Introduction

Many authors note that the modern social world is characterised by a high degree of variability and uncertainty about the future. In the psychological space, sharp uncontrollable transitive social changes that alter social conditions and opportunities for life are considered as risk factors of human mental development (Martsinkovskaya, 2019). The modern world is associated with plurality and diversity, where the ‘challenges of modernity’ create wide opportunities for self-determination, while at the same time placing increased demands on a person’s personality in the situation of life choices (Asmolov, 2015). The diversity of society interactions generates a wide variability of individual development trajectories of adolescents’ maturity achievement, including in the conditions of crisis phenomena (Larson, Wilson, 2014). Thus, the modern social world is a diverse space of opportunities and constraints that can dynamically change uncontrollably, creating zones of future uncertainty due to the difficulties of logical justification and prediction of ongoing and potential changes. The key psychological process of adolescence is self-determination, where the surrounding social world acts as a basis for self-discovery. The age-psychological specificity of adolescents’ self-determination is determined by developmental tasks solution (R. Havighurst), that among others include: setting and realization of self-determination in education and career sphere; acquisition of interpersonal communication skills (in particular, relations of friendship and love) in peer group of own and opposite sex; development of new family relations on the basis of liberation from parental care with autonomy and independence. Also important is development of psychological new formation — sense of adulthood (D.B.Elkonin) as a form of self-consciousness expressed in independence and actions ‘as an adult’. (Molchanov, 2024). Stability of the surrounding world, stability and clarity of social guidelines, predictability and predictability of social structures become important conditions for successful socialization and identification. In the modern understanding, the content of identity arises from individual everyday experience, thoughts, feelings, interactions and behavior of individuals and refers to their efforts to construct, maintain and refine their identity. (Grishina, 2025, p. 17). Thus, the events of the changing and unpredictable world around them and the attitude towards them, which are singled out as significant, become important conditions for the development of an adolescent’s identity.

It is known that the social situation of development as an ‘age-specific, exclusive, unique and unrepeatable relationship between the child and the surrounding reality, primarily social’ is the most important component of the child’s mental development (Vygotsky, 2000, p. 903). The nature of the adolescent’s attitude to the social environment, in particular to the events taking place is important to understand the correlation between personality and social situation of development is. As L.S. Vygotsky wrote ‘... a child at different stages of development ... comprehends and imagines the surrounding reality and environment in different ways’ (Vygotsky, 2001, pp. 77-78). Experience as ‘the child’s internal attitude as a human being to this or that moment of reality’ realizes his or her active-action position in relation to the world (Vygotsky, 2000, p. 994; Karabanova, 2024). It can be assumed that individual allocation of personally significant events is a manifestation of the adolescent’s active-action position within the social situation of development, which determines the variability of the influence of the social environment on his/her mental development and well-being.

In adolescence, there is a sensitivity rise to the influences of surrounding world, that can be reflected in the emotional status, as well as affect mental development (Sawyer, Patton, 2018). The experienced emotional states are important for the subjective well-being of adolescents. In the model proposed by E. Diener, the presence of positive and negative affective states, along with life satisfaction constitutes the interrelated content of subjective well-being of a person (Diener, 1984). A large number of studies confirm the role of positive emotions in human life (Walsh, Boehm, Lyubomirsky, 2018). A specific feature of adolescence is the high lability of experienced emotional states: the intensity of experiences and the speed of change of opposite emotional states can be very high (Tolstykh, Prikhozhan, 2015). In this perspective, it is important in the study of adolescents’ emotional states as predictors of subjective well-being not only to analyze the balance of experienced positive and negative effects, but also to study stable emotional states of clinical nature. High levels of anxiety, severity of depressive symptoms, and difficulties in coping with stress can be indicators of a low level of subjective well-being can influence adolescents’ interaction with the social world, and complicate the process of solving the problems of age development.

