Introduction

Epidemiological studies showed that 9.6% of people in the general population meet the criteria for bodily distress syndrome and 4.5% meet the criteria for somatic symptom disorder [Häuser, 2020]. For chronic somatic diseases, 98% of respondents reported at least one disturbing somatic symptom and 45% reported six or more such symptoms [Glise, 2014]. These statistics are largely similar to the results of epidemiological studies in Russia, which indicate that the prevalence of psychosomatic disorders in Russian general medical practice is 30-45% [Andryushchenko].

There is compelling evidence for the significant role of somatization in people's mental and physical health. Somatization is the result of psychological discomfort, which some people tend to express through bodily symptoms. Depression, anxiety, and stress can stimulate the development of somatic symptoms, especially among people with high levels of neuroticism and agreeableness [Mostafaei, 2019]. Moreover, somatic symptoms often become persistent, progressing from functional to organic and sometimes even leading to disability [Rosendal, 2017]. Patients with medically unexplained symptoms stayed 41% longer in general hospitals compared to the statistical average duration of hospitalizations [Hatcher, 2011].

Other evidence provides studies confirming that somatoform disorders are one of the most serious risks for premature mortality [Plana-Ripoll, 2020]. Furthermore, 13-67% of respondents with somatoform disorders have reported suicide attempts [Torres, 2021].

In 2013, a systematic review of 40 instruments measuring somatic symptoms was published [Zijlema, 2013]. Based on psychometric properties and criteria of convenience and burden on respondents, the researchers concluded that the following two instruments were the most successful measures of somatic symptoms:

- The Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) is a measure assessing the overall somatization index and 15 specific somatic symptoms (e.g., stomach pain, back pain, headaches, dizziness, fainting spells, feeling heart pound or race, trouble sleeping) [Kroenke, 2002]. The PHQ-15 is a short version of the PHQ examining eight disorders according to DSM-IV criteria: major depressive disorder, panic disorder, bulimia nervosa, other depressive disorder, other anxiety disorder, probable alcohol abuse or dependence, binge eating disorder, and somatoform disorder [Spitzer, 1999]. The PHQ-15 can measure somatoform disorder in both the general population and in groups of respondents with mental and physical diseases [Dadfar, 2020; Kocalevent, 2013; Kroenke, 2002].

- Somatization subscale from the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R) is a measure assessing the overall somatization index [Derogatis, 1994]. This subscale can be used both independently and as part of the other SCL-90-R scales. In addition to somatization, the SCL-90-R measures symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. The SCL-90-R also examines three general measures of psychological distress, such as global severity index, positive symptom distress, and positive symptom total. The full version of the SCL-90-R, consisting of 90 items, has been translated and adapted into Russian [Tarabrina].

The PHQ-15 has not been translated and standardized for Russian-speaking respondents, although its advantages over the SCL-90-R are that it is suitable for DSM-IV assessment of somatoform disorders and can be used as a screening and monitoring of medically unexplained symptoms [Liao, 2016]. In this regard, the current study was aimed to standardize the Russian version of the PHQ-15.

Method

Procedure. The participants were recruited with the help of Anketolog. The volunteers of 18 years of age or older who had no chronic diseases and were not registered with a narrow specialty physician were invited to participate in the study. The participants completed written informed consent describing the aim of this study and mentioning the possibility to refuse participation.

Participants. Respondents (N=1157) completed the questionnaire, including 598 (51.7%) females and 559 (48.3%) males in three age categories: 313 (27.1%) respondents aged 18-34, 550 (47,5%) respondents aged 35-49, and 294 (25.4%) respondents aged 50-71.

Instruments. The participants completed the following instruments:

- The Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) was translated into Russian by two bilingual experts through direct translation [Behr, 2017].

- The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) contain 21 items assessing depression (e.g., “I couldn't seem to experience any positive feeling at all”), anxiety (e.g., “I felt that I was using a lot of nervous energy”) and stress (e.g., “I found it difficult to relax”) [Zolotareva, 2020].

Ethical considerations. Permission to standardize the Russian version of the PHQ-15 was obtained from the HSE Institutional Review Board.

