Introduction

The concept of a learning task (hereafter referred to as LT) is one of the key notions in the theory of educational activity by D.B. Elkonin and V.V. Davydov (Elkonin, D., 1989; Davydov, 1996, 1999; Engeström, 2025; Gennen, 2023; Chaiklin, 2019). An LT is a whole system of assignments. Unlike concrete-practical tasks, which focus on achieving a specific result, an LT stimulates the student to search for general principles and methods applicable to a broad class of problems (Rubtsov, Elkonin, Zuckerman, Ulanovskaya, 2024). Its resolution results in changes within the acting subject (Elkonin, D., 1989), that is, the emergence of a functional field of actions performed using this new method (Nezhnov, 2007). The distinctions between LTs and particular tasks, as well as the stages of their formulation and solution, are most comprehensively presented in the works of V.V. Davydov (Davydov, 1996) and further developed by V.V. Repkin (Repkin, Repkina, 2018).

Solving an LT typically spans multiple lessons and defines the holistic act of educational activity. It is understood as a transition and overcoming of the form of solving a concrete-practical task — that is, as an Act of the Development of Action (Elkonin, B., 2020).

An LT is a ‘trigger mechanism that encourages a person to invent and devise new methods of action, thereby restructuring their understanding. In this sense, learning tasks must constantly be present in developmental education’ (Gorbov, Zaslavsky, Morozova, 2015, p. 19). Various methodological versions of LT formulation are presented in educational courses at different levels (Engeström, 2025; Gorbov, Zaslavsky, Morozova, 2015; Perevozhchikova, Vasiliev, 2015; etc.).

From the earliest attempts to implement the theory of educational activity in practice, it has been noted that transmitting the technology of LT formulation is a crucial aspect of preparing teachers transitioning to an activity-based strategy in education (Davydov, 1999; Guruzhapov, 2006; Perevozhchikova, Vasiliev, 2015; ‘Trainer-Technologist — A New Pedagogical Position’, 2025).

It has been repeatedly discussed that teachers find it difficult to master the new instructional technology. As V.A. Guruzhapov wrote: ‘Teachers often lack a clear understanding of the learning task itself, as well as its place in the learning activity. There is no developed culture of formulating learning tasks’ (Guruzhapov, 2005, p. 83).

The problem of transferring this technology remains relevant today, despite the emergence of various active teacher training methods (Vasiliev, Vakhromeeva, 2024; ‘Trainer-Technologist — A New Pedagogical Position’, 2025; Vorontsov & Lvovskiy, 2022; Waermö & Broman, 2024). The teacher’s activity in the LT formulation setting remains largely unexplored, as researchers’ attention has long been focused on students’ development.

The key to exploring this issue is found in the works of D.B. Elkonin (Elkonin, D., 1989), B.D. Elkonin (Elkonin, 2020), and G.A. Zuckerman (Zuckerman, Venger, 2010), who insisted that ‘...the formation of a learning action must be understood as A SINGLE joint1 action of the teacher and the student (or a group of students), and not as two “separate” actions of student and teacher (“pedagogical action” and “student action”)’ (Elkonin, 2020, p. 30).

In joint action, orienting toward another’s actions simultaneously guides one’s own actions (Elkonin, 1989), even though in fully joint activity, only the adult truly acts, by picking up on the child’s signals. Only that form of guidance in which the adult interprets the child’s signals as their initiative can be considered joint action (Zuckerman, Venger, 2010).

In participatory observation, it is important to understand what engages the teacher in unfolding the LA2 — ‘...what intrigues him, not just what is required of him,’ writes B.D. Elkonin (Elkonin, 2020, p. 32).

He also highlights that understanding joint action presupposes identifying the conditions for coherence between students’ and teachers’ positions, and describing the situations in which they become co-subjects of a shared action. The first such condition is the teacher’s position that welcomes the emergence of student initiative and allows it to strengthen and grow (Obukhova, Zuckerman, Shibanova, 2022).

The goal of this work is to refocus the perspective of researchers of learning activity from the student to the teacher in order to seek answers to the following questions: What professional challenges shape the teacher’s work in the situation of formulating a learning task? What is the orienting basis (Galperin, 2023) of their actions? What drives the teacher to choose one path or another in an underdefined situation?

