Introduction

Video games and research

Development of the video game industry has resulted in a rapid transformation of video games, that have evolved from quite simple, allowing for only a limited array of actions, to complex virtual worlds providing multiple choices and paths [Nielsen, 2008]. As a result, in the past few decades video games have turned into a mass medium.

Entertainment Software Association estimates that in the USA more than 227 million people play video games, and 60% of Americans play video games daily. The average age of a video game player is 31. In total, players are roughly half female (45%) and half male (55%). Players agree that video games can bring different people together (89%) and create an accessible experience for people of different abilities (89%) [ESA Entertainment software].

Given the growing popularity of video games, recently there has been a significant increase in the number of research works studying the effects of video games on various aspects of physical and mental development – particularly, in children and adolescents, who represent more than one fourth (around 27%) of the world's gamers [11, с. 25]. Research in this field includes such issues as video game addiction, association between video games and aggression, the influence of video games on higher mental functions (e.g. attention, thinking and memory) as well as on creativity and academic achievement[Ageev, 2023].

Russian research in this area often indicates that Internet addicts and gamers often demonstrate signs of negative psychological characteristics [Kochetkov, 2020; Semikasheva, 2021; Sunnatova, 2019; Sunnatova, 2020]. Interestingly enough, the results of the research are quite controversial. On the one hand, there are scholars who argue that playing video games excessively may result in problems with attention, self-control, aggression and anxiety in children [Gentile, 2011]. On the other hand, certain scholars report on the potential positive impact of video games, their mental health benefits [Granic, 2014], including various specific positive effects [Halbrook, 2019], in particular: decreased reaction times [Worth, 2014] as well as improved performance on visual attention tasks [Granic, 2014] and spatial ability [Greenfield, 1994]. Other reported benefits include improved academic achievement – particularly in maths, reading and science [Kebritchi, 2010; Posso, 2016]. Finally, there is even research to suggest that playing violent video games can help improve social skills by reducing violent behavior among certain populations [Ferguson, 2011].

An interesting area of research is represented by scholars studying the connection between personality and behavior in video games [Quwaider, 2019]. As Borders argues [Borders, 2012], playing video games should be perceived as a conscious activity, which requires a sizeable commitment. According to Hartmann T. and Klimmt C. [Hartmann, 2006], the conscious effort to partake in any kind of behavior is influenced not only by situational constructs, but also by consistent constructs, such as personality. Thus, there are strong grounds to believe that decisions made about video games represent a reflection of personality and its traits. In this regard, contemporary research aimed at studying the possibility of using video games to diagnose cognitive abilities is of great interest [Margolis, 2020].

Studying the association between personality and behaviors in video games is rather challenging both theoretically and methodologically. From the theoretical perspective, one could assume that behaviors in video games resemble very much the player’s real-world behaviors. This implies that users with particular psychological characteristics are more likely to demonstrate in video games certain behavioral patterns than others (e.g. communicative individuals would communicate more than those who are less communicative in real life etc.). However, many video games allow players to emerge into a totally different reality and experience events that are impossible, illegal, or unlikely in the real world [Worth, 2014]. In addition, players’ behaviors in video games are generally free of real-world consequences, which may result in individuals breaking free of habitual behavioral constraints and demonstrating absolutely unexpected patterns of behavior and interaction. Another challenge is connected with giving an interpretation to actions and behaviors that have no direct equivalent in the real life.

From the methodological perspective, research in this area requires adequate tools for examining video game behavior and, more specifically, for revealing the criteria that could be associated with certain traits of personality. It should be taken into account, that given the variety of the existing video games and the diversity of behavioral patterns, which they offer, it may be difficult to generalize the results of research.

