Introduction

The concept of ethnic identity

The search for answers to the question: “Who am I?”, the search for ethnic identity by an individual, a social group, a society is a relevant point in modern scientific psychology. E. Erikson defined identity as an important condition for maintaining an individual’s mental health, authenticity, stability and internal integrity. In modern psychological science, the individual’s need for ethnic identity is formed much more broadly than just belonging to a certain group or social community [Brass, 2023]. The need for identity is also determined by the individual’s understanding of the historical experience of the ethnic group, which actualizes the fundamental nature of scientific research into this problem [Erikson, 1968].

According to C. Cooley, identity is associated with the notion of the Self-concept and the subjective reflection of the opinions of others. Personality is formed within the process of interaction with society, i.e. identity is part of the Self-concept, which is responsible for the awareness of one’s group affiliation. That said, identity is an area of self-awareness and formed by a generalization of the opinions of people around a person [Colley, 1994]. R. Fogelson believed that a struggle between four types of identity occurs within a person: real identity, ideal identity, negative identity and presented identity. In the struggle of identities a person strives to bring real identity closer to the ideal one and to reduce the distance between real and negative identities [Fogelson, 1982].

In Russian psychology, identity was mainly studied within the framework of self-awareness, self-determination and socialization of the individual. This topic was investigated by L.S. Vygotsky, A.N. Leontiev, L.B. Schneider, T.G. Stefanenko and others [Vygotskii, 1983; Stefanenko, 2009; Shneider, 2022]. The notion of self-awareness in Soviet psychology was first studied by L.S. Vygotsky. He viewed self-awareness as a higher form of consciousness, which is facilitated by the development of speech, voluntary movements and the growth of independence [Vygotskii, 1983]. V.V. Stolin viewed identity as self-awareness of the individual, which has a multifaceted structure [Stolin, 1983]. I.S. Kon investigated identity within the framework of the problem of the “Self” and the “Self- Image”. “Self” implies the presence of information about oneself and the continuity of mental activity, and the “Self-Image” corrects it, i.e. the “Self-Image” is a set of an individual’s ideas about himself [Kon, 1984].

Human nature is structured in such a way that an individual constantly identifies himself with a certain group with which he has connections, or which is close to him in its ideology, value system, system of views [Berberyan, 2019a]. In psychological sense, it is important to understand that identification is associated with basic human needs. This strengthens the sense of self-preservation, self-affirmation, self-expression. Thus, a person needs to feel his belonging to society, a reference group, and much more [Dyurkgeim, 1991].

Ethnic identity is a part of social identity, which implies awareness of one’s belonging to a certain ethnic community. Ethnic identity includes a cognitive component, i.e. an idea of the characteristics of one’s group, awareness of oneself as a member of it, and an affective component — the significance of membership in this group, attitude to its qualities and their assessment. The attitude towards one’s own ethnic community is expressed in ethnic attitudes [Abrams, 2006; Umaña-Taylor, 2011]. Participation in the social life of an ethnic group is often considered as an indicator of ethnic identity. However, the question of the stability of the connection between who a person considers himself to be and how he acts in real life is still being considered [Fishman, 2010]. In traditional societies, participation in the social life and culture of an ethnic group is a necessary condition for the formation of ethnic identity [Phinney, 2007].

The concept of time in psychology

The problem of psychological time, the temporality of personality is substantiated in the works of P. Janet, Ch. Buhler, K. Levin, S.L. Rubinstein, B.G. Ananyev, K.A. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya, T.N. Berezina, E.I. Golovakha, A.A. Kronik, S.B. Nesterova, F. Zimbardo, J. Boyd, V.I. Kovalev and others. The results of empirical studies related to the attitude towards time were presented by S.V. Dukhnovsky, E.V. Zabelina, Ya.V. Kravtsova, T.D. Dubovitskaya, D.L. Prokopyev, P.I. Yanichev and others.

The main directions of research on time in psychology are associated with the concepts of human ontogenesis as a unity of the biological, social and subjective [Golovakha, 2008]. In scientific psychology, the temporal characteristics of a person as an individual, as a personality and as a subject are considered at four main levels: 1) psychophysical, 2) psychophysiological, 3) social and psychological and 4) personal and psychological. Along with this, three approaches to the study of time are considered: situational, biographical and historical.

- The psychophysical level involves identifying the parameters of physical time, such as topological (simultaneity, sequence) and metric (duration) characteristics, and the unconscious mechanisms of their mental reflection. The psychophysical level is manifested in the form of directly experienced and assessed time [Nestik, 2003]. S.Ya. Rubinstein also identified subtypes of time perception: a direct sense of duration and a subjective perception of time [Rubinstein, 1976]. W. Wundt pioneered in conducting an experimental study and revealing the subjective perception of objectively given time intervals of the same duration [Cristalli, 2022].

