1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Indian science classrooms increasingly represent a microcosm of learner diversity, influenced by disparities in socio-economic background, linguistic exposure, and prior academic achievement. Although the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 envisions an inclusive, competency-based education system, classroom practices often reflect a one-size-fits-all approach. Teachers are frequently underprepared to deal with the nuanced instructional demands posed by mixed-ability groups, particularly in the context of science education, which requires conceptual understanding, procedural fluency, and application skills. As noted in Arora & Chander, 2023, despite recognition of inclusive education in policy discourse, pedagogical strategies remain largely undifferentiated. This research addresses this gap by exploring how digital technologies—ranging from interactive simulations to curated video content—can be strategically employed to support differentiated learning in science classrooms.

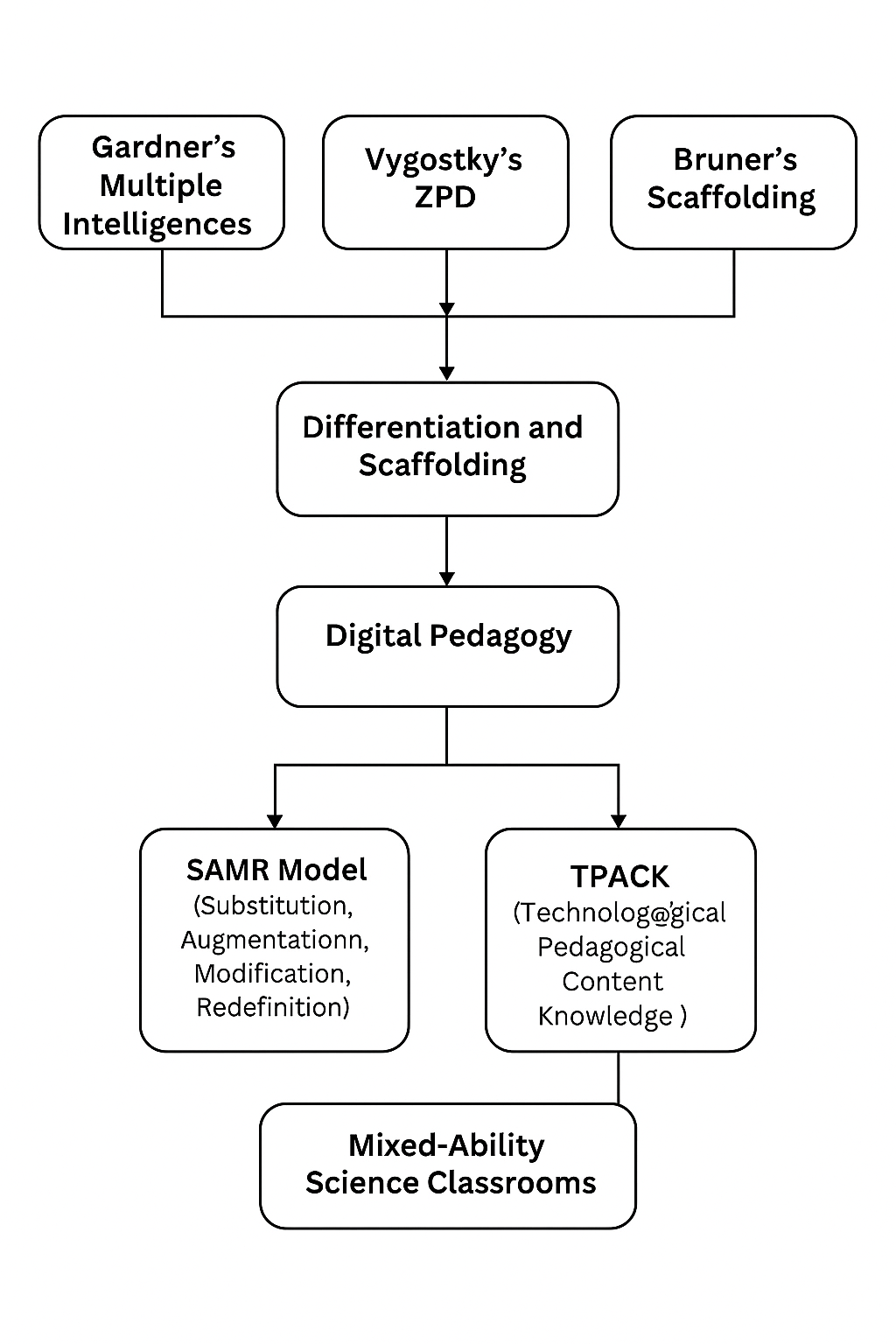

Drawing on Vygotsky’s (1978) Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), the study conceptualizes digital tools as potential mediators between learner capability and curricular demands. The study further leverages Gardner’s (1983) theory of Multiple Intelligences to identify opportunities for individualized instruction. The introduction situates the research within India’s current educational landscape and argues for a model that integrates digital affordances with psycho-diagnostic responsiveness. Educational psychology provides essential frameworks for understanding learner diversity in cognitive and emotional dimensions. In mixed-ability classrooms, theories of cognitive development and individual learning styles are instrumental in shaping effective instructional design. As highlighted in Arora & Chander, 2023, Vygotsky’s ZPD remains central to differentiating instruction. Teachers as observed during fieldwork (Arora & Chander, 2023) often scaffolded content using peer tutoring, concrete aids, and visual reinforcement to match students’ proximal development levels.

