Introduction

Being, among other things, an attractive resource for improving the results of school education in general, the solution of school failure problems found itself in the focus of multiple domestic and foreign studies. The term “academic failure” was presumably identified in domestic pedagogical science and practice as “academic underperformance”, meaning a student’s habitual educational lag in mastering the content of education. This lag, in turn, caused many side effects, such as a decrease in learning motivation and discipline, an absenteeism or refusal to attend school [Isaev, 2018]. The reasons for this were explained in Russian research tradition mainly by the psycho-physiological, psychological and professional characteristics of the actors of education: failing students, teachers and parents.

On the contrary, in foreign psycho-pedagogical tradition, the main cause of academic failure was explained by socio-economic factors. For instance, the connection between the academic success of students and the socio-economic characteristics of families and their social well-being is deemed as obvious [Bourdieu, 1989].

In the context of the approaches above, special attention has been drawn to cases that stand out of the general logic and involve situations of the failure of psychologically stable students caused by the change in the educational activity context, and, conversely, the examples of the academic success of learners that stay in unfavourable conditions. The undertaken comprehensive pedagogical and psycho-pedagogical studies of academic failure, which explored the relationship between external educational conditions (in relation to the learner) and his/her internal (personal) state, made it possible to assume the connection of academic failures with personal resilience [6].

The concept of “personal resilience” is still interpreted ambiguously in modern science. The theoretical analysis of “resilience” as a concept, performed by Selivanova, Bystrova, Derech, Mamontova, Panfilova, led these researchers to the conclusion that both domestic and foreign scientists consider it as viability and vitality at the same time [5]. In particular, Makhnach is of the opinion that the English-language term “resilience” (flexibility, tenacity, elasticity, resistance to external influence) would be more correctly applied in the Russian language as a synonym for the word “viability” – i.e. personal resilience means the ability to stay alive, to preserve one’s life, to exist and develop, of being adapted to life [8]. This opinion is confirmed in the work by Valieva who states that resilience is the ability for quick adaption in unpredictable and difficult life situations [1, p. 97]. S. Maddi writes that the path to viability (in this context – resilience) is a vital capacity which increases the potential for viability in difficult circumstances [26]. In addition to “personal resilience”, pedagogical studies actively discuss the phenomenon of “academic resilience” that means the ability of a learner or an educational organisation to demonstrate high academic results in difficult circumstances [4, p. 36].

In spite of their abundance, the studies of resilience so far do not let one unambiguously answer the questions on the relationship between students’ personal resilience and their academic success; on the impact of the dominant style of pedagogical interaction practiced at school on resilience; on the orientation of the teaching and learning processes at the achieving of educational results or towards a demonstration of the indicators of academic freedom provided to students, along with a number of other factors. The answer to these questions determines the possibility of an efficient introduction of the results of theoretical research into educational practice [2; 8].

The set of pressing issues that touch upon various aspects of resilience as a personal phenomenon that has organisational and pedagogical support makes relevant the need for a comprehensive study aimed at identifying the most common and explicit dependencies of personal resilience to the diverse characteristics of the educational process. Obviously, research of this kind is quite extensive, cannot be carried out simultaneously and requires a sequence of exploratory studies represented, among others, by the present essay.

According to its goals, the research can be classified as a pilot study. Its first stage concerned a primary search of dependencies and was carried out using a simplified programme based on the cluster analysis of relationships. At the same time, the study also included a more serious analysis of interrelations (based on correlation analysis), which made it possible to draw more in-depth conclusions on its grounds.

Key Research Questions:

1) How is personal resilience related to the learner’s other characteristics and his/her academic success?

2) What characteristics of the educational process influence the learner’s personal resilience and academic success?

The methodological basis for the quantitative and qualitative analysis of the research findings was as follows:

1) the concept of the unity of politics and nature [Latour, 2004; Latour] that turned the authors to the consideration of various situations related to the disturbance of the psychological and social balance of schoolchildren, with regard to the variety of their internal and external interrelations and interdependence. From these positions, the phenomenon of student’s personal resilience is interpreted as a characteristic of the process of revision of his/her relations with the elements of the significant environment in a non-equilibrium situation towards ensuring its sustainability.

2) the synergetic approach [21; 22; 23] to the analysis of developmental processes, asserting the openness of the system to be its main condition. In accordance with this approach, a student’s personal resilience, as a characteristic of the sustainability of his/her development, should be ensured by his/her vigorous interaction with various education actors in a broad sense.

