Introduction

Recent studies highlight several issues in teachers' play support: the substitution of play with quasi-play (Galasjuk et al., 2023; Iakshina, Le-van, 2022); a lack of understanding of the genesis and key features of play, the absence of appropriate pedagogical goals, and the low quality of the play environment (Shiyan et al., 2021); teachers' didactic approach instead of playing as a partner with the child (Abdulaeva, Alieva, 2020; Iakshina, Le-van, 2022; Bredikyte, 2022; Devi, Fleer, Li, 2021).

Teachers interpret play differently, reflecting two historically established perspectives: utilitarianism and the recognition of play's intrinsic value (Galasjuk et al., 2023; Iakshina, Le-van, 2022). The utilitarian approach involves organizing designated play areas, where play is viewed as a structured activity aimed at developing children's understanding of specific social or professional domains and behavioral norms. From this perspective, teachers observe many aspects of play (e.g., speech development, practical skills, communication, and conflict resolution) but overlook the play itself—its dynamics and development—and thus fail to set pedagogical objectives aligned with the logic of play development. The second perspective focuses on natural forms of play, broadly defined by motivation ("the motive of play lies not in the result of the action but in the process itself" (Leontiev, 1981, p. 486)) and the child's freedom: play is seen as an activity independent of adult involvement (Smirnova, 2014).

Both perspectives entail risks and may underlie ineffective teacher’s play support. In the first case, play is replaced by quasi-play—play in form but not in content. In the second, key criteria of play are neglected (e.g., the divergence between visible and semantic fields (Vygotsky, 2004), dual subjectivity (Kravtsov, Kravtsova, 2017)), and the emergence of cultural, higher forms of play—such as narrative play—is unsupported, hindering the development of play as an activity (Galasjuk et al., 2023).

Effective play support involves creating conditions for play development, including teacher’s participation as a partner and mediator in joint play, as well as indirect support (observing play, assisting in organizing play spaces, providing materials, commenting, and aiding children from a non-play position) (Galasjuk et al., 2023; Singer, DeHaan, 2019; Iakshina, Le-van, 2022; Bredikyte, 2022; Loizou, Loizou, 2022). Amplifying play conditions in kindergartens requires studying teachers' play support practices and factors enhancing its effectiveness.

Teacher’s play support is not limited to spontaneous play with children (where the teacher occasionally joins in). It is a guided process requiring pedagogical objectives aligned with play dynamics, children's needs, and their zone of proximal development. Effective play support simultaneously boosts play development, remains responsive to children's needs (Bredikyte, 2022; Devi, Fleer, Li, 2021), and involves the teacher's analysis of both the play process and its broader development (Singer, DeHaan, 2019). Additionally, for appropriate engagement in children's play, teachers must analyze their own actions, their impact on children, recognize emerging challenges, and adjust flexibly based on children's feedback (Pramling et al., 2019).

In this study, pedagogical reflection is understood as stepping beyond immediate activity to analyze it, identify difficulties, and interpret them (Belolutskaya, Kristofik, Mkrtchyan, 2022; Shiyan et al., 2019). It is viewed as a mechanism for aligning developmental values and pedagogical practices (Isaev, Kosaretsky, Slobodchikov, 2000). We hypothesize that pedagogical reflection is a factor enhancing the effectiveness of play support. While the value of reflection in educational processes is acknowledged, its low levels among teachers struggling to analyze their own practice and the process of reflection as professional challenge are noted in several studies (Groschner et al., 2018; Pehmer, Groschner, Seidel, 2015). However, no research has examined the role of pedagogical reflection in preschool teacher' play support.

Research Objective: To establish the interrelation between the quality of play support and teachers' level of reflection.

Hypothesis: The quality of play support is linked to the level of pedagogical reflection.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in 2022–2023. The quality of play support was assessed based on video recordings of teachers and children playing together in their usual kindergarten setting.

Video analysis included three levels of data interpretation (Hedegaard, 2008): review and analysis of all videos (presence of spontaneous play, teacher’s involvement, its duration); identification of categories for analyzing teacher’s actions; thematic analysis based on the cultural-historical approach to understanding adults' role in play development.

Play support quality was evaluated using the following parameters, derived from the cultural-historical perspective on play (Galasjuk et al., 2023; Shiyan et al., 2024):

- Use of unstructured materials (UM).

- Teacher’s positioning in joint play (see Table 2).

- Predominant type of teacher’s suggestions during play.

