Introduction

Education in BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) and now with BRICS+ (Saudi Arabia, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia, Iran, and Indonesia) operates under the tension between national development agendas and global market imperatives. These nations share challenges such as deep social inequality, colonial legacies, and external pressures to align education systems with neoliberal logics. In this geopolitical scenario, English language education becomes both necessary and a locus of ideological dispute. As a lingua franca, English holds the promise of social mobility and access to global opportunities. However, without a critical pedagogical approach, English teaching risks becoming an instrument of symbolic domination, reinforcing linguistic imperialism and structural exclusion.

In Brazil, this contradiction is acutely felt in the context of Technological Higher Education, where ESP has gained institutional space as part of workforce development strategies. Nevertheless, ESP instruction in Brazil often reflects decontextualized models imported from the Global North, neglecting the social realities and aspirations of both students and teachers. As Tanzi Neto (2015) argues, the teaching of English in Brazil must be rethought as a social and ideological practice, embedded in specific historical, cultural, and institutional contexts. Rather than focusing solely on linguistic skills, ESP should function as a site for critical reflection, identity construction, and collaborative transformative action.

This article responds to that call by examining a teacher education experience rooted in CHAT and organized around the concept of Social Activity (Liberali, 2009). This approach emerges from a Brazilian tradition of Applied Linguistics, which views language education as inherently political and socially situated (Moita Lopes, 2006). It aims to move beyond technicist or neoliberal paradigms, instead promoting agency, collaboration, and critical reflexivity in teacher development. As we emphasize in this article, this requires a reorientation of teacher education programs to center the lived experiences, affective dimensions, and collective engagements of educators.

The present study, developed through Critical Collaborative Research (Magalhães, 2007; Liberali, 2012), involved a series of workshops with five English teachers at a São Paulo Technological Faculty. Grounded in participants’ local realities, the workshops sought to design and reflect on ESP teaching practices that respond meaningfully to students’ sociocultural contexts. By taking Social Activity (Liberali, 2009) as a curricular organizer, the process emphasized the co-construction of knowledge, ethical-political commitment, and the recognition of linguistic education to social transformation (Tanzi Neto, 2021).

Central to this experience is the notion of critical-social transformation as defined in cultural-historical psychology: not simply as structural change, but as the creation of new forms of subjectivity, interaction, shared meaning, and new ways of socially acting in the world. According to Liberali (2012), transformation is inseparable from dialogue, contradiction, and the expansion of what is possible within a given social world. Teacher education, from this perspective, becomes a process of becoming - one that links theory, practice, emotion, and ideology in dynamic ways.

Within the BRICS context, Brazil’s experience resonates with broader efforts to resist educational sovereignty and resist hegemonic pressures. The contradictions explored in this research - between English as empowerment and English as imposition, between local needs and global norms - mirror those faced in India’s postcolonial multilingualism, South Africa’s efforts to decolonize language policy, and China and Russia’s balancing of national identity with internationalization. This article argues that CHAT, when operationalized through grounded, collaborative pedagogical practices, can provide a viable framework for rethinking teacher education in BRICS countries.

In this light, we pose the following guiding question in this study to be reflected and discussed: How can language teacher education in Brazil - when grounded in social activity and cultural-historical principles - contribute to culturally relevant, socially transformative pedagogical practices within BRICS contexts?

English for specific purposes (ESP)

The teaching of ESP, known in its seminal literature by this name, experienced significant expansion starting in the 1960s, within a post-World War II context in which English communication became essential due to the geopolitical position of the United States at the time (Valente & Ribeiro, 2023). This growth was later intensified by globalization and technological advancement, which increased the demand for faster and more purpose-driven language learning (Valente & Ribeiro, 2023). However, in its conception, we understand that this approach, though relevant in professional and academic contexts, can be criticized for its restrictive and instrumental view of language, which may come at the expense of a broader, critical, and transformative linguistic education. To avoid this limitation, Valente & Ribeiro (2023) argue that, precisely because it is not confined to academic and professional matters, it is essential to incorporate social contexts into the teaching of ESP.