3) the activity approach [3; 20] to the organisation of educational process, focusing on the leading role of activity in the formation of schoolchildren’s personal qualities.

The above approaches cover in the aggregate the main problem areas of research in the field of resilience and make it possible to consider it from the perspective of the unity of teachers, students and the educational organisation treated as interrelated and, at the same time, independent subjects of consolidated educational activity that integrates a multitude of separate actions. This, in turn, makes it possible to identify, on the basis of the quantitative and qualitative analysis of the research findings, the most significant factors of personal resilience development in schoolchildren in the context of their academic success/failure.

The survey sample comprised 791 students from 8 general education organisations representing 2 municipal districts of the Republic of Tatarstan. After culling, 722 questionnaires were admitted for further processing, which secured the due level of the statistical reliability of the obtained results.

The survey involved 5th-9th grade schoolchildren; the sample frame selection method was random sampling. The use of a more complex sample frame estimation method, with regard for the objectives of the study, was not required.

Methods. The survey was based on a specially designed questionnaire that included a module for assessing personal resilience, a module for assessing a set of characteristics of the educational process, potentially relevant for personal resilience and learners’ academic success, a module for assessing deception in answering, and hard data.

The module for assessing personal resilience was developed on the basis of the “Brief resilience scale” method [Smith, 2008]. Testing the module for internal consistency of the characteristics describing personal resilience, with the use of standardised Cronbach alpha coefficient (independently of the other modules), showed the result αst =0.927. The module included six statements offered for evaluation by the students on a 10-point scale. Three of them characterised a pupil as resilient and three – as non-resilient. To evaluate personal resilience, an integral coefficient was calculated as a ratio of resilience to non-resilience. The respondents with the coefficient above being equal to three or higher were referred to as the cluster of learners possessing due resilience.

The module assessing educational process made it possible to evaluate the emotional attitude towards learning, the level of pupils’ academic independence and activity, their disposition to help on the part of teachers, parents and friends in a problem situation, their preferred style of learning interaction, plans for the future, as well as the level of self-esteem towards learning achievement.

The module assessing deception included mutually exclusive answer options and, on the conversely, identical response options. Depending on the received answers, a conclusion was made on the extent of risk of the pupil’s inattentive completion of the questionnaire and his/her admission to further processing.

Additionally, the study involved the method of focused interviews with the heads of educational organizations who took part in the study. The method was used to obtain the necessary clarifications to explain the identified dependencies.

Discussion. At the first stage of the research findings analysis, the authors engaged in the clustering of the surveyed schoolchildren on the basis of “personal resilience” and compared the characteristics of the outlined clusters. A total of 42.8% of the respondents turned out to be resilient. The comparison of answers by pupils representing “resilient” and “non-resilient” clusters showed the following results (Table 1).

The resilient pupils were characterised by more vivid emotional attitude towards learning. Most of them said they definitely “liked learning” (33.3% vs. 14.3%), but a significant share of the respondents definitely “disliked learning” (16.7% vs. 3.1%). Less than one per cent of resilient learners found it difficult to answer the question about their attitude to studying, while the respective number among the non-resilient pupils was 15.2%.

Table 1. The Most Significant Differences between Resilient and Non-resilient Learners*

|

Variable parameter |

Resilient (%) |

Non-resilient (%) |

|

They like to learn |

33.3 |

14.3 |

|

They do not like to learn |

16.7 |

3.1 |

|

They do not tend to turn to anyone for help |

67.0 |

13.7 |

|

Academic independence |

71.3 |

29.9 |

|

The teacher explains how one can work out independently |

17.1 |

6.1 |

|

The teacher tries to help right away |

7.9 |

85.7 |

|

The parents are always responsive to requests |

31.9 |

68.3 |

|

The parents handle only a small share of requests |

37.7 |

7.1 |

|

They are orientated towards continuing their education |

68.7 |

34.9 |

|

They are orientated towards getting a job |

16.8 |

14.3 |

|

They attend an elective course, study group or club |

50.1 |

63.9 |

|

They think they can learn better |

35.4 |

64.3 |

|

Academic performance |

score 4.17 |

score 3.96 |

* The probability of null hypothesis on random nature of differences is H<5%

The resilient schoolchildren are more independent in solving arising problems. A total of 67.0% of them are not inclined to turn to anyone for help – “these are my problems”. The corresponding share of the non-resilient schoolchildren is 13.7%.

Similar differences are observed with respect to academic independence. The statement “If the teacher does not control the students, they will be inactive” is generally rejected by 71.3% of the resilient pupils against 29.9% of the non-resilient ones. Those who disagreed principally constituted a share of 2.8% and 6.5% respectively.

