Introduction

Within cultural-historical psychology, one of the most persistent and significant lines of inquiry has been the study of how scientific concepts develop through school-based education (Chapaev, 2015; Gennen, 2024; Romashchuk, 2024; Waermö, Broman, 2024; and others). A substantial breakthrough in this area became possible due to the work of the distinguished dialectical philosopher E. V. Ilyenkov (Ilyenkov, 1974; Ilyenkov 2017) and the founders of the theory of learning activity, D. B. Elkonin and V. V. Davydov (Davydov, 1996; Davydov, 1999; Elkonin, 1989). Their analyses revealed a fundamental distinction between the acquisition of empirical generalizations and that of theoretical concepts. Crucially, they showed that it is the appropriation of theoretical concepts that enables the development of reflective thinking and consciousness. As Ilyenkov insisted, “the specificity of ‘generalization’ in a concept lies not in identifying something abstractly common, but in identifying the universal — the law that makes a thing precisely the thing it is, and not another, in all its definiteness, particularity, and singularity” (Ilyenkov, 2017, p. 213).

Although these ideas were articulated more than fifty years ago, the content of basic school education has changed only marginally. Part of the reason is structural: a genuine transformation of curriculum content demands a deep logical-subject matter analysis capable of reconstructing the development of a concept from its “initial cell,” its initial abstraction, to its fully concrete articulation — that is, following the logic of ascent from the abstract to the concrete.

To date, examples of constructing curriculum content according to this logic remain scarce. Exemplary cases exist for primary school, notably the conceptual lines of number and phoneme (Davydov, 1998, and others). Attempts have also been made to design learning activity—based courses for lower- and upper-secondary students, for university education, and for adult learning (Rubtsov, Elkonin, Zuckerman, Ulanovskaya, 2024; Elkonin, Vorontsov, Chudinova, 2004; Engeström, 2020). Yet these initiatives tend to focus primarily on methodological dimensions of instruction rather than on the logical reconstruction of subject matter.

The purpose of this article is to demonstrate, through a concrete example, what a system of learning tasks looks like when organized as an ascent from the abstract to the concrete — the educational trajectory students undertake and how their thinking and consciousness develop along the way.

The central hypothesis is that a concept jointly constructed by a class in accordance with the logic of ascent can become not only a tool for thinking within the specific school subject but also a means through which students can become aware of, interrogate, and transform their everyday experience.

Materials and methods

The material for this study was drawn from biology instruction for 11—13-year-old students (the topic “The organism: its structure and functioning”). To develop new instructional content, we conducted a logical-subject matter analysis and a Logical-psychological analysis of the concept of an organism. This was followed by a formative experiment: instruction based on the course New Biology, module “Animals,” which extended over approximately one school year (60—70 instructional hours).

To test the research hypothesis, we used the diagnostic method “Sparrow and Birch”. Using this instrument, we assessed 227 students in Grades 6 and 7 in the experimental classes (104 girls and 123 boys) and 199 students in the control classes (86 girls and 113 boys). The control classes were drawn from the same school and two other schools with comparable location and social composition of the student body. Students in the control classes were taught using the most widely implemented biology curriculum currently used in Russian schools1.

Students were asked to write five statements (“what I already know”) and five questions (“what I want to find out”) about two familiar organisms — the sparrow and the birch tree — in order to reveal their understanding of how the organisms are structured and how they function. Each statement was evaluated by three independent experts on a scale of content accuracy and scientific quality (0 to 5 points). Comparisons between the experimental and control classes were carried out using the Mann—Whitney U test.

Results

Results of the logical-subject matter analysis: identifying the subject content of instruction and the conceptual logic

For the developers of a learning course, the first task is to identify and understand what Ilyenkov calls the law that determines a given “thing” — in this case, the logical path by which thought arrives at a definition of the organism as a unity of structures and functions. This work, carried out by the course designers, is referred to as logical-subject matter analysis (Davydov, 1996). Such analysis reveals — and, when required for instructional purposes, reconstructs — the logic of the concept’s development, a logic often concealed within the long historical trajectory of scientific thought.

Ilyenkov writes: “Human thinking proves capable of uncovering the objective ‘beginning’ of a process only through analysing its highest results” (Ilyenkov, 2017, p. 241). Accordingly, the initial work of the developers consisted in analysing contemporary scientific achievements together with the historical development of biological knowledge, in order to understand the structure and functioning of highly developed organisms (for example, humans, higher animals, and plants). Examining the structure and functioning of such organisms made it necessary to identify an “initial cell,” whose developmental potential could give rise to the past and presently existing biological diversity.