- The psychophysiological level reveals the psychophysiological mechanisms of time perception, human adaptation to the dynamics of mental processes depending on biological rhythms and the organization of biological time. For the first time, I.M. Sechenov drew attention to the fact that the perception of time occurs due to several “sensitive devices” [Rumyantseva, 2018]. Treisman and other researchers revealed the relationship between the perception of time and the coordination of the motor act, experimentally proving that it is the work of the so-called “internal clock” and its frequency that ensure the perception of time in humans [Shipp, 2009]. At the psychophysiological level, when studying the time phenomenon, the neurons were detected that respond to a specific time interval [O'Neill, 1979]. These results correlate with the theory associated with the time analyzer proposed by E.N. Sokolov [Sokolov, 2004].

- The social and psychological level reveals the features of a person’s perception of “social” time in the context of social and cultural conditions, especially human ontogenesis, social generation, and the history of society. From the perspective of this triad, the time of an individual, genera tion, and history is considered. Within the framework of this level, the most profound study of three spheres was observed: organizational, economic, and cross-cultural psychology. In the context of our research, a studies on the ethnocultural characteristics of time perspective and time orientation (Jones, Syrtsova and others), group ideas about the sources of time are of particular interest [Block, 1996].

- Psychological (personal) level. The psychological content of the category of time is most fully manifested in the concept of “psychological time”. E.I. Golovakha and A.A. Kronik note the significant role of higher mental functions, a conscious attitude to the past, present and future and their assessment, the formation of a holistic idea of time in general in the processes of experiencing long periods of time [Golovakha, 2008]. Pierre Janet pioneered in investigating the concept of the life path of an individual. He correlated time phases with biographical stages of a person’s life path, linking together biological, psychological and historical time in the structure of the ethnogenesis of an individual.

In psychological research, when studying the mechanisms of time perception, the “event concept of psychological time” becomes traditional; in this concept, the indicators of time perception — its speed, saturation, duration — directly depend on the number and intensity of life events. However, the event concept, which focuses on the change in thoughts, feelings, actions, and human behavior when perceiving time, does not allow to resolve issues related to the definition of boundaries and interrelationships of the present, past, and future, subjective assessment of time, and mechanisms for time perception formation [Golovakha, 2008].

The concept of time in existentialism and the connection with ethnic identity

Special attention is paid to the features of psychological time in cross-cultural psychology [Nestik, 2003]. One of the phenomena that associated with psychological time is identity. As researchers acknowledge, it is psychological time and the ability to store information about the past that contribute to the process of identity formation and development. The scientific literature reflects the results of empirical studies indicating that the processes of identity development and the development of time perspective mutually reinforce each other [Luyckx, 2010].

The period of emerging adulthood, when a person strives to link together his past, present and future, integrating them into a single process and at the same time building connections between the events of his own life, has been particularly broadly investigated [Nestik, 2003; Rubinstein, 1976; Luyckx, 2010]. In some approaches, the temporal aspects of identity are considered as multiple cognitive components of the self-concept, existing in the temporal dimension of identity: in the past, present (actual), prospective, future [Heidegger, 2002; Shipp, 2009; Treisman, 1992]. Empirical studies have confirmed the hypothesis that identity is connected with ideas about one’s Self in the process of event saturation of the past, present and future. Identifying the attitude towards the temporary stages of an individual’s life is an indicator of the level of self-identity formation [Rubinstein, 1976; Abrams, 2006; Luyckx, 2010].

Studies of phenomena associated with the experience of time have revealed cultural and individual values that act as predictors of psychological time. The perception of time in different cultures has a special, specific character. Armenia is one of the countries whose population has an axiological thinking, and the category of time is expressed clearly and consciously. In this perspective, a study of psychological time among representatives of Armenia will allow us to identify the features of the psychological time and its components, compare the indicators of psychological time, and determine the components of the structure of psychological time.

Relevance. In modern society, a person learns about himself, the history of his country and, ultimately, his identity through determining his place in actual reality. Knowledge of the past together with the knowledge of the present allow a person to build the future. The relevance of this study is that personal identity acts as the most important characteristic of the phenomenon of social integrity and uniqueness; identity is a reflection of the inseparable unity of three time projections: past, present and future.

The goal of the study is the investigation of the features of identity and the subjective assessment of the time of the personality in a psychological perspective.

Research hypotheses. We assume that there is a relationship:

- between the feeling of being an Armenian and the length of residence in Armenia.

- between feelings towards one’s people and the length of residence in Armenia.

- between the subjective assessment of time and the feeling of being an Armenian.

Methods

The methodological basis of the study — the theories and conceptual provisions of E. Erikson, J.G. Mead, C. Cooley, R. Fogelson, I. Goffman, L. Vygotsky, A. Leontiev, L. Schneider, T. Stefanenko and others.