There is a large number of psychological studies of adolescents who have been in areas of combat operations. However, most of them are aimed at studying the psychological consequences of changes in the living conditions of adolescents due to the participation or proximity of military events. (Aleksandrova, Dmitrieva, 2024; Menshova et al., 2024; Schiff et al., 2012). These are studies of the psychological consequences of direct participation in armed conflicts, the experience of forced migration from zones of constant shelling, etc. They study adolescents that experience losses: the death of people, the experience of loss of material property, the risks of potential threat to their lives, the lives of their relatives and acquaintances, the experience of living in new social, often unfavourable conditions. It is noted that such adolescents often experience stress due to restrictions in the availability of familiar forms of social life: education (e.g., transition to distance learning), places for walks, meetings, entertainment, etc. (Betancourt, 2017). Numerous negative psychological consequences of adolescents’ intersectional experiences with combat experience in emotional, cognitive, and regulatory spheres are highlighted (Samokhvalova et al., 2025). For example, the perception of the world as less benevolent, less belief in luck and conviction in life control, and less positive image of the self was identified in adolescents from Mariupol, Donetsk People’s Republic, who have experienced combat operations, compared to their peers without such experience, are recorded at the level of basic beliefs of the personality (Dolgikh, Almazova, Molchanov, 2025).

The social conditions of living in Sevastopol city in recent years are characterized by increased risks due to the special military operation. Residents of the region face regular air defense activities protecting the area from drones; there are occasional tragic incidents involving loss of life and destruction of certain city objects. External reminders of the proximity of military operations, associated with various time constraints, are also present. The issue of studying the psychological specificity of adolescents living in such conditions becomes relevant to identify the risks to mental development and ways to prevent them.

The aim of the study: to investigate the relationship between significant events identified by adolescents and their emotional status in an unstable social environment in Sevastopol city.

The aim of the study allows us to formulate an exploratory hypothesis: significant events of the last year, identified by adolescents in an unstable social environment, are related to their emotional status. This led us to formulate two research questions:

- Are the significant events of the last year identified by adolescents more determined by age-psychological specificity (in particular, age-related developmental tasks) or by the unstable situation in the region?

- Are the significant spheres and the emotional coloring of identified events related to adolescents’ emotional state?

The following research objectives were identified:

- To analyze the content of significant events of the last year experienced by adolescents;

- 2. To examine the peculiarities of the emotional status associated with significant events of the last year experienced by adolescents;

- To analyze the features of adolescents’ emotional status in relation to various significant events of the last year.

Materials and Methods

The study involved 559 adolescents from Sevastopol from 15 to 17 years old (M=15,7; SD=1,01), studying in grades 9-11 of general education schools, 231 (41,3%) were males. Data were collected in October 2024, in an online form on the Testograph platform, in classrooms with separate seating to maintain confidentiality of responses.

Research methods:

- Author’s questionnaire focused to indicate three emotionally significant events that occurred last year. It was suggested to describe emotionally significant events of the last year in free form.

- DASS-21 (Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21). The level of psychological well-being in the emotional sphere was assessed using the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (Lovibond, Lovibond, 1995; Zolotareva, 2021). The version of the technique used includes 21 items assessed on a 4-point scale by R. Likert.

- SPANE (The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience, SPANE). The technique is aimed at assessing the frequency of positive and negative experiences during the last four weeks and the balance between them (Diener et al., 2010; Rasskazova, Lebedeva, 2020). The 5-point scale of R. Likert was used.

Statistical processing of the data was carried out in the Jamovi 2.3.28 programme.

Results

The first empirical task of the study was to analyze the content of significant events of the last year experienced by adolescents. Based on the analysis of respondents’ answers about the three most significant events of the last year, the group of experts identified 10 main categories of events:

- the sphere of educational activity, including description of school grades, passing exams, end of the school year, change of school, and issues of professional self-determination. At least one event in this sphere was mentioned by 43,3% of adolescents. Examples are: ‘got 4 and 5 in a particular subject’, “passed the exams very well”, “cancellation of the exam/entry to 10th grade without exams”.

- sphere of self-development, focused on self-discovery, development, maturation, personal self-determination. Named by 5,9% of participants. Examples of events described: ‘realization of what is real happiness for me’, “a new outlook on life”.