In our case, the logical-subject matter analysis of the scientific conception of the organism as a unity of structures and functions required identifying and reconstructing this initial cell — the understanding of the body’s boundary as a relation between the internal and external environment2.

The boundary is a structural element that renders a living being discrete, separating its internal content from the surrounding environment. The concept of the body’s boundary functions as the initial cell because it contains within itself the potential to develop into the full concept of the organism. The boundary is internally contradictory: it simultaneously separates and connects the inner and outer environment. This abstraction can therefore serve as the foundation for a developing instructional model — the future concept of the organism3. The contradiction inherent in the boundary is resolved across the diversity of structural solutions that nature has produced in living beings. The logic of the emergence of this diversity can become the basis for a system of learning tasks within the course.

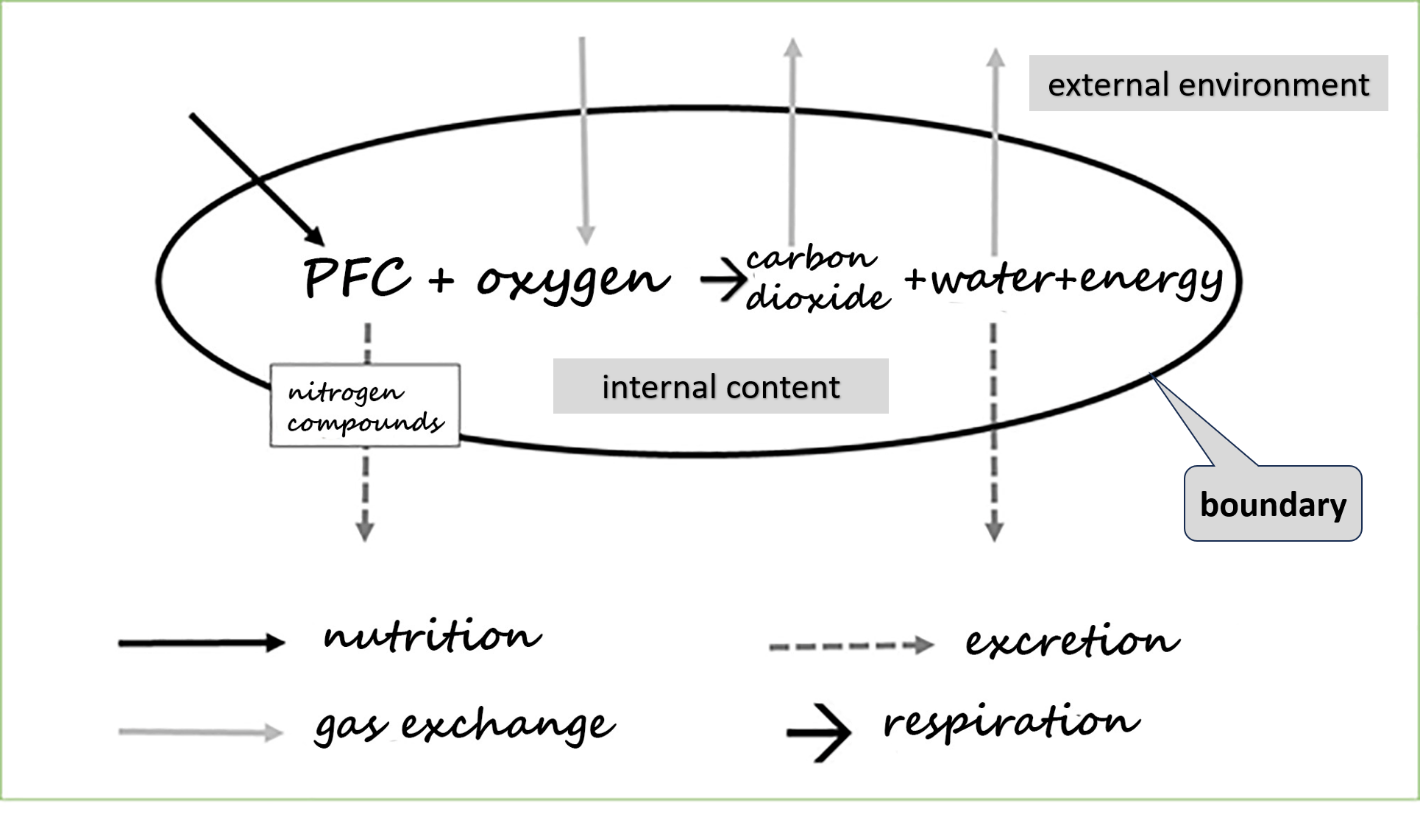

Thus, the content of the course was presented as a systemic body of theoretical knowledge in which the initial abstraction becomes progressively concrete in more specific cases logically derived from it (the ascent from the abstract to the concrete). The initial model form was a diagram capturing the unity of the principal vegetative processes of the organism (Figure 1) (Chudinova, Zaytseva, 2022).