It is probably due to this theoretical and methodological complexity that research in this field has been rather limited. There have been several studies examining the association of personality traits and video game behavior in a number of popular video games: “Second Life” - an online virtual world, in which a variety of activities are available [Bayraktar, 2012], the Massively Multiplayer Online Role-playing Game (MMORPG) “World of Warcraft” - a fantasy-type world that allows players to control an avatar [Graham, 2013; Worth, 2014]. These studies have revealed that in-game behaviors and motivations for play are related to personality traits in predictable ways. A few studies of the connections between personality and motivation for playing also suggest that personality-behavior correlations may be found in other video games [Park, 2011], including mobile games [Seok, 2015]. The study by Worth & Book [Worth, 2014] provides a more general overview to the connections between personality and dimensions of behavior in video games.

However, more research is needed to explain why and how people are deeply immersed in certain types of play and what are the factors that influence, predict, and help clarify video game play. The relationship between personality traits and behavior in virtual gaming reality is particularly interesting to investigate.

The current study

The article presents the results of a correlation analysis of the influence of Dota-2 players’ personal characteristics on their behavior in the virtual space. The analysis is based on the data, received in the course of a series of experiments conducted by the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on Contemporary Childhood in Moscow State University of Psychology and Education in 2015-2023 [Rubtsova, 2018]. The aim of the research was to reveal the existing connections between personality traits and behavior in the video game «Dota 2» («Defense of the Ancients 2»). The game was chosen for the empirical research due to a number of circumstances. First, for a certain period of time «Dota 2» was one of the most popular video games among teenagers and young adults (approximately 12,5 million of users around the world.) Second, the game provides access to the history of the sessions, which makes it possible to analyze the gamers' behavior in a longitudinal perspective. Third, the game offers a big variety of roles with different playing functions and capacities. The results presented below refer to the network correlation analysis [Artemenkov, 2021; Artemenkov, 2021a] of the data obtained in the studies.

Methods

Video game “Dota 2” and indicators of play efficiency

“Dota 2” is a multiplayer online battle arena (MOBA) video game. The game was developed as a sequel to the game “Defense of the Ancients” by Valve Corporation. “Dota 2” is played in matches between two teams of five players with each team occupying and defending their own separate basis on the map. Each of the ten players controls a powerful character - a "hero", having unique abilities and a particular style of play. During a match players collect experience points and items for their heroes in order to defeat the other team's heroes in player-versus-player combat. A team wins by being the first to destroy a large structure located on the competing team's basis, called the "Ancient".

The game offers a big variety of roles with different playing functions and capacities (e.g., players can cooperate with each other to defeat difficult game-generated opponents in raids, or attack and kill others’ avatars in player-versus-player activities like battlegrounds).

Valve Corporation provides access to the history of all “Dota 2” matches. Each match is recorded and made available on the website Dotabuff [DOTABUFF. Dota 2, 2022]. Dotabuff is an open-access service collecting raw statistical data of each “Dota 2” match using Steam Web API (application programming interface).

Play behaviors are reflected in numerous indicators that may be used for objective analysis, including:

- frequency of playing and time spent in game (match date and time);

- results of the match (match result: win; lost);

- number of matches abandoned (abandoned match: yes; no);

- number of bot matches played by the player (bot match: yes; no);

- number of playing kills, deaths and assists performed by the player (KDA);

- the hero chosen by the player (hero name; hero role);

- the level of the “skill” developed by the player (normal skill; high skill; very high skill).

An important part of the analysis consisted in considering the choice of heroes by the players throughout the history of matches. For this the following classification of heroes was used [Dota 2 Wiki, 2022]: Carry, Support, Nuker, Disabler, Jungler, Durable, Escape, Pusher, Initiator. In the framework of the research all of the indicators listed above were downloaded and analyzed for 70649 matches.

Procedure and ethics of the study

Participants were recruited through a posting on the site of the Russian social network «VKontakte». In order to be eligible for the study participants were required to have played “Dota 2” at least several times and to be not younger than 14 years of age. A link to the research webpage was provided in the study posting; individuals who were interested in participation could click on the link to enter the project website, where they viewed a consent and information form that explained the purpose and nature of the study. Participants who chose to partake clicked on a link at the bottom of the consent form in order to indicate agreement to start the study.