- Predominant type of teacher’s response to children’s suggestions (Singer, DeHaan, 2019).

- The effect of teacher’s actions—whether they act within the children’s zone of proximal development (i.e., whether play advances to a more complex level, remains unchanged, or deteriorates after teacher’s involvement).

Each parameter was scored from 0 to 2–3 points (minimum total score: 0, maximum: 11). Three levels were established based on the cultural-historical understanding of teachers' role in play development (Galasjuk et al., 2023; Kravtsov, Kravtsova, 2017; Shiyan et al., 2024; Elkonin, 1999) (Table 1).

Table 1

Play support quality levels

|

Low (0-4 scores) |

UM are unavailable, teacher’s positioning in play: outsider, didactic, formal functionary. A teacher's actions destroy the children's play. A teacher does not make suggestions and ignores the suggestions of the children playing. |

|

Medium (5-8 scores) |

Only limited UM are available, teacher’s positioning in play: commentator, stage manager, observer, partial involvement in play, leader. A teacher suggests ideas about play-plot development. There are no changes in children’s play. |

|

High (9-11 scores) |

Ample UM are available, teacher’s positioning in play: mediator, partner. The teacher notices and supports children’s play ideas. As a result of teachers’ actions, children’s play develops, becomes more complicated, and new ways of playing appear. |

Legend: UM – unstructured materials.

The level of pedagogical reflection was assessed based on teachers' written comments on their own video recordings. The comments were free-form responses to questions that guided teachers in analyzing their own actions and identifying challenges. Prior to this, teachers received a list of questions for video analysis and could discuss them with experts to clarify wording and ask follow-up questions.

Each teacher was asked to watch their own video of play support and evaluate it by answering the following questions:

- What gaps in the children's play development did I notice in the video?

- What strengths in the children's play development did I observe in the video?

- What pedagogical objective did I have when joining the children's play?

- What was effective in my involvement in the children's play? How did I recognize this?

- How did my involvement affect the children's play?

- What was ineffective in my involvement in the children's play? How did I recognize this? Why might this have happened?

- What could I do differently next time regarding the children, considering this experience?

- What could I do differently next time regarding myself and my actions, considering this experience?

During the analysis, experts evaluated educators' video comments based on five parameters:

- Alignment of pedagogical objectives with children's play in the video: How well the teacher identifies gaps in play and sets pedagogical objectives accordingly.

- Understanding of play development dynamics (in relation to the video): Whether the teacher recognizes how their actions influence changes in children's play.

- Consistency between pedagogical objectives, actual actions, and self-assessment of impact: The teacher's ability to assess whether observed play aligns with their intended objectives and actions.

- Awareness of personal strengths and weaknesses, planning next steps for play facilitation (regarding children and own actions): The teacher's capacity to analyze their own actions in joint play and incorporate this into future planning.

Each parameter was scored on a scale from 0 to 3 (minimum total score: 0, maximum: 15).

Four experts participated in assessing the videos and comments: a practitioner recognized for high-quality play facilitation (based on the PERS assessment), two researchers from different universities with over 30 years of experience in play research and around 100 publications on the topic, including peer-reviewed journals, a certified expert in educational quality assessment. All experts work within the framework of cultural-historical psychology and activity theory. Inter-rater reliability was 85%. To assess reliability, experts independently evaluated two play support videos and two corresponding comments (randomly selected) using the defined parameters. The percentage of exact matches between expert scores and the agreed-upon assessment was then calculated.

Sample Characteristics

The study initially included 39 preschool teachers from various regions of the Russian Federation. After preliminary analysis, 11 videos were excluded as they depicted quasi-play—scripted scenarios predetermined by the educator. The remaining 28 teachers from 19 educational institutions formed the final sample. The majority of teachers (47, 6%) have more then 11 years of teaching experience, 28,6% – 3–10 years, 25% – less than 3 years. 71,5% of teachers have higher education, 21,4% – vocational education, 7,1% – incomplete higher education. The sample was formed on a voluntary basis.

Results

Correlation analysis revealed a significant positive relationship between the quality of play support and the level of reflection (Spearman's r = 0,71, p < 0,01). Teachers who created conditions to support play were more likely to accurately identify their own and the children's strengths and weaknesses in play, set appropriate pedagogical objectives, and plan effective next steps. Conversely, teachers who ignored play, engaged in it superficially, or used play solely for teaching tended to provide vague, generalized comments, failed to articulate pedagogical objectives, and struggled to identify their own or the children's play-related challenges.

