Introduction

University education is a period of substantial—and often challenging—change in students’ lives. Numerous studies demonstrate that a high level of academic and non-academic stress is an integral part of higher education worldwide (Basyuk, Malykh, & Tikhomirova, 2022; Sharp & Theiler, 2018). In addition to adapting to new social and academic environments, many students find themselves living away from home for the first time and must cope with stress without their previous social support networks. All these factors increase the risk of mental health problems, which may lead to academic underachievement (Zhang, Peng, & Chen, 2024), mental disorders (Auerbach et al., 2018), and suicidal behavior (Mortier et al., 2018).

Institutions of higher education (hereinafter referred to as universities) have a unique opportunity to influence the health and psychological well-being of both students and university staff. One possible mechanism for achieving this is the establishment of dedicated psychological services within universities.

At present, psychological services are not mandatory structural units in Russian universities, and the provision of psychological assistance in higher education institutions—unlike in general education—is not specifically regulated by the Federal Law “On Education.” Therefore, the formats of their operation may vary widely. A professional standard for psychologists working in higher education institutions was also absent in Russia at the time this article was prepared. Nevertheless, the Concept for the Development of a Network of Psychological Services in Higher Education Institutions in the Russian Federation (2022) outlines the implementation of state policy in developing a system of psychological support within universities. The main goal of this initiative is formulated as “the organization of qualified psychological assistance for students and employees of every higher education institution.” Thus, the long-term vision implies that psychological support services will eventually be available in every university.

Although the history of psychological services in Russia spans more than two decades (Makarova, 2017), this practice has so far been described and conceptualized only fragmentarily. Its understanding as an emerging social institution is only beginning to take shape (Metelkova, 2024).

In recent years, research has begun to focus on students’ attitudes toward university psychological services, as students represent their primary potential beneficiaries. These studies show that although the demand for psychological help among students is quite high (Antonova, Eritsyan, & Tsvetkova, 2021), there are numerous attitudinal barriers that hinder help-seeking. For instance, seeking psychological assistance is often perceived as a socially disapproved behavior (Eritsyan et al., 2021). Moreover, several specific biases exist toward university-based psychological services: students may perceive free counseling as low-quality or consider the university affiliation of the service a threat to the confidentiality of the information they share (Antonova, Dubrovsky, & Eritsyan, 2021).

At the same time, there is a lack of empirical data on what constitutes university psychological services in Russia—how they are organized, and to what extent specific practices and risks are prevalent within them. Experts identify a variety of organizational models for psychological services and analyze the potential risks associated with different formats (Metelkova, 2024). However, no reliable quantitative data have yet been presented that would allow for a comprehensive characterization of the current state of development of psychological services in Russian higher education institutions. A recent quantitative study provides a detailed description of the situation based on a sample of pedagogical universities (Ulyanina et al., 2024); however, it remains unclear to what extent these findings can be generalized to other types of universities.

At the same time, data obtained through regular, representative quantitative studies serve as an indispensable foundation for managerial decision-making and for improving the federal network of university psychological services (Basyuk, Malykh, & Tikhomirova, 2022). The present study aims to provide a quantitative description of how psychological support is organized in Russian universities.

Materials and methods

The first nationwide study of existing psychological services in higher education institutions in Russia was conducted by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation in collaboration with the Russian Academy of Education during the summer and autumn of 2022 in the form of an online survey. Invitations to participate were sent directly to all accredited universities in the Russian Federation (a full census sample). The achieved sample size included 479 universities, representing 39% of all higher education institutions in the country.

The university representative most informed about the activities of the psychological service was asked to complete the online survey. The questionnaire included items regarding the organizational form of the service, its main areas of activity, available resources, and other operational characteristics. In cases where a university did not have a psychological service or its analogue, respondents were asked questions about plans or prospects for establishing one.

