our previous study [Murashchenkova, 2021], the results confirm that emigration intentions expressed by student youth are most often associated with a passive-preferred strategy that is rarely implemented in specific emigration behavior. This may be due to the specifics of the student sample. Students are oriented towards completion of their education and can postpone action on the implementation of emigration intentions. However, the differences in emigration activity between Belarusian and Kazakhstani students compared to Russian students may be indicative of the greatest dissatisfaction of the student youth of Belarus and Kazakhstan with their conditions in the country. The main reason for the dissatisfaction of Belarusian youth, for example, may be the socio-political situation that has developed in the country since the presidential election in August 2020. According to the experts, the situation in Belarus is characterized by instability and a protracted crisis [Dyrina, 2021].

The links we have found in the study between the components of ethnic, civic, and global identities and the emigration activities of Belarusian, Kazakhstani, and Russian students have both similarities and differences. The similarity is evident in the links between the emotional component of civic identity and emigration activity among students in the three studied countries. Thus, reducing students’ positive attitudes and decreasing students’ identification with citizens of their own country may encourage emigration activity among students. However, while for Kazakhstani and Russian respondents the affective component of civic identity is a predictor of emigration intentions, for Belarusian respondents it is a predictor of emigration behavior. That is, the low degree of identification of Belarusian students with the citizens of the country contribute to the manifestation not of passive-preferred, but of an actively implemented emigration strategy. In general, the results show that the positive assessment of oneꞌs own nationality plays a universal role in preventing emigration activity. These results are expected and consistent with other studies, according to which it is usually those young people who do not identify themselves with the citizens of their country and have a low level of civic activity [Dergunova, 2017] go abroad.

There are differences between the components of ethnic and global identities and the emigration activities of Belarusian, Kazakhstani and Russian students. In the Belarusian sample we discovered no link between global identity and emigration activity. However, the similar type of the relationship between the sense of community with all humanity and emigration activity is revealed among student youth of Kazakhstan and Russia: the increase of global identity is accompanied by a rise of emigration activity of Kazakhstani and Russian students. At the same time, the affective component of the global identity of Kazakhstani students is linked only to emigration intentions. However, among Russian students, the affective component of the global identity is related to both emigration intention and behavior and respectively acts as a predictor of the active emigration strategy. Accordingly, for Russian student youth, positive identification with humanity can contribute not only to the formation of intentions of emigration, but also to actions for their implementation that is not found in Kazakhstani and Belarusian students.

At the same time, only among Belarusian students, a link was found between the emotional component of ethnic identity and emigration activity. Reducing attachment to oneꞌs ethnic group can stimulate the development of both emigration intentions and behavior among Belarusian students. This evidence corresponds to the results of a study according to which ethnicity is not relevant for today’s Belarusian students and they prefer to identify with groups unrelated to this parameter [Kazarenkov, 2020]. This trend of diffusion of the ethnic identity among Belarusian students can stimulate the growth of emigration activity, both in the form of passive-preferred and actively implemented strategies. In turn, we found the link between emigration intentions and uncertainty of ethnic identity only among Russian students. Diffused representations of oneꞌs own ethnicity of Russian student youth can stimulate the search for groups to identify oneself with, including through the formation of emigration intentions. Thus, according to the results of this study, the affective rather than the cognitive components of ethnic, civic, and global identities play a major role in the formation of emigration activity of students of the three countries.

Conclusion

The results of the research allow us to answer positively the question posed at the beginning of the article. Indeed, there are differences in the links between affective and cognitive components of ethnic, civic, global identities, and emigration activities among Belarusian, Kazakhstani, and Russian students. This confirms the importance of taking into account the civic and socio-cultural contexts in order to prevent the emigration activity of young people and to preserve valuable human capital.

Despite some limitations (correlation design, females predominate in the sample, and relied on self-report data), the results of the study can be used in the field of youth policy of three countries to predict and prevent mass emigration of youth. The study also enriches knowledge in the field of manifestation of various socio-psychological phenomena among citizens of the post-Soviet countries. We can make an additional theoretical and practical contribution by conducting a comparative analysis of this system of predictors of emigration activity among students and representatives of other socio-demographic groups of the post-Soviet countries population in the future.