Introduction

The changes taking place in society and in education have affected the requirements for teaching staff. The implementation of the 21st century teacher model involves the formation of a highly professional, competent, creatively active personality with a dominance of spiritual and moral qualities [Rubcov, 2010]. In solving this problem, the institution of mentoring is of utmost importance.

Mentoring is a historically popular and proven mechanism for young specialists to enter professional activities, an effective tool for their accompaniment and support, development of their competence, and one of the ways to master and transmit innovative teaching practices [Dey, 2021]. The growth of research and practical interest in mentoring problems is facilitated by the work to create a methodology for a targeted mentoring model within the framework of the federal projects “Modern School”, “Young Professionals”, “The Success of Every Child”, which consider mentoring in a broad social context [Medvedev, 2022; Montgomery, 2022].

The organization of mentoring in a modern school faces a number of problems. Firstly, the effectiveness of accompaniment and support of a novice teacher by a teacher-mentor is difficult to measure and is not obvious due to the difficulty of differentiating and assessing the contribution of the mentor and mentee to the professional development of a novice teacher [Loesch, 2023]. Secondly, young specialists are not always ready to follow the recommendations of senior colleagues, and not every experienced teacher is ready and able to share professional experience, including due to its insufficient comprehension and systematization [Tay, 2021]. Finally, successful mentoring practices do not always become the subject of research, study, mass dissemination and adoption [Aparicio-Molina].

The above actualizes research on mentoring as a tool for managing the professional development of teachers [Meutstege, 2023].

Methodology and methods

Models of professional development of a teacher and the actualization of his creative potential are analyzed in the works of T.V. Gavrutenko [Gavrutenko, 2022], M.V. Druzhinina, A.N. Zagorodnyuk, T.V. Kudryavtseva, Ya.A. Ponomareva, I.V. Strakhov. The essential characteristics and structure of mentoring as an effective tool for professional development are described in the works of E.A. Dudina [Dudina, 2017], L.A. Mokretsova, N.V. Sharapova, a number of foreign authors [Cassels, 2018; Drew, 2014]. Ways of forming teachers’ motivation for professional development and self-development, stimulating their pedagogical creativity in the context of mentoring activities are studied by A.N. Bubnova, O.G. Davydova, I.L. Pronkina, N.Yu. Sinyagina.

Theoretical models of mentorship are presented in the works of S.G. Antipina [Antipin, 2011], N.A. Bykova, T.V. Dyachkova, S.I. Pozdeeva, A.Yu. Pomogaibina, Yu.A. Snegireva, M.A. Fedulova, E.I. Chuchkalova and others. Issues of managing the development of mentoring at school are explored in the articles by Yu.V. Gavrusheva [Gavrusheva, 2021], N.P. Ivanova, M.E. Ledovskoy, I.V. Rozdolskaya and others. The works of S.A. are devoted to mentoring as activity support for young teachers. Barkova, N.L. Myslivets, S.I. Pozdeeva [Pozdeeva, 2017], S.N. Shcherbinina and others.

In the domestic literature, mentoring is predominantly viewed as:

- instrument for creating sustainable motivation for self-development [Blinov, 2019; Ilaltdinova, 2016; Janesko, 2020];

- effective means of entering the profession [Palitaj, 2019; Qin, 2023];

- method of professional socialization [Kashaev, 2022; Wibowo, 2022];

- mechanism for supporting the professional growth of a young teacher [Muhametzjanova, 2020; Fedorov, 2021];

- technology of subject-subject interaction in the professional and pedagogical community [Vaganova, 2022; Ladilova, 2022; Brandisauskiene, 2020];

- synergetic system of self-organization and self-realization of subjects of educational activities [Kuznecov, 2023; Sebel'dina, 2020; Wright, 2018].

