Introduction

Thoughts about the future are of paramount importance for adolescents and youths. Thinking about the future and acting in accordance with this is a life-long task, but it receives significant development in youths [Andreeva, 2023; Isaeva, 2022; Baikeli, 2021; Fonseca, 2020]. The present research considers changes in the image of the future from adolescence to emerging adulthood which characterize the contemporary youth. Future t ime perspective is a kind of cognitive motivation of the individual characteristic of understanding and planning by a person of his/her future, it can also influence individual behavior at present through forming aims and awareness of achievements [Jiang, 2016]. Former research showed that future time perspective can positively influence academic performance, strategy of education and educational outcomes [Janeiro, 2017; Shilova, 2022; Shilova, 2022a], and negatively influence dependence on the internet and other kinds of addiction [Kim, 2017; Przepiorka, 2019]. People with a well-developed time perspective can sacrifice short-term benefits in favor of long-term results, and this ability to postpone momentary pleasures allows them to achieve higher results [Wang, 2022].

Lack of a positive future perspective may hinder tasks of development and may be a serious risk factor because a time perspective is crucial for well-being, motivation, and behavior [Egorenko, 2022; Kooij, 2018; Parola, 2022]. Ideas on the future are an important part of life for any person, and the concept of the “psychological future” is addressed to the cognitive sphere and is connected with a mature attitude of an individual to the time of his/her life [Belogaj, 2018]. The duration of the “expected future” affects a person’s behavior at present, it significantly increases in the youth [Levin, 2000]. Time categories or frames connect personal and social experiences, they give meaning, order and consistency to life events, they affect the ability to foresee and plan future desired results. Time categories refer to thoughts, ideas and feelings which people experience about their future [Parola, 2022]. Forecasting one’s own future, which in our culture is associated first of all with professional self-determination, selecting a university and future job, is one of the important markers of growing up.

At present, young people have to think about the future in a quickly changing cultural and social context. From the beginning of the 21st century professional employment and stability, which gave a safe foundation for seeing the future have been replaced by a new social structure of labor and new forms of employment. The modern world of work is characterized by temporary forms of employment, lack of employment guarantees, projects limited in time, high competition in the labor market and fragmented career paths. Transition to adult life from this point of view has changed from simple social determinant to individual personal choice that is built in socio-cultural contexts, and the criteria of reaching adulthood have become more flexible and subjective [Parola, 2022]. The f uture “I” can be considered as a project of building the “adult self” from the point of view of hopes and fears which provide the foundation for forecasting future events, setting tasks , forming plans, studying alternatives, taking responsibilities and self-development management [Gunawan, 2021].

The m odern situation in which institutionalized forms of growing up “create a challenge for classical psychological approaches – cultural-historic and activity-based” [Polivanova, 2016], and a life scenario no longer resembles an uncontested "beaten track" in which everything was in a strict order: education, work, family.

The question of the sequence of changes in the idea of the future as an understanding of growing up becomes important, accordingly. The aim of this research was to establish the nature of age-related changes in the image of one's own future in the modern social and cultural situation in the period from adolescence to adulthood.

Organization of the research process, features of the tools used and sampling

The sample of our research was 1538 people from 14 to 28 years old (610 young men and 928 young women). The respondents were grouped into four age groups in accordance with the fundamentals of cultural and historical psychology and current trends in psychological research: adolescence (14 years - 304 people), early youth (15-18 years – 500 people), late youth (19-23 years – 381 people), the emergence of adulthood (24-28 years – 383 people) [Vasil`eva, 2007].

Invitations to the study were sent through educational organizations in Russia of various levels of education. The invitation contained a link to the study, which could be completed on any personal computer, in a place convenient for the respondent. The questionnaire was compiled using the "SurveyGizmo" service.

The research was conducted using the I.S. Kon method “I in 5 years” and the J. Nutten method of unfinished sentences for determining future time perspective.

I.S. Kon’s methodology was used for identifying content and future forecasting components of the research participants. Respondents wrote essays “I in 5 years” without limits to the time and volume. A f ive-year time horizon allowed them both to detach from contemporary characteristics of their personality and to see the foreseeable perspective. The texts received were analyzed with the help of statistical software program package “R”: a graph was made of relationships and words which respondents used more than others, and cluster analysis was done with the Ward method. Cluster analysis made it possible to group summaries of essay texts in each age group and subsets of words with topics preferred by respondents.

