Defectology and the South African context

The shifts in the South African educational (and political) landscape are not dissimilar to the situation that Vygotsky faced in 1924 when he left Gomel. Much like Moscow in the 1920s, the new democratic dispensation in South Africa post-1994 was concerned specifically with redesigning education so that it would include all children. This change attempted to move the country away from a notion of deficit, which in the past had been informed by IQ scores showing that Black and White children were intellectually different, with Black students identified as having sub-optimal IQs, effectively pathologizing Black students as developmentally delayed (Dubow, 1991). Considering this and against a political background of segregation, Black children were given inferior education termed ‘Bantu’ education, where students were not permitted to learn subjects such as mathematics or science. Similarly, White students who were differently abled were sent to ‘special’ schools, effectively hidden away from the ‘normal’ public. The new democratic dispensation of 1994 was, therefore, keen to shift this negative view of students by developing a policy of inclusive education for all.

The purpose of this paper is to mobilize Vygotsky’s defectology work to understand inclusivity in a multicultural, multilingual context like South Africa. It is important to note that Vygotsky’s defectology is not synonymous with how we use the term ‘special education needs’ today. The field of defectology in Russia in his time encompassed the deaf, blind, seriously developmentally delayed, and students with speech and language deficits (Petrovsky & Yaroshevsky, 1998). Blind and deaf students would, of course, be considered neurotypical, while students with serious developmental delays or speech and language impairments would be considered neurodiverse in the 21st century. What I note here is that defectology was not specifically engaged in the study of children who would today be found in inclusive classrooms presenting with behavioral, mental health, or learning difficulties where the etiology of such disorders is found in the social rather than the individual. However, the theoretical foundation of defectology that locates deficits within a dialectical relation between the individual child and the social context certainly provides a basis for this work in inclusive education. Indeed, the move to use defectology to describe learning difficulties, mental health challenges, and emotional behavior has developed since Vygotsky’s time (Daniels and Lunt, 1993; Smith-Davis, 2000; Malofeev, 2001; see esp. Smagorinsky (2012) for a discussion on mental health and defectology). Specifically, Vygotsky’s assertion that how one responds in a social situation to a child presenting with a ‘disability’ has a powerful impact on the child’s development.

Responding to a child with Down Syndrome, for example, as differently abled rather than disabled, in a context of care and respect impacts how this child experiences him/herself in the world. A child with DS has no notion that there is any kind of deficient functioning until s/he encounters the social realm where people react either with respect and care (as Vygotsky would argue they should) or treat the person simply as deficient. It is in the response from the social realm that development unfolds. This understanding of how mediated interaction can positively impact developmental delays informs this paper. I note, though, that the current paper deals with an inclusive model of pedagogy premised on social justice by focusing more on educational delays as barriers to learning that cause developmental delays rather than focusing on organic disability.

Inclusion, here, refers both to students who have learning/behavioral diagnoses as well as to students who are neurotypical but present as learning disabled. In relation to neurotypical students, in contexts where social upheaval has led to homelessness, poverty, food insecurity, and violent living conditions, these students simply have not had access to the kind of cultural tools needed for development. For example, a news item on the radio in Cape Town recently reported that 1,600 children in the Western Cape province (where this paper is located contextually) were admitted to hospital for serious gunshot and knife wound-related injuries in October and November 2024 (Cape Talk, 26/11/2024; 6:43 a.m.). In such a context, the source of a student’s apparent developmental deficiency is not natural but cultural. For example, research (Stewart, 2015) indicates that trauma signs and symptoms mimic those of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). We may well anticipate that children who have suffered gunshots or knife wounds can present with signs of ADHD and be medicated rather than receiving the requisite help for trauma-related responses: a missed opportunity to intervene in a way that is affirming and not pathologizing. This is why Vygotsky’s view of special needs as being located not solely in the child but in the socio-cultural context in which the child is developing is of central interest to countries such as South Africa. The current paper seeks to answer two questions:

What can an inclusive, developmental pedagogy look like?