By focusing exclusively on the immediate needs of a specific group, such as business professionals, medical practitioners, academia, or tourists, traditional approaches to ESP reduce language to a mere tool for functional communication, thereby neglecting its cultural, historical, social, and affective dimensions. Such an approach can limit learners’ potential to engage with the language in deeper and more creative ways, overlooking aspects such as literature, artistic expression, identity construction, and the transformative power of language. As a result, the traditional view of ESP often relies on a model grounded in functionality and efficiency, ignoring essential sociocultural dimensions of language learning and reinforcing a utilitarian logic that reduces language to a technical tool, stripped of its identity-constructing and political potential. For this reason, it is crucial to consider more contemporary discussions within the ESP framework that incorporates broader social contexts (Diegues, 2025).

In line with this perspective, Bourdieu (2022) argues that language is a field of power - its symbolic power operates as a selective mechanism in society, enabling or constraining speakers’ social and linguistic inclusion. ESP instruction, by targeting specific groups, may inadvertently reinforce existing social and cultural hierarchies. Instead of promoting an inclusive and emancipatory language education, ESP can become a tool for maintaining the status quo, limiting the transformative potential of language.

In summary, ESP or LinFE (Língua para Fins Específicos[1]) approach represents a national evolution of what was previously known in the literature as ESP, and it has increasingly gained ground within academic discourse. It is a constantly evolving approach, with goals and needs that must be addressed in today’s educational and sociocultural contexts.

According to Hutchinson & Waters (1987), British educators and researchers who systematized the ESP approach, ESP should be understood as an approach rather than a product, as it encompasses theoretical assumptions surrounding language and learning. As they assert, “ESP is not a product, but an approach to language teaching which is directed by specific and apparent needs of particular learners” (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987:16).

Almeida Filho (2015) complements this understanding by defining "approach" as a set of ideas, knowledge, beliefs, and principles regarding what language is, what foreign languages are, and how language learning and teaching take place. This includes conceptions about human nature, the classroom environment, and the roles of teachers and students in the teaching-learning process. We align with this perspective, and we understand that all the teacher’s actions in the teaching-learning process reflect their underlying approach, from course planning to classroom delivery.

Hutchinson & Waters (1987) also emphasize that ESP developed in phases, undergoing a series of stages that evolve at different paces depending on the specific national and educational contexts. To understand this historical trajectory, they outline five key stages that contributed to the development of ESP. Importantly, the authors highlight that ESP is not a uniform or universal phenomenon, but rather one that has evolved heterogeneously across diverse settings.

Cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) in the Brazilian context

In Brazil, the CHAT has been widely applied across various fields, especially in education, teacher development, school psychology, and social projects. Based on the foundations laid by Vygotsky and further developed by authors such as Leontiev and Luria, this theory influences pedagogical practices that understand human development as a socially mediated and historically situated process. In the educational field, the theory has guided approaches that value the active role of students and the cultural artifacts that mediate consciousness in school environments as essential elements in the construction of knowledge. Within this perspective, language is conceived as a fundamental cultural tool, and learning is understood as a collaborative and interactive process rooted in students' social and cultural experiences.

In teacher education, CHAT has served as a foundation for programs that emphasize critical praxis, reflection on teaching practices, and professional development through dialogue and collaboration among educators. Brazilian scholars such as Magalhães, Liberali, Fidalgo, among others, contributed significantly to consolidating this perspective, promoting the development of teachers who are aware of their social role and their insertion in contexts marked by inequality and systemic contradictions. This critical vision is also reflected in school psychology, where the theory supports practices that consider the student as a whole, considering their social, familiar, and cultural relationships. As a result, educational interventions are no longer limited to cognitive aspects but include the historical, social, and political dimensions that influence the teaching-learning process.

Moreover, the theory has inspired numerous academic studies at Brazilian universities such as University of São Paulo (USP), Pontifical Catholic University fo São Paulo (PUC-SP), Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), where research groups explore themes related to inclusion, human development, teacher education, and public policies. This theoretical framework is also strongly present in social and community projects, particularly in initiatives focused on popular education, critical literacy, and work with populations in situations of social vulnerability. These actions reaffirm the theory’s commitment to social transformation, understanding that human development emerges from active participation in meaningful social practices.

