Introduction

In the context of modern educational policy, as reflected in the Federal State Educational Standards (FSES) across all levels of education, the issue of organizing joint learning activities acquires particular importance. The FSES for primary, basic, and secondary education (NOO, OOO, SOO) all explicitly highlight the system of universal communicative actions as a component of interdisciplinary learning outcomes. These include students’ abilities to formulate and adopt a common goal, collectively plan actions to achieve it, distribute roles (considering the preferences and abilities of all participants), negotiate, discuss both the process and the outcomes of joint work, plan the organization of collaboration, and choose appropriate methods of joint action (On Amendments to the Federal State..., 2022; On the approval of the Federal State..., 2021a; On the approval of the Federal State..., 2021b).

In the FSES for basic general education, it is specifically noted that “mastery of the system of universal communicative learning actions ensures the development of social skills and emotional intelligence in students” (On the approval of the Federal State..., 2021b). As V.V. Rubtsov and I.M. Ulanovskaya point out, “social interdisciplinary outcomes… are simultaneously both a result and a condition for the development of the basic (communicative-reflexive – author’s note) abilities characteristic of this (primary school – author’s note) age” (Rubtsov, Ulanovskaya, 2022). This position directly continues L.S. Vygotsky’s ideas, which maintain that higher forms of human activity “are initially realized through social interactions and as modes of interaction between subjects engaged in joint activity” (Ageev et al., 2023) .

The interconnection between social interaction and learning, and the role of specially organized joint activity in learning and development, have been most thoroughly and consistently developed in the Russian psychological school of V.V. Davydov – V.V. Rubtsov. According to the principles of this school, the process of setting and solving a learning task is associated with the formation of a specific cognitive-learning action directed at identifying a significant relation or a general principle underlying the structure of an object or phenomenon. A necessary condition for the emergence of such an action is the purposeful organization of joint educational activity, in which the subject content is introduced through a system of shared learning actions: coordination, planning, and structuring of interaction between students and adults, and among students themselves; transformation of adult-directed actions; and modeling of new forms of joint action.

It is particularly important that the “discovery” of essential relationships within the subject domain is mediated by the modeling of possible modes of interaction and the integration of individual participants’ actions into the structure of collective activity. As demonstrated by V.V. Rubtsov and A.V. Konokotin (Rubtsov, Isaev, Konokotin, 2022; Konokotin, 2023), this process has its own dynamics, progressing from a “pre-learning obschnost” (characterized by a focus on situational or partial features of an object/phenomenon and on possibilities for individual action) to a true “learning obschnost,” where participants orient themselves toward uncovering essential relations and regularities governing the studied object or phenomenon. This occurs through analyzing modes of interaction, revealing interdependencies among individual actions, and designing pathways to solve a class of problems by building collective action (Rubtsov, Isaev, Konokotin, 2022).

Further development of this problem involves identifying the qualitative characteristics of interactional processes that constitute the internal (integral) features of joint activity—such as mutual understanding, reflection, and communication (Rubtsova, 2020; Salminen-Saari et al., 2021). Of particular interest in this context are studies of the phenomenon of joint attention.

Joint attention is defined as the capacity to concentrate on an object of another person's attention, as well as the ability to direct another's attention toward a particular object (Pöysä-Tarhonen et al., 2021). The scientific community has long moved away from a simplistic, mechanistic view of joint attention as a “relatively elementary process of visually following another’s gaze,” emphasizing that “... the orientation of the head and eyes of another individual is an insufficient source of information about their object of attention” (Zotov, Andrianova, Voyt, 2015).

In a broader sense, joint attention is understood as the ability of two individuals to focus simultaneously on the same external object or event. This basic definition implies that the presence of a triad—“individual 1 – individual 2 – object of attention”—is sufficient for the emergence of joint attention, even in the absence of direct gaze exchange. For instance, P. Mundy emphasizes in his review that joint attention is a fundamental socio-cognitive capacity that involves coordinated concentration of two people on a shared external referent (object or stimulus), forming the basis for shared understanding in communication (Mundy, 2018). Thus, joint attention may take on various forms and levels of complexity, and should not be reduced solely to the classical “triangle” model involving alternating eye contact and shared focus on an object.