Research participants. We conducted a study with ethnic Armenians, students of the Russian-Armenian University and the Yerevan branch of the Plekhanov Russian University of Economics (Yerevan, Armenia), a total of 89 people. The average age of the participants was 19.6 years (SD = 1.3), representatives of both sexes (male —

14.6%, female — 85.4%), undergraduate students. Confidentiality and anonymity were complied with in the study.

Research methods. We conducted empirical study using the following methods.

- Author’s questionnaire. This questionnaire included 7 questions aimed at identifying social and demographic data. The questionnaire results revealed the participants’ age and sex, length of residence in Armenia, course of study and professional orientation.

- Assessment of the severity of ethnic identity (N.M. Lebedeva). This scale reveals the severity of ethnic identity by assessing the feeling of belonging to one’s nationality on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 is “I do not feel at all” and 5 is “I feel fully” [Tatarko, 2011].

- Scale for express evaluation of feelings associated with ethnicity (N.M. Lebedeva). This scale reveals the strength of feelings associated with ethnic identity, using a scale from 1 to 5 [Tatarko, 2011].

- The questionnaire “Types of ethnic identity of a personality” (G.U. Soldatova, S.V. Ryzhova). This technique reveals the intensity of different types of ethnic identity: ethno-nihilism, ethnic indifference, positive ethnic identity, ethno-egoism, ethno-isolationism and ethno-fanaticism. The participant is asked to rate the answers to 30 judgments “I am a person who ...” from 0 to 4 [Soldatova, 1998].

- Semantic time differential (SDT; L.I. Wasserman and others). This technique reveals the perception of individual psychological time. The SDT technique involves assessing 25 polar properties, the expression of which should be assessed from 1 to 3. The participant is asked to assess these properties separately for three tenses: present, past and future [Vasserman, 2005].

Data analysis. Statistical data analysis was performed through writing code in R (R Development Core team, 2021). The nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test (function kruskal_test in rstatix), Dunn’s post hoc test (function dunn_test in rstatix) and Pearson’s chi-square test (function chisq.test in R) were used to test the hypotheses. The entire analysis code along with anonymized data can be found on the OSF page of this project: https://osf.io/efhwj/

Results

Descriptive statistics

Based on the results of the author’s questionnaire, the main socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents were identified, which are presented in Table. 1.