- the sphere of independent achievements in the field of competitions, achieved personal goals, purchases with one’s own money. Named by of 24,7% of subjects. Examples are: ‘winning a competition in another city’, “winning the championship of Sevastopol city in ...”.

- The sphere of interpersonal relations with peers in the areas of friendship and love. It is noted by 42,0% of adolescents. Examples are: ‘stopped communication with my best friend’, “returned communication with an old friend”, “made new friends”, “found love”.

- the sphere of parental family, including family holidays (birthdays of relatives, joint events, births of family members, changes in relations with parents). Named by 15,9% of respondents. Common examples: ‘all relatives are doing great’, ‘the birth of my brother’, ‘my relations with my parents have become even better’.

- the sphere of travelling and entertainment, including visits to other countries, cities, as well as out-of-town activities. It is noted by 39,7% of participants. Typical examples of statements are: ‘a busy summer with travelling’, “a trip for summer holidays with relatives”, “a trip to Gelendzhik”.

- The sphere ‘holidays’, in which two main events are singled out: birthdays, New Year. Named by 17,7 % of adolescents. Examples of statements: ‘my birthday’, “birthday of the closest person”.

- The sphere of material acquisitions and gifts in the form of phones, laptops, pets, books, etc. is mentioned by 28,3% of adolescents. It occurs in 28,3 per cent of adolescents. Examples of statements are: ‘bought a new phone’, “got a dog”, “bought a computer”.

- The sphere of moving in connection with a change of place of residence. It was named by 4,8% of participants. Examples of statements of the described events in this sphere are: ‘moving to another city’, “forthcoming move”.

- The sphere of loss/death of loved ones, situations of surgery and dangerous diseases. It is mentioned by 6.4% of adolescents. Examples of statements of described events in this sphere are: ‘bombing in May’, “terrorist attack on Uchkuevka”, “on 23 June I worked in an open cafe on Uchkuevka” (the date of the terrorist attack), “death of a close person”, “loss of a close person”.

For each research participant, the number of events according to categories was counted. Table 1 shows the mean and standard deviations of the frequencies of event categories in the whole sample and separately for boys

|

Cathegory |

All (M ± SD) |

Men (M ± SD) |

Women (M ± SD) |

Differences |

||||

|

t |

p |

d |

||||||

|

Education |

0,5± 0,66 |

0,5 ± 0,66 |

0,5 ± 0,67 |

0,097 |

0,923 |

0,01 |

||

|

Self-development |

0,1 ± 0,27 |

0,1 ± 0,31 |

0,1 ± 0,23 |

1,653 |

0,099 |

0,14 |

||

|

Achievments |

0,3 ± 0,59 |

0,4 ± 0,66 |

0,3 ± 0,54 |

2,457 |

0,014 |

0,21 |

||

|

Relations with peers |

0,5 ± 0,71 |

0,4 ± 0,68 |

0,6 ± 0,72 |

–2,539 |

0,011 |

–0,22 |

||

|

Parent’s family |

0,2 ± 0,43 |

0,2 ± 0,42 |

0,2 ± 0,43 |

–0,504 |

0,614 |

–0,04 |

||

|

Travel, entertainments |

0,5 ± 0,68 |

0,4 ± 0,64 |

0,6 ± 0,70 |

–2,804 |

0,005 |

–0,24 |

||

|

Holidays |

0,2 ± 0,51 |

0,3 ± 0,57 |

0,2 ± 0,48 |

1,868 |

0,062 |

0,16 |

||

|

Material sphere |

0,3 ± 0,61 |

0,4 ± 0,66 |

0,3 ± 0,57 |

1,083 |

0,279 |

0,09 |

||

|

Removal |

0,1 ± 0,23 |

0,1 ± 0,20 |

0,1 ± 0,25 |

–1,737 |

0,083 |

–0,15 |

||

|

Lose/death/illness |

0,1 ± 0,26 |

0,1 ± 0,22 |

0,1 ± 0,28 |

–1,104 |

0,270 |

–0,09 |

||

Table 2. Cluster’s centers of quantity of events in groups of cathegories (N = 559)