What difficulties and risks influence the success of the class’s joint movement? A comparative analysis of video recordings of two successful LT formulation lessons taught by the same teacher in different classrooms was conducted by G.A. Zuckerman (Zuckerman, 2007). She showed how a master teacher, with different instructional designs, built equally effective learning cooperation.

The task of this study is to examine not always successful or partially successful cases of organizing such interaction to find answers to the questions posed above.

The hypothesis is that in the situation of learning task (LT) formulation, the complex and contradictory nature of the orientations guiding teacher action is revealed to the greatest extent. The complete system of orientations presented in instructional manuals requires trial and further development under the concrete and shifting conditions of the lesson. In this process of trial, the teacher’s own supports for initiating joint action are formed. An additional hypothesis is that a necessary condition for maintaining the connectedness of student and teacher positions in a situation of joint action is the teacher’s distinctive authorial stance as the creator

Materials and Methods

Participants and Research Procedures

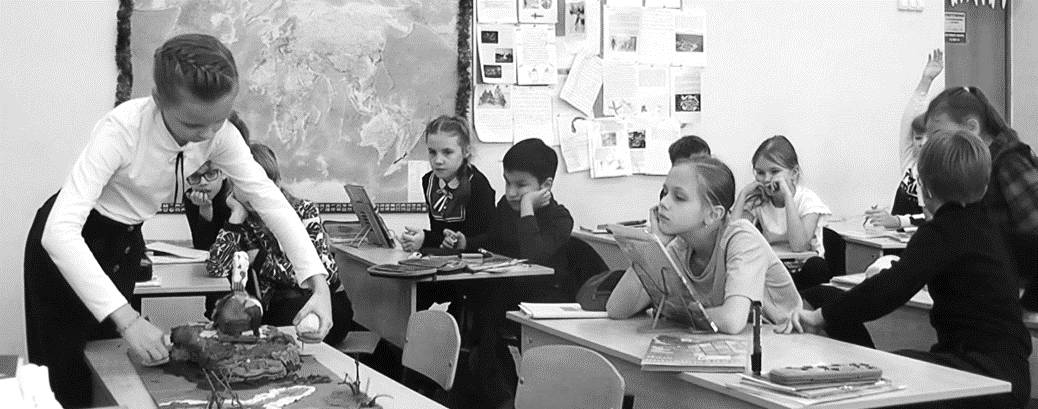

The study involved participatory observation followed by video analysis of seven lessons devoted to the formulation of the same learning task (LT) in third-grade classrooms. These lessons were conducted by five female teachers (aged 28 to 54), each with 2 to 16 years of experience within the Elkonin—Davydov educational system. Three of the teachers were implementing this lesson for the first time; the other two had conducted it on two or more prior occasions. Two of the teachers were recorded teaching in two different classes. The main research method was a case study, within which an in-depth comparison was made of the teachers’ actions in organizing the formulation and initial solution of the LT. The analysis focused on how closely these actions followed the instructional design proposed in the teaching manual, what unexpected situations caused hesitation or unplanned teacher responses, and what teachers relied on when addressing their remarks and questions to students, among other aspects. This kind of analysis demanded that researchers understand “...the real situation as fully and concretely as possible, including its smallest individual features” (Lewin, 2005, p. 79).

The video analysis was supplemented by the results of a survey administered to 20 female teachers aged 23 to 65 who were attending professional development courses. Among them, 10 had prior classroom experience formulating the LT on discovering contour lines, and 10 did not. The teachers read a section of the instructional manual describing the formulation of the LT, then individually drafted a plan for their future actions, after which they answered a series of questions about how this task would be presented in class. The survey aimed to assess the manual’s potential for fostering a preliminary understanding of LT formulation and to identify any differences in how the manual’s content was interpreted by teachers with and without prior experience implementing the LT.