In this sense, researchers, teachers, coordinators, practitioners, activists in this field in Brazil work with teaching-learning as a socially situated process mediated by cultural tools, as mentioned, but emphasize the dialectical relationship between individual agency and collective activity. It is especially relevant to teacher education in countries like those of the BRICS, where systemic contradictions are abundant and demand pedagogical approaches that are sensitive to local realities. Thus, CHAT, in its multiple expressions, has played a central role in shaping more human, critical, and transformative educational practices in our context.

In the Brazilian educational context, CHAT is perceived as a theoretical and methodological framework that, according to Liberali, Mateus, and Damianovic (2012:7), can be understood as a theory of human nature. This perspective views activity as intrinsic to the human being, given their immersion in social relations (Oliveira, 2012). The theory aims to understand how the human being - including their consciousness - is shaped within the context of social activities, based on the premise that individuals cannot be dissociated from the sociocultural environment in which they are situated (Cenci; Damiani, 2018). In this sense, as Rodrigues (2012:41) states, “social life is essentially practical,” and it is through praxis that individuals produce their means of subsistence - a historical product resulting from human actions within society.

Rodrigues (2012) also highlights that, from the CHAT perspective, there is an integrated relationship between individuals and the world. This means understanding people as historically situated beings, located in a specific time and space, embedded in contexts shaped by economic, social, cultural, political, and historical dimensions. Consequently, human development is a socially and culturally mediated process.

Thus, social and cultural interactions play a central role in individuals’ cognitive development, as both learning and development are “integrated, situated, distributed, and co-produced within contexts, while also being intrinsically interwoven with them” (Stetsenko, 2008:477).

Another key aspect of the theory is its emphasis on the mediation of cultural tools - especially language - in the development of human thought. Learning, in this view, is conceived as a collaborative process in which individuals construct knowledge together through social interaction. In this regard, Magalhães (2012:15) asserts that language plays a mediating and constitutive role in the formation of individual consciousness, emerging as an essential element in critical and collaborative relationships, and contributing to the understanding and transformation of social, cultural, historical, ethical, and political conditions that influence both individual and collective action and thinking.

Learning, therefore, occurs as individuals internalize cultural tools and use them to solve problems in their environments. Human activities, at all stages and levels of organization, are understood as social creations and should be interpreted as outcomes of historical processes (Daniels, 2002).

Furthermore, as Tanzi Neto, Liberali, and Dafermos (2020) point out, Vygotsky’s cultural-historical theory has been reinterpreted by numerous scholars around the world, particularly in response to the complex challenges of contemporary science. These reinterpretations have broadened the possibilities for understanding and fostering human development across various social, cultural, and educational contexts.

Social activity as curricular organizer

In line with CHAT, which understands individuals as active agents, creators, and transformers of knowledge and the world around them, Social Activity is presented as "the motive that drives the teaching-learning activity" (Liberali, 2009:15), enabling subjects to act reflectively and transformatively (Liberali, 2009:10). This activity is conceived as a central curricular organizer, aiming to bridge the gap between school and life, allowing learners to connect what they learn with the demands of real life (Liberali & Santiago, 2018:20). From this perspective, a curriculum based on Social Activity promotes pedagogical practices grounded in CHAT, with a focus on the articulation between theory and practice in the teaching-learning process (Santos, 2015).

Founded on Leontiev’s (1977/1997) concept of coordinated actions carried out by a group to achieve a shared objective, Liberali (2009) argues that the teaching-learning process through Social Activity enables coordinated actions by individuals working toward a specific goal, emphasizing the fulfillment of participants’ needs in the context of “life as it is lived ” (Marx & Engels, 2006:26). In a society marked by multiple demands, diverse representations of reality, and coexisting worldviews, it is essential to develop participatory modes that offer analytical and critical foundations, so that individuals can make conscious decisions about who they are and wish to become, the attitudes they prefer to adopt, and why (Liberali & Santiago, 2018:20). Within this context, Rodrigues (2012) highlights that teaching-learning processes must consider students as social beings with both individual and collective needs and interests, shaped by their socio-historical-cultural context. Therefore, learning environments should simulate real-life situations that foster active participation. In alignment with this view, Vendramini-Zanella and Delboni (2021:251) state that Social Activity consists of subjects who are aware of their needs and are driven by a specific purpose or desired object.