Foreign authors (G. Lewis, D. Megginson, L. Rai, etc.) correlate mentoring with human resource management activities. Thus, L. Rai defines mentoring as “the most successful method of skill transfer” [Raj, 2002]. Mentoring according to G. Lewis is “a system of relationships for the purpose of gaining experience in the workplace” [L'juis, 2002]. D. Megginson considers mentoring as a way to assist an employee in building his professional career, adequately assessing his capabilities and mobilizing existing potential [Chelnokova, 2018], D. Clutterbuck speaks of “combining the role of a parent and peer, consulting, coaching and facilitation by a mentor” [Clutterbuck].

Foreign experience in organizing mentoring is associated with the search for effective ways to transfer experience and skills within the framework of a specially formed support system for a young specialist, called “mentoring”, the main principles of which are the authority of the mentor, mutual trust and equality of the mentor and the mentee, a friendly atmosphere, and interested participation. In this interpretation, mentoring tasks are formulated as:

- facilitation of a young teacher’s entry into the professional environment;

- ensuring the teacher’s socialization in a new environment;

- support and consolidation of successful experience;

- encouraging all participants in the process to interact creatively [Margolis, 2019; Meyer, 2017].

Both Russian and foreign researchers agree in recognizing the importance of the problem of motivation for mentoring activities of both the mentor and the mentee. The analysis of publications on this topic showed that the greatest interest is in issues of understanding and recognizing the importance of mentoring, attitudes towards it, and the formation of appropriate behavior patterns. The results of studying the works of Russian and foreign researchers suggest that the frequently mentioned motivations for mentoring include (Table 1):

Table 1. Typology of motives for mentoring activities *

|

№ |

Name of the motive |

Content |

|

1. |

Need for self-realization and recognition |

The desire to acquire a certain social status, professional and public recognition, increasing satisfaction with the results of one’s own work |

|

2. |

Need for authentication with a significant person |

The desire to be like an authoritative person, gaining and strengthening personal authority |

|

3. |

Need for leadership (authority) |

The desire to occupy a leadership position, expand power, gain the opportunity to influence the activities of other people, control and evaluate their actions and actions |

|

4. |

Need for activity |

The desire for more active participation in the processes of the organization, socially significant activities, and an increase in contribution to the overall result |

|

5. |

Need for positive reinforcement |

The desire to receive benefits determined by the position (prestige, material incentives, benefits, etc.) |

|

6. |

Need for self-improvement |

The desire to improve one’s own competence, professional growth, and mastery |

|

7. |

Need for success |

The desire to achieve significant performance results, leadership, and setting ambitious goals |

|

8. |

Need to avoid failure |

The desire to avoid causing displeasure and criticism from management, to avoid punishment, deprivation of privileges, etc. |

|

9. |

Need for communication and emotional contacts |

The desire to establish and maintain constructive relationships with other people and interpersonal interaction |

|

10. |

Sense of duty and responsibility |

The desire to conscientiously carry out assigned work, perfectionism, and a high level of social responsibility |

Legend. * – applies to both mentors and mentees.

A characteristic of mentoring activity is the readiness of teachers for it, both mentors and mentees. In our opinion, mentoring activities should not be initiated at all if teachers are unprepared for it, since there is a risk that in this case mentoring will be carried out formally or supported solely on the basis of strict administration.

The interpretation of the concept of “readiness for mentoring activities” is based on two main approaches: subjective and operational-activity. In the first of them (M.I. Dyachenko, L.A. Kandybovich, B.G. Ananyev, V.A. Krutetsky, V.D. Shadrikov, A.A. Derkach, etc.), the teacher’s readiness for mentoring is conceptualized as actualization of his basic values, attitudes, needs and is expressed through a system of professional and personal qualities, subjective perception of the importance of this process and the significance of its results. The second approach (F. Genov, E.P. Ilyin, N.D. Levitov, L.S. Nersesyan, V.N. Pushkin, D.N. Uznadze, A.Ts. Puni, etc.) defines readiness from the standpoint the operational structure of mentoring activities, the teacher’s clear understanding of the algorithm and the relevant competencies for its implementation. In our opinion, it is not the opposition of these approaches that is productive, but their integration into a holistic model of developing a teacher’s readiness for mentoring activities.

By analogy with the research of V.A. Slastenin and L.S. Podymova can talk about the reflexive, cognitive, technological, motivational components of readiness for mentoring [Slastenin, 1997].