Research Material

The learning task used as the basis for this study involved the discovery of a method for recording information on a map using contour lines — lines representing equal values of elevation, temperature, humidity, etc. — in the “The World Around Us” course for third grade, taught using the Elkonin — Davydov system (Chudinova, Bukvareva, 2025). This is a general method applicable to a broad class of problems that require either identifying or marking various conditions on a map, such as atmospheric pressure, temperature, and so on, or selecting an optimal route that avoids elevation changes.

This LT was particularly well-suited to the research objectives because it clearly separates two stages:

- Problem framing, which leads students to pose the task themselves — namely, the search for a method; and

- Work on solving the task, which includes exploring and discussing the proposed solutions to identify the most effective one.

The LT emerges in the context of solving a concrete-practical problem: determining the shortest route between two points on a map where mountain elevations are not depicted. Students suggest options: traveling directly, going around the mountain depicted on the map, or a compromise between the two. The effectiveness of each option can be assessed by measuring the corresponding path lengths on a 3D model. The impossibility of determining the shortest route from a 2D image leads students to pose a task for discovering a general method for representing elevation on a map.

Students’ proposals are then discussed, analyzed, and transformed, eventually becoming fixed in a model using symbolic representation (contour lines on the map). This constructed model is subsequently tested on other tasks, such as:

- identifying habitats of animals and plants that live under different conditions of humidity and temperature,

- planning ship routes in bodies of water of varying depth, and so on.

Results

A survey of teachers following their independent work with the instructional manual showed that, overall, the manual adequately describes the lesson for setting and initiating the solution of a learning task (LT). After familiarizing themselves with the material, teachers understood the content of the task and were able to schematically envision their version of the upcoming

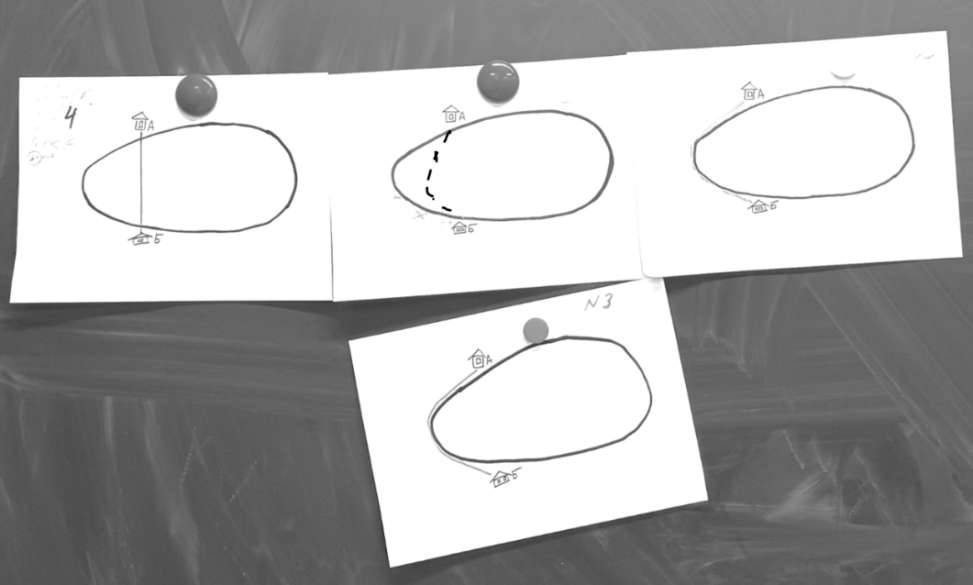

Video analysis showed that the formulation and initial solution of the LT on discovering contour lines5 were carried out in different classes over the course of one or two lessons. The effectiveness6 of the task formulation varied. At the stage of the practical task — whose solution was supposed to reveal a contradiction and the need to denote elevation on a map — the effectiveness of the teacher’s actions directly depended on how the task was phrased. If the teacher, when articulating the task, did not explicitly state (verbally or on the map) that there was a mountain between points A and B (three cases), students generated a multitude of unproductive versions, and the discussion became prolonged. If the task formulation essentially matched the one proposed in the instructional manual, three solution options emerged (see Fig. 1).