This diagram shows the logical connection among the processes of respiration, nutrition, gas exchange, and excretion, as well as the “location” where these processes occur. Respiration4 — the acquisition of energy — takes place inside the body, whereas all other processes occur at the boundary between the internal and external environment. Through these processes, substances necessary for respiration enter the body, while unnecessary or harmful substances are removed. Thus, the initial relation between the internal and external environment is represented, at the starting point, as a closed line designated by the term “boundary.”

Results of the logical-psychological analysis: identifying deficits in students’ initial knowledge and skills, and constructing the sequence of learning tasks

Logical-psychological analysis makes it possible to embed the subject-matter logic that has been identified into a system of learning tasks appropriate for a given age group and level of schooling. As V. V. Davydov observed, “it is often very difficult for the psychologist and the didactician to determine the concrete actions that open up the content of concepts” (Davydov, 2006, p. 42). This difficulty is real: it is necessary not only to assess the children’s existing concepts and representations but also to understand their developmental potential — the zone of proximal development of their biological thinking. Students beginning the study of biology hold certain initial ideas about living beings, but they lack many of the concepts in chemistry and physics that are essential for biological understanding.

The outcome of the Logical-psychological analysis was to determine how students could arrive at the first initial abstraction, and in what form and through which actions this abstraction could emerge in instruction. This required constructing a methodology through which students could analyse phenomena observable in simple experiments and transform their everyday representations in such a way that the first learning task could be set.

In our case, it became clear that students could not be brought to the initial abstraction of the boundary without developing their initial ideas about respiration (Chudinova, Zaytseva, 2022), as well as their understanding of the composition of the internal and external environment. This implied the need for several months of preliminary work with the students (Chudinova, 2019). The joint investigative work of the class had to focus on changes in air during respiration, and on processes of nutrition, gas exchange, and excretion. Observations and experiments involving the students’ own bodies were to serve as the primary material for analysis. When such observations were impossible for physical or ethical reasons, descriptions of observations of animal organisms could be used. Thus, the “reduction” to the initial relation also had to occur through the analysis of developed forms — complexly organized organisms.

The Logical-psychological analysis ultimately clarified which specific steps of concretization would be appropriate in this instructional sequence. Some interesting logical—subject-matter insights had to be set aside because the expected learning outcomes needed to be aligned with the requirements of the educational standard. The sequence of learning tasks was determined by the fact that the results of solving earlier tasks were necessary for solving those that followed.

Description of the formative experiment: movement through content as the ascent from the abstract to the concrete

As noted above, the body’s boundary initially appeared to students in a maximally abstract form — as a line in the diagram, labelled by the teacher as “the boundary of a living being’s body.” Students understood only the most general fact: that this line limits the body and divides space into what is “inside” and what is “outside.” In this way, the boundary between the internal and external environment first emerged as a shared, general representation for all students in the class. The term boundary entered the discussion as the class reasoned about where the processes already identified in earlier investigations — nutrition, gas exchange, respiration, and excretion — take place.

The first substantive step in understanding the boundary itself occurred as students discovered its central contradiction and attempted to resolve it. The body’s boundary must simultaneously maintain and preserve the internal environment — distinct in both properties and composition from the external environment — and, at the same time, allow certain substances to pass through it. It must, for instance, let in air, water, and organic substances required for cellular respiration. Thus, the boundary must perform two tasks that are opposite in meaning. This contradiction is never made explicit at the moment when students collaboratively construct the initial diagram (Fig. 1).