Bruner’s concept of scaffolding (1966), which suggests the gradual withdrawal of support as learners gain mastery, was evident in task-based collaborative work where students transitioned from guided instruction to independent problem-solving. This aligns with cultural-historical views of learning as a socially mediated process. Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences theory informed several classroom interventions. For instance, role-play in one government school allowed kinesthetic learners to engage with scientific processes. Another classroom used student drawings to depict scientific phenomena, thus accommodating visual learners. The VARK model also found application, as teachers structured activities using multimedia content and manipulatives to align with learner preferences.

2. Research objectives and questions

Research objectives

The study aimed to:

- Explore how science teachers identify and interpret learner diversity—cognitive, emotional, and linguistic—through informal psychodiagnostics techniques in the absence of formal psychological services.

- Examine the pedagogical integration of digital tools in mixed-ability secondary science classrooms, focusing on how these tools are aligned with diverse learner profiles.

- Evaluate the extent to which established educational psychology theories—particularly Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences (MI), and Bruner’s scaffolding—on differentiated instruction in real classroom settings.

- Develop a culturally contextual instructional framework that connects informal psychodiagnostic responsiveness with digital pedagogy for inclusive and meaningful science learning teaching in Indian secondary schools.

Research questions

To address the above objectives, the study explored the following questions:

- RQ1: How do science teachers in diverse Indian classrooms identify cognitive, linguistic, and emotional learner variability without access to formal psycho-diagnostic services?

- RQ2: What informal diagnostic tools or strategies (e.g., behavioral observations, reflective journals, learning logs) are employed by teachers to guide instructional adaptations?

- RQ3: Which digital tools are most frequently integrated in mixed-ability science classrooms, and how do these tools correspond with learners’ readiness, preferences, and cognitive styles?

- RQ4: How do teachers incorporate psychological theories—such as Vygotsky’s ZPD, Gardner’s MI, and Bruner’s scaffolding—into the planning and delivery of digitally supported, differentiated instruction?

- RQ5: What pedagogical challenges do teachers encounter in implementing diagnostic-responsive digital instruction across varying school types (government, private, urban, semi-urban)?

- RQ6: How do students perceive the effectiveness of differentiated digital learning approaches in enhancing their engagement, understanding, and participation in science classrooms?

3. Educational psychology perspectives

3.1. Cognitive development theories

Educational theories from Piaget, Bruner, and Vygotsky offer essential insights for understanding mixed-ability classrooms. Piaget’s cognitive developmental stages suggest middle school learners primarily benefit from concrete operational tasks involving hands-on activities (Piaget, 1952). Classroom observations affirmed the effectiveness of activity-based science experiments aligning with Piaget's theory.

Bruner’s scaffolding technique was frequently used, demonstrating gradual withdrawal of support as learners became independent (Bruner, 1966). Additionally, Vygotsky’s ZPD provided a foundation for peer-supported instructional strategies. Observations revealed improved learning outcomes when students received scaffolded peer interactions within their ZPD (Vygotsky, 1978).