Next, we examine in more detail the levels of play support and reflection among the preschool teachers in the study sample.

Quality of play support: The average score for play facilitation was 5,8 (SD = 2,5, median = 6, min = 1, max = 10). The sample was predominantly characterized by medium (53,5%) and low (35,7%) levels of play support, with only 10,7% of teachers demonstrating high-quality play-support (Table 1). Below, we analyze the five parameters used to assess play support quality.

Use of unstructured materials (UMs): Most teachers provide children with access to unstructured materials during play: 39,3% of videos are dominated by UMs, 35,7% use only few UMs, and 14,3% have some variety of UMs. Only 10,7% of videos do not have UM available for children to play.

Teacher’s predominant positioning in play support: The teacher's role was a key factor in determining the quality of play facilitation (Table 1). Based on engagement levels, the observed positions (Table 2) fell into three categories: ignoring play (outsider position) – the educator remains uninvolved; indirect support – the teacher does not join the play but creates conditions for play (e.g., organizing space, providing materials); active participation in play – the teacher engages as a play partner (Singer & DeHaan, 2019).

High-quality play support involved not only indirect support but also active participation as a play partner. In contrast, low-quality play support often disrupted play by imposing didactic tasks or engaging superficially, pulling children back into a real field, non-playful mode.

Table 2

Teacher’s positioning in play support

|

Position |

Teacher’s actions on the video |

|

Didactic |

Imposes external goals, directs and organizes children, gives instructions |

|

Outsider |

Doesn’t participate in play, ignored playing children, a teacher is busy with other tasks |

|

Intrusive interviewer |

Intrusively asks children questions that interrupt their play |

|

Formal functionary |

Acts in formal and stereotypic way, only imitates play |

|

Observer |

A teacher is near playing children, involved in play observation |

|

Commentator |

Attentively observes and comments on children’s play without participation in it |

|

Stage manager |

Helps with play materials and space transformation, suggests ideas without participation in play |

|

Partial involvement in play |

Occasionally participates in joint play, accepts children's invitation to join their play, but in play the teacher only follows children without suggesting their own ideas |

|

Play leader |

A teacher is emotionally involved in the process of play, actively suggests ideas, seizes the initiative and leads the play process |

|

Partner |

A teacher is emotionally involved in the process of play, accepts children’s ideas, makes their own suggestions in response to children’s ideas, accepts refusal if it occurs, maintains the balance of teacher-child initiatives |

Teachers’ positioning in joint play as partial involvement, play leader, and partner involve the teacher’s participation in play with children but differ in the balance of initiative between the adult and the children. Partial involvement in play: the teacher merely follows the children’s lead, offering no play ideas of their own throughout the recorded play session. Play leader: the teacher takes most of the initiative, actively proposing ideas, while the children follow their lead. Partner: a balanced exchange of initiative is maintained between the teacher and children throughout the play session.

The most common positions observed were formal functionary, didactic, partial involvement in play, observer, and questioner, while the play leader and partner positions were the least frequent. Most teachers adopted two or more positions (often combining those related to indirect play support). For a third of the teachers, positions negatively impacting children’s play prevailed—outsider, didactic, intrusive questioner, and formal functionary (Devi, Fleer, & Li, 2021). The predominance of a particular role was considered in assessing the levels of play facilitation (see Table 1). For 14,3% of teachers, the dominant roles were partner and play manager.

Predominant types of teacher suggestions during play: teachers most often suggested ways to expand the play’s storyline. Only a third introduced problematization—a play idea introducing a conflict or challenge that required resolution while maintaining and advancing the play (Kravtsov & Kravtsova, 2017; Pramling et al., 2019).

Teacher’s typical response to children’s suggestions: the most common pattern was two-sided interaction (60,7%), where teachers primarily accepted children’s suggestions without imposing their own. In 25% of cases, teachers occasionally rejected children’s ideas, while 14,3% ignored them entirely, insisting on their own proposals.

Impact of teacher’s actions: in a third of cases, teachers’ actions had no effect on children’s play. Most often, their involvement led only to minor plot changes, repetition of play actions, or an increased use of substitution. Complexity and new play strategies emerged in just 7,4% of cases following teacher intervention.

Level of development of pedagogical reflection: the average score for pedagogical reflection across the sample was 4 (SD = 3,6, Mdn = 3,5, min = 0, max = 11).