Empirical testing of hypothetical assumptions

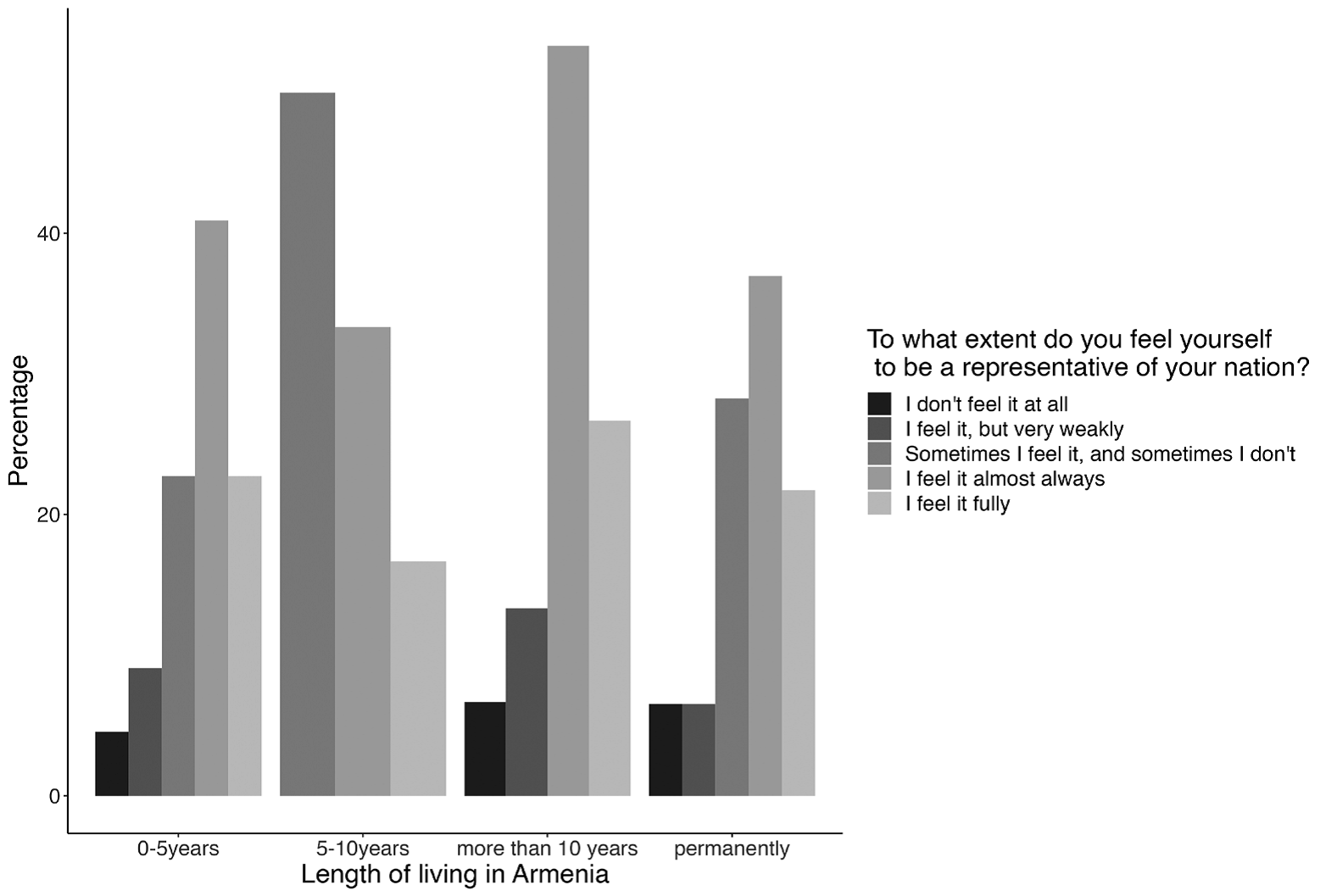

Analysis of the relationship between feeling like an Armenian and the length of residence in Armenia. To the question: “To what extent do you feel like a representative of your nation?” the following answers were received: 5.6% of respondents answered: “I don’t feel it at all”, 7.9% of participants answered: “I feel it, but very weakly”, 23.6% of participants answered: “Sometimes I feel it, and sometimes I don’t”, 40.4% of participants an

Table 1 Descriptive statistics

|

Participants |

Quantity |

Percentage |

|

Year of study |

||

|

1 |

36 |

40,4% |

|

2 |

24 |

26,9% |

|

3 |

20 |

22,4% |

|

4 |

9 |

10, 3% |

|

Sex |

||

|

Female |

76 |

85,4% |

|

Male |

13 |

14,6% |

|

Duration of residence in Armenia |

||

|

0—5 years |

22 |

24,7% |

|

5—10 years |

6 |

6,7% |

|

more than 10 years (with breaks) |

15 |

16,9% |

|

permanently |

46 |

51,7% |

|

Field of study |

||

|

STEM |

11 |

12,4% |

|

Humanities |

18 |

20,2% |

|

Social sciences |

60 |

67,4% |

|

Age range |

||

|

18—20 years |

68 |

76,4% |

|

20—24 years |

21 |

23,6% |

|

Total number of participants |

89 |

100% |

swered: “I feel it almost always”, while 22.5% of participants answered: “I feel it fully”. To test the hypothesis about the presence of a connection between feeling an Armenian and the length of residence in Armenia, the results of this scale were visualized for 4 groups of participants. These results are presented in Fig. 1. The use of the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test revealed the absence of statistically significant relationships between the results of the four groups (p = 0.8299).

Analysis of the relationship between feelings towards one’s nation and the length of residence in Armenia. Based on the answers to the question: “What feelings does belonging to your nation evoke in you?”, the following answers were received: 28.1% of participants answered “Pride”, 29.2% of participants indicated “Calm confidence”, 33.7% of participants answered “No feelings”, 2.3% of participants answered “Resentment”, 6.7% of participants answered “Infringement, humiliation”. To

test the hypothesis about the presence of a relationship between feelings towards one’s nation and the length of residence in Armenia, the results were visualized (Fig. 2). Using the Kruskal-Wallis criterion and the paired Dunn’s post hoc test (Table 2), statistically significant relationships were revealed between feelings towards one’s nationality only for two groups: those living in Armenia from 0 to 5 years and the ones living more than 10 years, with interruptions (p = 0.0376). Participants living in Armenia for up to 5 years were characterized by an average rating of 2.68, between the scale values: 2 and 3, where 2 represents calm confidence and 3 — no feelings. Participants living in Armenia for more than 10 years with breaks were characterized by a lower average rating of 1.87, between the scale values: 1 and 2, where 1 represents pride and 2 — calm confidence.

