Introduction

Russia is losing its position in the ranking of countries in terms of scientific research, the shortage of young scientific personnel is increasing, and the number of university academic staff is decreasing 1. PhD students are the talent pool of both academic staff and university teachers. At the same time, they report low levels of psychological health and well-being, high levels of stress and mental disorders (Sverdlik, 2024), and other difficulties such as balancing work and research, preparing and publishing articles, and a lack of academic skills (Zhuchkova, Terentev, 2024). The relationship with the academic supervisor is one of the most important factors influencing PhD students' motivation, well-being and dropout intentions (Sverdlik et al., 2018).

Relationship and academic supervision style

Studies of the relationship between PhD students and their academic supervisors show that the supervisors play an especially important role in predicting the PhD students’ well-being and success. An assessment of the effects of three sources of social support (supervisor, peers, and relatives) on positive emotions, perceived progress, and intention to continue studying showed that supervisor support was the only factor that significantly predicted PhD students' academic outcomes (De Clercq et al., 2019). PhD students with moderate social support were more likely to intend to drop out than those with high support (Cornér et al., 2024).

PhD students value academic integrity, constructive feedback, open communication and collaborative working with their supervisors. They prefer supervisors who foster caring relationships to those who focus on instrumental roles (Roach, Christensen, Rieger, 2019). Supportive academic supervision has a positive impact on doctoral students' creativity by encouraging academic engagement and fostering social connections (Zhang et al., 2024).

Many classifications of academic supervision styles have been proposed (Gruzdev, Terentev & Dzhafarova, 2020; Mainhard et al., 2009). The most well-developed approach to motivation and the study of motivating and demotivating interaction styles is self-determination theory (SDT) (Ryan, Deci, 2017). We will use the typology developed within the SDT framework, which distinguishes different supervisor interaction styles based on the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs (BPNs) (Devos et al., 2015; Ryan, Deci, 2017). These needs are considered sources of intrinsic motivation. Accordingly, these needs are categorised as either supportive or frustrating of BPNs for autonomy (feeling in control of one's actions), competence (feeling effective in one's actions) and relatedness (feeling accepted by others). Previously, the main focus of research has been on autonomy-supportive and controlling (non-punitive and punitive) styles of academic supervision (Richer, Vallerand, 1995).

PhD students who successfully completed their studies felt that they had received more support from their supervisors, departments, and peers for their BPNs (Litalien, Guay, 2015). Support for BPN during PhD studies fosters the development of a scientific identity linked to career aspirations (Meuleners, Neuhaus, Eberle, 2023). In a model of PhD student support, BPN for competence is supported through structure and BPN for relatedness is supported through involvement (Devos et al., 2015). Several studies have suggested that the three BPNs play different roles: autonomy and competence support are important for the motivation and well-being of PhD students (Shin, Goodboy, Bolkan, 2022; Marchuk, Gordeeva, 2024), while relatedness is important for the desire to pursue an academic career (Meuleners, Neuhaus, Eberle, 2023).

There is evidence regarding the role of gender among PhD students. Support for the three BPNs is related to mental health in PhD students of both genders; the most important of these is support for the BPN for competence. PhD students require a structured academic environment that provides clear expectations and communication, constructive feedback, attentive guidance, and support to maintain motivation and effort. Women may also benefit from an approach that fosters autonomy rather than control (Wollast et al., 2023).

Well-being, burnout and perseverance of PhD students

Two categories of resources contribute to the well-being of PhD students: personal resources, such as self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation, and environmental resources, such as support from supervisors, departments, families, peers, institutions and public policies (Acharya, Rajendran, 2023). Environmental factors that can negatively affect the psychological health and well-being of PhD students include isolation and difficult relationships with supervisors, colleagues and the department (Jackman, Sisson, 2022).

Burnout is one of the indicators of ill-being. In both the classical model by C. Maslach and S. Jackson and the updated model by W. Schaufeli, burnout is characterised by two components: exhaustion and depersonalisation (cynicism and mental distance). Dissatisfaction with academic supervision, the frequency of contact and the quality of motivation are related to the experience of academic burnout and dropout intentions (Cornér et al., 2021; Devine, Hunter, 2016; Shin, Goodboy, Bolkan, 2022).

The perseverance shown in pursuing a chosen goal is related to success in the activity and the intention to continue learning (Gordeeva, Sychev, 2024), which is also relevant to PhD students. Research in self-determination theory (SDT) shows that autonomy support and basic psychological needs (BPN) satisfaction underpin the intention to continue learning (Litalien, Guay, 2015; Wollast et al., 2023). However, the relationship between academic supervision styles based on BPN satisfaction or frustration and PhD students' perseverance and willingness to put effort into scientific work remains unclear.

The study aimed to identify the relationship between academic supervision styles that support or frustrate PhD students' BPN and their motivation, perseverance, academic burnout, and well-being.