In particular, the framework proposed by B. Siposova and M. Carpenter (Siposova, Carpenter, 2019) presents a typology of joint attention as a spectrum of hierarchically related states or levels of "jointness" in attention. The authors argue that joint attention should not be understood as a discrete, binary state (present or absent); instead, it encompasses multiple gradations of attentional engagement—from simple simultaneous looking (common attention) to fully shared attention characterized by mutual awareness. These levels differ in the degree to which partners are aware of each other’s attentional focus and in the nature of the “common knowledge” between them. For example, at a basic level, two individuals might be looking at the same object without being explicitly aware that the other is doing the same—this can be considered common attention without overt communicative coordination. Nevertheless, even such a situation meets the criteria of joint attention, as both individuals are engaged in a shared perceptual field.

Building upon these theoretical positions allows for a broader conceptualization of the joint attention phenomenon. For instance, in a study by S. Schroer et al. (Schroer et al., 2024), using dual eye-tracking in naturalistic environments, it was shown that “parent–child” dyads are able to coordinate attention to the same objects without exchanging deliberate signals. The authors demonstrate that joint attention arises from the dynamics of sensorimotor interaction, rather than solely from intentional cues. These findings align with the view that joint attention during online interaction is manifested through the synchrony of gaze directed at shared objects.

Currently, two types of joint attention are commonly distinguished:

- Bottom-up joint attention, where “the localization of another person's attentional focus is influenced by gaze direction, body position, and the presence of visually salient objects” (Shevel, Falikman, 2022);

- Top-down joint attention, where “the key factor is information about events experienced by the person, regardless of visual salience in the field of view” (Shevel, Falikman, 2022). That is, top-down joint attention relies on “contextual knowledge relevant to the communication situation, such as awareness that a given object is new or significant to the interlocutor” (Zotov, Andrianova, Voyt, 2015; Smirnova, 2020). This idea is further developed by A. Schvarts, who explicitly notes that the emergence of joint attention is closely linked to the construction of a shared semantic foundation for joint action (Shvarts, 2018; Shvarts, Abrahamson, 2024).

As T.M. Shevel and M.V. Falikman point out, “the mechanism of joint attention forms the basis for sharing common information and goals during collaborative tasks, as well as for understanding the intentions and desires of the other person; therefore, its interpretation may also become decisive in identifying the focus of the other’s attention” (Shevel, Falikman, 2022).

A review of studies on social interactions using the eye-tracking method, conducted by A.V. Konokotin, N.Ya. Ageev, I.A. Dubovik, and G.I. Kalinina (Ageev et al., 2023a), showed that, first, oculomotor activity data can serve as a meaningful indicator of the emergence and dynamics of reflection and mutual understanding among participants in joint activity. Second, joint attention, as recorded through oculomotor analysis, may be used as an indicator of participants’ inclusion in the shared semantic context of collaborative activity—signaling their transition to a new level of interaction, coordination, and planning of joint actions in the process of solving a common task.

In this regard, the main goal of the present empirical study was to investigate the characteristics and dynamics of oculomotor activity among participants engaged in collaborative activity at different stages of the development of educational interactions.

Multiplayer online game “Ether Noise”

The multiplayer online game “Ether Noise” is based on the concept of a diagnostic methodology for assessing the ability to design collaborative actions, originally implemented in the group task “Perimeter” (Akopova, Glazunova, Gromyko, 2020).

According to the storyline, a team of players (available in two versions—2-player or 4-player mode) receives the following instruction upon entering the game:

"Your team has landed on the planet NIBIRU. The planet's inhabitants are extremely aggressive and hostile. Your team must quickly construct a protective perimeter around the base. Each team member starts building from their own corner of the future perimeter. Communication is temporarily unavailable..."