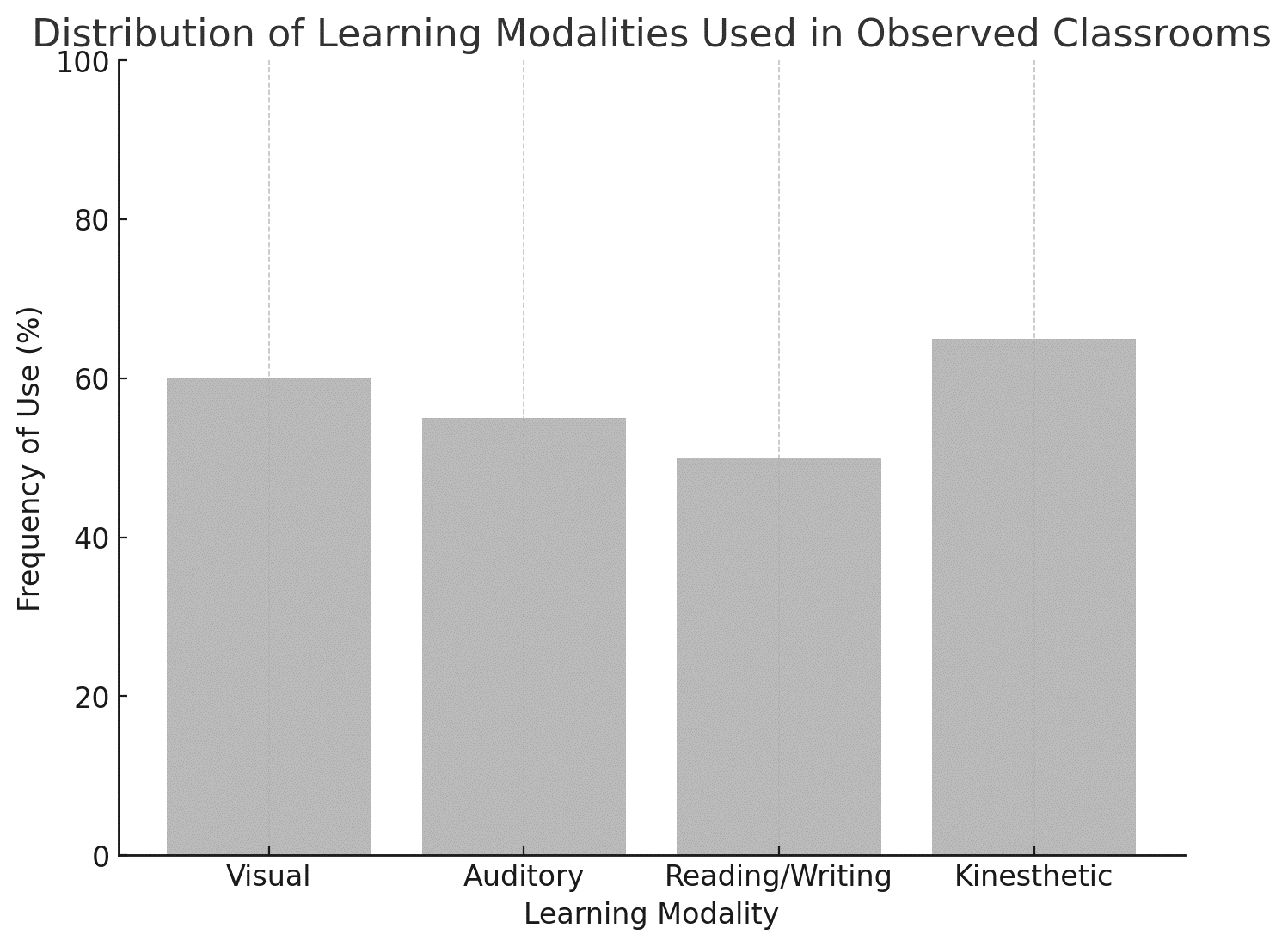

3.2. Learning styles and multiple intelligences

The VARK model (Visual, Auditory, Reading/Writing, Kinesthetic) further guided teachers in lesson planning, ensuring multimodal instruction that catered to varied learning styles (Fleming, 2001). Classroom strategies included animations, peer discussions, worksheets, and role-playing activities, validating Gardner’s multiple intelligences theory.

Table 1. Learning modalities used in science classrooms

|

Modality |

Instructional strategy |

Example from field |

|

Visual |

Use of animations and digital diagrams |

PhET simulations |

|

Auditory |

Oral explanations, discussions |

Peer teaching |

|

Reading / writing |

Worksheets and summarization exercises |

Concept maps |

|

Kinaesthetic |

Experiments, role-plays, model making |

Magnet kit usage |

4. Digital learning tools and techniques

4.1. Integration of digital technology

Integration of digital technology in Indian classrooms, though advocated by NEP 2020, varied significantly based on infrastructure and teacher readiness. The Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework and the SAMR (Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Redefinition) model were employed to assess digital integration levels (Puentedura, 2013). Digital tools utilized included DIKSHA videos for content reinforcement, PhET simulations for interactive visualization, and Google Forms for formative assessments. Teachers who effectively combined technological, pedagogical, and content knowledge achieved higher instructional effectiveness, moving beyond basic substitution towards task modification and redefinition. Nevertheless, disparities existed between private schools with extensive digital resources and government schools limited by infrastructural constraints (Arora, 2023).

In Indian classrooms, particularly in science education at the secondary level, psycho-diagnostic challenges emerge due to the lack of access to formal assessment tools and trained professionals. Teachers often rely on informal techniques such as behavioral observations, anecdotal records, and parental feedback to assess learner needs (Chander, 2011; Arora & Chander, 2023). These observational strategies help teachers adjust instructional strategies in real-time, especially in contexts with limited psychological support infrastructure. Despite the informality, these approaches are crucial for early detection of issues like attention deficits, social withdrawal, and performance inconsistencies. Data gathered during field visits revealed that customized interventions—like peer mentoring, flexible grouping, and visual scaffolding—were frequently deployed based on such insights (Arora & Chander, 2023). The importance of teacher well-being also surfaced as a key theme. Emotionally resilient teachers showed a higher capacity for diagnosing and responding to student needs. Psychological support systems for educators themselves remain a policy gap, suggesting future directions for inclusive frameworks to extend beyond students alone (ResearchGate, 2024).

Digital learning tools, when deployed effectively, can act as cognitive amplifiers, enhancing the learning process by providing opportunities for visualization, interaction, and individualized pacing. In the context of Indian secondary education, the implementation of such tools is uneven and influenced by infrastructural and pedagogical readiness (Zhao & Frank, 2003). The present study adopted the SAMR model (Puentedura, 2013) and the TPACK framework (Mishra & Koehler, 2006) to evaluate the depth of technology integration observed in science classrooms.