Incorporating Social Activity into English language teaching-learning is not only feasible but also valuable, as such activities reflect real human actions and help develop learners' full potential (Richter, 2015:62). Participants are encouraged to effect change within their contexts and broader society, with this transformative capacity acting as a driving force that inspires them to envision and pursue improved living conditions and greater civic engagement. Consequently, according to Vieira and Liberali (2021), language teaching grounded in Social Activity seeks to recognize individuals’ everyday actions and aims to empower them to master the discursive genres relevant to effective participation in those activities. In selecting the Social Activities to be addressed in the classroom, the idea is that additional language learning should serve to enrich personal and cultural development, since “activities related to cultural participation involve language issues” (Liberali, 2009:16). This approach is also supported by the intrinsic connection between Social Activities and everyday life, as they emphasize collective action undertaken to achieve a shared motive or goal, thereby meeting the concrete needs of the individuals involved (Liberali, 2009:11).

In order to elucidate the components of an activity-namely, “agents (subjects) who recognize their needs and are motivated by a purpose (object), which is mediated by artifacts (instruments, tools) through a relationship among individuals (community), constituted by rules and the division of labor” (Liberali, 2009:19) - and to relate them to the activity examined in this study, Table 1 below presents the components of activity as proposed by Liberali (2009), drawing on Engeström’s (1999) representation.

Table 1. Components of activity

|

Component |

Description |

|

Subjects |

Those who act in relation to the motive and carry out the activity |

|

Community |

Those who share the object of the activity through the division of labor and rules |

|

Division of Labor |

Intermediate actions performed through individual participation in the activity, which alone do not fully satisfy participants’ needs. These include the tasks and functions assigned to each subject involved in the activity |

|

Object |

That will fulfill the need—the desired object. It is dynamic in nature, transforming as the activity develops. It involves the articulation between what is idealized, dreamed of, or desired, which evolves into the final object or product |

|

Rule |

The explicit or implicit norms established within the community |

|

Artifacts / Instruments / Tools |

The means by which nature is modified to achieve the idealized object. These tools can be controlled by their user and reflect the subject's decisions. They are used either to achieve a predefined goal (instrument for a result) or can be formed throughout the activity itself (instrument and result) (Newman & Holzman, 2002) |

Source: Liberali, 2009:12

Rodrigues (2012:54) argues that a curriculum organization grounded in Social Activity seeks to support teachers in the comprehensive process of instructional planning, which includes the design, sequencing, implementation, and reflection on tasks to be carried out by students, as well as on the teacher's own classroom practices. In addition, such a framework entails a critical examination of the curricular content to be addressed, considering the lived realities of students and beginning from their needs to identify the most relevant social activities to be incorporated into the pedagogical approach (Liberali & Santiago, 2018:26–27).

Within the context of ESP, this means expanding the scope of language teaching to include discussions on power, identity, and inequality - topics often shaped by colonial and neoliberal ideologies. Rather than reproducing dominant narratives, educators are encouraged to foster a dialogic classroom environment where learners critically engage with the sociohistorical dimensions of language and power.

Drawing from decolonial theorists such as Maldonado-Torres (2008), Mignolo (2017), Quijano (1999), and Walsh (2012), this pedagogical stance emphasizes the need to unveil, and question taken-for-granted discourses rooted in coloniality. Quijano (1999), for instance, conceptualizes coloniality as a persistent structure of power that outlives colonialism, shaping knowledge, identities, and social hierarchies. Mignolo (2017) extends this by calling for epistemic disobedience - that is, a delinking from Eurocentric frames of reference to re-center subaltern knowledges and practices. Maldonado-Torres (2008) further deepens the critique by exposing the logic of dehumanization embedded in coloniality, arguing for a decolonial turn that reclaims human dignity through ethical and political action.

In educational settings, as Walsh (2012) suggests, this entails not only including diverse perspectives but actively resisting epistemic violence and enabling students to construct alternative, pluriversal meanings. Language education, from this vantage point, becomes a transformative space for disrupting hegemonic narratives and cultivating critical, inclusive subjectivities capable of imagining and enacting more just social worlds.