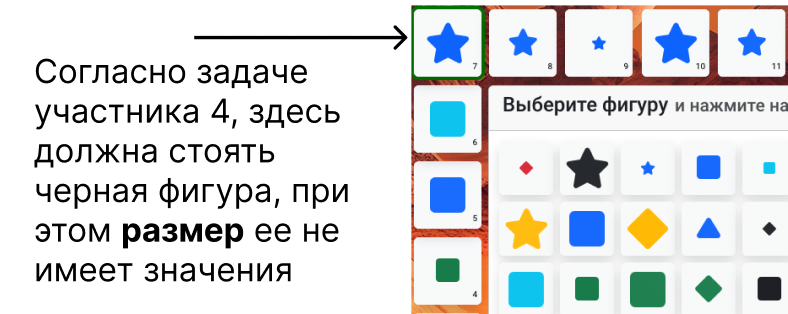

The participants are tasked with building a protective rectangular perimeter around the base using geometric shapes. The working interface of “Ether Noise” consists of an 8x12 rectangular game board displayed on the computer screen. In the center of the board is a pool of 144 geometric shapes, differing in color, shape, size, and animation (Fig. 1).

Each team member is also assigned a unique individual task, which is not known to the other participants. These individual tasks are distributed randomly and require each player to construct the perimeter based on a specific rule known only to them (such as the sequence of figures by color, size, shape, or animation).

A key organizational and functional feature of the “Ether Noise” game is its jointly-distributed form of activity. The gameplay conditions place participants in a situation where the actions of one player are constrained by the actions of another (Fig. 2). Thus, the goal can only be achieved through coordinated teamwork. This creates a special task for the players: to explore ways of organizing collaborative activity, find grounds for dividing tasks, and then integrate and coordinate their efforts within a shared endeavor (Ageev et al., 2023b).

The basis for combining shapes and determining their order relies on identifying genus–species relationships. Participants are not merely asked to perform a classification based on comparing objects and assigning them to predefined categories. Rather, they are expected to reconstruct the essential (genus–species) relationships that govern the coordination and alignment of object properties, in order to form new categories whose properties are defined by the activity’s internal logic. This aspect makes the task inherently educational: its content is the concept of genus–species relations, and the game itself becomes a model of activity-based technology for developing digital educational (and diagnostic) tools.

This organizational and conceptual feature of the game creates a kind of dual-layered situation. The learning-cognitive task of identifying grounds for comparison is mediated by a new challenge—organizing interaction with a partner. The conceptual structure being formed—“genus–species”—is embedded in the system of collaborative interactions.

Fig. 2. Participants' encounter with a conflict situation at the intersection of working areas

At the beginning of the task, each player can only see their own section of the game board. They are able to observe the movement of the highlighted grid frames representing other players, but they cannot see the shapes placed by them. Moreover, communication between players is initially blocked. Once a player reaches the corner—where their moves intersect with those of another participant—they gain access to the chat window and are also allowed to see the figures placed by others in the room. If one player reaches the corner first and places a new shape, the updated figure becomes visible to others only once they too cross into the shared area.

The game has a 60-minute time limit, monitored via a countdown timer. If the team believes they have completed the task before the time expires, they can press the "Propose to End Game" button. Once all players confirm, the system verifies the perimeter construction and notifies the team of the outcome: Mission accomplished or Mission failed.

Study design and sample

The experiment involving the use of the online game “Ether Noise” was conducted between June and August 2024 at the Center for Career Guidance and Pre-University Education “PRO PSY.” The study sample included 30 adolescents and young adults aged 13 to 20 years (M = 17,11, SD = 2,00; 67% female) from Moscow. Social status was not additionally considered.

Participants were grouped into pairs based on age: 4 pairs of adolescents (ages 13–15 inclusive) and 11 pairs of young adults (ages 16–20 inclusive).

During the game, participants’ oculomotor activity was recorded using the NTrend-ET500 video-based eye-tracking module. This system calculates gaze direction through frame-by-frame analysis of video recordings, enabling tracking of head position, eye movement, and pupil size.

Eye movement was recorded binocularly at a frequency of 500 Hz with an accuracy of 0,4°, at a distance of 50–80 cm from the screen. Calibration was performed before each recording using a 9-point grid. Eye-movement data (fixations, saccades, and blinks) were exported in .xlsx format separately for each participant. These files included the start and end times of each event, as well as the gaze coordinates during fixations (and for saccades, the gaze coordinates at the beginning and end of each event) on the screen (area width: 1920 px, area height: 1080 px) for both eyes. Data processing was carried out using Microsoft Excel, RStudio, and Jupyter Notebook.