The role of digital technology in transforming Indian classrooms has gained prominence through national initiatives like DIKSHA and policy shifts under NEP 2020. In the observed schools, digital tools were integrated to varying degrees depending on infrastructure, teacher training, and learner readiness. These tools ranged from multimedia lessons to interactive simulations and assessment platforms. The study employed the TPACK (Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge) framework to analyse teacher competencies across three intersecting domains: content knowledge, pedagogy, and technology use. Teachers who demonstrated stronger integration of all three domains created lesson plans that moved beyond basic substitution to modification and redefinition, as conceptualized in the SAMR model.

5. Theoretical framework

This research is situated within the broader discipline of cultural-historical psychology, which emphasizes the socially mediated and culturally situated nature of learning and development. Rooted in the theoretical lineage of Vygotsky, the study positions the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) as a diagnostic lens for understanding learners’ potential and framing instructional interventions. The integration of digital tools is not seen as isolated technological upgrades, but as instruments embedded in a cultural context that mediate knowledge construction, peer collaboration, and teacher scaffolding. In this way, the study aligns with cultural-historical approaches by exploring how sociocultural tools—such as language, group roles, and technology—shape and transform the learning trajectories of diverse learners in Indian classrooms.

The conceptual underpinnings of this study are grounded in a triad of psychological and pedagogical theories that support inclusive and differentiated instruction in mixed-ability science classrooms. These include Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences (1983), Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory (1978), and Bruner’s model of scaffolding. Each contributes uniquely to understanding learner diversity, especially when mediated through digital technologies. Gardner’s framework highlights that students possess distinct cognitive strengths—such as linguistic, logical-mathematical, visual-spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, musical, and naturalistic intelligences—which demand corresponding differentiation in content delivery and assessment formats. In the classrooms studied, teachers were seen incorporating multiple representations such as storyboards, practical activities, and reflective logs to align with this plurality.

Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) offers a cultural-historical lens to examine how peer mediation, language, and tools (including digital ones) scaffold student learning. Observations in urban and semi-urban schools demonstrated that when teachers positioned students within their ZPD—especially using peer collaboration and guided digital interactions—engagement and conceptual clarity improved notably. Bruner’s scaffolding model complements the ZPD approach by suggesting gradual release of responsibility to the learner. Teachers adapted instructional pacing and digital tool usage based on informal diagnostic observations, such as real-time feedback and group participation.

These theoretical orientations coalesce in the instructional design adopted in this study. The following conceptual flowchart visualizes how these frameworks interlink with digital pedagogy and psycho-diagnostic responsiveness to address learner heterogeneity in science classrooms.

6. Psycho-diagnostic challenges in mixed-ability classrooms

Addressing the diverse needs of learners in a mixed-ability classroom necessitates that educators employ diagnostic practices tailored to individual challenges. However, formal psycho-diagnostic services, such as the availability of trained school psychologists or educational counselors, remain largely absent from the infrastructure of Indian schools, particularly in government-run institutions. This significant gap places the responsibility solely on teachers, who often turn to informal strategies developed through their own experiences, shared practices from colleagues, or personal instincts honed over time. These adaptive methods play a vital role in understanding student difficulties and customizing teaching approaches to ensure effective learning outcomes.

In many cases, teachers construct observation checklists, maintain learning logs, or record anecdotal instances to monitor and evaluate student behavior, levels of participation, and overall engagement. These records allow educators to identify patterns and recurring issues, such as tendencies to avoid tasks, incomplete assignments, frequent inattention, or lack of verbal interaction during class activities. By analyzing these trends, teachers can pinpoint learners who require targeted modifications to instruction or remedial interventions. Such informal diagnostics become crucial in bridging the gap where formal systems are unavailable, helping educators support students more effectively.

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 has set forth ambitious goals to foster learner-centric environments that promote inclusivity, curriculum flexibility, and competence-based education. Yet, despite these guidelines, the absence of structured diagnostic training leads many teachers to rely on uniform instructional strategies that may not cater to the varied needs of their students. Instead of implementing differentiated teaching methods, educators often struggle to adapt their practices to accommodate mixed-ability groups. This challenge underscores the urgent need for teacher development programs that emphasize psycho-diagnostic skills, enabling educators to navigate diverse classroom dynamics with greater confidence and precision.

In such contexts, teachers often approach diagnostic challenges by developing personalized strategies that align with their unique teaching circumstances. These strategies, despite being informal, have proven instrumental in addressing student-specific needs and enhancing learning experiences in classrooms that lack access to psychological expertise or resources. By leveraging their observations and intuition, educators contribute significantly to creating more inclusive and adaptive learning environments that support students’ individual growth and success.

7. Research methodology

This section expands on the preliminary methodological overview presented earlier, providing a transparent account of research design, sampling logic, data‐collection instruments, and analytic procedures. The level of detail adheres to COREQ guidelines (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007) to ensure replicability and evaluative rigour.