The reflective component of readiness is associated with comprehension, awareness of the needs, expectations, goals of mentoring, understanding of one’s own capabilities, accumulated professional experience, and readiness to transfer it. Reflection creates conditions for self-improvement and self-realization of the mentor and mentee.

The cognitive component as a set of subject and psychological-pedagogical knowledge, mastery of methods of translating methodological systems and pedagogical experience creates the basis for the formation of specific content and technologies of mentoring activities.

The technological component is associated with the direct implementation of mentoring, with the ability to develop and implement its various models, analyze problems and one’s own capabilities to resolve them, formulate goals, methods, and means of mentoring activities, predict its results, carry out control and correction.

The most important component in the structure of readiness for mentoring is the motivational component, reflecting a stable need for it; the desire to change one’s position and active participation in the educational process, awareness of the need to enrich professional activities. These needs are the leading motivations for participation in mentoring activities.

Similar readiness structures are represented by O.A. Beketova, I. Dernovsky, T.D. Kuranova, N.S. Ponomareva, T.A. Prishchepa, S.A. Trifonova, G.N. Fomitskaya, T.S. Bazarov, denoting knowledge, emotional and activity components [23. Fomickaja G, 2023].

The objectives of the study were to establish the structure of teachers’ motives that determine their readiness for mentoring activities, assess the significance of factors influencing the motivational and other (cognitive, operational, emotional-volitional) components of readiness for mentoring activities, as well as to identify typical difficulties encountered teachers during its implementation. We proceeded from the assumption that, given the overall greatest importance of the motivational component of readiness, the structure of motives, modality and degree of influence of factors in specific schools may vary, which largely depends on the management of the educational organization.

136 teachers from 4 schools in one of the districts of St. Petersburg took part in the study, 34 teachers from each school with experience in mentoring activities. The age of teachers is 34-56 years old, 39% of them have the highest category, 43% have the first category, 18% have no category, 92% of the respondents were women.

Research results

The study was based on the well-known method of S. Ritchie and P. Martin “Motivational Profile” [Richi, 2004], which makes it possible not only to identify the motives that encourage teachers to mentoring activities or create barriers to it, but also to assess the degree of their expression.

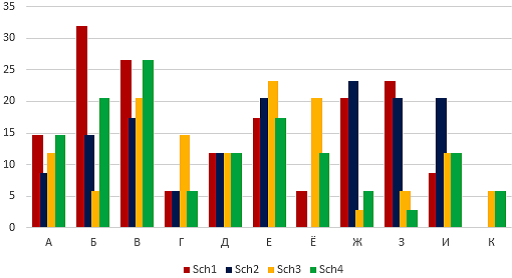

The first question of the survey concerned teachers’ understanding of the importance of mentoring for the development of the school and for them personally. 100% of respondents noted the high relevance and importance of mentoring for modern education. They included the following factors motivating mentoring activities (Table 2, Fig. 1):

Table 2. Factors encouraging mentoring activities

|

Motive code |

Content of the motive |

Number of choices (%)* |

|||

|

School 1 |

School 2 |

School 3 |

School 4 |

||

|

A |

Need to be active |

14,7% |

8,7% |

11,8% |

14,7% |

|

B |

Need for professional recognition, achieving significant results |

31,9% |

14,7% |

5,9% |

20,6% |

|

C |

Need to improve school activities, increase personal contribution to the overall result |

26,5% |

17,4% |

20,6% |

26,5% |

|

D |

Need for a new type of activity, overcoming routine |

5,9% |

5,9% |

14,7% |

5,9% |

|

E |

Need to comprehend and systematize one’s own teaching experience |

11,8% |

11,8% |

11,8% |

11,8% |

|

F |

Need for self-improvement and self-realization |

17,4% |

20,6% |

23,2% |

14,7% |

|

G |

Need for communication and emotional contacts |

5,9% |

0% |

20,6% |

11,8% |

|

H |

Need for additional benefits and privileges |

20,6% |

23,2% |

2,9% |

5,9% |

|

I |

Need for leadership (authority) |

23,2% |

20,6% |

5,9% |

2,9% |

|

J |

Commitment to improving the quality of education |

8,7% |

20,6% |

11,8% |

11,8% |

|

K |

Fear of the consequences of refusing to carry out instructions from management |

0% |

0% |

5,9% |

5,9% |

Legend. * – the number of motives chosen by respondents was not limited. The percentage in the table reflects the share of 34 teachers from each school who chose the corresponding motive.