The J. Nutten method of unfinished sentences was used to identify time perspective. Respondents were to finish a suggested phrase writing about their wishes, the length of the statement did not matter. The method version was used that contained 20 phrases in the affirmative, for example, “I want…”, “I hope…” and 10 phrases in the negative (”I don’t want…”, “I am afraid…”). Data processing was based on Nutten’s recommendation about using only time categories specific to this sample. The following categories turned out to be significant for our sample: school and professional education (periods of social and biological life), professional autonomy (in the adulthood period), the open present (refers to the entire period of life – as a reference to the wish of having certain qualities and skills (to be intelligent, know a foreign language perfectly and so on)). To ensure validity, the analysis of the received statements was implemented by five experts – psychologists and educators who have a scientific degree. Discrepancies in the interpretation of the results were discussed collectively. Statistical data processing was carried out using ANOVA analysis of variance. With the help of the conducted analysis, the age preferences of respondents in choosing time intervals were studied.

Research results

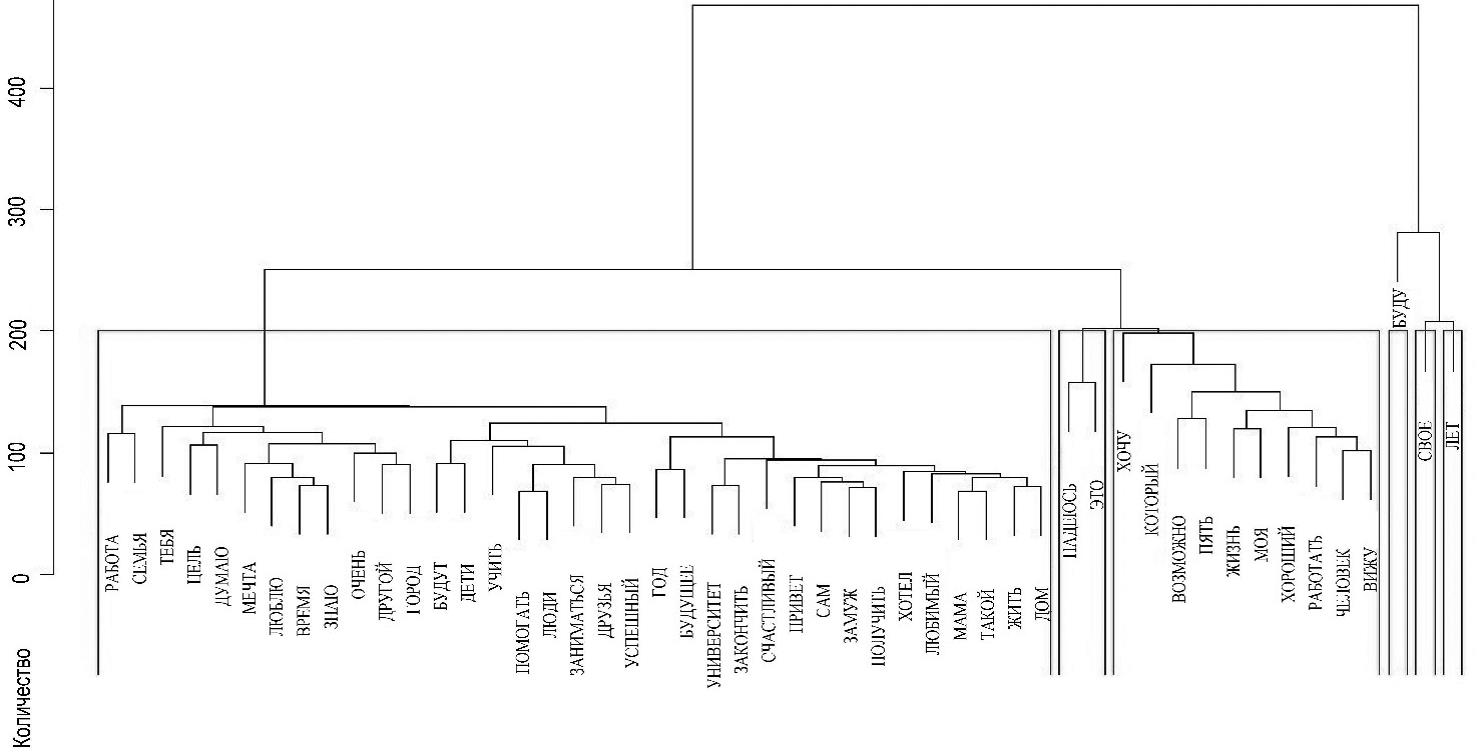

As part of the analysis of the essays on the topic "I am in 5 years", we received data on the relationships of words used by respondents when describing their own future most often (Fig.1). There were 15988 words in 1538 texts. Prepositions, proper names, numerals and words that have no meaning were removed from the analysis.