7.1. Philosophical orientation

The study is grounded in interpretivism, recognising that knowledge about classroom practice is co‑constructed by participants and researchers (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). A constructivist stance (Crotty, 1998) shaped the open‑ended data‑generation processes and the inductive–deductive analytic cycle. This ontological and epistemological positioning legitimised thick description, teacher narratives, and micro‑interactional evidence as primary data. This research adopted a qualitative case study approach aimed at exploring how digital pedagogies are implemented in mixed-ability science classrooms, with an emphasis on psychodiagnostics awareness and responsive instructional practices. The design aligns with the interpretivist paradigm, acknowledging the complexity of classroom realities and the subjective meanings constructed by teachers and learners. As outlined in the thesis, the methodology was selected to accommodate the context-specific nuances of Indian classrooms, particularly in government and private secondary schools in Delhi NCR. A constructivist lens, informed by Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory and Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences, guided the research design and interpretation of findings.

7.2. Multiple–case study design

Following Yin (2018), a multiple–case design enabled analytic generalisation across six bounded cases—three government and three private, co‑educational, Hindi‑/English‑medium secondary schools in Delhi‑NCR. Each ‘case’ was a Grade 9 science classroom observed over nine consecutive instructional periods (≈ 360 minutes). Case boundaries were demarcated by school, teacher, and academic term, allowing within‑case depth and cross‑case contrast (Stake, 2006).

7.3. Participant recruitment

Purposive sampling identified six science teachers (4 female, 2 males; teaching experience 5–23 years). Student assent (n = 180) and parental consent followed Directorate of Education guidelines. Pseudonyms protect identities.

Table 2. Data‐сollection matrix

|

Phase |

Instrument |

Purpose |

Sampled artefacts |

|

P1 |

Structured observation checklist |

Map digital‑tool flow, interaction patterns |

36 lesson logs, 216 time‑stamped field notes |

|

P2 |

Stimulated‑recall teacher interviews |

Elicit diagnostic reasoning and tool selection |

6 verbatim transcripts (≈ 54 000 words) |

|

P3 |

Focus‑group student dialogues |

Capture learners affect and perception of differentiation |

12 audio files, 90 student comments |

|

P4 |

Document harvest |

Triangulate enacted vs. planned curriculum |

42 lesson plans, 18 Google Forms, 27 PhET screenshots |

8. Observations

Here are the observations from the data collected.

8.1. Classroom-level digital pedagogy patterns

The study revealed significant variations in digital tool adoption across school types:

Table 3. Summary of digital tool usage in observed schools

|

Tool |

Function |

Context of use |

|

DIKSHA App |

Content delivery (videos, PDFs) |

Used for concept introduction and reinforcement |

|

Google Forms |

Formative assessment and feedback |

Post-lesson quizzes and polls |

|

PhET Simulations |

Interactive visualizations |

Teaching magnetism, atomic structure |

|

PowerPoint |

Structured visual explanations |

Summary slides, visual mapping |

|

YouTube |

Supplemental videos |

Showing real-life applications of science |

Teachers in private schools used a combination of DIKSHA, PhET, and Google Forms, aligning with TPACK competencies. In contrast, government schools largely relied on DIKSHA videos in substitution mode. In one example from School A, a teacher introduced the topic of force using a DIKSHA video. This was followed by a PhET simulation allowing students to change variables such as mass and slope. Students were then asked to complete a Google Form that assessed conceptual understanding.