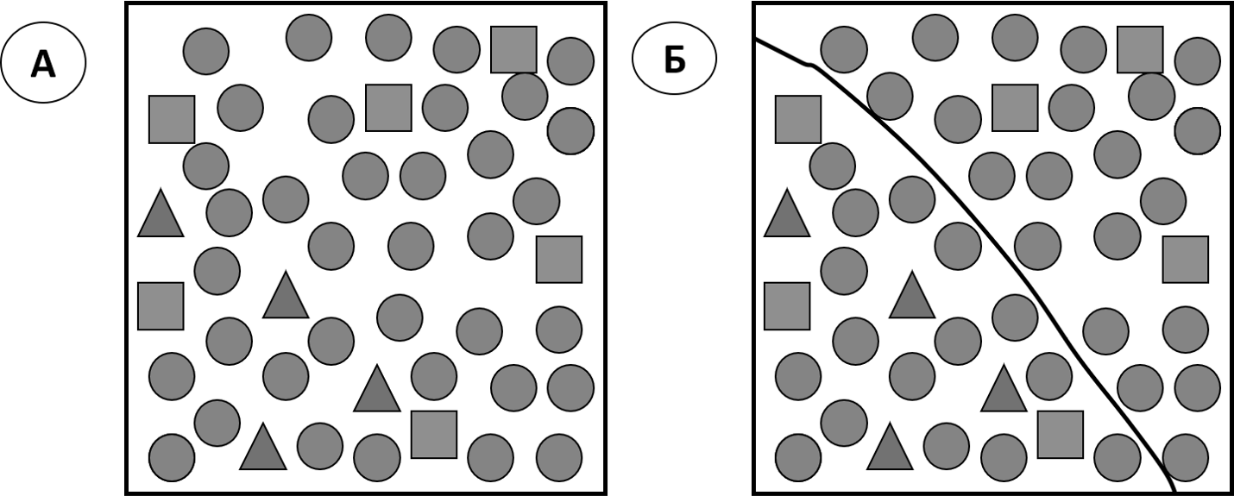

When asked to draw a “molecular scheme” of the edge of a jellyfish’s body in seawater, based on the given diagrams showing the composition of the internal and external environments, students proposed two opposing versions (Fig. 2).

To ensure that students experienced this contradiction in a vivid and grounded way, the teacher intentionally amplified it. The class discussed which drawing corresponded more closely to reality. Because a molecular picture was required, no “non-molecular” lines were allowed — after all, both the jellyfish and seawater consist solely of molecules. This immediately ruled out version “B.”

To evaluate version “A,” the teacher invited several students to the board to reproduce version “A” using colored circular magnets. Unlike the static circles in the drawing, the magnets could be moved, and many students immediately thought to demonstrate diffusion6.

“The jellyfish is dissolving!!!” the students exclaimed as they saw what happened. It turned out that the second version was also unsuccessful. The teacher further sharpened the contradiction, and the students began to feel the real problem of the boundary — they no longer understood what it was or how it worked. Some even wondered whether it existed at all. As they became aware of the contradiction, students articulated it verbally, in ways such as: “But this is paradoxical! The boundary lets some molecules through but not others!” or “Maybe some parts of the boundary let things through, and some parts don’t…”. They recorded the contradiction in writing, after which they were assigned a series of tasks meant to help them approach a solution. These included experiments with boundaries made of polyethylene, cellophane, and gauze; a home experiment with a representative of the living world — a carrot; and a virtual experiment in the practical module Types of Boundaries7.

Through analysis of these tasks, the initial abstraction of the body’s boundary developed and became more concrete in the concept of a selectively permeable boundary. Later, when students studied a “simple” living organism — the amoeba — they encountered the cell membrane as the concrete embodiment of such a “most elementary” boundary (as termed in the text)8.

The next step in the development of the concept involved overcoming the fixation on the boundary’s structural integrity and immobility. This began with examining amoeba movement, and then with analysing its nutrition. In formulating hypotheses about how an amoeba feeds, students discovered that the size of the amoeba’s food creates a problem for the passage of necessary substances through the boundary of its body. The unicellular organisms eaten by the amoeba are too large to pass through the membrane into the internal environment. This prompted an examination of the stages of feeding (e.g., preliminary fragmentation of food) and shifted the notion of the body’s boundary — it was now understood as sufficiently mobile and active, capable of changing shape to capture food.

As the students continued studying unicellular organisms, the question arose: what prevents them from being large — for example, the size of a human? They conducted an investigation of the ratio between the surface area of the body’s boundary and the volume of that body. They identified one of the factors preventing unicellular organisms from surpassing a certain size threshold: as body volume increases (with shape held constant), the surface area available per unit of volume decreases. To overcome this size threshold, students “invented” a multicellular organism. The fundamental contradiction of the boundary reappeared, but on a new level. Students realized that the cells inside a multicellular body would require oxygen and organic substances from the external environment, and would also need to dispose of unnecessary or harmful substances. However, the boundary of the organism was no longer the membrane of a single cell, but layers of cells in contact with the external environment.

How, then, should the needs of the internal cells be met? Working on this new task led students to invent constructions involving cell specialization. Typically, at least one student group proposed a design with mobile cells — “carrier cells” — moving between the boundary and the internal cells. At this point, new potential pathways of conceptual movement emerged: towards the study of transport systems and the study of tissue types in living organisms.

The teacher then introduced a new phenomenon for investigation: a jellyfish washed ashore during a storm dies. Many students had seen this themselves. But why does it happen? Various explanations were discussed. The version “the jellyfish dissolves” was dismissed upon closer examination. Students concluded that the jellyfish dries out. But this contradicted the fact that other multicellular organisms — humans, for example — can remain in air without drying.