The next stage, according to the manual, involved identifying the contradiction between the visible path length on the map and the actual distance. The diversity of students’ proposed solutions stemmed from the lack of information about the mountain’s height and shape.

Student A: It’s very long here (draws a straight line).

Student B: Yes, it’s REALLY long here, the mountain could be THIS tall. But here, it would be this tall (gestures). And climbing here would be really easy. So, like this, right?

A: Yeah, that’s okay (draws a line around the edge of the mountain).

Not all children experienced doubt, so the next instructional task was to create a clash of perspectives by comparing the results of the group work. Most teachers asked the students themselves to carry out this comparison, though in one class the teacher summarized the outcomes independently.

According to the logic of the manual, selecting the correct solution required presenting the students with a three-dimensional model of the mountain. At this point, in 3 out of 7 cases, the teacher lost student attention by allowing continued verbal discussion without showing the model. Moreover, in 6 out of 7 cases, students voiced the idea: “Only a fool climbs a mountain,” or “It’s easier to go around…” — which necessitated returning to the original task. More experienced teachers responded quickly: “What task are we solving — finding the easier or the shorter route?” Less experienced teachers allowed students to become entangled in debate, which failed to produce a clear contrast between the length and “ease” of a path.

Fig. 1. Options for solving by four groups a concrete practical problem

Path-length comparisons were also conducted in different ways. Sometimes students instantly came up with an effective method.

Teacher: So, which route is actually correct? Let’s take a look. (pulls out the model)

Students: What’s that? It’s a mountain! (noise). It’s huge… That was a top-down view… We didn’t know it was that tall. That was a plan view.

T: Yes, maybe it was an optical illusion… How can we know if the mountain is tall enough that we need to…

S: Go around it.

T: And to do that, what do we need to do?

S: Measure it with a string7 or something else…

In other classes8, students needed between 2 and 12 minutes to find a solution (see Fig. 2). When this stage dragged on, teachers made different choices: some allowed students to continue proposing and testing ideas until a solution was found (4 out of 7), while others offered a hint — a measuring ribbon (2 out of 7).

Comparing the path lengths allowed students to choose the correct option. Those who had chosen the “incorrect” route justified themselves by saying, “But we didn’t know the height of the mountain!” At that moment, experienced teachers returned students’ work and suggested they think of how to indicate elevation on the map diagrams (in three lessons). Other teachers missed the moment when students had essentially formulated the problem themselves and prolonged the discussion — perhaps waiting for the exact wording of the goal they expected to hear. As a result, students’ attention would drift. Group-based exploration of a method quickly reoriented students back to the task.