Teacher comments were categorized into three types based on: the core pedagogical goal, understanding of the teacher’s role, ability to identify challenges and difficulties, relevance to the video recorded play session (see Table 3).

Table 3

Teachers’ comments on their own videos

|

Type of the comment |

Pedagogical goal |

Teacher’s role |

Challenges and difficulties |

Semantic connection between comment and video |

|

Abstract words about play (39,3%) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Play as a form of teaching (21,4%) |

Didactic |

Transfer of knowledge, expansion of ideas, exploitation of play for learning |

- |

- |

|

Play as valuable for itself (39,3%) |

Play support and development |

Play development through providing appropriate conditions, observation and participation in play |

Highlights the deficiencies of their own play |

Based on play observation |

Only teachers who viewed play as intrinsically valuable were able to accurately identify challenges in their own practice.

Understanding the dynamics of children’s play development (in relation to video observations). Teachers rarely identified specific play development deficits in children’s play: plot-related issues (15%), role-playing difficulties (5%), brief role-based dialogues (2%), challenges with object substitution (6%), repetitive play actions (6%), lack of initiative and self-regulation (5%), limited imagination (2%), dominance of object play (2%), difficulty maintaining play rules (1%). The most noticeable deficits for educators were those not directly tied to play development specifics: communication and social interaction problems (23%), speech-related issues (11%), lack of real-world knowledge/experience (9%).

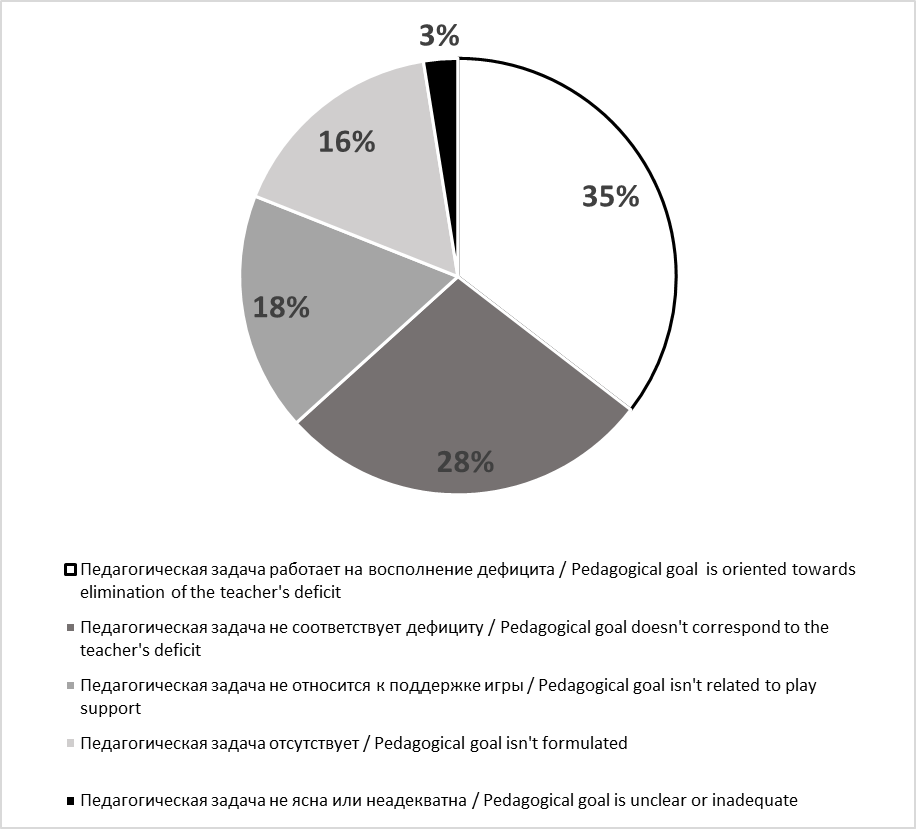

Alignment between pedagogical goals and children’s play (as seen in video recordings). Based on the consistency between the play deficits noted by teachers and their proposed pedagogical interventions, five response types were identified (see Figure).

Understanding the deficits and strengths, planning the next step in play support in relation to children and teachers’ actions. Most teachers (57,2%) were unable to analyze their own strengths and weaknesses in supporting children’s play. 21,4% correctly identified their deficits (based on video analysis) but did not consider them in planning. Only 21,4% used their identified gaps as a basis for planning next steps in play support.