Statistical data processing included the calculation of simple distributions and measures of central tendency. The study statistically assessed the relationships between the organizational features of psychological services and the characteristics of the universities to which they belong—such as inclusion in the “Priority 2030” and “Top 5-100” rankings, legal status (private or public), ministerial affiliation (the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Russia or another governing body), and institutional type (main campus or branch).

In addition, the analysis examined the relationships between the characteristics of the services’ activities and factors such as their duration of existence, degree of integration into educational activities (for example, using the service as a practicum base for psychology students), and the legal form of the service. Relationships were assessed using contingency tables (Pearson’s Chi-square test; Fisher’s exact test).

Results

The majority of universities that participated in the study (83,9%) reported that they had an operating psychological service. It is reasonable to assume that this proportion may be somewhat overestimated and may not fully reflect the actual prevalence of psychological services in Russian universities—institutions already engaged in this type of activity may have been more likely to participate in the survey, while those without such services may have ignored it due to its perceived irrelevance. At the same time, it can be concluded that as of September 2022, there already existed an extensive network of psychological services in higher education institutions across the Russian Federation, comprising at least 402 units. Psychological services were represented in universities across all federal districts of the country.

Among universities that did not have a psychological service at the time of the study, 38,9% reported plans to establish one in the near future. Such plans were significantly more common among main university campuses than among their branch campuses (53,1% vs. 12%; χ² = 11,71; p ≤ 0,01).

Organizational context

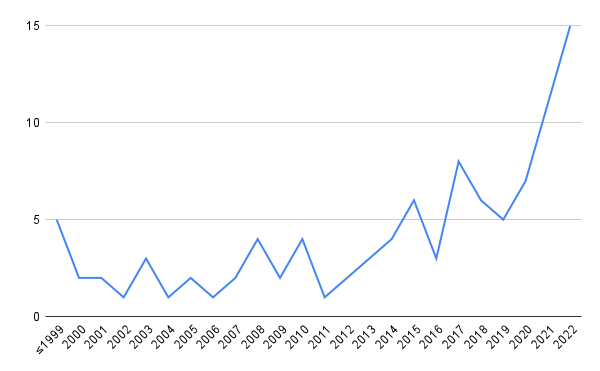

The establishment of a system of university psychological services in Russia began in the 20th century (see Fig. 1). Currently, 5% of existing university psychological services were founded before 1999. Approximately 27,7% of the services have been operating for more than ten years. At the same time, there has been a marked increase in the number of newly established services in recent years: 35,8% of all university psychological services in the country were created within the five years preceding the study, and 24,6% were founded in 2021 or during the first half of 2022.

Certain characteristics of universities are associated with a higher likelihood of having a psychological service. Specifically, public universities are more likely than private ones to have such a service (86% vs. 70,9%; χ² = 8,33; p ≤ 0,05), and inclusion in competitive grant programs or national rankings increases this probability (91% vs. 82,1%; χ² = 4,7; p ≤ 0,05). Conversely, branch campuses are significantly less likely to have a psychological service compared to main university campuses (45,7% vs. 88,6%; χ² = 58,21; p ≤ 0,01).

Models of organization of psychological services

University psychological services in Russia operate under various organizational models. In most cases (51%), the staff psychologists are directly employed within the psychological service itself. Somewhat less frequently (42,8%), the service is staffed by university employees who combine this work with other positions. Only in 5% of cases are the psychologists external specialists whose work is compensated based on the volume of services provided, and in 2,2% of cases the entire service is fully outsourced.

Psychological services also differ in their formal institutional structure. In one-quarter of cases (25,1%), the service is established as an independent structural unit. In 8% of cases, it functions as part of a broader institutional entity—such as a university’s psychological, medical, and social service. However, every second service (51,5%) is organized in another form: for example, psychological services may be included within various university faculties or departments, youth and social policy offices, student affairs units, or university health centers. In 14,2% of cases, the psychological service has no formal institutional status, although its functions are still being performed within the university.