Fig. 1. Motives that encourage teachers to mentor activities

Testing the hypothesis about the influence of the school on the structure of teachers’ motivation for mentoring activities using the parametric Student’s t-test for independent samples at a significance level of a=0.05 revealed the presence of statistically significant differences in all 4 groups of respondents. At the same time, the most significant influence on the motivation of teachers for mentoring activities is exerted not by external, but by internal factors (school management).

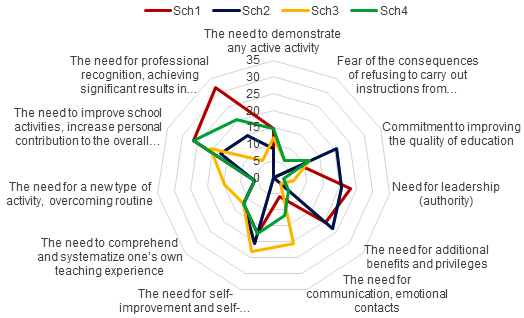

Figure 2 presents the motivational profiles of teachers in the schools studied.

Fig. 2. Motivational profile of the studied schools

In School 1 there are noticeable disproportions in the motivational profile, high ratings of the importance of some factors with low ratings of others. Teachers are focused on administrative (including material) support, professional and public recognition, and consider mentoring as an effective way to improve school activities. In general, the teaching staff is ready to introduce mentoring, provided that it is carried out purposefully, according to a well-thought-out plan, without external pressure and formalism, with sufficient resources and taking into account the capabilities of the school.

Teachers at School 2 have a desire for professional and social recognition with a low level of need to systematize teaching experience and improve the school’s activities. They are characterized by a lack of desire to set ambitious goals and solve complex problems. The leading motive for participation in mentoring activities is the desire to receive decent payment for performing additional duties.

For teachers at School 3 relationships within the teaching staff, a favorable psychological climate, and comfortable working conditions are important. There is a willingness to innovate and to participate in experimental work. The team is aimed at self-improvement, professional growth, the opportunity to express themselves and improve the image of the school. Material incentives for mentoring activities are not of decisive importance.

School 4 shows the greatest variety of motives. What is more important for teachers is not remuneration, but involvement in the affairs of the school, openness of the administration and constant information, support for initiatives and recognition of achievements. They consider mentoring not only a necessary condition for professional growth, but also interesting and socially significant work.

To assess readiness for mentoring activities, the tested tools proposed by S.A. Trifonova seem to be quite relevant [Sebel'dina, 2020].

The following indicators for assessing readiness were named by respondents (Table 3):

Table 3. Indicators of teachers’ readiness for mentoring activity

|

Components |

Indicators |

|

Motivational |

Interest in mentoring |

|

Satisfaction with the process and results of mentoring |

|

|

The need for self-improvement and self-growth |

|

|

Emotional-volitional |

Persistence in achieving the desired result |

|

Accepting responsibility and risk |

|

|

The ability to control your feelings and emotions |

|

|

Creating a welcoming atmosphere and interested participation |

|

|

Operational |

The ability to plan and conduct a pedagogical experiment |

|

The ability to assess the effectiveness of mentoring activities |

|

|

The ability to work in an electronic educational environment, develop innovative educational technologies |

|

|

The ability to create modern educational resources using the methodological potential of mentoring |

|

|

The ability to replicate best pedagogical experience taking into account the conditions of the educational institution |

|

|

Cognitive |

Knowledge of the fundamentals of psychology and pedagogy |

|

Experience in teaching disciplines |

|

|

Proficiency in pedagogical research methods |

|

|

Knowledge of the basics and experience of mentoring |

Next, the degree of importance for respondents of the readiness components was determined (Table 4).