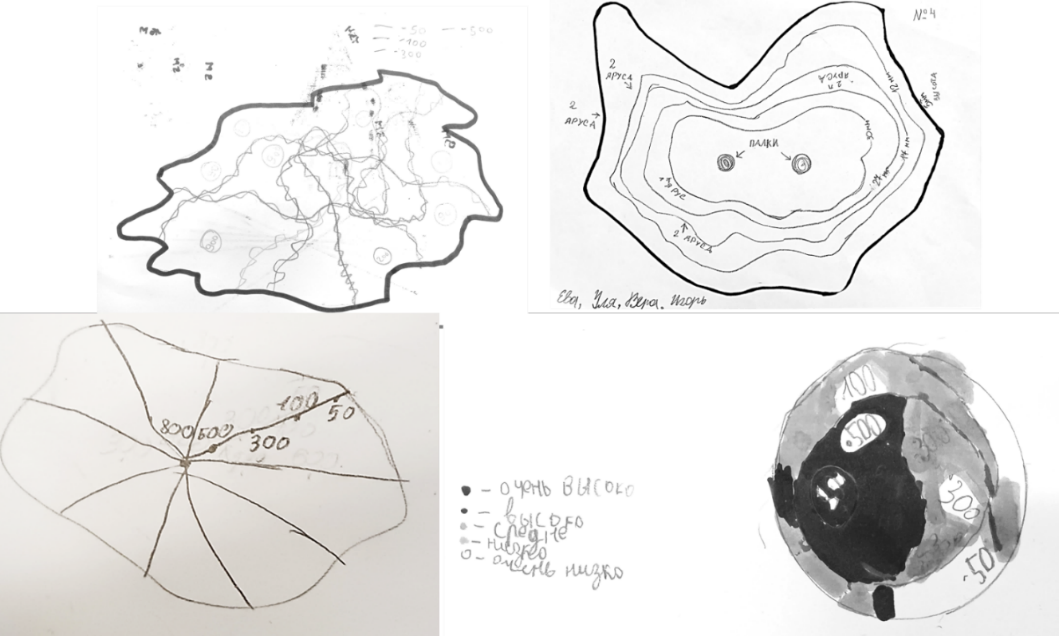

One of the most difficult stages for teachers was the discussion of solution options proposed by the groups, during which a general method was to be identified (see Fig. 3). The organization of this discussion depended on the number, diversity, and quality of the students’ proposed solutions. It was more challenging for those who had not established a clear sequence for reviewing solutions during group work and instead followed a formal rule — starting with the group that was ready to respond first. In such cases, it became impossible to follow a substantive logic that built upon earlier ideas and enabled their transformation.

A comparison of teacher questionnaire responses with the actual implementation of this step turned out to be revealing. One of the survey questions asked teachers to determine the order in which proposed solutions would be discussed and to justify their choice. Beginner teachers showed more variability in their sequencing choices (four out of six possible sequences) but provided more formal or no justifications at all. In contrast, experienced teachers made more content-based decisions: “from mountain drawing, to color, to lines,” or “first what doesn’t map well, then what doesn’t convey the mountain’s shape, and then what’s closer to the truth,” and so on.

The challenges of this stage were also due to the fact that not all student ideas could be anticipated, and teachers had to find ways to analyze these ideas spontaneously during the lesson 9.

In one of the lessons, students did not come up with the idea of marking elevations on the map diagram using numbers — a decision that could have served as a starting point for the final stage of discovery. One class settled on using color to indicate elevation — something they had previously seen on physical maps but had not understood at the time. In such cases, teachers adjusted their strategy and shifted the discussion toward analyzing a ready-made contour map, so that students could grasp the meaning of contour lines and learn to use them for problem solving.

In one case, the teacher’s lesson design significantly deviated from that proposed in the instructional manual10. Aiming to ensure maximum student independence, the teacher intended that in the second stage, the children themselves would place identical numbers on the map, which could then be connected with a line. However, framing the task in such a way that students would immediately record a series of identical numbers — rather than a single number representing an assumed mountain height at a single point — was only possible through direct control of the students’ hands11, due to their lack of a method for measuring elevation at different points.

Teacher: The elevation around this perimeter is 10 meters. Please enter the data on your sheet — five or six data points.

Since the idea of placing multiple numbers on the map had not emerged from the students themselves, they were unable to develop it further. The students lost the sense of the teacher’s remarks and shifted to guessing his intentions.

Teacher: There’s too much data. Can we somehow reduce it, but still understand what the mountain’s elevation is in each area? Your suggestions. How can we combine this data?

Student: We should add it up... Multiply it… Measure it...

Teacher: Why? We need to represent it. How can we combine these elevations?..

In some discussions — those which could be qualified as successful based on their outcome — participants demonstrated close attention to shared actions and full mutual understanding. They responded to each other’s remarks almost instantly. Remarks became shorter, more interlinked. The pace accelerated.

Student 1: Maybe it’s not a tall mountain?!

Student 2: Or maybe it is tall!

Student 3: It’s impossible to know!

Teacher: Why?

Student 4: We don’t know what kind of mountain it is! It’s just something drawn… (gestures a circle).

Teacher: So what are we missing on this map to know for sure?

Students: The height of the mountain!

In such moments, the teacher could respond not only to students’ words but even to the facial expressions of silent students.

Teacher: Right! What do the numbers on this map represent?

Student: The elevations of the peaks.

Teacher: The elevations of the peaks. Okay. But something’s bothering Sonya. What is it, Sonya?

Sonya: There are too many.

Student: Too many of the same!

By involving a silent student in the discussion, the teacher provoked the development and support of that student’s thought by others and made that child’s actions meaningful for themselves.