To detect the occurrence of joint attention, a custom R script was developed that identified fixations located no more than one grid cell apart, and separated in time by no more than 1 second. The script iterated through one participant’s fixations and searched for corresponding fixations from their partner that met the spatial and temporal proximity criteria. A pair of fixations was marked as synchronous if the spatial distance between their coordinates was within the threshold and the time gap between the end of the first and the start of the second was ≤ 1000 ms. The script also accounted for overlapping fixations (i.e., those occurring at the same time), which were automatically marked as joint if spatially aligned. This procedure resulted in a quantitative list of all joint attention episodes. The approach was based on existing methods in dual eye-tracking studies (Yu, Smith, 2017; Olsen et al., 2017).

Fixations on the inner perimeter of the game interface—containing individual task instructions, chat windows, and figure selection panels—were excluded from analysis. These areas changed dynamically upon clicking the “Make a Move” button, which made it impossible to reliably track joint attention fixations and rendered them irrelevant to the experimental task. Only fixations located on the outer perimeter cells were analyzed.

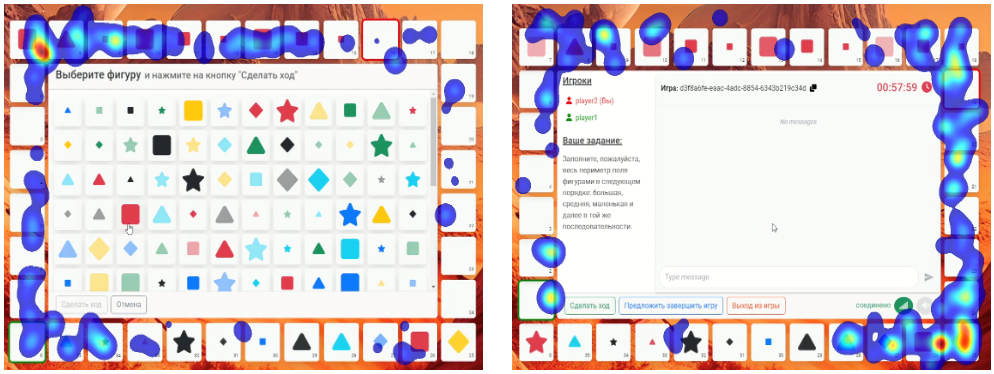

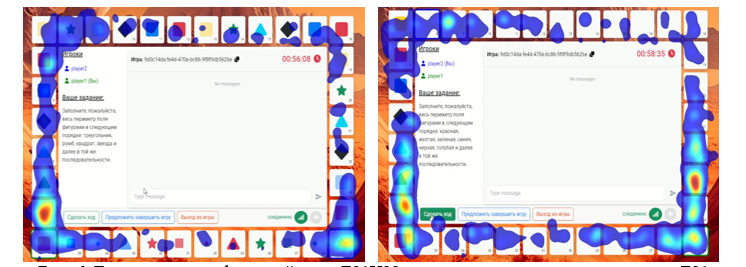

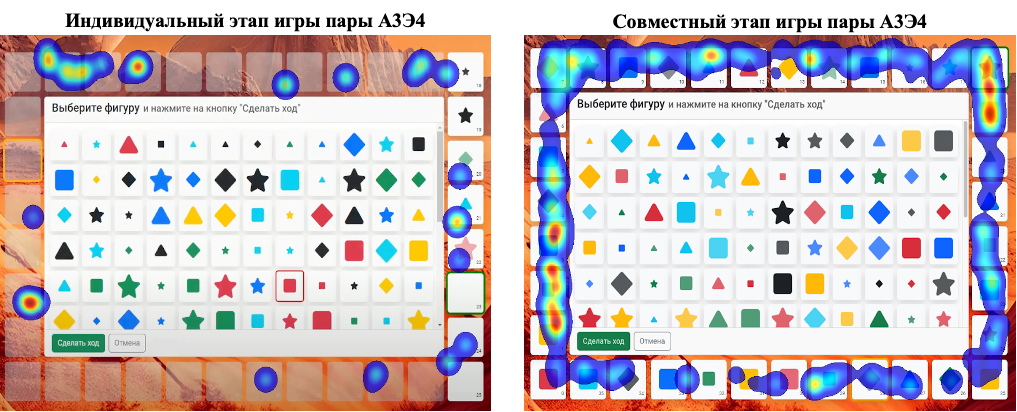

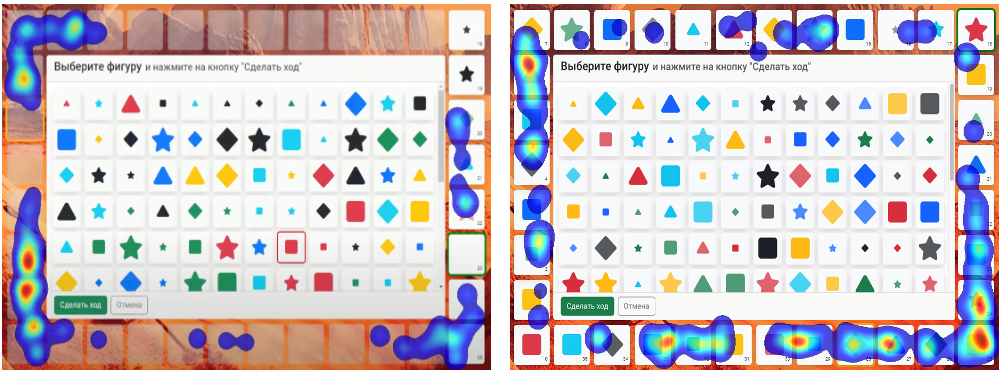