Activities of the services

All university psychological services are primarily focused on providing psychological assistance to students. Support for other potential recipient groups is offered much less frequently: parents or legal guardians of students — 60,2%; university administration — 51,5%; auxiliary staff — 43,5%; university alumni — 21,4%; and individuals with no affiliation to the university — 6,7%.

Most psychological services offer assistance in multiple formats. Individual counseling is provided in nearly all services (99%), while group formats are also widely available (91%). Offline support is more prevalent than online (93,8% and 81,6%, respectively), and 78% of services operate in both formats simultaneously.

The majority of services focus on short-term psychological counseling (1–3 sessions) (89,6%) or crisis intervention (80,3%). Medium-term counseling (4–10 sessions) is available in more than half of the services (64,2%), whereas long-term counseling (more than 10 sessions) is offered in only about one-third (38,8%). At the same time, most services (88,1%) have no official limit on the number of sessions per client. Psychological assistance is predominantly provided in Russian (98,8%); 13,2% of services can provide support in English, and only 4,5% offer assistance in other languages.

As a rule, university psychological services implement between one and ten main areas of activity (see Table 1)

Table 1

Directions of work of psychological services of higher education institutions, n, %

|

Directions of work |

% |

Number of universities |

|

Psychological counseling |

97,8 |

393 |

|

Conducting awareness-raising training activities with students |

94,3 |

379 |

|

Psychological diagnostics |

91,3 |

367 |

|

Psychological monitoring and identification of risk groups |

86,1 |

346 |

|

Conducting educational training events with university employees |

70,1 |

282 |

|

Participation in the university development program |

64,4 |

259 |

|

Participation in the design and expertise of university programs and projects |

55,5 |

223 |

|

Maintaining social media publics for psychological education purposes |

52,0 |

209 |

|

Helpline |

35,6 |

143 |

|

Creating chatbots |

10,4 |

42 |

Services formally established as independent structural units within universities are significantly more likely to carry out a larger number of activity areas (7–10) compared to services without formal institutional status (χ² = 6,67; p ≤ 0,01). The dominant form of work across services is psychological counseling. At the same time, among the wide range of reasons students seek psychological assistance, clinical symptomatology prevails (see Table 2).

Table 2

Dominant subjects of applications to the psychological service, n, %*

|

Dominant subjects of references |

% |

Number of universities |

|

Relieving a painful symptom |

63,7 |

146 |

|

Normalization of interpersonal relations with students, classmates |

37,1 |

149 |

|

Solving problems in relationships with parents |

36,8 |

148 |

|

Assistance in self-development |

34,1 |

137 |

|

Academic failures and issues related to university studies |

33,3 |

134 |

|

Normalizing interpersonal relationships with a romantic partner |

31,6 |

127 |

|

Help in adapting to living away from home and parents |

17,9 |

72 |

|

Normalization of interpersonal relations with teachers |

9,7 |

39 |

|

Help in planning for the future |

8,5 |

34 |

|

Help with self-discovery |

8,5 |

34 |

|

Other |

3,2 |

13 |

Note: «*» – respondents could choose no more than three answer options.

Both underload and overload of psychological services are observed. Underload is characteristic of 12,9% of institutions, primarily those in which the services were established recently (χ² = 6,46; p ≤ 0,05) and in university branch campuses (41,2% vs. 12,2%; χ² = 11,71; p ≤ 0,001). Overload, on the other hand, is reported by every third psychological service (33,9%). This situation is more typical for universities participating in the “Top 5-100” program (73,3% vs. 32,2%; χ² = 10,86; p ≤ 0,01), for public universities (36,2% vs. 11,4%; χ² = 8,7; p ≤ 0,01), for services that serve as practicum bases for psychology students (41,4% vs. 28,7%; χ² = 6,65; p ≤ 0,01), and overall for more developed services with a larger number of staff members (χ² = 10,54; p ≤ 0,05).