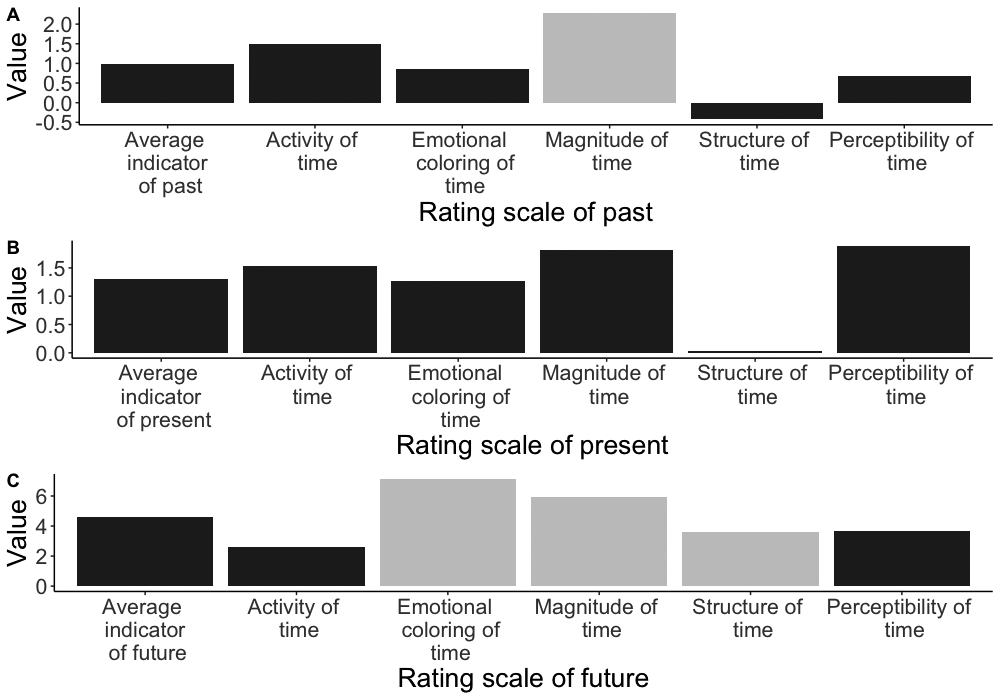

Analysis of the relationship between the assessment of time perception and the feeling of being an Armenian. Semantic time differential technique was used to assess the subjective perception of individual psychological time. Based on the results of this technique, average values were identified for 5 scales, as well as average values for each of the times (Table 3). The obtained average values were compared with the normative values for each of the scales and times and allocated to a high or low level (Fig. 3). Average values for all scales of the present time belong to a reduced level. The average value of the past time on the “Magnitude of time” scale corresponds to an increased level compared to the normative values. For the future time, average values are observed on three scales at once: “Emotional coloring of time”, “Magnitude of time” and “Time Structure” — and correspond to an increased level compared to the normative values.

Using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test and the paired Dunn’s post hoc test, statistically significant relationships were found between the results of feeling an Armenian and the results of the past and future. No statistically significant differences were found between the results of feeling an Armenian and the results of the present (p = 0.446). Statistically significant results are presented in Table 4 (for the past) and Table 5 (for the future).

