Introduction

Sensory deprivation, such as deafness, can alter the processing of information from other sensory modalities (Pisoni et al., 2007; Conway et al., 2011; Sur, 2004). Neural plasticity—the brain’s capacity to adapt and reorganize its structure—facilitates adaptive changes following sensory deprivation (Thakur et al., 2023; Conway et al., 2011). The loss of one sensory modality may thus trigger reorganization in intact sensory systems. Evidence suggests that early auditory deprivation (Marschark et al., 2019) induces widespread changes in neurocognitive functions (Lima et al., 2023; Lauriello et al., 2024), particularly in visual information processing (Dawson et al., 2002), which is critical for calibrating visual functions (Bavelier et al., 2010).

Notably, prior studies have predominantly focused on visual attention, often neglecting a comprehensive examination of visual gnosis and broader visual information processing strategies. Nevertheless, some research confirms that children with hearing impairments exhibit deficits in processing both auditory and visual information concurrently. Children with cochlear implants attend to visual information but may process it differently from their peers, potentially resulting in slower overall responses (Bottari et al., 2014). This manifests in atypical strategies for processing visual and visuospatial information (Conway et al., 2011), as well as difficulties in tasks involving visual sequence discrimination, visual memory, and visuomotor sequencing (Bottari et al., 2014).

Historically, it has been assumed that deaf individuals possess superior visuospatial abilities compared to their hearing peers, prompting the widespread use of visual aids in their education (Marschark et al., 2019; Pisoni et al., 2007; Kornienko, 2021). However, studies on learning difficulties indicate that these challenges are frequently linked to visual functions. For example, 20% of preschool children experience difficulties with visual analysis and recognition, impacting their academic performance (Akhutina et al., 2001; Korsakova et al., 2022). Furthermore, children with hearing impairments exhibit distinct patterns of visual attention during learning tasks (Monroy et al., 2021) and perform less effectively in tasks requiring the monitoring and sequencing of visual stimuli (Dawson et al., 2002; Kyle et al., 2011; Thakur et al., 2023). Failure to account for these specificities in visual processing can lead to reduced academic success (Kyle et al., 2011) and the adoption of ineffective teaching methods. This is evidenced by a 4% disparity in learning efficacy between hearing and hearing-impaired groups, particularly in reading skills, comprehension, and vocabulary acquisition (Thakur et al., 2023; Yurkovic-Harding et al., 2022).

Moreover, while deaf children may possess typical visual attention mechanisms, they often struggle with encoding and processing stimuli into phonological representations (Almomani et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2010; Daza et al., 2013; Pisoni et al., 2007). Their performance in visual tasks largely depends on whether stimuli can be verbally encoded or named (Daza et al., 2013; Pisoni et al., 2007) and on their preferred language skills, irrespective of modality (Marschark et al., 2019). Consequently, it is imperative to investigate not only the role of visual aids but also their mode of presentation.

Drawing on prior research, this study addresses two key issues. First, it employs eye-tracking to explore the cross-modal effects of sensory deprivation on both spatial and temporal aspects of visual attention and the overall processing of visual information in children with hearing impairments. Unlike previous studies, this research aims to extend knowledge beyond the reorganization of visual attention to encompass visual gnosis and comprehensive visual information processing strategies. Second, it examines the influence of different presentation formats of visual aids—such as auditory-visual formats or visual lexical supports—on the learning process in children with hearing impairments.

Thus, the primary objective of this study is to use eye-tracking to identify the distinctive characteristics of visual information processing in children with hearing impairments resulting from early auditory deprivation. By utilizing visual educational materials, the study seeks to determine how these processing specificities manifest in learning situations, particularly in relation to the format of visual aid presentation and the use of visual, auditory-visual, and lexical supports.

Materials and methods

Study Sample. The study involved preschool children aged 5.5-7 years. The sample included 15 children with hearing impairments (sensorineural hearing loss, class H90 per ICD; average hearing threshold at frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz >90 dB), comprising 8 boys and 7 girls, with a mean age of 6 years. Cochlear implants were fitted at age 3. The sample was matched for the timing of hearing defect onset and cochlear implantation. Post-implantation rehabilitation occurred in a specialized kindergarten where the study was conducted. All participants demonstrated sufficient cognitive development, speech recognition thresholds, and comprehension of spoken language to participate. They also had adequate experience with sound-amplifying devices. The control group consisted of 20 typically developing preschoolers (8 girls, 12 boys; mean age 6.1 ± 0.4 years).