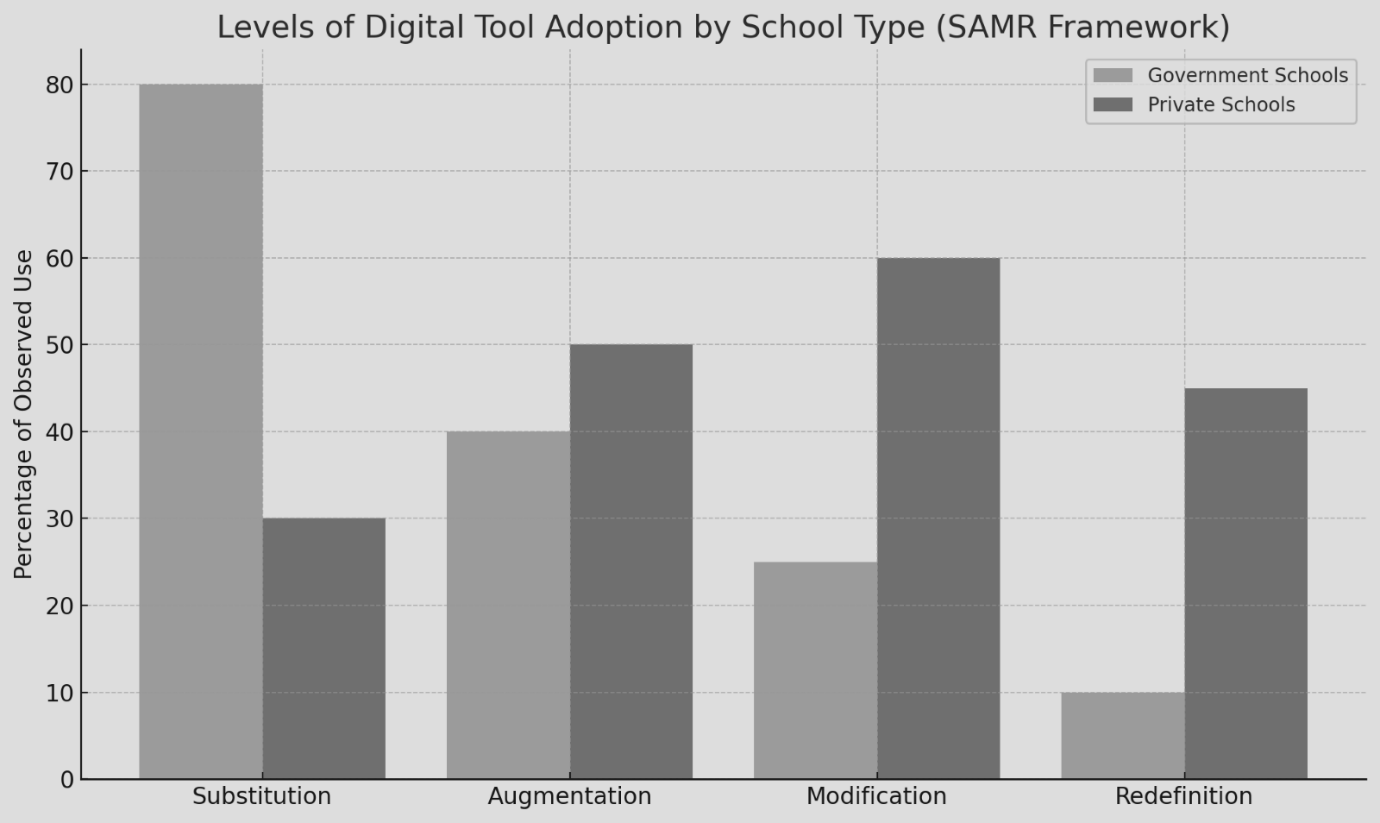

Table 4. Levels of digital adoption in the observed schools using the SAMR framework

|

Level |

Description |

Classroom example |

|

Substitution |

Technology replaces traditional methods without change in task |

Digital textbook used instead of print (Arora, 2023) |

|

Augmentation |

Technology adds functional improvements to traditional tasks |

Online MCQs with instant feedback |

|

Modification |

Technology allows for significant task redesign |

Collaborative Google Docs assignments |

|

Redefinition |

Technology enables previously inconceivable tasks |

Virtual labs and simulations using PhET (Arora, 2023) |

This sequence illustrates a transition from augmentation to modification, as learners interacted with content in non-linear, choice-based formats. At the substitution and augmentation levels, DIKSHA videos and digital worksheets were employed to reinforce textbook content. In classrooms with higher digital literacy, tools like PhET simulations enabled task redesign—aligning with the modification and redefinition stages of SAMR (Arora & Chander, 2023). Google Forms and mobile-based quizzes were used to support formative assessment, providing instant feedback loops that enhanced student engagement. At the substitution level, PDF-based materials replaced textbooks. Augmentation included DIKSHA app videos with rewind capabilities. However, it was in private schools where meaningful modification occurred through collaborative digital tools (e.g., Google Docs) and redefinition with simulation labs (e.g., PhET).

Table 5. School type and integration depth

|

School type |

Digital resource availability |

Integration depth (based on SAMR) |

instructional impact |

|

Private urban |

High |

Modification, Redefinition |

Enhanced engagement, feedback loops |

|

Government semi-urban |

Moderate/Low |

Substitution, Augmentation |

Visualization, basic reinforcement |

Teachers’ digital integration was examined through the lens of the SAMR and TPACK models. The majority of usage remained within the Substitution and Augmentation levels, with higher-order modification and redefinition noted only in select private schools with robust infrastructure.

Anecdote: “We use DIKSHA videos at the start of each topic—it helps set context. But the real change came when we let students play with simulations and change variables on their own.” — Science Teacher, School A

Table 6. Table digital adoption across schools (SAMR-aligned)

|

SAMR level |

Government Schools (%) |

private Schools (%) |

tools employed |

|

Substitution |

80% |

30% |

PDFs, DIKSHA videos |

|

Augmentation |

65% |

55% |

YouTube tutorials, online MCQs |

|

Modification |

30% |

60% |

Google Docs for collaborative tasks |

|

Redefinition |

10% |

45% |

PhET simulations, remote experiments |

Here is a visual representation of digital tool adoption levels in science classrooms across government and private schools, based on the SAMR framework:

- Government schools predominantly remain at the "Substitution" level (80%) with limited progression to "Redefinition" (10%). Substitution is more common in government schools (80%) where digital tools simply replace traditional methods without significant instructional redesign.

- Private schools demonstrate more advanced digital integration, with higher engagement in "Modification" (60%) and "Redefinition" (45%). Augmentation and Modification show higher usage in private schools due to better infrastructure and teacher readiness. Redefinition remains limited overall but is significantly more present in private institutions.

Anecdote 2: Use of PhET simulations (school A) “We used the simulation on magnetism. Students could vary the mass, observe changes… It really helped the quieter ones come forward and explain their understanding without having to write.” (Science Teacher, School A)

Visual and interactive content served dual purposes: clarifying concepts and accommodating non-traditional learners who struggled with written tasks.