In the case of appealing to a teacher for help in working with the learning material, the help options also differed for the analysed groups. As for the resilient pupils, the teacher “Explains how I can sort out the material on my own” almost three times more often (17.1% vs. 6.1%). As for the non-resilient ones, the teacher more often “Tries to help immediately if he/she has time” (85.7%) or even “Finds time for an additional class” (7.9%). The share of such options for the resilient pupils is 49.9% and 1.6%, respectively.

The parents help resilient schoolchildren in their studies to a significantly lesser extent as well. Answering the corresponding question, the option “The parents always respond to my requests” was checked by 31.9% of the resilient pupils and by 68.3% of the non-resilient schoolchildren; and on the contrary, the option “The parents handle only a small share of my requests” was marked by 37.7% and 7.1% respectively. To the parents’ credit, it should be noted that the option “The parents can never help me” was checked by only 2.5% of the surveyed schoolchildren.

The obtained data generally agrees with the results of the survey by Kosaretsky, Mertsalova and Senina which shows that parents of the least performing children note more often the lack of the school’s attention to pupils’ learning problems, while teachers working at schools with a high proportion of failing children demonstrate a low level of responsibility for the academic success of pupils [Kosaretskii, 2021].

The majority of resilient learners are more oriented towards continuing their studies at higher educational establishments (68.7% vs. 34.9%), which is quite natural, given their higher academic performance on the average (score 4.17 vs. 3.96). However, the number of those oriented to “start working” is also higher among resilient learners (16.8% vs. 14.3%), which is evident of heterogeneity of the “resilient” group. This is also evidenced by a fairly even distribution of resilient learners in terms of the need to stay at an extended day group at school. Although the “I doubt it, but why not?” answer option was the most popular (31.7% of all responses), all other response options, from definitely positive to unambiguously negative, scored approximately 16% with minor deviation. The group of non-resilient schoolchildren did not show such unanimity.

The non-resilient students proved to be more active when in concern to additional education. A total of 63.9% of them attended some elective course or a club/section. The respective share among resilient learners was slightly more than half – 50.1%.

Non-resilient schoolchildren also are more optimistic about their ability to learn better. A total of 64.3% of them noted that they “could learn much better”, and 28.6% – that “generally, they could learn better, but not really by much”. The respective proportion among resilient pupils was 35.4% and 48.9%.

The differences between the analysed groups in terms of preferred interaction style (autocratic, democratic, liberal) and learning orientation (formal indicators or formed competences) proved to be statistically insignificant.

The generalization of cluster analysis results points towards the presence of statistically reliable differences between the explored groups of schoolchildren in the above-considered parameters and, at the same time, towards significant internal differences. In particular, despite the predominantly higher academic performance of resilient schoolchildren this cluster also includes stable low-performers, the same way that one can see quite successful pupils in the cluster of non-resilient students.

In order to clarify the specific features of resilient learners and the educational process characteristics that influence personal resilience, a correlation analysis of the results was carried out. When preparing the study, the authors hypothetically assumed, relying on multiple publications, that a learner characterized by a stronger personal resilience has the following features: a higher learning motivation (likes to study) and demonstrates higher academic performance; resorts to help of the parents, class teacher, teachers and schoolmates in solving his/her problems; is inclined to the democratic style of educational interaction; is focused on the formation of personal competencies, not formal indicators of his/her efficiency; is independent in studies and does not need the teacher’s control; is orientated towards continuing his/her studies at a university; does not need to stay at extended day group; attends some elective, workshop or special classes; is confident that he/she can learn even better. As a result, an attractive image was formed – of a person who is resilient towards life difficulties, is able to actively use the resources provided by the personal environment in order to overcome any obstacles effectively. However, not all of these assumptions were confirmed during the course of the correlation analysis.