Taking part in the study required that participants share their profile on Dotabuff webpage [DOTABUFF. Dota 2, 2022]. Each participant who chose to partake inserted the link to their profile on Dotabuff (including Steam ID) into the registration form on the webpage of the research project. Participants then completed the tests. All participants completed the questionnaires in the same order.

Sample characteristics

The participants for the current study were 203 Dota-2 players from Russia, of which 100 participants were excluded because they had failed to fill in all the questionnaires offered in the study. Of the 103 participants included in the analysis, 98 (95.1%) were male.

Participants ranged in age from 14 to 25, with a mean age of 18.3 (SD = 2.9). The majority of participants (79; 76.7%) were under the age of 21.

Frequency of playing video games among participants in the current sample ranged from less than once a month 6 (5.8%) to seven days a week 32 (31.1%). Among 103 participants 34% (35 participants) did not report their frequency, 29.1% (30 participants) reported playing once a week, three times a week or more than 3 times a week. The number of games played by the participants of the study varied from 8 to 8451 matches (M = 1710; SD = 1476) for gaming experience through 1 to 10 years (M = 7.1; SD = 2.8).

Measures

Q-sort technique of W. Stephenson (“Test Q-Sort”)

This technique was developed at the Humboldt University in Berlin and published in 1958. The technique was adapted on the basis of the Research Institute named after V.M. Bekhterev. The stimulus material includes 60 statements, with each of those the subject is asked to agree or disagree. The technique is designed to study a person's ideas about themself and determines tendencies towards dependence and independence, towards sociability and lack of sociability, towards "fight" and avoidance of "fight". The technique also makes it possible to identify the presence of intrapersonal conflicts [Rubtsova, 2021].

Self-Ideal Discrepancy Test (“Test Self-ideal”)

The method of Self-Discrepancy Testing was developed in 1954 by G.M. Butler and G.V. Haigh and makes it possible to determine the features of the modalities of the "I-concept" of the individual. The subjects are asked to evaluate 50 statements with characteristics of the self-image in the range from 1 to 5. The assessment is carried out on the basis of how the subjects see themselves in reality, and then - how they would like to see themselves “ideally”. The diagnostic indicator is the discrepancy between the indicators of "I-real" and "I-ideal" [Rubtsova, 2021].

Inner-Role Conflict Test («Test Roles»)

The questionnaire was developed by O.V. Rubtsova and allows to identify contradictions in the structure of role identity, manifested in such indicators as: rejection of one's own role behavior; rejection of the role behavior of other people; level of need for role-playing experience. The questionnaire consists of 30 statements, with each of those it is proposed to express agreement or disagreement [Rubtsova, 2021].

Adolescent Egocentrism Scale (AES), R. Enright (“Test Enright”)

The AES questionnaire is a classic method for measuring the level of egocentrism. The original questionnaire included 45 questions. A variant containing 60 questions was used (variant of Ryabova T.V., 1997) [Ryabova, 2001].

Additional variables

In addition to the test variables, the age and playing experience of the players in years were also taken into account:

- personal age;

- personal gaming experience (in years).