Table 4. Assessing the importance of mentoring components

|

Components |

Number of choices (% ) |

|

Motivational |

52,9 |

|

Emotional-volitional |

22,8 |

|

Operational |

15,4 |

|

Cognitive |

8,9 |

|

Total: |

100 |

The survey showed that respondents, regardless of the degree of their activity in mentoring activities, consider the motivational component to be the most significant (52,9% of choices). The respondents justify the importance of the operational component by the need to expand opportunities and awareness of the choice of pedagogically appropriate technologies for solving professional and pedagogical problems, as well as the importance of developing competencies in planning and conducting pedagogical experiments, replicating advanced pedagogical experience, etc. Only 8,9% of respondents indicated the importance of the cognitive component, which reflects the common misconception among school management that mentoring activities do not require special training.

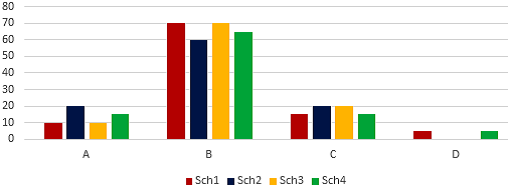

The assessment of teachers’ readiness for mentoring activities was carried out by analogy with the methodology of T.S. Solovyova “Determination of the level of innovation of teachers in the school community”, which makes it possible to differentiate teachers by type of attitude to activity (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Groups of teachers in relation to mentoring activities

“Group A” includes 13,75% of respondents who noted that they are passionate about the idea of mentoring, often act as mentors themselves and on their own initiative, and are ready to actively participate in the development and implementation of innovative mentoring models in their school.

The majority of respondents (66,25%) belong to “Group B”; they recognize the need and importance of mentoring, consider it a natural process for improving school activities and express their readiness to participate in its implementation. Teachers in this group show interest in mentoring, but believe that for its success it is necessary to create conditions and persistence of management, they are ready to participate in it with competent organization, clear setting of tasks and definition of responsibilities.

“Group C” includes 17,5% of respondents who are reserved about mentoring, do not express a desire to become mentors, but are also not ready to decisively refuse such an offer from management. They tend to be cautious in their judgments and assessments, but do not express an openly critical attitude towards mentoring and skepticism about the prospects for its implementation.

“Group D” (2,5%) doubts the feasibility and effectiveness of mentoring. As a rule, such teachers prefer to work “the old-fashioned way” and do not want to leave their “comfort zone.”

None of the teachers surveyed were included in “Group E,” those who categorically do not want to take part in mentoring activities, who have a low assessment of its potential and effectiveness, or who have a negative attitude towards its implementation.

An analysis of the difficulties that impede teachers’ involvement in mentoring activities was carried out using the author’s methodology “Identification of teachers’ difficulties in carrying out mentoring activities” (Table 5).

Table 5. Difficulties preventing teachers from getting involved in mentoring activities

|

Characteristics of activities causing difficulties |

Number of choices (%) |

|

Inability to generalize and systematize one’s own teaching experience |

92 |

|

Lack of mastery of mentoring techniques |

89,3 |

|

Formalism when introducing mentoring, increased reporting, lack of incentives |

89,3 |

|

Poor organization of mentoring, lack of clear definition of functions and powers, low awareness |

89,3 |

|

Preparing mentees to participate in competitions |

83,9 |

|

Difficulty adapting to changes in the content and conditions of activity, fear of new activities |

83,9 |

|

Difficulty in activating the professional activities of mentees, their lack of interest |

81,2 |

|

Heavy workload, lack of time, lack of self-organization skills |

78,5 |

|

Lack of experience in conducting scientific and pedagogical research, organizing research activities of mentees |

75,8 |

|

Professional and personal self-improvement in the process of mentoring activities |