Procedure. Given that post-cochlear implantation efforts focus on speech development and vocabulary expansion, visual educational materials were selected to activate the children’s vocabulary. Illustrations from the ABC book for hearing-impaired children by N.Yu. Donskaya and N.I. Linikova were used as stimuli. These materials establish connections between auditory and visual representations of objects and their verbal labels, serving as visual aids to enhance vocabulary and phonemic hearing. The materials included:

- Subject and plot illustrations for learning object names and expanding vocabulary.

- Visual word representations: some illustrations featured lexical items (object vocabulary) in frames beside the objects, functioning as visual word supports (see Figure 1). Hearing-impaired preschoolers, as part of pre-literacy training, use visual aids such as word cards for speech development and are proficient in reading them.

Illustrations with and without captions were employed to assess how visual lexical supports influence visual attention in children with hearing impairments. Both subject illustrations (single objects) and plot illustrations (scenes) were included, differing in complexity, with plot illustrations being more abstract and thus more challenging to interpret.

The method of instruction delivery by the adult experimenter was varied:

- Verbal instruction only (triggering auditory-visual perception): The adult provided a verbal instruction specifying which object the child should identify and point to (e.g., “Show me where the doll is in the picture”).

- Instruction with visual lexical support (triggering visual perception): The adult provided the instruction by pointing to the lexical label of the object (e.g., saying “Show me where…” and indicating the word “Ball” in the frame).

The control group of typically developing children underwent the same procedure under identical conditions.

Equipment. Data were recorded using a stationary GP3 eye tracker, with a tracking accuracy of 0.5–1°, a sampling rate of 60 Hz, and 5- or 9-point calibration. The head movement range was 25 cm horizontally and 11 cm vertically, with a desktop mount setup. Calibration was accepted if the average error was less than 0.30° of visual angle. Data were processed using the “Neurobureau” software (Neuroiconica assistive).

Stimuli were presented on a 15.6-inch laptop screen (1920 x 1080 resolution, 16:9 aspect ratio). The viewing distance was 60 cm, and images were 600x480 pixels. Image transitions were controlled by the experimenter via key presses following the child’s response.

For comparing oculomotor activity between the two experimental series in children with hearing impairments, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used. To compare oculomotor activity between children with hearing impairments and typically developing children, the t-test was applied. Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS V.23.0.

Results

Initially, we compared the oculomotor activity of children with hearing impairments and typically developing children when identifying objects in educational illustrations (both with and without visual lexical supports). The t-test was employed for this analysis (Table 1).

Table 1

Descriptive statistics of oculomotor activity in children with hearing impairment and typically developing children

|

|

M (SD) |

t-test |

||||||

|

t-value |

df |

p-value |

||||||

|

number of fixations before the first fixation |

typically developing children |

0 |

-4,58 |

23 |

0,003 |

|

||

|

children with hearing impairments |

0,75 (0,16) |

|

||||||

|

time to first fixation |

typically developing children |

0 |

-4,52 |

23 |

0,003 |

|

||

|

children with hearing impairments |

0,24 (0,05) |

|

||||||

|

total viewing time |

typically developing children |

10,47 (0,73) |

-5,37 |

23 |

0,0001 |

|

||

|

children with hearing impairments |

26,62 (2,91) |

|

||||||

|

number of returns to the area of interest |

typically developing children |

2,81 (0,4) |

-4,83 |

23 |

0,0001 |

|

||

|

children with hearing impairments |

14,85 (2,46) |

|

||||||

|

average duration of fixations |

typically developing children |

0,41 (0,03) |

-2,18 |

23 |

0,051 |

|

||

|

children with hearing impairments |

0,71 (0,13) |

|

||||||

|

total number of fixations |

typically developing children |

28,36 (3,95) |

-2,37 |

23 |

0,030 |

|

||

|

children with hearing impairments |

54 (10.04) |

|

||||||

Children with hearing impairments exhibited a higher number of fixations before the first fixation on the target area, longer time to first fixation, and increased average fixation duration. These findings indicate prolonged temporal characteristics of visual information processing compared to typically developing children. Additionally, these children made more fixations and spent more time viewing the illustration before identifying the target object, suggesting that objects were less noticeable or harder to detect. The extended viewing time and higher average fixation duration point to an increased cognitive load during perception, further supported by the greater number of returns to the area of interest and the elevated total number of fixations during the viewing period.