Results

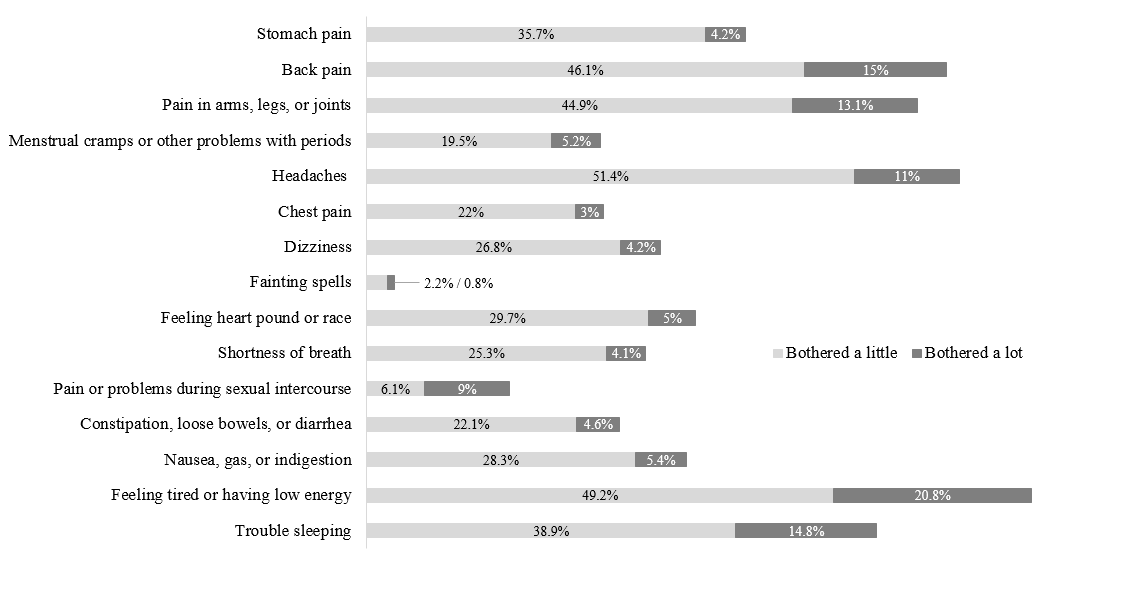

Ninety-one percent of the participants reported experiencing at least one somatic symptom during the past four weeks. For example, 70% of the participants experienced feeling tired or having low energy, 62.4% experienced headaches, 61.1% experienced back pain, 58.1% experienced pain in arms, legs or joints, 53.7% experienced trouble sleeping, 39.9% experienced stomach pain, 34.7% experienced feeling heart pound or race, 33.7% experienced nausea, gas, or indigestion, 31% experienced dizziness, 29.5% experienced shortness of breath, 26.7% experienced constipation, loose bowels, or diarrhea, 25.1% experienced chest pain, 6.9% experienced pain or problems during sexual intercourse, and 3% experienced fainting spells. In addition, 24.7% of females reported menstrual cramps or other problems with periods. The prevalence and severity of somatic symptoms are presented in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Prevalence and severity of somatic symptoms in the general Russian-speaking population

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and accumulated percentages for the Russian version of the PHQ-15 (see Table 1). Based on descriptive statistics, test norms (M = 6.73, SD = 4.82) were calculated, which can be used for practical and research purposes as indicators of low (0-4 points), medium (5-9 points), or high somatization (≥ 10 points). Thus, 38.6% of the participants had low, 33.4% had medium, and 28% had high psychosomatic burden.

Table 1

Standardization of the Russian version of the PHQ-15

Note: n = number of respondents; M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