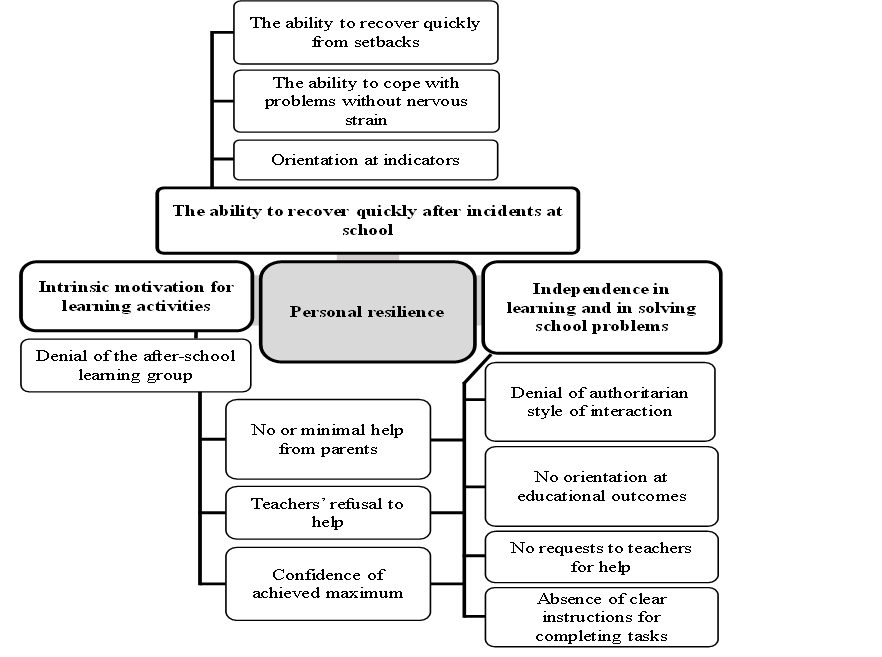

Based on the revealed significant correlations (p<0.05), the following model of the personal resilience of schoolchildren was observed (Fig. 1).

When speaking of the most important characteristics of personal resilience, it is necessary, firstly, to note the autonomy of a resilient learner, which largely contradicts the initial assumptions on one’s orientation to help of his/her immediate environment and the ability to use it effectively. This said autonomy is determined by the following groups of objective and subjective factors/features:

1. Self-dependence in learning and in solving school problems – two aspects of the general personal independence of schoolchildren – overlapping, but not identical – objectively it is conditioned by the absence or the minimal meaningful help in studies from the parents, as well as problems with help on the part of the teachers.

Resilient pupils do not seek help from anyone in case of any problems at school (not only academic ones) – not from the class teacher nor from other teachers, nor from the parents/relatives, not even from their friends – “I will not turn to anyone – these are my problems”.

Independence in resolving school problems, like academic independence, correlates with schoolchildren’s confidence in the achieved maximum of their own educational resources. However, in this case, this confidence is manifested against the background of the denial of one’s real educational results in favour of formal indicators. Objectively, this type of independence is “supported” by the lack of clear instructions from the teachers on the performing of learning assignments, against the backdrop of children’s unwillingness to appeal for help. Considering that, talking of academic independence, this was associated with “teacher refusal”, one should realise that independence in solving school problems correlating with “no appeals” can be considered an extreme expression of general personal independence and can be evident of the formed attitude towards a “non-cooperation” with teachers. A.S. Fomichenko in her research addresses the role of the emotional support of pupils and guidance of their academic achievements. She substantiates the relevance of the assumption that the relationship between the teacher and the learners is a significant motivational factor affecting schoolchildren’s academic performance [Fomichenko, 2017]. She also explores thoroughly the effect of teachers’ expectations on learner performance.

In general, the correlation analysis results confirm the preliminary conclusions drawn on the basis of cluster analysis. It should be recognised that the outlined correlations point at significant problems in the organisation of the educational process, and, as a result, at schoolchildren’s actualised need to rely on their own resources in solving educational and extracurricular problems. The latter obviously is an important factor (among other conditions) in the formation of resilience as the ability to maintain a personal stability contrary to circumstances.

The mentioned correlations confirm that providing pupils with the possible maximum, a pedagogically justified academic freedom (both on the part of the teachers and parents) is a key factor in the formation of their academic independence. Incidentally, this approach is fully consistent with the requirements of personality-oriented education [17] and the guidelines of modern educational standards.

2. Internal motivation of learning activity manifested in the denial of the teacher’s control – as a leading condition of students’ academic activity; this group naturally denies the need for an extended day group as a form of additional help in the solution of academic problems. Given that the presence of such a group can act as a serious mechanism compensating for a negative contextual influence, the indicated correlation seems to be important. In other respects, correlation analysis showed the same significant dependencies as those observed in relation to learners’ independence: the development of pupils’ intrinsic learning motivation can be facilitated by no help or by minimal assistance on the part of teachers and parents. Also, a developed internal motivation is accompanied by the learners’ confidence that they cannot learn better than they do now.