8.2. Psycho-diagnostic techniques

Teachers rarely had access to formal psycho-diagnostic tools. Instead, instructional decisions were grounded in continuous behavioural observation, peer group dynamics, and performance logs. Classrooms with stronger diagnostic practices were better able to align tools with learner needs. For instance, learners struggling with English were paired with bilingual peers, and visuals were emphasized. In several cases, role-based group activities helped mitigate withdrawal and boosted self-efficacy among quieter learners.

One teacher from School B shared: "I started maintaining a notebook just to record what topics each child is struggling with. Over time, I could predict who would need a slower pace or more visuals.” Another common practice was the use of informal socio-emotional mapping. Teachers used structured group activities to observe peer dynamics and interpersonal confidence. Instances of social withdrawal or consistent exclusion from peer interactions were flagged and addressed via seating arrangements or peer-buddy systems.

Across contexts, teachers employed informal diagnostic strategies such as:

- Learning logs to identify low performers

- Peer mapping to observe social withdrawal

- Homework completion patterns for behavioral cues

Table 7. Common learning challenges and informal psychodiagnostics practices observed classrooms (adapted from Arora & Chander, 2023)

|

Challenge |

Observation method |

Pedagogical response |

|

Frequent absenteeism |

Parent meeting, health review |

Adjusted pacing, digital catch-up content, modules on mobile devices |

|

Language delays |

Oral probing, written baseline test |

Use of bilingual instruction aids |

|

Attention deficit behaviours |

Behavioural observation log |

Task segmentation, tactile cues |

|

Conceptual confusion |

Pre/post worksheets |

Peer remediation and group review sessions |

|

Inattention |

Behaviour Checklist |

Task chunking, shorter instructions |

|

Inconsistent performance |

Peer interaction monitoring |

Role rotation in group tasks, mentorship model |

|

Anxiety/withdrawal |

Peer feedback, |

Peer buddy system, reduced homework |

|

Poor comprehension |

Repeated questioning, logs |

Visual scaffolds, bilingual instructions |

In several case studies, the teacher's diagnostic awareness led to significant shifts in student performance. One student initially labelled as “slow” due to non-submission of homework was found to be experiencing parental neglect due to migration. A personalized homework schedule and emotional support led to improved attendance and classroom interaction. However, these successes were tempered by systemic challenges. These strategies allowed teachers to identify outliers, especially in classrooms with 40+ students, often without any technological aid. In many instances, diagnostic actions preceded digital implementation.

Table 8. Diagnostic indicator and instructional response

|

Diagnostic indicator |

Observation Method |

Instructional Response |

|

Inattention |

Behavior observation checklist |

Proximity control, task chunking |

|

Anxiety or withdrawal |

Parent-teacher dialogue, journaling |

Reduced homework load, peer buddy support |

|

Inconsistent performance |

Learning log review |

Customized assignments and flexible deadlines |

|

Low group participation |

Peer interaction monitoring |

Role rotation in group tasks, mentorship model |

Such insights led to instructional adaptations, including:

- Group reshuffling

- Simplified task sequencing

- Use of bilingual content

Anecdote: Resource Gap and Student Frustration “We had this video on respiration in English and Hindi, but the terms didn’t match our textbook. The children were confused, and I had to re-teach.” (Teacher from a semi-urban government school). These anecdotes illustrate the tension between policy vision (NEP 2020) and field realities.

8.3. Multiple intelligences and instructional design

Teachers exhibited varying awareness of Howard Gardner’s theory of Multiple Intelligences. While none formally cited the framework, their practices demonstrated alignment. Classroom observations revealed intentional multimodal design in lesson planning. Teachers reported referencing the VARK model and Multiple Intelligences to diversify delivery modes. In science, kinaesthetic learners benefited from hands-on kits, while visual learners thrived on diagrams and simulations.

Table 9. instructional strategies and multiple intelligences

|

Intelligence type |

Observed strategy |

Classroom example |

|

Visual-spatial |

Diagram-based explanations |

Atom structure drawing for Class 9 |

|

Bodily-kinesthetic |

Role plays, model making |

Explaining food chains via group acting |

|

Verbal-linguistic |

Oral narration, journaling |

Students explaining Newton's laws in Hindi |

|

Interpersonal |

Group work, pair collaboration |

Peer explanation tasks in diverse groups |

|

Logical-mathematical |

Simulation-based analysis |

Titration demo using interactive applet |

These adaptive strategies underscore the organic evolution of differentiated instruction—even without explicit training—guided by teacher intuition, field experience, and basic ICT familiarity.