Рис. 1. The average image of the future of respondents aged 14-28, compiled on the basis of the most commonly used word relationships (n=15988)

Рис. 1. The average image of the future of respondents aged 14-28, compiled on the basis of the most commonly used word relationships (n=15988)

The figure represents an average image of the future of respondents aged 14-28, compiled on the basis of the most commonly used word relationships. The graph shows that the relationships of words are nonlinear in nature, they allow us to identify semantically close words and assess the measure of their semantic proximity. In the center of the graph, many relationship lines converge to words such as "I can", "I want", "I hope", "work", "do", "I see", "goals", "I know", "maybe", "I will be". Accordingly, these words are most often involved in semantic relationships , with the help of which young men and wom en describe their idea of the future.

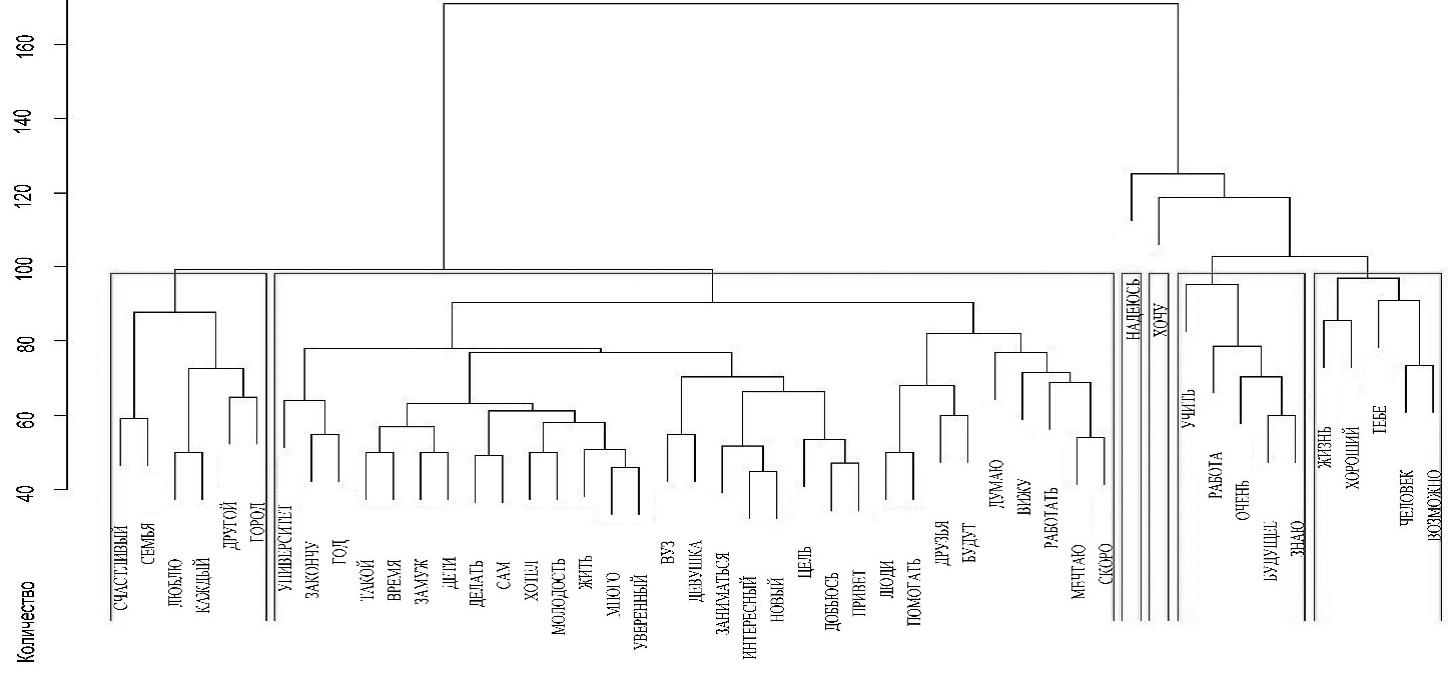

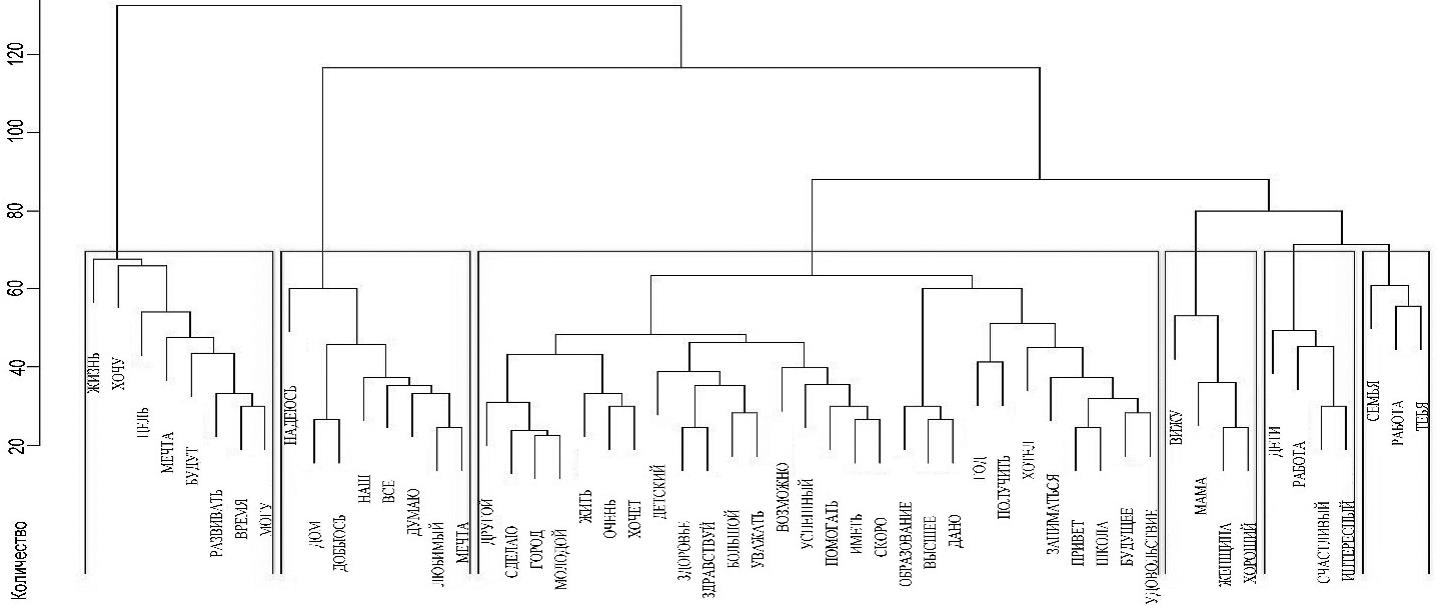

Fig. 2. A dendrogram of the use of words in the description of the future by teenagers aged 14, built using the Ward method (n – 304)

The significant aspects of the image of the future of 14-year-olds are the following. The cluster of the maximum size includes "desires and dreams related to the future, friends, mother, children and family, classes," etc. For teenagers, these words are interrelated, since they fell into one cluster without being divided into topics. On the Y axis, this cluster is located below the others, respectively, it has a subordinate value. A cluster in which the words "I want" combine "opportunities, life, a good job, a good person" is of interest. Further, the cluster that combines the words "I hope" and "this" carries the same scale of influence along the Y axis as the word "I want". The last three clusters containing one word each have the minimum size. These are the words: "I will", "my", "years". The cluster with the word "I will" has a big difference from the rest on the Y axis. This word connects all clusters, representing the core of the image of the future of teenagers.