This critical orientation is particularly pertinent within the BRICS framework, where the negotiation of national identity, linguistic diversity, and global participation remains a central concern. By embedding discussions that confront colonial legacies and racist structures-framed within broader liberal discourses-language education can better respond to the socio-cultural differences of BRICS participants. Without necessarily engaging in politically sensitive critiques, especially in multilateral contexts, such a focus allows for an ethically grounded and contextually sensitive approach to teacher education. Ultimately, it strengthens the emancipatory potential of language pedagogy while respecting the geopolitical complexities that define BRICS cooperation.

In this perspective, the teaching-learning framework proposed by LinFE serves as a curricular orientation tool. It aims to map out the structure and operational dynamics of a Social Activity, to establish meaningful interactions among the constituent elements of the activity system, thereby promoting a more situated and contextually responsive educational experience.

Materials and methods

This research was conducted at a public Higher Technological Education Institution in the State of São Paulo, called the Faculty of Technology of Praia Grande, located in the city of Praia Grande, in the Metropolitan Region of Baixada Santista, São Paulo, Brazil. Higher Technological Education in Brazil is characterized by undergraduate programs known as Higher Education Technology Courses, which typically last around two years and are aimed at developing technologists - professionals qualified in specific fields.

A Higher Education Technology Course stands out as a form of Higher Education that, by combining theoretical and practical knowledge, offers fast, practical, and market-oriented appropriation, setting it apart from other modalities such as bachelor's and teaching degrees.

With a strong emphasis on the immediate appropriation of acquired skills, Higher Technological Education becomes appealing to students seeking to enter the job market with specific competencies: “Its specificity lies in the fact that it provides specialized training in scientific and technological fields, granting graduates the skills to work in specific professional areas” (MEC, 2024).

This research is methodologically grounded in the Critical Collaborative Research framework, hereafter referred to as PCCol, as conceived by Magalhães (2006). It aligns with the critical research paradigm in which the teacher-researcher investigates both the actions of the participants - that is, the students - and their own pedagogical action.

PCCol, whose critical-interventionist foundation is rooted in collaboration as a methodological principle, is: “partially derived from action research, although the concept of collaboration in the research process is, for us, central” (Magalhães, 2007:151–152).

Accordingly, Magalhães (2006:156) describes PCCol as an interventionist research method that:

- involves all participants in the mediation, collection, analysis, and understanding of concepts, in value judgments, and in decision-making processes regarding what to do and how to act;

- provides tools for all participants to engage in observing, questioning contradictions, and appropriating and using new mediational tools to analyze and reorganize their own practices;

- enables the analysis and understanding of different discursive perspectives, considering multiple voices, viewpoints, and approaches.

When considering collaboration, it is important to understand that within PCCol it is intrinsically tied to critical collaboration, which has been: constructed over the years to challenge a Cartesian view of collaboration/cooperation, incorporating categories such as contradiction, conflict, intervention, mediation, negotiation, and resistance (Magalhães & Fidalgo, 2019:11), that is, critical collaboration because it challenges lexical and structural choices, and is fundamentally grounded in discourse.

Table 2. Description of meeting

|

Schedule |

Activities |

|

Social activity |

1. Opening of the session with the song “Feelin' Groovy” by Simon & Garfunkel |

|

2. Discussion of section “1.3 Social Activities” from the text “Foreign Language Teaching” by Liberali (2009) |

|

|

3. Collaborative co-construction of a mural with ideas and keywords related to Social Activity |

|

|

4. Discussion of the components of Social Activity |

|

|

5. Selection of intervention contexts for Social Activity |

|

|

6. Initial development of the Social Activity for each selected intervention context |

|

|

7. Completion of the session evaluation questionnaire |

Source: Diegues 2025:112

The session began with the song "Feelin' Groovy" by Simon & Garfunkel, selected by one of the teacher-participants. She shared the personal significance of the song, which led the group into a discussion on the importance of slowing down and reflecting on life in an increasingly fast-paced world. The teacher-participants shared their experiences regarding the pursuit of balance between work, study, and self-care, touching on activities such as meditation, reading, and physical exercise.

Subsequently, the concept of Social Activity was discussed drawn from Liberali's (2009) text. The reading emphasizes the importance of reflecting on one’s life and transforming it toward more meaningful participation in society, highlighting the role of the CHAT in teaching-learning. During this session, key points were raised concerning the integration of students' real-life experiences into the teaching-learning process, thus promoting agency and developmental potential.