How do students experience this type of pedagogy in a university setting?

Sociocultural context

Like Russia in the 1920s, South Africans have experienced monumental changes to their way of life since the end of apartheid. While apartheid may be over, the historical traces of inequality persist in all aspects of South African life, especially in schooling. Locating any difficulties with learning or emotional regulation solely within an individual child fails to account for the disparate upbringing, education, and access to cultural tools faced by different children in South Africa. The truly transformative nature of Vygotsky’s approach to defectology lies, for me, in the positive view of what traditional psychologists would see negatively as a deficit. It is society’s response to differently abled individuals that must change, not the individual her/himself. This is well captured by Vygotsky’s contention that the education of the blind child is “…not so much the education of blind children as it is the re-education of the sighted. The latter must change their attitude toward blindness and toward the blind. The re-education of the sighted poses a social pedagogical task of enormous importance” (p.86). In an inclusive pedagogy, instead of seeing a child as ‘stupid’ or deficient, imagine viewing all children as having something to offer the world; a perspective that all students can attain knowledge, but some may do so faster and others more slowly.

While Vygotsky’s defectology is generally used to discuss children with developmental delays of organic etiology, the current paper will focus on neurotypical students—many of whom have serious educational delays due to poor schooling, violent contexts, mental health issues, sometimes social dislocation (as youngsters), and poverty. While the model of pedagogy outlined here is used with neurotypical students, I will argue that this model can be equally effective when teaching differently abled students—either in schools or in higher education. The study reported here is located at a university in South Africa. In this institution, depression and anxiety levels among students are 45,9%, significantly impacting how students can approach their work successfully (Van der Walt, Mabaso, Davids & De Vries, 2020). Even the most ardent Western psychologist trained in psychopathology would find it difficult to locate the etiology of these disorders solely within individual deficits. When almost half of the student body suffers from anxiety and depression, the causes must lie in the dialectical relationship between individual and social context—demanding a pedagogical model capable of reaching and teaching all students.

The Teach-Assess-Teach model of pedagogy

The model of pedagogy described in this paper draws on the work of Vygotsky (1986), Hedegaard (1998; 2020), Craig (1996), and Wood et al. (1976). For Vygotsky (1986), the only pedagogy that is useful is that which moves ahead of development, working on what he refers to as ‘buds’ of development. In this pedagogical praxis, learning leads development through the guidance of a culturally more capable other in a unique social space called the zone of proximal development (ZPD), where abstract concepts—initially external—are internalised by the novice. These abstract concepts, Vygotsky (1986) calls scientific concepts, and they are decontextualised, abstract in nature, and can only be acquired through teaching. Conversely, although dialectically entailed, everyday concepts are those concepts that the child uses to make sense of the abstraction being taught. For knowledge to develop, one needs scientific and everyday concepts to be intertwined in the developmental process. A scientific concept alone is hollow and devoid of sense for the child; while the everyday concept provides sense to the scientific concept, the scientific concept comes fully into conscious awareness through the everyday, and this leads to the acquisition of a meaningful concept. How exactly one intertwines these concepts in development is outlined in Hedegaard’s double-move, where “…the teacher guides the learning activity both from the perspective of general concepts and from the perspective of engaging students in ‘situated’ problems that are meaningful in relation to their developmental stage and life situations” (Hedegaard, 1998:120). The engagement in discrete tasks in classrooms can be facilitated, I argue, using scaffolding—a form of task-related methods for engaging students in a lesson (Wood et al., 1976).

A brief caveat, however: scaffolding is not mediation; while mediation is geared toward development, scaffolding is aimed at discrete tasks (Smagorinsky, 2020). A scaffold can be seen metaphorically as a scaffold used in building; as the building becomes more stable, the scaffolds are removed. So too in a teaching situation: when the student becomes more proficient in problem solving, the scaffold for a specific task is withdrawn. Scaffolding is not a Vygotskian term and is not related to development—as mediation is—because it takes place in real time during a lesson, while mediation unfolds over a series of lessons and over time. For the purposes of the model I have developed, though, scaffolding can be used to engage students in discrete tasks during single lessons. The types of scaffolding one can use take the form of recruitment, demonstration, direction maintenance, frustration control, and reduction in degrees of freedom. These pedagogical tools are useful for completing tasks in a lesson and form part of the teaching used in the Teach–Assess–Teach (TAT) model I outline in this paper.