Results of network correlation analysis

Sample characteristics

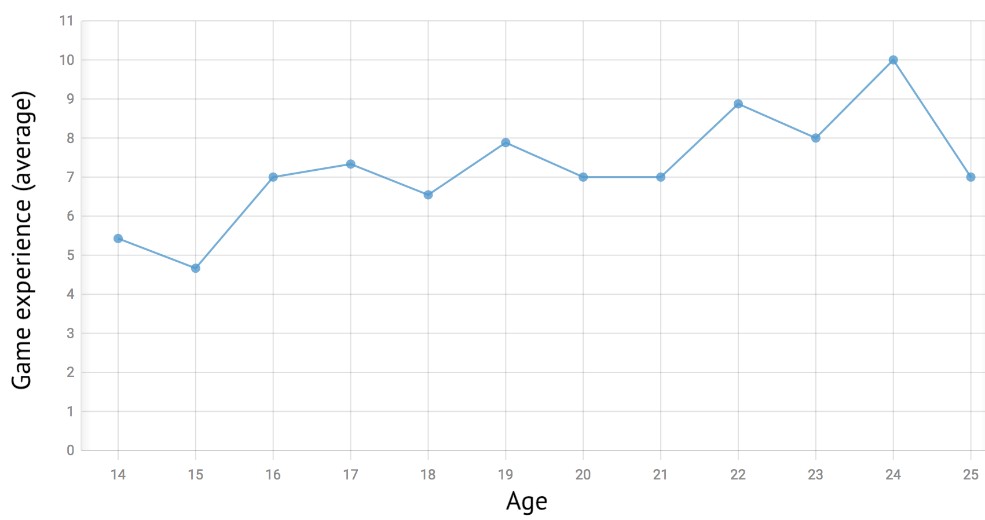

The main results of the study, related to the description of the sample and standard statistical analysis, are published in the article [Rubtsova, 2018]. The number of matches played by players has been shown to increase with a player's age, which is due to the increase in gaming experience with age. Similarly, gaming experience increases with age (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1. Average player game experience for each age scale

Correlation analysis

Designations of personal, psychological and game factors are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Designations of personal, psychological and game factors

|

# |

Symbols |

Factors’ names |

Comments |

|

1 |

AG |

“Player Age” |

Personal age |

|

2 |

GE |

“Player Experience” |

Personal game experience in years |

|

3 |

R1-R5 |

Inner-role Conflict Test (“Test Roles”) |

R1 - rejection of their own role behavior, R2 - rejection of other people's role behavior, R3 - role incompatibility, R4 – role overload, R5 - the need for role experience. |

|

4 |

Q1-Q6 |

Q-sort technique (“Test Q-Sort”) |

Q1 - dependence, Q2 - independence, Q3 – sociability, Q4 – unsociability, Q5 – acceptance of conflict, Q5 - conflict avoidance. |

|

5 |

YA |

Self-ideal discrepancy Test (“Test Self-ideal”) |

The magnitude of the difference between “I-real” and “I-ideal”. |

|

6 |

E1-E6 |

AES, R. Enright (“Test Enright”) |

E1 - personal myth, E2 - imaginary audience, E3 - self focus, E4 - personal interests, E5 - social and political interests, E6 - social and political activity. |