|

Балл по PHQ-15 |

Общая выборка (n=1157) |

Женщины (n=598) |

Мужчины (n=559) |

||||

|

18—34 (n=151) |

35—49 (n=298) |

50—71 (n=149) |

18—34 (n=162) |

35—49 (n=252) |

50—71 (n=145) |

||

|

Описательная статистика |

|||||||

|

M |

6,73 |

6,48 |

8,57 |

7,42 |

3,72 |

6,34 |

6,51 |

|

SD |

4,82 |

4,48 |

5,08 |

4,51 |

3,64 |

4,59 |

4,66 |

|

Суммарный балл (накопленные %) |

|||||||

|

0 |

9,0 |

5,3 |

4,4 |

2,7 |

25,3 |

10,3 |

8,3 |

|

1 |

14,5 |

11,9 |

7,7 |

8,1 |

34,0 |

16,7 |

12,4 |

|

2 |

21,3 |

19,9 |

11,1 |

12,8 |

43,8 |

25,4 |

20,0 |

|

3 |

29,3 |

27,8 |

18,8 |

22,1 |

54,3 |

30,2 |

30,3 |

|

4 |

38,6 |

40,4 |

25,5 |

32,2 |

66,0 |

38,5 |

40,0 |

|

5 |

46,8 |

49,7 |

31,5 |

44,3 |

72,2 |

48,0 |

47,6 |

|

6 |

53,9 |

54,3 |

37,9 |

47,7 |

81,5 |

57,1 |

56,6 |

|

7 |

59,6 |

63,6 |

42,6 |

51,7 |

86,4 |

62,7 |

62,8 |

|

8 |

66,1 |

71,5 |

51,0 |

57,7 |

90,1 |

68,7 |

69,0 |

|

9 |

72,0 |

75,5 |

58,4 |

66,4 |

92,0 |

74,6 |

75,2 |

|

10 |

77,3 |

81,5 |

64,8 |

72,5 |

93,8 |

80,2 |

80,0 |

|

11 |

82,8 |

86,1 |

71,1 |

79,2 |

96,9 |

84,5 |

88,3 |

|

12 |

87,2 |

89,4 |

78,2 |

85,2 |

97,5 |

89,3 |

90,3 |

|

13 |

90,5 |

92,1 |

81,9 |

91,3 |

98,1 |

94,0 |

91,0 |

|

14 |

93,0 |

94,7 |

86,2 |

95,3 |

98,8 |

94,8 |

93,1 |

|

15 |

95,2 |

97,4 |

90,9 |

96,0 |

99,4 |

96,4 |

94,5 |

|

16 |

96,4 |

97,4 |

93,6 |

97,3 |

99,4 |

97,2 |

95,2 |

|

17 |

97,8 |

97,4 |

96,0 |

98,7 |

99,4 |

98,4 |

97,9 |

|

18 |

98,5 |

97,4 |

97,7 |

98,7 |

99,4 |

99,2 |

99,3 |

|

19 |

99,0 |

98,7 |

98,3 |

99,3 |

99,4 |

99,6 |

99,3 |

|

20 |

99,4 |

100,0 |

98,7 |

99,3 |

100,0 |

99,6 |

99,3 |

|

21 |

99,5 |

100,0 |

98,7 |

99,3 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

99,3 |

|

22 |

99,7 |

100,0 |

99,3 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

99,3 |

|

23 |

99,9 |

100,0 |

99,7 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

|

24 |

99,9 |

100,0 |

99,7 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

|

25 |

99,9 |

100,0 |

99,7 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

|

26 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

|

27 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

|

28 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

|

29 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

|

30 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

100,0 |

Females (M = 7.75, SD = 4.52) showed more frequent and severe somatic symptoms compared to males (M = 5.63, SD = 4.52). The participants aged 35-49 (M = 7.55, SD = 4.99) demonstrated more frequent and severe somatic symptoms compared to the participants aged 18-34 (M = 5.05, SD = 4.29) and participants aged 50-71 (M = 6.97, SD = 4.60). These patterns were statistically significant for both gender (t [1154.946] = 7.71, p < 0.001, d = 0.45) and age (F [2.1154] = 28.52, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05).

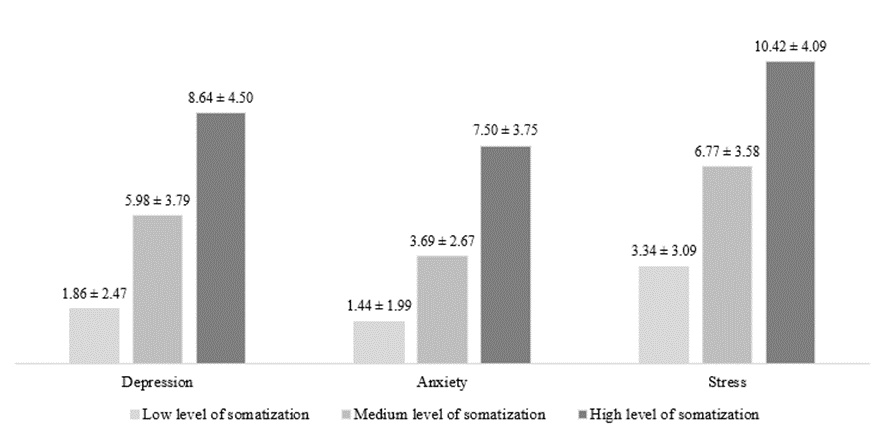

Depression (F [2.1143] = 332.16, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.37), anxiety (F [2.1143] = 434.18, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.43), and stress (F [2.1154] = 369.05, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.39) increased with the growth of number and severity of somatic symptoms (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Degree of psychological distress among respondents with different levels of somatization