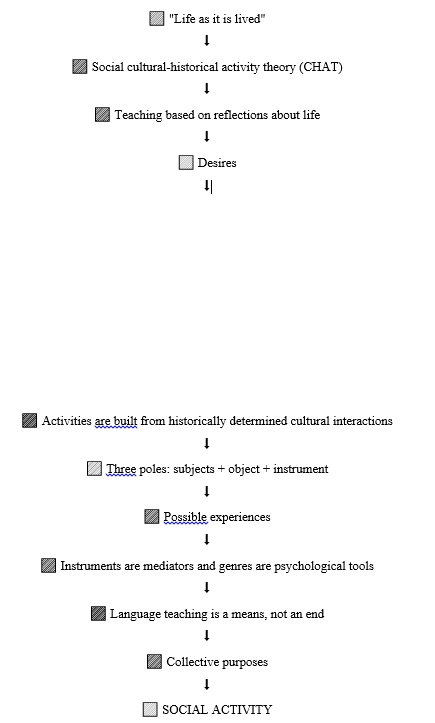

Following the theoretical discussion, participants collaboratively constructed a mind map (see Figure 1) on Social Activity, highlighting key components such as subjects, object, tools, and division of labor.

Fig. 1. Collaborative Mural on Social Activity

Source: Diegues, 2025:114

The practical task for this meeting involved selecting three intervention contexts related to Social Activity that consider the students’ socio-historical-cultural backgrounds. The teacher-participants selected teaching-related contexts, namely: (1) presenting a scientific paper, (2) writing an email, and (3) producing a video résumé. The session concluded with a discussion on the preparation of the components of Social Activity for each of the selected intervention contexts.

In Table 3 below, we present Excerpt 1, followed by its data analysis and discussion.

Table 3. Excerpt 1

|

Researcher: [...] we can start with you - I’d like you to briefly share what you understood from the text, what social activity means to you, and the key points you noted. Teacher I: Well, I try to bring it into our reality, and it's something I believe in. Experience sustains the construction of lesson content and engages students -or draws them in - so they can have a reference point, something they can identify with, making it meaningful. I loved the phrase “life as it is lived,” because it's from there that we can develop our strategies. There’s no use in teaching something disconnected from the reality we live in - or that our students live in - because it will lack meaning. It’s crucial that it has meaning for them. One important thing I noted - I even sketched a mind map - is that we must start from the subject. From the subject, we move to the object, because there must be a desire, a motivation, to develop the activities. These activities need to be instrumentalized, there has to be a network, rules, and division of labor. There must be collective participation, and it must have meaning. Teacher II: Can I say something in my defense? I just remembered that this was part of a class I took - I think it was a course on teaching methodologies - and we had to design an activity based on social activities. I’ll try to find it on my old computer. I remember I created something like “going to the movies,” and it included The Big Bang Theory - it turned out pretty well. Researcher: Thank you, would you like to add something? Teacher III: [...] A few points really caught my attention. I highlighted what [Teacher I] mentioned about reflecting on “life as it is lived,”. So, bringing the reality of that community into the classroom, and from that reality, developing the activities. Correct me if I’m wrong, because honestly I’ve never read much about social activities - maybe I misunderstood something - but my understanding is that we bring the community’s reality and always work toward a collective goal. So, foreign language activities aren’t defined solely by a linguistic aim - like acquiring a grammatical structure. They position themselves as tools. That’s how I interpreted “tools”: the activity allows for collective thinking. These activities are constituted through interactions - this is something the author emphasizes in the text - interactions that are part of culturally and historically situated contexts. All of these elements permeate our teaching practice and also the learning process. I found it interesting that she mentions there is no such thing as an isolated activity. Rather, there is a network, a system of interconnected activities. [...] Researcher: That’s a crucial point - thank you, everyone. Regarding social activity, it is grounded in CHAT, which sees subjects as always interacting with one another. In these interactions, within the collective construction of an activity, mediated by an object or a shared goal, and through the use of tools, they are situated in culturally and historically dependent contexts. Something you said, [Teacher III], is particularly insightful - that it’s not only about language as an end in itself. This is something we’ve been reflecting on a lot. We’ve been questioning and discussing other theoretical perspectives, and this one highlights that teaching English isn’t just about teaching the language per se. We must approach language teaching through many other lenses. Social activity opens up multiple possibilities - ways of being, acting, living, and feeling the world, we are a part of, in all its cultural and historical depth. |