|

7 |

TM |

“Matches Total” |

Number of Total Matches played. |

|

8 |

AK |

“Kill”, “Average Kill” |

The Average number of kills. |

|

9 |

AD |

“Death”, “Average Assist” |

The Average number of deaths. |

|

10 |

AA |

“Assist” |

The Average number of assists. |

|

11 |

AW |

“Win Total” |

Total number of games won. |

|

12 |

AL |

“Lost Total” |

Total number of losing games. |

|

13 |

TA |

“All Total” |

Total number of games played. |

|

14 |

TN |

“Abandon No” |

Total number of not abandoned games. |

|

15 |

TY |

“Abandon Yes” |

Total number of abandoned games. |

|

16 |

T1-T9 |

“Class Total” |

9 game factors of “Total_classificator”. |

|

17 |

1W-9W |

“Class-Wins” |

9 game factors “Wins_classificator”. |

|

18 |

1N-9N |

“Class-Normal-Skill” |

9 game factors “Classificator_normal_skill”. |

|

19 |

1H-9H |

“Class-High-Skill” |

9 game factors “Classificator_high_skill”. |

|

20 |

1V-9V |

“Class-Very-High” |

9 game factors “Classificator_very_high_skill”. |

|

21 |

1U-9U |

“Class-Unknown” |

9 game factors “Classificator_unknown_skill”. |

|

22 |

1B-9B |

“Class-Bot” |

9 game factors “Classificator_bot_match”. |

|

23 |

1S-9S |

“Class-no-Stats” |

9 game factors “Classificator_no_stats”. |

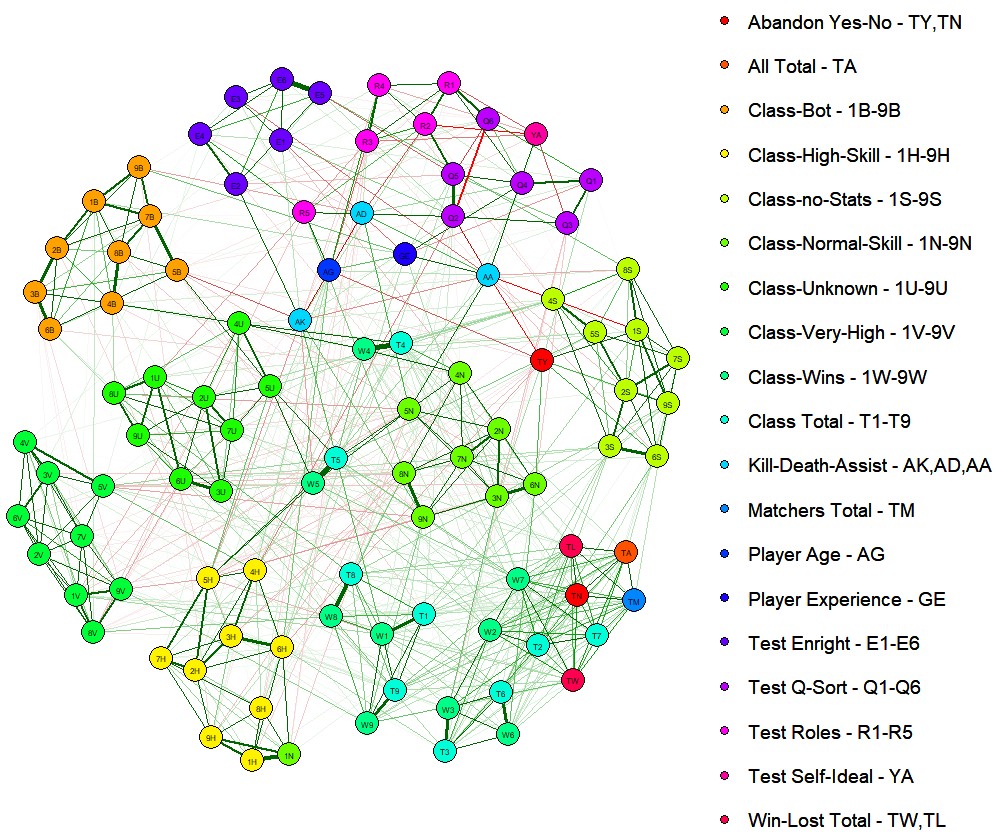

Correlation analysis of 101 measured factors, including personal qualities and “Dota 2” game ratings, was carried out using Spearman's rank correlation and network analysis of partial correlations using the glasso method [2;3]. Mathematical processing was carried out in R with the help of “qgraph” package. Glasso network model of 101 correlated factors is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. A network of partial correlations reflecting the relationships between the studied factors: the age of players AG and game experience GE, personal test characteristics E1-E9, YA, Q1-Q6, R1-R5, and game ratings TY, TN, 1B-9B, 1H-9H, 1S-9S, 1N-9N, 1U-9U, 1V-9V, 1W-9W, AK, AD, AA, TA, T1-T9, TW, TL, TM (parameter λ = 0.1, hyperparameter γ = 0.5)

As Figure 2 shows, factors of different types are grouped and form certain clusters in the network. Clustering is more related to game factors dedicated to game classes and total coefficients. The characteristics of personal psychological testing are also more or less grouped. Meanwhile it is clear that they are not strongly connected with all game rates. Moreover, not all of the links presented in Figure 2 are truly meaningful. A detailed check of the relationship between test factors and game factors showed that only some game indicators have more or less significant correlations with personal and test psychological factors.