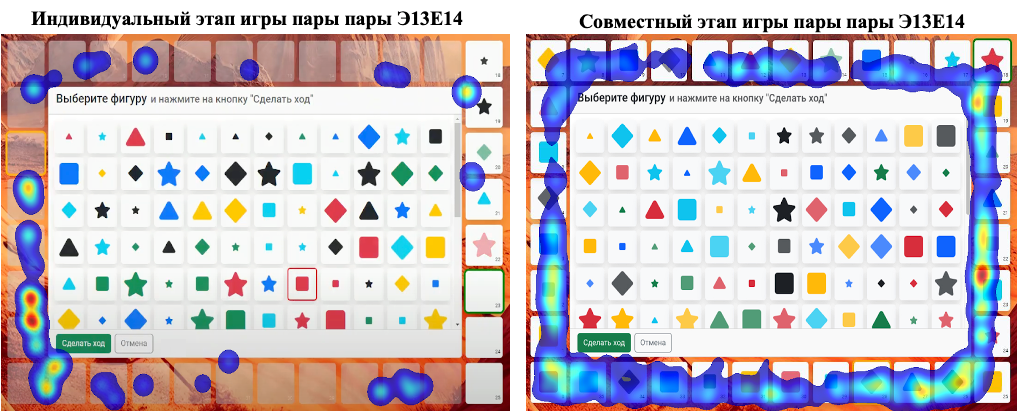

To visualize joint attention fixations, a heatmap-based visualization method was used, highlighting areas of elevated attention. Each heatmap displayed color-coded blobs representing all joint attention fixations during various stages of gameplay within a pair. The color gradient (from blue to red) indicated the frequency of joint fixations in a given area, while the blob diameter reflected fixation duration. The heatmaps were generated using a custom Python 3.12 script. The set of figures displayed along the perimeter and side representations during individual stages did not reflect the actual fill-in for each pair, but rather served as an example.

Quantitative data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software. The following statistical methods were applied:

- Descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation);

- Wilcoxon non-parametric t-test (for within-sample comparisons under non-normal distributions).

The version of “Ether Noise” used in this experiment was designed for 2 players. All participants used identical ASUS monitors with a resolution of 1920 × 1080 px connected to desktop computers. Once equipment installation, participant positioning, and eye tracker calibration were verified, participants were not allowed to leave their seats, move their heads, or communicate verbally. According to the experiment protocol, communication was only allowed via the in-game chat, which became accessible after participants reached the corner of the perimeter.