Hypotheses: Autonomous and structuring academic supervision styles that support BPN for autonomy and competence will be directly related, predicting autonomous motivation, perseverance and well-being, while negatively predicting burnout. Chaotic and controlling styles that frustrate BPN will contribute to controlled motivation and burnout.

Participants and methods

Participants: Participants in the study in winter 2023 were 142 PhD students of Russian universities (M=28,8; SD=5,2), including 54% women: 30% in the first year, 31% in the second year, 24% in the third year, and 14% in the fourth year (Marchuk, 2025).

Methods: The academic supervision styles were assessed by the author's Questionnaire on Academic Supervision Styles (QA2S) (Gordeeva, Marchuk, Butenko, 2024), which was based on the SDT and a study of several similar instruments. Consisting of 14 statements, it assesses four styles: two that support BPNs for autonomy and competence (autonomous and structuring), and two that frustrate these BPNs (controlling and chaotic). Respondents rate the following statements on a 5-point Likert scale «My supervisor…»: «welcomes my contributions to our discussions» (autonomous); «controls me quite tightly» (controlling); «helps me make sense of the scientific ideas, problems, and research» (structuring); and «criticises my work and ideas without explaining how to correct them» (chaotic). The skewness and kurtosis of the questionnaire scales were within ±1,5 (from -0,90 to 1,25 and from -0,71 to 1,47, respectively). Confirmatory factor analysis was used to test the four-factor structure of the questionnaire, showing an acceptable fit with the data (χ²(68) = 131, χ²/df = 1,93, p < 0,001, TLI = 0,903, CFI = 0,927, SRMR = 0,085, RMSEA = 0,081 [0,060, 0,102]). The reliability of this and other questionnaires is summarised in the table.

The PhD students’ motivation was assessed using The Universal perceived locus of causality scales (UPLOC) (Sheldon et al., 2015). Respondents were asked to rate 29 statements on a 5-point Likert scale in response to the question, «Why are you currently working on your thesis/research?». The questionnaire consists of six scales: two scales assess autonomous motivation: intrinsic motivation («Because I enjoy it») and identified motivation («Because I feel this is my calling»), three scales assess controlled motivation: positive introjected motivation («Because it is important for me to be successful»), negative introjected motivation («Because I feel ashamed to give up this activity and look unsuccessful») and external motivation («Because I started this activity and now I have to continue») and one scale assesses amotivation («Honestly, I don't know. I feel like I'm just wasting my time»).

Well-being was assessed using the Russian version of the PERMA Profiler questionnaire (Isaeva, Akimova, Volkova, 2022). The study comprised 17 questions ranging from 0 (“none of the time/not at all”) to 10 (“all of the time/ extremely”) and six scales, five of which corresponded to the PERMA well-being model: positive emotions («How often do you feel joyful?»), engagement: («How often do you lose track of time while doing something you enjoy?»), relationships («To what extent do you receive help and support from others when you need it?»), meaning («To what extent do you lead a purposeful and meaningful life?»), accomplishment («How often do you achieve the important goals you have set for yourself?»).

The Academic Burnout Scale (Cornér et al., 2021) comprises cynicism and exhaustion scales, as well as ten statements that are rated on a seven-point Likert scale. «I have difficulties in finding any meaning to my doctoral dissertation» (cynicism) and « I feel overwhelmed by the workload of my doctoral research» (exhaustion).

Perseverance was measured using a modified version of the 6-item persistence scale (Gordeeva & Sychev, 2024), which was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale. Example statement: «I achieved a goal in scientific work that required several years of effort».

Data analysis was carried out using the RStudio and Jamovi statistical packages.

Results

Table

Descriptive statistics, scale reliability, correlations between questionnaires scales