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

||||

|

Self-development |

2 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

||||

|

Interpersonal relations |

0 |

2 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

||||

|

Hedonism |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

||||

|

Stress events |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

||||

|

Quantity of subjects in cluster |

138 |

104 |

120 |

149 |

48 |

||||

The fifth type is characteristic of 8,6 % of the sample. This group is focused on the topic of self-development and encountered stressful events. The named events are related to the experience of loss, death, illness and focus on self. Let’s denote it as ‘focus on self and negative events.’

Consider cross-sex differences in focus on different types of events. Table 3 shows the distribution of boys and girls by different types of significant events.

Using the χ² criterion, it was found that gender and type on significant events are related (χ²=10,009; p=0,040; Cramer’s V=0,134). As can be seen from the above data, type 1 (self-development focus) is more frequent in boys than in girls, and type 2 (relationship focus) and type 4 (mixed focus) are more frequent in girls than in boys.

In order to determine the peculiarities of the emotional status of significant events of the last year, each event, in addition to the category, was also assigned a rating of the emotional status of the event: — 1 — negative event, 0 — no emotion or neutral, 1 — positive event. After that, a final score was calculated for each participant of the study — the sum of emotion scores of all three events.

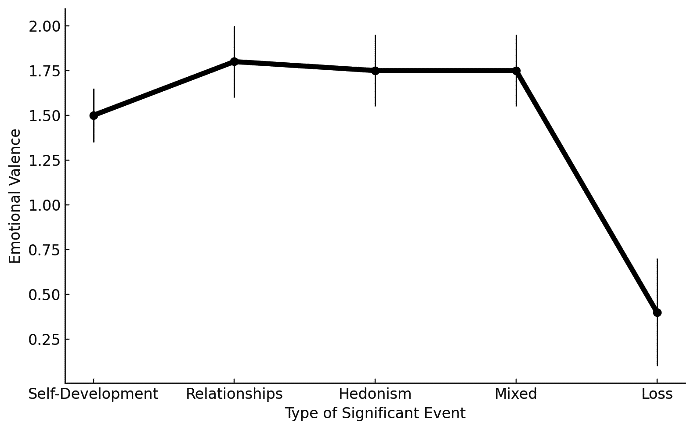

Table 3 shows the mean and standard deviations of the total scores of the emotional status of the events for the study participants of each type and the result of comparison of these scores (one-factor ANOVA analysis of variance), and Fig. 1 shows the scatter of the emotional status scores in different types.

Using Tukey’s post hoc test, it was revealed that the total evaluation of the emotional component of significant events in type 5 (self-focus and negative events) was significantly lower than in type 1 (self-development focus) (MD=–1,201; p<0,001), type 2 (relationship focus) (MD=–1,487; p<0,001), type 3 (focus on self) (MD=-1,408; p<0,001) and type 4 (mixed focus) (MD=–1,383; p<0,001). Thus, we can say that for adolescents, event-oriented on the lived experience, self-development theme and stressful events encountered, less pronounced positive emotional background is characteristic compared to other peers.

Let us analyze the peculiarities of the emotional status of adolescents identifying various significant events of the last year, according to the different types allocated by events. The peculiarities of the emotional status of adolescents were identified using two techniques — SPANE and DASS-21.