Analysis and discussion of research findings

The analysis of the dynamics of joint action formation (i.e., different modes of interaction) between participants during the collaborative problem-solving process in the multiplayer online game “Ether Noise” was conducted through a qualitative examination of screen recordings. These recordings allowed for tracking the actions performed by participants while constructing the perimeter (i.e., placing geometric shapes on the field), as well as their communication through chat messages.

The problem-solving process for each participant pair was divided into two stages:

- Individual Stage, which combines pre-organizational and pseudo-organizational modes of interaction (in line with the typology of V.V. Rubtsov and A.V. Konokotin). This stage is characterized by a specific subject of communicative interaction—the search for a solution based on the possibilities of individual action. At this stage, the partner’s actions are not perceived as contributing to the solution of the task. Essentially, this phase involves solving the “object-related task” (i.e., constructing the perimeter) exclusively on the basis of the individual rule assigned to each participant at the beginning of the game.

- Joint Stage, which combines organizational and reflexive-analytical interaction modes. This stage is marked by the emergence of a shared goal focused on the planning and organization of joint activity (interaction), and the coordination of individual actions within a structure of collaborative action aimed at solving the common problem—constructing the perimeter by integrating individual rules.

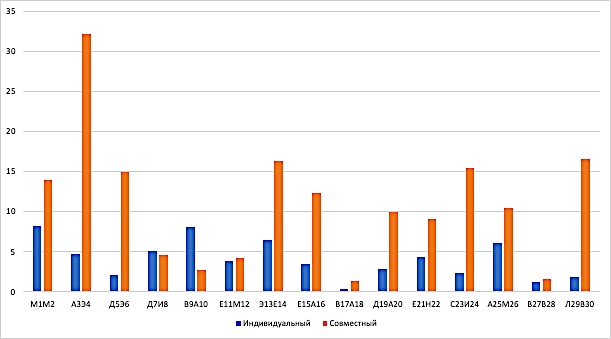

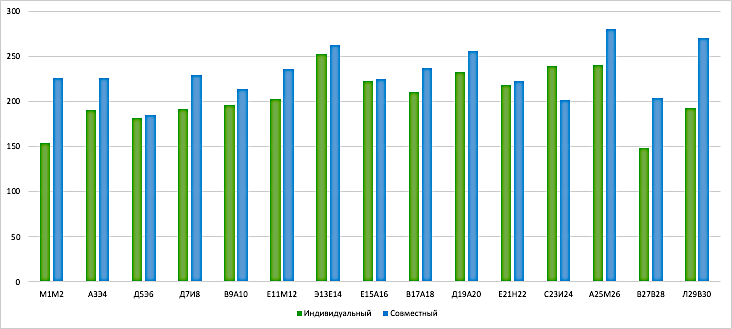

Following this division into individual and joint stages, the oculomotor data of each participant pair were analyzed separately for each stage. The table presents data on the number, median duration, and frequency of joint attention fixations observed.

Table

Parameters of joint fixations for the individual and joint stages of the game for each pair of players