|

Parameters |

Autonomous |

Controlling |

Structuring |

Chaotic |

M(SD) |

Cronbach’s α |

|

Autonomous |

— |

3,96(0,9) |

0,85 |

|||

|

Controlling |

- 0,22* |

— |

1,65(0,63) |

0,70 |

||

|

Structuring |

0,70*** |

- 0,22* |

— |

3,48(1,01) |

0,85 |

|

|

Chaotic |

- 0,55*** |

0,47*** |

- 0,63*** |

— |

1,73(0,71) |

0,70 |

|

Intrinsic |

0,24** |

- 0,20* |

0,16 |

- 0,29*** |

3,81(0,98) |

0,93 |

|

Identified |

0,32*** |

- 0,31*** |

0,23** |

- 0,33*** |

3,78(0,91) |

0,90 |

|

External |

- 0,14 |

0,33*** |

- 0,07 |

0,29*** |

2,29(1,06) |

0,83 |

|

Amotivation |

- 0,36*** |

0,38*** |

- 0,21* |

0,36*** |

2,24(1,16) |

0,94 |

|

Burnout |

- 0,27** |

0,33*** |

- 0,15 |

0,28** |

3,33(1,33) |

0,88 |

|

Cynicism |

- 0,27** |

0,29*** |

- 0,20* |

0,31*** |

3,29(1,59) |

0,85 |

|

Exhaustion |

- 0,22* |

0,29*** |

- 0,08 |

0,20* |

3,36(1,43) |

0,85 |

|

Perseverance |

0,28*** |

-0,21* |

0,22** |

-0,19* |

3,55(0,70) |

0,72 |

|

Engagement |

0,38*** |

-0,14 |

0,29*** |

-0,14 |

6,99(1,84) |

0,78 |

|

Meaning |

0,40*** |

-0,23** |

0,26** |

-0,20* |

7,01(2,07) |

0,89 |

|

Accomplishment |

0,43*** |

-0,28*** |

0,34*** |

-0,30*** |

7,13(1,62) |

0,79 |

|

PERMA |

0,36*** |

- 0,24** |

0,21* |

- 0,22* |

6,86(1,48) |

0,92 |

Note. * – p < 0,05, ** – p < 0,01, *** – p < 0,001.

Autonomous and structuring styles are positively related to each other, but negatively related to their opposites. The same applies to chaotic and controlling styles.

The autonomous style is directly related to autonomous forms of motivation (intrinsic and identified) and negatively related to amotivation. The structuring style is only related to identified motivation, reflecting motives of personal value and connection to goals, and is negatively related to amotivation. Chaotic and controlling styles are negatively related to autonomous motivation and directly related to external motivation and amotivation. Autonomous and structuring styles are directly related to perseverance, while controlling and chaotic styles are inversely related.

Autonomous and structuring styles are directly related to well-being and its three dimensions: engagement, meaning and accomplishment. The controlling and chaotic styles are negatively related to accomplishment, meaning and the general well-being, and are not related to engagement. The autonomous style is negatively related to burnout and its components, whereas the structuring style is only related to cynicism. The controlling and chaotic styles are positively related to burnout and its aspects.

The study found no statistically significant differences in the evaluations of academic supervision styles according to the gender of the PhD students (t = 1,52, p = 0,131; t = 0,32, p = 0,753; t = 2,13, p = 0,035; t = -1,19, p = 0,238). Additionally, no statistically significant differences in the variables (figure ) by year of study were observed.