Results of the study of types of ethnic identity

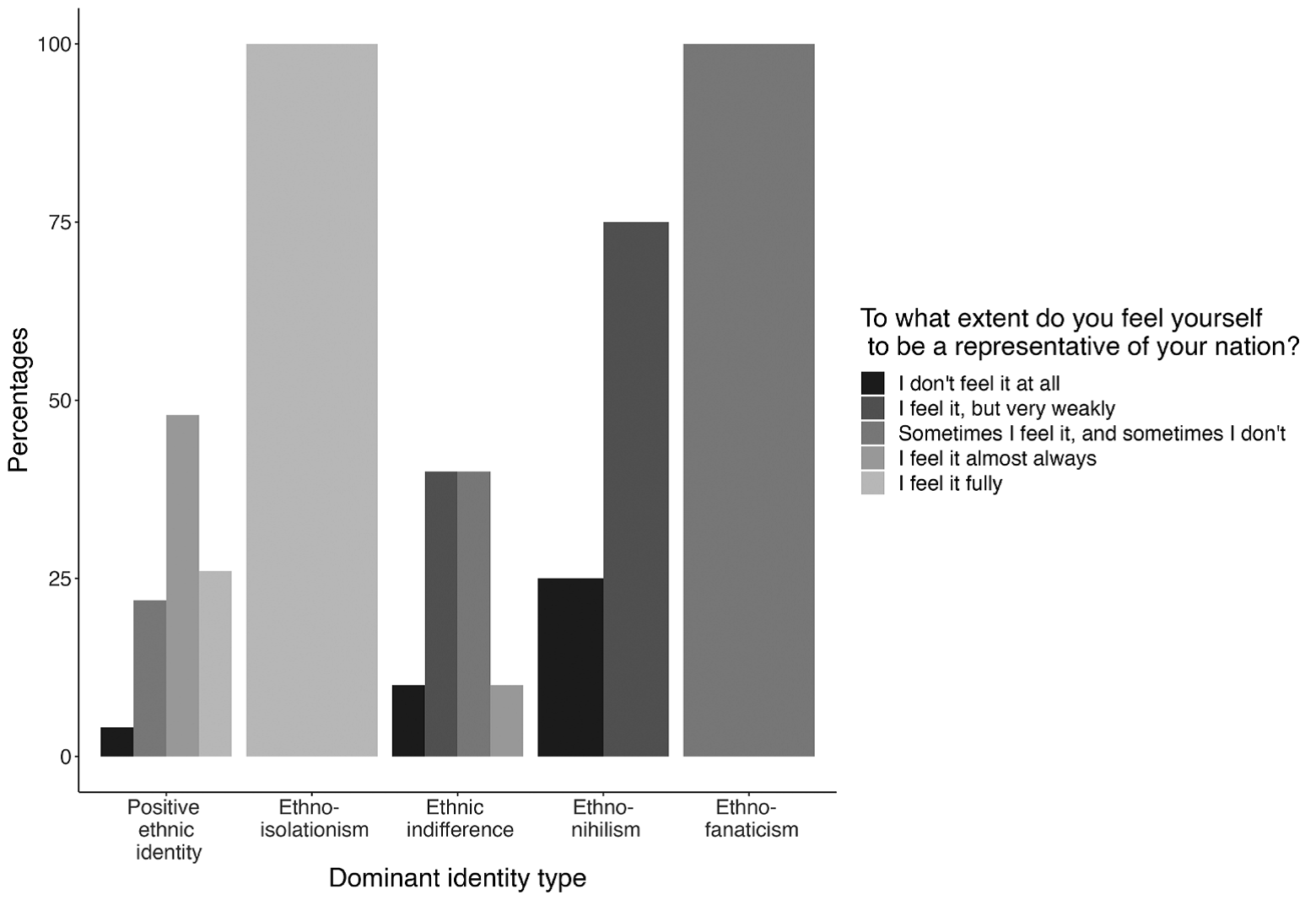

Analysis of the relationship between types of ethnic identity and the feeling of being an Armenian. According to the results of the study, values were identified for each of the 6 types of ethnic identity, as well as the dominant type of ethnic identity for each of the participants. Most participants (82.2%) had a positive ethnic identity as the predominant type of identity (Table 6).

By using the Pearson’s chi-square test, a relationship was found between the type of ethnic identity and the feeling of being an Armenian (Chi-square = 62.45, df = 16, p-value < 0.001). To assess the strength of this relationship, we calculated Cramer’s V, which yielded a high association value (V = 0.42). The predominant group, with a positive ethnic identity, was characterized by values for four different feelings: 50% feel Armenian almost always, 26% feel Armenian fully, 21.9% sometimes feel Armenian, and only 4.1% do not feel Armenian at all (Figure 4).

Table 5. Results of Dunn’s paired post hoc test for analyzing future assessment depending on feeling an Armenian

|

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

Statistic values |

P-values |

|

I don’t feel it at all |

I feel it, but very weakly |

—2,33 |

0,02* |

|

I don’t feel it at all |

I feel it almost always |

—1,81 |

0,07. |

|

I feel it, but very weakly |

Sometimes I feel it, sometimes I don’t |

2,58 |

0,009** |

|

I feel it, but very weakly |

I feel it fully |

2,06 |

0,04* |

|

Sometimes I feel it, sometimes I don’t |

I feel it almost always |

—2,27 |

0,023* |

Table 2. Results of Dunn’s paired post hoc test for analyzing feelings towards one’s nationality depending on the length of residence in Armenia

|

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

Statistic values |

P-values |

|

0—5 years |

5—10 years |

–0,510 |

0,610 |

|

0—5 years |

More than 10 years, with breaks |

–2,08 |

0,0376* |

|

0—5 years |

Permanently |

–1,46 |

0,143 |

|

5—10 years |

More than 10 years, with breaks |

–0,955 |

0,339 |

|

5—10 years |

Permanently |

–0,333 |

0,739 |

|

More than 10 years, with breaks |

Permanently |

1,07 |

0,287 |

Table 3. Results of Semantic time differential

|

Scale |

Past |

Present |

Future |

|||||||||

|

M |

SE |

M |

SE |

M |

SE |

|

||||||

|

Activity of time |

1,49 |

0,51 |

1,53 |

0,5 |

2,57 |

0,44 |

||||||

|

Emotional coloring of time |

0,85 |

0,77 |

1,27 |

0,75 |

7,11 |

0,7 |

||||||

|

Magnitude of time |

2,29 |

0,61 |

1,81 |

0,57 |

5,91 |

0,71 |

||||||

|

Structure of time |

–0,43 |

0,57 |

0,03 |

0,45 |

3,62 |

0,57 |

||||||

|

Perceptibility of time |

0,69 |

0,5 |

1,89 |

0,54 |

3,66 |

0,56 |

||||||

|

Average time assessment |

0,98 |

0,46 |

1,31 |

0,44 |

4,58 |

0,5 |

||||||

Table 4

Results of Dunn’s paired post hoc test for analyzing future assessment depending on feeling an Armenian