3. The ability to recover quickly after various incidents at school – this, according to correlation analysis, is the most significant component of personal resilience. The presence of significant correlations between the described ability and the ability to quickly recover from quarrels and troubles, as well as to cope with problems without unnecessary worries, testifies to its system-forming role in a set of personal resilience indicators. However, of special attention is the correlation of this ability with the learner’s orientation at high academic performance indicators (Unified State Examination, high grades, an impressive portfolio) rather than educational results (the due-quality performance of educational tasks, the maximum assimilation of learning topics, their correlation with personal experience).

Since the learners’ revealed orientation contradicted the authors’ initial assumption on the preference of their own competencies rather than of formal indicators of efficiency by resilient pupils, a focused interview with the heads of relevant educational organizations was undertaken in order to find out the reasons for this state of affairs. The interview yielded expected results, confirming that all educators, without exception, used the managerial method based on key performance indicators. At the same time, the main KPIs rest on results of the Basic State Examination, the Unified State Examination, All-Russian test papers, school victories in competitions/olympiads of various levels as well as some derived indicators that position the school within the municipal education system. The corresponding attitudes are transmitted by teachers to learners, which in turn shapes the higher stability of those who accept the “rules of the game” to a due extent.

Fig. 1. Model of Schoolchildren’s Personal Resilience

Fig. 1. Model of Schoolchildren’s Personal Resilience

Table 2. Significance of Correlations between Personal Resilience Constituents

|

|

P |

|

P* |

|

|

Personal resilience

|

0,000 |

Ability to quickly recover after school incidents |

0,006 |

Ability to quickly recover from accidents |

|

0,029 |

Ability to tackle problems without worrying |

|||

|

0,030 |

Focus on the performance indicators |

|||

|

0,006 |

Independence in learning and in solving school problems |

0,001 |

Denial of the authoritarian manner of interaction |

|

|

0,009 |

Lack of focus on the educational outcome |

|||

|

0,006 |

Absence of support requests to teachers |

|||

|

0,022 |

Lack of precise instructions for the implementation of tasks |

|||

|

0,002 |

Intrinsic motivation to study |

0,000 |

Denial of the extended-day groups |

|

|

0,000 |

Absence or minimal help from parents |

|||

|

0,002 |

Refusals to help from teachers |

|||

|

0,000 |

Confidence in the accomplished maximum |

* P-value (2-sided)

The presence of both high performing learners and low performers among resilient pupils actualised the issue of the associated factors of academic success/failure. In order to identify them, the authors identified two respective clusters of learners. The poor performers were those who demonstrated a grade point average of 3.5 or less during the past year, and the high performers were those who had a grade point average above 3.5. The results of the correlation analysis held within the clusters, with a further comparison of the findings, showed the presence of statistically significant differences in the academic success of the outlined groups of schoolchildren.

Both groups of pupils improve their academic performance if they feel in the process of learning “that they now know more than before” and that “they have not lived this day in vain, having achieved something”. In addition, efficient pupils have social motivation added to intellectual and meaning-based motivations – “classmates, teachers and parents recognise my success and respect me more”. Material incentives (“they buy me good things”) and psychoemotional stimuli (“everyone praises me”) in both cases do not provide the expected result in the form of a steady improvement of academic performance.

The meaning of educational activity for low performing and high performing schoolchildren also differs. The academic performance in the low performers cluster correlates exclusively with an understanding of the fact that the future depends “on how I study today, whether I will have a worthy place in the society”. The correlation range for high performers is much broader. Statistically significant correlations in this case show the dependence of one’s academic performance on the understanding of its coherence, in addition to the social position with “material wellbeing”, the possibility to engage in “intellectual labour” in the future, “to do something worthy in life, to be of a high benefit to people”.

The achievements of low performers correlate exclusively with a certain type of learning activity in class and when doing homework – aimed at memorisation: “reading, memorising texts and definitions”. The correlations for high achievers are much richer. In addition to the orientation on the acquisition of knowledge, learning efficiency is determined by the urge for understanding (“I explain why this is so and not otherwise”), practical application (“I apply acquired knowledge for solving new challenges”), analysis (“I single out the most important of what I have learnt; I reveal the logic of the interrelation of the parts and the whole”) and synthesis (“I conclude how new knowledge is connected with what I already know; I prepare presentations, essays”).

High performing pupils view academic achievement as correlating with the fact that they “always get an assessment of what they do”. At the same time, the assessment “always corresponds to academic achievements”, and pupils are “always satisfied with their academic results”. The above-mentioned dependencies are not traced for low performers; however, the improvement of their academic success correlates with “receiving individual assignments in class and for homework”. The common feature for all pupils is the dependence of their success on the “extent their assignments match their interests and abilities”.