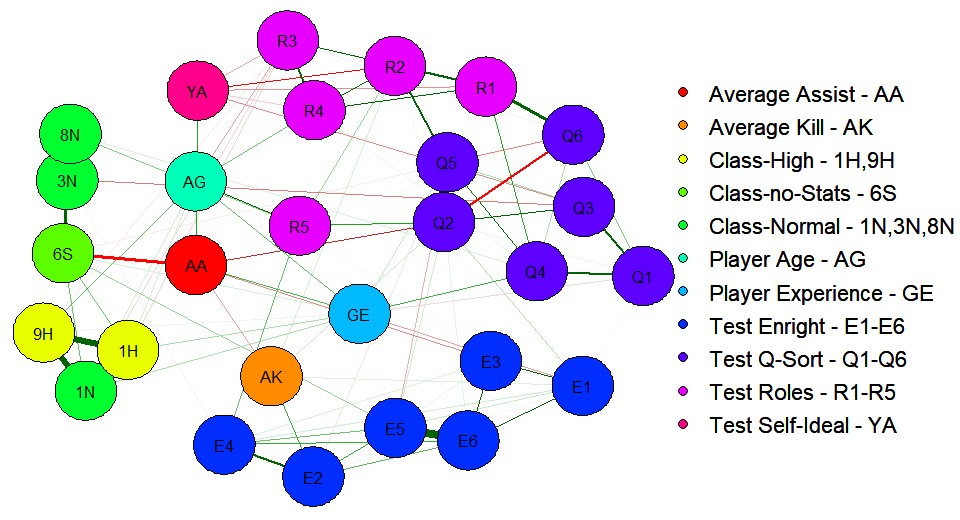

Figure 3 shows a network of partial correlations of 28 factors, showing the relationship of all personal and psychological factors with individual game factors 6S, 1H, 9H, 1N, 3N, 8N, AK, AA. It can be seen that the psychological factors of the tests are associated with a relatively small number of game factors, and these relationships are generally not very strong.

Spearman's significant correlations between game, player, and test factors are shown in Table 2 below. The value of the presented correlations lies in the range: 0.19 < ρ < 0.40.

The age factor AG positively correlates (ρ=0.30**, Table 2) with the psychological factor R5 (role experience). Players with a greater need for role-playing experience tend to be older. The test factor R5 positively correlates with the game factor 8N – class 8 of ordinary abilities (ρ=0.20*, Table 2).

Fig. 3. A network of partial correlations reflecting relationships between 28 studied factors: age of players AG and game experience GE, personal test characteristics E1-E9, YA, Q1-Q6, R1-R5 and game ratings 6S, 1H, 9H, 1N, 3N, 8N, AK, AA (parameter λ = 0.1, hyperparameter γ = 0.01)

The gaming experience factor GE positively correlates (ρ=0.23*, Table 2) with the psychological factor Q4 (non-sociability). Players with more gaming experience are less sociable (apparently, excessive communication distracts from the game). GE gaming experience also contributes to an increase in the average number of players helping other players in the game AA (ρ=0.19*, Table 2). The game is difficult to win without the mutual help of the players in the team.

Factors AG and GE with a high degree of significance (p<0.001) correlate (0.34<ρ<0.44) with the entire group of gaming factors 1N, 1H-9H (the last 9 factors correspond to a high level of gaming skills). The 1N factor is located in the network separately from other medium N-type factors and closer to the group of high H-type factors (Fig. 2) - see the light green node, which is located next to the cluster of yellow nodes. That is why in Fig. 3 factor 1N is located next to the factors 1H and 9H. Almost all of these game factors (1N, 1H, 2H, 6H, 7H, 9H) are significantly (p<0.05) negatively correlated with the R3 factor (0.19<ρ<0.24, Table 2). The 1N factor corresponds to players with normal skills, and the H-type factors correspond to players with high skills. An increase in the values of these factors is associated with a decrease in R3, which means a decrease in the difficulty of combining roles in a group of high skilled players. It should be noted that such dependence is not observed in the group of very high skilled players.