|

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

Statistic values |

P-values |

|

I don’t feel it at all |

Sometimes I feel it, sometimes I don’t |

2,30 |

0,02* |

|

I don’t feel it at all |

I feel it almost always |

2,54 |

0,01* |

|

I don’t feel it at all |

I feel it fully |

3,08 |

0,002** |

|

I feel it, but very weakly |

I feel it fully |

1,98 |

0,04* |

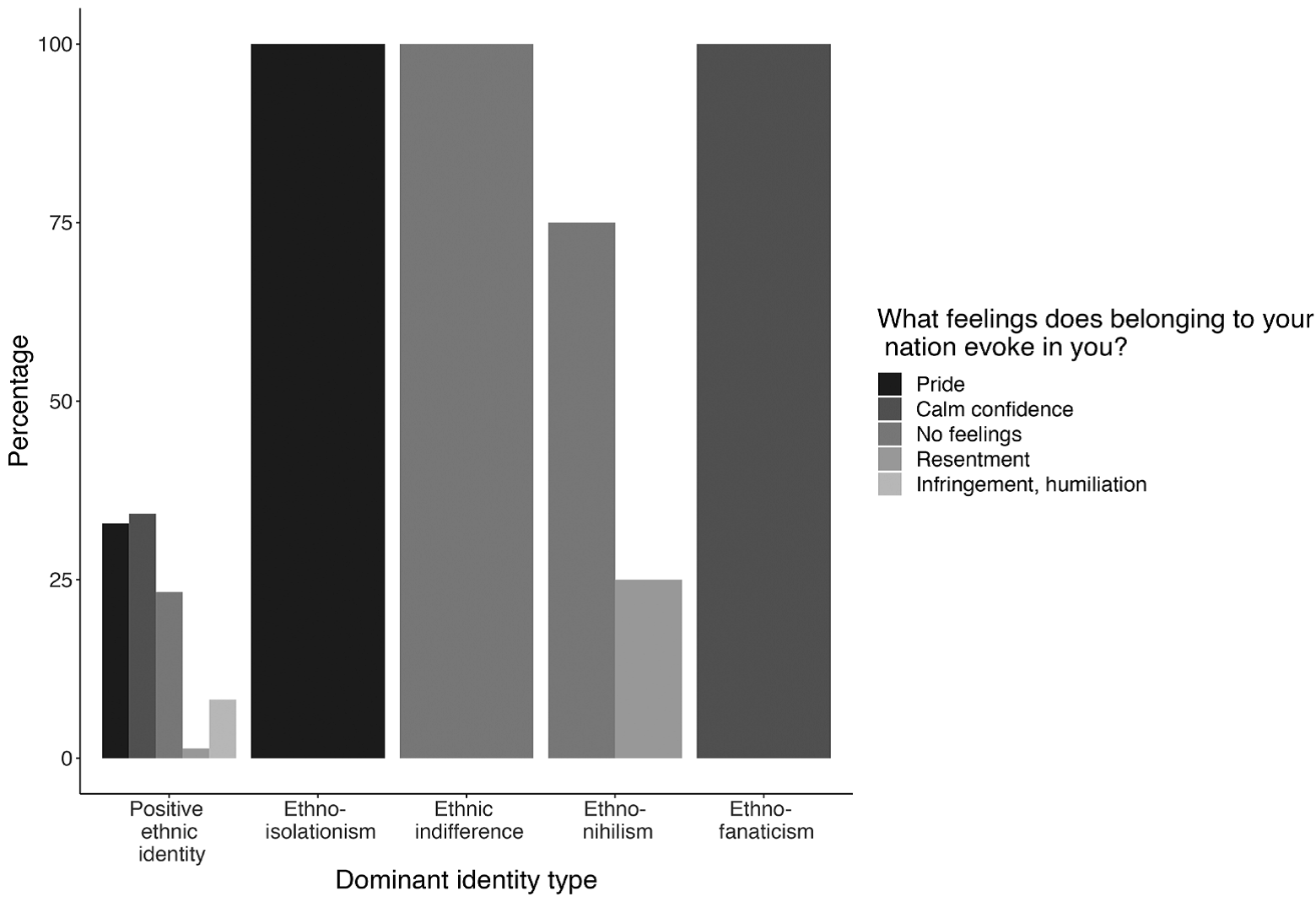

Analysis of the relationship between the types of ethnic identity and feelings towards one’s nation. Using the Pearson’s chi-square test, the existence of a relationship between the type of ethnic identity and feelings towards one’s nationality was revealed (Chi-square = 42.51, df = 16, p-value < 0.001). To assess the strength of this relationship, we calculated Cramer’s V, which resulted in a moderate association value (V = 0.35). The group with a positive ethnic identity was characterized by values for all five feelings, where most participants felt calm confidence (34.2%) and pride (32.9%), followed by 23.3% having no feelings, 8.2% — infringement, and 1.4% — resentment (Fig. 5).