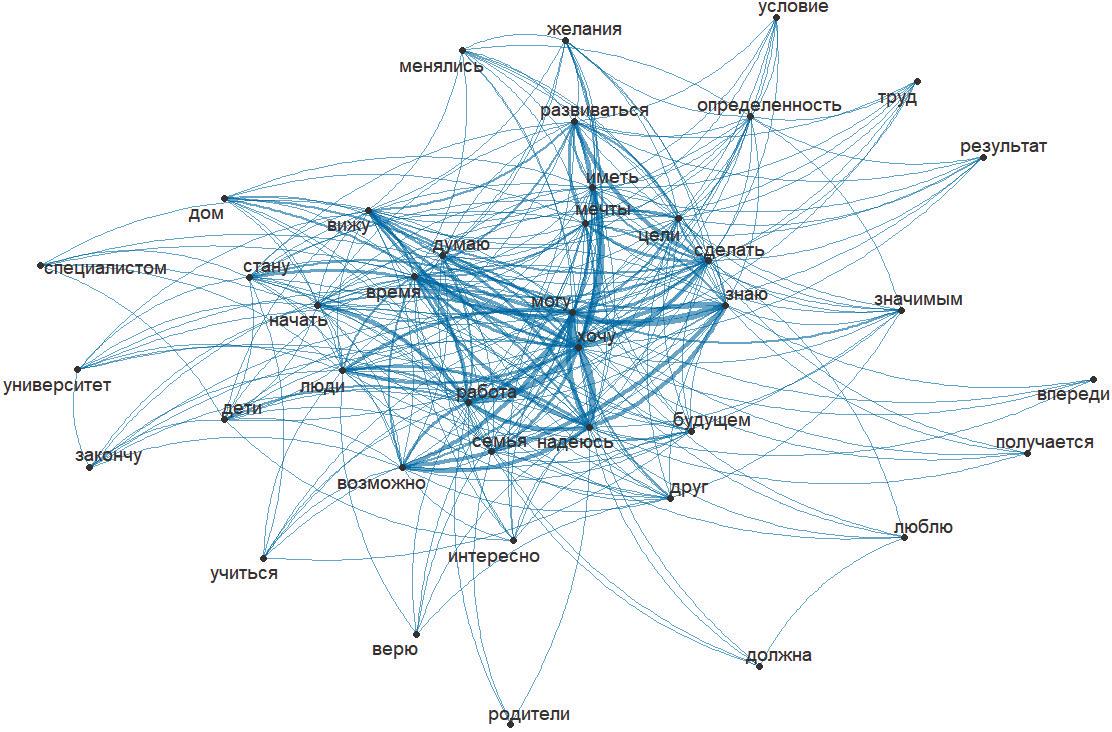

Fig. 3. A dendrogram of the use of words in the description of the future by boys/girls from 15 to 18 years old, constructed using the Ward method (n – 500)

The following significant aspects of the image of the future of 15-18-year-old boys and girls are revealed. The maximum size is a cluster that contains words related to university studies, family – marriage, girlfriend, children, dreams, job, interests, time, etc. Three clusters of approximately the same size are: 1) study is connected with a job, knowledge, the future, amplified by the word "very"; 2) the words "good" "life" and "you" are combined with the words "opportunities" and "person"; 3) the words happy - family, love - to everyone, and another city. A cluster of goals has appeared, in which, among other things, a happy family appears at this stage. The minimum size are two clusters containing one word each: "I hope", "I want". The cluster with the word "hope" has a big difference from the other clusters on the Y axis. This word connects the first and second clusters with the "want" cluster. Fig. 4. A dendrogram of the use of words in the description of the future by young men/women from 19 to 23 years old, constructed using the Ward method (n – 381)

Fig. 4. A dendrogram of the use of words in the description of the future by young men/women from 19 to 23 years old, constructed using the Ward method (n – 381)

The following significant aspects of the image of the future of 19-21-year-old men and women are revealed. The maximum size is the cluster of "achievements", where there is a good job, family values, travel, happiness, goals, a car, etc. The next cluster combined the words "I know", "I can", "I think", "I wanted" with the words "married", "love", "home" and "friend". The two clusters containing one word each ("I hope" and "I want") are of minimal size, by respondents of the age of early youth. Unlike the previous age group, the word "I want" is above the word "I hope" on the Y axis. This word connects all of the clusters , representing the core of the image of the future of young men and girls of late adolescence. Next is a cluster in which work is connected with life, a person and a vision. A cluster appeared that combined the words "time" and "opportunity". Accordingly, the characteristic feature of the image of the future in late youth is the linking of opportunities with time.