Table 2

Spearman’s correlations between testing and player factors and gaming factors

|

# |

Correlated factors |

Spearman’s correlation |

The rate of significance |

|

1 |

R3-1N |

-0.24 |

p < 0.05 |

|

2 |

R3-1H |

-0.24 |

p < 0.05 |

|

3 |

R3-2H |

-0.19 |

p < 0.05 |

|

4 |

R3-6H |

-0.21 |

p < 0.05 |

|

5 |

R3-7H |

-0.20 |

p < 0.05 |

|

6 |

R3-9H |

-0.23 |

p < 0.05 |

|

7 |

R5-8N |

0.20 |

p < 0.05 |

|

8 |

R5-AG |

0.30 |

p < 0.01 |

|

9 |

Q2-AA |

-0.26 |

p < 0.01 |

|

10 |

Q3-3N |

-0.21 |

p < 0.05 |

|

11 |

YA-AA |

0.25 |

p < 0.01 |

|

12 |

E2-AK |

0.24 |

p < 0.05 |

|

13 |

E3-AA |

-0.20 |

p < 0.05 |

|

14 |

E5-6S |

0.21 |

p < 0.05 |

|

15 |

AG-AA |

0.19 |

p < 0.05 |

|

16 |

AG-1N |

0.40 |

p < 0.001 |

|

17 |

GE-AA |

0.19 |

p < 0.05 |

|

18 |

GE-1N |

0.35 |

p < 0.001 |

|

19 |

GE-6S |

0.21 |

p < 0.05 |

|

20 |

GE-Q4 |

0.23 |

p < 0.05 |

Players who, on average, help more in games, are significantly positively correlated with the YA factor (ρ = 0.25**) and negatively with the Q2 (ρ = -0.26**) and E3 (ρ = -0.20*) factors (Table 2). On the one hand, this suggests that these players are more dependent on other players, and on the other hand, they are less focused on themselves. The psychological factor Q3, which determines sociability, negatively correlates with the gaming factor 3N (ρ = -0.21*).

Players who, on average, kill more during the game, as a rule, have relatively higher E2 scores (ρ=0.24*, Table 2). Apparently, they are more focused on an imaginary rather than a real audience.

The gaming factor 6S has a significant positive correlation with the psychological factor E5, which determines social and political interests, and the gaming experience GE (ρ=0.21*), and at the same time, it negatively correlates with the gaming helping factor AA (ρ = -0.40 ***, Table 2).

It is important to note that the above-mentioned correlations of game factors 1Н, 3Н, 8Н, 1Н, 2Н, 6Н, 7Н, 9Н, 6S with indicators of psychological tests have a relatively low level of significance.

Conclusion

On the basis of correlation analysis, small statistically significant relationships between personal psychological and game factors were revealed. In order to identify other and possibly more significant relationships between gaming and psychological indicators, it seems necessary to increase the sample of subjects.

The possible relationships identified on the basis of correlation analysis show that the need for role-playing experience generally increases with the age of the players. At the same time, players with more gaming experience are less sociable psychologically, but they are more politically interested and ready to help other players in the game. On the one hand, this suggests that these players are more dependent, and on the other hand, that they are less focused on themselves. It is clear that players who help less are more independent and self-centered. Willingness to help is also associated with a greater difference between "I-real" and "I-ideal".

It can also be argued that players with more kills during the game tend to be more focused on an imaginary rather than on a real audience.

The factors of normal and highly skilled players seem to be related to the poor compatibility of these players with the roles that they have to try on in the game. As a result, the difficulty of combining roles is negatively correlated with the level of skill required from the player. In the group of very experienced players, this dependence is not observed.