Source: Diegues, 2025:113

The excerpt above (Table 3) and the mind map (Figure 1) highlights the collective construction of meaning in education, focusing on the integration of theory and practice through the concept of Social Activity (Engeström, 1999; Liberali, 2009). Researcher’s initial intention was to provoke reflection and dialogue among participants regarding the relationship between what is learned and what life demands (Liberali & Santiago, 2018). Teacher 1’s remarks emphasize the necessity of connecting educational content to students’ lived experiences, promoting meaningful learning based on real-life relevance and personal identification with the topics discussed. This perspective aligns with a critical approach that values the design of activities grounded in the subject, their interactions, and collective participation (Magalhães, 2007, 2009, 2012). In this regard, we underscore the social role of the classroom, which goes beyond the mere transmission of content and becomes a space for the formation of critical and engaged citizens. Within this context, teaching contributes to participants’ understanding of the interconnections between learning and its application in social, professional, and cultural contexts.

Furthermore, Teacher III adds to the discussion by stating that language teaching transcends the acquisition of linguistic structures, functioning also as a tool for collective action embedded in specific historical and cultural contexts (Liberali, 2009). In this sense, the type of knowledge and interactions fostered through teaching contribute to the development of learners’ identities, enabling them to perceive themselves as historical and social agents capable of transforming their realities through language. The view of human beings and society promoted through the pedagogical practice illustrated in the excerpt is founded on principles of collectivity, autonomy, and critical reflection (Magalhães, 2007, 2009, 2012). The human being is understood as an active subject who learns and constructs knowledge through interaction with others and the world, in a continuous movement of transformation.

Researcher reinforces that social activities, grounded in CHAT, provide opportunities for education to become multidimensional and meaningful, breaking away from the traditional and reductionist views often found in foreign language teaching. Thus, the excerpt, rooted in the participants' discussion based on Liberali’s (2009) text, highlights the transformative potential of teaching through multiple forms of interaction, reflection, and action.

However, activities such as producing video résumés or writing professional emails only become pedagogically powerful when students recognize their relevance and feel seen through them. Integrating students’ perspectives-through feedback, dialogic engagement, and participatory curriculum development-not only validates their agency but also fulfills the transformative discussion of language education rooted in CHAT.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that language teacher education in Brazil, when grounded in Social activity and cultural-historical principles, holds significant potential for fostering culturally relevant and socially transformative pedagogical practices, not only locally but across BRICS contexts. Through the PCCol process, we observed how reflective, dialogic engagement allowed teacher-participants to reinterpret their professional roles, reconnect with students' lived realities, and develop pedagogical strategies rooted in ethical, political, and transformative commitments.

By centering the concept of Social Activity as both a curricular organizer and a reflective lens, educators moved beyond utilitarian or technical approaches to ESP. Instead, they embraced language teaching as a sociocultural, ideological, and identity-shaping practice. The collaborative design of activities such as preparing scientific presentations, composing professional emails, and creating video résumés illustrates the viability of integrating students' real-life needs into language learning, while also resisting the neoliberal logic often imposed on education systems in BRICS countries.

The findings reinforce the relevance of CHAT in shaping a teacher education paradigm that is responsive to systemic contradictions, historically situated, and ethically grounded. This perspective enables teachers to become agents of change within institutions that are often pressured to align with market-driven imperatives. Within the broader BRICS context-marked by diverse cultural heritages, postcolonial dynamics, and geopolitical tensions-this Brazilian experience offers a pathway toward collaborative resistance, decolonial epistemologies, and pluriversal approaches to language education.

Ultimately, this study affirms that when teacher education prioritizes dialogue, collective activity, and transformative social action, it not only enriches the professional development of educators, but also fosters pedagogical practices that are responsive to diverse social realities. By centering collaboration and critical engagement, such approaches actively contribute to the construction of more inclusive and equitable educational landscapes-both locally, within specific communities and institutions, and globally, as part of broader movements toward social justice and educational democratization.

1 In Portuguese