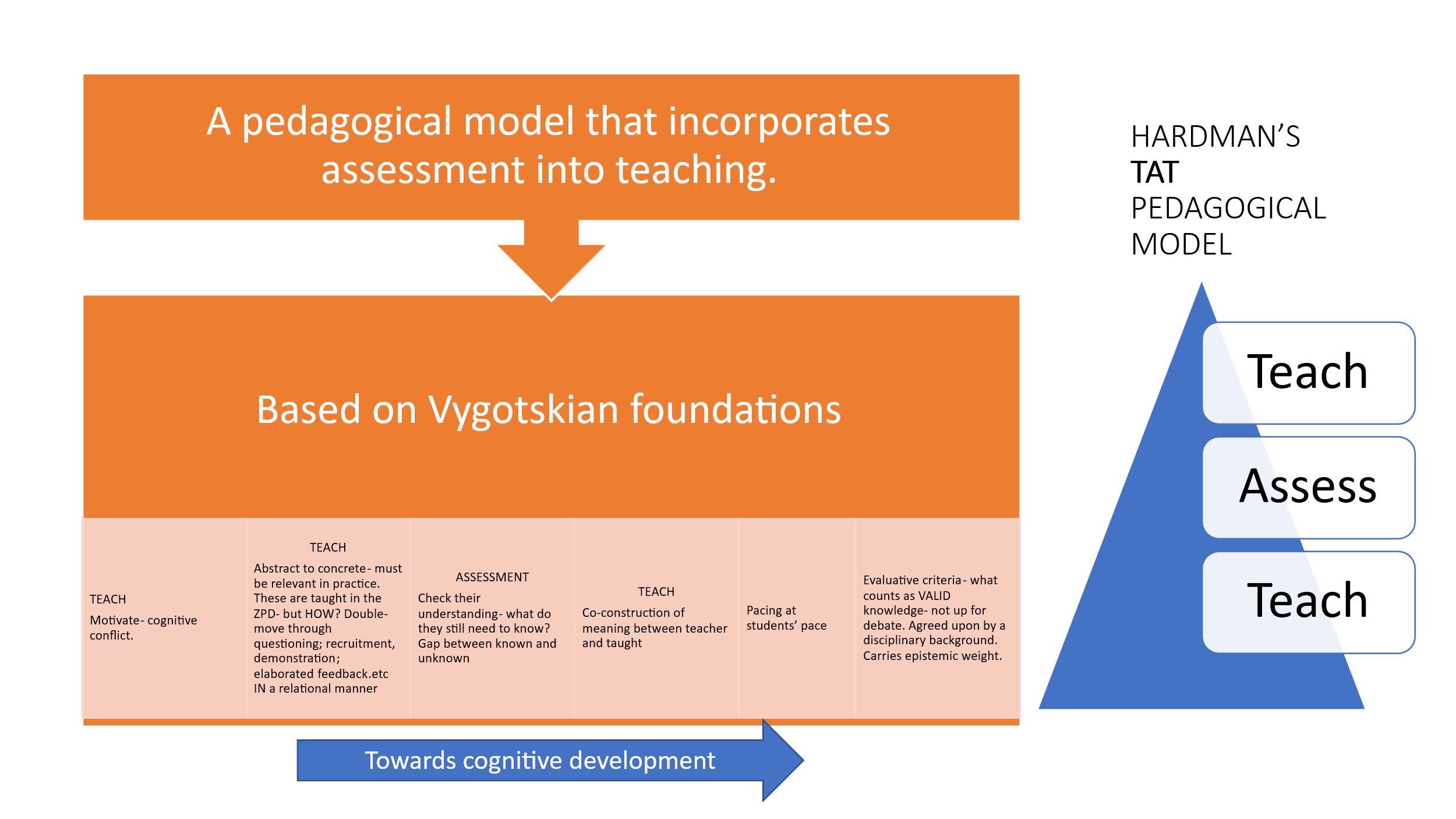

The TAT model of pedagogy owes much to the work of Craig (1996) and her colleagues at the former Natal University in the 1990s. Tasked with opening access to the university for students who were previously denied access, the Teach–Test–Teach (TTT) programme sought to afford students’ access to university through a structured programme. While the TAT model is concerned with inclusive pedagogy and not with access per se, much of the logic of the TTT programme is useful in classroom contexts. For Craig (1996), for students to acquire knowledge, they needed to develop the ability to metacognitively reflect on their own approach to knowledge. This requires that the student can distance themselves from the opinions and beliefs they hold and develop arguments based on evidence drawn from reliable sources. This, in turn, requires that students can judge what counts as valid evidence by appreciating the disciplinary norms and epistemic weight underpinning the evidence they draw from—say—journal articles (Muller, 2014; Craig, 1996). A student must be able to step out of their everyday understanding to deal with novelty. Assessment in the TAT model is continuous and serves the function of ascertaining what students know and what they still need to know. Importantly, feedback is elaborated, and what counts as a valid answer is set by disciplinary norms. Pace is determined more by the students than by the teacher, with control over pace lying more with the students than with the teacher. Students are required to engage in dialogue during lessons, and questioning is encouraged. The focus on dialogical interaction as important in learning is well established in the literature (Lefstein & Snell, 2013; Khun, 2018; Howe, Hennessey, Vrikki & Wheatley, 2019; Dessingue & Wagner, 2025). Very specifically, the focus of dialogue is on developing what Mercer and colleagues refer to as exploratory talk that is representative of reasoning (Mercer & Wegerif, 2002; Mercer & Dawes, 2008; Mercer, Wegerif & Major, 2019). Figure 1 presents a graphic depiction of the TAT model.