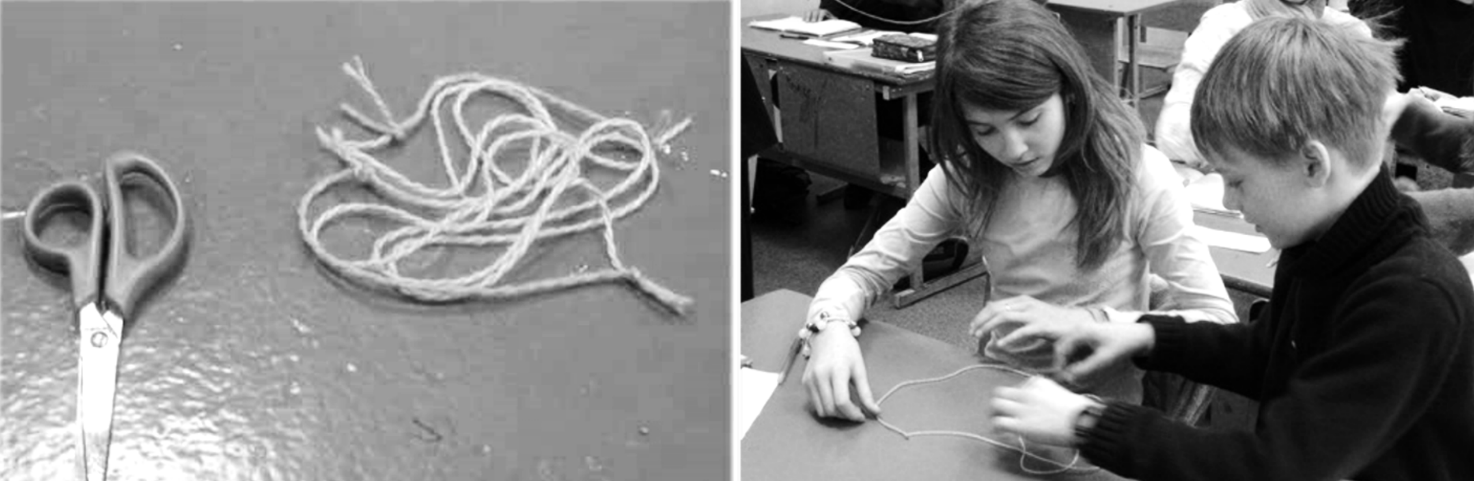

The thought occurred to many: “Maybe some parts of the boundary let things through, and some do not…” Returning to the model “Body size / surface area” allowed students to understand that the exchange-active part of the body’s boundary must be much more extensive than its protective part. The teacher suggested modelling this using strings of different thicknesses.

By tying together two strings — one long and thin, the other short and thick — students obtained a movable model of the body’s boundary consisting of two parts: an exchange-active part and a protective part9.

The task was to strengthen the protection of the internal environment without losing the ability to carry out exchange with the external environment (Fig. 3). All possible solutions involved “folding” the exchange-active part of the boundary and hiding it — fully or partially — under the protective part. The resulting variants later turned out to correspond to different types of gas exchange in multicellular animals. Over several lessons, students studied concrete material on these types of gas exchange, including in humans, by reading scientific texts.

Next, the structural variants they had constructed were tested for their suitability for carrying out the function of nutrition. It became clear that, for various reasons, these designs were not particularly effective for the new task. Analysing their shortcomings led to the discovery of the through (complete) digestive system. All structural “inventions” supported the emergence of a new way of seeing— a new approach to considering the structure of multicellular animals, to “reading” diagrams of their structure by distinguishing between internal and external environments and between exchange-active and protective parts of the body’s boundary.

The concept of the boundary became increasingly concrete through analysis of the diverse structures of multicellular animals. Students could now see that as the boundary transforms, so too do the structures and forms of living beings, altering the spatial relationship between the internal and external. An “external environment” begins to appear inside the body — for example, air in the lungs or the contents of the digestive tract.