???? Kinesthetic strategies (e.g., magnet kits, role play) were most used (65%)

???? Visual tools like PhET simulations and PowerPoint came next (60%)

???? Auditory strategies such as peer explanation and group discussion were at 55%

???? Reading/Writing modalities (e.g., summaries and worksheets) had 50% usage

Anecdote: “I let some kids draw circuits rather than explain them in words. That’s how they think—visually. And their answers were often more accurate.” — Teacher, School C

8.4 Mapping of key findings with objectives

Table 10. Key insights

|

Objective |

Key findings |

|

Objective 1: To explore how teachers identify and respond to learner variability |

Teachers employed informal psychodiagnostic tools such as observation checklists, behavior logs, and reflective notes. These helped identify challenges like attention lapses, language barriers, and emotional withdrawal. The absence of structured diagnostic tools made teachers depend heavily on intuitive and experience-based methods. |

|

Objective 2: To examine how digital tools are used to support differentiated instruction |

DIKSHA videos, PhET simulations, and Google Forms were frequently used. In private schools, the use of digital simulations led to task redefinition, whereas in government schools, technology was often used at the substitution level due to infrastructural limitations. Teachers aligned content with VARK modalities. |

|

Objective 3: To assess the extent to which psychodiagnostic insights shape pedagogical decisions |

Teachers adjusted grouping strategies, task complexity, and pacing based on behavioral observations. For instance, students with low verbal engagement were placed with peers who could support them through collaborative work. Visual aids and simplified content formats were used for students with language delays. |

|

Objective 4: To analyze the role of visual aids, multimodal tools, and differentiated grouping in enhancing participation and conceptual understanding |

Use of role-plays, science models, realia, and drawing-based science explanations were documented. Students who struggled in pen-paper tests were more responsive in kinesthetic or visual formats. Videos and animation-based tutorials supported recall and engagement. Figure 4.22 (SAMR integration) and Table 5.7 (Digital Tool Use) from the thesis substantiate this. |

9. Results & discussion

|

Objective |

Key insights |

|

1 |

Informal psycho-diagnostic methods like learning logs and socio-emotional observations help detect learner needs |

|

2 |

Digital integration varies widely; private schools use SAMR modification/redefinition levels more effectively |

|

3 |

Diagnostic responsiveness shapes instructional alignment more than the availability of digital tools |

|

4 |

Multimodal teaching, rooted in Multiple Intelligences and VARK, results in better inclusion and engagement |

Objective 1: Learner variability and diagnosis

Findings support the view that informal psychodiagnostics—despite being intuitive—were instrumental in identifying and responding to learner needs. These practices echo Vygotsky’s idea of individualized scaffolding within the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), though in a non-institutionalized form. The absence of systemic diagnostic infrastructure reveals a significant policy gap.

Objective 2: Digital differentiation

Digital tools acted as cognitive enablers when employed thoughtfully. In contexts where the TPACK framework was applied, learning experiences moved beyond surface engagement to deeper conceptual understanding. However, unequal access to digital tools widened the instructional gap between private and government schools.

These approaches affirm the theoretical alignment with Gardner’s intelligences and Vygotsky’s ZPD — where peer scaffolding allowed students to bridge conceptual gaps.

- The findings of this study emphasize that the success of digital and diagnostic strategies in mixed-ability classrooms depends not only on tools and content but also on the teacher’s preparedness. Despite the availability of digital infrastructure in several schools, there was limited translation into inclusive pedagogical practices due to gaps in teacher training.

- Feedback from students (field interview notes) suggested:

- Preference for blended formats (video + teacher support)

- Improved conceptual understanding when digital content was interactive

- Reduced anxiety in peer-supported environments

Objective 3: Pedagogy informed by diagnosis

In alignment with Gardner’s theory, differentiated instruction strategies were evident—especially among teachers who triangulated observation with learner preferences. This finding validates the hypothesis that digital pedagogy must be guided by diagnostic insight to be truly inclusive.

Objective 4: Visual and kinaesthetic strategies

Multimodal instruction enhanced student engagement and participation, particularly for students who struggled with conventional assessment formats. Role-play, peer group activities, and tactile experiments became vehicles for expression among kinaesthetic learners.

10. Results and conclusion

This section synthesizes the core findings from classroom observations, teacher interviews, student work samples, and institutional documents across a diverse range of government and private schools in the Delhi NCR region. The data were analysed using a combination of thematic coding and alignment with the research objectives, specifically focusing on psychodiagnostic awareness, differentiated instruction, and the integration of digital tools in mixed-ability science classrooms. This section presents the empirical findings of the study drawn from field observations, teacher interviews, student feedback, and visual documentation across mixed-ability science classrooms in Delhi NCR.

The results affirm that meaningful digital integration in mixed-ability classrooms cannot be decoupled from diagnostic consciousness and pedagogical flexibility. In the absence of clinical tools or professional support, Indian teachers are building context-sensitive, humane strategies that reflect both their constraints and their commitment. However, for the model to scale, policy frameworks must include diagnostic training modules, ICT grants for schools, and localized digital content aligned to curricular goals.

Challenges in diagnostic-responsive instruction

Despite promising practices, significant systemic barriers inhibited deeper implementation:

- Infrastructure gaps: In at least four government schools, there was only one smartboard per school shared across classes.

- Training deficits: Teachers in these settings had only attended 2-3 DIKSHA modules with no hands-on ICT workshops.

- Overcrowding: Student-teacher ratios exceeding 50:1 made individualized attention nearly impossible.

- Psychodiagnostic methods for teachers: Supporting teacher emotional health enhances their diagnostic capacity, as emotional bandwidth correlates with student responsiveness.