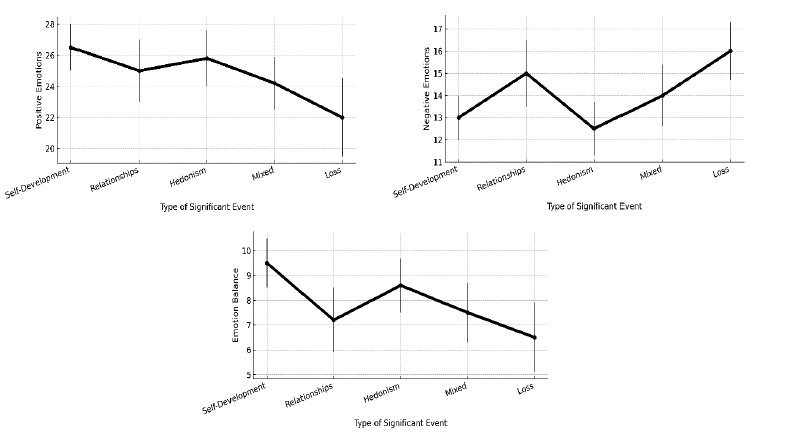

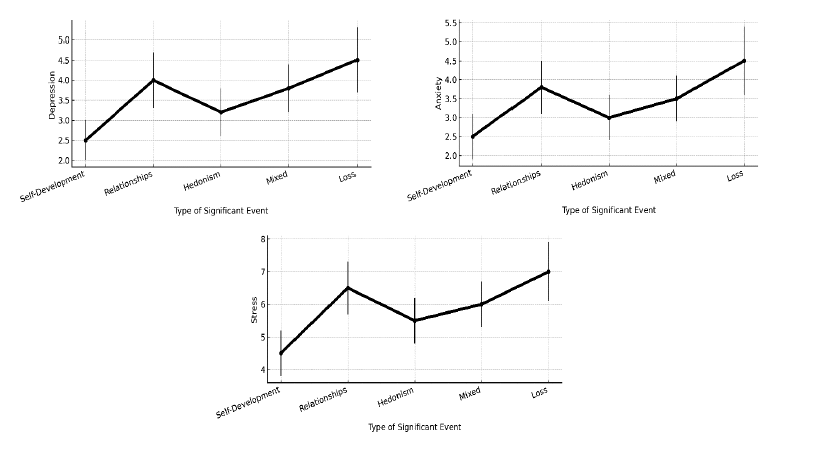

Table 5 shows the mean and standard deviations of scores on the scales of these techniques for adolescents from different types of significant events, a comparison of these scores (one-factor analysis of variance), and Figures 2 and 3 show a graphical representation of the scatter of scores in different types.

Table 3. Distribution of men and women for different types of significant events (N = 559)

|

|

1 type |

2 type |

3 type |

4 type |

5 type |

||||

|

Men |

72 (31,2%) |

37 (16,0%) |

50 (21,6%) |

55 (23,9%) |

17 (7,4%) |

||||

|

Women |

66 (20,1%) |

67 (20,4%) |

70 (21,3%) |

94 (28,7%) |

31 (9,5%) |

||||

Table 4. Comparison of emotional colour in different types of significant events (N = 559)

|

|

1 type (M ± SD) |

2 type (M ± SD) |

3 type (M ± SD) |

4 type (M ± SD) |

5 type (M ± SD) |

Differences |

|||

|

F |

p |

η2 |

|||||||

|

emotions |

1,5 ± 0,93 |

1,8 ± 1,11 |

1,7 ± 0,90 |

1,7 ± 1,06 |

0,3 ± 1,11 |

21,356 |

< 0,001 |

0,13 |

|

Statistical analysis using Tukey’s test (posthoc) revealed that:

(a) negative emotions:

- negative emotion scores of adolescents from type 2 (relationship focus) were significantly higher than adolescents from type 1 (self-development focus) (MD=1,993; p=0,005) and type 3 (self focus) (MD=1,793; p=0,022);

- negative emotion scores of adolescents from type 5 (focus on self and negative events) were significantly higher than those of adolescents from type 1 (self-development focus) (MD=2,442; p=0,009) and type 3 (focus on self) (MD=2,242; p=0,026);

b) emotion balance: emotion balance scores of adolescents from type 5 (focus on self and negative events) were significantly lower than those of adolescents from type 1 (self-development focus) (MD=–4,101; p=0,014) and type 3 (focus on self) (MD=–3,708; p=0,042);

c) depression: depression scores of study participants from type 1 (self-development) were significantly lower than those of adolescents from types 2 (relationship focus) (MD=–4.286; p=0.005), 4 (mixed focus) (MD=–3,501; p=0,015) and 5 (focus on self and negative events) (MD=–5,212; p=0,009);

d) anxiety: anxiety scores of respondents from type 1 (self-development) were significantly lower than those of adolescents from types 2 (relationship focus) (MD=–4,448; p=0,002) and 5 (focus on self and negative events) (MD=–5,984; p=0,001);