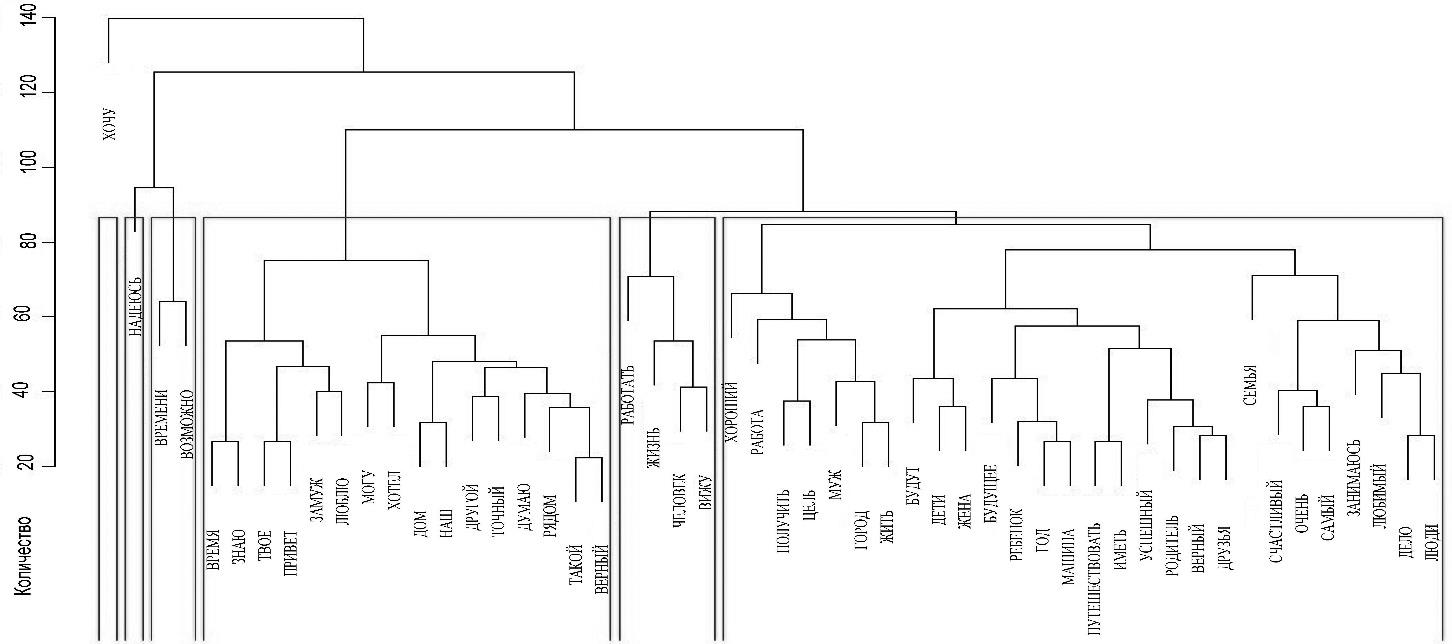

Fig. 5. A dendrogram of the use of words in the description of the future by young men/women from 24 to 28 years old, constructed using the Ward method (n - 383)

The following significant aspects of the image of the future of respondents aged 24-28 are revealed. The maximum size is a cluster with the interrelations of words: friend – to do, city and youth, childhood – great, respect, health and hello, opportunities – success, help, have, speed, wanted – to study, school, future and pleasure, etc. Next, two medium-sized clusters: 1) "life" is associated with the words "want", "can", "will", "developing", "goals", "dreams" and "time", 2) "cluster of hopes", where the word "hope" is associated with the words "home", "good", "our", "everything", "I think", "dream", "beloved". A cluster in which the word "I see" is associated with the words "good", "woman" and "mother" shows the significance of gender role models. In the next two clusters, a job falls into the center, in the verbal expression it is associated with children, happiness and interests, and in the form of a noun with family and addressing yourself in the future. This age group has no "connecting words", and all clusters are connected in meaning and are approximately equally located along the Y axis. Then, using the technique of unfinished sentences of J. Nutten, we investigated ideas about the characteristics of time perspective in age groups from adolescence to adulthood. Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 5. A dendrogram of the use of words in the description of the future by young men/women from 24 to 28 years old, constructed using the Ward method (n - 383)

The following significant aspects of the image of the future of respondents aged 24-28 are revealed. The maximum size is a cluster with the interrelations of words: friend – to do, city and youth, childhood – great, respect, health and hello, opportunities – success, help, have, speed, wanted – to study, school, future and pleasure, etc. Next, two medium-sized clusters: 1) "life" is associated with the words "want", "can", "will", "developing", "goals", "dreams" and "time", 2) "cluster of hopes", where the word "hope" is associated with the words "home", "good", "our", "everything", "I think", "dream", "beloved". A cluster in which the word "I see" is associated with the words "good", "woman" and "mother" shows the significance of gender role models. In the next two clusters, a job falls into the center, in the verbal expression it is associated with children, happiness and interests, and in the form of a noun with family and addressing yourself in the future. This age group has no "connecting words", and all clusters are connected in meaning and are approximately equally located along the Y axis. Then, using the technique of unfinished sentences of J. Nutten, we investigated ideas about the characteristics of time perspective in age groups from adolescence to adulthood. Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of time perspective characteristics (n = 1538)