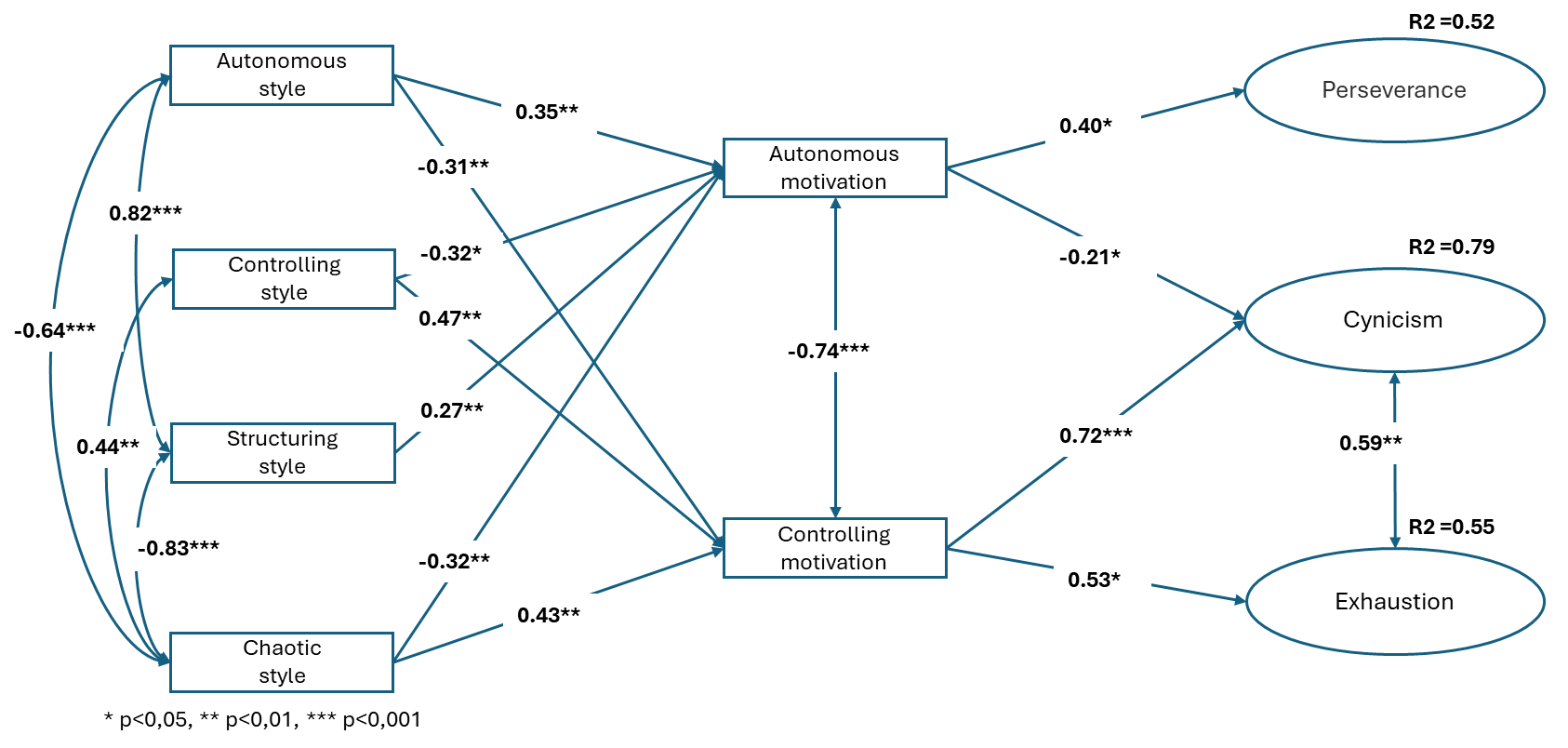

To test the assumption that styles and motivation influence burnout and perseverance, a structural model was constructed (see figure). The estimation of this model showed an acceptable fit to the data: χ² = 1644; df = 1153 (χ²/df < 3); p ≤ 0,001; CFI = 0,898; TLI = 0,887; SRMR = 0,076; RMSEA = 0,057; 90% confidence interval for RMSEA: 0,050–0,063.

As the structural model shows, an autonomous academic supervision style positively predicts autonomous motivation (both intrinsic and identified) and negatively predicts controlled motivation (both external and amotivation). The structuring style predicts autonomous motivation. The controlling and chaotic styles are negative predictors of autonomous motivation and positive predictors of controlled motivation. Autonomous motivation positively predicts perseverance and negatively predicts cynicism, whereas controlled motivation predicts both aspects of burnout. These two types of motivation mediate the effects of academic supervision styles on the dependent variables.

Discussion

The styles associated with BPN for autonomy demonstrate the greatest predictive power, which correlates with SDT's general view of the key role of this need in activity. The total number of style effects on the studied variables suggests that environmental factors should first be changed by eliminating unproductive interaction styles (controlling and chaotic), and secondly by teaching interaction styles that support BPNs.

Preferences for BPN supportive supervisory styles for the PhD students’ internal outcomes under consideration are consistent with data from a study of PhD student exhaustion and dropout intentions, which showed that positive aspects of interactions with supervisors include advice and training, psychological support, protection, honest interaction and feedback, and a working relationship characterised by interest and enthusiasm (Devine, Hunter, 2016).

The styles that frustrate PhD students’ BPNs (controlling and chaotic) are undesirable because they include demotivating aspects of academic supervision. These aspects correlate with study data that showed the negative effects of a lack of responsibility, interest, trust and organisation, as well as overly critical and demanding behaviour, a lack of communication and good treatment, and an inability to advocate for the interests of PhD students or provide mentoring (Devine, Hunter, 2016).

On average, PhD students highly appreciated supervisors using autonomous and structuring styles as opposed to controlling and chaotic styles. This may indicate that relationships are generally built harmoniously despite external obstacles in academic alliances, such as supervisors' lack of professional development and high workloads (Biricheva, Fattakhova, 2021).

Training academic supervisors in mentoring can improve the institution of academic supervision. This training should include the use of motivating styles, reducing the use of frustrating BPNs and demotivating interaction styles, and providing feedback in terms of both academic research and relationship management (Devine, Hunter, 2016; Schmidt, Hansson, 2018).

A limitation of the study is its cross-sectional nature, which does not allow us to be certain of the causality of the associations found.

Prospects for future research could include studying preferred styles at different stages of PhD studies and in different socio-demographic settings, as well as studying the effectiveness of interventions and training that teach supervisors about interaction styles.

Conclusion

Support from supervisors of BPN for autonomy and competence is important for PhD students' current scientific activities, in which BPN in relatedness plays a secondary role. However, it is probably more important for long-term effects. Autonomous motivation and perseverance are associated with autonomous and structured styles of academic supervision, while controlled motivation, amotivation and burnout are associated with controlled and chaotic styles. Academic supervision style is an important predictor of autonomous and controlled motivation, perseverance and well-being, or conversely, burnout, in PhD studies. As autonomous and structuring styles are the most favourable for PhD students, mastering these styles, as well as other ways of supporting BPNs, could be a focus for advanced training programmes for academic supervisors at universities.