Table 5

Comparison of emotional status of adolescents in different types of significant events (N = 559)

|

Emotional status |

1 type (M ± SD) |

2 type (M ± SD) |

3 type (M ± SD) |

4 type (M ± SD) |

5 type (M ± SD) |

Differences |

|||||

|

F |

p |

η2 |

|||||||||

|

Scales of questionnaire SPANE |

|||||||||||

|

Positive emotions |

23,2 ± 4,04 |

22,6 ± 4,29 |

23,0 ± 4,39 |

22,3 ± 4,84 |

21,5 ± 4,90 |

1,666 |

0,157 |

0,01 |

|||

|

Negative emotions |

12,9 ± 4,69 |

14,9 ± 4,35 |

13,1 ± 3,98 |

14,3 ± 4,46 |

15,3 ± 4,78 |

5,636 |

< 0,001 |

0,04 |

|||

|

Balance |

10,3 ± 7,88 |

7,7 ± 7,54 |

9,9 ± 7,38 |

8,0 ± 7,99 |

6,2 ± 7,99 |

4,124 |

0,003 |

0,03 |

|||

|

Scales of questionnaire DASS |

|||||||||||

|

Depression |

3,3 ± 3,99 |

5,4 ± 5,43 |

4,4 ± 4,46 |

5,0 ± 4,79 |

5,9 ± 5,41 |

4,763 |

0,001 |

0,03 |

|||

|

Anxiety |

2,9 ± 4,12 |

5,1 ± 5,12 |

3,7 ± 4,27 |

4,3 ± 4,79 |

5,9 ± 5,52 |

5,637 |

< 0,001 |

0,04 |

|||

|

Stress |

4,9 ± 4,66 |

7,1 ± 5,51 |

5,7 ± 4,52 |

6,4 ± 5,11 |

7,4 ± 5,39 |

4,139 |

0,003 |

0,03 |

|||

e) stress: stress scores of adolescents from type 1 (self-development) are significantly lower than those of adolescents from types 2 (relationship focus) (MD=–4,361; p=0,007) and 5 (focus on self and negative events) (MD=–4,880; p=0,030).

Consider the results obtained. The group focused on self-development, which includes the categories of learning, self-development and achievement, has a more positive emotional status compared to the group of focus on relationships, the group of focus on self and negative events, which significantly outperform the others in the expression of indicators of depression, anxiety, stress, as well as the number of negative evaluations of their lives. Also note that the self-focus group demonstrates a more positive emotional status compared to the relationship focus group and the self-focus and negative events group. Thus, the results demonstrate that the emotional status of adolescents belonging to different groups on named significant events differs meaningfully.

Result discussion

The study analyzed the content of significant events of the last year experienced by adolescents in the city of Sevastopol. The first result was the identification of categories of significant events that adolescents named in free form. These categories include: spheres of educational activities (43,3% of the sample), interpersonal relationships with peers in the areas of love and friendship (42,0%), travel and entertainment (39,7%), material acquisitions (28,3%), independent achievements (24,7%), holidays (17.7%), relationships in the parental family and with relatives (15,9%), loss/death of loved ones, situations of danger (6,4%), self-development (5,9%), and removing (4,8%). As can be seen, the potential risks of adolescents’ social environment due to a special military operation are not reflected for the majority of respondents in the frequency of events highlighted. The significance of events that are frequently indicated — education, interpersonal relations with peers in the field of friendship and love, travel and entertainment, material acquisitions, is largely determined by the stable age-psychological specifics and actual age-specific tasks of adolescent development in accordance with the models of R. Havighurst, and D.B. Elkonin. The solution of such tasks of adolescence development as educational activity and professional self-determination, mastering role models of interpersonal interaction with peers, becoming independent in relations with parents is reflected in the preferred emotionally significant events of one’s own life. Similar results were obtained in a study on student youth of Moscow city after partial mobilization during a special military operation. A high level of psychological resilience of youth to crisis transitivity events was also determined. University students were more focused on the events related to solving the developmental tasks of the period of entry into adulthood than on the stress caused by the events of the special military operation (Markina, Molchanov, 2023). Note that the lack of focus on military actions and their consequences also makes it easier to experience stress existing in a person’s life (Nevryuev, 2022). However, it is necessary tonote a group of adolescents (6.4% of respondents) who highlight events of the sphere of loss/death, situations of surgery and dangerous diseases. It is possible to assume the presence of risks of psychological well-being of adolescents focusing on this group of events.