Discussion

The key result of this study was the standardization of the Russian version of the PHQ-15. The adapted measure can categorize somatic symptoms in the general Russian-speaking population in terms of low (0-4 points), medium (5-9 points), and high degree of psychosomatic burden (≥ 10 points). These score ranges fully correspond to the tertiles identified during the development of the original measure [Kroenke, 2002] and later confirmed during the adaptation of the German version of the PHQ-15 [Kocalevent, 2013].

These tertiles highlighted that 28.2% of the Russian-speaking population had high degree of somatization and 91% of the participants complained of having at least one somatic symptom bothering them in the past four weeks. These rates of psychosomatic burden surpassed typical patterns associated with the prevalence of somatic symptoms in the general population [Toussaint, 2020] and can be explained by the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological and somatic health. The pandemic increased specific anxiety associated with the fear of contracting a coronavirus infection and contributed to the development of somatization in the general population [Shevlin, 2020]. Next, symptoms of coronavirus infection have similarities with functional somatic syndromes that develop in response to viral infection and occur in a type of medically unexplained symptoms [Ballering, 2021]. Finally, the lifestyle of many people during the COVID-19 pandemic changed, which may be associated with an objective increase in physical symptoms. Experts estimated that at the beginning of the pandemic the number of steps dropped from 10.000 to 4.600 per day and the time spent in front of phone, laptop and TV screens more than doubled to more than 5 hours per day [Giuntella, 2021].

Gender- and age-specific characteristics of somatization were also found in the general Russian-speaking population. Thus, the most frequent and severe somatic symptoms were reported by females and respondents aged 35-49 years. Previous studies showed that females are more likely to have medically unexplained symptoms than males, except for pain or problems during sexual intercourse [Beutel, 2019].

The relationship between age and somatization has more complex patterns. The traditional notion that there is a natural increase in the prevalence and severity of somatic burden with age has indeed been empirically confirmed [Beutel, 2019]. Moreover, researchers periodically encounter unexpected patterns where the greatest psychosomatic burden is observed either in the youngest respondents or in so-called «middle-aged» individuals [Nummi, 2017]. The geography of these studies suggests that cross-cultural differences between respondents are a possible reason for the contradictory data.

Finally, this study found that individuals with high psychosomatic burden had high rates of psychological distress, which is consistent with the previously found universal associations of somatization with perceived stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms [Bohman, 2018; Shangguan, 2021; Zheng, 2021].

The current study has at least two limitations. The first limitation concerns its population character and obliges further standardization of the Russian-language version of the PHQ-15 on clinical samples. K. Kroenke and his colleagues, who developed and validated the original version of the scale, found that among patients seeking primary care, the range of PHQ-15 scores is located within quintiles rather than tertiles [Kroenke, 2002]. The range of PHQ-15 scores was redistributed as follows: somatization was considered minimal at 0-4 points, low at 5-9 points, moderate at 10-14 points, and high at 15-30 points. These quintiles need to be tested on clinical Russian-speaking samples, but because of their universality can be used with caution for counseling purposes.

The second limitation is that this study involved adult respondents, whereas the PHQ-15 has been successfully used to screen and monitor for medically unexplained symptoms among adolescents and children over 7 years of age [Marwah, 2016].

Conclusions

- Ninety-one percent of the participants reported having at least one somatic symptom that had bothered them in the past four weeks.

- More than half of the participants reported feeling tired or having low energy (70%), headaches (62.4%), back pain (61.1%), pain in arms, legs, or joints (58.1%), and trouble sleeping (53.7%).

- Somatization in the general Russian-speaking population had gender- and age-specific characteristics. The most frequent and severe somatic symptoms were experienced by females, as well as respondents aged 35-49.

- High rates of perceived stress, depressive and anxiety symptoms were found in 28.2% of the participants with high psychosomatic burden.

- The Russian version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15) has been successfully standardized and can be recommended for use as a screening and monitoring measure of medically unexplained symptoms.