|

Age |

Mean (number of used) |

Standard deviation |

Standard error |

95% confidence interval for the mean |

||

|

Lower bound |

Upper bound |

|||||

|

Education at school |

||||||

|

14 |

2,34 |

3,07 |

0,36 |

1,63 |

3,06 |

|

|

15-18 |

0,90 |

2,24 |

0,10 |

0,70 |

1,11 |

|

|

19-23 |

0,06 |

0,31 |

0,02 |

0,01 |

0,11 |

|

|

24-28 |

0,03 |

0,16 |

0,02 |

-0,01 |

0,06 |

|

|

Professional education |

||||||

|

14 |

1,11 |

1,79 |

0,21 |

0,69 |

1,53 |

|

|

15-18 |

2,93 |

3,57 |

0,17 |

2,60 |

3,25 |

|

|

19-23 |

1,89 |

3,07 |

0,25 |

1,40 |

2,38 |

|

|

24-28 |

1,54 |

1,62 |

0,18 |

1,17 |

1,90 |

|

|

Professional autonomy (work) |

||||||

|

14 |

2,47 |

4,02 |

0,47 |

1,53 |

3,40 |

|

|

15-18 |

2,22 |

2,75 |

0,13 |

1,97 |

2,47 |

|

|

19-23 |

2,93 |

2,51 |

0,20 |

2,53 |

3,34 |

|

|

24-28 |

3,26 |

3,43 |

0,39 |

2,48 |

4,03 |

|

|

Open present |

||||||

|

14 |

5,25 |

3,17 |

0,37 |

4,51 |

5,99 |

|

|

15-18 |

5,38 |

3,41 |

0,16 |

5,07 |

5,69 |

|

|

19-23 |

4,99 |

2,84 |

0,23 |

4,53 |

5,44 |

|

|

24-28 |

7,00 |

3,41 |

0,39 |

6,23 |

7,77 |

|

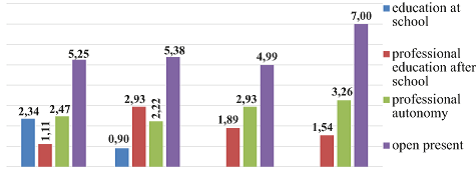

Descriptive statistics show the presence of age differences in the selected characteristics of the time perspective. Changes in the use of time characteristics depending on the age of respondents are shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Age differences in the time perspective characteristics (n = 1538)

Fig. 6. Age differences in the time perspective characteristics (n = 1538)

The period of "education at school" is more often used by teenagers, starting from the age of 15, they talk about it less, it is not used in the two older groups. The period of professional training is more often used by respondents in the age of early youth. "Professional autonomy" is more often mentioned in late youth, and this category becomes even more important at the age of 24-28. The time period of the "open present" is of the greatest importance for the period of the emergence of adulthood. The analysis of variance confirmed these data (Table 2).

Table 2. Variance analysis of differences in the use of time perspective characteristics depending on age (n = 1538)

|

Age |

Time period |

||||

|

Education at school |

Professional education |

Professional autonomy (work) |

Open present |

||

|

14 |

15-18 |

0,000** |

0,000** |

0,912 |

0,989 |

|

19-23 |

0,000** |

0,316 |

0,672 |

0,945 |

|

|

24-28 |

0,000** |

0,843 |

0,345 |

0,006** |

|

|

15-18 |

14 |

0,000** |

0,000** |

0,912 |

0,989 |

|

19-23 |

0,000** |

0,003* |

0,045* |

0,578 |

|

|

24-28 |

0,002* |

0,002* |

0,021* |

0,000** |

|

|

19-23 |

14 |

0,000** |

0,316 |

0,672 |

0,945 |

|

15-18 |

0,000** |

0,003* |

0,045* |

0,578 |

|

|

24-28 |

0,999 |

0,860 |

0,858 |

0,000** |

|

|

24-28 |

14 |

0,000** |

0,843 |

0,345 |

0,006** |

|

15-18 |

0,002* |

0,002* |

0,021* |

0,000** |

|

|

19-23 |

0,999 |

0,860 |

0,858 |

0,000** |

|

Symbols: * p < 0,05, ** p < 0,01

Unlike other age groups, adolescents consider their future using the period of time in their social institution. (F(3;766) = 26.021, p = 0.000), young men/girls of early youth are more likely to use the time interval associated with professional education (F(3;766) = 11,434, p = 0,000). For the representatives of late youth, the most significant is the time interval associated with professional autonomy (F(3;766) = 4,267, p = 0.005). Respondents from the period of the emergence of adulthood more often use time categories that are not limited by time, but are characterized by the metaphor "today and always" (F(3;766) = 6,980, p = 0.000).