As can be seen in Fig. 1, the first step in this model is to create cognitive conflict in the student. Motivation, for me, draws much on Piaget’s work where disequilibrium forces a student/child to seek resources to overcome dis-ease. In this way, motivation is not external but internal and is driven by an uncomfortable disequilibrium that must be overcome for the student to learn. While external motivation, such as praise or an interesting hook to start a lesson, is useful in learning (all learning requires motivation), I argue that external motivation is transient and does not ensure that a student stays engaged in what unfolds in the lesson. Once the student is motivated to learn, the teacher can begin teaching using the double-move, situating the abstract concepts being taught in the situated lived experiences of the students. Scaffolds such as questioning can serve to keep engagement on specific tasks. Assessment is then used as a mid-point in teaching to ascertain what the students know and what they still need to learn. This knowledge informs the next round of teaching. Teaching unfolds in a space that is characterised by respect and an ethics of care. Here, an ethics of care recognises the unique student and what they bring to the lesson and adopts a moral stance towards teaching/learning, recognising that learning is about both cognitive and affective development. It is difficult to appreciate how a student could learn in a space where they feel threatened or unable to voice their own opinions. Pacing is controlled by the teacher but loosely so, enabling students to move at a pace that enables them to learn. Feedback here is elaborated, and what counts as a valid answer—in regard to disciplinary norms—is outlined. Students are encouraged to provide reasons for their answers, whether right or wrong, and questions such as ‘how’ and ‘why’ provide the impetus for discussion.