Thus, the undertaken analysis makes it possible to state that, in general, while the success of resilient pupils is higher, the differences among them in terms of academic success/failure are conditioned by the differing degree of their involvement in the educational process under the influence of both internal and external factors. The internal reasons for resilient learners’ success include a deeper understanding of the meaning of education and its impact on life prospects. The external factors include the impact of academic performance on the learner’s sociometric status, the diversity of educational activities and their goals, the extent to which educational assignments match the learner’s individual characteristics, the adequacy of the evaluation of their fulfilment.

Taking into account that the same group of resilient learners included the pupils differing in academic performance, attitude to studies, as well as the nature of interaction with other educational activity actors, it is logical to assume that the high degree of resilience towards the problem situations that unites them has different grounds. This not only explains the absence of statistically confirmed correlations, but also points to the existence of different “individual styles” of resilience. These styles represent a more or less coherent set of methods (forms, tools and methods) used by the learners to return to a temporarily lost equilibrium – from the urge to meet the teachers’ requirements to a maximum extent to, conversely, manifestations of protest against them.

The difference in individual resilience styles, in turn, allows one to assume the presence of a certain “equilibrium point” in a learner as the basis of the above – as a complex of the most significant subjective values that determine the learner’s evaluation of the context of their own activities and self-assessment in some given circumstances. The pupil’s state matching the indicated values is perceived by him/her as comfortable, and it motivates the pupil to return to the “equilibrium point” in case of a violation of the equilibrium state. Obviously, learners differ significantly from each other on this basis. For instance, a “satisfactory” rating is quite comfortable for some pupils, while for others it is critically low.

Similarly, the individual differences of resilient learners will manifest themselves in relation to an educational activity context perceived by them as a deviation from some norm. If, for instance, rudeness on the part of an adult can permanently bring one learner out of balance, this attitude can be perceived by another pupil as a quite familiar pattern.

Undoubtedly, these hypotheses require additional research for their scientific substantiation. At the same time, being based on the fundamental provisions of the science on individuals’ differing subjective reactions to comparable objective impacts, and on the internal changes being influenced by external factors, the proposed hypotheses might be deemed to be viable.

Conclusions:

- Personal resilience, as a learner’s ability to quickly recover from various incidents at school, to recover after quarrels and troubles, to cope with challenging (academic and extracurricular) circumstances without excessive nervous strain, may have different manifestations in similar conditions, which requires a differentiated approach to its analysis and targeted formation.

- Resilient students differ from non-resilient ones by a range of features, including a more emotional attitude towards learning, independence in solving arising problems in life and at school; they are more orientated towards continuing their education; the number of high achievers among them is higher. Non-resilient learners are more active in terms of additional education, more optimistic about their ability to study better. However, in case of pronounced differences between the surveyed groups of learners, it would be premature to assert their personal resilience as a basis for academic success or to consider resilience as a certain system-forming quality of the individual which forms a space of unambiguously positive attending qualities.

- With a pronounced similarity in terms of “resilience”, the surveyed groups of learners are quite heterogeneous in their characteristics, which is reflected in weak correlations between resilience and certain characteristics of schoolchildren. This can be explained by the difference in learners’ “resilience styles”, accounted for by the individuality of their states perceived as “comfortable”, as well as the individual perception of the context of their activities and the difference in the ways used to return to the initial state after being forced to leave it. At the same time, correlation analysis results suggest that the key feature of a resilient learner is his/her autonomy, manifested in: 1) the independence in solving academic and other school problems as a reaction to the absence or insufficiency of meaningful help from parents and teachers, and 2) an expressed intrinsic motivation for learning shown through the students’ rejection of teacher control as a major condition of academic activity.

- The differences in resilient pupils’ academic success/failure are caused by their differing involvement in the educational process under the influence of internal and external factors (the former – an increased awareness of the purpose/importance of education and its influence on life prospects; the latter – the influence of academic achievements on the pupil’s sociometric status, the diversity of educational activities and their goals, compliance of educational assignments with the learners’ individual characteristics and adequacy in the evaluation of their performance).

- The formation of personal resilience in students is principally influenced by the frequently arising need to solve their problems independently, as well as by the variety of educational interaction styles offered by the teachers that makes the pupils continually adapt to changing conditions. At the same time, the nature of resilience is determined by educational traditions dominating the school and its target orientations.