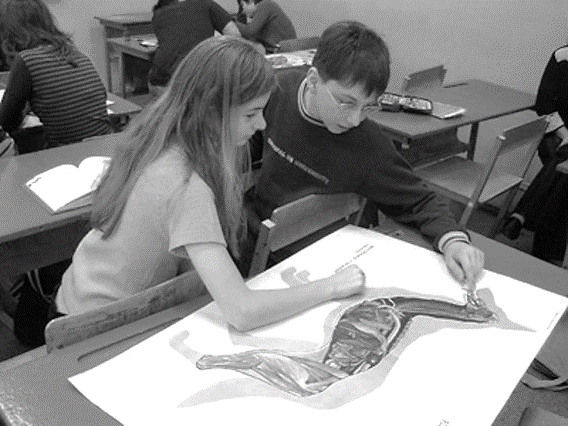

Fig. 4. Working in pairs, students analyse an image of a dog's internal organs, trying to figure out on their own where (at which boundaries) gas exchange, absorption of organic substances, and excretion occur. Understanding the general principles of the structure of multicellular animals allows them to do this

The more concretely students understood the boundary, and the more deeply they explored the possible details of its structure, the broader and more comprehensible the diversity of possible organismal structures and functions became to them. The concept gradually turned into a set of “lenses” through which they began to view the material presented for study: descriptive texts about living beings, schematic drawings of their structure, and video fragments of their lives (Fig. 4).

As students continued into Grade 7 with the study of the human excretory system, they discovered the phenomenon of active transport — that is, the exchange-related “work” of the boundary carried out with an expenditure of energy.

By the end of Grade 6, having completed their study of the major vegetative functions of animals and the structural features supporting these functions, the students had, in effect, constructed the concept of the organism. Only at this point did the teacher introduce the term organism. Prior to this, the term had not been used; and if a student mentioned it, the teacher asked: “Do you know what an organism is? Not exactly? Then let’s not use this word yet.”

Showing the students’ jointly constructed diagram, which represented the connections among major vegetative functions in animals, the teacher would say: “This is what we call an organism. Try to formulate what it is.” Students read their definitions aloud, and by selecting the most precise formulations, they composed a shared class definition, typically something along the lines of: “An organism is a set of interconnected structures (organs) that perform different functions.”

After this, the class moved on to the study of plants. The teacher displayed an image of a spruce — a tree familiar to all as a New Year symbol — and said: “You can look at a spruce with different eyes. A gardener will be pleased by how lush, green, and fast-growing it is. An artist will see how it fits into the landscape, how it is lit… Try to look at the spruce as an organism. Write down what you can claim about it and what questions you would like answered.” This marked the beginning of the next major stage in the concretization of the concept of the boundary and of other concepts whose development had begun in the previous stage.

Results of the diagnostic assessment of concept development in traditional instruction and in the New Biology course

We can speak of genuine scientific understanding only when the concepts students have mastered exist not merely as verbal formulations reproduced when prompted, but when these concepts transform the way students view the objects around them — including those that were never explicitly discussed in class.