Next, we analyzed how oculomotor activity in children with hearing impairments varied when identifying subject and plot illustrations under different presentation conditions: auditory-visual presentation (verbal instruction with visual aid) and presentation with visual lexical support (instruction with a visual word label). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for this comparison (Table 2).

Table 2

Descriptive statistics of oculomotor activity in children with hearing impairments under different presentation conditions

|

M (SD) |

||||||

|

Subject illustrations |

number of returns to the area of interest |

total number of fixations |

number of saccades |

total scan path length |

total ssan path langth |

|

|

M (SD) |

||||||

|

Visual aid without lexical designation |

14,85 (2,46) |

54 (10,04) |

38,14 (8,43) |

150,30 (26,06) |

0,82 (0,000001) |

|

|

Visual aid with lexical designation |

8,28 (1,72) |

29,71 (9,19) |

20,42 (7,61) |

71,43 (21,38) |

0,75 (0,000001) |

|

|

Criterion statistics |

||||||

|

Z |

-2,17 |

-2,35 |

-2,11 |

-2,35 |

-3,74 |

|

|

p-value |

0,03 |

0,01 |

0,03 |

0,018 |

0,000 |

|

|

M (SD) |

||||||

|

Subject Illustrations* |

number of returns to the area of interest |

total number of fixations |

total number of saccades |

total scan path length |

total ssan path langth |

|

|

A series of experiments without lexical designation |

8,8 (0,57) |

41,8 (11,77) |

32 (9,235) |

167,84 (50,64) |

0,88 (0,0001) |

|

|

A series of experiments with lexical designation |

3 (1,05) |

24,4 (8,04) |

20,4 (7,013) |

91,84 (27,625) |

0,86 (0,0001) |

|

|

Criterion statistics |

||||||

|

Z |

-2,53 |

-2,81 |

-2,53 |

-2,11 |

-3,162 |

|

|

p-value |

0,011 |

0,005 |

0,011 |

0,035 |

0,002 |

|

When visual aids were presented with visual lexical supports, children with hearing impairments exhibited fewer returns to the area of interest, fewer fixations, and fewer saccades, indicating easier perception and reduced cognitive load compared to identification via auditory instruction alone. The total scan path length was also shorter with visual lexical supports, suggesting less need for detailed scanning and reinforcing the reduction in cognitive load. Additionally, the ratio of the area of interest to the total stimulus area decreased with visual lexical supports, reflecting a more focused search area and clearer identification of the target region. These patterns were consistent across both subject and plot illustrations.

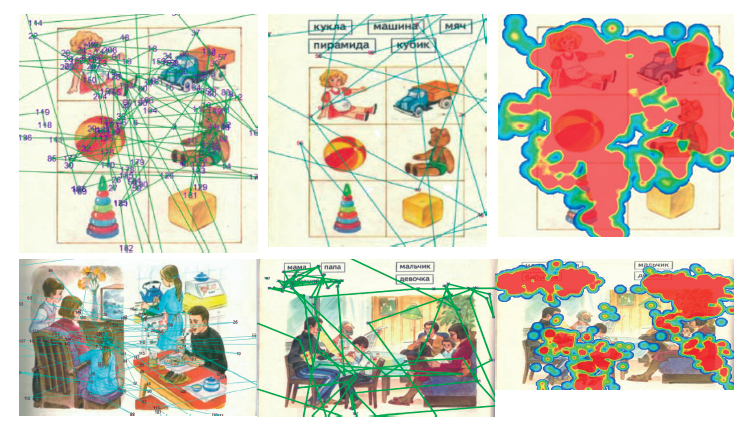

Further analysis of eye movement graphs and heat maps (Figure 1) confirmed that visual lexical supports reorganized visual attention and information selection in children with hearing impairments.