Table 6

Predominant type of ethnic identity among participants

|

Predominant type of identity |

Quantity of participants |

Percentage of participants |

|

Positive ethnic identity |

73 |

82,02 % |

|

Ethno-fanaticism |

1 |

1,12% |

|

Ethnic indifference |

10 |

11,24% |

|

Ethno-nihilism |

4 |

4,50% |

|

Ethno-isolationism |

1 |

1,12% |

|

Ethno-egoism |

0 |

0% |

|

Total |

89 |

100% |

Fig. 5. Feelings associated with belonging to one’s nation in participants with different types of ethnic identity

Discussion

This study was conducted to identify the features of ethnic identity and subjective perception of time depending on social and demographic characteristics. The study was conducted with ethnic Armenians, students of various fields and levels of professional training. Based on the results of the assessment of the expression of ethnic identity, it was found that the majority of participants felt themselves to be representatives of their nationality “almost always”. These results are consistent with the results of previous studies [Berberyan, 2019; Berberyan, 2014].

The hypothesis about the relationship between individual perception of time and the feeling of being an Armenian was confirmed. Based on the results of the assessment of time perception, high average results were found on the “Magnitude of time” scale for the past and future. This relationship shows a high semantic fulfillment of time, a sense of freedom.

The hypothesis about the relationship between the dominant types of ethnic identity and feelings towards one’s people was also confirmed. Most participants with a positive ethnic identity were characterized by feelings of calm confidence (34.2%) and pride (32.9%). Participants with ethnoi-solationism were characterized with only pride out of all possible choices. Participants with ethnic indifference had only values on one scale — “No feelings”. Most participants with ethno-nihilism (75%) had values on the “No feelings” scale, the remaining 25% — on the “Resentment” scale. Participants with ethno-fanaticism were characterized by values on only one scale — “Calm confidence”. It is important to note that the connections in the groups of participants were not equally represented. Thus, the results of assessing feelings towards their nationality differed in two groups: 1) among Armenians living in Armenia from 0 to 5 years, and 2) among Armenians living in Armenia for more than 10 years — with breaks with slightly higher values in the first group.

Additionally, a link was found between the feeling of being an Armenian and the results of assessing the past and the future. This link, according to the high average indicators obtained on the “Emotional coloring of the future tense” scale, characterizes satisfaction with the current situation and the structure of the future tense. According to the results of the study, the assessment of the past tense differed between the group with the lowest expression of ethnic identity (1 = do not feel at all) and other groups (medium and high expression of ethnic identity). Differences were also found in the assessment of the past tense between the group with low expression of ethnic identity (2 = feel, but very weakly) and the group with the highest expression of ethnic identity (5 = feel completely). The assessment of the future tense also differed between participants with different levels of expression of ethnic identity.

Based on the assessment of the types of ethnic identity, the dominant type of ethnic identity was identified, i.e., positive ethnic identity (82.2%). A relationship was found between the dominant types of ethnic identity and the feeling of being an Armenian. The prevailing group with a positive ethnic identity had values for four different feelings: 50% felt Armenian almost always, 26% felt Armenian fully, 21.9% sometimes felt Armenians, and only 4.1% did not feel Armenian at all. The group of participants with ethno-isolationism had an average value of 5 on the scale for assessing the severity of ethnic identity, where 5 is “I feel it to the fullest extent.” The group of participants with ethnic indifference showed a range of four feelings: 40% sometimes felt Armenian and 40% felt Armenians very weakly, respectively, 10% did not feel Armenian at all and 10% felt Armenian almost always. Most participants with ethno-nihilism (75%) showed very weak feelings of their nationality (“I feel it, but very weakly”), the remaining 25% did not feel Armenian (“I do not feel it at all”). Participants with ethno-fanaticism as a dominant type of identity showed a feeling of being Armenian with a value of 3 (“sometimes I feel it, and sometimes I do not”). Since the study sample is limited in size, future studies with a larger sample are needed to further investigate these relationships.

Conclusion

This study was devoted to the study of the features and characteristics of ethnic identity of student youth, subjective assessment of time and their relationship. The results of this study allowed us to describe the main characteristics of ethnic identity, identify dominant types of ethnic identity, disentangle indicators of feeling a representative of one’s nationality and feelings associated with one’s belonging. Additionally, indicators of subjective assessment of time were calculated separately for the past, present and future tenses. The hypothetical assumptions formulated earlier in the theoretical part were statistically tested using the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis criterion, Dunn’s post hoc test and Pearson’s chi-square criterion. This analysis allowed us to identify statistically significant relationships between the severity of ethnic identity and the duration of residence in Armenia; subjective assessment of time and the feeling of being an Armenian.