In addition to their core psychological functions, university administrations often assign psychological services other types of tasks. The majority of services (72,7%) report receiving assignments from university leadership related to educational and character-building activities, while 43% indicate that they were tasked with conducting informational or preventive campaigns aimed at discouraging students from participating in unauthorized public actions.

Staff composition

The median number of employees in the surveyed psychological services was two (min = 1, max = 40). Approximately one-third of services employ only one staff member (35,8%), and another third have 2–3 employees (34,8%). In most cases, services have no more than six staff members (88,8%). The workforce of psychological services is predominantly female: only 19,2% of the surveyed services reported having a male psychologist on staff.

Universities set varying requirements for the professional qualifications of psychological service employees. While work experience requirements are often not specified (43,3%), in more than half of the cases (61,2%) staff members are required to undertake professional development at least once every three years, and in 16,2% of cases, annually. Professional development may be funded by the university or organized internally. In half of the cases (48,0%), universities pay for employees’ continuing education in external organizations, and in one-quarter of cases (25,1%) they offer such training internally. Additionally, 16,2% of services organize supervision sessions, and 14,7% hold intervision meetings.

Personal therapy is required for staff members in only 6,5% of cases, with this requirement being more common in public universities (χ² = 7,04; p ≤ 0,01).

Many services lack sufficient staffing diversity, particularly in terms of specialists with different areas of expertise. Specifically, only one-third of services (33,1%) employ at least one counseling psychologist with a clinical or medical psychology specialization. Considering the predominance of quasi-clinical issues among student requests, the absence of such specialists may negatively affect the overall effectiveness of the service.

Formalized cooperation with external mental health services (psychological or psychiatric) exists in only about one-third of universities (30,6%), while in 43,8% of cases such collaboration relies on personal contacts between staff members—an approach that may be vulnerable in the long term.

Material and technical resources

In 52,3% of cases, the facilities allocated to psychological services are considered insufficient for effective work by their staff, and 11,9% of service psychologists do not have their own designated workspace (desk/chair). The premises of every third service (39,3%) are reported to require renovation.

Evaluation and communication of psychological service outcomes

Only about half of the services (56%) conduct an evaluation of their effectiveness. In one-third of cases, effectiveness is assessed through client feedback (31,3%), and equally often through pre–post outcome measures (35,6%). Evaluation of service effectiveness is more common in universities where the service has existed for a longer period (χ² = 7,08; p ≤ 0,05), employs a larger number of staff members (χ² = 22,41; p ≤ 0,01), and is formally established as an independent structural unit (77,3% vs. 55,2%; χ² = 14,7; p ≤ 0,01).

Unique information about student or staff issues obtained through the work of psychological services is rarely used for further institutional analysis. Most often, such information is discussed internally within the service during intervision sessions or planning meetings (38,3%), and in one-third of cases (34%) it is submitted as an analytical report to university leadership or staff. Only in 15,4% of cases is this information officially discussed during meetings with university administration, and in just 10,2% of cases it is shared during meetings with other university departments.

Discussion

The conducted study demonstrates that the presence of psychological services in universities is a highly prevalent practice. As of 2022, an extensive network of university psychological services was already operating across the Russian Federation, comprising at least 402 units. Such services exist in universities of all federal districts, under various ministerial jurisdictions, and of different sizes.

Although the history of university psychological services in Russia spans more than 25 years, their most rapid expansion has occurred in recent years. Moreover, more than one-third of universities that did not yet have such services at the time of the study reported plans to establish them in the near future (38,9%). This makes it especially important to clarify what is actually meant by the statement “a psychological service operates within a university.”