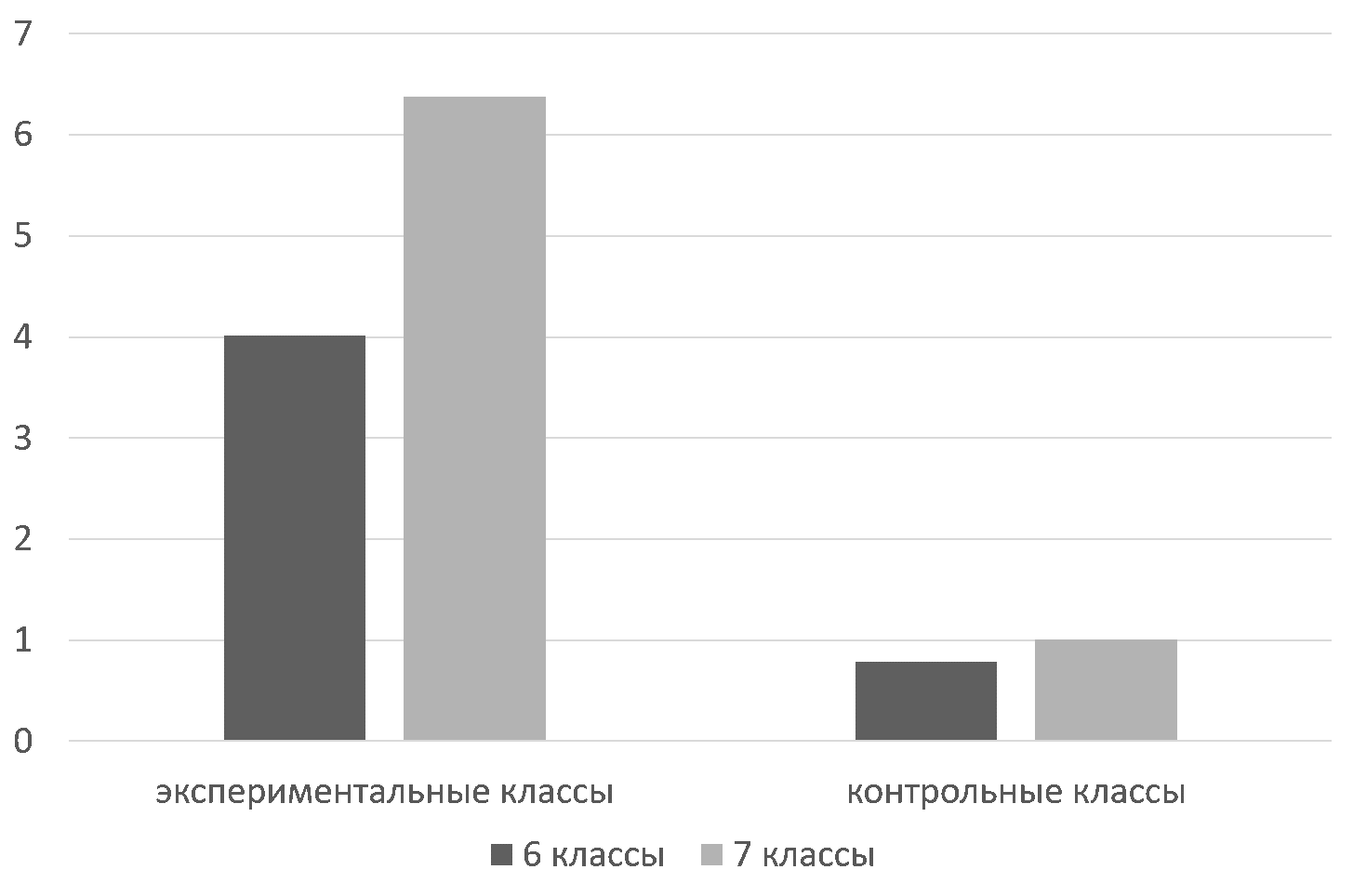

The study involved Moscow schoolchildren who had studied for one or two years in the traditional program (199 students in total) and students who had studied for one or two years in the New Biology course (227 students in total). Sixth- and seventh-grade students wrote what they knew and what they wanted to know about the structure and functioning of the birch and the sparrow — two organisms familiar to everyone since childhood. Each statement was evaluated by three independent experts according to agreed-upon criteria, on a scale from 0 to 5 points, depending on its level of substance and proximity to scientific understanding. The substance and scientific quality of the questions and statements produced by students taught through the developmental approach described above were substantially higher (Fig. 5). Comparison between the experimental and control classes using the Mann—Whitney U test revealed significant differences in both Grade 6 and Grade 7, as well as in the combined analysis of all data (p < ,001).

Evidence of reliance on scientific understanding of the organism appeared in the way students applied general principles to familiar but school-unexamined organisms — the bird and the tree. For example: “Respiration in the sparrow occurs in every cell,” “The sparrow contains inorganic substances,” “The birch is a multicellular organism.” Indeed, it is precisely these “conceptual lenses” that sharpen students’ vision of the object and allow them to detect something new or puzzling in it: “What type of boundary does the sparrow have?”, “Are contractile vacuoles possible in the birch?”, “Where does the birch obtain water and mineral salts?”, “Is the sparrow’s transport system closed or open?”

Fig. 5. The diagram shows the average number of statements rated by experts (≥ 3 points out of 5) in the experimental and control classes (1 and 2 years of learning biology). It is clear that in the experimental group, by the end of the 6th grade, students on average write down about four meaningful statements, while for seventh-graders this number increases to six or more (out of 10 possible). In the control group, the indicators remain extremely low: less than one statement in the 6th grade and about one in the 7th grade

The overwhelming majority of questions and statements formulated by students taught in the traditional way were everyday in character. They remained tied to personal impressions, direct observations, and familiar representations, and often had no relation at all to what an organism is. For example: “My mother loves birches,” “Why is birch bark white?”, “Birch pollen causes allergies,” “A sparrow has two legs and two wings.”

Thus, the differences between the groups are qualitative in nature: students in the developmental-instruction setting show a clear increase in the number of substantive statements as their learning progresses, whereas traditional instruction does not lead to any substantial progress.

Discussion

The importance of transforming the content of traditional education and designing instructional courses on the basis of the principle of ascent from the abstract to the concrete is emphasized in contemporary research (Chapaev, 2022; Engeström, 2020; Gennen, 2024). Yet the core difficulty lies in moving from an understanding of this general philosophical principle to a concrete methodology of instruction — a transition that necessarily relies on both logical—subject-matter and Logical-psychological analysis (Davydov, 1998). The instructional trajectory described above provides an example of such a transition.