At such moments, the teacher’s attention was entirely focused on the students’ actions. One could observe that the teacher would temporarily, or partially, lose awareness of their own behavior — for example, starting to fiddle with their collar — while remaining acutely sensitive to what was happening with the students.

During such moments of the lesson, when addressing the class, teachers often used inclusive pronouns like “we” and “us”: “We’ve understood that this is important, right?”, “Can we consider this method effective?”, “That’s not an argument. How are we going to flatten the mountain?” and so on. At other points in the lesson (such as at the beginning or end, or in situations that could not be qualified as successful collaboration), the language shifted more frequently to “I,” “you,” or “we with you.”

If, when responding to students’ utterances, the teacher already knew their next move and was not prepared to diverge from it, then the meaning of the students’ preceding remarks did not become clear to them. For example, in the case below, the teacher elicited a range of ideas about why a character might choose to take a detour, but then directed the class toward a single, pre-planned option.

Teacher: Swamp. Snakes. Lake. And everything else you’ve mentioned. What else could be an obstacle?

Student: Mountains.

Teacher: Mountains. And now — attention! Anything could be there. At the very least, mark the mountains on the map.

The analysis of recordings showed that not all teachers were able to let go of additional, previously set goals during the lesson involving the formulation of a learning task — for instance, correcting students’ utterances for grammatical accuracy or requiring them to use a particular verbal formulation.

Since two teachers conducted the lesson twice in different classrooms, changes made to the lesson plan after the first implementation were recorded. These changes involved rewording the initial task, altering the sequence for reviewing solution options, increasing their openness to student suggestions, and giving students more opportunities to carry out their own trials. After the first lesson, teachers actively sought feedback, attempted to evaluate their own actions, and looked for correspondences between those actions and the students’ substantive activity.

Discussion of results

The data obtained confirm the main and additional hypotheses of the study.

The complex and contradictory nature of the orienting systems that guide teacher action manifests most clearly in the situation of formulating a learning task. Just like a driver who must simultaneously operate the vehicle’s systems and navigate the road, the teacher, when organizing the formulation and solution of a learning task, must hold together two systems of orientation. One is the unfolding of the task’s subject-matter logic over time; the other is the intellectual-emotional landscape of the class. Neither of these systems can be fully predetermined in advance. Even though the teacher knows the final outcome of the search (a general method) and the approximate paths toward it, the solutions proposed by students demand immediate comprehension and the elaboration of a possible logic for their transformation. This confirms the observations of G.A. Zuckerman (Zuckerman, 2007).

The intellectual-emotional landscape of the class, much like the “military landscape” described by K. Lewin (Lewin, 2001), is in constant flux, and the teacher continuously assesses the current moment with varying degrees of success. The key orienting factors that influence the teacher’s choices include not only the students’ engagement in the search or, conversely, their loss of interest in the task, but also the extent to which the whole class participates in the inquiry, the time spent on discussion stages, and so forth.

The orienting systems described above can come into conflict in the teacher’s mind. For example, when the search for a method to measure the direct and roundabout paths drags on, teachers often feel a strong urge to stop it — after all, this has already been “covered” in math lessons, yet for some reason, the students don’t recall it now. However, the students are clearly engaged in the process. “Should I continue the discussion or stop it and give the children a hint? This isn’t the main point right now, and we won’t have enough time for the core task,” one teacher reflected after conducting the lesson.

Thus, teacher actions in the context of learning task (LT) formulation are inherently experimental. It is fundamentally impossible to structure them solely on the basis of a third-type orienting basis (Galperin, 2022). The issue is not that “everything looked perfect on paper, but someone forgot the ravines…” (L. Tolstoy), nor is it that the material and its mode of introduction fail to meet the “requirements of the method for solving learning tasks” (Davydov, 1999, p. 4). The instructional method is described with sufficient clarity to allow the teacher to build a lesson plan. Already at the planning stage, the teacher takes into account the students’ characteristics and abilities, the configuration of the classroom, the materials and tools used for formulating the task, prior “commitments,” and so forth. Yet, during implementation, these orientations shift again: students’ specific suggestions define the trajectory of the unfolding interaction, and the materials reveal previously unrecognized properties. In this experimental process, the teacher develops their own scaffolds for initiating jointaction, as evidenced by the “revisions” made to the lesson plan during repeated implementations12.