When visual aids were paired with lexical supports, children with hearing impairments displayed fewer fixations and transitions, shorter scan paths, and more targeted fixations. Fixations were more sequential, with reduced need to revisit previously viewed areas, and the areas of interest were more clearly defined (narrowing the operational search field and reducing chaotic scanning). The spatial density of fixations was more concentrated, with attention focused on central areas of interest. In contrast, auditory-visual presentation resulted in broader attention distribution, with peripheral areas processed more extensively.

Compared to typically developing children, children with hearing impairments exhibited differences in the spatial distribution of attention, including the direction and sequence of visited areas, repeatability, and number of shifts. Their operational field dynamics (areas of interest and search zones) were broader, often encompassing peripheral and non-target areas. Typically developing children showed more sequential fixations in target zones, with clearer areas of interest and less need for detailed scanning.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to investigate the unique characteristics of visual information processing and the reorganization of visual attention in children with hearing impairments when perceiving educational visual aids. Analysis of eye movement patterns revealed several key insights.

First, our eye-tracking data complement previous findings that auditory deprivation in children with cochlear implants alters the sequence of visual information processing (e.g., Marschark et al., 2019), the spatial distribution of visual attention (e.g., Bavelier et al., 2010), and results in a broader attentional range (e.g., Chen et al., 2009; Tharpe et al., 2005). We also observed distinct visual search strategies and frequent attentional shifts and distractions in children with hearing impairments.

Consistent with earlier research, our results suggest that children with hearing impairments may employ parallel rather than sequential processing of visual information (Stivalet et al., 1998), leading to an expanded search area and a shift of interest boundaries to the periphery. Additionally, their processing strategy appears more “bottom-up,” characterized by chaotic, non-sequential selection of informational features, frequent strategy changes (particularly under difficulty), and less efficient perceptual actions.

The study also supports the view that temporal (sequential) processing of visual information is altered in children with hearing impairments, potentially affecting visual-temporal processing thresholds (e.g., Nava et al., 2008; Iversen et al., 2015; Heming et al., 2005). This may influence the time required to detect stimuli, identify and compare multiple stimuli, and the order of stimulus inspection. Increased temporal characteristics (e.g., detection time, viewing time) may be attributed to delays in auditory signal input from the cochlear implant, disrupting the synchronization of auditory and visual stimuli. This effect may be compounded by the cognitive complexity of perception due to limited vocabulary and challenges in linking word sounds to visual objects.

Furthermore, our findings indicate that children with hearing impairments exhibit variations in the depth and intensity of visual information processing, as well as in the noticeability (“recognizability”) of images and the mental load associated with perceiving educational visual aids.

Conclusions

Through eye-tracking, this study has expanded our understanding of the cross-modal effects of sensory deprivation on both spatial and temporal processes in visual information processing among children with hearing impairments.

Additionally, it provides new insights into the impact of different presentation formats of educational visual aids—specifically auditory-visual formats versus visual lexical supports—on the learning process in these children.

Our results confirm that the effectiveness of visual perception in children with hearing impairments depends on the modality of presentation, including whether stimuli can be verbally encoded (Dawson et al., 2002; Pisoni, 2007) or supported by visual lexical cues. The presentation format significantly influences how visual attention is structured in these children. Specifically, using visual aids with auditory instructions alone is less effective than combining visual aids with visual lexical supports. The latter reduces cognitive load, requires less detailed scanning, and facilitates faster, more efficient selection of visual information. Auditory-visual presentation is less effective, likely due to delays in auditory input from the cochlear implant, which may hinder the processing of sequential auditory-visual stimuli. This is further complicated by difficulties in linking auditory word representations to visual objects, exacerbated by limited vocabulary. Thus, a bimodal approach incorporating visual supports is essential.

These findings have practical implications for the education and rehabilitation of children with hearing impairments post-cochlear implantation. Effective processing of sequentially presented visual stimuli, such as educational visual aids, is vital for speech development, vocabulary acquisition, and reading skills. In the learning and rehabilitation process, transitioning from auditory-visual to purely auditory perception of spoken language is a key goal for children with cochlear implants. Our data illustrate how visual aids can be integrated into this process to support this transition.

Limitations. The primary limitations stem from the small and unique sample of preschool children with cochlear implants, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Future research should aim to expand this sample. Additionally, further studies should compare different age groups of children with hearing impairments to explore age-related differences in visual information processing and the role of cochlear implant duration in compensating for early auditory deprivation. Examining visual information processing across varied experimental learning contexts is also warranted.