Unfolding the conceptual logic through a system of learning tasks reveals the transformation of the initial abstraction of the body’s boundary into the concept of the organism — one of the central concepts in the school biology curriculum. This example clearly demonstrates the evolution of models and the role of the class’s collective cognitive movement in their construction. The path of abstraction, the forms of modelling, and the logic of concretization are determined by the very object of thought, as other researchers also note (Waermö, Broman, 2024). Along this path, constructive critique of prior representations and concepts — their sublation — is essential (Romashchuk, 2023). Emphasizing the role of such constructive critique, A. N. Romashchuk writes: “This type of critique sets a particular form of transition from one theory to another, from one concept to another. But the question remains as to whether this form is relevant not only for transitions within science itself, but also for transitions between everyday and scientific theories in the learning process.”

In the present case we see that the students’ initial, shared abstract representation of the body’s boundary is first transformed into a more elaborated understanding of different types of boundaries through experiments and virtual practical work. It is then subjected to constructive critique through model-based analysis — for example, the “invention” of a multicellular body with a boundary formed by layers of cells is the result of students’ constructive critique of unicellular structure and of overcoming the size limitations inherent in unicellular organisms. In this way, the developing system of scientific knowledge formed in the students’ minds preserves earlier representations, continuing to need them as its foundation. The partial incongruence of a concept with reality, the unsettling inexhaustibility of the object that resists full comprehension — the non-conceptual dimension described by L. Radford (Radford, 2020) — may become especially tangible in the process of concretization and because of it. This is manifested in the substantive questions that arise about familiar, childhood objects.

G. G. Mikulina and O. V. Savelyeva demonstrated that the capacity for concretization is a decisive distinguishing criterion of theoretical thinking and, consequently, of fully formed knowledge (Mikulina, Savelyeva, 1997). The study conducted with the diagnostic method Sparrow and Birch revealed substantial differences in the mastery of the concept organism between the experimental and control groups. These differences concern, above all, students’ ability to use the conceptual tools they have mastered as instruments for interpreting concrete examples drawn from their prior experience — that is, to move in their understanding of organismal structure and functioning from general principles to particular cases. This allows us to speak of the development of biological thinking and of fully formed biological knowledge in these students.

Conclusion

A school subject under development should not be a direct projection of scientific knowledge into the space of instruction. If a course for schoolchildren is created as a simplified version of university-level material, most students will acquire the knowledge only formally, without understanding. Introducing the term organism by listing examples of living beings to which it applies — for instance: “A rose, a herring, a crocodile, and a mouse are living organisms” — produces an empirical generalization, a common representation, but not a concept. For a student, the word organism will mean something like: “something that exists separately and is alive, like me or my cat.” It is no coincidence that this term is often used by teachers and students as a full synonym for living being.

Developing instructional content according to the logic of ascent from the abstract to the concrete requires not only examining the history of science but, at times, constructing for educational purposes a special model—schematic representation of an “initial cell,” an initial relation that contains the potential for development into a key concept of the subject. This process is clearly visible in the example of how the representation of the body’s boundary develops into the concept of the organism.

Key disciplinary concepts formed through the ascent from the abstract to the concrete, as demonstrated in this example, become genuine supports for thinking. They serve as tools for solving a wide range of tasks and gradually transform a learner’s everyday experience. A person gains grounds for meaningful questions and substantive assertions about the objects they encounter in daily life.

1 Pasechnik, V.V., Sumatokhin, S.V., Gaponyuk, Z.G., Shvetsov, G.G. (2025). Biology. The Line of Life (Grades 5—9). Moscow: Prosveshchenie.

2 We did not find, in the history of biology, any such simple abstraction that could serve as a prototype of the initial concept for the school subject.

3 A few years ago, it was discovered that the concept of the “body boundary” in the sense mentioned above had appeared in contemporary scientific reports (Vasilov, 2020). It is possible that earlier it had not been in demand in scientific research; however, once science began to address the problems of immunity — that is, the problems of the organism’s integrity — the introduction of this concept proved to be inevitable.

4 Here and throughout, the term “respiration” is used in the sense of “cellular respiration”; however, the pupils have yet to discover the very existence of cells.

5 At this initial stage of science education, the pupils hold such a not entirely accurate understanding; they will learn about substances with ionic bonds and about electrolytic dissociation later on.

6 The fact that all molecules are in constant chaotic thermal motion has already been mastered by the pupils in a series of tasks at the previous stage.

7https://urok.1c.ru/library/biology/virtualnaya_laboratoriya_po_biologii_dykhanie_i_obmen_veshchestv_4_11_klass/tipy_granits/

8 It is clear that at this point the pupils’ notions of fat-like substances and proteins were highly abstract, but the development of these concepts follows other disciplinary trajectories and depends on how and when this material will be studied in chemistry lessons.

9 The idea of modelling with threads emerged during a discussion of the course with S. Yu. Kurganov.