The analysis allowed us to identify the types of focus on events: ‘self-development focus’, ‘relationship focus’, ‘focus on self’, ‘mixed focus’, ‘focus on self and negative events’. Note the fairly even distribution of adolescents across the different event focuses: the percentages range from 18,6% to 26,7% for four of the five types, except for the smallest group ‘focus on self and negative events.’ The ‘self-development focus’ and ‘focus on self’ groups are in opposition to each other. These groups are similar to the ‘contradiction’ of values of self-exaltation (in particular, hedonism) and values of self-overcoming (benevolence and universalism towards others) highlighted in S. Schwartz’s model of value orientations. In this model, values determine a person’s ultimate desired state (emotional, cognitive) or behavior, including the control function of choice and behavioral evaluation (Schwartz et al., 2012). It can be hypothesized that experiencing values as meaningful influences event-world orientation and recall of important emotional events in the past year.

The group of adolescents who recall more frequently events related to education, self-development and achievement has a more positive emotional status compared to peers orientated towards relationship events and self and negative events. Definition of events of education, self-development, and achievement, consistent with age developmental tasks, is associated with respondents’ positive emotional status. At the same time, focus on interpersonal events — also an important age development task — is associated with a more negative emotional status. This can be explained by adolescents’ different levels of satisfaction with their achievements in different domains. Greater sensitivity and involvement in interpersonal relationships, that lead to greater criticality in evaluating themselves and the events of their lives can be the possible reason. Another explanation for this phenomenon lie in the area of intersex differences. Previous research shows that girls report symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress more often than boys (Shilko et al., 2021). At the same time, girls more often focus on events in the sphere of interpersonal relations. Thus, it is possible to assume that the greater focus on negative events is connected with intersex differences in the reflection of their own negative emotional states. It should be noted that despite the different content of the named events, the emotional status of the groups focused on interpersonal relations or focused on themselves and negative events appears to be similar: the expression of anxiety, depression and stress together with the prevalence of negative emotions. Note that the focus on self and negative events is largely associated with encountering experiences of loss, death, and illness, which naturally increases negative emotional status, while the expression of negative status for the interpersonally oriented group is of concern. Groups of adolescents more oriented towards interpersonal relationships, as well as those focused on self and negative events, need closer examination of their emotional status, which appears to be similar despite the different content of the named events.

Conclusion

Our study aimed to investigate the significant events of the last year identified by adolescents in an unstable social environment and their relationship with their emotional status. Based on the respondents’ answers, the main categories of the mentioned events were identified. The formed event groups mostly are related to adolescence developmental tasks. The idea about the greater role of the age-psychological specifics of adolescence in singling out significant events of the last year in comparison with the instability of the social environment was confirmed.

Certain correlations were obtained between the identified significant spheres and the event colouring, on the one hand, and the emotional state of adolescents, on the other. Special attention should be paid to the group of adolescents focused on events related to the sphere of loss/death, the situation of surgery and dangerous diseases. Psychological support for this group will help reduce the risks associated with difficulties in solving age developmental tasks, as well as increase the overall level of psychological well-being of adolescents experiencing multiple crises in a situation of high uncertainty.