Approaching the LT situation as joint action between teacher and students allows us to see the mutual orientation sustained by a shared object — an object that is in the process of formation or “revival”: a cultural method of action reappearing in students’ activity as an ideal. The goal and meaning, which originally resided solely in the teacher’s intention, begin to be shared by students through the process of formulating and solving the learning task. What arises is a situational non-fusion-yet-non-separation of the subjects of learning activity. A notable symptom of this on the teacher’s side is the frequent use of the pronoun “we” when addressing the class13.

Other signs of connectedness include the students’ engagement in the discussion, an increase in its intensity, and mutual understanding, expressed through the way utterances build on one another. The condition for maintaining this connectedness is the teacher’s sensitivity to student actions — an observation supported by G.A. Zuckerman (Zuckerman, 2007). But it should be added that what matters is sensitivity to student actions specifically in relation to the method being uncovered (or reconstructed). Just as a person’s perception during drawing or writing is concentrated at the tip of the pencil, so too is the teacher’s attention and perception, in successful moments of such lessons, focused on the point where students are transforming the conditions of the task.

Joint action does not arise if the teacher already knows their next response and is unwilling to deviate from it. In that case, student utterances lose their meaning, and the joint situation collapses.

On the teacher’s side, joint action can be understood as Authorial Productive Action (Elkonin, 2019). The teacher is not the author of the cultural model — the method of action. Nor is the teacher typically the author of the instructional method for learning task formulation. Nonetheless, we can speak of a distinctive authorial stance: the teacher as the re-creator of the ideal — the method of action historically fixed in symbolic-cultural forms and reanimated in students’ thinking through the process of solving the learning task.

The construction of the lesson plan and the initial implementation of the LT lesson represent the first movement in this productive action. It involves a “turn in experience,” a transformation of the known cultural method and the instructional technique proposed in the manual into a concrete lesson design for a specific class. At this stage, “implicit constraints on action” (Elkonin, 2019) become explicit and are either overcome or not; potential conflicts in the teacher’s orienting systems are either resolved or remain unresolved.

A learning task (LT) lesson can become a trap for an experienced teacher accustomed to implementing their own designs. In trying to act as the author of the task formulation logic — while departing from the thoroughly tested sequence provided in the manual — the teacher risks entering a situation from which it is difficult to find a way out without resorting to “pushing through” their own intent, thereby suppressing student initiative.

The teacher’s authorship and artistry lie in retaining students’ utterances in working memory and constructing from them a storyline for unfolding the situation, one that aligns with the method being reconstructed. The risk involved, the need to engage all one’s cognitive resources (quick thinking, comprehension, memory span, attention distribution), the challenge of achieving a result, and the fusion with the class that occurs in joint action — all of this captivates the teacher and draws them into the unfolding of the activity. For the teacher, formulating a learning task is a test of professional fitness.

Success in LT formulation, on the teacher’s side, consists not only in the successful engagement of students in inquiry, but also in constructing meaning and internal scaffolds within their own exploratory action. When the teacher becomes aware of the experimental nature of their actions, it generates further questions about the plan and its implementation, prompts corrections, and makes it easier to forgive the almost inevitable flaws that arise in solving such a complex task. This is why the presence of another adult (through participatory observation) enhances the teacher’s awareness and the overall effectiveness of the LT lesson — something noted by other researchers as well (Vasiliev, Vakhromeeva, 2024).

Productive action is impossible without validation by its recipient (Elkonin B., 2019). The affirmation of the teacher’s action that initiates a situation of symbolic mediation is its incorporation into the field of student activity. To borrow the words of B.D. Elkonin, the potential of the teacher’s intent becomes the energy of revival — that is, the reconstruction and appropriation of the general method by the students. This is why signs of students discovering and internalizing the general method of action are so vital for the teacher.