|

Pairs |

Median duration of joint fixations, ms |

Frequency of joint fixations, units per minute |

||

|

Individual stage |

Joint stage |

Individual stage |

Joint stage |

|

|

М1М2 |

154,0 |

226,0 |

8,2 |

13,9 |

|

А3Э4 |

190,0 |

226,0 |

4,7 |

32,1 |

|

Д5Э6 |

182,0 |

185,0 |

2, |

14,9 |

|

Д7И8 |

192,0 |

229,0 |

5,1 |

4,6 |

|

В9А10 |

196,0 |

214,0 |

8,1 |

2,7 |

|

Е11М12 |

203,0 |

236,0 |

3,9 |

4,2 |

|

Э13Е14 |

252,0 |

262,0 |

6,5 |

16,3 |

|

Е15А16 |

222,0 |

225,0 |

3,5 |

12,3 |

|

В17А18 |

210,0 |

237,0 |

0,4 |

1,4 |

|

Д19А20 |

232,0 |

256,0 |

2,8 |

9,9 |

|

Е21Н22 |

218,0 |

222,0 |

4,4 |

9,1 |

|

С23И24 |

239,0 |

202,0 |

2,4 |

15,4 |

|

А25М26 |

240,0 |

280,0 |

6,1 |

10,4 |

|

В27В28 |

148,0 |

204,0 |

1,3 |

1,6 |

|

Л29В30 |

193,0 |

270,0 |

1,8 |

16,5 |

A comparison was made between the frequency and median duration of joint attention fixations for each pair during the individual and joint stages of the task (see Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). The fixation duration parameter allowed us to demonstrate that the observed phenomena were not merely random artifacts or express fixations (i.e., shorter than 150 ms) (Theeuwes, Burger, 1998; Radach, Heller, Inhoff, 1999; Velichkovsky et al., 2000; Pannasch et al., 2001; Godijn, Theeuwes, 2002), but instead represented fully legitimate oculomotor events, reflecting the cognitive activity and its dynamics within the participants.

The diagrams reveal that:

- In 13 out of 15 participant pairs, the frequency of joint fixations increased during the joint stage.

- In 14 out of 15 pairs, the median duration of joint fixations on the same area of interest also increased at the joint problem-solving stage.

It was found that during the individual stage, participants exhibited processes of reflection related to understanding the rule their partner was using to construct their own sequence of geometric figures. Their gaze direction moved between several key areas:

- The partner’s working area;

- Their own working area;

- The area of their individual task.

For example, in pair A3E4, whose “starting sides” were located on opposite long sides of the perimeter, fixations during the individual stage—including the longest ones—were concentrated in the area where participants encountered their partner’s rule (see Fig. 5).

In pair E21H22, whose “starting sides” were on adjacent edges (bottom and left), the longest fixations were again located in the area of overlapping activity (see Fig. 6).

These patterns provide substantial evidence that the fixations reflect participants’ awareness of the difficulty arising during task execution and their attempts to overcome it by analyzing the principles upon which each participant builds their sequence of shapes. Furthermore, during this period, communication begins to emerge, with participants explicitly drawing one another’s attention to these difficulties (Husnutdinova et al., 2023), which is accompanied by the appearance of joint fixations.

At the same time, it is important to note the relatively low frequency of joint fixations at this stage, despite their comparatively long durations (see Fig. 7 and Fig. 8). This suggests, on the one hand, that participants were still primarily acting individually and planning based on their own representations of how to solve the task; and on the other hand, that a gradual transition was underway—from solving the individual problem to joint planning of actions and coordination in pursuit of a common goal.

Similar to individual fixations, joint fixations at the individual stage tended to concentrate in areas where one participant's actions began to disrupt the rule used by the other participant. These were the moments where they would “encounter” one another and begin to negotiate interaction, establish a shared goal, model a collaborative solution, and coordinate their individual efforts (see Fig. 7 and Fig. 8). Thus, joint fixations at the individual stage were closely linked to reflective processes, aimed at understanding both one’s own and the partner’s grounds for action in the context of collaborative work.

Further quantitative analysis of the data revealed the following:

- The mean frequency of joint attention fixations per pair during the individual stage was 4,08, whereas during the joint stage it reached 11,02;

- The mean median duration of joint attention fixations per pair during the individual stage was 204,7 ms, increasing to 231,6 ms during the joint stage.

Statistical analysis using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test revealed significant differences in both the frequency of joint attention fixations per minute and the median fixation duration between the individual and joint stages (T = 10,5, p ≤ 0,01). These results indicate the emergence of stable joint attention in participant pairs during the transition from the individual to the joint stage of the task.

It is important to emphasize that the emergence of joint attention in the context of distributed collaborative activity arises, on the one hand, as a consequence of participants encountering constraints on their individual actions, which lead to processes of reflection, communication, and action exchange. On the other hand, it becomes the very foundation for further development of these processes, as well as for planning, modeling, and coordinating new modes of interaction through sustained mutual understanding (Rubtsova, Ulanova, 2014).

This idea is further supported by the qualitative analysis of heatmaps during the joint stage (see Figs. 7, 8, and 9).

Here, joint fixations appear across the entire perimeter, exhibiting a continuous rather than fragmented pattern. They reflect a shared tracking process, where both participants follow the same perimeter zones throughout the task. We also observed variability in the “patterns” of joint fixations across different participant pairs. According to qualitative video analysis, discontinuous joint attention patterns (as in Fig. 8) were typical of pairs that implemented a cooperative mode of interaction. Conversely, pairs engaging in reflexive-analytical interaction—where individual operations were integrated into a shared structure—tended to show more coherent and sustained joint fixations (as in Fig. 9).