Discussion of the results

In this paper, the topic of the changing of the image of the future from adolescence to adulthood is touched upon. Earlier, N.N. Tolstykh pointed out that for young men/women aged 15-18, unlike for teenagers, the period of schooling is less important [Tolstyh, 2015], and N.I. Trubnikova proved that the period of life associated with work becomes the most significant in late adolescence, [Trubnikova, 2010]. Our study significantly supplemented these conclusions. Teenagers really prefer the time interval in their social institution, while young men/women aged 15-18 consider their future in the period associated with professional training, unlike other age groups. Professional autonomy is really important in youth, but for respondents aged 24-28, the time perspective includes categories that are not limited by time and are characterized by the metaphor "today and always". At the same time, our data differs from the conclusions of A. Syrtsova, according to whom the present is most significant for both adolescence and youth, and the future is more important for early adulthood [Syrcova, 2008]. According to our data, at the age of early adulthood, the choice of the type of time categories changes, and instead of periods of social and biological life, time categories are used that relate to the whole life, and not to any specific period. Our results allow us to see the changes that occur at the end of adolescence, during the transition to adulthood, which was not revealed in previous studies. At the beginning of adulthood, according to A. Syrtsova, the skills of managing one's time and choosing goals are acquired, the importance of achieving a set of tasks increases [Syrcova, 2008], as an ideal projection of oneself into the future, motivating personal development [Kostenko, 2006]. Our analysis made it possible to specify age-related changes in the meaningful representation of the image of the semantic future.

The image of the future of 14-year-olds consists of two content clusters: the "cluster of dreams", which contains all the fragmentary ideas about adulthood, and the "cluster of desires", in which "I want" is associated with "opportunities" and a "good" "life", "work" and "person". The remaining clusters are separate connecting words. Their ideas about the future are not formed, and for them the future figuratively speaking "happens", and the impulsivity of adolescents, highlighted by A. Syrtsova, shows not an interest in appearance with a disregard for the inner core [Syrcova, 2008], but rather a lack of understanding of their future as their own adulthood, and conscious work on discussing and shaping their future.

In the image of the future of young men/women aged 15-18, only the words "I hope" and "I want" remain binding, and the largest cluster is still a set of dreams. But in addition to it, three clearly formed separate topics appear, including: professional education, life opportunities and ideas about the family. It is important to take into account the conclusions of Brianza E., Demiray B. about the fact that the frequency of future-oriented statements and words related to family is positively associated with life satisfaction in youth [Brianza, 2019].

In the image of the future of young men/women aged 19-23, the words "I want" and "I hope" remain binding, at the same time the relationship of "time" and "opportunities" appears. Two clusters of approximately equal size appear: the "cluster of opportunities" and the "cluster of achievements". Previous studies have pointed to the links between economic stress, family functioning and psychological well-being [Fonseca, 2020a]. The revealed changes are associated with shifts in the criteria necessary to achieve adulthood, which today depend more on maturity and compliance with norms, rather than on traditional markers such as marriage or work.

The image of the future of respondents aged 24-28 differs from the previous ones in the absence of connecting words, all topics highlighted by this age category have an equal meaning to them , and the two highlighted clusters are associated with a job. Previously, Gunawan W., Creed P.A., Glendon A.I. pointed out that career planning, productivity and satisfaction are associated with assumptions about the possibility of finding a job in the future [Gunawan, 2021], and the opportunity to find a job is associated with professional confidence [Gunawan, 2019]. According to our data, "job" is connected with "family" and oneself in the future, as well as with "children", "happiness" and "interests". But in addition to topics where life plans are set through a vision of employment, the image of the future of respondents of this age includes ideas about "goals", "hopes", "gender roles" and a " future value".

In accordance with this , the question of the sequence of changes in the idea of the future as an understanding of growing up becomes important. The aim of this study was to establish the nature of age-related changes in the image of one's own future in the modern social and cultural situation in the period from adolescence to adulthood.

Main results of the study

As a result of the study, the following conclusions were made about changes in perceptions of the future from adolescence to adulthood:

- Teenagers consider their future using, unlike other age groups, a period of time within their social institution – "schooling". In the ideas of adolescents about the future, there are no clearly defined future directions characteristic of older age groups

- In early youth, the future is considered within the period of professional education. In the image of the future, there is a focus on three topics: professional education, life opportunities and ideas about the family.

- The period of life associated with professional autonomy and a job becomes more significant at the age of late youth. One of the distinctive features of the ideas about the future at the age of late youth is the linking of their capabilities with time.

- At the age of the emergence of adulthood, the categories that are not limited in time, characterized by the metaphor "today and always ", become the most significant in the time perspective. Meaning-forming in the image of the future for them is employment related to children, family, happiness, interests and themselves.

The main limitation of this study is the unequal number of study participants by age. The revealed age differences in ideas about the future from adolescence to adulthood are of fundamental importance for the organization of psychological and pedagogical work with young men/women on issues of professional self-determination. The revealed changes in perceptions of the future are the subject of further research in order to study the dependence of the findings on gender differences.