70,4 |

|

Difficulties in communicating with mentees |

59,6 |

|

Inability to interact with the professional community |

54,2 |

|

Poor knowledge of the academic subject and methods of teaching it by mentees |

51,5 |

|

Difficulties in using information technology |

48,8 |

|

Inability to predict potential difficulties for mentees. Adapting mentoring content to the interests and needs of the mentees |

43,4 |

Respondents noted that financial support measures at the initial stage of implementing the targeted mentoring model were minimal due to the lack of formalization of the functionality and responsibility of mentors. This work was organized through the most active and motivated teachers who took on the main load; they were also involved in the direct organization of the process: the development of local documents and report templates, the identification of pairs taking into account the personal characteristics and interests of the participants, the distribution of responsibilities, delegation of authority, etc. Representatives of all schools noted that when implementing the targeted mentoring model, they felt the interest and support of the school administration; after documentation and consolidation of the status, mentors were regularly paid bonuses and incentives. Respondents drew attention to administrative support for initiatives for the participation of mentors and mentees in various competitions, conferences, seminars and other events significant for the school.

Discussion and conclusions

The paradigm shift in modern pedagogy dictates the need to rethink and scientifically substantiate the phenomenon of mentoring in its modern interpretation. The success of education modernization will largely be determined by the competence and authority of teacher-mentors, the level of their methodological skills, their readiness to comprehend and transmit the best pedagogical practices, which requires the creation of a targeted and comprehensive system for training mentors. The condition for the success of mentoring is the motivation and positive attitude of mentors and mentees towards it, understanding the role of mentoring in the professional formation and development of a modern teacher.

By analyzing the practice of organizing mentoring in the schools under study, it is possible to differentiate the role models of participants in mentoring activities depending on their chosen behavioral strategies.

- Proactive development of content, forms and methods of mentoring activities and their active implementation, readiness for a significant investment of time and effort. According to our research, this strategy is implemented by 1-2% of mentor teachers.

- Amateur activity in mentoring activities is a behavioral strategy that presupposes explicit support by the teacher for the institution of mentoring and interested participation in its implementation. This model of behavior is followed by about 10% of teacher-mentors.

- Demonstrative activity under pressure from management, teaching staff and/or circumstances. This strategy consists of formally performing the functions of a mentor with a moderate degree of activity, which may completely disappear when difficulties arise. This strategy is followed by the largest – 60-65% – group of teacher-mentors.

- Passive mentoring. Characterizes the strategy of avoiding direct participation in mentoring activities, discussing its content and organizational forms, and unwillingness to accept the responsibility associated with mentoring. The share of such teachers is estimated at approximately 20%.

- Active resistance to the introduction of mentoring, manifested in various forms: its criticism as unnecessary, ineffective and even harmful; accusing active mentors of selfish motives; in appealing to previous successful experience in the absence of mentoring; in actions that complicate the process of introducing mentoring or are directly directed against it. This position, according to the study, is occupied by 4-5% of teachers.

The data obtained on the readiness of teachers for mentoring activities and the leading motives for participation in it indicate insufficiently conscious work of school leaders to create positive motivation for mentoring, poor knowledge of the motives that encourage teachers to be active, and ways of updating them. It is significant that 100% of the teachers who took part in the study note the importance of mentoring for modern education and recognize the need for its competent organization, and generally have a positive attitude towards mentoring, provided that it is purposefully and thoughtfully implemented with sufficient resources and taking into account the capabilities of the school. More than 50% of respondents consider motivational readiness for mentoring activities to be the main factor in its success. The motivations of teachers to participate in mentoring activities have significant differences and are determined by various factors that reflect the specifics of schools. This means that given the general conceptual framework, there is not and cannot be a universal model and universal technology for introducing mentoring; the system will be viable and effective only if it is designed and implemented taking into account the conditions and characteristics of a particular school and with the active participation of teachers working there. In this regard, it’s recommended to continue research of the correlation between teachers’ readiness for mentoring activities and intra-organizational factors (management models and management style), the degree of support for this activity by management, the level of organizational culture, resource and methodological support, etc., as well as the impact of teachers’ readiness for mentoring activities on its performance, level of success and achievements of the school.