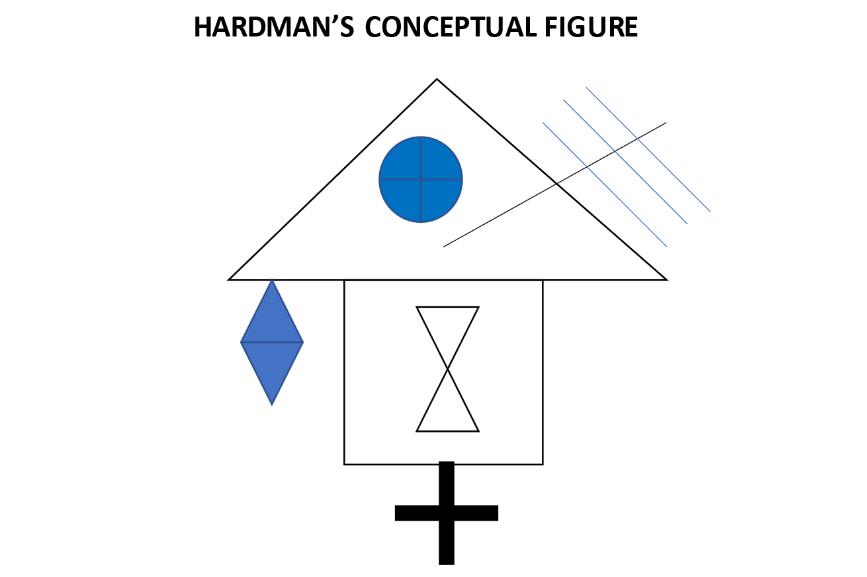

In the study reported in this paper, students are learning about theories of development; very specifically, in this paper, they are required to engage with Piaget’s notions of assimilation and accommodation. To create a space of cognitive conflict, students are given 30 seconds to look at Fig. 2 below and then given 30 seconds to replicate this diagram. This task seeks to challenge them as they are required both to solve this figure and to indicate how they remember it.

It is impossible for a human brain to remember all the elements of this diagram without some kind of cognitive structure to do so. There are simply too many elements for the brain to remember. When asked how they remembered the diagram, some students indicated they used their everyday concepts; the diagram looks like a house with a roof and an aerial. Almost everyone remembers the cross because it is a religious symbol that has different meanings for different religious groups. Everyday concepts alone, however, are insufficient to remember this diagram; three central abstract concepts are needed to do so: an understanding of shape, colour, and number. Students often express surprise that they had used these abstract concepts to remember the diagram because they did so unconsciously—that is, in a fossilised manner and without reflecting on it, as these concepts are deeply embedded in their understanding. Once students were motivated to engage with the teaching, the lesson proceeded to introduce Piaget’s (1976) notions of assimilation and accommodation. These concepts are, themselves, imbued with cognitive conflict because they do not resemble what is meant in English by these terms, forcing students to discuss among themselves what these concepts can mean to them. This part of the lesson was conducted through group work during which students discussed the concepts and provided examples—examples they could share with the class—of these concepts.

Methodology

This study adopts a case study design within an interpretivist paradigm. A case study is useful for in-depth analysis that focuses on how something happens in the context. As this paper addresses a question that requires interpretation, the study is located within an interpretivist paradigm. The theoretical basis for this paper, cultural-historical theory, lends itself well to an interpretivist paradigm.

The students

A group of students registered for an honours course in Education at a large university in South Africa volunteered to take part in this study. There were 52 postgraduate students who took part in this study, with an average age of 36 years and a range from 24 to 56 years. Forty-eight students were in-service teachers, and the remaining four students were not teachers. Thirty of the in-service teachers were primary school teachers, and 18 were high school teachers. The four students who were not teachers were unemployed and studying full-time towards an honours degree. Of these four students, three were male and one was female. The lecturer (who is also the researcher) is a white female who has been teaching at the university for just over two decades. This module introduces students to theories of development and learning, beginning with the work of Piaget, which is the focus of this paper. The module runs for 12 weeks, with sessions once a week lasting 2 hours. Students are usually assessed by means of a single essay at the end of the module. In this group, however, given that it tests a novel pedagogy, students were awarded marks for engagement in discussions throughout the module. This constituted 20% of their final mark, with the essay accounting for the other 80%.

The study took place at a large university in the Western Province of South Africa. This university has approximately 5000 academics and 26000 students across its various campuses. Demographically, the student body is approximately 25% Black African and 22% white; the remainder are either from other racial groups or are international students.