Based on the obtained data, it is appropriate to speak of a high degree of variability among psychological services in Russian universities. Several developmental stages of psychological services can be identified. The initial, or “zero,” stage is characterized by the absence of formal institutionalization: the service is not officially established, and its functions—typically very limited—are performed by a single psychologist. Approximately one-third of all psychological services (35,8%) were at this initial stage at the time of the study. A developed psychological service, by contrast, is characterized by the presence of multiple psychologists and administrative staff. Such a service is typically established as an independent structural unit, performs a broad range of tasks (including analytical activities), and conducts evaluations of its own effectiveness. Another basis for classification may be the degree of integration between the psychological service and other university functions. At one pole is the hybrid model, in which the psychological service is closely integrated with educational activities and also serves as a practicum base for psychology students (33,8%). At the opposite pole is the outsourced model (2,2%), which may operate largely autonomously from the university. This classification broadly aligns with the typology proposed by I.V. Makarova (Makarova, 2017), but introduces two distinct dimensions for subgroup differentiation: (1) the level of service development (from initial to advanced) and (2) the level of integration with educational activities. At the current stage of development of psychological services, identifying clearly distinct types of functioning appears to be difficult; therefore, a dimensional rather than typological approach to describing their variability seems more appropriate.

The diversity of organizational formats among psychological services is matched by the diversity of their activities and available resources. Although the dominant function of these services is providing psychological assistance to university students—often accompanied by psychoeducational interventions and psychological assessment—other functions and the capacity to implement them vary considerably. Therefore, any evaluation of the effectiveness of psychological services should take into account both their organizational format and the resources available to them.

It is important to note that the resources and level of development of psychological services are often associated with the characteristics of the universities themselves. Institutions that have succeeded in competitive federal support programs and possess more advanced scientific and educational infrastructures (those participating in the Priority 2030 and/or Top 5-100 programs), as well as main university campuses, are not only more likely to establish psychological services but also to do so on a larger scale. Similar trends were previously observed in analyses of university psychological service websites (Gaete et al., 2024). Indicators such as the establishment of a service as an independent structural unit and the larger number of staff members are also more common in more developed services with broader functional profiles. At the same time, the mere duration of a psychological service’s existence does not serve as a significant predictor of its size or range of activities.

Conclusion

This study represents the first step toward a comprehensive understanding of the current state of psychological assistance within the higher education system of the Russian Federation. It has made it possible to quantitatively assess the key characteristics of how psychological support functions in Russian universities.

The obtained data indicate that Russia has already accumulated substantial experience in operating university psychological services, while also revealing systemic limitations in their functioning. Priority areas for further development include strengthening material and human resources, as well as expanding opportunities for professional development and training of staff. Given the high prevalence of clinically oriented requests, another strategically important task is to ensure effective collaboration between university psychological services and the psychiatric care system, as well as with other related institutions and agencies.

It is essential to foster a consistent understanding among university leadership regarding which functions a psychological service should or can perform, and which fall outside its professional scope. There are concerning instances in which university administrations assign educational or supervisory functions to psychological services. Such practices may have potentially negative consequences for the development of these services and may undermine students’ trust in university psychological support systems.

At the time of the study, most university psychological services focused primarily on students as their main target group for support and intervention. Providing services for university staff—an approach envisioned by the Concept for the Development of Psychological Services (Gaete et al., 2024)—was implemented in a substantially smaller share of services. The accumulation and dissemination of effective practices already developed for working with university employees are therefore crucial for the further advancement of this area.

As several national projects and initiatives aimed at improving the system of university psychological services have been launched in Russia over the past few years, the data presented in this article may serve as a baseline for assessing future progress and trends in their development. Another promising avenue for further research involves studying the factors that influence the effectiveness of psychological services. What resources are essential for their successful operation? Which organizational models are most effective for universities of different types? And how can their effectiveness be objectively evaluated? These questions remain open and warrant continued investigation.

Limitations. The obtained data may potentially be biased due to several factors. First, self-selection bias is likely–universities with psychological services and/or those with more developed psychological services may have been more likely to participate in the study. Additionally, data quality may have been suboptimal in cases where the university-level documentation of the service's activities was insufficient, and the responsible staff lacked complete information about its functioning.