Conclusion

In the design and implementation of an LT lesson, the teacher’s systems of orientation are complex and often contradictory, requiring real-time adaptation during the lesson itself. Through such experimentation, the teacher builds their own supports for initiating joint action. The conditions for maintaining.

What motivates the teacher in the meaningful formulation of a learning task is the inherent risk — and simultaneously, the potential productivity — of authorial action. The hypothesis that only deliberate experimentation leads to developmental progress — for both students and the teacher — has yet to be fully tested.

The empirical findings of this study help to concretize the concepts of joint action (D.B. Elkonin, 1989) and authorial productive action (B.D. Elkonin, 2019). These results and conclusions are significant for the preparation and retraining of teachers pursuing the path of activity-based pedagogy.

Limitations. The study sample size is adequate for the case study method, but the results and conclusions require confirmation and refinement in larger studies.

1 Different authors use the terms joint activity or joint action to denote, essentially, the same phenomenon; an analysis of the terminological distinctions is beyond the scope of this paper.

2 LA — learning activity. of the ideal3 — namely, a method of action that exists, for the time being, in symbolic-cultural forms and is reconstituted by the teacher in the “minds” of the students.

3 The ideal here is used in the sense developed by E.V. Ilyenkov (Ilyenkov, 2006):

"The material is indeed 'transplanted' into the human head—and not merely into the brain as a bodily organ of the individual—first, only in the case that it is expressed in immediately and universally significant forms of language (language here understood broadly, including the language of drawings, diagrams, models, etc.); second, if it is transformed into an active form of human activity with a real object (and not merely into a 'term' or 'utterance' as the material body of language). In other words, an object becomes idealized only where the capacity has been created to actively reconstruct this object (emphasis mine — E.Ch.), relying on the language of words and diagrams—where the capacity has been created to turn 'word into deed,' and through deed, into thing" (Ilyenkov, 2006, p. 21). lesson. According to Fisher’s phi and Cramér’s V criteria, no significant differences were found in the questionnaire responses between the groups of inexperienced and experienced teachers (there was not a single question for which α was less than or equal to 0.05)4. Nonetheless, when reflecting on specific aspects of the future lesson, teachers attributed different meanings to particular actions. Teachers with classroom experience of implementing this task made their choices more reflectively. In contrast, inexperienced teachers tended to choose based on subjective preference (“like / dislike”). Teachers who had experience setting an LT reasoned as follows: “Option 3 is better because the teacher responds to children’s answers without judgment and poses questions that guide the direction of their thinking. It’s horizontal communication,” or “In the third option, I would try to involve the rest of the students somehow. As it stands, it’s just a dialogue with the teacher. Instead of the teacher’s final line, something like ‘and what then?’ would be better.”

4 The data were processed using IBM SPSS Statistics.

5 The actual discovery and consolidation of the method in symbolic form.

6 Since the study did not assess students’ achievements in mastering the method of reading, representing, and using contour lines on map diagrams to solve problems, effectiveness here can only be discussed in terms of indirect indicators—such as the class’s level of engagement in the inquiry, the teacher’s satisfaction with the lesson, students’ emotional responses, and the time spent.

7 The student is referring to comparing lengths by measuring with a piece of string. This method was introduced in mathematics at the beginning of the first year of study.

8 Except for one case, where the teacher chose their own path from the very beginning of the lesson, and this stage was omitted.

9 Instructional manuals, when describing the process of solving a learning task, include possible variants of student responses, but it is not possible to anticipate all of them.

10 Despite the failure of this particular design, an authorial stance on the part of the teacher in designing the logic of task-formulation lessons remains possible.

11 V.A. Lvovsky (2024) writes about the widespread use today of "direct pedagogical actions."

12 Each subsequent task-formulation lesson is always a “repetition without repetition.”

13 Although this was noted in the observation, a definitive conclusion requires analysis of a larger number of casesconnectedness between the teacher’s and students’ positions include both the teacher’s sensitivity to the students’ current actions in relation to the method being uncovered (or reconstructed), and the teacher’s distinctive authorial stance — as the creator of an ideal method of action, historically encoded in cultural symbolic forms and revived in students’ minds.