The lecturer

As the lecturer and researcher in this study, I found it important to reflect on my own engagement in this teaching/learning space. I am a white woman with 24 years’ experience in teaching, learning, and educational psychology. I consider myself to have a distinctly different demographic profile from most of my students in this particular study. The privilege (perceived and real) entailed in being white in South Africa, given its history, is not lost on me. I felt it was important to constantly reflect on the asymmetrical power relations that could easily emerge in this course. This required giving time and space to group discussions and encouraging dialogues, balancing the need for students to acquire the correct concepts in the course with the need not to completely disregard dialogue that may not have been directly on topic. It also required that any coding of the work be undertaken by me and another researcher.

Analysis

Data was collected in the form of exit slips, which asked students for their opinions on: 1) what aspects of this pedagogy worked well, and 2) what did not work and could be improved.

Findings and discussion

Students’ perceptions of the pedagogical model

In the final lecture, students were given an exit slip to answer two questions: 1) what they liked about the pedagogy, and 2) what could be improved in the model. Two themes emerged from the data: increased interaction and more accessible content.

Increased interaction

This theme pointed to the fact that students experienced increased interaction in the lessons. Research indicates that interaction in lessons—where students are able to gain talk time and engage with each other—is optimal for learning (REF).

PT: (36-year-old female primary school teacher) The readings and interactive nature of the lectures helped me remain engaged.

JS: (25-year-old female high school teacher) XX’s (the lecturer) pedagogies were amazing! The examples, continuous interaction in class, and overall understanding of context were very useful for me.

BN: (37-year-old male high school teacher) Learning from colleagues and their ideas on how to teach certain subjects, as well as the activities, were valuable.

AW: (26-year-old female high school teacher) I think engagement is one tool teachers can use to bridge the gap between not understanding and gaining knowledge, and Prof XX is very engaging.

SB: (35-year-old high school teacher) Interactive lessons.

What we can see in the extracts above is students’ appreciation of the interactive nature of the pedagogy used in this module. This plays out both in terms of learning from colleagues (BN) as well as from the interactive nature of the lectures (PT).

A second theme that emerged from the exit slips was the accessibility of the content covered in the course.

Accessible content

The following are responses to the prompt: What worked pedagogically in this course?

JK: (30-year-old male primary school teacher). I thoroughly enjoyed this course. Keep being you, Prof. The best!!! The readings were hard, but you made them really user-friendly. Your explanations of the concepts were so clear, and your real-life examples really helped me understand the concepts because I haven’t done any psychology before.

MN: (29-year-old female primary school teacher). I liked that you used relatable examples to explain concepts. This made the work easier to grasp because I could link it to something I understand.

SD: (34-year-old high school teacher). The structure of how each concept was approached was excellent. Each concept led into the next seamlessly and made it easy to understand.

IV: (48-year-old male high school teacher). Her methods are so great that I understood every concept, even though I don’t have a psychology background. Every section was engaging—that is what works most.

SJ: (30-year-old primary school teacher). I really enjoyed the teaching process. The explanations/module were well explained and easily digestible.

As can be seen above, students found that this pedagogy made concepts more accessible by being engaging and by using real-life examples to facilitate understanding. Regarding aspects that did not work about this pedagogy, students indicated that nothing was problematic; however, 7 out of 52 expressed a desire to learn more about neurodivergent students.

Conclusion

This paper began as a 21st century pedagogical response to Vygotsky’s defectology. The paper outlines a pedagogical model for inclusive education, where students’ voices are included in the co-construction of meaning in an honours module at a university. The TAT model discussed in this paper aims to include students in meaning making, through teaching, assessment and re-teaching in such a manner that no student is left behind in the class. The paper aimed to develop a model of inclusive pedagogy and to describe students’ experiences of this model. Results suggest that the pedagogical model provides students with an interactive space and makes the work more accessible. This is a small case study, and a caveat needs to be inserted about its generalisability. There appears to be promise in this pedagogical model to include the voices of all students. However, further research is required in this area.