Alignment between pedagogical goals, actions, and evaluation of the effect of teacher’s actions. About one-third of teachers successfully identified deficits in children’s play development and formulated appropriate pedagogical goals. The remaining teachers showed a disconnect between observation, understanding of play development, and goal formulation—their stated goals did not match the actual children’s needs observed in play.

Discussion

The study revealed that teachers rarely play as the partner and mediator, that is necessary for fostering play development (Abdulaeva, Alieva, 2020; Kravtsov, Kravtsova, 2017; Singer, DeHaan, 2019). This reflects a trend observed across different countries (Bredikyte, 2022; Devi, Fleer, Li, 2021). The prevalence of didactic and formal functionary approaches is concerning: exploiting play for instructional purposes pushes children into action within the real-field and disrupts the meaning-field of play (Galasjuk et al., 2023).

Unlike findings from other studies, in our case, teachers seldom took an outsider position, which may be explained by the sample's specific characteristics (self-selection principle) as well as the initial requirement for video submissions (a continuous episode of joint play between children and a teacher). Some teachers assumed roles that supported play development—either as co-players with partial involvement in play or play leaders—meaning they engaged in joint play without imposing external goals, yet without fully transitioning to a partner role that requires a balance of initiatives between adults and children.

The study identified a lack of reflection and difficulties in teachers' understanding of play development specifics: a third of the initial sample submitted videos of quasi-play instead of genuine play, and more than half of the teachers failed to highlight key aspects of play development or articulate pedagogical objectives related to play in their comments.

The analysis of videos and teachers’ comments aligns with other research, pointing to two opposing trends in preschool practice: while generally acknowledging the value of children's play, teachers either support it without engaging in it or adopt a utilitarian attitude, attempting to control and totally guide it (Iakshina, Le-van, 2022). This underscores the need to find tools that help teachers shift from didactic position to a mediator role in joint play with children. A telling illustration is one teacher's comment, which reflects the principles of directive pedagogy: "It's very difficult to organize truly spontaneous play because children's experiences vary, and it's hard to engage everyone."

The findings highlight a gap between teacher training (most teachers hold higher pedagogical degrees) and actual practice, as well as shortcomings in teacher education programs (Samoderzhenkov et al., 2021; Iakshina, Le-van, 2022) and workplace methodological support for educators.

The interrelation between the level of reflection and the quality of play support supports our research hypothesis and suggests that reflective analysis of play and recognizing one's own play-related deficits do not hinder joint play. This connection may indicate that the level of reflection enhances the quality of the activity it is directed at: if a teacher can analyze their own play with children and identify both their own and the children's play deficits, they will engage in joint play more appropriately and support it more effectively.

An alternative interpretation of this correlation, requiring further verification, is also possible: extensive practical experience among play-oriented teachers may provide an intuitive understanding of joint play dynamics, which, in turn, influences the level of reflection, enabling educators to observe more sensitively, discern nuances, and analyze ongoing processes. However, intuition is always a condensed, instantly unfolding, yet not always reflected-upon experience—it may remain unconscious due to a lack of appropriate tools and terminology. Reflective analysis of one's own play equips teachers with a tool that helps transition play support from an intuitive to a conscious and deliberate level, moving from lower to higher forms of behavior.

Conclusion

The design of our study does not allow us to conclusively determine whether a high level of pedagogical reflection influences the transition to a partnership role in joint play. However, we can hypothesize that understanding the specifics of play activities and reflecting on one’s own challenges may be among the factors that enhance the quality of play support. The process of reflective analysis is a cognitively guided one that can enrich teacher’s intuitive play experience. To effectively facilitate play in a preschool setting, it is essential to appropriately formulate pedagogical goals based on the children’s level of play development and their needs, and then align one’s actions accordingly. Thus, reflection can be considered one of the factors determining pedagogical competence in supporting play in kindergarten.

Testing this hypothesis could serve as a direction for future research.

Limitations. A limitation of this study is the self-selected nature of the sample (it did not include teachers who are uninterested in supporting children’s play or who prefer an outsider position toward play). The data collection procedure assumed that teachers would independently select and submit videos of joint play for the study, which may not fully reflect the broader picture of play support in a given classroom. As a direction for future research, it would be valuable to complement video analysis with an independent external assessment of the quality of play-support conditions in the classroom. Additionally, the study did not account for institutional factors (such as organizational culture, institutional values, or the specifics of methodological support and teacher training), which may influence teachers’ play support strategies and level of reflection.