However, we found no consistent correlation between the type of joint activity organization and the structure of joint fixations displayed in the heatmaps. Nor was there a reliable association between the frequency or duration of joint fixations and the mode of interaction (organizational vs. reflexive-analytical). This may be due to the fact that modes of interaction are complex formations, or what V.V. Rubtsov and A.V. Konokotin describe as “emotionally-meaningful unities”, which cannot be fully captured through psychophysiological indicators alone, such as eye movement data.

What truly matters is the subject of communicative interaction—that is, the basis on which collaborative action emerges: either as cooperative alignment of operations, or as modeling of joint action through analysis of the relationship between task content and interaction structure.

Nevertheless, oculomotor data did prove useful in distinguishing between individual and joint forms of activity, allowing us to identify forms of jointness based on differences in the emergence and structure of joint attention. This indicates that various modes of participant interaction indeed form a kind of functional unity that requires complex cognitive processes: planning, modeling, organizing, coordinating, and monitoring collaboration as the means for solving the shared task.

Additionally, a focused analysis was conducted on video recordings from two pairs (B9A10 and D7I8) in which a decline in joint attention fixation frequency was observed during the transition from individual to joint stages. In both cases, the participants adopted a cooperative mode of interaction. They identified a common task (comparing individual action rules), exchanged their task texts via chat, and agreed to proceed “together.” However, their cooperation took the form of sequential individual execution, as shown in the following exchange:

“I’ll do my task... You just change my pieces to the color you need.”

“Ok, go!”

Based on the above, we can conclude that oculographic data collected during participants’ collaborative activity—specifically, the duration and frequency of joint fixations, as well as the spatial areas of gaze concentration—can serve as informative indicators, first, of the cognitive processes emerging during task performance (primarily reflection), which are related to analyzing and evaluating the principles and regularities guiding participants’ transformation of the task’s problem space; and second, of the transformations in the very modes of interaction employed by participants throughout the course of their joint activity.

Conclusion

Based on the quantitative data analysis and the qualitative interpretation of heatmaps reflecting joint attention fixations during different stages of the educational task (individual and joint) in the multiplayer online game Ether Noise, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- The emergence of joint attention between participants engaged in distributed collaborative activity—centered on solving a cognitively significant task—occurs primarily in situations where individual actions are limited by task constraints. This prompts reflective and communicative processes aimed at overcoming these constraints through analyzing the task content and developing new modes of interaction. These interactions involve coordinating individual operations within an evolving shared structure of joint action.

- Joint attention functions as the foundation for the development of new forms of interaction between participants. It enables the emergence and maintenance of stable mutual understanding, which is grounded in a shared conceptual grasp of the learning task and allows for effective joint planning and execution.

- Oculomotor indicators—specifically, the frequency and duration of joint fixations, as well as the spatial distribution of gaze—can serve as meaningful markers of underlying cognitive processes, particularly reflection. These indicators also provide insight into dynamic changes in the forms of interaction employed by participants during collaborative work.

- Eye-tracking data offer a reliable basis for distinguishing between individual and joint forms of activity organization, especially in the process of internalizing and mastering the conceptual content of a learning task. These distinctions are critical in identifying shifts in cognitive engagement and collaboration.

The “Ether Noise” multiplayer online game demonstrates significant potential (pending appropriate standardization and validation procedures) as a diagnostic tool for assessing universal communicative learning actions in adolescents and young adults at the basic and secondary education levels.

This potential stems from the structural-functional properties of the instrument itself: the game does not offer a static “snapshot” of individual abilities (as is often the case with traditional questionnaires and self-report methods aimed at assessing social skills), but rather provides a dynamically unfolding process, in which a specialist can directly observe how communication, action exchange, reflection, and mutual understanding develop in a real-time educational context.

Such a setting allows researchers and practitioners to access and support the students’ zone of proximal development, as conceptualized in cultural-historical psychology, by providing opportunities for observing and guiding emerging processes of joint meaning-making and collaboration (Konokotin, 2021).